Chapter 1

Digital Reconnaissance and Surveillance

Abstract

This chapter covers digital reconnaissance and surveillance fundamentals and prepares the reader to engage in more detailed techniques in the remaining chapters. It covers why people spy, the motivations, the risks, and the rewards. It discusses fundamental knowledge needed to mitigate the threat of stalking and what information would be relevant for security analysts and the general public. This chapter covers current events, the damage that can occur, and the many methods in which spying can be conducted. Basic cybercrime topics are also covered.

Keywords

Reconnaissance

Surveillance

Spying

Espionage

National Security Agency (NSA)

Edward Snowden

Mobile Technology

Public Internet

Social Media

Video Surveillance

Digital Forensics

Terrorism

Stalking

Cybercrime

Penetration Testing

Law and Ethics

Digital reconnaissance and surveillance

Today, the world operates on a digital landscape. Wearable technology is the latest buzz word and everyone seems to be connected via their phones, pads, and laptops. Virtually everyone everywhere is becoming more and more interconnected and sharing data and socializing. Using this medium has become the norm. While the world continues to grow digitally, so does the risk of exposure. As the landscape grows exponentially, so does the threat of those who would, and will abuse this medium for their own gain.

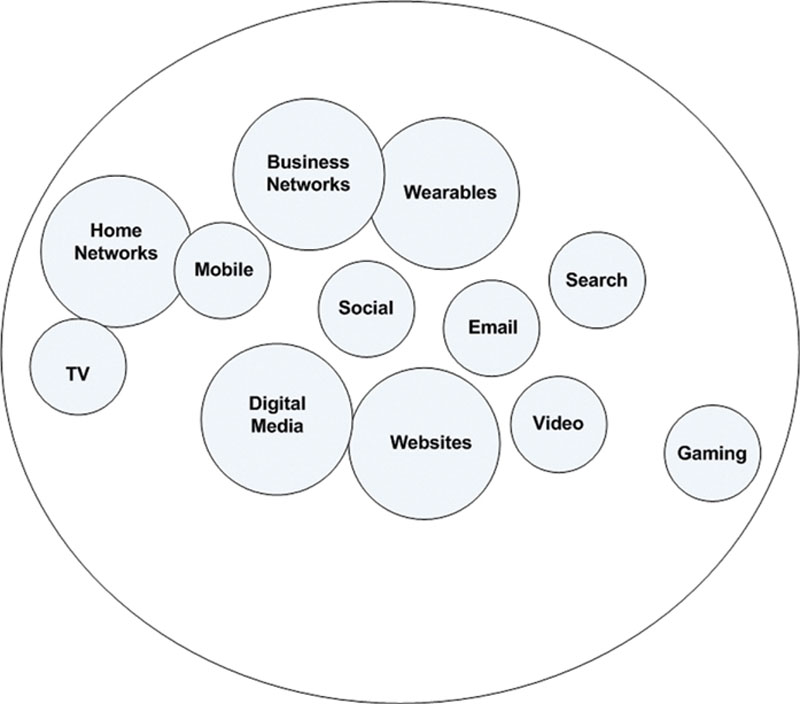

Modern societies cannot hold back growth and innovation because of fear; those same societies must learn to overcome challenges of a growing interconnected world as seen in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Viewing the digital landscape.

Because technological advancements grow exponentially, the security innovations must encapsulate and work within them. Security is not a new consideration; it is an age old practice applied to new situations such as a growing digital landscape.

Reconnaissance and surveillance have been practiced for centuries, primarily as a way for militaries to conduct observation of enemy activities and monitor targets to gain strategic advantage. Reconnaissance and surveillance teams would go out to gather information about enemy activities in hopes to find out location information, size, and strength of their targets and/or to place targeting information for incoming strikes.

Digital reconnaissance (or digital recon for short) is the “digital” form of what these teams or individuals do, except primarily in a computer-based world. These experts perform many of these same basic functions of their military counterparts and the target could be strategic advantage, financial gain, leverage, or to place targeting information for more attacks in a corporate or private landscape. The landscape is not the traditional battlefield, but the cyberworld where computers and mobile technology can be manipulated, video cameras can be hacked into, and databases of personal information can be stolen to gain strategic advantage.

Not all who perform reconnaissance and surveillance activities have bad intentions; some perform these activities in order to protect. In recent news, the National Security Agency (NSA) has been filtering data of the Americans and others in the name of national security. Because it wasn’t disclosed and seemed to overreach, it was immediately brought into questions by the American public when it was brought into light by Edward Snowden, an employee who worked with the NSA and leaked how the NSA was capturing inappropriate data. The threat of government’s spying on individuals is not new; however, it seems to have grown more post 9/11 because of the threat of terrorist attack, the assembling of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the United States, and the ability for many to use technology as a way to gather information quickly about anyone or anything.

In this chapter, we will detail the fundamentals of digital reconnaissance and surveillance, provide some history on the topic, and set the tone for the remaining chapters where we will go into detail on how these activities take place, how vulnerable we are, and how to fortify our defenses and mitigate risk on a more personal level.

