Chapter 7

Data Capture and Exploitation

Abstract

In this chapter, we will discuss data at rest and data in motion, how it can be stolen, and what is at risk. We will discuss other methods of data exploitation and theft as well as cover how digital forensics can be used to reconstruct a crime scene and provide evidence. Other topics will include how to mitigate this thread specifically with encryption and how we can safeguard our data and identities. We will discuss how to set up a data capture methodology for physical and logical spying on user activities. Other topics include data capture, dissemination, and use as well as legal concerns.

Keywords

Data Capture

Exploitation

Data Theft

Digital Forensics

Data at Rest

Data in Motion

Mitigation of Risk

Encryption

Cipher

Skimmers

Identity Theft

Data Loss Prevention (DLP)

Data Leakage

Protocol Analyzer

Sniffer

Malware

Data Breach

Man in the Middle (MITM)

Eavesdropping

E-discovery

Mobile Forensics

Stochastic Forensics

Data threat

Data is everywhere. We leave digital footprints or impressions everywhere we go and by doing anything online or on a computer system, we leave our mark. Most, if not all, of this activity is traceable and can be tracked, and it is also available for data theft. We can attempt to protect ourselves or operate in a stealth manner; however, it is possible that your actions will be logged, tracked, and proven based on many factors. Digital forensic teams are called in to review systems that have been tampered with and/or when data theft has taken place, and there are many tools that can be used to prove certain activity has taken place. Lest we forget, there may also be cameras showing you were in the vicinity of a target system proving you were involved. You can remotely access these systems and it can be proven that by a source Internet protocol (IP) address, you may be involved. Even if it’s spoofed, there are other ways to track this activity.

As we see, data tracking and doing forensic work in the digital domain can prove to be helpful; however, it is not always a guarantee that data can be kept secure. As many security analysts learned in the past decade, all of the security measures in the world did not stop a perpetrator from removing classified information about the US nuclear weaponry with a thumb drive.

In this chapter, we will discuss data at rest and data in motion, how it can be stolen, and what is at risk. We will discuss other methods of data exploitation and theft as well as cover how digital forensics can be used to reconstruct a crime scene and provide evidence. Other topics will include how to mitigate this threat specifically with encryption and how we can safeguard our data and identities.

Data Theft and Surveillance

While working as a security analyst, you may be asked to investigate data loss or theft. Data loss prevention (DLP) is the activity where you or your business entity does whatever possible to safeguard from data leakage or theft. With data everywhere, safeguarding it is a considerable challenge. Data leakage, loss, or theft causes one major problem – it is no longer secure or secret.

Data theft is also a problem that is getting considerably worse. As mobile devices are stolen, data is taken on thumb drives or websites are hacked and credentials are leaked; more and more attackers are able to spy on those they target or find targets through the data they acquire. This data can have confidential information such as passwords to financial accounts, pictures of loved ones that can also become targets, and/or medical information you wish to keep secret.

Just recently, it is alleged that Apple’s iCloud has been hacked and hackers got their hands on 100’s of nude celebrity photo’s to include Kaley Cuoco, Avril Lavigne and Hayden Panettiere, Kim Kardashian, Hope Solo and Vanessa Hudgens. The claim is, although these women thought their private cloud backup was secure, it was hacked into and their private data was stolen.

Data theft can happen many ways. Physically, a pocketbook or a wallet can be stolen. Your phone or mobile device can be taken. Your laptop can be stolen. The data could be with a service provider and they could potentially become a target inadvertently making you the next target. A great example is with Target, where a security breach caused the loss of as many as 70 million customer credit cards to the hands of hackers. This is only one of many such examples; however, this one gained national attention because of the fact that many people shop at this chain of stores and use credit cards to pay for purchases.

So why is this such an issue when it comes to protecting your assets from surveillance, becoming a target and/or victim? Your data if not protected can be used against you. As an example, if your mobile device is lost or stolen and the attacker gains access, they can pose as you that is identify theft. They have access to your private information that can be used to launch a series of attacks against you and those you know.

Due diligence should be done in an effort to protect against becoming a target such as using encryption on your data so that if it is accessed, it cannot be used. Password protection allows those who gain access to a device to be challenged that may dissuade them from attempting to steal your data; however, if your password protection is not strong, it can easily be hacked. When considering surveillance, never store data that can be used against you without protecting it. It is up to you to protect against a data breach to ensure that your data is safe and secure.

