Chapter 3. Crisis Management

On September 7, 2017, Equifax, one of the “big three” consumer credit reporting agencies, announced a massive data breach affecting 143 million U.S. consumers—almost half the population of the entire United States. By the time the dust had settled, the company announced that 146.6 million U.S. consumers were impacted, as well as approximately 15 million U.K. citizens and 19,000 Canadians.1

1. Equifax, “Equifax Announces Cybersecurity Incident Involving Consumer Information,” Equifax Announcements, September 7, 2017, https://www.equifaxsecurity2017.com/2017/09/07/equifax-announces-cybersecurity-incident-involving-consumer-information.

According to Equifax’s press release, “[T]he information accessed primarily includes names, Social Security numbers (SSNs), birth dates, addresses and, in some instances, driver’s license numbers. In addition, credit card numbers for approximately 209,000 U.S. consumers, and certain dispute documents with personal identifying information for approximately 182,000 U.S. consumers, were accessed.”2

2. Equifax, “Equifax Announces Cybersecurity Incident.”

Nearly half of all SSNs had been exposed in one fell swoop. “This is about as bad as it gets,” said Pamela Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum. “If you have a credit report, chances are you may be in this breach. The chances are much better than 50 percent.”3

3. T. Siegel Bernard, T. Hsu, N. Perlath, and R. Lieber, “Equifax Says Cyberattack May Have Affected 143 Million in the U.S.,” New York Times, September 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/business/equifax-cyberattack.html.

Equifax had quietly spent six weeks investigating its breach and had the luxury of planning its own disclosure. In preparation for the public announcement, it had:

Put together a polished press release.

Retained cybersecurity attorneys from the firm King & Spalding LLP.

Hired the forensics firm Mandiant to investigate.

Reported the incident to the FBI.

Set up a website, www.equifaxsecurity2017.com, which (in theory) allowed consumers to check whether they were affected and to register for the remedial package if so.

Set up call centers to assist consumers. According to Chief Executive Officer Rick Smith, this involved hiring and training thousands of customer service representatives in less than two weeks.

Developed a “robust package of remedial materials,” which, according to Smith, included “(1) monitoring of consumer credit files across all three bureaus, (2) access to Equifax credit files, (3) the ability to lock the Equifax credit file, (4) an insurance policy to cover out-of-pocket costs associated with identity theft, and (5) dark web scans for consumers’ social security numbers.”4

4. Hearing on “Oversight of Equifax Data Breach: Answers for Consumers” Before the Subcomm. on Digital Commerce and Consumer Protection of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 115th Cong. (October 3, 2017), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF17/20171003/106455/HHRG-115-IF17-Wstate-SmithR-20171003.pdf (prepared testimony of Richard F. Smith, former Chairman and CEO, Equifax).

It looked good on paper—but it all went terribly wrong.

Immediately following the breach notification, Equifax’s stock prices took a nosedive. Shortly thereafter, the chief information officer (CIO) and chief security officer (CSO) resigned. Within a few weeks, CEO Rick Smith would resign as well (although he was later called to testify before Congress, where his statements fueled public outrage).

Within two months of the breach, Equifax was facing more than 240 consumer class-action lawsuits, as well as lawsuits filed by financial institutions and shareholders. The company reported in its quarterly SEC 10-Q filing that it was “cooperating with federal, state, city and foreign governmental agencies and officials investigating or otherwise seeking information and/or documents . . . including 50 state attorneys general offices, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB), the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the New York Department of Financial Services, as well as other regulatory agencies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.5

5. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), “Equifax Inc.,” Form 10-Q, 2017, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/33185/000003318517000032/efx10q20170930; Hayley Tsukayama, “Equifax Faces Hundreds of Class-Action Lawsuits and an SEC Subpoena over the Way It Handled Its Data Breach,” Washington Post, November 9, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2017/11/09/equifax-faces-hundreds-of-class-action-lawsuits-and-an-sec-subpoena-over-the-way-it-handled-its-data-breach.

By the time Equifax released its first-quarter report for 2018, the company had spent $242.7 million in response to the breach. In July 2019, Equifax agreed to pay up to $700 million as part of a settlement with the FTC, the CFPB, and 50 U.S. states and territories.

The breach shone a spotlight on the “underregulated” data brokerage industry. A flurry of new legislation was proposed in Congress, such as bills to support national data breach notification, credit report error correction, and even the “Freedom from Equifax Exploitation (FREE) Act,” which would give consumers more control over credit report freezes and fraud alerts. There was even a proposed “Data Broker Accountability and Transparency Act,” which would “press data broker companies, including recently breached credit report company Equifax, to implement better privacy and security practices.”6

6. Joe Uchill, “Dems Propose Data Security Bill after Equifax Hack,” Hill, September 14, 2017, http://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/350694-on-heels-of-equifax-breach-dems-propose-data-broker-privacy-and-security.

“Equifax will not be defined by this incident, but rather, by how we respond,” said CEO Rick Smith valiantly, on the day the breach was announced. It was true. While the Equifax breach itself was bad, what turned it into an utter disaster was the company’s response, as we will see. In its immediate response to the breach, Equifax made choices that destroyed the public’s trust by undermining the perception of its competence, character, and caring. This led to a reckoning not just for Equifax but for the data brokerage industry as a whole.

3.1 Crisis and Opportunity

According to crisis management expert Steven Fink:7

7. Steven Fink, Crisis Communications: The Definitive Guide to Managing the Message (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013), xv.

A crisis is a fluid and dynamic state of affairs containing equal parts danger and opportunity. It is a turning point, for better or worse. The Chinese have a word for this: wei-fi.

