Chapter 2

Information Gathering

Abstract

In this chapter, we learn about why information gathering physically and logically is so relevant to spying, reconnaissance, and surveillance. Why a majority of spying is easily conducted over the public Internet. We discuss social media topics, National Security Agency topics (Snowden), how to conduct information gathering using simply found tools, and how to start spying on a user, group, or entity. We also discuss how to mitigate and the legal and ethical concerns that are raised.

Keywords

Backtrack

Wiretapping

Facebook

Digital Footprint

Social Media

Information Gathering

Mitigate

Identity Theft

Infiltration

Invasion of Privacy

Packet Analysis

Internet

Twitter

Wireless Networking

Maltego

Information gathering

When conducting digital surveillance and reconnaissance, one of the priorities of these tasks is to gather information on a target or a group of targets. No simple task, however, within the digital world, it makes it much easier to do and it can be done from afar. If you know how to cover your tracks, it can also be done privately without concern of being discovered. Prior to using technology, to gather information you would need to physically be on location and hope to not be seen or get caught. As technology became more available, it could then be tapped to reveal information about targets. For example, a phone could be “bugged” with a device to listen to a conversation and recorded. This technique was used to leverage the weaknesses in the old publically switched telephone network that operated with analog technology. Now, with the progress made in the digital realm, you can be at a computer terminal or on your mobile device anywhere in the world, connect to the public Internet, and gather a large amount of information on a variety of targets within minutes all while remaining undetected. This chapter covers many of the methods in which this can be done.

Why is this so important? For one, to be able to attack, you need to find vectors in which you can breech your target. The old analog phone example is a good one to understand the increasing attack vector. Now with digital technology, your telephone conversation can be stored digital within a private branch exchange device, locally to the phone or captured in transmission. Applications can be placed on the receiver device to capture or listen to the conversation. There are more points in the transmission to capture data and more locations in which it is stored.

Now that you are aware of the fact that information can be gathered and it can be quickly and easily acquired, we should consider all of the points in which it can be collected. As well, is all information gathering malicious? Once you understand the attack vector, you can consider if your information is truly private and you can learn to protect yourself and mitigate attack.

Am I Being Spied On?

The first question to ask is, “am I being spied on?” This is a question that just invites paranoia into the minds of many. However, it is a good question to ask because by doing so, it makes you think about protecting yourself, your data, and your interests. It also gets you to consider your digital footprint, that is, where you leave your mark in the digital world. For example, sending a simple e-mail from work to another recipient. Consider that the recipient is also at work. If you are concerned about your information being private, you do not need to look any further than your organizations security policy and specifically on e-mail usage and retention. The fact is, if your policy states that the data you send and receive is by default owned by the organization when using their systems, then the answer is no. Your communications are not private. Now, let’s consider that you are under investigation by Human Resources for a workplace matter. If an issue, complaint, or security violation is suspected, your e-mail can be reviewed by appropriate parties. Something as harmless as showing interest in co-workers and asking them out for a drink could easily turn into a sexual harassment case.

Now let’s consider if you send a private communication from your personal e-mail account to another recipient. Is your communication truly private? The answer is no. Quite simply, if you’re under investigation, your data can be subpoenaed by the judge for forensic review within the court. The Internet Service Provider (ISP) who holds your e-mail account would need to comply.

Another consideration is what if I wasn’t at work and I wasn’t involved in a legal case? Is my transmission private? It could be, however, according to data released on the National Security Agency, data transmissions are captured and filtered. This simple example of an e-mail transmission continues on if you consider that your device could be stolen. You could be hacked or it’s possible someone or something has tampered with your system and collecting your data.

The answer to the question, “Am I being spied on?” is not easily provided. The answer could be your data is never truly private and could be collected at any time for just about any reason, legally or maliciously. If maliciously, you may or may not know your privacy is being violated. Attackers wish to remain anonymous, so they usually conduct surveillance activities with the intentions of remaining anonymous and/or going undetected. Also, governments collecting information on their citizens generally do not want to advertise such activity.

How Private Is Your Life?

As we learned in Chapter 1, everything you do within the digital domain can potentially be stored to include video footage of you going to a local store, when you use your mobile phone and it connects to a cell tower, when you access your favorite social media site, or if you log in to your bank to pay a bill.

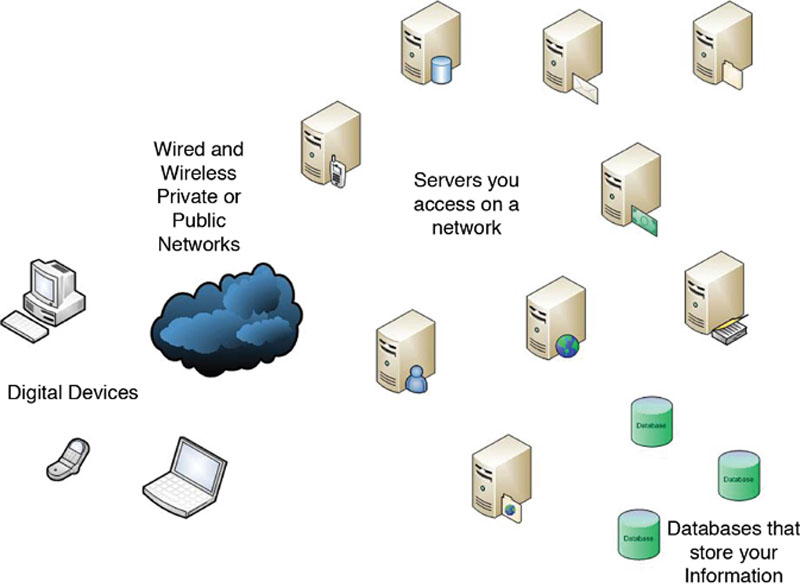

In Figure 2.1, we provide an extremely high-level view of the digital landscape and all of the points within it that data is or can be stored. Every one of these points can also be used for information gathering.

Figure 2.1 Information gathering points.

In this example, we see digital devices such as a laptop or a phone accessing a network to use a resource. These resources can include going to a website to purchase goods, to send an e-mail, to upload a file, or to text with a friend. Every transmission from source to destination leaves residual evidence of the transaction in logs if configured. Data and transmissions are time stamped and a digital forensics expert can uncover a complete map of activity.