Basic Data Capture Techniques

Data theft can be classified as being a physical theft or a logical theft. Physical theft is most likely to occur because it’s the easiest way to steal data. If I can steal an entire computer and access the hard disks, memory, and so on, I stand a better chance of getting the data instead of coming over the network in an elaborate hack to penetrate firewalls and other protection methods in place. Stealing print jobs off a printer is much easier than accessing a protected database logically to take data. If I can get your wallet or pocketbook and find paystubs, ATM receipts, and credit cards, I have a better chance at launching an attack then attempting to gather this information online.

Physical theft is not easy to limit if you are at risk or threatened; however, if you are not directly threatened, there are many ways to protect yourself and your data. For example, any form of physical security will limit your exposure. Something as simple as putting your wallet in your front pocket instead of your back pocket or removing items from your wallet that you do not need may help. Inventory of assets and evaluating risk are keys to mitigating the threat of physical theft. Limiting your footprint, being aware of your surroundings, doing due diligence, and assessing threats in real time can help.

Logical theft can be classified as a cyber attack. The first and most obvious way to steal data is to conduct surveillance on what is freely accessible. As we learned earlier in this book, we put a lot of information online that probably does not need to be there. Our friends and family add to it by using social media sites that increases the attacker’s ability to gather information. When entering the digital domain, there are many ways that data theft can take place, which we will discuss in depth in this chapter. Considerations to take would be how to protect data at rest or data in motion as well as physical versus logical security concerns.

Data at Rest

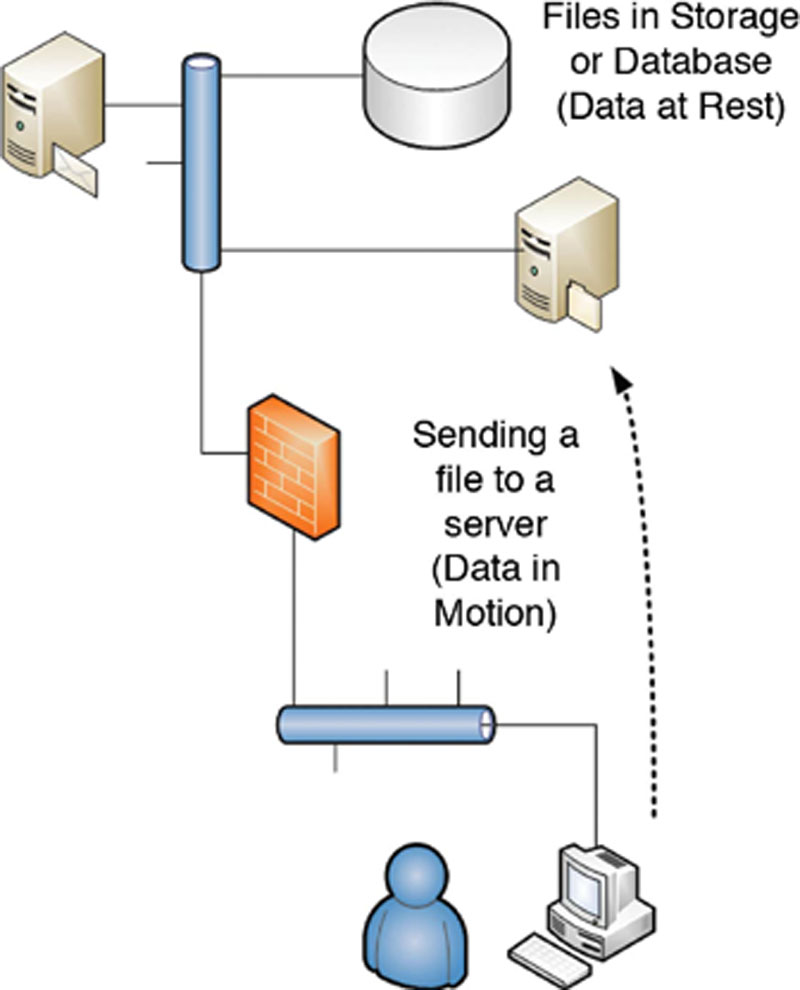

Data at rest simply means that you have data saved somewhere and it is not currently being transferred digitally from one location to another. The best way to view this is with an example. Consider you have joined a new social media website and it has asked you to set up a username and a password. Once you do, your information is saved in a database used to validate your request to login. When you attempt to login, your information is sent to the database for validation (data in motion), where it’s checked against your stored credentials in the database (data at rest). This example can be transferred to the using of file. If you create a word processor document and save it locally on your hard drive, it is data at rest. When you send that file via e-mail to a friend, it is in motion.

