Chapter 9. Health Data Breaches

Imagine if a photograph from your medical record was tweeted out onto the Internet, revealing your latest medical problem to everyone in the world. That’s exactly what happened to NFL football player Jason Pierre-Paul after he injured his right hand in a fireworks accident.

After ESPN journalist Adam Schefter received a photograph of Pierre-Paul’s hospital chart, he tweeted: “ESPN obtained medical charts that show Giants DE Jason Pierre-Paul had right index finger amputated today.” The corresponding photos showed the operating room schedule and an excerpt of Pierre-Paul’s medical record from Miami’s Jackson Memorial Hospital.1

1. Matt Bonesteel, “Jason Pierre-Paul, Adam Schefter and HIPAA: What It all Means,” Washington Post, July 9, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/early-lead/wp/2015/07/09/jason-pierre-paul-adam-schefter-and-hipaa-what-it-all-means.

Pierre-Paul’s team was unaware of his amputation until ESPN’s tweet. Rumors of Pierre-Paul’s accident and hand injury had been circulating for days, and as a result the New York Giants had retracted its offer of a long-term $60 million contract.

After the tweet with Pierre-Paul’s medical record, a media storm ensued, with fans and journalists alike questioning the ethics—and legality—of Schefter’s decision to publish the photographs.2 Suddenly, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was trending. Fans posted angry messages accusing Schefter of violating the federal law:3

2. Erik Wemple, “Twitter Stupidly Freaks about ESPN, Jason Pierre-Paul and HIPAA,” Washington Post, July 9, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/erik-wemple/wp/2015/07/09/twitter-stupidly-freaks-out-about-espn-jason-pierre-paul-and-hipaa.

3. Eliot Shorr-Parks, “Did ESPN Violate HIPAA Rules by Posting Jason Pierre-Paul’s Medical Records?” NJ.com, July 8, 2015, http://www.nj.com/giants/index.ssf/2015/07/did_espn_violate_hippa_rules_by_posting_jason_pier.html.

“@AdamSchefter WHAT are you doing with someone’s confidential medical records? HIPAA might suggest you and @espn broke the law. #JPP #toofar”—Dane Oldridge (@TheREALCrankie1) July 9, 2015

“@adamschefter Dumb move man. You better get your blog ready because you’re not going to be on ESPN much longer. #HIPAA #Violation”—Aaron Stanley King (@trendoid) July 9, 2015

9.1 The Public vs. the Patient

Was Schefter’s tweet a HIPAA violation?

For Jackson Memorial Hospital, the incident was almost certainly a HIPAA violation. HIPAA protects the privacy and security of protected health information (PHI). The ground-breaking federal legislation was passed in 1996, and subsequently the HIPAA Privacy Rule and HIPAA Security Rule were issued, with compliance dates of 2003 and 2005, respectively. HIPAA has dramatically improved the security and confidentiality of PHI held by “covered entities”: heathcare providers, health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, as well as their “business associates” (people or organizations that work on behalf of a covered entity).

Jackson Health System took quick action. Chief Executive Officer Carlos A. Migoya immediately released an open letter stating: “[M]edia reports surfaced purportedly showing a Jackson Memorial Hospital patient’s protected health information, suggesting it was leaked by an employee. An aggressive internal investigation . . . is underway. . . . If we confirm Jackson employees or physicians violated a patient’s legal right to privacy, they will be held accountable, up to and including possible termination.”4

4. Jackson Health Systems (@jacksonhealth), “This is a Statement from Carlos A. Migoya, President and CEO of Jackson Health System in Regards to Current Events,” Twitter, July 9, 2015, 12:01 p.m., https://twitter.com/jacksonhealth/status/619219877518290951/photo/1.

9.1.1 Gaps in Protection

Yet Schefter and ESPN actually hadn’t violated the federal law. “HIPAA doesn’t apply to media who obtain medical records of others,” said Michael McCann, legal analyst for Sports Illustrated. “Invasion of privacy does, but 1st Amendment offers a good legal defense”—particularly in cases involving public figures.

HIPAA’s protections are limited—more so than most people realize. HIPAA and its cousin, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, are “downstream” data protection models, as described by Nicolas P. Terry, executive director of the Center for Law at Indiana University. “[W]hile upstream data protection models limit data collection, downstream models primarily limit data distribution after collection,” writes Terry.5 HIPAA/HITECH apply specifically to “covered entities” involved in the treatment and payment for healthcare services. They extend by contract to these entities’ “business associates.” The data by itself is not protected. Once health information escapes the confines of this very specific list of organizations—say, because of a data breach—there is little a patient can do to stop others from buying, selling, trading, or using it.

5. Nicholas P. Terry, “Big Data Proxies and Health Privacy Exceptionalism,” Health Matrix 24 (2014): 66.

In Florida, Pierre-Paul sued ESPN and Schefter, citing violations of the Florida medical privacy statute. However, the defendents pointed out that “Florida’s medical privacy law does not apply to the general public, including members of the media—it does not, as Plaintiff contends, essentially impose a world-wide prior restraint on the speech of any person who allegedly learns some medical information from a Florida-based health care provider.”6 The district court concurred.