As any experienced cybersecurity professional will tell you, most data breaches are “a fluid and dynamic state of affairs” (which is part of why is it so challenging to plan your response ahead of time). Every data breach (or suspected data breach) involves inherent danger. There is, of course, the obvious risk that a criminal will acquire and misuse sensitive information. There is the risk of outrage and loss of goodwill of customers, shareholders, and employees. There is the danger of lawsuits and fines. There is the risk of symbolic and unnecessary firings or reorganizations that damage morale and business operations. There is potential for direct financial, reputational, and operational damage.

And yet, data breaches can present enormous opportunities. When you are caught in the midst of a crisis, it can be hard to focus on the positive, but doing so can reap rewards. Data breaches happen for a reason (in fact, like car accidents, they are usually the result of multiple failures). In response to a data breach, we have seen organizations suddenly engage customers, employees, and shareholders more effectively than ever before, taking great pains to listen, understand, and react. Data breaches can quickly oust ineffective leaders and spur much-needed management changes. They can inspire management to appropriately prioritize and invest in modern computer technology, which increases both security and efficiency. They can be catalysts that propel organizations and even whole industries to become stronger in the long run: more secure, more organized, and more effective communicators.

The outcome of a crisis depends on how you react. Unfortunately, relatively few organizations plan for data breaches as a potential crisis, and therefore don’t have the necessary resources in place to effectively manage data breaches that escalate to this level. Much like organizations that handle hazardous waste, any organization that stores, processes, or transmits a significant volume of sensitive data should be prepared to handle a data breach crisis.

3.1.1 Incidents

Today, the majority of organizations that plan for data breaches include it as part of their cybersecurity incident response program, which is typically developed within the IT department. This is largely for historical reasons and not because it is the best strategy. In the early 2000s, virulent worms such as Blaster, Slammer, and MyDoom wreaked havoc across networks, infecting hundreds of thousands of computers and causing network outages. Information security teams prepared by implementing antivirus, network monitoring, intrusion detection, patching, and reimaging mechanisms. It was clear that the community needed a model for planning and responding to these types of threats.

In January 2004, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released its first Computer Security Incident Handling Guide. What is an “incident”? According to NIST: “A computer security incident is a violation or imminent threat of violation of computer security policies, acceptable use policies, or standard security practices.”8

8. Paul R. Cichonski, Thomas Millar, Timothy Grance, and Karen Scarfone, Computer Security Incident Handling Guide, Special Pub. 800-61, rev. 2 (Washington, DC: NIST, 2012), https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-61r2.pdf.

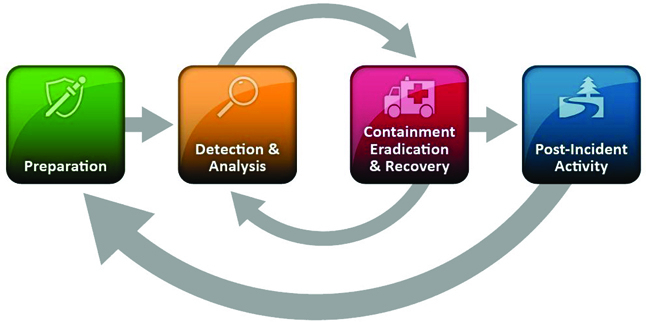

The classic NIST model breaks a cyclical incident response process into four high-level phases, shown in Figure 3-1:

Preparation

Detection and Analysis

Containment, Eradication, and Recovery

Post-Incident Activity

Theoretically, responders move through these phases of response in roughly linear cycle, returning to previous phases repeatedly as needed.

The NIST incident response lifecycle model actually worked very well when applied to the most widespread cybersecurity incidents of the early 2000s. When a virus or worm was detected, it was analyzed and then “contained” using network throttling or antivirus. The infected system was cleaned or reimaged (“eradication”); data was restored (“recovery”); and finally the incident was documented and (if necessary) discussed at a postmortem meeting.

Since then, organizations throughout the nation have used it as the basis for planning and managing cybersecurity incident response, including data breaches. And therein lies the problem: While the NIST guide is very helpful for managing many kinds of computer security incidents, as we will see, a data breach is typically not just an incident and therefore must be managed differently.

3.1.2 Data Breaches Are Different

Where in the NIST incident response lifecycle is the part where regulators fine your organization for negligence? Where does the CEO make a public statement? Where are the notification letters, the phone calls to insurers, the class-action lawsuits?

The NIST model can supposedly apply to “loss of data confidentiality,” but frankly, the tidy NIST model isn’t all that useful when managing a data breach. Most organizations include data breaches in cybersecurity incident response plans, but when an actual data breach occurs, the playbook goes out the window.

3.1.3 Recognizing Crises

Crisis management expert Ian Mitroff carefully differentiates between an incident and a crisis as follows:

An incident is “a disruption of a component, a unit, or a subsystem of a larger system, such as a valve or a system generator in a nuclear plant. The operation of the whole system is not threatened and the defective part is merely repaired.”

A crisis is “a disruption that . . . affects a system as a whole.”9

9. T. Pauchant and I. Mitroff, Transforming the Crisis-Prone Organization (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992), 12.

Steven Fink further defines a crisis as “any prodromal situation that runs the risk of”:

Escalating in intensity.

Falling under close media or government scrutiny.

Interfering with the normal operations of business.

Jeopardizing the positive public image presently enjoyed by a company or its officers.

Damaging a company’s bottom line in any way.10

10. Steven Fink, Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable, rev. ed. (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 1986), 23–24.

Data breaches, by their very nature, create risks in all five of Fink’s categories above.

3.1.4 The Four Stages of a Crisis

The NIST incident response lifecycle is very useful for certain types of incidents. However, the purpose of having a model is to help us to better understand a situation and respond more effectively. When it comes to data breaches, Fink’s crisis management model is a more useful tool for understanding data breach management and response, as we will see throughout this book.