As seen in Figure 7.1, we can visualize how data can be stolen. Here, we can see that the computer in use can be stolen with the data on it or the server as well although it’s likely to be kept in a secure location. Data can be remotely taken from the systems via a remote attack such as a penetration. They can be stolen locally with a thumb drive.

Figure 7.1 Types of data theft.

When considering an attack where data is in motion, it’s important to understand that this will take place while the data is in transit. This means, if the data is sent from the client computer to the server, or downloaded from the server, while it is traversing the network, it can be taken. There are many forms of this type of theft that we will discuss in this chapter.

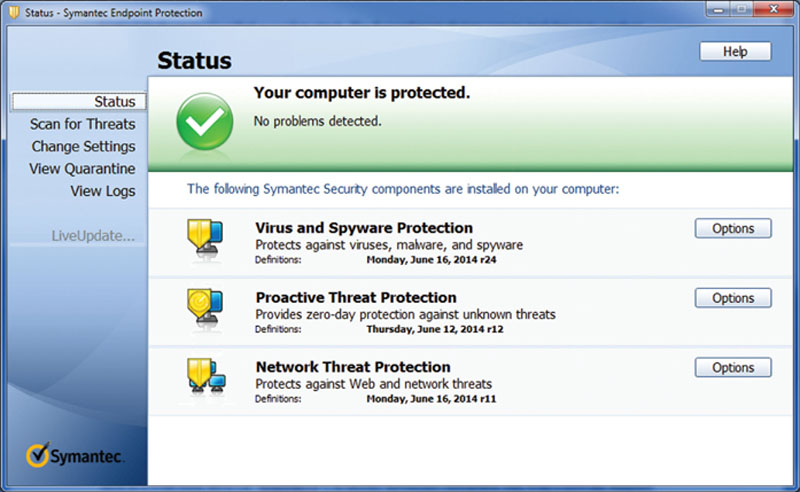

Malware Protection

Malware protection can be used to protect both data at rest and data in motion. However, it is more likely it will be protecting data at rest. When you install antivirus or anti-spyware software on your computer systems, you are attempting to protect your data from malicious attack. If a malware gets on your system, it may attempt to corrupt your data, destroy it, or allow it to be sent to an attacker. If data is infected with malware and your antivirus software is active, updated, and not corrupted itself, the software will alert you and attempt to quarantine the malware as per design.

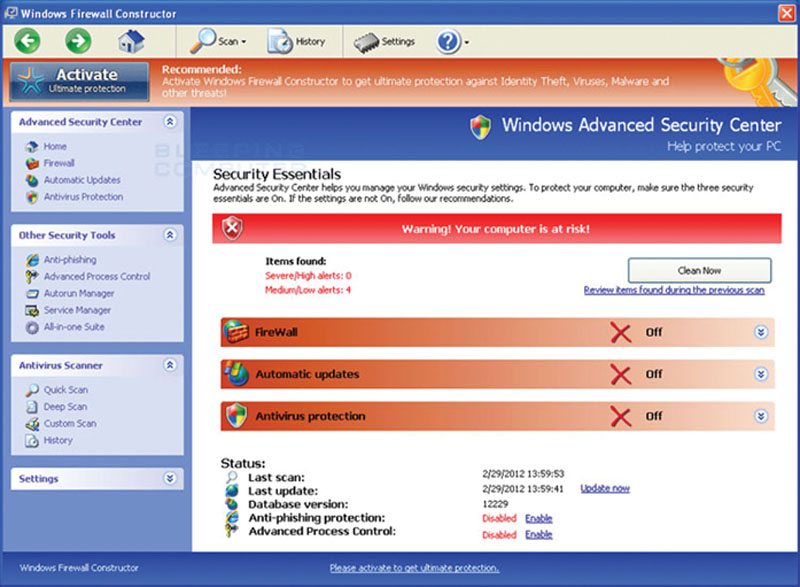

As seen in Figure 7.2, the antivirus software can protect your system (and the data) from virus and spyware threats as well as provide other safeguards such as network threat protection to protect against incoming attacks.

Figure 7.2 Typical antivirus software.