6. Jason Pierre-Paul v. ESPN, Inc, No. 1:16-cv-2156 (S.D. Fla. 2016), http://thesportsesquires.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/307369385-Espn-s-Finger.pdf.

Pierre-Paul himself knew better than to accuse Schefter and ESPN of inappropriately reporting the fact of his amputation, proactively acknowledging that the information may have been “of legitimate public concern.” However, he alleged that “the Chart itself was not,” and that the publication of the actual photo from his medical record was an invasion of privacy.

“If the hospitalization of a public figure constituted authorization for the publication of that person’s medical records, then the right to privacy would be non-existent,” wrote Pierre-Paul’s legal team in court documents. “Indeed, public figures would hesitate to seek medical treatment, or be less likely to share certain information with health care professionals, out of fear that hospital personnel would sell their medical records to those who want to profit from the publication thereof (as ESPN did here), thereby negatively impacting their health.” Ultimately, Pierre-Paul and ESPN settled out of court, leaving several questions from their case unresolved.

9.1.2 Data Breach Perspectives

For Jackson Memorial Hospital, the Pierre-Paul disclosure was shameful, illegal, and cost two employees their jobs. For Schefter, tweeting Pierre-Paul’s medical information was considered by many to be accurate, timely, and relevant journalism—particularly given the importance of Pierre-Paul’s medical condition to his high-profile, public role. Regarding the photo of Pierre-Paul’s medical chart, Schefter said, “[I]n a day and age in which pictures and videos tell stories and confirm facts, in which sources and their motives are routinely questioned . . . this was the ultimate supporting proof.”7

7. Kevin Draper, “Jason Pierre-Paul Is Suing ESPN Because Its Reporting Was Too Accurate,” Deadspin, September 8, 2016, https://deadspin.com/jason-pierre-paul-is-suing-espn-because-its-reporting-w-1785963477.

In other words, the definition of a “data breach,” and the repercussions that follow, depend not just on what specific data was leaked but where it came from and how it came to be disclosed. Typically, there is a path of disclosure along which successive custodians—some authorized, some not—obtain and transfer protected data. In many cases, the path looks more like a tree because a single custodian may transfer the data to many others.

The question of who is an authorized or unauthorized custodian is tricky. A hospital might consider a third-party IT provider to be an authorized custodian, even though a patient might object. In some cases, the good of the public or a third party might outweigh the importance of the data subject’s privacy. The law often differs from the expectations of individuals along the path. As we will see, as data gets passed along, it can often seem like a game of telephone, where each data custodian imposes slightly different rules on the next party, and no one truly seems to be in control.

This has strange and confusing implications for data breach management. The same data may be exposed by two different organizations, but because they each have different relationships with the data subject, one is a data breach and one is not (as in the case of Jason Pierre-Paul, Jackson Memorial Hospital, and ESPN). Responders need to carefully consider not just how to respond to a data breach but whether a specific event “counts” as a data breach at all. When it comes to health information, this has become a very complicated question.

In this chapter, we’ll begin by covering the digitization of health information, which has paved the way for an increasing number of data breaches. We’ll touch on relevant parts of the HIPAA/HITECH regulations, which define prevention and response requirements for certain types of health-related breaches. (For simplicity, the discussion in this chapter is focused primarily on the U.S. HIPAA/HITECH laws, but many of the same issues apply to health data protection regulations in other jurisdictions.)

Later in this chapter, we’ll discuss the way data can escape from HIPAA/HITECH regulation or bypass it in the first place. We’ll analyze challenges specific to the healthcare environment that contribute to the risk of data breaches, including complexity, vendor-managed equipment, a mobile workforce, and the emergence of the cloud. Finally, we’ll enumerate the negative impacts of a breach and show how lessons learned from handling medical errors can help us resolve data breaches, too.

9.2 Bulls-Eye on Healthcare

In 2017 alone, 5 million medical/healthcare records were breached, according to the Identity Theft Resource Center’s (ITRC) data breach report.8 In 2015, that number was a whopping 121.6 million, thanks to megabreaches in the health sector, such as the Anthem and Premera cases.9

8. Identity Theft Resource Center, 2017 End of Year Report (San Diego: ITRC, 2018), https://www.idtheftcenter.org/images/breach/2017Breaches/2017AnnualDataBreachYearEndReview.pdf.

9. Identity Theft Resource Center, Data Breach Reports: December 29, 2015 (San Diego: ITRC, 2015), http://www.idtheftcenter.org/images/breach/DataBreachReports_2015.pdf.

“[S]ince late 2009, the medical information of more than 155 million American citizens has been exposed without their permission through about 1,500 breach incidents,” reported the Brookings Center for Technology Innovation.10

10. Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings, Hackers, Phishers, and Disappearing Thumb Drives: Lessons Learned from Major Health Care Data Breaches (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, May 2016), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Patient-Privacy504v3.pdf.

That means that nearly half of all Americans may have had their protected health information exposed—and this is only based on incidents that were actually detected and reported to the U.S. government.

Why are healthcare entities and business associates so commonly breached? The health industry has seen enormous changes in all five of the data breach risk categories: liquidity, access, retention, value, and proliferation. As we will see, a push to extract value from personal health information in bulk has dramatically increased the risk of data breaches—and created critical questions about what constitutes a “breach” in the first place.