Art and History of Spying

As we have just discussed, reconnaissance and surveillance is not new; it’s been practiced for centuries. The term “spying” may come to mind when you read about or watch movies where a “spy” is used to capture information about a target. In this book, we will use this term interchangeably, so when the term spy is referenced, we use it to explain the person or activity of collecting and reporting information on a specific target.

What is surveillance? The word surveillance comes from the French word “watching over.” Surveillance involves monitoring persons or locations to identify behaviors, activities, and other changing information. This will be the primary topic and focus throughout the book, covering the current landscape and attack vectors. Learning how to mitigate and defend against digital surveillance is tricky; today almost everything you do is captured on camera or tracked. We will cover more on this topic as we progress through the book; however, understanding the passive and the aggressive form of surveillance is important.

There are different forms of surveillance to include adversarial surveillance that is to gather information in preparation for an aggressive action and likely criminal in nature. Examples of adversarial surveillance are terrorism (domestic and international), destruction of property (logical or physical), and other crimes against individuals of entities to include theft, stalking, and espionage. Espionage (which is used interchangeably with spying) is defined as the practice of spying on or spying by governmental and military entities to gain information.

Surveillance has also advanced to the point where unmanned aircraft (typically called Drones), as seen in Figure 1.2, is responsible for conducting “spy” missions to gather data and information on targets. This has brought about a large amount of controversy about how privacy is impacted and what legal issues arise from such activity.

Figure 1.2 Security drone.

One of the most historical legal concepts of spying is the Espionage act of 1917. This highly outdated and misused law does not fully protect those who are charged with spying. Cybercrime is not covered, security clearances are not covered, and it is consistently becoming more and more important in the realm of prosecuting criminals at the highest levels of government. It also brings to light what are the legal implications of spying on your neighbor, such as using their wireless connection, and infiltrating their home. What about the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 that prohibited the storing of certain data on others. As we will learn for decade’s, protection has been put into place to draw specific boundaries to keep privacy of citizens in check; however, this has brought about many legal challenges along the way. In this chapter and throughout the book, we will cover these legal aspects alongside the technical how to and defense tactics you need to put into place for safety and security. You will see in this book, as we progress through the chapters, and looking at how digital spying is conducted, you will find that many of the old tactics used outside of the digital realm still apply. As an example, stalking digitally can also lead to traditional stalking and vice versa. Understanding the concerns and risks of both are relevant to understanding the threat as a whole.

This does not mean that any person or team that conducts surveillance is a threat. Investigative, forensic, and security teams today conduct investigations legally and may require a warrant or some form of legal backing to conduct any type of information gathering; however, not all need to operate within these boundaries. Therefore, it’s important to understand some legal concepts when either you are the victim of these activities or, if perpetrating an attack, what you may or may not be held liable for.

Threat of digital reconnaissance and surveillance

What is at stake? Currently, much is at stake. Your privacy is at stake. Your safety could be at stake. Your identity can be stolen. You can be impacted financially. As the digital landscape grows, so does the threat exponentially. We will cover each of these in depth; however, it’s safe to say that the threat is very real and the need to understand it and protect yourself should be considered and practiced.

The threat of digital spying is also growing at a rapid rate, generationally, and more and more are creating an online footprint. As more people get mobile devices and attach to the public Internet, there are more opportunities for attackers to conduct surveillance on selected targets.

Your identity can be stolen. You finances can be impacted. Your safety can be threatened.

To understand this concept in more detail, we need to consider the size, depth, and breadth of the threat landscape.

Threat Landscape

As mentioned before, threats grow exponentially. The math is simple. As more people connected to the public Internet via a growing number of devices to include mobile phones, laptops, wearable technology, and pads, the number of possible victims also grows. The attack vector also extends.

The Internet fueled by search engines, social media, and the ability to retain all that it collects is a digital spy’s goldmine when doing reconnaissance work. Considerably, one of the biggest threats today on the Internet is in the form of search engines and social media. You can virtually learn a person’s history, what they like, their location, and who their friends and family are. You can learn where they work. You can even track their movement day by day. This is a reminder that George Orwell’s book “1984” may indeed have come to 2014 and Big Brother is watching. In fact, this book may turn you into a Winston Smith, looking for ways to evade Big Brother’s roving eye! Today’s roving eye looks more in line with the millions of cameras that can be found in stores, businesses, and home across the world as seen in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Digital surveillance camera.

Search engines are so far one of the first (and easiest) tools to use to start reconnaissance on a target. You may even attempt to safeguard your personal information or the websites you use may attempt to safeguard it; however, let’s take a look at how easy it is to gather information on a target.

In this example, we will look at the growing world of online dating. One would think that by going online and filling out a profile on a website that is marketed as safe, one could simply find and meet their perfect “match.” Before the online dating craze took hold, traditionally a person may get a “reference check” from a friend of family member about a person who may be right for them. They may meet somewhere and get to know each other, perhaps at a school, work, or a venue. They may talk on the phone and get to know each other. Today, you simply need to create an online profile and sit back and wait.