DLP Software

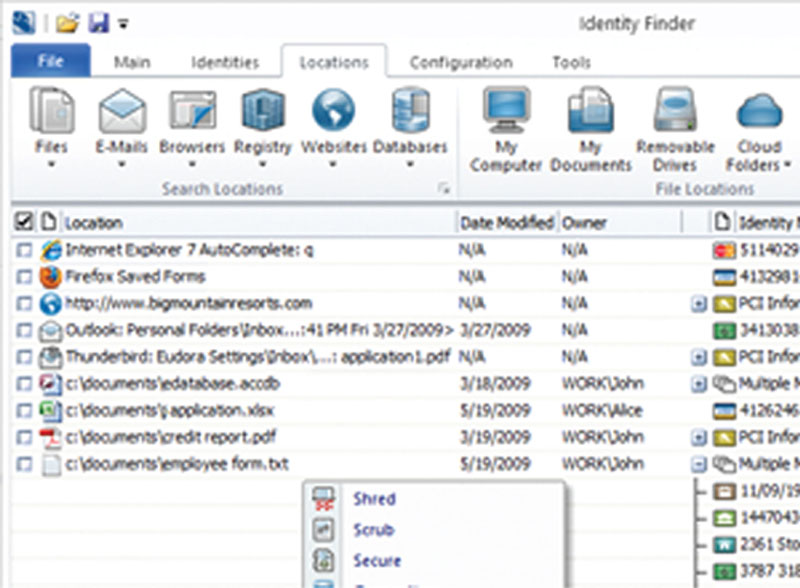

DLP software is a suite of applications that allow you to safeguard data from theft from file servers, e-mail servers, local systems, the cloud, and other locations where data is kept. It is used to consider data in motion and at rest and allows for the safeguarding of key data when used. It works by first making sure that an inventory of your data is recorded and will flag key data leaving your systems or network based on its sensitivity.

As seen in Figure 7.3, confidential sensitive data is selected to be secured and if it attempts to move beyond its policy points, it will be flagged as a violation. A good example of this is when considering health records. If sensitive patient information is added as a marker for DLP and someone attempts to e-mail patient information, DLP can be used to ensure that it is not sent thus safeguarding it.

Figure 7.3 Using identify finder for data loss prevention.

Databases, file shares, e-mail, local computers, and servers can all be configured as “endpoints.” Network DLP can be configured to safeguard sensitive data leaving your network moving from private network to public network segments. An example would be to ensure that endpoints are configured to monitor and control active threats and use network DLP at your exit (or egress) points on your network. If an attacker is able to penetrate or an internal threat such as a malicious employee decides to send sensitive data, DLP will ensure that it is kept secret.

Firewall Systems

Firewall systems are generally configured on host devices or in particular parts of a network such as ingress and egress points to ensure that malicious activity such as network and system penetration do not take place. As we discussed earlier, physical theft is easier and more likely to succeed because logical security in the form of IPS units, firewalls, and DLP software make stealing data extremely difficult to do. Since most firewalls (and other security devices) ship to the customer in a restrictive configuration making you open what you need access to, it’s likely that a misconfiguration will take place; however, they do and this is what hackers look to expose.

As seen in Figure 7.4, a typical host-based firewall (such as Microsoft Windows Firewall) can be configured to block access to a system making it difficult for an attacker to gain access to steal data.

Figure 7.4 Typical host-based firewall.

Online attacks and remote attacks are difficult because the firewall will block or restrict access and alert you to an attempt. By doing so, this prevents many attempts to penetrate the system as long as the firewall is active; it’s correctly configured and set to update you when a breach may have taken place.

Removable Media

As we have learned, remotely attacking a system has grown difficult. There was a time where you could potentially run a quick identification scan, find an open system, enter it, and have access to the data on the system. As computer system evolved, so did the many ways in which is can be secured. While we as security analysts and engineers learn of holes in our security design, we make attempts to close them with tools, software, and other methods. As we close them, attackers learn of new ways to penetrate systems around the protection methods put in place. One of the key ways data theft grew based on the period of time where firewalls and other security tools were put in place was by stealing the data locally directly from the system. For example, removable media such as DVD-ROMS, external and thumb drives, and other forms of media were used to access a system locally, dump the data directly on to them, and then walk away without being caught. Note that if there are cameras or other forms of security in place, you will still be seen touching the system; however, not all systems are protected with video surveillance.

Thumb drives are the most common because they fit in your pocket avoiding detection and allowing you to quietly and covertly take data from a system without anyone’s knowledge. One of the best examples of a major data theft that was brought to the attention of national news headlines was in Los Alamos when a US nuclear-based vault was penetrated and a USB thumb drive (flash drive) was used to remove classified documentation about nuclear weapons. What should a common computer user worry about? This same attack can be used against you to gather your important data. A friend or relative can conduct the same exact attack at your home. They can access your system during Christmas dinner by downloading all of your important documents and data in seconds.