According to Fink, every crisis moves through four stages. These stages are:11

11. Fink, Crisis Communications, 46.

Prodromal - The “precrisis” phase, in which there are warnings or precursors that, if acted upon, can enable responders to minimize the impact of the crisis.

Acute - The “time when chaos reigns supreme,” according to Fink. At this stage, the crisis has become visible outside the organization, and leadership must address it.

Chronic - During this stage, “litigation occurs, media exposes are aired, internal investigations are launched, government oversight investigations commence.” As the name implies, the chronic stage can last for years.

Resolution - The crisis is settled and normal activities resume.

These stages apply neatly to data breaches, which typically do include a prodrome (such as an intrusion detection system alert), followed by an acute phase (such as an intense media scandal). This results in lawsuits, public outcry, internal investigations, etc., as described in the chronic phase. Finally, the breached organization may reach the resolution stage, typically after undergoing changes to processes and procedures. It can take years to get there.

The goal of crisis management is to “manage the prodrome so successfully that you go from prodrome to resolution without falling into the morass of the acute and chronic stages.”12 The same is true of data breaches: the best way to manage a data breach is to prevent it from occurring in the first place. If that is not possible, the next best technique is to rely upon a strong detection and response program, so that your response team can identify the earliest signs of an intrusion and react quickly enough to minimize the risk of data exposure. Effective network instrumentation, logging, and alerting are key elements of a strong detection and response program. Finally, if a data breach reaches the acute crisis phase, then it is important to have a strong crisis management and crisis communications program in place. This latter piece—crisis communications—is critical. It is not enough to manage the data breach crisis itself; you must also take care to manage the perception of the crisis.

12. Fink, Crisis Communications, 47.

3.2 Crisis Communications, or Communications Crisis?

When planning for data breaches, many organizations emphasize the technical aspects of the response effort: modifying firewall rules on the fly, cleaning spyware and rootkits off endpoint systems, preserving evidence. This is part of the organization’s crisis management strategy, which addresses the “reality of the crisis.”13

13. Fink, Crisis Communications, 8.

If there is one area that is overlooked more than any other in data breach planning, it is crisis communications. Time and time again, we see organizations turn data breaches into reputational catastrophes due to classic communications mistakes.

“Crisis communications is managing the perception of that same reality,” explains Fink. “It is telling the public what is going on (or what you want the public to know about what is going on). It is shaping public opinion.”14 In a data breach crisis, a poor or nonexistent communications strategy can cause far more long-lasting damage than any actual harm caused by the breach itself. While a full exploration of effective crisis communications is outside the scope of this book, we will point out clear communications mistakes in the data breaches we study and share commonly accepted “rules of thumb” that can help your crisis communications go more smoothly.

14. Fink, Crisis Communications, 8.

When a data breach occurs, communications with key stakeholders such as customers, employees, shareholders, and the media are often developed on the fly. Sometimes multiple staff members talk to the press, leading to mixed messages. Other times, the organization goes radio silent, and the public is left with no answers, no reassurance, and a sense of distrust. In the next sections, we will break down why crisis communication is so important and provide reader with clear strategies for a strong response.

3.2.1 Image Is Everything

When a data breach crisis occurs, organizations face a significant threat to their image. “Image” is the perception of an organization in the mind of a stakeholder. Far from being a superficial matter, an organization’s image is vital.

A damaged image can impact customer relations, as well as investor confidence and stock values. Image is also critical for defining the organization’s relationship with law enforcement, regulators, and legislators. In a data breach, damage to an organization’s image can trigger consumer lawsuits, cause increased fines and settlement costs, and even affect the content of laws that are passed as a result of the crisis. It can impact hiring, morale, and employee retention. If image repair is fumbled, key executives may be forced to step down as a result of a breach, as Equifax’s CEO shockingly discovered.

The impact of a data breach on an organization’s image depends on many factors. Image repair expert William L. Benoit says that a threat to one’s image occurs when the relevant audience believes that:15

15. William L. Benoit, Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies, 2nd ed. (Albany: SUNY Press, 2014), 28.

An act occurred that is undesirable.

You are responsible for that action.

Data breaches can damage the relationship between stakeholders and the organization. There is a risk that the organization will be perceived as responsible for the undesirable act (the breach). This, in turn, creates a threat to the organization’s image.

3.2.2 Stakeholders

Fundamentally, a corporate image is the result of a relationship that the organization develops with each stakeholder. To use Equifax as an example, key stakeholders include:

Consumers

Shareholders

Employees

Regulators

Board of Directors

Legislators

And more

These categories of stakeholders have different concerns in the wake of a breach.

3.2.3 The 3 C’s of Trust

A data breach can injure the relationship between stakeholders and the organization. Specifically, it damages trust. Military psychologist Patrick J. Sweeney conducted a study of enlisted soldiers in 2003 and found that three factors were central to trust:16

16. Michael D. Matthews, “The 3 C’s of Trust,” Psychology Today, May 3, 2016, https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/head-strong/201605/the-3-c-s-trust.

Competence - Capable of skillfully executing one’s job

Character - Strong adherence to good values, including loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage

Caring - Genuine concern for the well-being of others

As we will see, these three factors apply as well in the context of trust between stakeholders and an organization.

3.2.4 Image Repair Strategies

Throughout this book, we will see that breached organizations work hard to preserve and repair their images. Here, we will introduce a model for analyzing different strategies, in order to evaluate their effectiveness.

Benoit lists five categories of image repair strategies:17

17. Benoit, Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies, 28.

Denial - The accused denies that the negative event happened or that he or she caused it.

Evasion of Responsibility - The accused attempts to avoid responsibility, such as by claiming the event was an uncontrollable accident or that he or she did not have the information or ability to control the situation.