As seen in the figure, you can use any device to connect through any network to any resource and your activity can be captured. Marketing firms work very hard to conduct tracking activities to know how to track your buying habits in an effort to show you only the items you may be interested in or have an impulse to buy. This does not necessarily mean that someone or an entity is spying on you in a way that seems to imply that you are in danger; however, it does open your mind to the fact that your habits are tracked and if this data was to get into the wrong hands, could be used against you. For example, within social media sites such as Facebook, by simply “liking” a post, it is added to Facebook internal databases and if what you like is something that may be deemed offensive to some, could impact your privacy since it can be freely searched by others.

This is where surveillance activities can also tie in. If someone was looking to gather information about you in hopes to conduct an attack such as identity theft or password cracking of your protected data, understanding what you like gives attackers a foothold on being able to conduct these types of attacks.

Another problem with data stored on systems is that it could come back to haunt you. For example, if 10 years ago you were involved in criminal behavior but have had your charges expunged, it will not matter when that data is found by prospective job search recruiters looking for viable candidates for an open position. This is a simple example of the many ways that data can be mined in hopes to conduct an attack.

Examples of Privacy Invasion

There are many other examples of how privacy is no longer a guarantee. Consider a typical user of digital technology living in the world today. You leave your home in the morning and go to work. You go out for a lunch date and run an errand. You return to work and once the day is over, go back home. If you are using digital technology in the form of a mobile device and took it with you during these events, there could be a traceable footprint of where you went and at what time. You are under constant video surveillance just about anywhere you go, recording everything you do. Every location you went to likely had a video camera within or in the path to each destination. You paid by credit card when you had lunch. You placed seven phone calls on your mobile phone that day and sent 22 text messages. While at work, you made 19 phone calls and sent and received 120 e-mails.

As you can see, we can continue to flesh out this example by looking at what applications were used on the mobile device, and what systems and servers were used while at work or any other examples of digital technology used within this specific time span; however, it should be enough to show you that your life is under surveillance and all of your actions are digitally recorded or traceable.

Outside of the digital world, it’s possible that you could be watched by those with an interest in watching what you do. If you are the subject of someone under investigation you could be videotaped or photographed. If someone is stalking you, they could potentially follow you to see where you go, who you are with, and what you are doing.

In the physical and digital worlds, your privacy could be at risk and you could be the subject of damages by those who wish to do you harm. Harm can come in many forms. It may not be physical harm but what if while at the restaurant having lunch your credit card information was stolen? What if somehow your credit was damaged or if you used a debit card your bank account emptied? As you can see, invasion to your privacy could at any moment directly impact you at any time.

To protect yourself from being spied on you need to limit your exposure. By living in a digital world where you use your mobile phone and post pictures and engage in social media websites, you need to understand by doing so you subject yourself to exposure. Even if you attempt to mitigate attack by limiting exposure within each technology you use, you have to consider that you may miss something and/or someone you trust may expose you. You could use a credit card instead of a debit card or you could pay in cash. You could turn off your mobile phone if you did not wish to be tracked via cell towers. You could choose not to send an e-mail.

Also, we have focused on individuals; however, entities and groups could also be at risk. For example, let’s assume that an attacker wants to spy on a company. They could gather information publically online using many sources such as a Who is database to pull Domain Name System (DNS) information that could potentially show personal information. They could use the Better Business Bureau website to gather information on a business track record.

All in all, it should be noted that maintaining privacy comes down to minimizing exposure and being aware of your activities. To exist in a digital world, it may be difficult to conceal your actions.

How to Gather Information

Gathering information can be quickly and easily done. Now that you understand your footprint, let’s take a look at some of the ways your privacy can be evaded. There are many surveillance tools as well as those that do specific information gathering tasks and others that are manual tools where information can be collected and correlated.

In this section, we look at specific tools that can be used to conduct these tasks. Before we do we should generalize their use and impact and the reasons why they are so popular in the first place.

Data mining of information is not a new practice. As more and more data is centralized and tools evolve to do a better job of extracting key information for reporting and general use, the ability to use this for spying grows exponentially. Big data and informatics/analytics are major areas of technology growth today, where organizations need to tap their stored data to derive specific results from it. When considering how this type of data analysis can be used or misused, it’s safe to say that regardless, the data is gathered, stored, and, if exploited, could be used against a target.

Information Gathering Tools

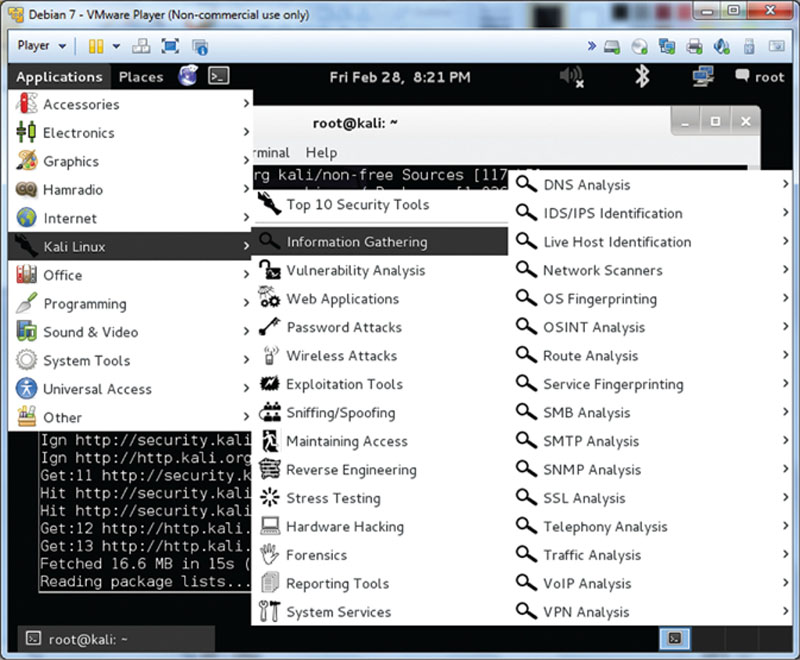

One of the most interesting tools to assist security professionals to come to light is called Backtrack. Backtrack is used to provide penetration testing analysts, a portfolio of security tools that can be used to test the security of a system, network, or service. If placed in the wrong hands, it can, in fact, be used to conduct surveillance of targets.

As an example, I have loaded Backtrack within Kali Linux as a virtual machine to demonstrate the product as seen in Figure 2.3. Once loaded, you can click on Applications and follow the path in the graphic to Information Gathering where you will find many tools that you can use that will collect, gather, and exploit data from a source.

Figure 2.3 Using Backtrack.