As seen in Figure 7.5, removable media can be attached to your computer system and data can be taken without your knowledge. In this example, a simple flash drive was inserted in an open USB slot that allowed the drive to be populated with data and was quickly removed and taken with the attacker.

Figure 7.5 Removable media threat.

Removable media attacks are a convenient way for an attacker to quickly access and remove your data from your machine. We see this being done in movies all of the time. This type of attack is called thumbsucking. What makes this attack so concerning is that as devices evolved, their capacity has also increased exponentially that gives the attacker the ability to potentially take all of the data on your drive without being caught.

Encryption Protection

With the concerns of removable media attacks, data in motion, and data theft, in general, a method to protect against each form was invoked to ensure that if data was in fact stolen, it would be unusable to those who may have gathered it. Encryption is the process of applying a cipher to make data unreadable to those without the ability to decrypt it. Encryption can be applied to data at rest and in motion. It should be noted that encryption protection can in fact be thwarted. There are tools out there that can be used to break encryption to decipher and gain access to your protected data. Thus being said, make sure that you use a “strong” encryption method allowing for data to be secure if stolen.

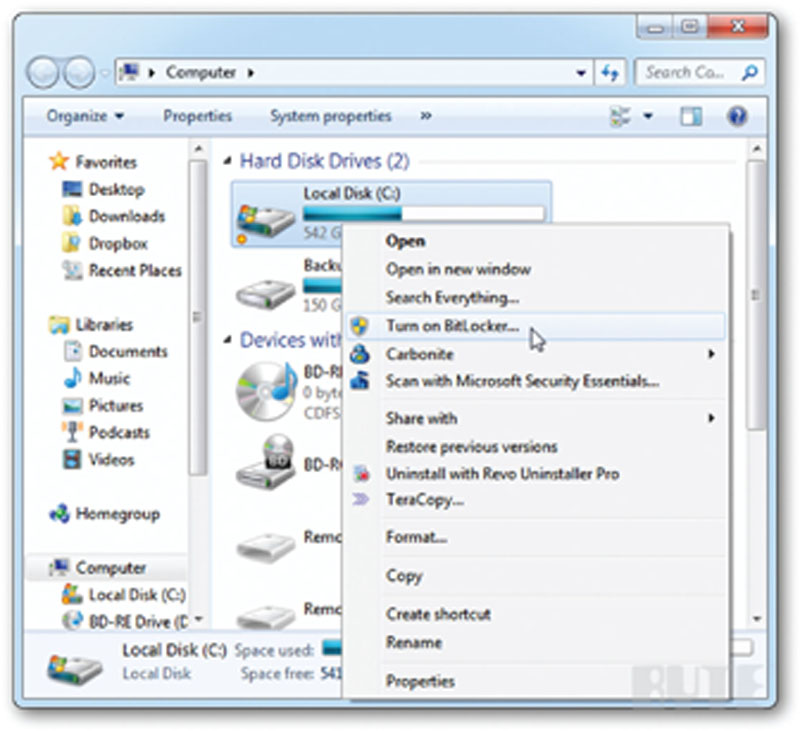

As seen in Figure 7.6, encryption through a software tool can apply encryption to folders of data, to drives, and even protect access against USB drives where if used for malicious purposes will only allow those who may have stolen data to read it if they have the key or passphrase.

Figure 7.6 Applying encryption to your system.

Other methods such as encrypting an entire disk drive is recommended for those who want to ensure that if their system is stolen, the data cannot be accessed without unlocking it first. This is very handy for those who want to safeguard their mobile systems such as laptops.

Windows BitLocker drive encryption is a Microsoft-based encryption method where data protection can be applied through encrypting all of the data stored on your drive. It will encrypt volumes on your drive (the logical location where your data is stored) such as Drive C. As seen in Figure 7.7, if you apply BitLocker on your local drive, you can protect the data if the device is stolen.

Figure 7.7 Using Windows BitLocker encryption.

To use this technology, it should be noted that specialized hardware can be used to store encryption keys. This technology is called the trusted platform module (TPM) and is a microchip found on the local computer or can be used with a USB drive to store the keys. Obviously, if the attacker gains access to the keys, the encryption can be decrypted giving access to your data.

It should be noted that encryption if strong and keys if secured can protect your data from being stolen or locally tampered. However, what about sending data such as a secure e-mail to another recipient? Can it also be secured?

This is a good segue into discussions on data in motion because encryption can be applied in the same fashion, which will protect data in motion.

