Chapter 6. Payment Card Breaches

In March 2008, Cissy McComb, owner of Cisero’s Ristorante, called the Park City, Utah, police department. She had just received a letter from Elavon, her restaurant’s payment processor, notifying her that “payment cards used at Cisero’s may have been accessed, counterfeited and fraudulently used elsewhere.” Visa had identified the restaurant as a “common point-of-purchase” for a group of stolen cards and notified the bank. Cisero’s was a mom-and-pop Italian restaurant located on Main Street in Park City. Steve and Cissy McComb had opened the restaurant in 1985 and ran it for 30 years. During the summertime Sundance Festival, Cisero’s was packed with flashy stars and visiting tourists. The owners bragged that Robert Redford, Sandra Bullock, and Russell Crowe had dined there. Sidney Poiter once set his menu on fire by accidentally touching it to the flickering table candle. The rest of the year, Cisero’s was a local staple.1

1. Bubba Brown, “Cisero’s Ristorante, a Park City Mainstay, Closes Doors,” ParkRecord.com, July 22, 2016, https://www.parkrecord.com/news/business/ciseros-ristorante-a-park-city-mainstay-closes-doors.

Now, Mrs. McComb was worried. After calling the Park City police department, Mrs. McComb drove to her local branch of U.S. Bank, which in 2001 had arranged for its affiliated payment processor, Elavon, to handle the restaurant’s credit card processing. None of her local branch’s staff knew anything about a suspected breach.

In June, Mrs. McComb received another worrisome letter. Elavon notified the couple that they would be fined $5,000 for the breach and would need to provide a certificate of “PCI compliance” in approximately a month, or they would face additional fines. Subsequently, U.S. Bank “unilaterally” deducted $5,000 from the restaurant’s account. The McCombs submitted an attestation of PCI compliance and paid approximately $41,000 to upgrade their point-of-sale (POS) systems.

Behind the scenes, the couple later discovered that Visa had sent U.S. Bank a letter stating: “If Cisero’s Ristorante and Nightclub does not demonstrate . . . compliance within 30 days from the date of this letter, U.S. Bank will be assessed a monthly fine of $5,000.” The fines would increase to $10,000 or more per month after 90 days. Although U.S. Bank had the right to appeal these fines, the bank would have had to pay a nonrefundable $5,000 fee to Visa just to submit an appeal, which would have been added to the restaurant’s accrued liability.

The McCombs also received notice from Elavon that they were required to conduct a forensic investigation, at their own expense. Elavon provided them with a list of six forensics companies that were approved by Visa and Mastercard to conduct the investigations. The McCombs selected a firm named Cybertrust. Cybertrust investigated and found that there was “no concrete evidence” of a security breach, and “no evidence of intrusive, malicious, or unauthorized activity.” The McCombs hired a second forensics firm as well, which reached similar conclusions.2

2. Elavon, Inc. v. Cisero’s Inc., Civil No. 100500480 (3d Jud. Dist. Ct., Summit Cty., 2011), https://www.wired.com/images_blogs/threatlevel/2012/01/Cisero-PCI-Countersuit.pdf.

Nonetheless, U.S. Bank deducted more than $5,000 from the McCombs’ bank account again, without their consent, after Mastercard reported that issuers including Chase and RBS had reported fraudulent charges and were seeking to recover damages. According to news reports, “Visa determined that the total cost of the liability for Cisero’s noncompliance was $1.33 million, but ultimately set the fine at $55,000. . . . MasterCard stated that although it could have imposed a fine of up to $100,000 for the violation of storing card data, it decided to impose a fine of only $15,000.”

The McCombs quickly closed their bank account to avoid any further deductions. Elavon sued for approximately $82,600 in additional fines. The McCombs fought back, filing a countersuit. “It’s just like Visa and MasterCard are governments,” said the couple’s attorney, Stephen Cannon. “Where do they get the authority to execute a system of fines and penalties against merchants?”3

3. Kim Zetter, “Rare Legal Fight Takes on Credit Card Company Security Standards and Fines,” Wired, January 11, 2012, https://www.wired.com/2012/01/pci-lawsuit.

After a burst of media attention, the case was settled quietly out of court.

6.1 The Greatest Payment Card Scam of All

Payment card breaches can be very complex and result in years of litigation. They can damage a merchant’s reputation with consumers and even drive a business out of business. In a payment card breach, consumers’ credit or debit card numbers are exposed. The card numbers are often distributed through the dark web or other channels, and then criminals monetize them by making card-not-present purchases or by creating fake cards, which they can then use or resell for a percentage of the balance.

Over the years, payment card information has consistently ranked at the top of data compromise charts (topped only by the more generic “personal information” such as name, Social Security number (SSN), etc).4 This is for two reasons: First, payment card information is at extremely high risk of theft; and second, when a cardholder data breach occurs, it is very likely to be detected (more so than other types of breaches).

4. 2016 Data Breach Investigations Report, Verizon Enterprise, 2016, 44, https://enterprise.verizon.com/resources/reports/2016/DBIR_2016_Report.pdf.

Why does cardholder data present such a high risk of a data breach? It is because payment card security is obviously broken, in that it relies upon a shared secret that, really, isn’t much of a secret at all. Your card number is essentially the “key” to your account. In order to keep your account secure, you must keep this long number very very secret—but in order to actually use it, you have to share it with many people. This system is fundamentally flawed.

Payment card numbers are small and compact—very liquid. They proliferate with use. Many people have access to them, from waiters to billing clerks to IT administrators. They are valuable on the black market, for obvious reasons. Often organizations choose to store payment card data for extended periods of time, to facilitate autopay and speed transactions. In short, all five of the data breach risk factors apply: retention, proliferation, access, liquidity, and value.

Today, there are far more secure ways to conduct payment transactions. Mobile devices and advances in cryptographic authentication have the potential to render the risky payment card number obsolete. Without payment card numbers, there would be no cardholder data breaches. That would mean merchants would not need to worry about securing vast volumes of sensitive payment card numbers that pass through their systems. Banks would not have to invest (as much) in fraud monitoring or reissuing of cards. Consumers would not have to pay the price of cardholder data breaches, in the form of increased fees and prices.

Given the high rate of data breaches and resulting fraud, why do we still rely on insecure payment card numbers? While some progress has been made over the years, a complete overhaul of the system would require a huge investment from card brands, payment processors, merchants, and every entity involved. In the meantime, the more powerful players (card brands and banks) have developed “Band-Aids” (mechanisms for detecting fraud early and recouping losses after a breach), sometimes at the expense of less-powerful entities.

Behind the scenes, the card brands in particular have amassed enormous control over the process of sorting out liability and have effectively pitted other key players against each other. The payment card industry is self-regulated with respect to cybersecurity, and it has implemented contractual obligations that can feel to participants like governmental regulations (even though they are not). Card brands—such as Visa, Mastercard, Discover, and American Express—write the rules for their payment networks. Based on their contracts, banks and merchants are responsible for absorbing the majority of the losses, rather than the card brands themselves. Merchants, payment processors, and others who handle payment cards have no choice but to follow the card brands’ rules, lest they be denied the ability to accept payment cards—the lifeblood of our modern economy.

The result is that when a cardholder data breach happens, merchants—even small ones—can be left holding the bag. Banks are caught in the middle, torn between their allegience to customers and their own bottom line. Even forensics firms that investigate cardholder data breaches are subtly controlled: They must answer to the card brands in order to be “qualified” to investigate payment card breaches.

In this chapter, we will explore the different players involved in a payment card breach and the deep network of factors that influences their actions. Along the way, we will specifically examine how the standards established by the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI SSC) affect various parties before and after a breach. We will step through the TJ Maxx and Heartland data breaches, which established strong precedents for determining liability, and show how compliance with the PCI SSC’s standards affect breach response best practices.

6.2 Impact of a Breach

Fraud is rampant, and no one wants to be stuck covering the losses. This fundamental issue is at the heart of payment card data breach response. Many different participants are affected by a payment card breach, including:

Consumers

Banks

Payment processors

Merchants

Card brands

In this section, we will discuss the impact of payment card breaches on each of these participants.

6.2.1 How Credit Card Payment Systems Work

In order to understand who foots the bill for a credit or debit card data breach, you first have to understand, at a high level, how payment card networks work. Different card brands have slightly different setups: typically a “three-party scheme” or “four-party scheme.”