Some of the tools within Backtrack such as Creepy will allow you to target Twitter accounts as well as Flickr accounts via Yahoo. We will get into more detail on how picture metadata can be used to exploit a target; however, for now, load up the tools and review what is offered within the toolset. Another interesting point to mention about Backtrack is how it uses network-level protocols such as DNS, Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP), and Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) to gather information from a target.

Backtrack is commonly used by Penetration Testers and Security Analysts to conduct security review of software, systems, services, and infrastructure to produce a report on where weaknesses exist and adjustments need to be made. In the wrong hands, it can be used to gather information on unsuspecting targets.

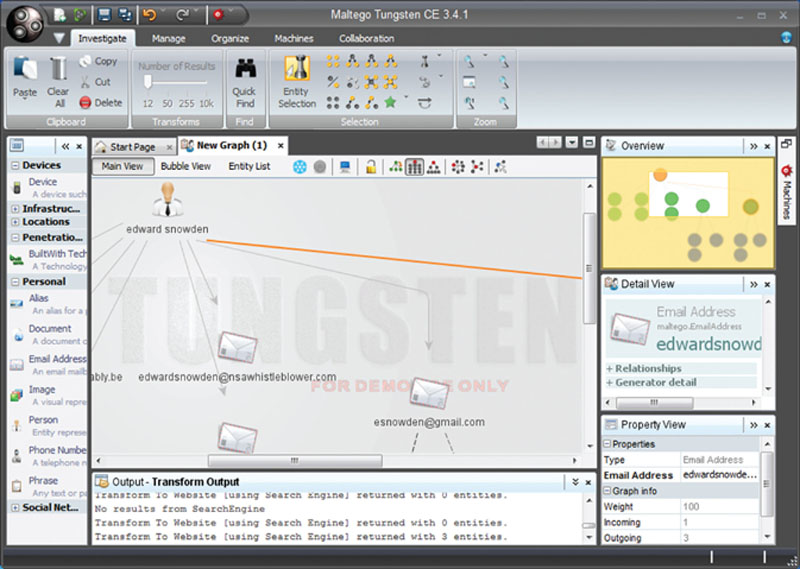

You can also build databases of information to conduct investigations on targets. A tool such as Maltego Tungsten can be populated with a subject or set of subjects as seen in Figure 2.4. Once populated, you can run queries against the source data and gather information on a target. In this example, I used Edward Snowden and attempted to map known e-mail accounts.

Figure 2.4 Using Maltego.

Data mining can then be performed to gather more information and a “case file” can be created for future use or reference. This tool in the wrong hands can become a stalkers dream. Imagine an ex-boyfriend or girlfriend having the power to create a file on you and keep it updated to track any known information about you. These are tools custom built to assist with data information gathering and are very good at it.

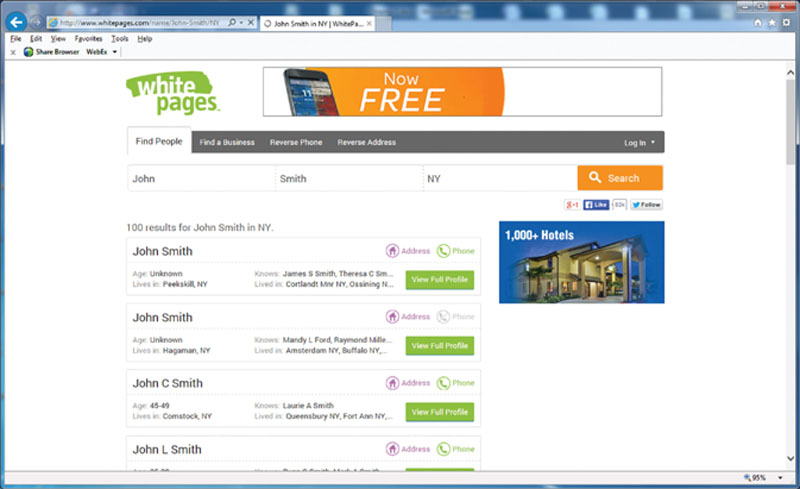

You can also tap into already established and legitimate tools to gather data. For example, if you are able to go online and use a search engine, you can conduct a large amount of data collection by understanding key words and how to search using an engine. For example, if you knew a target by name, you can then begin to add information after the name to include key words such as “addresses,” “phone number,” and so on. There are literally hundreds of databases online that contain personal information that are freely searchable. A notable one could be the White Pages seen in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 Searching online databases.

As we can see, you can also find address information and other personal information about a target without downloading and installing any tools. One point to mention is, as I used “John Smith” in my search, the more generic the name, the harder it is to search for their private information.

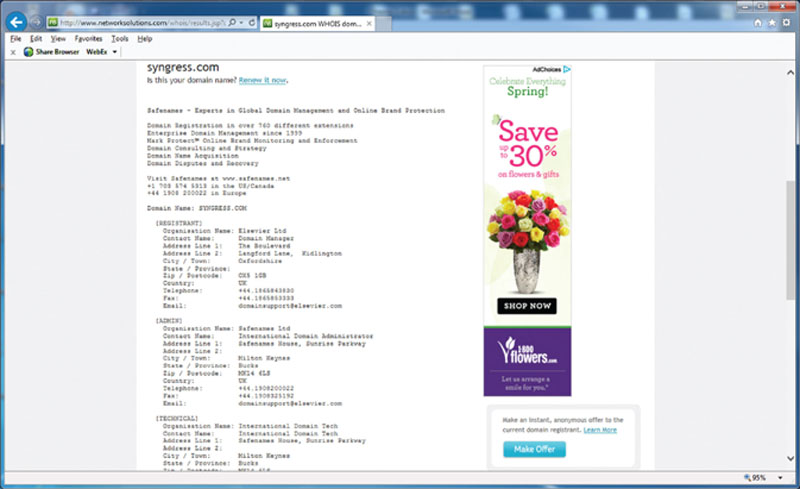

There are information gathering techniques that can also be used against an organization if that was your intended target. For example, here you can run a query against a domain name in a Who is database and find out contact information as well as location. By gathering this data, you could conduct a social engineering attack to gather more information. As seen in Figure 2.6, gathering data on a corporate entity to conduct an attack such as a social engineering attack could be done quickly using the Internet and a Who is database search.

Figure 2.6 Conducting a Whois search.

As you can see, gathering information can be easily and quickly done and if you are organized and have a few pieces of key information to start with such as a name or a location of a target, you can map out information that can be used to conduct surveillance, such as the location of the target as an example.