You may think it’s safe; you are not identifying yourself by last name, you may not be putting up a picture, or you may lie about who you are. But what if you were honest? What if you put a few key pieces of information up like your first name, last initial, your occupation, and the town where you reside? This is all that is needed to give a spy (or worse, a stalker) enough information to begin to track you in a search engine. For example, Rhonda K., a Horticulturist who resides in Kissimmee, Florida, may be enough to find your LinkedIn profile. Now, there is enough to begin to track more information about you. As we progress through the book, we will learn how to dig deeper and find more information; however, this is enough for now. To show you the “threat landscape” and how deep and wide it goes. Rhonda may have just been divorced and looking for a safe way to date that fit into her busy lifestyle; however, by attempting to remain anonymous while she tested the online dating waters may have exposed herself to stalking.

Social media is also another treasure trove of information. By simply infiltrating someone’s social sites, you may be able to launch attacks directly against a victim in the form of bullying, stalking, and worse, criminal behavior. With sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Linkedin, one could conduct surveillance and reconnaissance of a target and gain information such as identity, occupation, location, movement patterns, and more.

Mobile technology has widened the threat landscape by giving each and every user of a mobile device a way to track their every movement. A stolen, hacked, or bugged phone can provide information on a user’s identity, location, movement patterns, and communication history. Digital pads from Microsoft, Google and Apple are also commonplace today and they store just as much information. What makes these devices all the more enticing to someone who is tracking you is, they are not left at home! If a phone is bugged, normally it never leaves the owner’s side providing data on everywhere they go, everything they do.

Stationary devices are just as much of a threat now as they had ever been. Computers are used at work and at home and if exposed locally or remotely, can also provide a great deal of information to those collecting it. Other stationary devices such as video cameras are now found everywhere. While driving, cameras track your movements and report location to a centralized collection system. While walking into stores, schools, work, or now in personal homes, cameras track your movement in the name of safety and security. What if those cameras were used for reasons other than good?

A good example of use can be seen in Figure 1.4. Here, we see traffic camera’s providing services such as allowing citizens to see what a major roadway may look like to pick a better route to work, one that may be less congested or accident free. It provides a way for law enforcement to maintain safe driving patterns by ticketing those who break laws such as running red lights. It allows law enforcement agencies to track a child abductor by tracking a license plate through such cameras. However, these systems can be quickly misused.

Figure 1.4 Traffic cameras.

We also need to consider the digital threats that only add on to the already existing threats that existed prior to the existence of the public Internet, mobile phones, and computers. The reason why it’s pertinent is that you understand the threat landscape is because it is growing. It’s everywhere you go, everything you use, everything you touch, and everything you send digitally. Nothing is safe, nothing is untraceable. In this chapter, we learn how to safeguard as much as possible to ensure that you do not easily become a victim to surveillance and reconnaissance.

Why spy?

Now that we have discussed the foundations of digital reconnaissance and surveillance, let’s look at some of the current newsworthy high profile stories of how digital spying is affecting the world. It is difficult to turn on the news today and not hear about the NSA and Edward Snowden, to date, one of the biggest news stories around covering the topics of digital spying by the American government on its own citizens. Other news stories will be covered; however, this is one of the biggest stories to break the new media about spying in the past few years.

We also need to understand why spying takes place. What is to gain? What is to lose? Spying is done on purpose … there are reasons someone spies on another person, organization, or entity. Those reasons will be discussed in depth in this chapter. It’s important to understand the motivations behind those who spy, by doing so you may be able to proactively know when you are at risk.

We will also cover the details on who the bad guys are and who the good guys are and how the lines blur. Not all spying is done by a stalker, an ex-boy or girlfriend, or by a husband or wife. Not all spying is done by organizations looking to achieve competitive advantage over other entities.

Some surveillance is done simply to protect interests. For example, military organizations perform surveillance and reconnaissance missions to gather information about an entity. Some governments perform these functions as a way to protect its citizens. As mentioned above, however, those lines are easily blurred.

In this section of this chapter, we will also cover the fundamentals of digital forensics. Since we will be covering investigations (both criminal and noncriminal), it only makes sense to discuss the science of digital forensics.

NSA and Edward Snowden

In terms of spying, surveillance and reconnaissance, and intelligence collection, the NSA is an intelligence agency that operates under the Department of Defense (DoD) for the US Government. The NSA is tasked with collecting intelligence to keep the country safe.

The NSA is allowed to operate in a manner that may seem inappropriate in hopes to safeguard the United States and its interests abroad. How the agency does this is through mass surveillance of communications, phone records, Internet transactions, and e-mail. It collects this data, filters it, and software mines it for key words and other triggers.

So why so much news media about the NSA lately if this is what they were tasked to do?

Edward Joseph Snowden, an American computer analyst working as a contractor, was accused of allegedly leaking top secret information about the NSA who he accused of spying on the American citizens by collecting data on them as seen in Figure 1.5. He claimed that all data being collected seemed to fall outside of the boundaries of targeting individuals who may be deemed a threat. Instead, the NSA was collecting and filtering data on everyone who communicated within the United States, as well as outside of it.

Figure 1.5 Edward Snowden.