Visa and Mastercard use four-party schemes, as illustrated in Figure 6-1. In four-party schemes, each transaction involves four participants: the cardholder, the issuer (the cardholder’s bank), the acquirer (the merchant’s bank), and the merchant. In between, card brands and payment processors help to communicate transaction data and move funds. In the Cisero’s v. Elavon countersuit, the four parties were eloquently defined as follows:5

5. Elavon v. Cisero’s.

Cardholder. A cardholder is a consumer who makes a purchase from a merchant using an electronic payment card.

Merchants. When a cardholder makes an in-person transaction, the cardholder’s credit or debit card is swiped at a merchant’s POS terminal.

Acquirers. Acquirers are merchant’s banks, such as U.S. Bank, that “acquire” transactions by providing merchants with access to the payment networks and maintaining amounts due to the merchant. Acquiring banks usually contract with a processor, such as Elavon, to provide merchants with authorization, clearance, and settlement transaction services.

Issuers. Issuers are cardholders’ banks, such as Bank of America or Wells Fargo, that issue credit and debit payment cards to retail customers.

Let’s walk through a typical transaction. When a cardholder (A) purchases a product or service using his card, the issuing bank (B) authorizes the transaction. Once authorization is received, the acquirer (C) transfers money to the merchant (D), minus a service fee. The issuing bank sends money to the acquirer (minus any interchange fee) and debits the cardholder’s account.

Three-party schemes, such as those used by American Express and Discover, are similar except that the issuer and the acquirer are the same brand. This is why your local bank may issue you a Visa- or Mastercard-branded card, but not an American Express or Discover card.

6.2.2 Consumers

Consumers, naturally, are impacted by payment card fraud when money is stolen from their accounts or charged to their credit cards. This can have a chilling effect, making consumers more reticent to hand their card number to merchants. Payment card breaches are bad for business—and therefore bad for everyone in the payment processing chain. “When someone hacks a site, it raises a lot of questions to the consumer,” commented Chris Merritt, a consultant for retailers.6

6. Paul A. Greenberg, “Online Credit Card Security Takes Another Hit,” January 20, 2000, E-Commerce Times, https://www.ecommercetimes.com/story/2291.html.

To protect the public, the United States passed a federal law that mandates that consumers are liable only for the first $50 of fraudulent charges.7 Some card associations took that even further: Visa, for example, instituted a “zero-liability” policy, to reassure consumers. Credit card companies “tout[ed] antifraud campaigns” and promised that “cardholders won’t have to pay a dime” if their cards were used fraudulently.8

7. United States Code, 15 U.S.C. 1643: Liability of Holder of Credit Card (Washington, DC: GPO, 2006) https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/USCODE-2011-title15/USCODE-2011-title15-chap41-subchapI-partB-sec1643.

8. Paul Beckett and Jathon Sapsford, “A Tussle over Who Pays for Credit-Card Theft,” Wall Street Journal, May 1, 2003, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB105173975140172900.

“Zero-liability” didn’t stop consumer horror stories from hitting the news. In one feature, consumer Karen Jones purchased music online from CD Universe before her credit card number was exposed by Maxus’s credit card data pipe. While Jones wasn’t responsible for the financial loss, she said that the theft had “caused her a considerable amount of grief,” estimating that she had spent approximately 10 hours a week for months “corresponding with credit card companies and dozens of merchants and vendors to get more than $4,000 in fraudulent charges removed from her account.” Over the years, banks invested heavily in fraud prevention systems to minimize the impact on consumers even after card numbers were stolen.

If consumers aren’t liable for the fraudulent charges, who is? Clearly, the money has to come from somewhere. Criminals aren’t giving it back.

6.2.3 Poor Banks

The issuing banks often bear the brunt of losses due to cardholder data breaches. When a credit or debit card number is stolen and a criminal makes a fraudulent charge, the issuing bank typically bears the responsibility for making the cardholder whole again. The issuer can try to recover the money from the merchant’s bank (the acquirer), which in turn can attempt to recoup the costs from the merchant. (In some cases, there are other payment facilitators in the chain, which may bear some responsibility.) This system has led to many conflicts between the issuers and merchants, as the case of Cisero’s illustrated.

When a cardholder data breach is detected, the issuer has a choice: to cancel the card and reissue it, or to allow the card to remain active and monitor it for fraud. Both options are costly. If the bank chooses to reissue, cardholders are often annoyed because their card may suddenly not work, and they may need to provide new card numbers to merchants with whom they have set up autopay. If the bank does not reissue, then a fraudster may attempt to use the card number, resulting in losses. Given the prevalence of cardholder data breaches, banks often choose the latter approach: They simply monitor affected accounts for fraud and have additional controls in place to minimize risk.

6.2.4 Poor Merchants

Merchants who experience a cardholder data breach may be on the hook for thousands if not millions of dollars. When cardholder data is stolen from a merchant’s network or POS system and subsequently used for fraud, the banks may attempt to recover losses from the merchant. As we will see from the TJ Maxx breach later in this chapter, they are often successful. Typically the banks still lose money; the amounts that they recover from the merchant’s bank don’t cover the cost of reissuing cards, or customer goodwill, or even the entire amount of fraudulent charges in many cases.

What’s more, the card brands may levy steep fines against the merchant’s acquiring bank, particularly if there is evidence that they were not compliant with industry security standards. As in the case of Cisero’s, the acquirer may then charge the merchant for these fines. The acquirer has the right to do this because of its contract with the merchant.

Merchants also lose out when they process fraudulent transactions due to stolen payment card numbers. For example, Gary Howell, the owner of a mail-order auto-parts business in West Virginia, discovered that a remote customer had bought $4,200 in car parts—using a stolen American Express card. He was told that the loss was his responsibility. When he called American Express asking for help tracking down the fraudster, an American Express spokesperson said the company had a “no prosecute” policy and refused to help.9 All over the globe, merchants who send goods or provide services in exchange for a fraudulent credit card transaction risk losing the value of whatever it was they provided.

9. Beckett and Sapsford, “Tussle.”

6.2.5 Poor Payment Processors

Payment processors are intermediaries that facilitate communication between merchants, card brands, and banks. When a customer provides a merchant with a payment card, a payment processor will manage tasks such as determining whether the customer has sufficient credit to make a charge (“authorization”) or directing the banks to debit the customer’s account and release funds to the merchant (“settlement” and “funding”).

Much like merchants, payment processors can be victims of cardholder data breaches, in which case they may be liable for resulting losses. Later in this chapter, we will study the Heartland payment processor breach, which was a landmark case.

Payment processors also take a hit when they unknowingly process fraudulent transactions, in the form of fees that are charged by the card brands. For example, Website Billing Inc., a company that processed payments on behalf of online retailers, got in a major public battle with Visa over transaction fees. According to Website, Visa required it to pay $15 for every fraudulent transaction that the company processed. On top of that, “when fraudulent purchases exceeded 5% of all its international transactions, Visa began slapping on an additional $100 penalty for each bogus transaction.” Website took Visa to federal court over the fines. Ultimately, the parties settled, and Website was required to pay Visa more than $1 million.10

10. Beckett and Sapsford, “Tussle.”

6.2.6 Not-So-Poor Card Brands

Card brands have a leg up: They write the rules for their payment networks. Contractually, banks and merchants are responsible for absorbing the majority of the losses rather than the card brands.

In addition, card brands can levy fines against the other parties in the system and charge extra fees to cover the cost of fraud. Card associations argue that their extra fees are designed to “cover the cost of processing bogus transactions, much like banks charge for bounced checks.”11

11. Beckett and Sapsford, “Tussle.”

Some parties have speculated that card brands such as Visa and Mastercard even turned a profit from the extra fees. “Their response [to credit card fraud] has been very slow because they have been able to pass the cost along to merchants and in the process levy fines that lead to a net gain for banks in the system,” said an attorney for Website, Michael Chesal.

Mastercard’s chief executive officer (CEO) responded, pointing out that “I don’t think anybody cavalierly sits back and says, ‘We can poison the well from which the industry drinks.’”12

12. Beckett and Sapsford, “Tussle.”

Over the years, the card brands have developed a complex set of cybersecurity standards that all the other parties in the system must follow. As we will see, these standards effectively place the responsiblity for security (and losses) on merchants, payment processors, banks, and the other participants in the system.

