Homeland Security

Rahul Bhaskar, Ph.D. and Bhushan Kapoor, California State University

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, permanently changed the way the United States and the world’s other most developed countries perceived the threat from terrorism. Massive amounts of resources were mobilized in a very short time to counter the perceived and actual threats from terrorists and terrorist organizations. In the United States, this refocus was pushed as a necessity for what was called homeland security. The homeland security threats were anticipated for the IT infrastructure as well. It was expected that not only the IT at the federal level was vulnerable to disruptions due to terrorism-related attacks but, due to the ubiquity of the availability of IT, any organization was vulnerable. Soon after the terrorist attacks, the U.S. Congress passed various new laws and enhanced some existing ones that introduced sweeping changes to homeland security provisions and to the existing security organizations. The executive branch of the government also issued a series of Homeland Security Presidential Directives to maintain domestic security. These laws and directives are comprehensive and contain detailed provisions to make the U.S. secure from its vulnerabilities. Later in the chapter, we describe some principle provisions of these homeland security-related laws and presidential directives. Next, we discuss the organizational changes that were initiated to support homeland security in the United States. Then we highlight the 9-11 Commission that Congress charted to provide a full account of the circumstances surrounding the attacks and to develop recommendations for corrective measures that could be taken to prevent future acts of terrorism. We also detail the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 and the Implementing the 9-11 Commission Recommendations Act of 2007. Finally, we summarize the chapter’s discussion.

Keywords

homeland security; intelligence; terrorism; terrorist; terrorist attacks; statutory authorities; patriot act; aviation security; transportation security; border security

1 Statutory Authorities

Here we discuss the important homeland security-related laws passed in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. These laws are listed in Figure 7.1.

The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (PL 107-56)

Just 45 days after the September 11 attacks, Congress passed the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (also known as the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001). This Act, divided into 10 titles, expands law enforcement powers of the government and law enforcement authorities.1 These titles are listed in Figure 7.2. A summary of the titles is shown in the sidebar, “Summary of USA PATRIOT Act Titles.”

The Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001 (PL 107-71)

The series of September 11 attacks, perpetrated by 19 hijackers, killed 3000 people and brought commercial aviation to a standstill. It became obvious that enhanced laws and strong measures were needed to tighten aviation security. The Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001 transfers authority over civil aviation security from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA).2 With the passage of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, the TSA was later transferred to the Department of Homeland Security.

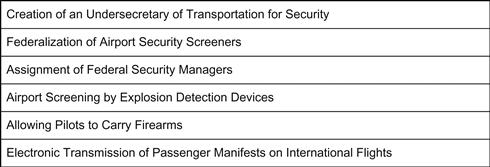

Key features of the act include the creation of an Undersecretary of Transportation for Security; federalization of airport security screeners; and the assignment of Federal Security Managers to each airport. Also included in the act are these provisions: airports provide for the screening of all checked baggage by explosive detection devices; allowing pilots to carry firearms; requiring the electronic transmission of passenger manifests on international flights prior to landing in the U.S.; requiring background checks, including national security checks, of persons who have access to secure areas at airports; and requiring that all federal security screeners be U.S. citizens.3 These key features are highlighted in the Figure 7.3.

Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act of 2002 (PL 107–173)

This Act, divided into six titles, represents the most comprehensive immigration-related response to the terrorist threat.4 The titles are listed in Figure 7.4. A summary of these titles is shown in the sidebar, “Summary of the Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act of 2002.”

Public Health Security, Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002 (PL 107–188)

The Act authorizes funding for a wide range of public health initiatives.5 Title I of the Act addresses the national need to combat threats to public health, and to provide grants to state and local governments to help them prepare for public health emergencies, including emergencies resulting from acts of bioterrorism. The Act establishes opportunities for grants and cooperative agreements for states and local governments to conduct evaluations of public health emergency preparedness, and enhance public health infrastructure and the capacity to prepare for and respond to those emergencies. Other grants support efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance, improve public health laboratory capacity, and support collaborative efforts to detect, diagnose, and respond to acts of bioterrorism. The Act also addresses other related public health security issues. Some of these provisions include:

• New controls on biological agents and toxins

• Additional safety and security measures affecting the nation’s food and drug supply

• Additional safety and security measures affecting the nation’s drinking water

• Measures affecting the Strategic National Stockpile and development of priority countermeasures to bioterrorism

Homeland Security Act of 2002 (PL 107-296)

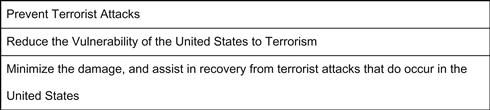

This landmark Act establishes a new Executive Branch agency, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and consolidates the operations of 22 existing federal agencies.6 The primary mission of the DHS is given in Figure 7.5. As a part of this act, a directorate (see checklist, “An Agenda For Action For Implementing The Directorate Of Information Analysis And Infrastructure Protection”) of information analysis and infrastructure protection was set up.