Data in Motion

Capturing data in transit can be done in many ways. If you are viewing it from a source to destination framework where you are sending files via an FTP program, or sending an e-mail, there are many ways in which an attacker can gain access to your secured data. As the data leaves your client system and traverses the network (wired or wireless), it can be captured in transit. One of the most common ways is using a network data capture device. We will learn in this section just how easily a capture can be set up so that as data is sent, it can be “sniffed” or captured and analyzed to disclose information such as credentials to website logins and much more. You can also spoof a website as an example and capture data such as credentials as it flows from source to destination. This way, a victim will send data from source to destination and it can be captured in transit by a collection device.

You can also skim data from a credit or a debit card through a hardware device as it sits as a shim in between the card and the actual reader. Attackers are getting good at stealing data and one of the key ways they are able to steal financial data is with card skimmers.

DLP software can protect egress points as well as firewalls; however, they cannot capture anything. Lower exposure by educating yourself and others on what should be sent and how it would limit risk; however, DLP can be used to capture and analyze data in motion that goes against security policies in place.

There are also ways that data can be secured in transit. Endpoints can be encrypted from point to point, such as via VPN tunnel that can prevent eavesdropping attacks from taking place. Mail can be sent with encryption and can be decrypted by the recipient. Although most of these tasks require effort, they can help prevent exposure and data theft.