6.2.7 Poor Consumers, After All

As merchants and banks continued to suffer escalating losses due to data breaches and fraud, they passed the costs along to consumers, via price hikes and transaction fees. While consumers may have “zero liability” for specific fraudulent transactions, ultimately, they bear the costs.

6.3 Placing Blame

Everyone knows payment card fraud is rampant—but whose fault is it? This question is critical for determining (a) who should be liable for the losses, and (b) who is responsible for fixing the problem.

6.3.1 Bulls-Eye on Merchants

When cardholder data is stolen, it is typically through one of the following methods:

Internal network breach: Hackers break into a merchant’s or payment processor’s network and capture payment card data as it is stored, processed, or transmitted. Often, POS systems on a merchant’s internal network are specifically targeted and compromised. The risk of an internal network breach is compounded by the fact that merchants often store credit card data for extended periods of time, unwittingly stockpiling troves of hazardous material.

E-Commerce website hack: Many e-commerce websites have vulnerabilities, which enable criminals from around the world to subvert their payment systems and, in some cases, gain remote access to sensitive internal servers and databases as well.

Physical theft: Criminals place “skimmers” on top of legitimate card readers to capture the encoded information from the magnetic stripe or simply copy card data when it is handed over by a consumer (e.g., as in the case of a waiter or retail clerk). Physical theft is relatively low volume compared with the enormous databases that can be exposed through other methods.

The place where the payment card data is breached is, of course, the most visible and the most obvious point of failure. Merchants in particular are at very high risk of a breach, for the following reasons:

Merchants collectively handle extensive volumes of payment card data.

Merchants’ payment processing systems are exposed to the public and therefore to criminals. For example, local merchants have open stores where people physically walk through and interact directly with POS systems. E-commerce sites are, by nature, directly connected to the Internet.

Merchants are not in the security business (or, not usually)! They simply want to process payments. In fact, many merchants are mom-and-pop businesses with limited IT support and few funds to invest in security.

For these reasons, merchants represent a very high-risk point in the payment card system.

6.3.2 Fundamentally Flawed

Merchants can increase or decrease the risk depending on how well they secure their environments, but ultimately, they cannot fix what is a fundamentally insecure system.

The current payment card system places merchants in a particularly risky position. It’s important to recognize that this is not the only possible system; there are other payment methods that are far less risky for merchants, with respect to data breaches. New forms of payment systems have emerged, such as PayPal and ApplePay, which do not require merchants to handle payment card numbers at all. Transactions can be authenticated without static card numbers, rendering the very concept of payment card data breaches obsolete.

However, none of these new solutions has become as widely adopted as traditional magnetic-stripe cards encoded with a very long number. “The technology needed to support [stronger authentication] is available and can be implemented fairly easily . . . but few banks appear to be doing so,” observed Gartner analyst Aviva Litan.13

13. Kim Zetter, “That Big Security Fix for Credit Cards Won’t Stop Fraud,” Wired, September 30, 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/09/big-security-fix-credit-cards-wont-stop-fraud.

Merchants undoubtedly would prefer a system that reduces their risk, but they are participants in a much bigger system that they did not architect and do not control. It is unlikely that the card brands will drive fundamental changes to the payment system security model so long as the losses they incur do not exceed the cost of a major system overhaul. The result is that payment card data breaches will continue, perhaps gradually fading away as alternate payment systems emerge over time.

6.3.3 Security Standards Emerge

As payment card data breaches proliferated, card associations and banks were quick to highlight the risk at the endpoints, such as online retailers. In response, merchants and payment processors began to push back on the card associations, complaining that they did not provide appropriate support to entities using their systems.

Pressure mounted on the payment card industry to stop the bleeding. Clearly, card associations needed to make sure consumers weren’t afraid to use the cards and quell merchants’ and banks’ growing frustration.

The card associations took action—not by fixing the fundamental problem, but with a Band-Aid. In April 2000 (shortly after the CD Universe case hit the news), Visa announced its new Cardholder Information Security Program (CISP), which would take effect in June 2001. The CISP was “intended to ensure merchants and others in the credit approval chain have appropriate security measures in place to protect cardholder information.” It included 12 security requirements, known as the “Digital Dozen.” Visa’s senior vice president of risk management, John Shaughnessy, said the company’s goal was to “create a ‘duh’ list—stuff that nobody could argue with.”14

14. Paul Desmond, “Visa is Monitoring Merchants for Security Compliance,” eSecurity Planet, June 1, 2001, http://www.esecurityplanet.com/trends/article.php/688812/Visa-is-monitoring-merchants-for-security-compliance.htm.

The “Digital Dozen” required merchants to adhere to strict security requirements and provide attestations of compliance to Visa. Visa said it would begin by verifying the compliance of its top 100 merchants and also conduct random tests of other merchants. Merchants were also required to immediately notify acquirers if they got hacked, and the acquirers, in turn, were required to notify Visa.

Other major card associations quickly followed suit. Mastercard released the “Site Data

Protection” standards, and American Express published “Data Security Operating Policy.”

Overwhelmed with multiple uncoordinated security “standards,” few merchants complied with any of them. However, the card associations had succeeded in shifting the dialogue, taking the focus away from themselves and placing responsibility for security on the merchants and other participants. There was little discussion of the real problem, which was the fundamental insecurity of the payment card model.

6.4 Self-Regulation

As the dark web matured, payment card breaches became an epidemic. The publicity and media attention on the problem was extensive, and it was clear that if the payment card industry did not regulate itself, it would run the risk that the government might step in to establish standards.

There were rumblings of regulation. “Some officials say it may be time for stricter government oversight of what kinds of financial information e-merchants keep, how long they can keep it and how they store it.”15

15. Fran Silverman, “Cyber Pirates: Hacker’s Credit Card Haul Raises Security Flag,” Hartford Courant, January 14, 2000, http://articles.courant.com/2000-01-14/business/0001140730_1_credit-card-cd-universe-card-numbers.

The payment card industry pushed back, fast. “[T]he industry needs to preserve the flexibility to find solutions as it has in the past. Legislation will not help,” wrote Oscar Marquis, former general counsel of the credit bureau TransUnion.16

16. Oscar Marquis, “ID Theft Should be Addressed by the Industry, Not Congress,” American Banker, September 13, 2002, 9.

Faced with the threat of government regulation, the payment card brands quickly banded together to form the PCI SSC. They implemented their own, self-managed industry security program, known as the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). Since its founding, the PCI SSC has developed a wide array of cybersecurity-related standards, as well as requirements for data breach response processes and forensics firms. This successfully quashed calls for legislation.

Modern payment card breach response is heavily influenced by the PCI SSC and its programs. In order to understand the dynamics of a modern payment card breach (and how best to respond), you must have a strong grasp of how the PCI SSC works and the fundamentals of the PCI DSS program. In this section, we will cover important aspects of the PCI SSC and the standards it has created. Later in the chapter, we will see how these standards have directly impacted data breach response processes and liability.

6.4.1 PCI Data Security Standard

In 2004, five major card brands came together to release the first version of the PCI DSS. In order to accept payment cards, merchants all over the world were required by contract to adhere to the detailed, technical standard. The five payment brands that created the original PCI DSS were:

Visa

Mastercard

American Express

Discover

JCB

The PCI DSS is critically important for navigating payment card breaches. The standard is marketed as a tool to “help protect the safety” of payment card data. However, as we will see, it also functions as a tool to determine liability in the event of a data breach, and is part of a broader compliance toolset that the payment card brands use to recoup costs and generate revenue. At the time that PCI DSS was first deployed, the immediate effects were to:

Quell the widespread calls for better security and regulation in the payment card industry

Place responsibility for cardholder data security squarely on merchants, processors, and other downstream entities that handled payment card data, rather than the card brands themselves

Give card brands a clear mechanism for leveraging fines and recouping costs of fraud from merchants and other downstream entities

Put the payment card brands in the driver’s seat when it came to cardholder data security standards

6.4.2 A For-Profit Standard

PCI DSS is a proprietary standard. One “tell” that it is maintained by a for-profit entity is that in order to download it, you have to enter your personal information in a form with an automatically checked box that reads, “Yes, I am interested in learning more about the PCI Security Standards Council and their training programs.” (Training programs sold by the PCI SSC typically cost between $1,000 and $3,000 per seat.) The fact that it is maintained by a for-profit entity means that the administration of the PCI compliance program can, and does, generate revenue for its owners.