E-Government Act of 2002 (PL 107–347)

The E-Government Act of 2002 establishes a Federal Chief Information Officers Council to oversee government information and services, and creation of a new Office of Electronic Government within the Office of Management and Budget.8 The purposes of the Act are:

• To provide effective leadership of federal government efforts to develop and promote electronic government services and processes by establishing an Administrator of a new Office of Electronic Government within the Office of Management and Budget.

• To promote use of the Internet and other information technologies to provide increased opportunities for citizen participation in government.

• To promote interagency collaboration in providing electronic government services, where this collaboration would improve the service to citizens by integrating related functions, and in the use of internal electronic government processes, where this collaboration would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the processes.

• To improve the ability of the government to achieve agency missions and program performance goals.

• To promote the use of the Internet and emerging technologies within and across government agencies to provide citizen-centric government information and services.

• To reduce costs and burdens for businesses and other government entities.

• To promote better informed decision-making by policy makers.

• To promote access to high quality government information and services across multiple channels.

• To make the federal government more transparent and accountable.

• To transform agency operations by utilizing, where appropriate, best practices from public and private sector organizations.

• To provide enhanced access to government information and services in a manner consistent with laws regarding protection of personal privacy, national security, records retention, access for persons with disabilities, and other relevant laws.

Title III of the Act is known as the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002. This act applies to the national security systems, that include any information systems used by an agency or a contractor of an agency involved in intelligence activities; cryptology activities related to the nation’s security; command and control of military equipment that is an integral part of a weapon or weapons system or is critical to the direct fulfillment of military or intelligence missions. Nevertheless, this definition does not apply to a system that is used for routine administrative and business applications (including payroll, finance, logistics, and personnel management applications). The purposes of this Title are to:

• Provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of information security controls over information resources that support federal operations and assets.

• Recognize the highly networked nature of the current federal computing environment and provide effective government-wide management and oversight of the related information security risks, including coordination of information security efforts throughout the civilian, national security, and law-enforcement communities.

• Provide for development and maintenance of minimum controls required to protect federal information and information systems.

• Provide a mechanism for improved oversight of federal agency information security programs.

• Acknowledge that commercially developed information security products offer advanced, dynamic, robust, and effective information security solutions, reflecting market solutions for the protection of critical information infrastructures important to the national defense and economic security of the nation that are designed, built, and operated by the private sector.

• Recognize that the selection of specific technical hardware and software information security solutions should be left to individual agencies from among commercially developed products.

2 Homeland Security Presidential Directives

Presidential directives are issued by the National Security Council and are signed or authorized by the President. A series of Homeland Security Presidential Directives (HSPDs) were issued by President George W. Bush on matters pertaining to Homeland Security9:

• HSPD 1: Organization and Operation of the Homeland Security Council. Ensures coordination of all homeland security-related activities among executive departments and agencies and promotes the effective development and implementation of all homeland security policies.

• HSPD 2: Combating Terrorism Through Immigration Policies. Provides for the creation of a task force which will work aggressively to prevent aliens who engage in or support terrorist activity from entering the United States and to detain, prosecute, or deport any such aliens who are within the United States.

• HSPD 3: Homeland Security Advisory System. Establishes a comprehensive and effective means to disseminate information regarding the risk of terrorist acts to federal, state, and local authorities and to the American people.

• HSPD 4: National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction. Applies new technologies, increased emphasis on intelligence collection and analysis, strengthens alliance relationships, and establishes new partnerships with former adversaries to counter this threat in all of its dimensions.

• HSPD 5: Management of Domestic Incidents. Enhances the ability of the United States to manage domestic incidents by establishing a single, comprehensive national incident management system.

• HSPD 6: Integration and Use of Screening Information. Provides for the establishment of the Terrorist Threat Integration Center.

• HSPD 7: Critical Infrastructure Identification, Prioritization, and Protection. Establishes a national policy for federal departments and agencies to identify and prioritize United States critical infrastructure and key resources and to protect them from terrorist attacks.

• HSPD 8: National Preparedness. Identifies steps for improved coordination in response to incidents. This directive describes the way federal departments and agencies will prepare for such a response, including prevention activities during the early stages of a terrorism incident. This directive is a companion to HSPD-5.