Reducing Offensiveness - The accused attempts to reduce the audience’s negative feelings through one of six variants:

Bolstering - Highlighting positive actions and attributes of the accused

Minimization - Convincing the audience that the negative event was not as bad as it appears

Differentiation - Emphasizing differences between the event and similar negative occurrences

Transcendence - Placing the event in a different context

Attacking one’s accuser - Discrediting the source of accusations

Compensation - Offering remuneration in the form of valued goods and services

Corrective Action - The accused makes changes to repair damage and/or prevent similar situations from occurring in the future.

Mortification - The accused admits that he or she was wrong and asks for forgiveness.

All of these image repair strategies can, and have, been employed in data breach responses, some to greater effect than others.

3.2.5 Notification

Notification is perhaps the most critical part of data breach crisis communications, and it can have an enormous impact on public perception and image management. Key questions include:

When should you notify key stakeholders? Rarely, if ever, are all the facts about a data breach known up front. On the one hand, a quick notification can signal that you care and are acting in good faith. On the other hand, it may be the case that by waiting, you find out more information that reduces the scope of the notification requirements. There is no “right” time, and crisis management teams have many tradeoffs to consider.

Who should be notified? There are internal notifications (e.g., upper management, legal) In some cases, it may be appropriate to bring in law enforcement. Certain states require notification to an attorney general or other parties. Depending on the type of data exposed, it may be necessary to alert consumers or employees.

How should you notify? Paper mailings, email notification, a web announcement, or phone calls are all common options. Your notification requirements vary depending on the type of data exposed, the number of data subjects affected, the geographic location of the data subjects, and other factors. Notification can be expensive, and often cost is a limiting factor. Today, many organizations take a multipronged approach, which includes email or paper individual notifications, supported by a website FAQ and a call center where consumers can get more information.

What information should be included in a notification? On the one hand, you want to build trust and appear transparent. It’s also important to give data subjects enough information to reduce their risk, whenever that is possible. At the same time, current laws are not in line with the public’s expectations of privacy. Typically information that is not specifically regulated (such as shoppers’ purchase histories or web surfing habits) are not explicitly mentioned in data breach announcements, even if it is likely that information has been exposed.

In this section, we highlight some of the key challenges that breach response teams face when determining when, who, and how to notify.

3.2.5.1 Regulated vs. Unregulated Data

Data breach investigations are typically conducted to evaluate the risk that data regulated by a breach notification law or contractual clause was inappropriately accessed or acquired. Modern breach response teams are often led by an experienced attorney who acts as the “breach coach,” guiding the investigation and coordinating the participants. Digital forensic investigators take direction from the attorney, gathering and analyzing the evidence that the attorney needs to determine whether a notification statute or clause has been triggered.

Data breach notification laws emerged in the United States during a simpler time. Many state laws were created in response to the 2005 ChoicePoint breach (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, “Managing DRAMA”), when financial fraud had captured the media’s attention. Credit monitoring and identity theft protection emerged during this period as well and became a part of the cookie-cutter breach response process.

State breach notification laws do not require organizations to make a full confession to consumers, detailing every single data element that may have been stolen. Rather, the laws are designed to protect a specific, limited subset of “personal information.” Recall from Chapter 1 that most of the time, “personal information” includes:18

18. Baker Hostetler, “Data Breach Charts,” Baker Law, November 2017, https://www.bakerlaw.com/files/Uploads/Documents/Data%20Breach%20documents/Data_Breach_Charts.pdf.

[a]n individual’s first name or first initial and last name plus one or more of the following data elements: (i) Social Security number, (ii) driver’s license number or state- issued ID card number, (iii) account number, credit card number or debit card number combined with any security code, access code, PIN or password needed to access an account.

What about web surfing history, purchase history, “lifestyle interests,” salary information, and more? “As long as it doesn’t contain any of the data elements that would trigger notification such as Social Security Number or financial account information, then no, it would not trigger a notification obligation,” says data breach attorney and certified computer forensic examiner M. Scott Koller, of Baker Hostetler. Even in cases where regulated data elements are involved, breached organizations are not required to notify subjects about other, nonregulated elements that may have been accessed. “In my practice, I generally will include additional information so [affected persons] have a better sense of what occurred,” says Koller. “For example, if a real estate agent was breached, I would say that the information includes name, address, Social Security Number, and other information submitted with your application.” Koller cites mailing address as a common piece of information that may not be protected by statute but is often included in notification letters.

3.2.5.2 Left Out

Digital forensic analysis is often a painstaking, time-intensive, and expensive process. Reconstructing a picture of precisely what data elements were accessed, and when, can involve hundreds if not thousands of hours of labor, particularly if the organization did not retain good logs. Even breached organizations have limited budgets (and so do their insurers, who may be footing the bill). And again, there is the time pressure that comes from crisis communications needs.

As a result, data breach investigations often do not include the full range of an attacker’s activities. Rather, investigations normally focus on the regulated data elements and leave out systems that are not needed for complying with data breach notification requirements. Computers that don’t contain regulated data elements may not be included in digital evidence preservation at all.

For example, at Equifax, intruders reportedly first gained access to personal information in May 2017, after exploiting a vulnerability in a public-facing Equifax web server. Once the attackers gained a foothold, they explored the company’s internal network. They crawled through the network for more than two months before they were finally discovered on July 29. Bloomberg Technology later published an investigative report that revealed that criminals “had time to customize their tools to more efficiently exploit Equifax’s software, and to query and analyze dozens of databases to decide which held the most valuable data. The trove they collected was so large it had to be broken up into smaller pieces to try to avoid tripping alarms as data slipped from the company’s grasp through the summer.”19

19. Michael Riley, Jordan Robertson, and Anita Sharpe, “The Equifax Hack Has the Hallmarks of State-Sponsored Pros,” Bloomberg, September 29, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-09-29/the-equifax-hack-hasall-the-hallmarks-of-state-sponsored-pros.