As per the standard: “PCI DSS applies to all entities involved in payment card processing—including merchants, processors, acquirers, issuers, and service providers. PCI DSS also applies to all other entities that store, process or transmit cardholder data (CHD) and/or sensitive authentication data (SAD).” The PCI DSS defines “cardholder data” and “sensitive authentication data” as follows:

Cardholder Data: Primary account number (PAN), cardholder name, service code, expiration date

Sensitive Authentication Data: Full track data, CVV2, CID, CVC2, CAV2, PIN

PCI DSS includes 12 categories, as follows:17

17. PCI Security Standards Council, PCI DSS, v.3.2.1, May 2018, https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/documents/PCI_DSS_v3-2-1.pdf.

Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data.

Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and other security parameters.

Protect stored cardholder data.

Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks.

Use and regularly update antivirus software or programs.

Develop and maintain secure systems and applications.

Restrict access to cardholder data by business need to know.

Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access.

Restrict physical access to cardholder data.

Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data.

Regularly test security systems and processes.

Maintain a policy that addresses information security for all personnel.

6.4.3 The Man behind the Curtain

The PCI SSC oversees maintenance and implementation of the PCI DSS. Formed in 2006, the PCI SSC touts itself as a “global open body formed to develop, enhance, disseminate and assist with the understanding of security standards for payment account security.”18 Many people think it is a nonprofit or government entity. As we will see, it is neither—a fact that has far-reaching consequences for cybersecurity and breach response.

18. PCI Security Standards Council, “About Us,” https://web.archive.org/web/20160414051410/ https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/about_us/.

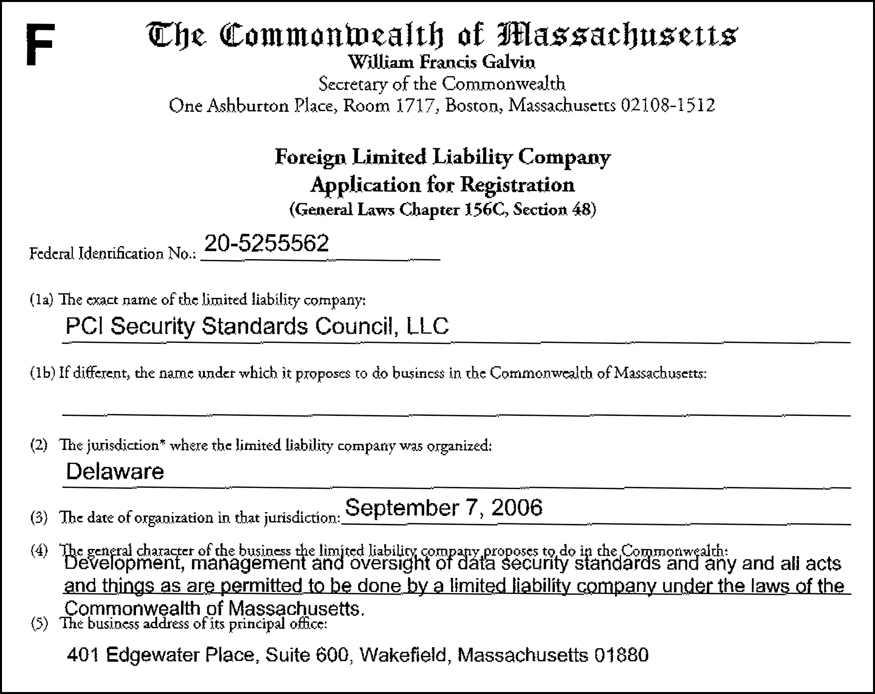

The PCI SSC’s LinkedIn page states that the organization is nonprofit, as shown in Figure 6-2, but this isn’t true. The PCI SSC is definitely non-nonprofit. As indicated in the State of Delaware’s public records, the PCI SSC is actually a limited liability company “with no special attributes such as non profit or religious.”19

19. State of Delaware, “Entity Details, File Number 4215897,” Department of State: Division of Corporations, https://icis.corp.delaware.gov/Ecorp/EntitySearch/EntitySearchStatus.aspx?i=4215897&d=y.

Corporate filings from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the State of Delaware confirm that the “PCI Security Standards Council, LLC” is a for-profit limited liability corporation formed in Delaware on September 7, 2006, and subsequently registered in Massachusetts (Figure 6-3).

The same filing indicates that LLC is managed by five members, representing VISA Holdings, Inc., Mastercard International Incorporated, JCB Advanced Technologies, Inc, Discover Financial Services, LLC, and AETRS (American Express Travel Related Services Company, Inc.), as shown in Figure 6-4.

It’s very hard to find details about the company’s revenue and ownership, although details leak out here and there. For example, Discover Financial Services’ (DFS) 2014 Annual Report to the Federal Reserve states that DFS holds a “total equity ownership of 20%” in the PCI SSC.20

20. Discovery Financial Services, Annual Report of Holding Companies, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, U.S. Federal Reserve, December 31, 2014, 2.

When examining the PCI SSC’s standards and processes for reducing the risk of data breaches, keep in mind that this is not a government regulatory agency or an independent nonprofit. It has the ability to profit off the regulatory system that it has created, and in turn, it can pass any profits along to the card associations that own it.

6.4.4 PCI Confusion

For retailers and processors that make an effort to become “PCI compliant,” the process can be fraught with confusion. The major card associations require all entities that process, store, or transmit cardholder data to fully comply with all aspects of the PCI DSS standard. However, only certain entities are required to have a third party validate their compliance, based on the number of transactions that they process each year. Visa, for example, allows most merchants that process “fewer than 20,000 Visa e-commerce transactions” and “all other merchants . . . processing up to 1M VISA transactions per year” to complete a self-assessment questionnaire, an attestation of compliance, and (in some cases) results of a vulnerability scan as evidence of compliance with PCI DSS.

Merchants and service providers that process large volumes of transactions are typically required by their card brands to have their PCI DSS compliance validated by a qualified security assessor (QSA). The QSA is an organization certified by the PCI SSC to conduct PCI DSS compliance audits. The merchant must pay for the services of the QSA.

The job of the PCI QSA is to “validate an entity’s adherence to PCI DSS.” In other words, if you are a merchant required to have a QSA validate your PCI DSS compliance, an employee from a company that is an approved QSA will review your company’s policies, procedures, and security test results; interview your staff; and go through the PCI DSS checklist to determine whether you are in compliance with each item. Then the QSA issues a report that is shared with the PCI SSC.

The PCI QSAs often have different interpretations of the rules. “The biggest challenge with PCI is that you are at the mercy of the auditors and their skill set,” said Jay White, the global information protection architect for Chevron. “With some auditors, everything becomes black and white, while others take a more nuanced view of the controls a company might have in place.”21

21. Jaikumar Vijayan, “Retailers Take Swipe at PCI Security Rules,” Computerworld, October 15, 2007, https://www.computerworld.com/article/2552354/retailers-take-swipe-at-pci-security-rules.html.

6.4.5 QSA Incentives

QSAs have an unspoken incentive to satisfy their clients—the retailers and payment processors that they evaluate. QSAs are not randomly assigned. Instead, retailers can choose from a long list of PCI QSAs. If a retailer does not like the results of a PCI assessment, it has the freedom to choose a different provider next time. This creates an inherent conflict of interest for QSAs: On the one hand, they are responsible for accurately reporting the PCI compliance status of an organization; and on the other hand, they are under significant business pressure to report what the organization wants to hear. This is in contrast to government-regulated industries, such as the financial sector, where examiners work for agencies such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the Federal Reserve.

QSAs must also stay in the good graces of the PCI SSC (which of course is owned by five payment card brands). The PCI SSC invented the concept of a QSA, and all approved firms are listed on the PCI SSC’s website. (There are 390 approved QSAs listed on the PCI SSC’s website as of March 2019.)

Becoming a QSA is a substantial investment. The QSA itself must pay hefty fees to the PCI SSC for the privilege of conducting PCI DSS assessments. Each QSA pays an initial application fee, plus a “regional qualification fee” of up to $24,000 that allows the company to conduct assessments only in that specific region. If a QSA would like to conduct assessments in other regions, the company must pay additional fees for the other regions. The QSA cannot conduct assessments, however, unless individual employees of the company also complete the requisite training program, which costs approximately $3,000 per person. In addition, the QSA and all employees must pay hefty “requalification” fees every year in order to maintain their status as a PCI QSA.