• HSPD 8 Annex 1: National Planning. Further enhances the preparedness of the United States by formally establishing a standard and comprehensive approach to national planning.

• HSPD 9: Defense of United States Agriculture and Food. Establishes a national policy to defend the agriculture and food system against terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies.

• HSPD 10: Biodefense for the 21st Century. Provides a comprehensive framework for our nation’s Biodefense.

• HSPD 11: Comprehensive Terrorist-Related Screening Procedures. Implements a coordinated and comprehensive approach to terrorist-related screening that supports homeland security, at home and abroad. This directive builds upon HSPD 6.

• HSPD 12: Policy for a Common Identification Standard for Federal Employees and Contractors. Establishes a mandatory, government-wide standard for secure and reliable forms of identification issued by the federal government to its employees and contractors (including contractor employees).

• HSPD 13: Maritime Security Policy. Establishes policy guidelines to enhance national and homeland security by protecting U.S. maritime interests.

• HSPD 15: U.S. Strategy and Policy in the War on Terror.

• HSPD 16: Aviation Strategy. Details a strategic vision for aviation security while recognizing ongoing efforts, and directs the production of a National Strategy for Aviation Security and supporting plans.

• HSPD 17: Nuclear Materials Information Program.

• HSPD 18: Medical Countermeasures against Weapons of Mass Destruction. Establishes policy guidelines to draw upon the considerable potential of the scientific community in the public and private sectors to address medical countermeasure requirements relating to CBRN threats.

• HSPD 19: Combating Terrorist Use of Explosives in the United States. Establishes a national policy, and calls for the development of a national strategy and implementation plan, on the prevention and detection of, protection against, and response to terrorist use of explosives in the United States.

• HSPD 20: National Continuity Policy. Establishes a comprehensive national policy on the continuity of federal government structures and operations and a single National Continuity Coordinator responsible for coordinating the development and implementation of federal continuity policies.

• HSPD 20 Annex A: Continuity Planning. Assigns executive departments and agencies to a category commensurate with their COOP/COG/ECG responsibilities during an emergency.

• HSPD 21: Public Health and Medical Preparedness. Establishes a national strategy that will enable a level of public health and medical preparedness sufficient to address a range of possible disasters.

• HSPD 23: National Cyber Security Initiative.

• HSPD 24: Biometrics for Identification and Screening to Enhance National Security. Establishes a framework to ensure that federal executive departments use mutually compatible methods and procedures regarding biometric information of individuals, while respecting their information privacy and other legal rights.

3 Organizational Actions

These laws and homeland security presidential directives called for deep and fundamental organizational changes to the executive branch of the government. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 established a new Executive Branch agency, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and consolidated the operations of 22 existing federal agencies.10 This Department’s overriding and urgent missions are (1) to lead the unified national effort to secure the country and preserve our freedoms, and (2) to prepare for and respond to all hazards and disasters. The citizens of the United States must have the utmost confidence that the Department can execute both of these missions.

Faced with the challenge of strengthening the components to function as a unified Department, DHS must coordinate centralized, integrated activities across components that are distinct in their missions and operations. Thus, sound and cohesive management is the key to department-wide and component-level strategic goals. We seek to harmonize our efforts as we work diligently to accomplish our mission each and every day.

The Department of Homeland Security is headed by the Secretary of Homeland Security. It has various departments, including management, science and technology, health affairs, intelligence and analysis, citizenship and immigration services, and national cyber security center.

Department of Homeland Security Subcomponents

There are various subcomponents of The Department of Homeland Security that are involved with Information Technology Security.11 These include the following:

• The Office of Intelligence and Analysis is responsible for using information and intelligence from multiple sources to identify and assess current and future threats to the United States.

• The National Protection and Programs Directorate houses offices of the Cyber Security and Communications Department.

• The Directorate of Science and Technology is responsible for research and development of various technologies, including information technology.

• The Directorate for Management is responsible for department budgets and appropriations, expenditure of funds, accounting and finance, procurement, human resources, information technology systems, facilities and equipment, and the identification and tracking of performance measurements.

• The Office of Operations Coordination works to deter, detect, and prevent terrorist acts by coordinating the work of federal, state, territorial, tribal, local, and private-sector parties and by collecting and turning information from a variety of sources. It oversees the Homeland Security Operations Center (HSOC), which collects and fuses information from more than 35 federal, state, local, tribal, territorial, and private-sector agencies.