Sniffers

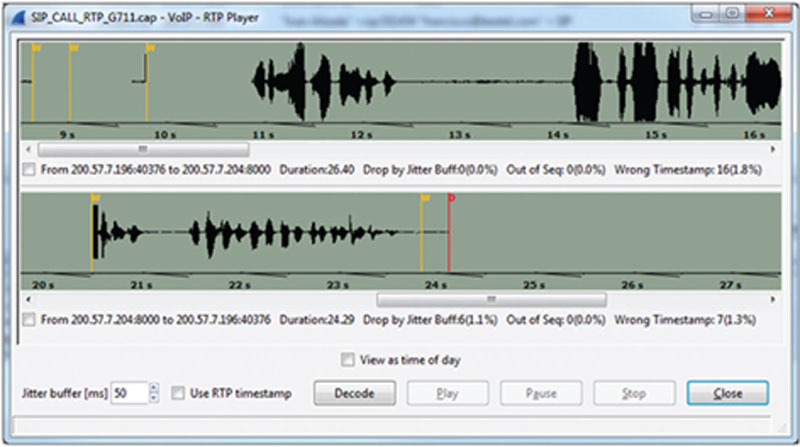

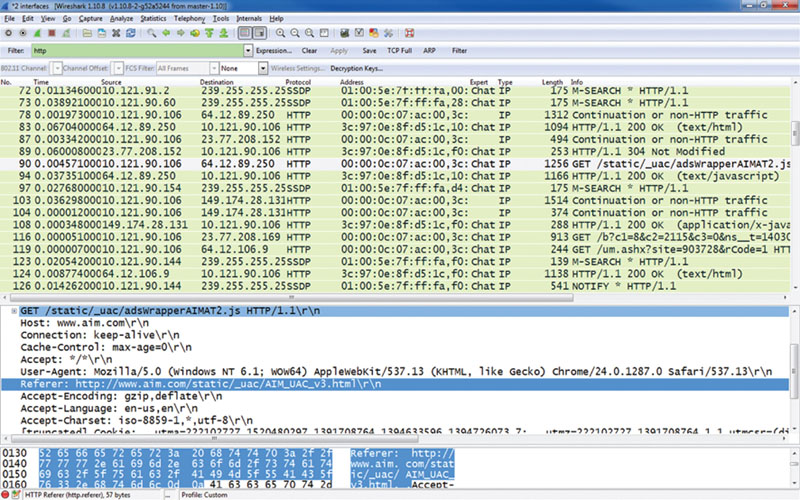

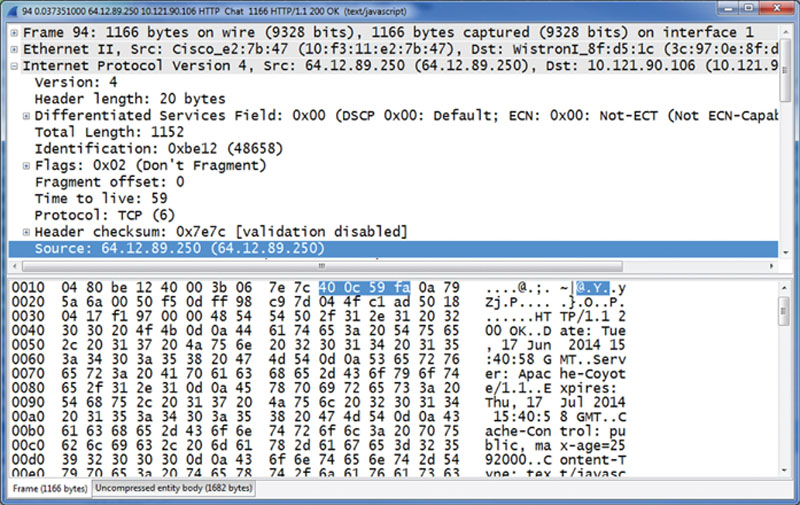

A protocol analyzer (also known as a sniffer, packet analyzer, network analyzer, or traffic analyzer) can capture data in transit for the purpose of analysis and review. Sniffers allow an attacker to inject themselves between a conversation between a digital source and destination in hopes of capturing useful data. Some data if unencrypted can be opened and viewed. Credentials can be sent in cleartext exposing your secured logins to risk. As seen in Figure 7.8, unless encrypted in a way that cannot be decrypted easily, any and all data sent to and from can be viewed and used for wrongdoing.

Figure 7.8 Using a sniffer to capture data.

Sniffers are used for good reasons and mostly to troubleshoot problems on networks and systems. It is when they are used for the wrong reason that threats can take place, for example, if an attacker was able to set up a sniffer to capture the traffic you send and is able to capture unencrypted e-mail, passwords to websites, and so on, in order to use this data against you. As you can see, this data can be deciphered to show you source IP addresses as well, which may show the attacker where they need to focus a penetration attack. As seen in Figure 7.9, an attacker could capture a source IP address (which is where you may be originating from) in order to launch a logical attack to gather data, conduct other reconnaissance missions, or penetrate to gain data access.

Figure 7.9 Finding a source IP address.

If this can only be protected against with encryption, how can you thwart these attacks? For one, a sniffer needs to be loaded on a machine for it to be used. There are cases where it can be loaded elsewhere and have data sent to it; however, most times the capture will be directly conducted on the source system. Again, you have to be conscious of what is loaded on your systems in order to make sure it’s not loading and collecting data. This was the same practice we implemented when we discussed mobile phones and knowing what is loaded on it in order to protect against malware.

Skimmers

As ATM cash machines and other card swipe systems grow to expand financial institutions reach, make cash ready and easy to access, and allow ease of use for consumers to use credit cards, more and more attackers are deploying card skimmers to capture your credit or debit card information as you enter it into a legitimate machine to access your banking information.

Data skimmers, generally used to obtain financial gain, make duplicate cards or sell your information to others for identity theft exploitation. Data exploitation causes those who pull off these attacks to experience financial gain and access to your data. This form of data theft can occur anywhere worldwide, anywhere an ATM or a card swipe technology is available.

What makes this attack incredibly frustrating to those who are victimized is that it is so hard to detect. Most times, attackers are able to put a skimmer on a legitimate ATM machine and unbeknownst to those who use it, it collects the data from the card without the victim’s knowledge. As seen in Figure 7.11, card skimmers can be installed quickly and easily as they cover the face of the real card reader allowing the attacker to collect this data while you are able to still conduct your original transaction.

Figure 7.11 Data theft via card skimmer.

Once the card information is collected, it can be used as it will collect all information on the card including the track information. Once this is collected, the card can be duplicated and used. To mitigate this threat, attempt to only use ATM systems and other card swipe technology that is under video surveillance, which will limit an attacker’s ability to install a skimmer. Generally, those who are able to view a skimmer by eye will see that at times it protrudes from the original reader slightly; however, you may not always be able to see them. If you feel that your card information has been stolen, immediately call your financial institution. Today, most financial institutions track fraud in real time and will shut down your card before you are even aware that it’s been used in a fraudulent way.

Digital Forensics

Once data has been stolen, it may wind up in the court of law as evidence if in fact a crime has been committed and the evidence is recoverable. This is where forensics becomes incredibly important. Digital forensics is the process of investigating data theft so that it can be analyzed for artifacts, proof, evidence and possibly to reconstruct a crime scene. We explain this here because although it may be outside of the realm of data theft from an attacker where you may be the victim, it is important to consider that if caught, the attacker may face criminal charges. Data theft of your financial information that causes a crime to take place can be found in the devices of those who conducted the crime and if this evidence is captured, could be used against the attacker.