A company that wants to serve as a QSA in the United States, and has a single employee trained to perform assessments, must pay at least $27,250 initially to the PCI SSC, and at least $13,650 every year thereafter. This cost is exhorbitant for smaller security firms, and any security firm engaged in PCI assessment work must price their services high enough to ensure that they recoup their annual QSA fees. The fees ultimately get passed along to the merchants and other entities that are required to hire a QSA.

In short, the QSA program is a money-making business. Over the years, the PCI SSC added additional “Assessors and Solutions” programs, such as “Approved Scanning Vendors,” “Payment Application-QSA” and “PCI Forensic Investigator” programs. Merchants and other entities are required by the card brands to utilize services and/or products of these assessors. Each of these programs requires additional application and training fees, which are paid to the PCI SSC, which in turn is owned by the five major card brands.

The good standing of a QSA can be revoked at any time by the PCI SSC, which can require QSAs to “requalify” or simply stop providing QSA services. Because of this, QSAs are beholden to the PCI SSC (and therefore the card brands) in order to remain in business as QSAs.

Since the card brands make money off the PCI compliance assessment program, they have a direct financial incentive to ensure that retailers and other entities continue to hire QSAs to conduct the assessments.

6.4.6 Fines

The QSA’s report can have extensive consequences for a retailer or payment processor. Gaps in PCI compliance can be expensive to correct and result in large fines levied against the noncompliant entity. In the event of a breach, the QSA’s report may even be used in court to demonstrate negligence, as we will see later.

Merchants or service providers can be hit with costly fines and penalties for noncompliance—but not by the card brands directly. Instead, the card brands have created a system in which they fine intermediary banks, and then fines and liabilities trickle down to merchants at the banks’ discretion.

The fines for noncompliance can be substantial—up to $200,000 per violation, according to the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules, which address account information security noncompliance for Visa.22 Fines for noncompliance in this case are paid to the card brand (in this case, Visa). Banks, of course, are in a much better position to pay these fines than a small mom-and-pop retailer. In the case of Cisero’s, Visa fined U.S. Bank, and then let U.S. Bank decide whether to go after the McCombs to recover the money.

22. USA Visa, Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules, https://usa.visa.com/dam/VCOM/download/about-visa/15-October-2014-Visa-Rules-Public.pdf (accessed April 23, 2016).

6.5 TJX Breach

On January 17, 2007, the TJX Companies announced, painfully, that it had “suffered an unauthorized intrusion into its computer systems that process and store information related to customer transactions. While TJX has specifically identified some customer information that has been stolen from its systems, the full extent of the theft and affected customers is not yet known.”23

23. TJX Companies, Inc. “The TJX Companies, Inc. Victimized by Computer Systems Intrusion; Provides Information to Help Protect Customers,” press release, January 17, 2007, https://www.doj.nh.gov/consumer/security-breaches/documents/tjx-20070117.pdf.

Initially, the company estimated that more than 45.6 million card numbers had been stolen over an 18-month period—the largest payment card data breach to have ever been publicly reported. That number was ultimately raised to more than 94 million breached payment card numbers. In addition, personal information such as driver’s license numbers and other details for 451,000 individuals was exposed; ironically, the information had been collected for the purposes of combating fraud.

Visa reported that losses due to fraud were as high as $83 million and climbing. “You know, these [card numbers] are going to be sold off for a period of time in the future, so it’s going to continue for some time out there,” said Joseph Majka, vice president of investigations and fraud management for VISA USA.24

24. Mark Jewell, “TJX Breach Could Top 94 Million Accounts,” NBC News, October 24, 2007, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/21454847/ns/technology_and_science-security/t/tjx-breach-could-top-million-accounts.

Banks, card brands, and TJX itself struggled to sort out the liability. The ensuing litigation established a strong precedent that demonstrated that merchants would be held accountable for losses due to payment card breaches. Even more important, it cemented the role of PCI compliance as a tool for determining who was at fault. By the time the dust had settled, the retailer’s lack of PCI compliance had been broadcast throughout the news, used as evidence in court, and even triggered new state laws. In the court of public opinion and law, PCI compliance mattered.

In this section, we will walk through the important precedents that the TJX case established for determining liability in payment card breaches.

6.5.1 Operation Get Rich or Die Tryin’

As payment technology largely stalled in the United States, and PCI compliance slowly gained traction, criminals were exploring innovative new ways to steal card numbers in bulk.

Following the success of Operation Firewall and the takedown of Shadowcrew (see Chapter 5), Albert Gonzalez moved to Miami, where he continued working as a salaried informant for the Secret Service. He provided agents with information about active carders and gave presentations about cybercrime. At one point, he even “shook the hand of the head of the Secret Service.”25

25. James Verini, “The Great Cyberheist,” New York Times Magazine, November 10, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/14/magazine/14Hacker-t.html.

At the same time, Albert was on a mission of his own—one that he dubbed “Operation Get Rich or Die Tryin’.” By late 2004, “war driving” (enumerating wireless networks while driving, for the purposes of hacking) had become popular. Albert was intrigued. While working for the Secret Service in Miami, he enlisted the help of some of his Internet Relay Chat (IRC) buddies and convinced them to drive around the Miami area, searching for retailers with vulnerable networks. They quickly found a Marshalls with a weak wireless access point, broke in, and gave Gonzalez remote access to the network as well. From there, the group wormed their way into the servers of TJX, Marshall’s parent company, and found a treasure trove of stored payment card data, which they siphoned out little by little.

6.5.2 Point-of-Sale Vulnerabilities

The initial card dumps from TJX weren’t good enough for Albert. Much of the card data had been stored for extended periods, and a large percentage of the cards had expired. Albert wanted fresh card data. He realized that the best place to get it was from the POS systems, where customers swiped their cards. These, too, were hackable.

Albert and his friends began walking around retailers in Miami, gathering information about makes and models of POS devices. One of his colleagues managed to swipe a POS device from the checkout counter of an OfficeMax in Los Angeles, to help their research. Overseas, one of his friends in Estonia hacked into Micros Systems, a POS manufacturer; stole a list of employee usernames and passwords; and sent it over. Albert convinced his old friend, programmer Stephen Watt (who worked at Morgan Stanley), to write a sniffer program for him. The program, which Watt reportedly dashed off quickly, sniffed network traffic and logged any credit card numbers that were sent unencrypted. Armed with default credentials, Albert and his cohorts installed the sniffer program on central POS servers in multiple major retailers and captured credit card numbers in real time just as they were sent to the server for processing.

6.5.3 Green Hat Enterprises

Albert had learned his lesson about the risks of cashing out. Instead of monetizing the card data himself, he forwarded the stolen data to a team of colleagues around the country and overseas, who would cash out and mail him his share. Albert made so much money he threw himself a $75,000 birthday party in Manhattan. He regularly received packages containing hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash, at one point complaining to a friend “that he had been forced to count $340,000 by hand because his money counter was broken from overuse.” (His friend responded with “several pages worth of LOLs.”)26

26. Sabrina Rubin Erdely, “Sex, Drugs, and the Biggest Cybercrime of All Time,” Rolling Stone, November 11, 2010, http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/sex-drugs-and-the-biggest-cybercrime-of-all-time-20101111.

Later, Albert sold the dumps to a Ukranian, Maksym Yastremskiy. Yastremskiy would sell the card numbers to buyers around the world and split the profits. “Yastremskiy arranged to have the payment data encoded onto bank cards, which were then sold at nightclubs all over the world for $300 a pop, of which Albert got half.”27 He also used services such as E-Gold and WebMoney to launder funds electronically.

27. Erdely, “Sex, Drugs.”

Before he knew it, Albert was running an international criminal carding syndicate. “No one I spoke with compared him to a gangster or a mercenary,” reported James Verini of the New York Times, years later, “but several likened him to a brilliant executive.” He dubbed his venture, “Green Hat Enterprises.”

When asked to compare Albert to other cybercriminals, Seth Kosto, an assistant U.S. attorney in New Jersey, replied: “As a leader? Unparalleled. Unparalleled in his ability to coordinate contacts and continents and expertise. Unparalleled in that he didn’t just get a hack done—he got a hack done, he got the exfiltration of the data done, he got the laundering of the funds done. He was a five-tool player.”28

28. Verini, “Great Cyberheist.”

Green Hat Enterprises was a smashing success. At the same time, card brands began to alert the retailers to the massive card thefts and pulled in law enforcement. Federal agents were searching for the ringleaders of the massive card fraud, unaware that the criminal mastermind was right under their noses, working as a Secret Service informant.