Unregulated data such as web surfing activity, shopping history, or social connections may be stolen by an attacker, but data brokers would not be required to report that to the public, or even check to see whether anything was stolen in the first place. Equifax likely held extensive volumes of this type of data because it offers digital marketing services, including “Data-driven Digital Targeting” designed to track consumers and target advertisements. Exactly which Equifax databases did the attackers access? The public will likely never know. Equifax, like other data brokers, has amassed troves of sensitive consumer and business data, but only a small percentage is regulated by state and federal data breach notification laws.

Attorneys, forensics firms, the media, and the public are all focused on the potential exposure of SSNs and the risk of identity theft, just as they were a decade ago—but it is increasingly clear that technology and data analytics have changed the game. “There’s a trend toward expanding what qualifies as ‘personal information,’ and that trend has continued year after year,” says Koller. “So far, expansion is where people are sensitive . . . people are sensitive to medical information, sensitive to biometric information, usernames and passwords, because there’s harm to that.” In the coming years, data breach responders will need to stay up-to-date on the changing regulatory requirements, as well as key stakeholders’ (often unspoken) expectations.

3.2.5.3 Overnotification

Overnotification is when an organization alerts people to a potential data breach when it was not truly necessary. Since a data breach can cause reputational, financial, and operational damage, obviously overnotification is something to avoid. When it occurs, it is usually due to lack of evidence or easy access to log data.

Think of all the “megabreaches” you’ve read about in the news. Headlines announce that hundreds of thousands of patient records or millions of credit card numbers were exposed. Behind the scenes, there is often no proof that hackers actually acquired all of that data. Instead, the organization simply wasn’t logging access to sensitive information, and as a result there was no way for investigators to tell what data had actually been acquired and what remained untouched. Absent evidence, some regulations require organizations to assume that a breach occurred.

Today, cheap and widely available tools exist that will create a record of activities, such as every time a file is uploaded (or downloaded), every time a user logs in (or out), or every time a user views customer records. These log files can be absolutely invaluable in the event of a suspected breach.

Imagine that you are faced with a case where a hacker broke into a database server that housed 50,000 customer records. Upon reviewing the log files, your investigative team finds that only three customer records were actually accessed by the criminal. Intead of sending out 50,000 customer notifications, you send out three. Worth it? Definitely!

Every organization’s logging and monitoring system is unique and should be tailored to protect its most sensitive information assets. This reduces the risk of overnotification and can save an organization from a full-scale disaster.

3.2.5.4 Delays in Notification

Breach response teams are under enormous pressure to decide who needs to be notified as quickly as possible. As the public becomes savvier and more aware of the potential harm that can be caused by data breaches, they are less tolerant of delayed notifications. Even a lag of as little as a week can incur consumer wrath.

In the case of Equifax, the company reportedly spent six weeks investigating its data breach and preparing notifications. Forensic investigators, law enforcement agents, data breach attorneys, and other professionals involved in data breach management know that six weeks is a common notification window (certainly well within HIPAA’s 60-day period, for example)—but this was not your average breach. The theft of 145.5 million SSNs meant that organizations throughout the United States could no longer rely on SSNs as a means of authenticating consumers. (Of course, as outlined in Chapter 5, “Stolen Data,” much of the data was already stolen anyway, but until the Equifax breach occurred, most U.S. citizens maintained a healthy denial.) From the public’s perspective, every day that Equifax waited to disclose was one more day that affected individuals did not have the opportunity to protect themselves from potential harm.

When the notification delay stretches to years, you have a lot of explaining to do, and the delay may be far more damaging than the breach itself—as Yahoo discovered in 2016 when its data breach was finally uncovered.

“If a breach occurs, consumers should not be first learning of it three years later,” said Senator Mark Warner of Virginia, in response to Yahoo’s breach notification. “Prompt notification enables users to potentially limit the harm of a breach of this kind, particularly when it may have exposed authentication information such as security question answers they may have used on other sites.”20 This reflected a notable advancement in the public’s demonstrated understanding of data breaches: By the end of 2016, many people recognized that the compromise of their account credentials from one vendor could enable attackers to gain access to other accounts as well.

20. Hayley Tsukayama, “It Took Three Years for Yahoo to Tell Us about Its Latest Breach. Why Does It Take So Long?” Washington Post, December 19, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2016/12/16/it-took-three-years-for-yahoo-to-tell-us-about-its-latest-breach-why-does-it-take-so-long.

3.2.6 Uber’s Skeleton in the Closet

Woe to the company that keeps a data breach secret—and then eventually is unmasked.

Uber is one such company. In 2016, Uber fell victim to cyber extortion—and made a bad choice. An anonyous hacker (who called himself “John Dough”) emailed the company, claiming to have found a vulnerability and accessed sensitive data. It turned out that he had gained access to the company’s cloud-based repository at GitHub, where he found credentials and other data that enabled him to break into Uber’s Amazon web servers, which housed the company’s crown jewels—source code and data on 57 million customers and drivers (including approximately 600,000 driver’s license numbers).

The hacker politely but firmly demanded a payoff for the discovery of the “vulnerability.” At the time, Uber had a bug bounty program, managed by the speciality company HackerOne. After verifying the hacker’s claims, Uber discussed payment for the hacker’s report. Rob Fletcher, Uber’s product security engineering manager, informed John Dough that the bug bounty program’s typical top payment was $10,000. The hacker demanded more.

“Yes we expect at least 100,000$,” the hacker wrote back. “I am sure you understand what this could’ve turned out to be if it was to get into the wrong hands, I mean you guys had private keys, private data stored, backups of everything, config files etc. . . . This would’ve heart [sic] the company a lot more than you think.”21

21. “Uber ‘Bug Bounty’ Emails,” Document Cloud, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4349230-Uber-Bug-Bounty-Emails.html (accessed March 19, 2018).