9.2.1 Data Smorgasbord

Healthcare organizations store almost every kind of sensitive information imaginable: Social Security numbers (SSNs), billing data, credit card numbers, driver’s license numbers (and often high-resolution scans of IDs), insurance details, and, of course, medical records. In fact, healthcare providers are an excellent source of “fullz” (see § 5.3.1) since they tend to store a wide range of identification information, financial data, and contact details all in one place.

“The medical record is the most comprehensive record about the identity of a person that exists today,” says Robert Lord, founder of Protenus, which offers privacy monitoring software for healthcare organizations.11

11. Mariya Yao, “Your Electronic Medical Records Could Be Worth $1000 to Hackers,” Forbes, April 14, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/mariyayao/2017/04/14/your-electronic-medical-records-can-be-worth-1000-to-hackers/#4be095ad1856.

Criminals can split up the information contained within medical records and sell different pieces separately. For example, “[o]n the underground market forum AlphaBay, the user Oldgollum sold 40,000 medical records for $500 but specifically removed the financial data, which was sold separately,” reported McAfee Labs in 2016. “Oldgollum is essentially double-dipping to get the most from both markets.” McAfee’s team pointed out that the price of medical data is “highly variable,” in part because sellers can break up stolen data and sell the pieces for different purposes.12

12. C. Beek, C. McFarland, and R. Samani, Health Warning: Cyberattacks are Targeting the Health Care Industry (Santa Clara: McAfee, 2016), https://www.mcafee.com/us/resources/reports/rp-health-warning.pdf.

When the health insurance giant Anthem reported a breach of 78.8 million records in 2015, the stolen data included “names, birthdays, social security numbers, street addresses, email addresses and employment information, including income data.” Anthem was careful to report that no evidence indicated that “medical information such as claims, test results, or diagnostic codes were targeted or obtained.”13 Even so, the company was hit with a record $115 million settlement for the ensuing class-action lawsuit. The settlement fund was established to cover costs of credit monitoring and out-of-pocket expenses for victims.14

13. Anthem, “Statement Regarding Cyber Attack against Anthem,” press release, February 5, 2015, https://www.anthem.com/press/wisconsin/statement-regarding-cyber-attack-against-anthem.

14. Beth Jones Sanborn, “Landmark $115 Million Settlement Reached in Anthem Data Breach Suit, Consumers Could Feel Sting,” Healthcare IT News, June 27, 2017, http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/landmark-115-million-settlement-reached-anthem-data-breach-suit-consumers-could-feel-sting.

Anthem is a prime example that illustrates how healthcare providers and business associates are on the hook not just for potential breach of health data, but also the identification and financial data that is typically bundled with it.

Due to the volume and value of the data that healthcare providers hold, they must contend with many of the same risks as financial institutions and government agencies—plus, they carry the additional risk of handling extensive volumes of personal health data.

9.2.2 A Push for Liquidity

Health data has become increasingly “liquid,” stored in compact, structured formats that facilitate transfer and analysis. Once upon a time, healthcare providers stored your information in filing cabinets and accessed it when needed for treatment purposes. Now your data has been converted to electronic bits and bytes.

In the past two decades, healthcare has witnessed a technology revolution. Today, health-care providers’ computer systems are increasingly interconnected; many people have access to health-related data for purposes of treatment, cost/risk analysis, or medical research. Data is copied over and over, scattered throughout the world, often without the knowledge of the care provider, let alone the patient.

The digitization of personal health data and widespread adoption of electronic medical record (EMR) systems set the stage for large health data breaches. In 2009, the U.S. government passed the HITECH Act, which provided strong financial incentives for shifting to electronic systems. Beginning on January 1, 2015, healthcare providers were required to demonstrate “meaningful use” of EMR systems in order to maintain their Medicare reimbursement levels. As a result, many clinics rushed to transition from paper to electronic records in order to meet deadlines—and overlooked security.

When the HITECH Act passed, technology advocates celebrated, saying that electronic health records could save “tens of billions of dollars each year from reduced paperwork, faster communication and the prevention of harmful drug interactions.” Data mining could also lead to better decision making and treatment.15

15. Robert O’Harrow Jr., “The Machinery Behind Health-Care Reform,” Washington Post, May 16, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/15/AR2009051503667.html.

“Finally, we’re going to have access to millions and millions of patient records online,” said Harvard professor and physician Blackford Middleton—a statement that undoubtedly sent chills down the spine of any cybersecurity professional who read his quote in the Washington Post.16 Nearly a decade later, the digitization of health records has spurred the development of groundbreaking healthcare technologies—and eroded the privacy of hundreds of millions of data breach victims.

16. O’Harrow, “Machinery Behind Health-Care Reform.”

9.2.3 Retention

Medical records stick around. While there are no universal guidelines for medical record retention, most states have a minimum retention requirement of five to ten years.17 It is safe to say, however, with the conversion from paper to electronic format, many care providers have little incentive to clean out their file repositories. Indeed, with the emergence of the big data analytics industry, many organizations retain personal health data indefinitely since it can be sold or traded for valuable goods and services.