What is also important to consider is, from a surveillance point of view, any data even data you think you may have erased could possibly be resurrected with digital forensic tools and software. As an example, if you are using a mobile device and a crime has been committed, it’s recommended to plug the phone in and keep it powered on until it can be investigated so that everything that remains in memory can be captured whereas if you power it off, data may be lost. It is also important to consider that where you believe that by securing your data, that does not mean that a government agency such as the FBI or NSA cannot recover it.

Devices and Applications

There are many devices and applications that can be used to capture data on a system or in memory in order to perform forensic work. Once of the most common applications in use today is Encase. This software created by Guidance Software is one of the de facto standards used to do digital forensics and e-discovery to reconstruct crime scenes. This tool can be used on computer systems, servers, mobile devices, and more. As seen in Figure 7.12, performing forensic work can also take place with hardware devices that can be plugged into and used to capture data from devices such as a mobile phone. In this example, a UFED device from Cellebrite is used to capture mobile data.

Figure 7.12 Mobile device forensics.

Mobile forensics will allow an analyst to view call logs, text logs, data on the phone, in memory, and much more. There are other devices as well such as a Tableau analyzer as seen in Figure 7.13, which allows data to be captured and advanced analytics to be performed. Although this focuses on business intelligence analytics, data is still being captured, read from a device, and used to reconstruct evidence.

Figure 7.13 Advanced data capture and analysis.

In sum, it should be noted that digital forensics is done for the purpose of good, to reconstruct a crime and provide evidence. As we have learned throughout this book, that does not mean these devices will always be used by those with good intentions. It also does not mean that those entrusted with using them will not alter the data they find or delete it completely.

This is what is so concerning about these tools and how most if not much of what we do resides in the digital domain. Your data is not secure; there is a way to get it either from attackers or working professionals. As we move into our last chapter, we will solely focus on how to mitigate most if not all of the risks brought to light in this book in hopes that by now you understand that you need to consider the risks of using anything digitally. That mobile devices are a threat if stolen, you can be tracked … you can be spied on easily.

Legal and ethical concerns

In this section, we will discuss another case where legal issues and concerns were brought to light. In this murder charge where cybercrime was involved, data exploitation and other tactics were involved by the attacker.

In early 2000, Defendant Michelle Catherine Theer met United States Army Sergeant John Diamond, a Special Forces soldier stationed in Fayetteville at Fort Bragg, via the Internet and began an extramarital affair with him. Months later Sergeant Diamond sent e-mails to Theer indicating he was unhappy about the possibility of their relationship ending and her remaining with her husband.

At sentencing in December 2004, a jury trial found Theer guilty of first-degree murder by aiding and abetting, and of conspiracy to commit first-degree murder in the death of her husband, United States Air Force Captain Frank Martin Theer.

Some of the evidence used to convict her consisted of documents and computer records. The jury was also presented with evidence as to Theer’s Internet posting and alternative lifestyle for the limited purpose of evaluating of the marital status of the defendant and her husband, as well as Theer’s mental status, Theer argues that this testimony about the computer documents and e-mails should have been excluded as bad character evidence, as it made her out to be a “moral degenerate’ and went beyond simply chronicling her extramarital affairs.

Summary

Data is everywhere. We leave digital footprints or impressions everywhere we go and by doing anything online or on a computer system, we leave our mark. Most, if not all, of this activity is traceable and can be tracked, and it is also available for data theft. We can attempt to protect ourselves or operate in a stealth manner; however, it is possible that your actions will be logged, tracked, and proven based on many factors. Digital forensic teams are called in to review systems that have been tampered with and/or when data theft has taken place and there are many tools that can be used to prove certain activity has taken place. Lest we forget, there may also be cameras showing you were in the vicinity of a target system proving you were involved. You can remotely access these systems and it can be proven that by a source IP address, you may be involved. Even if it’s spoofed, there are other ways to track this activity.

As we see, data tracking and doing forensic work in the digital domain can prove to be helpful; however, it is not always a guarantee that data can be kept secure. As many security analysts learned in the past decade, all of the security measures in the world did not stop a perpetrator from removing classified information about US nuclear weaponry with a thumb drive.

In this chapter, we discussed data at rest and data in motion and discussed how it can be stolen and what is at risk. We also covered the methods of data exploitation and theft as well as how digital forensics can be used to reconstruct a crime scene and provide evidence. Other topics covered include how to mitigate this thread specifically with encryption and how we can safeguard our data and identities.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.