6.5.4 The New Poster Child

When TJX revealed the breach in January 2007, the public was shocked—not just by the breathtaking scale of the theft, but by how little TJX seemed to know about what was going on in its own network and by the company’s seemingly lackadaisical attitude toward security. “[T]he breach has made it something of a poster child for sloppy data security practices among retailers,” reported ComputerWorld.29

29. Jaikumar Vijayan, “One Year Later: Five Takeaways from the TJX Breach,” Computerworld, January 17, 2008, https://www.computerworld.com/article/2538711/cybercrime-hacking/one-year-later–five-takeaways-from-the-tjx-breach.html.

The breach was likely detected early by Citigroup, who identified TJX as a common point-of-purchase for a group of stolen card numbers. In other words, Citigroup would have found that a group of consumers whose card numbers were used fraudulently had all shopped at TJX stores.30 TJX received notification in July 2006, although the company did not discover its ongoing network intrusion until December of that year. By then, hackers had been raiding the company’s network for nearly a year and a half.

30. Jacqueline Bell, “Citigroup May Have Discovered Data Breach Early: TJX,” Law 360, December 6, 2007, https://www.law360.com/banking/articles/41795/citigroup-may-have-discovered-data-breach-early-tjx.

“TJX Failed to Notice Thieves Moving 80-Gbytes of Data on Its Network” screamed a headline in Wired magazine. Consumers were frustrated that, even after the company discovered the intrusion in December 2006, “it took the company another month to disclose the breach to consumers.”31 One forensic investigator reported that he had never seen such a “void of monitoring and capturing via logs activity” in a major retailer.

31. Kim Zetter, “TJX Failed to Notice Thieves Moving 80-Gbytes of Data on Its Network,” Wired, October 26, 2007, https://www.wired.com/2007/10/tjx-failed-to-n.

A month after the breach was announced, TJX was still unable to say just how many consumers were affected. “We don’t have a number for you there. Our work is not finished,” said a TJX spokesperson.32

32. Ellen Nakashima, “Customer Data Breach Began in 2005, TJX Says,” Washington Post, February 22, 2007, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/2007/02/22/customer-data-breach-began-in-2005-tjx-says/dcf4720f-6385-4e4e-9b9c-9b120a0eaef8/.

6.5.5 Who’s Liable?

Many banks reissued cards, an expensive process that cost up to $25 per card and irritated consumers. Hoping to recoup costs, hundreds of issuing banks represented by the Connecticut Bankers Association, Maine Association of Community Banks, and Massachusetts Bankers Association joined forces with Amerifirst and others to file a class-action lawsuit against TJX.

A key piece of the banks’ case against TJX was that the retailer “had not complied with nine of the 12 security controls mandated by the Payment Card Industry (PCI) data security standards when the breach occurred.”33 The Canadian privacy commissioner conducted an eight-month investigation that cited TJX’s PCI violations, which included lack of network segmentation, weak wireless security, and lack of proper logging.

33. Jaikumar Vijayan, “TJX Violated Nine of 12 PCI Controls at Time of Breach, Court Filings Say,” Computerworld, October 26, 2007, http://www.computerworld.com/article/2539588/security0/tjx-violated-nine-of-12-pci-controls-at-time-of-breach–court-filings-say.html.

TJX’s PCI compliance issues were seen by many as evidence that the company had been negligent in protecting sensitive consumer data. Never mind that PCI wasn’t a law and that Visa had given TJX an extension for meeting the new requirements. “Visa will suspend fines until Dec. 31, 2008, provided your merchant continues to diligently pursue remediation efforts,” Visa’s Joseph Majka had written in a December 2005 letter. “This suspension hinges upon Visa’s receipt of an update by June 30, 2006, confirming completion of stated milestones.”34

34. Ericka Chickowski, “TJX: Anatomy of a Massive Breach,” Baseline, January 30, 2008, http://www.baselinemag.com/c/a/Security/TJX-Anatomy-of-a-Massive-Breach.

After the fact, the TJX case established a precedent for using PCI compliance (or lack thereof) as evidence in data breach cases. If a merchant was breached and found to be noncompliant, banks and other entities that suffered losses could use noncompliance as evidence that the merchant was negligent, strengthening their case for compensation.

6.5.6 Struggles with Security

Why wasn’t TJX more secure? As with most retailers, it boiled down to cost and complexity.

In 2005, TJX’s chief information officer, Paul Butka, wrote a telling email to his staff when discussing whether to upgrade from the outdated WEP wireless encryption protocol—which was widely known to be weak—to the more secure WPA technology. “WPA is clearly best practice and may ultimately become a requirement for PCI compliance sometime in the future. I think we have an opportunity to defer some spending from FY07’s budget by removing the money for the WPA upgrade,” he wrote.

A few weeks later, another TJX staff member prophetically countered, “The absence of rotating keys in WEP means that we truly are not in compliance with the requirements of PCI. This becomes an issue if this fact becomes known and potentially exacerbates any findings should a breach be revealed.”35

35. Chickowski, “Anatomy of a Massive Breach.”

TJX was certainly not alone in its challenges. In a press release later, TJX said its security was “as good as or better than most other major U.S. retailers.” This was probably true.36

36. TJX Companies, “The TJX Companies, Inc. Announces Settlement with Attorneys General Regarding 2005/ 2006 Cyber Intrusion(s),” press release, June 23, 2009, http://investor.tjx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=118215&p=irolnewsArticle&ID=1301566.

“[L]arge companies with highly distributed, older computing environments can expect to have an especially hard time applying PCI security controls,”said Amer Deeba, an executive at Qualys. In order to become PCI compliant, retailers had to coordinate with the vendors of their POS systems, operating systems, and applications to ensure that all of the software that they relied upon was in compliance. They typically had to re-architect their networks and invest large amounts of money in software upgrades. In some cases, vendors would not or could not upgrade their software, leaving retailers with even bigger headaches. “Many of the big [retailers] are handling credit card information from all around the world and storing it in legacy systems that are no longer supported or updated by vendors.”37

37. Vijayan, “Retailers Take Swipe.”

After the eight-month investigation of TJX, the Canadian privacy commissioner concluded that “TJX[’s] experience illustrates how maintaining custody of large amounts of sensitive information can be a liability.”

“The lesson?” The Canadian government concluded, “One of the best safeguards a company can have is not to collect and retain unnecessary personal information. This case serves as a reminder to all organizations operating in Canada to carefully consider their purposes for collecting and retaining personal information and to safeguard accordingly.”38

38. Privacy Professor, “Canadian Privacy Commissioners Release TJX Investigation Report,” Privacy Guidance (blog), September 25, 2007, http://privacyguidance.com/blog/canadian-privacy-commissioners-release-tjx-investigation-report.

There are two ways to avoid data spills:

Carefully secure sensitive data.

Reduce or eliminate sensitive data.

You can’t spill hazardous data if it doesn’t exist.

6.5.7 TJX Settlements

For TJX, the breach was expensive—although the company bounced back. In August 2007, the company reported data breach response costs of $256 million. Researchers estimated the final cost would be closer to $500 million to $1 billion.39

39. Ross Kerber, “Cost of Data Breach at TJX Soars to $256m,” Boston.com, August 15, 2007, http://archive.boston.com/business/globe/articles/2007/08/15/cost_of_data_breach_at_tjx_soars_to_256m.

TJX settled the class-action lawsuits with issuers and consumers quickly, as follows:

Consumers: The consumer class action claimed that TJX was slow to notify customers of the breach, exposing people to identity theft without the ability to seek protection. The case was settled in September 2007, just nine months after the breach notification. “TJX will offer up to $7 million in store vouchers to customers who incurred out-of-pocket or lost time costs from the intrusion, and hold a one-time, three-day customer appreciation sale in which prices at TJX stores will be reduced by 15% for all customers. The vouchers, which are transferable and stackable, would range from $30-$60 per consumer based on documented evidence.”40

40. Ron Zapata, “TJX Settles Consumer Class Actions over Data Breach,” Law 360, September 24, 2007, https://www.law360.com/articles/35681/tjx-settles-consumer-class-actions-over-data-breach.