Although some of the biggest news during the printing of this book is revolving around Edward Snowden and the NSA, this is not a new topic. It should not be shocking, although it is. As mentioned earlier, for centuries, governments and military organizations have been performing intelligence and counter-intelligence operations. This is also not the first government scandal to take place (America or otherwise). The secret Five Eyes organization made up of five ally countries (made up of countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia) routinely share information among each other. Edward Snowden released that the United States had been sending Israel unfiltered data to a foreign country that contained private information about the US citizens. Had it not been for the current leak of information, this practice that has been going on for decades would not be of personal public interest because it would not have been a top story in the news.

Another interesting story to consider would be how the US public is surveilling its own government. When the story of Wikileaks broke in the news, not only was it very popular but also it became the subject of a newly released movie. Wikileaks released data of US military missions online for all to see as seen in Figure 1.6. This was a very controversial move by the citizens to show that spying can also be dangerous to the government if they do not protect their secrets, and secrets that are made public can cause a government major problems such as put agents at risk or destroy trust.

Figure 1.6 Military surveillance.

So what is breeding paranoia and fueling fear that tests public trust? The same question may come up as to why I decided to write this book and perhaps why you have decided to read it. The answer may be simple … it may be that there is a lack of public trust these days, now more than ever. Perhaps, it is because there are too many stories on the news about how easy it is to hack into social media accounts and conduct cyber-bullying. Perhaps, it is because identity theft has become a common crime. Perhaps, it’s because everywhere you turn there is a video camera recording your every move, or because everyone carries a mobile device that can capture the moment and post it online for the world to see within seconds. It may be an answer that is more radical it may just be that fear and paranoia make a great news story and ratings have never been higher. No matter what the reason, the threat is real, and in this book, we will cover how to defend yourself, mitigate risk, protect your identity, and close attack vectors whenever possible.

Public Trust

Honestly, everyone likes a great spy novel. Famous movies are abundant and 007 James Bond is a household name. We get excited about these movies and we read spy novels, but what if you were actually spied on? How does it feel to be excited about seeing a spy in a movie use their cool gadgets developed for espionage? Then to find out someone was stalking you online and following you around without your knowledge after tracing your movement patterns? It is interesting that a culture excited about the prospect of excitement in the world of spying would be polling so low when it comes to the fact that they have become the stars of the latest spy thriller.

These questions come down to public trust. Public trust is low these days and while writing this book, it can be considered to be at an all time low. In recent Gallup polling, it is no wonder folks do not trust their governments – they are polling and showing results that public trust is a cause and effect based on how negatively the news is portraying governments involved in what they have been doing for a long time.

The news media is a large distributor of propaganda to sell products and gain views from those who are willing to view their products as seen in Figure 1.7. The term “spy” is used often to generate fear, probe those who distrust or are unsure, and question their privacy in a way to build paranoia to sell products. This doesn’t make what they are saying is untrue; however, it needs to be viewed in a way that is educating and not in a way that causes citizens to worry about their privacy, or in a way that causes them to fear everything and everyone around them.

Figure 1.7 Newspaper headlines denoting spy activity.

That being said, let’s move away from the world of international spies and military covert operations and move into the day-to-day operations most of us live today – our personal lives. Public trust in each other and our neighbors, the people we work with, and our families and friends should not be rocked by government scandals and daily news stories on how your privacy is not safe. The truth is, your privacy may not be safe and it’s up to you to safeguard it. We will teach you how to do so in this book.

So why disclose this information to you in this chapter? To show you that spying is nothing new, nothing uncommon and seemingly done often without concern for the law. It’s mentioned to explain to you, the citizen, how you can protect yourself from spying at any level, how you can be spied on, and how you can better protect yourself from these actions.

Let’s say you do not personally own it; however, you get it as a service through your ISP. You need to understand that other people are maintaining it, monitoring it. How can you trust them? How can you ensure that your private life is not being watched by someone you do not trust? What happens to that trust when the entities monitoring your cameras have a security breach? These questions are hypothetical to build critical thinking among you and your family to consider, for each benefit there could be a consequence.

Cybercrime

So now that we covered government and military, what about the local and the state laws against criminal behavior. Can you be stalked online and charged with a crime? Obviously, it’s hard to charge an entire government that has been given carte blanche to “spy” in order to keep the public safe, what about the public itself?

Cybercrime is crimes committed using a computer and/or a computer on a network. It’s a simple definition; however, there are many considerations such as does it take place on workplace computers? Over the Internet? Does it take place using e-mail, mobile phones, or within chat-rooms owned by a service provider?

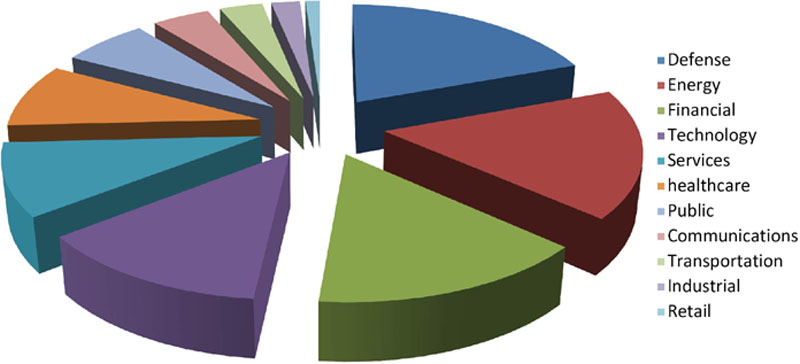

This becomes important because if someone is caught spying and it’s over the Internet from another country, how is the crime prosecuted? It can be conducted over the public Internet that then makes it cross-border crimes since it touches the global landscape. For an example of the size and scope of cybercrime activities, please refer to the chart as seen in Figure 1.9.