Other paths can be used as we will see in the next section as we expand on information gathering; however, before we do, we must understand the legal and ethical concerns that are raised when performing such actions.

Online reconnaissance

As we learned in the last section, there is a lot of information you can gather on a target using the public Internet. Our focus in this part of this chapter is to show you just how easily it can be done. Online reconnaissance takes place when an attacker consciously decides to spy and conduct surveillance on a target using the Internet as their method of doing so. They do so with the intention of gathering intelligence and data on their target to plan an attack of some kind. The attacks are many; however, you can consider stalking being one of the most common. In this section of this chapter, we will look at the infrastructure that delivers the Internet as well as the applications, sites, pages, and other media that is used within it acting as resources and services. We will also take a look at the attacks that are performed and ways to mitigate them or lower your exposure to being attacked.

The Internet Threat

The public Internet is a goldmine for those conducting intelligence. When used in non-malicious ways, the Internet can be a source of a lot of information. Research on a homework assignment, locating the best travel path, or getting movie times are all simple examples of what can be done in seconds without having to leave your home or pick up your phone. When used for good reasons, the Internet can prove to be extremely helpful; however, when used for bad reasons, the Internet can be used to gather information to conduct attacks.

Another issue with the Internet is that once you put something on a server such as a blog post, a data file, or other source of data, it could remain there for a long time, possibly forever. Data backups collect data from servers and archive it.

Data can also be added without your knowledge. In the world of social media, it’s common for people you connect to and with to “post” data such as an old picture of you. It can also be done in real time. For example, a favorite bar you frequently visit can quickly be online news if someone posts about it, tags a picture of you within it, or they post that you are in a group at a certain location. Attackers can use this information to ascertain your habits, favorite frequented places, and many other facts about you.

Data can also be doctored. Pictures can be digitally edited, words can be manipulated, and if someone has stolen your identity and posing (and posting) as you on the Internet, could cause serious issues for you.

Information is also added willingly, almost too willingly by many. Social media sites today encourage those who are part of them to post data, connect to others for no other reason other than to increase their numbers, and like things you normally wouldn’t ever comment on outside of the digital world.

So, in sum, without any effort at all, your information can be added to the publically searchable Internet within seconds, stay within it indefinitely, and even if you think you have had it removed, it could still be archived somewhere for retrieval.

To add, this does not include the data that can be obtained from globally interconnected devices that can also provide those who seek information a source to get it. Servers cache data as an example to speed up Internet browsing and if this system was hacked, could reveal the browsing habits of an entire community as an example.

We should be concerned as a society, that if those who wish to do us harm need only to first have an Internet connection and second a “will” to be interested in gathering data on you, that all it takes is a few clicks of their mouse to obtain it.

Search Engines

Search Engines provide a wealth of information to those who know how to use it. As we just discussed, there is a public Internet full of information that is gathered en masse. Key word searches and refinement of topics as well as using specific tools and websites can give an attacker anything they need to begin surveillance on a target. As an example seen in Figure 2.7, you can search for anything within a search engine and it will attempt to show you data on your search query.

Figure 2.7 Searching for data with Google.

In this example, the search for Edward Snowden pulled up interesting articles, pictures (images), and many other pieces of information. This can also be refined by altering your key word search to include information such as “address,” “phone number,” or “contact” to narrow down what has been posted or placed on the Internet and as you search through the findings, you may just find it.

It should be noted that not all information found on the Internet is either relevant or factual. Just remember that if it is posted, it exists therefore you should not consider that all information you find is real. It just means it was tagged a certain way to be picked up by the search engines and based on “relevancy” will raise the most relevant to the top of the search findings.

Phishing

Phishing is an attack where an attacker is able to pose as a legitimate source on the Internet to trick you into believing they are the legitimate entities you are attempting to visit. When searching the Internet, you may find (or go directly to) a website where you want to conduct business. For example, let’s use the example of logging into your bank account online to conduct a transaction.

If an attacker is able to manipulate that site either through manipulating DNS or through redirecting your browser, you would be brought to a site that you thought may be real, which in fact may be a phishing site. When you attach to it, you may put in your credentials and find out quickly that it is not in fact the site you wished to visit. That being said, the attacker has gathered information on you to be used to defraud you, steal from you, or conduct other attacks. If you use the same username and password for all of your sites, you have just given access to every site you have protected.

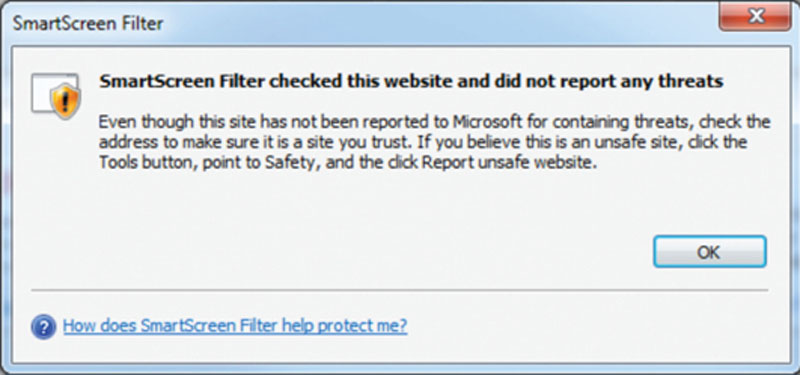

Protection against this attack can be found in most modern web browsers on the market today. Internet Explorer, for example, has a SmartScreen filter that runs a check against an online database to verify if a site is authentic as seen in Figure 2.8.

Figure 2.8 Content filtering.