State and Federal Organizations

There are various organizations that support information sharing at the state and the federal levels. The Department of Homeland Security through the Office of Intelligence and Analysis provides personnel with operational and intelligence skills. The support to the state agencies is tailored to the unique needs of the locality and serves to:

• Help the classified and unclassified information flow

As of March 2008, there were 58 fusion centers around the country. The Department has provided more than $254 million from FY 2004–2007 to state and local governments to support the centers.

The Homeland Security Data Network (HSDN), which allows the federal government to move information and intelligence to the states at the Secret level, is deployed at 19 fusion centers. Through HSDN, fusion center staff can access the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), a classified portal of the most current terrorism-related information.

There are various organizations at the state levels that support the homeland security initiatives. These organizations vary in their size and budget from very large independently run departments to a department that is a part of a larger related department. As an example, California has the Office of Management Services that is responsible for any emergencies in the state of California. The Governor’s Office of Homeland Security is responsible for the coordination among different departments to secure the state against potential terrorist threats. Very specific to IT security, the California Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection is functional.

The Governor’s Office of Homeland Security

The Governor’s Office of Homeland Security (OHS) acts as the Cabinet-level state office for the prevention of and preparation for a potential terrorist event.12 OHS serves a diverse set of federal, state, local, private sector, and tribal entities by taking an “all-hazards” approach to reducing risk and increasing responder capabilities.

Because California is prone to floods, fires, and earthquakes in addition to the potential for an attack using manmade weapons of mass destruction, OHS is committed to contributing to a comprehensive, well-planned all-hazards strategy to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from any possible emergency. OHS is responsible for several key state functions, including13:

California Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection

The California Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection (OISPP) unites consumer privacy protection with the oversight of government’s responsible management of information. OISPP provides services to consumers, recommends practices to business, and provides policy direction, guidance, and compliance monitoring to state government.14

OISPP was established within the State and Consumer Services Agency by Chapter 183 of the Statutes of 2007 (Senate Bill 90), effective January 1, 2008. This legislation merged the Office of Privacy Protection, which opened in 2001 in the Department of Consumer Affairs with a mission of identifying consumer problems in the privacy area and encouraging the development of fair information practices, and the State Information Security Office, established within the Department of Finance with a mission of overseeing information security, risk management, and operational recovery planning within state government.15

Private Sector Organizations for Information Sharing

Intelligence sharing and analysis groups have been set up in many private infrastructure industries. As an example, National Electric Reliability Council has such a group, Electricity Sector Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ESISAC), which serves the electricity sector by facilitating communications between sector participants, federal governments, and other critical infrastructure organizations. It is the job of the ESISAC to promptly disseminate threat indications, analyses, and warnings, together with interpretations, to assist electricity sector participants take protective actions. Similarly, many other organizations in other infrastructure sectors are also members of an ISAC.

There are other organizations that share information among the member companies on issues related to incident response (see sidebar, “National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States [The 9-11 Commission]”). These organizations include FIRST, the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams,16 which has as its members major corporations from all over the world. The FBI encourages organizations from the private sector to become members of InfraGard to encourage exchange of information among the members.17

4 Summary

Within about a year after the terrorist attacks, Congress passed various new laws, such as The USA PATRIOT Act, Aviation and Transportation Security Act, Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act, Public Health Security, Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act, Homeland Security Act, and E-Government Act, and introduced sweeping changes to homeland security provisions and to the existing security organizations. The executive branch of the government also issued a series of Homeland Security Presidential Directives (HSPDs) to maintain domestic security. These laws and directives are comprehensive and contain detailed provisions to make the United States secure. For example, HSPD 5 enhances the ability of the United States to manage domestic incidents by establishing a single, comprehensive national incident management system.

These laws and homeland security presidential directives call for deep and fundamental organizational changes to the executive branch of the government. For example, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 established a new Executive Branch agency, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and consolidated the operations of 22 existing federal agencies. Intelligence-sharing and analysis groups have been set up in many private infrastructure industries as well. For example, the National Electric Reliability Council has such a group, the Electricity Sector Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ESISAC), which serves the electricity sector by facilitating communications between sector participants, federal governments, and other critical infrastructure organizations.

Congress charted the “National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (The 9-11 Commission)” on November 27, 2002, to provide a “full and complete accounting” of the attacks of September 11, 2001, and recommendations as to how to prevent such attacks in the future. On July 22, 2004, the 9-11 Commission issued its final report, which included 41 wide-ranging recommendations to help prevent future terrorist attacks. Many of these recommendations were put in place with the passage of the “Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act” and “Implementing Recommendations of the 9-11 Commission Act of 2007.”