Uber acquiesced and arranged for payment of $100,000. It turned out that there were actually two hackers—the original “John Dough,” based in Canada, and a second person—a 20-year-old man in Florida who had actually downloaded Uber’s sensitive data. According to reports, “Uber made the payment to confirm the hacker’s identity and have him sign a nondisclosure agreement to deter further wrongdoing. Uber also conducted a forensic analysis of the hacker’s machine to make sure the data had been purged.”22

22. Joseph Menn and Dustin Volz, “Exclusive: Uber Paid 20-Year-Old Florida Man to Keep Data Breach Secret: Sources,” Reuters, December 7, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-uber-cyber-payment-exclusive/exclusive-uber-paid-20-year-old-florida-man-to-keep-data-breach-secret-sources-idUSKBN1E101C.

Internally, the case was managed by Uber’s CSO, John Sullivan, and the company’s internal legal director, Craig Clark. Reportedly, Uber’s CEO at the time, Travis Kalanick, was briefed. Uber’s team made the decision that notification was not required, and the case was closed—or so they thought.

3.2.6.1 Housecleaning

The case probably would have stayed closed forever, but in 2017, Uber’s CEO resigned amid a growing scandal that revealed pervasive unethical and in some cases illegal behavior at the company. The new CEO took the reins in September 2017. The company’s board initiated an internal investigation of the security team’s activities, enlisting the help of an outside law firm. As part of this investigation, the unusual $100,000 “bug bounty” payment was uncovered—and investigated. The company also hired the forensics firm Mandiant to take an inventory of the affected data.

Cleaning the skeletons out of the closet was very important for Uber’s new leadership team. In order to rebuild trust with key stakeholders and the public, they needed to demonstrate openness and honesty. Any scandals that remained hidden could come back to haunt the new leadership team, which they did not want to risk. This was especially important given Uber’s rocky financial footing; were the company to be sold, the breach might well have come out during a cyber diligence review later. Exposing Uber’s dirty secrets all at once allowed Uber’s new team the opportunity to control the dialogue, point the finger at the old management, and continue on with a clean(ish) slate. As a result, Uber’s data breach case was cracked wide open.

On November 21, 2017, Uber’s new CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, released a statement disclosing the company’s “2016 Data Security Incident.” In this statement, he revealed that the names and driver’s license numbers for 600,000 drivers had been downloaded, in addition to “personal information of 57 million Uber users around the world.” Khosrowshahi specifically called out Uber’s failure to notify data subjects or regulators as a problem, and announced that the company’s CSO John Sullivan and attorney Craig Clark had been fired, effective immediately.23

23. Menn and Volz, “Exclusive.”

“None of this should have happened, and I will not make excuses for it,” he wrote. “While I can’t erase the past, I can commit on behalf of every Uber employee that we will learn from our mistakes.”24

24. Dara Khosrowshahi, “2016 Data Security Incident,” Uber, November 21, 2017, https://www.uber.com/newsroom/2016-data-incident.

3.2.6.2 Fallout

Angry riders and drivers immediately took the company to task on social media—not just for the breach itself, but for the way it was handled. Days later, two class-action lawsuits were filed against the ride-sharing company. Washington State, as well as Los Angeles and Chicago, filed their own lawsuits. Attorneys general from around the country began investigating, and in March 2018, Pennsylvania’s state attorney general announced that he was suing Uber for violating the state data breach notification law.

“The fact that the company took approximately a year to notify impacted users raises red flags within this committee as to what systemic issues prevented such time-sensitive information from being made available to those left vulnerable,” said U.S. Representative Jerry Moran (R-KS).25

25. Naomi Nix and Eric Newcomer, “Uber Defends Bug Bounty Hacker Program to Washington Lawmakers,” Bloomberg, February 6, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-06/uber-defends-bug-bounty-hacker-program-to-washington-lawmakers.

Uber’s chief information security officer, John Flynn, was called to testify before Congress about the breach. A large part of his testimony was in defense of the bug bounty program, which had come under fire due to its role in the cover-up. “We recognize that the bug bounty program is not an appropriate vehicle for dealing with intruders who seek to extort funds from the company,” Flynn said. “The approach that these intruders took was separate and distinct from those of the researchers in the security community for whom bug bounty programs are designed. . . . [A]t the end of the day, these intruders were fundamentally different from legitimate bug bounty recipients.”

3.2.6.3 Effects

The Uber case rocked the boat for third-party breach response teams, who frequently based decisions of disclosure on a risk analysis. Many breach coaches and security managers would have reached the same conclusions as Sullivan and Clark. After all, the hacker had signed an NDA, and the company had conducted a forensic analysis of his laptop. For many attorneys, this would have been considered sufficient evidence to conclude that there was a low risk of harm.

Deferring to outside counsel may have helped. There is no public evidence that Sullivan and Clark called upon an outside cybersecurity attorney for legal assistance in this case. Involving outside counsel allows internal staff to defer to an experienced third party with regards to disclosure decisions, providing significant protection for the internal team in the event that the decision is later questioned. Given the complex state of cybersecurity regulation and litigation, it is always safest to involve outside counsel. Had Uber’s investigative team chosen to involve outside counsel, they may well have reached a different conclusion.26

26. Louise Matsakis, “Uber ‘Surprised’ by Totally Unsurprising Pennsylvania Data Breach Lawsuit,” Wired, March 5, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/uber-pennsylvania-data-breach-lawsuit.

As shocking as the Uber disclosure was, one has to question whether it was truly outside the norm. It’s safe to say that if Uber had not chosen to report the 2016 breach, it most likely never would have been revealed. How many companies today have similar skeletons in the closet that may never be uncovered?