Tracking

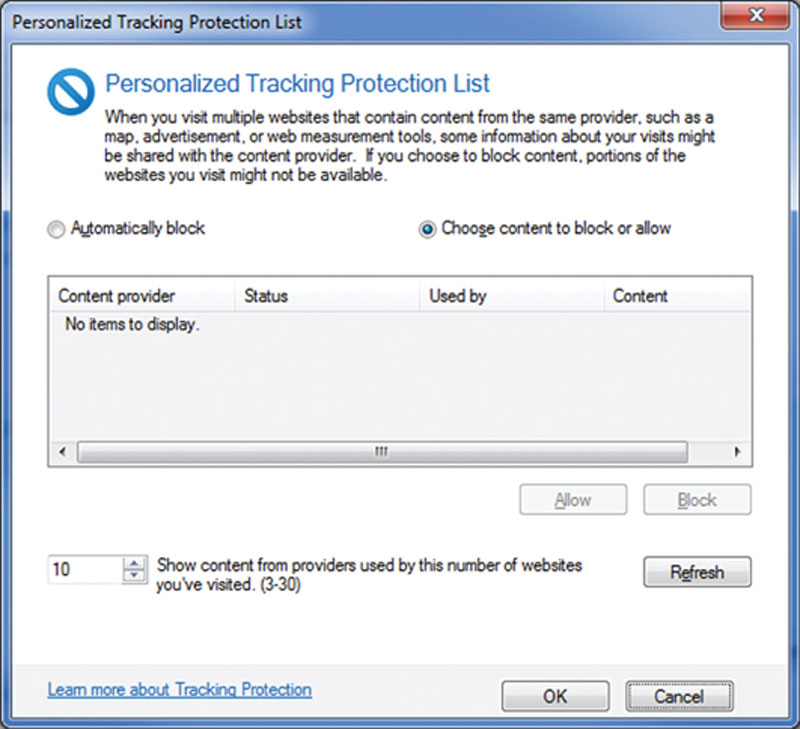

Another way you can be subject to information gathering is by websites that track who you are and where you come from. This can be used for marketing purposes; however, in the hands of those who wish to do harm, can be used to track you interests, location, your digital device (such as your PC), and your identity.

There are tools that allow you to block content, stop cookie usage, and other methods to stop personalized tracking of your digital footprint. You can use the Internet Explorer Tracking Protection options as seen in Figure 2.9 to ensure that you control what information is leaked out about you.

Figure 2.9 Microsoft tracking protection list.

Social Media

Social media sites are popping up in droves and all of them offer a way to connect and share. It’s a way to socialize with long lost friends, family, or your co-workers. You can conduct business, share data, and meet new people, find new opportunities, and, in general, find new ways to connect to anything that interests you.

With this new found power comes a lot of responsibility. For one, you need to know who you are talking to, what you are sharing, and consider how this can impact you. For example, we mentioned earlier in the chapter that people you know can post anything about you, to include pictures and where you are physically located at any given time.

Also, when you join up for free social media sites such as Facebook, you have signed away your rights to your privacy. The owners of the site can use your data in any way they see fit based on the privacy policy you sign but probably do not read. As well, these site owners change this policy often and when they do, it’s usually in ways to loosen up the restrictions that they place upon themselves in regard to protecting your identity and data.

More and more people join these sites daily and there does not seem to be a stop to using them, they only grow more important as they displace tradition TV and radio as sources of getting information. Just like the Internet, when used for good, they can be wonderful additions to the Internet in the form of allowing those who wish to connect and communicate forums to do so. In the hands of malicious users, however, it too becomes a goldmine for those who wish to conduct surveillance on targets and gather information to be used in malicious ways.

It’s also amazing how generationally more and more people seem to feel; it’s ok to put daily updates about their life online for all to see, pictures of what they do, who they know, and, worse, specific data that can be used against them. There are many who become wise to how this can harm them either by being harmed or by learning too late how to protect their data, their identities, and themselves. However, these numbers are fewer than those who do not.

A good example of how this information can be used against you is when people say they will be on vacation for a week and send pictures of themselves on the beach while they are there. You should not be surprised that when your home is burglarized during that time, the first question to be asked is, did anyone know you were away? These same people stop their mail delivery and leave outside and inside lights on while they are away; however, digitally show no restraint in letting the world know they are not home.

Another common attack used for information gathering using social media is when an attacker steals your identity and poses as you on the site. For example, an attacker can take a copy of your picture of your profile, set up a new profile, and add all of your friends. They can say, “Sorry, I accidently deleted my account and need to re-add you” and if you do not log into your account frequently (which can also be figured out by stalking you online), post as you, talk to your friends, and conduct any number of attacks while you are away.

In sum, safety should be something you consider when using social media sites. As you can see, there are quite a few ways in which you can be stalked, information can be gathered about you, and, in some cases, used against you.

Scanning, Sniffing, and Mapping

Other ways to gather information rely on looking into lower levels of digital communications, primarily on the network. For example, you can use tools such as Wireshark, NMAP, and others to capture data and conduct packet-level analysis or port screening to gather and verify information about a target.

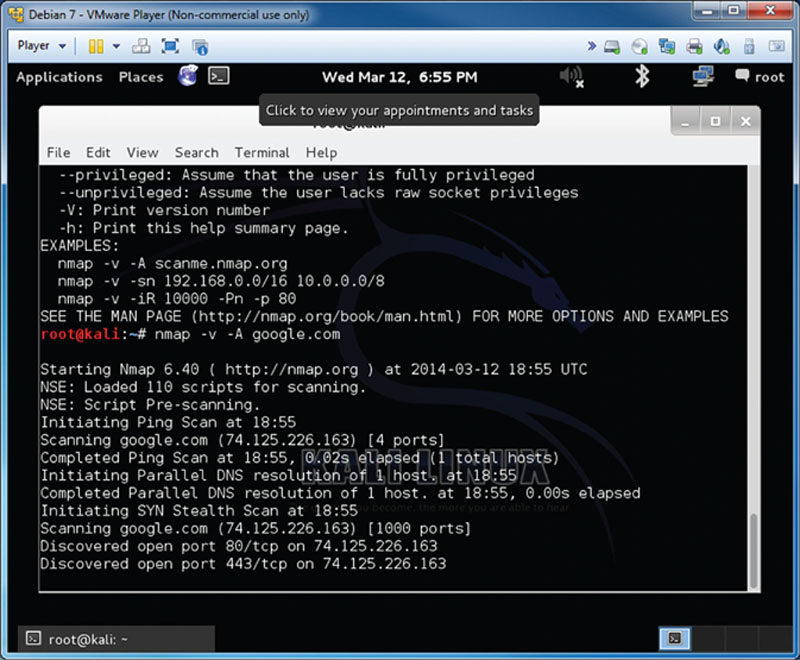

This type of information gathering requires you to be connected to a network and sometimes you will need to have access (or gain access) to unprivileged areas to conduct an attack; however, if you are able to you will be able to get the data you require. In this section, we look at using Backtrack to invoke NMAP to conduct information gathering on a host as seen in Figure 2.10.

Figure 2.10 Using NMAP.

In this attack, we simply load up NMAP and query the host we want to interrogate for information. It will reply back with specifics such as open ports. These open ports and IP addresses could potentially be manipulated for more information.