17. Health Information & the Law, Medical Record Retention Required Health Care Providers: 50 State Comparison, accessed January 17, 2018, http://www.healthinfolaw.org/comparative-analysis/medical-record-retention-required-health-care-providers-50-state-comparison.

9.2.4 A Long Shelf Life

Stolen health data can be useful for years after a breach—even a lifetime. “The value of a medical record endures far beyond that of a card,” says Douville. So can the harm, as illustrated by the case of “Frances.”

“PPL WORLD WIDE,” announced a Facebook post in January 2014. “FRANCES . . . IS HPV POSITIVE!” The posting included Frances’s full name and date of birth, “along with the revelation that she had human papillomavirus, a sexually transmitted disease that can cause genital warts and cancer,” reported NPR. “It also . . . ended with a plea to friends: ‘PLZ HELP EXPOSE THIS HOE!’”18

18. Charles Ornstein, “Small Violations of Medical Privacy Can Hurt Patients and Erode Trust,” NPR, December 10, 2015, http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/12/10/459091273/small-violations-of-medical-privacy-can-hurt-patients-and-corrode-trust.

Poor Frances had been treated at a local hospital, where a technician who knew her had access to her record and posted her diagnosis on Facebook. After Frances reported the incident to the nursing supervisor, the hospital sent her a letter of apology. But for Frances, the damage was done: “It’s hard to even still deal with it,” she said. “I’ll spend that extra gas money to go into another city to do grocery shopping or stuff like that, just so I don’t have to see anybody from around the neighborhood.”19

19. Ornstein, “Small Violations.”

Once stolen, health information can’t be changed or quickly devalued like other forms of data. You can change your payment card number after a data breach, but you can’t change your medical records.

In short, a data breach involving personal health information can come back to haunt patients for their entire lives.

9.3 HIPAA: Momentous and Flawed

In the United States, data breach prevention and response is regulated by federal law, at least when it comes to PHI. The HIPAA regulations include proactive cybersecurity requirements, while the HITECH Act (which was enacted many years later) specifically address breach response and notification. HIPAA/HITECH are among the few existing federal regulations that address cybersecurity and data breach response at a national level in the United States.

The HIPAA/HITECH regulations are far from perfect. Even for security professionals, understanding the requirements—let alone complying with them—can be a daunting challenge. In this section, we will show how HIPAA emerged and developed, in order to understand the original intent (and how that led to many of the “gaps” in HIPAA/HITECH coverage later on). Then, we will discuss the passage of the Breach Notification Rule and show how the implementation of fines and penalties led to increased breach reporting.

9.3.1 Protecting Personal Health Data

Our instinct to protect the privacy of health information goes back to the very founding of Western medicine. For more than two thousand years, physicians have sworn to keep patient health information secret. The earliest versions of the Hippocratic Oath included the line:

“Whatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.”20

20. Michael North trans., “The Hippocratic Oath,” National Library of Medicine, 2002, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greekoath.html.

The obligation to protect patient confidentiality remains today and is explicitly included in the AMA Code of Medical Ethics and similar documents used by medical schools.

At the same time, personal health information can be valuable for researchers, employers, and society at large—as well as media outlets, data brokers, and businesses seeking to make a profit. Greater connection and access to medical records can lead to better treatment for patients, but it has also introduced grave privacy concerns.

In 1997, the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Donna E. Shalala, gave an impassioned—and timely—speech at a National Press Club luncheon:21

21. “Health Care Privacy,” C-SPAN video, 53:05 min, posted, July 31, 1997, https://www.c-span.org/video/?88794-1/health-care-privacy&start=1629.

Until recently, at a Boston-based HMO, every single clinical employee could tap into patients’ computer records and see detailed notes from psycho-therapy sessions. In Colorado, a medical student copied countless health records at night and sold them to medical malpractice attorneys looking to win easy cases. And, in a major American city, a local newspaper published information about a congressional candidate’s attempted suicide. Information she thought was safe and private at a local hospital. She was wrong.

What about the rest of us? When we give a physician or health insurance company precious information about our mood or motherhood, money or medication, what happens to it? As it zips from computer to computer, from doctor to hospital, who can see it? Who protects it? What happens if they don’t?

. . . We are at a decision point. Depending on what we do over the next months, these revolutions in health care, communications, and biology could bring us great promise or even greater peril. The choice is ours. We must ask ourselves, will we harness these revolutions to improve, not impede, our health care? Will we harness them to safeguard, not sacrifice, our privacy? And will we harness these revolutions to strengthen, not strain, the very life blood of our health care system, the bond of trust between a patient and a doctor?

The fundamental question before us is: Will our health records be used to heal us or reveal us? The American people want to know. As a nation, we must decide.

Secretary Shalala presented recommendations for protecting healthcare information, which were based upon five key principles:

Boundaries: Health information should be used for health purposes, with a few carefully controlled exceptions.

Security: Entities that create, store, process, or transmit health information should take “reasonable steps to safeguard it” and ensure it is not “used improperly.”22

22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Testimony of Secretary of Health and Human Services, September 11, 1997,” ASPE, February 1, 1998, https://aspe.hhs.gov/testimony-secretary-health-and-human-services-september-11-1997.