Figure 1.9 Cybercrime activity.

What is important to consider is that these are in fact crimes and because of that, there is a process involved. Criminal activity if caught must follow specific protocols operating within the realm of law. After these crimes have been committed, normally digital forensics are used to substantiate the evidence brought to trial, as industry experts comb over the computers, phones, and networks to preserve evidence and bring it within the court of law.

As we mentioned earlier, espionage can also be considered a major cybercrime. This ties into the motivations those have to conduct cybercrimes … a major one would be financial theft, another identity theft. So why would someone do these things? What are their motivations?

Why Spy? Motivation

At a bigger level, we mentioned why organizations, governments, and militaries spy. Although we do not cover the details of all computer-related crimes, we do cover some of them here so you can understand that stalking someone online is no different than stalking someone at a public location. We do cover spying in general so that we can teach you how to protect yourself overall; the best way to understand how to protect against someone wishing and willing to do you harm is to understand why they want to do such a thing.

At a macrolevel, reconnaissance and surveillance are performed by the government agencies and the military for security and safety reasons, to gain tactical advantage and to thwart terrorism. The reasons why people spy on the microlevel are many; however, to create a small list of some of the most common reasons, you will find that whether at the macro or microlevel, leverage, advantage, and gain are some of the most common threads that bind any reasoning to any who spy.

Consider a couple divorcing and is in the middle of a legal custody and financial battle. You have heard it before, to gain advantage in the court (tactical advantage), one of the injured parties may request the assistance of a private investigator (PI) to “spy” on the other to learn of their activities. Those activities if shown to shed light in an unfavorable manner in the court may give the other party leverage.

Consider a small business opening up near another business of the same kind and the two entrepreneurs visiting each other’s establishment in order to gain competitive advantage. Of course, they do so without each other knowing who they are. Taking this into the digital realm, these same entrepreneurs visit each other’s web properties to perform the same tasks. Consider that one of these parties chooses to deface, discredit, or defraud the other in hopes of injuring their reputation.

Consider someone who realizes that their spouse is looking through their phone when they are not around to see what they are up to, who they are talking to, what sites they have been to, and what their e-mail content is.

Consider an author publishing a new book that directly competes with a title of similar content and launches a smear campaign using the comments section of the site in which it’s sold to discredit the title.

Consider a high school student who is consistently picked on (bullied) and only way to get back at those who are conducting these actions launches a cybercrime against the perpetrators, for example, hacks into and defaces their public Twitter page.

What if an ex-boyfriend wanted to stalk an ex-girlfriend and posed as someone else on Facebook to track, monitor, and interact with her? Facebook and other social media site as seen in Figure 1.10 are a large source of controversy today in regard to privacy. These sites are easily used to provide portals into private lives and give those who use them for the wrong reason to track you, find out where you live, when you take a vacation, and where you work.

Figure 1.10 Social media concerns.

At a more microlevel, an individual can spy to learn more about another person. For example, if someone you worked with wanted to get to know more about you … instead of just asking you or trying to get to know you, they search for you online in a search engine.

The motivations are endless, they are many. Legal reasons, divorce, leverage, financial, theft, revenge … the list goes on and on. This is why people may decide to conduct their own investigations on others, why they would consider spying on others. Make no mistake; however, most of these activities are spying and many of them may be considered a cybercrime.

What Is to Gain? Reward

When someone spies it’s always to achieve a specific goal. Whether the goal is to learn information, take photos, or document activities, this is where spying and actual crime can become a challenge to define. It is easy to understand if you split the two into two separate activities. Surveillance is conducted to gather information about individuals, organizations, businesses, and infrastructure. It may be gathered in order to commit an act of terrorism or other crime. At both the macro and microlevel, there is much to gain. There are massive rewards.

In the United States, the banking and finance sector accounts for more than 8% of the annual gross domestic product and can be considered one of the major arteries of the entire world economy. Spying on these targets at any level to produce information to sell or to produce intelligence for a digital attack can be extremely rewarding.

At the microlevel, gains can be just as rewarding to those who wish to do wrong. For example, you want to find out if your neighbor’s wireless is open for use so you do not have to pay for yours. You do some reconnaissance work and scan the area to find a signal. You attach to the wireless Service Set Identifier and bypass the password configured. Later, you find that you are able to attach to the main network and connect to their in-home video surveillance security system. Some would think that being able to watch their neighbors unsuspected would be a reward.

In another example, pictures were scoured off the Internet from young girls taking “selfies” that provided their location (possibly home address) within the metadata of the picture. This enabled those who wish to do wrong the ability to track and possibly stalk these girls.

As you can see, there is much to gain especially by those with ill-conceived notions. That’s where the possible crimes take place and afterward, the investigations into those crimes possibly as part of a case in the court of law.