Issuers: Issuers claimed that TJX was negligent in securing payment card data—and had ample evidence to back that up. They primarily sought reimbursement for the steep costs of reissuing cards. During 2006, Visa had rolled out its new “Account Data Compromise Recovery” (ADCR) program that “provides automatic reimbursement to U.S. issuers for incremental counterfeit fraud losses from the theft of improperly stored card information.” However, Visa’s ADCR did not cover costs such as card reissuing. In late 2007, the issuers settled with TJX for $40.9 million. “It is expected that financial institutions will receive greater reimbursement by opting into the TJX settlement than they would have received under the traditional or ADCR programs,” commented Business Wire.41

41. “Visa and TJX Agree to Provide U.S. Issuers up to $40.9 Million for Data Breach Claims,” Business Wire, November 30, 2007, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20071130005355/en/Visa-TJX-Agree-Provide-U.S.-Issuers-40.9.

Forty-one state attorneys general also filed suit against TJX in the wake of the breach. Two years later, the case finally settled in a landmark agreement. According to the company’s press release, TJX agreed to:42

42. TJX Companies, “TJX Companies, Inc. Announces Settlement.”

Provide $2.5 million to establish a new Data Security Fund for use by the states to advance effective data security and technology

Provide a settlement amount of $5.5 million together with $1.75 million to cover expenses related to the states’ investigations

Certify that TJX’s computer system meets detailed data security requirements specified by the states

Encourage the development of new technologies to address systemic vulnerabilities in the U.S. payment card system

Notably, the settlement required TJX to implement specific security technologies, including upgrading its WEP-encrypted access points to WPA, using virtual private networks (VPNs) and installing antivirus software. Gartner analyst Avivah Litan criticized the technical stipulations, stating, “I think the AGs are better off focusing on disclosure rules and consumer protection than on security technology. . . . As soon as the government starts mandating or recommending technologies like end-to-end encryption, their mandates or recommendations will become out of date.”43

43. Jaikumar Vijayan, “TJX Reaches $9.75 Million Breach Settlement with 41 States,” Computerworld, June 24, 2009, https://www.computerworld.com/article/2525965/cybercrime-hacking/tjx-reaches–9-75-million-breach-settlement-with-41-states.html.

For retailers, the 2009 TJX attorneys general settlement was a wake-up call. One law firm issued a client news release, stating: “The TJX Settlement is a warning. All companies maintaining personal information . . . must implement a secure information protection program with regular auditing procedures.”44

44. Tara M. Desautels and John L. Nicholson, “TJ Maxx Settlement Requires Creation of Information Security Program and Funding of State Data Protection and Prosecution Efforts,” Pillsbury Law, July 1, 2009, https://www.pillsburylaw.com/images/content/2/6/v2/2626/7F4F43B367B5276B0CFA6D13CFF4044C.pdf.

Despite the legal turmoil and direct breach costs, for TJX, the damage wasn’t sustained. One commentator complained, “You’d think with such a heavily-publicized breach of personal information that people would be going out of their way to avoid shopping at TJX properties like TJ Maxx and Marshall’s. Nope. TJX is actually enjoying a healthy 8% increase in revenue over 2006 according to industry reports. . . . It’s no wonder so many companies are slow to take compliance initiatives around information security seriously.”45

45. Mark Tordoff, “TJX Settlement Shows Why Compliance Isn’t Taken Seriously,” Toolbox (blog), September 26, 2007, https://it.toolbox.com/blogs/mark-tordoff/tjx-settlement-shows-why-compliance-isnt-taken-seriously-092607.

6.5.8 Data Breach Legislation 2.0

The TJX breach generated a new wave of legislative activity, primarily designed to authorize third-party claims against breached vendors and establish security standards for payment card data. “In response to the public and industry concern data breaches have generated, legislators at the state level are rolling out ‘Data Breach Legislation 2.0,’” reported the International Association of Privacy Professionals, a year after the TJX breach was announced. “Further, legislators often are turning to the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (the PCI DSS) as the benchmark cybersecurity standard for these new statutes. . . . PCI allows legislators to side-step the need to become data security experts and, at the same time, adopt a standard that accounts for data security’s constantly changing nature.”46

46. Luis Salazar, “Data Breach Legislation 2.0,” IAPP, January 1, 2008, https://iapp.org/news/a/2008-01-data-breach-legislation-2.0.

Following the TJX breach, lawmakers in states including Minnesota, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, California, and Texas proposed new laws regarding payment card data security. Minnesota passed the Plastic Card Security Act shortly thereafter, based on a core PCI provision that disallowed storage of certain card data. Under the law, “any company that suffers a data breach and is found to have been storing prohibited card data on its systems will have to reimburse banks and credit unions the costs associated with blocking and reissuing cards. Such companies could also be subject to private action brought by individuals who might have been affected by a violation of the state law.”47 This law set the stage for additional lawsuits in subsequent data breaches, including the 2014 Target breach.

47. Jaikumar Vijayan, “Minnesota Becomes First State to Make Core PCI Requirement a Law,” Computerworld, May 23, 2007, http://www.computerworld.com/article/2541431/security0/minnesota-becomes-first-state-to-make-core-pci-requirement-a-law.html.

In the months that followed the TJX breach, card brands used the TJX case to push PCI compliance programs—and it worked. By October 2007, “Visa announced that 65 percent of level-one merchants and 43 percent of level-two merchants are compliant, up from 36 percent and 15 percent at the start of the year, respectively.”48 Merchants that did not comply were hit with fines.

48. Dan Kaplan, “TJX Settles with Banks over Data Breach,” SC Media, December 19, 2007, https://www.scmagazine.com/tjx-settles-with-banks-over-data-breach/article/554018.

Banks rallied behind “legislation that incorporates PCI DSS as a means of establishing retailer liability for data breaches, with the expectation that it will open the doorway to damage recoveries for them.”49 Texas very nearly became the first state to mandate that retailers comply with PCI DSS when the state House passed H.B. No. 3222 in 2007—but the bill died in Senate committee.

49. Salazar, “Data Breach Legislation 2.0.”

6.6 The Heartland Breach

In 2008, the Heartland breach became the largest payment card breach the world had ever seen, with 130 million card numbers stolen. Heartland, a payment processor based in Princeton, New Jersey, processed far more credit card numbers than any one merchant. The company acted as a middleman, receiving swiped card numbers from approximately 200,000 merchants and connecting them with the card networks. Heartland processed $66.9 billion dollars’ worth of transactions in 2008.

Unlike TJX, Heartland had been certified PCI compliant at the time of the breach. As a result, the Heartland breach raised important questions regarding the value of PCI compliance for proactively protecting payment card data.

In this section, we will discuss the Heartland case and the issues that it raised regarding PCI compliance. We will also study Heartland’s impressive response and show how the technologies it implemented following the breach moved the entire industry forward.

6.6.1 Heartland Gets Hacked

Albert Gonzalez was on top of the cybercriminal world. He was a millionaire who controlled an international cybercrime ring. But by day, he still worked for the Secret Service, and he hated the daily grind. He was constantly looking for new challenges—whether it was checking for vulnerabilities in POS systems at local retailers such as Toys R’ Us or surveying the area for weak wireless networks that he could hack. In late 2007, he teamed up with two Eastern European criminals to hack into payment processor Heartland Payment Systems, as well as 7-11, Hannaford Brothers, and other major retailers.50

50. United States v. Albert Gonzalez, 2009R00080 (D.N.J. 2009), https://www.wired.com/images_blogs/threatlevel/2009/08/gonzalez.pdf.

The hackers gained their foothold in the Heartland network during late December 2007. Leveraging a SQL injection vulnerability in an Internet-facing website, the criminals wormed their way into the network and installed a sniffer tool, capturing fresh payment card data as it was in transit across the network.

Visa alerted Heartland to “suspicious activity” in October 2008. Heartland reacted quickly, working closely with the card brands and pulling in multiple forensic investigators. When a breach was confirmed on January 12, 2009, they quickly reported it to the authorities. A week later, Heartland issued a press release along with customer support programs, such as a website for consumers.51

51. Heartland Payment Systems, “Heartland Payment Systems Uncovers Malicious Software In Its Processing System,” press release, January 20, 2009, http://web.archive.org/web/20090127041550/ http://2008breach.com/Information20090120.asp.