Consumer Control: Individuals should have access to their personal health records, including the ability to review the content and access records, and the ability to correct any errors.

Accountability: Entities that misuse or fail to properly safeguard personal health information should be held accountable, through “real and severe penalties for violations . . . including fines and imprisonment.”

Public Responsibility: Personal health information can and should be disclosed in a controlled manner for the purposes of public health, research, and law enforcement purposes.

The balance between security and public disclosure has been particularly tricky, as we will see in the sections on deidentification and reidentification.

Ultimately, due to the efforts of Secretary Shalala and many others, the HIPAA Security Rule and Privacy Rule were issued and became the foundation for health information security, privacy, and breach response in the United States.

9.3.2 HIPAA Had “No Teeth”

The HIPAA Security Rule went into effect on April 1, 2005 (or a year later for smaller entities). It required all covered entities to establish administrative, technical, and physical controls designed to safeguard the security of PHI. This sounded good, but in practice, HIPAA was not effectively enforced. Moreover, it carried no requirement to notify affected persons in the event of a data breach. As a result, healthcare breaches were common but rarely reported or even discussed outside tight-knit information security circles.

In this section, we’ll discuss the impact of HIPAA on data breach preparation and response, from the period between 2005 and 2009 (prior to the implementation of the HITECH Breach Notification Rule). This will set the stage for discussing the impacts of the rule in the next section.

9.3.2.1 Lack of Enforcement

“Even though over 19,420 HIPAA complaints/violations have been officially lodged since HIPAA went into effect, it has resulted in zero fines,” reported Roger A. Grimes of InfoWorld in 2006. “This is amazing, but unfortunately, not surprising. Other than two criminal prosecutions on specific individuals, there appears to be no penalties for organizations violating the HIPAA Act.”23

23. Roger A. Grimes, “HIPAA has No Teeth,” CSO, June 5, 2006, http://www.infoworld.com/article/2641625/security/hipaa-has-no-teeth.html.

Security and privacy professionals around the country began to say that HIPAA had “no teeth.” Even if HHS were to impose a fine for a HIPAA violation, the penalties were fairly low, ranging from $100 to a maximum of $25,000 per calendar year for all violations “of an identical requirement or prohibition.”24 Many executives of healthcare organizations saw the potential fines as significantly less than the funds required to bring a healthcare facility’s network and processes in compliance with HIPAA.

24. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “HIPAA Administrative Simplification: Enforcement,” 70 Fed. Reg. 8389 (Feb. 16, 2006), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2006/02/16/06-1376/hipaa-administrative-simplification-enforcement.

9.3.2.2 No Breach Notification Requirement

The HIPAA Security Rule did not include any reference to the term “breach.” Although the term appeared in the proposed rule, the authors removed it in favor of the more general term “security incident,” defined as “the attempted or successful unauthorized access, use, disclosure, modification, or destruction of information or interference with system operations in an information system.”

Covered entities were required by law to “[i]dentify and respond to suspected or known security incidents; mitigate, to the extent practicable, harmful effects of security incidents that are known to the covered entity; and document security incidents and their outcomes.” Seem a little vague? Before the rule was finalized, commenters wrote in to request more specific guidance from HHS, but the authors responded that the details would be “dependent upon an entity’s environment and the information involved.”25

25. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “45 CFR Parts 160, 162, and 164: Subpart-C,” 68 Fed. Reg. 8377 (Feb. 20, 2003), https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Regulations-and-Policies/QuarterlyProviderUpdates/Downloads/cms0049f.pdf.

There was little pressure to report health data breaches, even to parties that could be affected. HIPAA did not include an explicit notification requirement. Instead, “[w]hen an improper disclosure (a ‘breach’) occurred, the responsible party [was] required to take available steps to ‘mitigate’ the harm of disclosure, which may mean notifying the individual whose information was disclosed.”26

26. Frost Brown Todd LLC, “HIPAA Breach Notification Rules,” October 6, 2009, https://www.frostbrowntodd.com/resources-New_HIPAA_Breach_Notification_Rules_10-06-2009.html.

There was no federal requirement to report breaches to any authority or to the public. This made it difficult for even the HHS to evaluate the extent of the problem. “There is no national registry of data breaches that captures all data breaches,” noted HHS in 2009. Since healthcare organizations also stored sensitive personal information such as SSNs, they were sometimes required to notify affected persons due to a breach of personal information under state laws. Some health data breaches were also reported to state health agencies under state law; many were tracked by public websites such as the Data Loss database maintained by the Open Security Foundation, which (surprisingly) HHS itself turned to for statistics.27

27. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Breach Notification for Unsecured Protected Health Information,” 74 Fed. Reg. 42739, 42761 (Aug. 24, 2009), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2009-08-24/html/E9-20169.htm.

9.3.2.3 Lack of Detection

Security incidents could lead to only more work, liability, angry patients, and possibily fines—so no one wanted to uncover one. When healthcare entities discovered a “security incident,” typically legal and compliance advisors would ask whether there was any evidence that PHI or other regulated data was accessed or acquired. If no evidence existed, then more often than not, no one would be notified and the incident would not be classified as a breach.