3.3 Equifax

Now that we’ve introduced the principles of crisis communications and image repair, let’s analyze the Equifax breach response. Recall the “3 C’s of Trust”:

Competence - Capable of skillfully executing one’s job

Character - Strong adherence to good values, including loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage

Caring - Genuine concern for the well-being of others

As we will see, Equifax’s response caused stakeholders to question all three of these factors, which badly damaged Equifax’s image and exacerbated the crisis.

3.3.1 Competence Concerns

After announcing the breach on September 7, 2017, Equifax was immediately off on the wrong foot. Consumers rushed to freeze their credit, only to find that Equifax’s freeze request page was unresponsive.27

27. Brian Krebs, “Equifax Breach: Setting the Record Straight,” Krebs on Security, September 20, 2017, https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/09/equifax-breach-setting-the-record-straight.

Equifax also set up a website that consumers could visit to find out whether their data was exposed, but as investigative journalist Brian Krebs reported, the site was “completely broken at best, and little more than a stalling tactic or sham at worst.”28

28. Brian Krebs, “Equifax Breach Response Turns Dumpster Fire,” Krebs on Security, September 8, 2017, https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/09/equifax-breach-response-turns-dumpster-fire.

The site asked consumers to submit the last six digits of their SSNs in order to determine whether they were affected. Consumers who did enter their information received vague and often conflicting results. Krebs reported that “[i]n some cases, people visiting the site were told they were not affected, only to find they received a different answer when they checked the site with the same information on their mobile phones.”29 Krebs himself did not receive a yes-orno answer, but rather “a message that credit monitoring services we were eligible for were not available and to check back later in the month.” These responses were infuriating for consumers, who were anxious and frustrated that the promised corrective action was not available.

29. Krebs, “Equifax Breach Response.”

Tensions were further inflamed when consumers discovered that in order to sign up for Equifax’s free TrustedID credit monitoring service, the terms of use required them to forfeit their rights to participate in a class-action lawsuit (language that Equifax later said had been included inadvertently). Equifax quickly changed the language following public outcry.30

30. Mahita Gajanan, “Equifax Says You Won’t Surrender Your Right to Sue by Asking for Help After Massive Hack,” Time, September 11, 2017, http://time.com/4936081/equifax-data-breach-hack.

Ironically, many web browsers flagged the breach information site as a phishing attack in the first few hours after the announcement. To make matters worse, the site was riddled with security holes. “[V]ulnerabilities in the site can allow hackers to siphon off personal information of anyone who visits.”31 While building a brand-new, interactive website may have been nice in theory, Equifax’s developers—reportedly associated with the outside public relations firm Edelman—clearly did a rush job.32

31. Zack Whittaker, “Equifax’s Credit Report Monitoring Site Is also Vulnerable to Hacking,” ZD Net, September 12, 2017, http://www.zdnet.com/article/equifax-freeze-your-account-site-is-also-vulnerable-to-hacking.

32. Krebs, “Equifax Breach Response”; Lily Hay Newman, “All the Ways Equifax Epically Bungled Its Breach Response,” Wired, September 24, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/equifax-breach-response.

“Talk about ham-handed responses. . . . This is simply unacceptable,” said U.S. Representative Greg Walden.33

33. Alfred Ng, “Equifax Ex-CEO Blames Breach on One Person and a Bad Scanner,” CNET, October 3, 2017, https://www.cnet.com/news/equifax-ex-ceo-blames-breach-on-one-person-and-a-bad-scanner.

Right away, Equifax appeared incompetent. This negative image was exacerbated days later, when the media discovered that Equifax’s official Twitter account had accidentally tweeted the link to a phony phishing site, securityequifax2017.com, four times during the response. “When your social media profile is tweeting out a phishing link, that’s bad news bears,” said security professional Michael Borohovski, cofounder of Tinfoil Security.34

34. Newman, “All the Ways.”

As details of Equifax’s cybersecurity issues were exposed, it painted an increasingly ugly picture. Just days after the breach was announced, Krebs reported a ridiculous vulnerability in a portal used by Equifax Argentina employees for credit dispute management: the portal was “wide open, protected by perhaps the most easy-to-guess password combination ever: ‘admin/admin.’”35

35. Brian Krebs, “Ayuda! (Help!) Equifax Has My Data!” Krebs on Security, September 12, 2017, https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/09/ayuda-help-equifax-has-my-data.

Two days later, Equifax confirmed in a statement that the megabreach had been caused when hackers broke into a web server, exploiting a well-known vulnerability in the Apache Struts framework. The vulnerability had been announced in March 2017, and Equifax was hacked in May—meaning that the company had more than two months to patch the system but didn’t.36 Equifax announced the cause only after a research firm published an uncited report implicating the Apache Struts vulnerability, which sparked rumors.37 The day after the statement was released, the company’s chief information officer and chief security officer stepped down.

36. Lily Hay Newman, “Equifax Officially Has No Excuse,” Wired, September 14, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/equifax-breach-no-excuse.

37. Robert W. Baird & Co., “Equifax Inc. (EFX) Announces Significant Data Breach; -13.4% in After-Hours,” Baird Equity Research, September 7, 2017, https://baird.bluematrix.com/docs/pdf/dbf801ef-f20e-4d6f-91c1-88e55503ecb0.pdf.

Equifax’s CEO later blamed an employee for not installing the patch and said a subsequent security scan did not detect the issue. Consumers didn’t buy the excuse, if it was one.

Senator Elizabeth Warren tweeted: “It’s outrageous that Equifax—a company whose one job is to collect consumer information—failed to safeguard data for 143M Americans.”38

38. Brad Stone, “The Category 5 Equifax Hurricane,” Bloomberg, September 11, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-11/the-category-5-equifax-hurricane.