Although this is a simple example, more infiltration can be conducted as more information is learned. For example, an attacker may know that a specific port left opened may be something that they can penetrate and once they get to the next level of the attack, conduct another information gathering session to learn what else is open within the network.

Although this is information gathering at its lowest level, it should be considered a threat to you or anyone else because this is the same attack that can be conducted against any digital device using an IP address today. That means that any device you use that has an IP address can be probed for revealing information.

Wired and Wireless

Wired networks rely on cables and wireless networks rely on antennas using radio signals to attach to access points. Both eventually will connect to a higher level network that may ultimately connect to the Internet. That being said, let’s look at the inherent strengths and weaknesses found in both technologies.

When considering wired networks, we consider networks and devices that are cabled together with either copper or fiber cabling. The types of networks are more difficult to gather information on because it is not easy to crack into a cable to extract information from it. By doing so, you can ruin the cable and terminate the signals carrying the information. This makes it more secure than wireless networks and generally produces a higher transmission speed. Its main weakness is that it requires cable to be run from source to destination and is generally costly and harder to maintain.

Wireless networks provide flexibility and the ability to roam between networks, and most devices today use this type of technology. Mobile devices, laptops, pads, and other handhelds rely on wireless to provide and maintain a network connection. There are, however, major weaknesses.

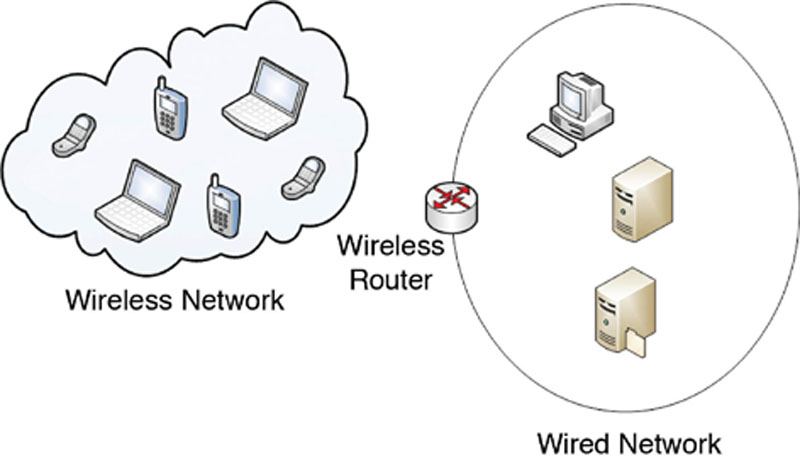

When wireless networks are used, they rely on radio signals that traverse through the air from source to destination and unless encrypted with strong encryption, they are easily captured, manipulated, and can be used for harm. Man in the Middle (MITM) attacks can be conducted where you can impersonate someone on the network. Information can be stolen and, in some cases, replayed against a destination system. A typical wireless network can be seen in Figure 2.11.

Figure 2.11 Wireless networking.

Infrastructure

Other concerns about keeping data private and safe revolve around the myriad of devices that your data transfers through. From your client–device (phone, laptop, PC), you can connect via a wireless access point, through multiple switches, servers, proxies, routers, security devices, and so on before your data reaches its destination. It is important to realize that every point in the network that your data traverses, that data can be stolen, read, intercepted, or manipulated. You would need to rely on the security teams entrusted to ensure your safety and privacy. This relies too much on the people in charge and is subject to human error.

Mobile Device Threat

The biggest trend today is the use of the mobile device. This includes (but not limited to) any device that you can use digitally that connects to a network for data. Global Positioning System (GPS) units, mobile phones, handhelds, pads, laptops, 2 in 1s, and many other devices today allow you to be flexible by being mobile. They rely on the ability to connect to networks (and thus the Internet) wirelessly and are as easy to manipulate by a malicious user because of their many flaws. For example, most devices allow you to install software on them from many sources. These software applications (or apps for short) are sometimes vetted by the mobile device provider (such as Apples attempting to provide a layer of security via the iTunes store) and sometimes they are not. That being said, once malicious software winds up on your device, you can likely be tracked, hacked, or worse.

Mobile devices use apps that allow for mapping of their exact location as an example. Apple uses Location Services to allow applications to provide additional functionality, but inadvertently also disclose your exact location at a specific time.

Data Threat (Metadata)

There is no bigger threat than being tracked online. You post a picture to Facebook and the next thing you know, you are a target. This can be done easily. For example, when using an Apple iPhone (or an Android device), you take pictures and information is stored in metadata without your knowledge. Again, when used for good, it serves as a way to archive your pictures and to know when and where you took them; however, when used for bad, it is a source for stalkers to pinpoint your exact location.

When considering the iPhone, you can adjust your privacy settings to turn Location Services off. An example can be seen in Figure 2.12.

Figure 2.12 Apple’s location services.

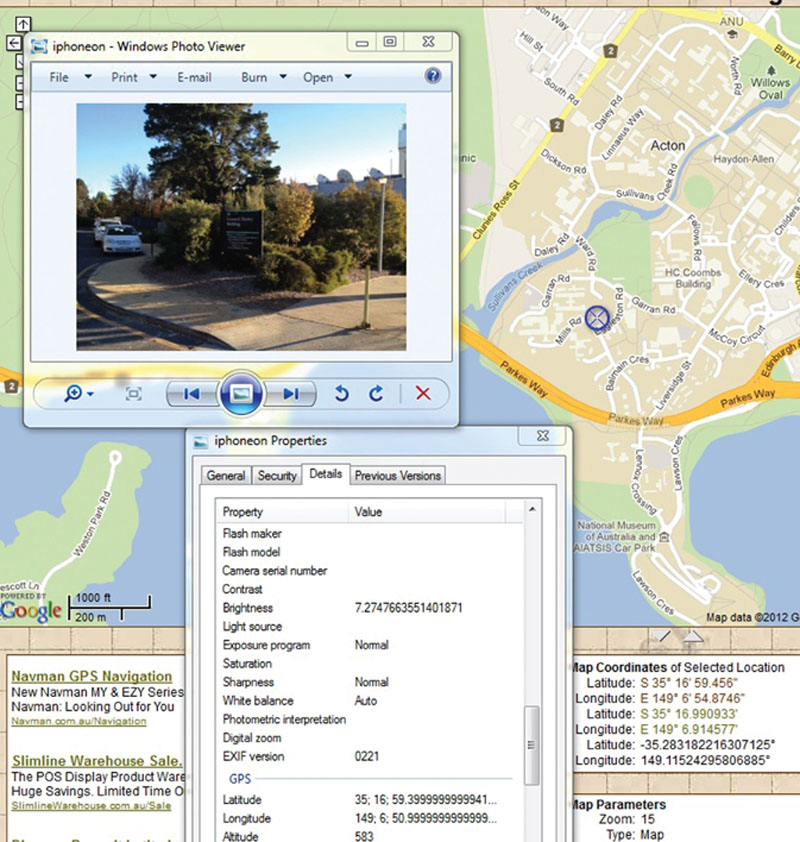

If left on, or if someone takes a photo of you (or your children) with it on, you are in a situation where that picture if in the wrong hands could expose exactly where it has been taken. An example can be seen in Figure 2.13.