Digital Forensics

Digital forensics is considered the investigation work done after a crime is committed on digital devices and networks. Although we have only described a small handful of possible crimes that can take place in the cyberworld, it’s important to understand for the purpose of this chapter that as you commit cybercrimes, they can be detected, thwarted, and brought into the court of law. For example, if you wanted to use an application to track someone using their phone, if that phone winds up in the hands of a digital forensic analyst, it’s likely that they will be able to produce that software and show the cyberattack in detail in the court of law.

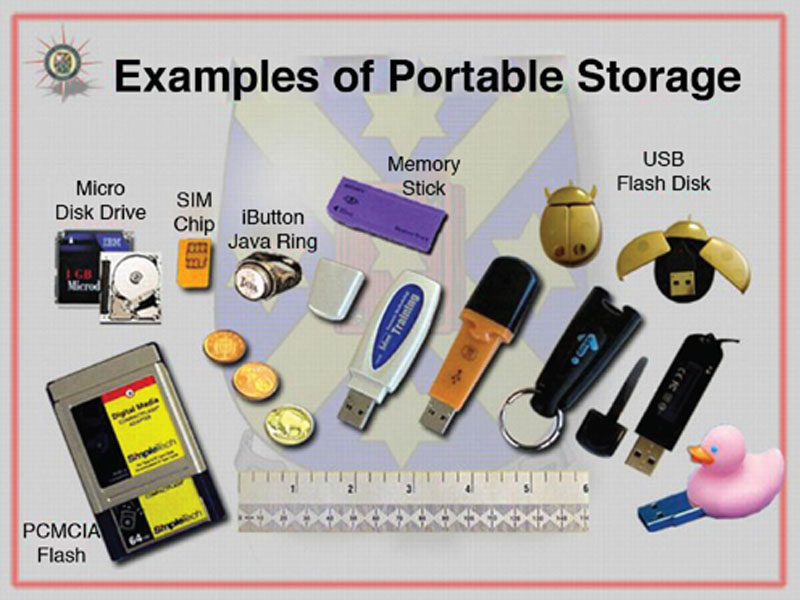

Digital forensics can be used for surveillance as well. As we will learn, some of the data gathered from your devices memory, logs, and storage devices can be very revealing. These items can disclose where you have been online, sometimes where you have been physically, what you have done, what you have said, and what you have stored, and give those who are performing surveillance a bird’s eye view into your digital behaviors. An example of the amount of storage devices that data can be gleaned from is seen in Figure 1.11.

Figure 1.11 Portable storage devices.

These same digital devices can be brought inconspicuously into your home or business and data from your devices can be transferred onto them without your knowledge.

One thing to note is that digital forensics can recover for the investigative purposes almost anything on a computer or network system as long as it has not been tampered with. For example, information kept in memory may be lost if the device is turned off. Although a major discussion on forensic science falls outside the scope of this book, we will in fact cover forensic specifics throughout the book when discussing relevant topics.

Who spies?

We covered the nuts and bolts of why reconnaissance and surveillance takes place. We discussed the legal aspects of it; however, before we end this chapter and move into the details of how it is conducted, we should take a close look at those who spy and specifically, if they are doing it for the right or wrong reasons.

Who spies? It’s easy to just say “everyone” at some level because of human nature and how people can be curious; however, we will break down key categories so that you can understand not only who, but why. A good saying is “Curiosity killed the cat”. Its human nature to take interest in things they want to know or learn about; however, ethically there are boundaries.

The government spies in the name of national security. The military will spy to conduct covert operations.

Organizations spy to gain competitive advantage. The public spies for many reasons to include harmless curiosity all the way to conducting major crimes.

One topic we did not cover is the list of diverse professionals who work within the digital realm to conduct investigations, surveillance, and reconnaissance work on a daily basis. We just recently covered the legal aspects of conducting surveillance work and touched on the role of PI; however, there are many other roles that conduct surveillance work, investigation work, and not all of them are “bad guys.” Some of them are and we will cover the distinctions throughout the book when we delve into the actual “how” it’s done; however, to start, lets take some time to review the professionals today who conduct digital surveillance and reconnaissance work and the reasons they do.

Professional Roles

Digital surveillance and reconnaissance is conducted by many. As we have discussed earlier, the military, the government, your neighbor, and your co-worker may for some reason or another, wish to gather data or intelligence on another or another entity for specific or even no-specific reasons.

There are those, however, who work professionally in the field. These professionals are also experts in working in the digital realm or technology. Digital forensics, cybercrime investigators, penetration testers, and law enforcement specialists are only but a few of the diverse offerings within the field of digital security.

What we will not cover here that we have already discussed in this chapter are military and government agents who conduct reconnaissance and surveillance work for gathering intelligence.

Hackers (White, Gray, and Black)

One of the biggest threats today in the digital world is the “Hacker,” who traditionally manipulated your computer, mobile, and video systems so that they could tamper with them, gain access, or acquire information from them. These same folks were able to create malware (malicious software) to perform these same functions; however, some of these programs were able to track your activities, impersonate you, and or steal your identity. What a hacker does is broad; however, it needs to be understood that the malicious form of the term hacker has been rebranded.