About a year after the passing of this law, the Majority Staffs of the Committees on Homeland and Foreign Affairs drew its attention on the extent to which the law was indeed implemented and issued a report on “Wasted Lessons of 9/11: How the Bush Administration Ignored the Law and Squandered Its Opportunities to Make Our Country Safer.” This report demonstrates that it is clear that the Bush Administration did not deliver on myriad critical homeland and national security mandates set forth in the “Implementing the 9-11 Commission Recommendations Act of 2007.” Fulfilling the unfinished business of the 9-11 Commission will most certainly be a major focus of President Obama, as many of the statutory requirements are to be met in stages.

Finally, let’s move on to the real interactive part of this Chapter: review questions/exercises, hands-on projects, case projects and optional team case project. The answers and/or solutions by chapter can be found in the Online Instructor’s Solutions Manual.

Chapter Review Questions/Exercises

True/False

1. True or False? The Public Health Security, Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002, authorizes funding for a wide range of public health initiatives.

2. True or False? The Homeland Security Act of 2002 establishes a new Executive Branch agency, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and consolidates the operations of 33 existing federal agencies.

3. True or False? The E-Government Act of 2012 establishes a Federal Chief Information Officers Council to oversee government information and services, and creation of a new Office of Electronic Government within the Office of Management and Budget.

4. True or False? Presidential directives are issued by the National Security Council and are signed or authorized by the Vice President.

5. True or False? The homeland security presidential directives called for deep and fundamental organizational changes to the executive branch of the government.

Multiple Choice

1. Faced with the challenge of strengthening the components to function as a unified Department, ________________ must coordinate centralized, integrated activities across components that are distinct in their missions and operations.

2. There are various ____________ of The Department of Homeland Security that are involved with Information Technology Security.

A. Network attached storage (NAS)

3. There are various ___________that support information sharing at the state and the federal levels.

4. The Governor’s Office of Homeland Security (OHS) acts as the ___________ for the prevention of and preparation for a potential terrorist event.

5. The California Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection (OISPP) unites _________ with the oversight of government’s responsible management of information.

Exercise

Problem

How does the new National Terrorism Advisory System (NTAS) work?

Hands-on Projects

Project

How will one find out that an NTAS Alert has been announced?

Case Projects

Problem

What should Americans do when an NTAS Alert is announced?

Optional Team Case Project

Problem

How should one report suspicious activity?

1“USA PATRIOT Act of 2001” U.S. Government Printing Office, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ056.107.pdf (downloaded 10/20/2008).

2“Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001,” National Transportation Library, http://ntl.bts.gov/faq/avtsa.html (downloaded 10/20/2008).

3“Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001,” National Transportation Library, http://ntl.bts.gov/faq/avtsa.html (downloaded 10/20/2008).

4“Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act of 2002 (PL 107-173),” Center for Immigration Studies, www.cis.org/articles/2002/back502.html (downloaded 10/20/2008).

5“Public Health Security, Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002,” U.S. Government Printing Office, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publl88.107 (downloaded 10/20/2008).

6“Homeland Security Act of 2002,” Homeland Security, www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/law_regulation_rule_0011.shtm (downloaded 10/20/2008).

7“Homeland Security Act of 2002,” Homeland Security, www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/law_regulation_rule_0011.shtm (downloaded 10/20/2008).

8“E-Government Act of 2002,” U.S. Government Printing Office, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ347.107.pdf (downloaded 10/20/2008).

9“Homeland Security presidential directives,” Homeland Security, https://www.drii.org/professional_prac/profprac_appendix.html#BUSINESS_CONTINUITY_PLANNING_INFORMATION, 2008 (downloaded 10/24/2008).

10“Public Health Security, Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002,” U.S. Government Printing Office, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ188.107 (downloaded 10/20/2008).

11“Public Health Security, Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002,” U.S. Government Printing Office, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ188.107 (downloaded 10/20/2008).

12“The Governor’s Office of Homeland Security (OHS),” www.homeland.ca.gov/(downloaded 10/24/2008).

13“The Governor’s Office of Homeland Security (OHS),” www.homeland.ca.gov/ (downloaded 10/24/2008).

14“California Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection,” www.oispp.ca.gov/ (downloaded 10/20/2008).

15“California Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection,” www.oispp.ca.gov/ (downloaded 10/20/2008).

16“Forum of incident response and security teams,” www.first.org/ downloaded 10/20/2008).

17InfraGard, www.infragard.net/ (downloaded 10/20/2008).