For example, if a system administrator detected that attackers had broken into a hospital server through an unpatched web interface, but the hospital did not retain file access logs or network logs that would indicate that sensitive data had (or had not) been touched, typically the legal team would conclude that there was no clear evidence of a breach, and it would not be reported to anyone. Case closed.

As a result, healthcare organizations had little incentive to invest in cutting-edge intrusion detection systems (IDS), detailed logging systems, or other advanced network monitoring technologies. Absent evidence, they usually assumed a breach had not occurred.

Practically speaking, in the early days of the HIPAA Security Rule, ignorance was bliss.

9.3.2.4 Lack of Economic Incentive

Even when word did get out about a healthcare data breach, there was little chance of it impacting a healthcare clinic’s bottom line.

“Patients are unlikely to change their doctor if they are impacted by a data breach,” wrote Niam Yaraghi of the Brookings Institution. “Most people choose their health care provider based on proximity to their residence. There is a limited supply of such providers in a given geographical area. In many instances, there is only one specialist, testing center, or hospital within miles of a patient’s home. The scarcity of specialized medical services means most patients have no choice. In a market where such major security breaches have little to no effect on the revenue stream of the organizations, there is no economic incentive to invest in digital security and prevent a data breach.”28

28. Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings, Hackers.

In short, the economic incentives for HIPAA security compliance—and breach notification—simply did not exist for the healthcare industry before 2009.

In the meantime, some healthcare security teams made progress on HIPAA initiatives, forming incident response programs, setting up central logging servers, and establishing individual computer accounts for each user. Others, however, largely ignored the new rules or made cursory efforts to gradually move forward on compliance.

“If I was the CIO at one of our nation’s hospitals, I might actually decrease my HIPAA compliance budget this year,” said Grimes in 2006. “If it’s a law without any teeth, why waste the funds when there are so many other competing objectives?”29

29. Grimes, “HIPAA Has No Teeth.”

9.3.3 The Breach Notification Rule

That changed in 2009, with passage of the HITECH Act. Among other things, HITECH introduced the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule.30 An interim rule was released in 2009 and finalized with the release of the Omnibus HIPAA Rulemaking in early 2013. The final rule includes the definition of a “breach,” explicit notification requirements, and (in some cases) public disclosure requirements.

30. 45 C.F.R. §§164.400–414.

9.3.3.1 Definition of a Breach

The Breach Notification Rule defines “breach” as follows:31

31. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Part 164 Security and Privacy: 164.402 Definitions,” 78 Fed. Reg. 5566, 5695 (Jan. 25, 2013), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-01-25/pdf/FR-2013-01-25.pdf.

Breach means the acquisition, access, use, or disclosure of protected health information . . . which compromises the security or privacy of the protected health information.

The term “breach” under HITECH explicitly excludes scenarios in which PHI was unintentially accessed by a workforce member of the covered entity and similar situations.

9.3.3.2 Notification Requirements

The HIPAA Breach Notification Rule is the first federally created notification requirement for health data breaches. It requires:

Notification to Individuals - Organizations must notify each affected individual within 60 days of discovering a data breach.

Notification to the Media - For breaches “involving more than 500 residents of a state or jurisdiction,” organizations must notify “prominent media outlets.” HHS cautioned that simply updating the organization’s website did not sufficiently meet the requirements of notification.

Notification to the Secretary - Organizations must notify the HHS secretary after discovering a breach. For breaches involving more than 500 individuals, organizations must notify the secretary within 60 days of discovering the breach. For smaller breaches, each organization must keep a log and provide notification to the secretary within 60 days following the end of the calendar year.

The Breach Notification Rule applies to all breaches discovered on or after September 23, 2009, but the HHS does not “impose sanctions for failing to provide the required notification for breaches discovered before February 22, 2010.”32

32. GBS Directions, “HIPAA Privacy Breach Notification Regulations,” Technical Bulletin 8 (2009), 8, https://www.ajg.com/media/850719/technical-bulletin-hipaa-privacy-breach-notification-regulations.pdf.

9.3.3.3 The Wall of Shame

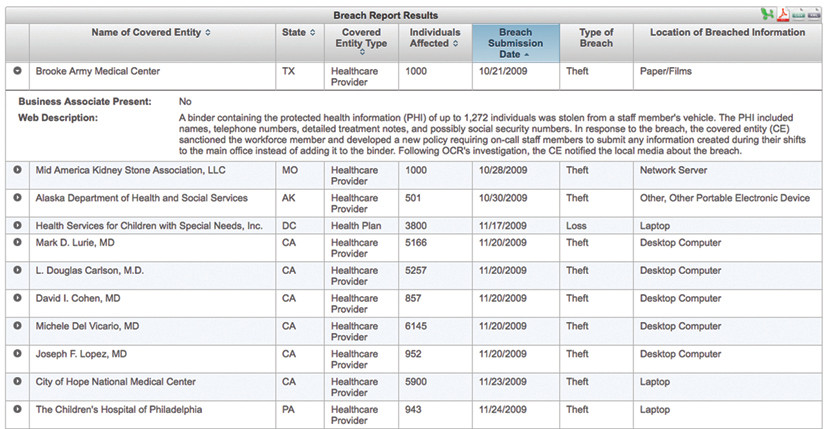

The HITECH Act requires the HHS secretary to “post a list of breaches of unsecured protected health information affecting 500 or more individuals.”33 The list is currently posted as a searchable web application, which lists (among other things) the name of each covered entity, breach submission date, number of individuals affected, and a brief summary of the breach. Now, in addition to financial penalties and potential media attention, organizations that experience a breach are immortalized on what security professionals colloquially referred to as the “Wall of Shame,” as shown in Figure 9-1.

33. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Cases Currently Under Investigation,” Office for Civil Rights, accessed October 14, 2016, https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf.

9.3.3.4 Presumption of a Breach

Critically, the final Breach Notification Rule flips the breach definition process on its head. It states:

[A]n impermissible use or disclosure of protected health information is presumed to be a breach unless the covered entity or business associate, as applicable, demonstrates that there is a low probability that the protected health information has been compromised.

This change (released in January 2013) had far-reaching consequences. Absence of evidence no longer meant that organizations could sweep potential breaches under the rug. Covered entities and business associates now have strong incentives to implement file system access logging, network monitoring, and similar tools that allow them to rule out a breach. Combined with the dramatic increases in penalties, healthcare organizations now have a solid business case for investing in security infrastructure.

9.3.3.5 The Four Factors

According to HHS, an affected entity must conduct a risk assessment to determine whether a suspected breach has compromised PHI. This risk assessment should include at least the following four factors:34

34. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Breach Notification Rule,” accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/breach-notification/index.html.

The nature and extent of the protected health information involved, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of reidentification;

The unauthorized person who used the protected health information or to whom the disclosure was made;

Whether the protected health information was actually acquired or viewed; and

The extent to which the risk to the protected health information has been mitigated.

If an entity concludes that there was a “low probability” of compromise based on this risk assessment, then it is permissible to conclude that a breach did not occur. Regardless, the entity is required to maintain documentation of the risk assessment.

HHS points out that notifications are required only if the breach involves unsecured PHI, or PHI that “has not been rendered unusable, unreadable, or indecipherable to unauthorized persons through the use of a technology or methodology specified by the Secretary in guidance.”

In the United States, HITECH-regulated data is currently one of the few instances where data is presumed to be breached unless an organization can demonstrate otherwise. Under most U.S. state and federal regulations, there is little guidance regarding how to practically determine that a breach has occurred, particularly when the evidence does not exist or is inconclusive. As a result, organizations that maintain health data now have greater incentive to monitor and collect evidence than their peers in most other industries. In the next section, we’ll discuss how this can skew data breach statistics.

9.3.4 Penalties

The HITECH Act also requires HHS to issue a dramatic increase in financial penalties for violations and to impose penalties for willful neglect. “Prior to the enactment of the HITECH Act, the imposition of [civil money penalties] under HIPAA was limited to a maximum of $100 per violation and $25,000 for all violations of an identical requirement or prohibition occurring within the same calendar year,” advised the law firm McGuire Woods in a legal alert. “[T]he amount of the penalty increases with the level of culpability, with maximum penalties for violations of the same HIPAA provision of $1.5 million per year.”35 (Note that the penalties were further increased over time.)

35. McGuire Woods, “HIPAA Omnibus Final Rule Implements Tiered Penalty Structure for HIPAA Violations,” McGuire Woods Legal Alert, February 14, 2013, https://www.mcguirewoods.com/Client-Resources/Alerts/2013/2/HIPAA-Omnibus-Final-Rule-Implements-Tiered-Penalty-Structure-HIPAA-Violations.aspx.

The HITECH Act establishes four categories of culpability:

Unknowing

Reasonable cause

Willful neglect - corrected within 30 days of discovery

Willful neglect - not corrected within 30 days of discovery

There are also four corresponding tiers of penalties, which increase based on the level of culpability. “Our observation has been that HHS tends to give bigger fines when people are not trying. You’d better be trying, or you’re going to get in big trouble,” said Michael Ford, information security officer for the Boston Children’s Hospital.36

36. Michael Ford, interview by the author, June 20, 2017.

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), charged with actually conducting investigations and levying fines, met with shocking pushback in one of its first investigations. Cignet Health of Temple Hills, Maryland, was reported to the OCR after refusing to release the medical records of 41 patients, in accordance with HIPAA requirements. Moreover, when the OCR contacted Cignet to investigate, “They failed to appear, they ignored us, they refused to engage with us to have us understand why they were doing this,” said OCR Director Georgina Verdugo. The agency bestowed Cignet Health with the dubious honor of the first HIPAA fine to be imposed on a covered entity, announced on February 22, 2011: $4.3 million total, which included $1.3 million for failing to release the patient medical records, and a whopping $3 million because “Cignet failed to cooperate with OCR’s investigations on a continuing daily basis from March 17, 2009, to April 7, 2010, and that . . . failure to cooperate was due to Cignet’s willful neglect to comply with the privacy rule.”37

37. “HHS Imposes a $4.3 Million Civil Money Penalty for Violations of the HIPAA Privacy Rule,” Business-Wire, February 22, 2011, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20110222006911/en/HHS-Imposes-4.3-Million-Civil-Money-Penalty.