Black hat hacker’s are those who wish to do harm, are malicious or operate in an unethical manner. White hats are considered to be hackers who are non-malicious. White hats are generally computer system experts who work in the security field to find problems with systems that their malicious counterparts would look to expose for financial reasons, leverage, or simply for fun. Gray hats are said to cross both black and white boundaries and generally will not be overly malicious.

There is a reason you need to understand why these types of experts spy; they spy to gain something and unfortunately since they may happen upon your computer system with your personal information stored, they may collect it for their own personal use or to sell for a profit. They may attach to your systems without your knowledge and conduct their operations in a clandestine manner in which you may not detect.

Digital Forensics Examiner

As we discussed earlier when covering the world of digital forensics, there is much to be gleaned from digital devices and most, if not all, activity can be found and brought into a court of law to bolster a case as evidence. Unfortunately, if you are the malicious party, it’s likely that you will have all of your activity presented unless you masterfully know how to cover your tracks and/or dispose of evidence correctly.

These experts are often brought in to testify as experts in their field and present evidence in the form of data, logs, and provable activity. Digital forensic examiners use special tools and software (Encase is one of the most commonly used) to scour a computer system or device in order to find data and, as long as the crime scene or evidence is untampered with, can be used to show all activity of those using such systems and devices.

Cyber Intelligence Analyst

Intelligence agents (or analysts) are those who work in the Intelligence field and typically are employed by military and government agencies. When Intelligence is gathered on a target, these individuals or teams review and assist with the activities revolving around building cases, fighting crime, stopping malicious activities from taking place, and more.

These experts work on cybercrime cases and assist with the analysis of the data collected. For example, if a Virus was used to steal government data, these intelligence experts may work with developers, companies, other software teams, and so on to assist with reviewing the findings and assisting them with the stopping of the criminal behavior taking place.

Cyber Security Engineer

Security engineers (or analysts, in general) work within the field of information technology security and typically assist with the design and assembly of digital computer security systems. For example, they may be firewall, intrusion detection/prevention system experts who understand access control, authentication, and accounting in depth.

In regard to surveillance and spying of and on systems and people using systems, these experts are those who are in charge with building and engineering systems that offer security to prevent unauthorized access to private networks, computers, and systems.

Penetration Tester

Penetration testers (or pen tester for short) are charged with testing access of systems that have already been engineered. These experts verify that access cannot be gained, and if it is, they provide reports on what needs to be fixed. It would be extremely difficult to spy on a home through their video cameras if this weakness was considered, tested, and then locked down post test.

They use software such as Backtrack, Nessus, and others to verify that access cannot be gained unless permitted and exposure is limited. They mitigate the possibility of problems taking place by exposing that they are problems to begin with and give such findings to those charged with locking open holes down. They are also highly employed by those looking to ensure that systems and networks that are to be and remain compliant are in fact configured correctly to be compliant to policy.

Private Investigator

Private investigation is a form of surveillance work. We discuss it here in this section of this chapter coincidentally; it’s a common form of work performed to gather information on a target. Private investigation is a trade where trained professionals conduct surveillance work for clients as per request.

A PI is a professional who performs investigations. Although we have touched on this topic throughout the chapter, PI’s are responsible for conducting private investigation for those who request their services. They often conduct surveillance activities for those who hire them and can be considered a private detective conducting investigations for criminal cases, civil cases, and for collection of evidence. Sometimes referred to as a private eye, these professionals commonly work for attorneys who need to collect evidences to support legal cases.

They can (and often are) hired to spy on individuals to bolster cases with documented evidence commonly produced by video and camera footage (Figure 1.12). Today, professionals undergoing these work activities are generally licensed to do so and operate within ethical standards.

Figure 1.12 Private investigation.

Law Enforcement

Law enforcement professionals (such as police, agents, and detectives) are commonly used to conduct and/or stop surveillance activities. If a crime is suspected, for example, detectives may be called in to open a case and start to collect and review evidence. To do so, these experts must at times do reconnaissance and surveillance work in order to build cases and report on them, and/or use such evidence in the court of law.

Legal and ethical principles

Until now, we have talked about a lot of scary stuff and how it relates to the court of law; however, there are many factors to consider when it comes to digital spying when brought in front of a judge. We know what experts are counted on to bolster cases and we know the types of malicious characters who may be committing crimes. We now know that there is a blurry line separating government and public activities and some of the legislature created to create clearer lines to follow.

To close this chapter, we should discuss legal and ethical principles revolving around surveillance activities. In the remaining of this book, we will cover surveillance at a more personal level; however, it’s important to understand that for those committing spying and stalking crimes (for example), there could be a punishment. As easily as it may be to use the digital landscape to conduct your crime, it’s as easy to gather the evidence of it happening.

Ethics

Ethically you should not use any of the information learned in this book to conduct a crime. It is here for one purpose, awareness. The goal of this book is to help security professionals in the field and/or the typical citizen remain aware of digital surveillance issues taking place today and to assist those parties with providing a way to be aware of them, mitigate them, and protect against it. It is by no means a book that shows someone with a vengeful heart a way to conduct such unlawful activities.