Figure 2.13 Location mapping.

Here, if you look at the picture details, it will provide a GPS latitude and longitude recording that when plugged into Google map data, can provide an exact location of your whereabouts. A stalker across the world can find you and learn your location quickly and easily.

Physical reconnaissance

Our last section in the chapter will discuss physical reconnaissance and surveillance. Until now, we have discussed how infiltration, interception, and information gathering takes place within the digital world; however, some of the most successful attacks take place outside of it. There are many reasons for this – people are more overwhelmed and busy today and this could translate into not being aware of their surroundings, it could also be that people do not take into consideration that physical spying does in fact take place.

People will try evasive tactics to protect themselves online; however, they may not do so when traveling to work, for example. If they take the same path to work everyday, stop at the same 7-11 to get coffee, and park in the same spot, it’s easy to discern patterns. This is how some private investigators learn how to “tail” their targets.

In this chapter, we will talk about how information can be gathered on a target by physically following them, talking to them, and/or intercepting phone calls. It should also be mentioned that some of these physical information gathering attacks sometimes cross boundaries into the digital world.

Tailing and Stalking

One of the oldest forms of investigation, information gathering, or stalking technique is to physically follow someone without their knowledge. Private investigators when conducting an information gathering session will generally use video and film footage gathered while following their intended targets. Law enforcement will do the same when conducting an investigation. Attackers will do so to gather information about a target. Stalking a target is considered tailing or following them sometimes to gather information, sometimes to do harm. There is generally no other good reason to follow and stalk someone.

There is no way to explain how this can be done without saying the key is to be inconspicuous (aka sneaky). You must remain out of site, but not so far out of site that you lose sight of your target. There is a balance that must be maintained and if that boundary is crossed, you risk being “made.”

The only way to mitigate this danger is to be aware of your surroundings and change up your routine from time to time. Park somewhere different. Go to a different store. Take a different path. Practicing evasion when you pick up on someone tailing you is dangerous. You should not speed to get away and risk your life and those of others. If you are in danger, a trick is to drive to a police department or other location where you may be safe.

Social Engineering

Another tactic for information gathering revolves around a term called social engineering. What this means is, you trick someone through conversation to produce answers you need. For example, I place a call to you from a spoofed phone number that appears to you to be from a trusted source. I then tell you things that relate to you, us, or our conversation so that I can gain your trust. By asking specific questions and answers, I may be able to ascertain information from you needed to do another task, such as your account information to get into a personal website or bank account. This can then be leveraged into the digital world by exploiting the gathered information.

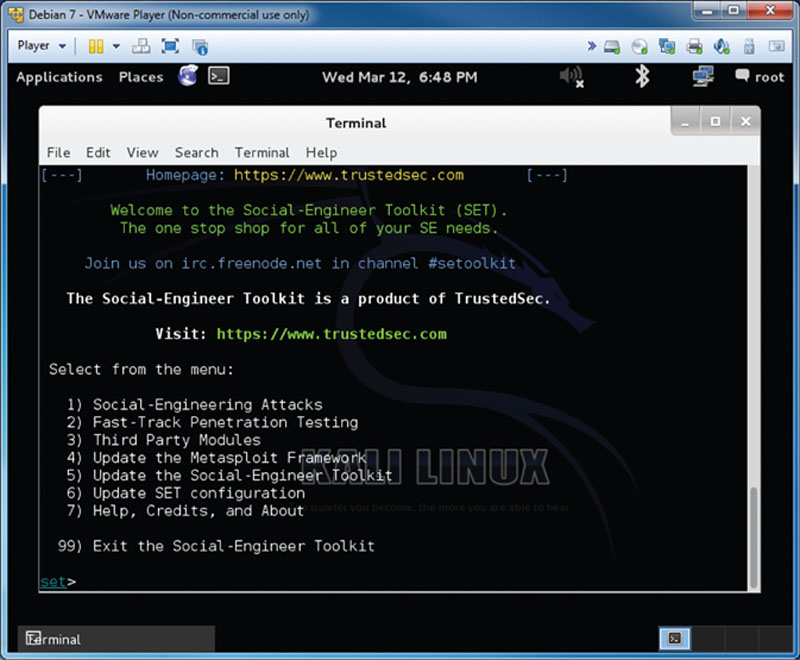

There are also software tools that can be used as seen in Figure 2.14. Here, Backtrack can load up social engineering programs that can assist you in performing such attacks.

Figure 2.14 BackTrack’s social engineering toolkit.

There are other attacks too that can be used to gather information such as dumpster diving. This would be to sift through trash to gather up data you threw away that may contain personal information that can be used against you.

Another form of attack is shoulder surfing, which is simply looking over the shoulder of an unsuspecting victim to view what they are doing such as entering a password or texting someone to gather information about what they are doing.

Tapping

Phone conversations are easy ways to gather information. Even easier is the ability to “tap” a phone line to get information. Before the digital revolution, analog phones were used en masse. They still, however, are becoming a thing of the past as more and more people leverage digital cell phone technology. Before we review how to tap digital phones, we should cover how analog phones are tapped.