6.6.2 Retroactively Noncompliant

Heartland Payment Systems was PCI compliant—or so it thought. In April 2008, the company underwent its routine examination by a PCI QSA and was certified compliant. Nine months later, the company discovered that it had been hacked.

Then the lawsuits began. Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover all filed claims, in addition to issuing banks. Suddenly, in March 2009, Visa announced that Heartland was no longer considered a PCI compliant service provider. In fact, Visa’s chief enterprise risk officer, Ellen Richey, said that despite its QSA certification, the fact that Heartland was breached meant that it wasn’t PCI compliant in the first place. “As we’ve said before,” she continued, “no compromised entity has yet been found to be in compliance with PCI DSS at the time of a breach.”52

52. Jaikumar Vijayan, “Visa: Post-Breach Criticism of PCI Standard Misplaced,” CSO, March 20, 2009, https://www.cso.com.au/article/296278/visa.

Security professionals were floored. “What we see is that although no PCI-compliant company seems to ever get breached, many are certified and then found non-compliant after the breach,” said Rich Mogull, founder of Securiosis. “Thus, it’s clear the certification process is flawed. While I don’t expect certification to impart immunity from attack, decertifying all these companies seems disingenuous.”53

53. Dan Kaplan, “Visa: Heartland, RBS WorldPay No Longer PCI Compliant,” SC Media, March 13, 2009, https://www.scmagazine.com/visa-heartland-rbs-worldpay-no-longer-pci-compliant/article/555578.

Many questioned the value of the PCI standards, an opinion that Visa executives dismissed as “premature.” Others pointed out that Visa’s claim that Heartland was retroactively noncom-pliant could be “an attempt by the credit card company to protect itself legally and prevent the payment processors from using PCI as a shield against breach-related lawsuits filed by banks and credit unions.”54

54. Vijayan, “Visa: Post-Breach Criticism.”

Heartland executives emphasized that their network had been examined in detail by PCI QSAs, none of whom identified the vulnerability that was exploited by the hackers. Furthermore, after the breach Heartland was required to hire a PCI Qualified Incident Response Assessor (at its own expense), to identify the source of the compromise—an investigation that took six weeks.

6.6.3 Settlements

Ultimately, Heartland settled with Visa for $60 million, Mastercard for $41.1 million, American Express for $3.6 million, and Discover for $5 million. The company also settled a consumer class-action lawsuit by establishing a $2.4 million fund for consumer claims.55

55. Penny Crosman, “Heartland and Discover Agree to $5 Million Data Breach Settlement,” Bank Systems & Technology, September 3, 2010, http://www.banktech.com/payments/heartland-and-discover-agree-to-$5-million-data-breach-settlement/d/d-id/1294095?.

Industry expert Avivah Litan called the settlements fair and reasonable, noting that the card brands’ response to breaches had matured. “Visa and its member banks have much more experience with breaches now than they did when the TJX breach hit,” she said. “They know how to settle these matters more amicably.” Indeed, despite the fact that the Heartland breach affected far more cardholders, their overall costs were estimated to be far less than the $250 million that TJX had set aside. According to Litan, this was due in part to Heartland CEO Bob Carr’s “collegial spirit” and productive working relationship with the card brands, which helped the company avoid “endless litigation.”56

56. Linda McGlasson, “Heartland, Visa Announce $60 Million Settlement,” Bank Info Security, January 8, 2010, http://www.bankinfosecurity.com/heartland-visa-announce-60-million-settlement-a-2054.

6.6.4 Making Lemonade: Heartland Secure

Unlike most merchants, Heartland was in a unique position to change the industry after experiencing its breach. As the fifth-largest merchant acquirer in the United States, it held significant market share. After the breach, Heartland’s team conducted an analysis and identified a key area of weakness: the interception of sensitive data in transit across networks within the payment system. Theft of payment card data had been rampant for years, but the theft of data in transit across the network was a relatively new method used by criminals, notably emerging in the spotlight during the Hannaford breach of 2008 (also perpetrated by Albert Gonzalez).

According to CEO Bob Carr, Heartland considered three possible solutions for securing payment card data throughout the network:59

59. Julia S. Cheney, Heartland Payment Systems: Lessons Learned from a Data Breach, (discussion paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, January 2010), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/consumer-finance-institute/payment-cards-center/publications/discussion-papers/2010/d-2010-january-heartland-payment-systems.pdf.

End-to-end encryption, in which the payment card data is encrypted from the point where it is swiped all the way throughout the network, including both while it is in transit and in storage.

Tokenization, where the credit card numbers are replaced with randomly generated strings (“tokens”) after they are swiped, so that merchants and other entities do not have to store actual card data to reference in the event of disputes.

Chip (EMV) technology, where each card contains a “smart” microchip that can be used to facilitate encrypted data exchange, rather than relying on a simple magnetic stripe.

Of these three, Heartland prioritized the deployment of end-to-end encryption as a means of securing data in transit. Carr “emphasized that Heartland’s end-to-end encryption model positioned Heartland to secure much of this process . . . using its own resources; only [a fraction] required cooperation from the card brand networks.”60

60. Cheney, Heartland Payment Systems.

To implement the end-to-end encryption model, Heartland worked with a POS development partner to design the Heartland E3 Encrypting Payment Device. This POS terminal encrypted PINs using hardware (TPM) chips within the device and transmitted the data to the payment processor, which held the corresponding keys. The devices were more expensive than a typical POS system (selling for $300 to $500 at the time), but Carr pointed out that merchants had to weigh these costs against PCI compliance requirements and associated risks.61

61. Cheney, Heartland Payment Systems.

Eventually, Heartland rolled out the Heartland Secure program, which combined the E3 end-to-end encryption solution, EMV (“chip”) card support, and tokenization technology. By 2015, Heartland was so confident in the security of its new system that it offered the world’s first Merchant Breach Warranty for Heartland Secure merchants: “If the encryption fails on a Heartland Secure machine, Heartland will reimburse the merchant for the amount of compliance fines, fees and/or assessments the merchant must pay to the card brands, issuing banks and acquiring bank(s).”62

62. “Heartland First to Offer Comprehensive Merchant Breach Warranty,” Business Wire, January 12, 2015, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150112005260/en/Heartland-Offer-Comprehensive-Merchant-Breach-Warranty.

Michael English, Heartland’s executive director of product development, cut to the chase: “Through encryption and tokenization, a merchant eliminates clear text card data so if their network is breached, there is no card data to steal and monetize.”63 Although Heartland’s breach was devastating in the short term, the company’s reaction spurred the deployment of new technologies and increased security throughout the payment ecosystem.

63. “Heartland First to Offer.”

6.7 PCI and Data Breach Investigations

Over time, more and more retailers became PCI compliant—and continued to get hacked. In court, merchants sought to use documentation of PCI compliance as a defense against card brands’ fines and litigation. The card brands, in turn, had every incentive to prove that merchants were not actually PCI compliant, even after the fact—and they had the upper hand. In this section, we will show how the card brands stacked the deck against merchants with respect to data breach investigations and discuss how attorney-client privilege can provide protection for parties involved in postbreach litigation.

6.7.1 PCI Forensic Investigators

The PCI SSC established the role of the PCI Forensic Investigator (PFI), which investigates a merchant, collects evidence, and provides a full report to the card brands. Based on their contracts, card brands can require merchants to have a forensic investigation conducted, at the merchant’s expense.64 The merchant must select a PFI from a short list of approved vendors.

64. PCI Security Standards Council, Forensic Investigator FAQ, https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/documents/PCI_Forensic_Investigator_FAQ.pdf (accessed January 12, 2018).

At the time of this writing, there are 20 approved PFIs that serve the U.S. region. In order to become a PFI serving the United States, a firm must pay the PCI SSC a fee of $27,500 to “qualify,” in addition to fees for training specific employees.

Hiring a PFI, however, is not like hiring a truly independent forensic investigator (despite the fact that the PCI SSC says “PFIs are required to uphold strict independence requirements”). PFIs must be QSAs, first and foremost. They have specific contractual obligations to the PCI SSC. However, they cannot be the same QSA that operates as the merchant’s QSA because, according to the PCI SSC, “they would be potentially investigating their own work.”

The “independence” largely ends there. Importantly, PFIs are contractually obligated to:

Ensure that potential evidence is acquired in a forensically sound manner and “could be used in [a] court of law.”65