Ethically, you should always consider that there are those with ill intentions out in the world and you should learn how to protect yourself against them, not become one of them. You should also consider that since you are protected by laws, so if you do suspect you are a victim, you should not retaliate or counterattack. This behavior is not only counterproductive and inflammatory but also could be illegal and used against you.

The Law

With the growing digital landscape, cybercrime has grown just as quickly as the networks, systems, and applications have. Because of this, legally, lines have been blurred as cyberlaw has attempted to keep up. Cyberlaw is the cyber-based legal dealings of any legal issues and actions that take place in the digital world. The reason why this is critically so important to consider is that if you become a victim of cybercrime, what is your recourse? Also, if you are thinking of committing a cybercrime, think again – the police, FBI, and other federal intelligence groups are keeping an eye open and are armed with evidence collection methods, laws, and safeguards to protect and serve the innocent.

Some of the most common issues that raise questions in the court of law is, how does the Internet fall into jurisdiction issues? What about privacy rights? In our attempts to answer these questions, we will review a cybercrime case to show how cyberlaw works and how those who fall victim can be protected and those who perpetrate crimes can be held accountable. In some cases, such as that of Alexis Pilkington (New York) who committed suicide allegedly from cyberbullying, the crimes perpetrated could lead to death.

Surveillance and Cybercrime Sample Law

In the next section, we will review a case where the United States and Erik Bowker had their day in court. On September 25, 2001, Bowker was charged with one count of interstate stalking, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2261A(1); one count of cyberstalking, in violation of 18U.S.C. § 2261A(2); one count of theft of mail, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1708; and one count of telephone harassment, in violation of 47 U.S.C. § 223(a)(1)(C). On June 6, 2002, a jury returned guilty verdicts on all charges. The government moved for an upward departure from the sentencing guidelines based on the victim’s extreme psychological harm. On September 10, 2002, the district court sentenced Bowker to 96 months incarceration, 3 years supervised release, and a $400 special assessment. In assessing the term of incarceration, the district court granted the government’s motion for an upward departure.

Count1 (interstate stalking)[1], Count 2 (cyberstalking)[2], and Count 4 (telephone harassment)[3] track the language of the relevant statutes. Count 1 alleges that between July 10 and July 30, 2001, Bowker knowingly and intentionally traveled across the Ohio state line with the intent to injure, harass, and intimidate Tina Knight, and as a result of such travel placed Knight in reasonable fear of death or serious bodily injury, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2261A(1). Count 2 alleges that between December 25, 2000 and August 18, 2001 Bowker, located in Ohio, knowingly and repeatedly used the Internet to engage in a course of conduct that intentionally placed Knight, then located in West Virginia, in reasonable fear of death or serious bodily injury, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2261A(2). Count 4 alleges that between June 12, 2001 and August 27, 2001, Bowker, located in Ohio, knowingly made telephone calls, whether or not conversation or communication ensued, without disclosing his identity and with the intent to annoy, abuse, threaten, and harass Knight, in violation of 47 U.S.C. § 223(a)(1)(C). Because the indictment stated all of the statutory elements of the offenses, and because the relevant statutes state the elements unambiguously, the district court properly denied Bowker’s motion to dismiss Counts 1, 2, and 4 of the indictment. The indictment’s reference to the specific dates and locations of the offenses, as well as the means used to carry them out (travel, Internet, telephone), provided Bowker fair notice of the conduct with which he was being charged.

We hold that the above-described facts amply justified the district court’s upward departure determination. Cf. United States v. Otto, 64 F.3d 367, 371 (8th Cir.1995) (affirming upward departure where stalking victim lived in constant fear for herself and for her children and was always on the lookout for the defendant; could not eat or sleep; lost weight; required counseling; and feared the defendant’s ultimate release); United States v. Miller, 993 F.2d 16, 21 (2d Cir.1993) (affirming upward departure after the defendant had engaged in a 3-year campaign of harassment; noting that the victim had been afraid to answer the telephone or open her mail for 3 years; was afraid to remain in the New York area; and believed that the years of harassment had hastened her husband’s demise).

Summary

In this chapter, we have discussed the fundamentals of digital surveillance, what reconnaissance is, and what digital spying is. While discussing the history of digital spying, we looked at how government entities, militaries, and others have been practicing for decades to gain tactical advantage and gather intelligence. While discussing these topics, we covered major legislature put in place to provide privacy to those under the fourth amendment as an example.

We flashed forward to today’s current events to discuss how the US-based NSA is under scrutiny for crossing boundaries it may or may not have been entitled to do and the whistleblower (Edward Snowden) who brought the issues to public eyes. We also examined why trust is so important when it comes to common surveillance activities that are supposed to keep you safe and secure such as traffic camera’s, home monitoring systems, and the government’s goal of stopping terrorism by collecting all incoming and outgoing data transmissions into and out of the country.

Those who spy and why they spy were also covered. We discussed experts in the field who help build legal cases, those who are in charge of our security, those who subvert it, and those who collect information for many reasons both good and bad.

Legal and ethical concerns were covered as well as sample case law to show the effects of digital surveillance from a legal perspective to just how important it is to not only protect ourselves but also be aware of the many dangers lurking in the digital darkness.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.