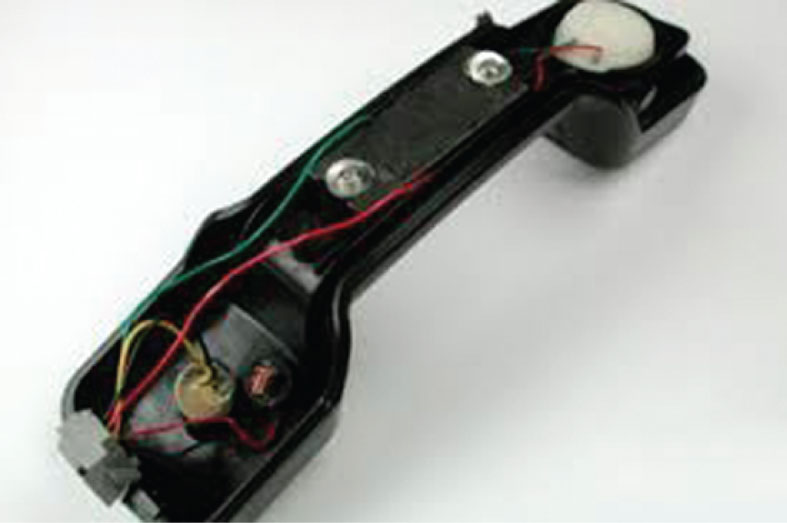

Wiretaps are nothing more than getting in between the phone source and destination and inserting a listening device in between. Since the phone system can be considered one long circuit from source to destination and creating a loop, all one would need to do is interject a load in that loop to tap it. An example of an older analog phone can be seen in Figure 2.15.

Figure 2.15 Analog phone tapping.

These copper wires contained in the phone and the loop itself are easily manipulated and information can be gathered rather quickly when conducting surveillance of a target.

In the digital age, phones transmit data over networks and sometimes over the public Internet. Mobile phones are now carried by most people today and because they are always in someone’s possession, harder to tap from the client side. From the server side, voicemail servers can be hacked, cell tower logs can be stolen, and data could be captured from source to destination and if unencrypted, read quite easily; however, intercepting it can be difficult.

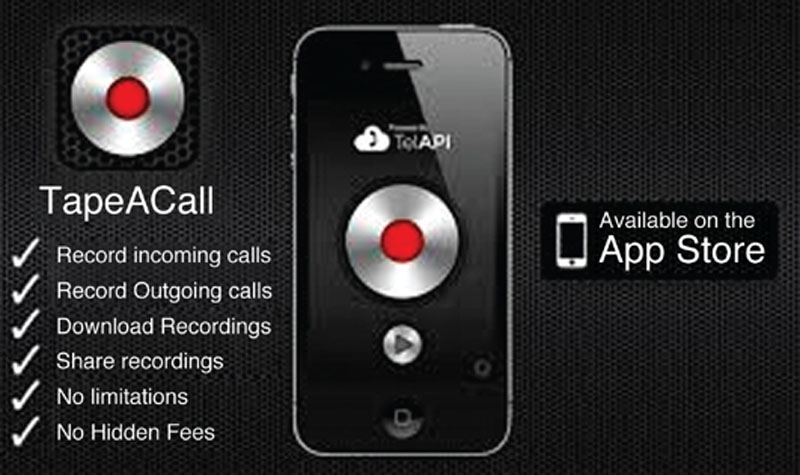

The easiest way to tap a digital device such as a mobile phone is to be able to get your hands on it. Once you do so, there are many software applications and tools as well as exploits that can be leveraged around it to listen in, track, and bug a device to gather information. Some tools, such as the one seen in Figure 2.16 called TapeACall can record a call without the recipient’s knowledge for later playback.

Figure 2.16 Recording iPhone calls.

It should be noted that there are other ways that law enforcement, government, spies, and attackers can “tap” into your phone conversations. Eavesdropping on calls is a quick way to gather information needed.

Legal and Ethical Concerns

In this section, we will cover a famous wiretapping case (case law and outcome) of how information gathering on a target online was brought into court and how it turned out.

The petitioner, Charles Katz, was charged with conducting illegal gambling operations across state lines in violation of federal law. In order to collect evidence against Katz, federal agents placed a warrantless wiretap on the public phone booth that he used to conduct these operations. The agents listened only to Katz’s conversations, and only to the parts of his conversations dealing with illegal gambling transactions.

In the case of Olmstead v. United States (1928), the Supreme Court held that the warrantless wiretapping of phone lines did not constitute an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment. According to the Court, physical intrusion (a trespass) into a given area, and not mere voice amplification (the normal result of a wiretap), is required for an action to constitute a Fourth Amendment search. This is known as the “trespass doctrine.” Partly in response to this decision, Congress passed the Federal Communications Act of 1933. This Act required, among other things, federal authorities to obtain a warrant before wiretapping private phone lines. In the case of Silverman v. United States (1961), the Supreme Court refined the Olmstead trespass doctrine by holding that an unreasonable search occurs only if a “constitutionally protected area” has been intruded upon.

At his trial, Katz sought to exclude any evidence connected with these wiretaps, arguing that the warrantless wiretapping of a public phone booth constitutes an unreasonable search of a “constitutionally protected area” in violation of the Fourth Amendment. The federal agents countered by saying that a public phone booth was not a “constitutionally protected area,” therefore, they could place a wiretap on it without a warrant.

Does the warrantless wiretapping of a public phone booth violate the unreasonable search and seizure clause of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution?

RULING

Yes

REASONING

By a 7-1 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with Katz and held that placing of a warrantless wiretap on a public phone booth constitutes an unreasonable search in violation of the Fourth Amendment. The majority opinion, written by Justice Potter Stewart, however, did not address the case from the perspective of a “constitutionally protected area.” In essence, the majority argued that both sides in the case were wrong to think that the permissibility of a warrantless wiretap depended upon the area being placed under surveillance. “For the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection… . But what he seeks to preserve as private even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected,” the Court stated.

Building upon this reasoning, the Court held that it was the duty of the Judiciary to review petitions for warrants in instances in which persons may be engaging in conduct that they wish to keep secret, even if it were done in a public place. The Court held that, in the absence of a judicially authorized search warrant, the wiretaps of the public phone booth used by Katz were illegal. Therefore, the evidence against him gathered from his conversations should be suppressed.

Retrieved from:

Summary

In sum, this chapter was written to open your eyes to the amount of ways in which information could be collected to conduct surveillance of a target. The digital footprint you leave everyday (you can’t see it but it is there) could be enormous based on how much you interact in the digital realm.

Unfortunately, we cannot isolate ourselves from living and doing so carefully and with due diligence will keep us safe; however, the method of attack and the growing landscape expanding the attack vector puts everyone at risk. By practicing safe security practices such as being aware of your surroundings, being careful about leaving or losing devices or other personal information, and checking to see if your systems are free and clear of malware are all good ways to be safe.

Information gathering will take place; however, it’s up to us to limit the amount of information that can be gathered. Stalkers gather information on targets, government agencies collect information on the public, their adversaries, and military targets, and corporations gather information on their competition – it is undeniable that this practice will not stop.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.