3.3.2 Character Flaws

The integrity of Equifax, as a corporation, as well as its leadership team, was called into question immediately due to the length of time taken before notifying. “Equifax waited six weeks to disclose the breach,” wrote reporter Michael Hiltzik in the Los Angeles Times the day following the company’s announcement. “That’s six weeks that consumers could have been victimized without their knowledge and therefore left without the ability to take countermeasures. Equifax hasn’t explained the delay.”39 It wasn’t just the public that was kept in the dark; CEO Smith also waited 20 days to inform the company’s board, despite the massive scale of the breach.40

39. Michael Hiltzik, “Here Are All the Ways the Equifax Data Breach Is Worse than You Can Imagine,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 2017, http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-equifax-breach-20170908-story.html.

40. Liz Moyer, “Equifax’s Then-CEO Waited Three Weeks to Inform Board of Massive Data Breach, Testimony Says,” CNBC, October 2, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/10/02/equifaxs-then-ceo-waited-three-weeks-to-inform-board-of-massive-data-breach-testimony-says.html.

The delay triggered deep suspicion. “New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman wants to know when the company learned about the breach and how exactly it happened,” Bloomberg reported. Questions of integrity grew when it became known that three senior Equifax executives had sold shares in the company worth nearly $2 million in the days following the breach discovery.

3.3.3 Uncaring

In the aftermath of the breach announcement, Equifax’s call centers couldn’t come close to handling the flood of phone calls. Consumers were infuriated. The lack of two-way communication contributed to a growing sense that Equifax did not actually care about the consumer.

Later, in his congressional testimony, former CEO Smith apologized:43

43. U.S. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, Prepared Testimony of Richard F. Smith.

We were disappointed with the rollout of our website and call centers, which in many cases added to the frustration of American consumers. The scale of this hack was enormous and we struggled with the initial effort to meet the challenges that effective remediation posed. The company dramatically increased the number of customer service representatives at the call centers and the website has been improved to handle the large number of visitors. Still, the rollout of these resources should have been far better, and I regret that the response exacerbated rather than alleviated matters for so many.

Smith closely integrated his personal image with Equifax’s breach response. On the same day as the breach announcement, Equifax released a video featuring Smith—presumably in an attempt to humanize the company. It didn’t do them any favors. Smith essentially read the company’s statement out loud with a wooden expression, looking like a deer in headlights. Although Equifax wisely included an explicit apology in the message, it was buried halfway through the video, and the words were not enough to overcome Smith’s strained, unemotional demeanor.44

44. Equifax, “Rick Smith, Chairman and CEO of Equifax, on Cybersecurity Incident Involving Consumer Data,” YouTube, September 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bh1gzJFVFLc.

The Equifax breach quickly exploded into a “dumpster fire” (as Krebs put it). Smith was forced to resign after a 12-year tenure, just weeks after the breach was announced.

3.3.4 Impact

Equifax’s communications following its breach left stakeholders with the following impressions:

Incompetent - Smith did not oversee Equifax’s cybersecurity program effectively, as evidenced by the breach and gross fumbles with technology in the company’s response.

Lack of Character - Equifax’s delayed notification, along with rumors of an executive stock dump during the breach investigation, caused the public to question the integrity of the company and its leadership.

Uncaring - Smith’s wooden performance in Equifax’s public relations video, combined with the call center frustrations, left the strong impression that Equifax did not care about consumers.

As a result, the breach badly damaged Equifax’s image and destroyed trust that key stakeholders had in the company’s leadership.

Throughout the acute phases of the crisis, Equifax’s stock value clearly changed based on the company’s communications. Stock prices fell from $142.72 on the day of the announcement to a low of $92.98 a week later on September 15, 2017, as shown in Figure 3-2. Things started to pick up with the resignation of the CIO and CSO; clearly shareholders began to rebuild confidence with a change of management. With Smith’s resignation, Equifax’s stock rose yet again. By the end of the year, share prices were still down, but slowly recovering.

3.3.5 Crisis Communications Tips

There are many lessons to be learned from the Equifax breach, but perhaps none are so well illustrated and so poignant as those relating to crisis communications. In today’s day and age, many CEOs—too many—will find themselves in much the same position as Smith.

In those first few hours, days, and weeks, keep in mind the following priorities:

Maintain Trust with Your Stakeholders. Remember the 3 C’s: Competence, Character, and Caring.

Tell It Early, Tell It Yourself. Maintain a congenial relationship with the media. By providing a quote when contacted by the press, you send the message that you are not trying to hide.

Tell the Truth. If you tell the truth, you won’t have to suffer the consequences of a scandalous lie.

Make It a “One-Day” Story. Few data breach stories are ever really one day, but get as close as you can by consolidating announcements and responding to the press as quickly as possible. Don’t give journalists incentive to “dig.”

Take Responsibility. This is the foundation for rebuilding trust.

Apologize Clearly and Quickly. A sincere apology diffuses anger and shows respect for your stakeholders.

Listen! Prepare your staff to listen to stakeholders. For example, you might consider opening a call center in response to the breach, so that members of the public can quickly speak with a real human. Likewise, shareholders, regulators, and other stakeholders need a point of contact who can listen to their concerns and diffuse strong emotions.

Make Sure Your Tools Work. Too often, when a breach occurs, breached companies offer services to the public, such as a hotline or credit monitoring, but the technology or processes to support them are broken or not immediately available. This further inflames sentiments.

Make Amends. Use image repair tactics such as compensation or corrective action to restore your organization’s image.

3.4 Conclusion

In this chapter, we showed how data breaches are typically crises and introduced Steven Fink’s four stages of a crisis. We also showed how the “3 C’s of Trust” relate to crisis communications and discussed the fundamentals of image repair theory. Finally, we analyzed the Equifax breach and showed how flaws in the company’s crisis communications strategy turned its crisis into a public relations “dumpster fire.”

Now that we understand how the fundamentals of crisis management relate to data breaches, let’s use this to devise a model for our response.