Just two days later, the OCR announced a settlement agreement with Massachussetts General Hospital, which required the hospital to pay $1 million after an employee left documents containing PHI on the subway.38 The OCR said in its press release:

38. Shannon Hartsfield Salimone, “HIPAA Enforcement Escalates: What Does This Mean for the Health-care Industry?” ABA Health eSource 7, no. 8 (April 2011), https://www.americanbar.org/content/newsletter/publications/aba_health_esource_home/aba_health_law_esource_1104_salimone.html.

We hope the health care industry will take a close look at this agreement and recognize that OCR is serious about HIPAA enforcement. It is a covered entity’s responsibility to protect its patients’ health information.39

39. Chester Wisniewski, “HIPAA Fines Prove the Value of Data Protection,” Naked Security by Sophos, February 25, 2011, https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2011/02/25/hipaa-fines-prove-the-value-of-data-protection.

By 2016, the media was reporting that the OCR had “stepped up its enforcement activities in recent years” and had become “more aggressive in enforcing HIPAA regulations.” In 2016 alone, the agency received payments in excess of $22 million, including a record $5.5 million penalty on Advocate Health System for three data breaches that affected millions of patients.

“When you start seeing multiple-million-dollar fines . . . you get the feeling there’s teeth there,” said Ford.40

40. Ford interview.

9.3.5 Impact on Business Associates

The HITECH Act dramatically changed the requirements for “business associates” of covered entities. Suddenly, attorneys, IT firms, and vendors around the country were themselves required to comply with HIPAA security and privacy rules, report breaches of PHI to the covered entities that they served, and make sure that any subcontractors they leveraged were contractually obligated to do the same.

It was an important leap forward for patient privacy—but the estimated 250,000 to 500,000 business associates of covered entities were not ready. According to a survey conducted by the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) in December 2009: “[B]usiness associates, those who handle private patient information for healthcare organizations—including everyone from billing, credit bureaus, benefits management, legal services, claims processing, insurance brokers, data processing firms, pharmacy chains, accounting firms, temporary office personnel, and offshore transcription vendors—are largely unprepared to meet the new data breach-related obligations included in the HITECH Act.”41

41. HIMSS Analytics and ID Experts, Evaluating HITECH’s Impact on Healthcare Privacy and Security (Burlington, VT: HIMSS Analytics, November 2009), https://web.archive.org/web/20111112031528/ http://www.himssanalytics.org/docs/ID_Experts_111509.pdf.

In fact, many business associates had no idea that they were suddenly required to adhere to this new regulation. The HIMSS study revealed that “[o]ver 30 percent of business associates surveyed did not know the HIPAA privacy and security requirements have been extended to cover their organizations.”42

42. HIMSS Analytics and ID Experts, Evaluating HITECH’s Impact.

At the time, HIMSS found that more than half of the healthcare entities surveyed said that they would “renegotiate their business associate agreements” as a result of the HITECH Act, and nearly half “indicated that they would terminate business contracts for violations.” However, in the years immediately following passage of the HITECH Act, business associates were rarely subjected to audits, and oversight was limited.

9.4 Escape from HIPAA

Since HIPAA, and many similar laws, apply only to certain entities such as healthcare providers, the question of who generated the data is core to determining what laws apply and whether a data exposure event constitutes a “breach” under the law.

There are primarily three ways that regulated data “escapes” the confines of HIPAA/ HITECH:

Data Breach: Breached information can be traded and sold, or used to make derivative data products.

Mandated Information Sharing: State regulations may require healthcare entities to provide information to third parties for purposes of public interest, such as tracking and managing epidemics. State Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) are one such example.

Deidentification/Reidentification: Under HIPAA, data can be “deidentified” and released without restriction. However, reidentification is always a risk, and the emergence of big data analytics and data brokers has made reidentification much easier.

In addition, certain personal health information bypasses HIPAA from the very beginning because it is created outside the typical caregiver/patient relationship. Data subjects are often surprised to learn that “noncovered entities” that hold their data are not, in fact, bound by federal HIPAA/HITECH regulations.

9.4.1 Trading Breached Data

In the United States, health information is protected by HIPAA only when it is in the hands of a “covered entity” or “business associate.” News outlets such as ESPN, for example, aren’t included, as the vignette at the beginning of the chapter showed.

While the legality of leveraging stolen data is questionable at best, the lack of global legal standardization means that there are many jurisdictions where U.S. data protection laws simply would not apply. Furthermore, an increasingly complex web of data brokers facilitates data laundering, which can enable stolen data to reenter legitimate markets. See Chapter 2, “Hazardous Material,” for details.

9.4.2 Mandated Information Sharing

PDMPs are a prime example of how legally mandated information sharing increases the risk of data breaches. These databases are treasure troves of health information that are designed to be widely accessible for the purposes of reducing drug abuse. Forty-nine states and the District of Columbia and the territory of Guam have a PDMP. While the details vary from state to state, typically doctors and pharmacists are required to report prescriptions of schedule II-IV or II-V drugs to the state. The state maintains a database that includes extensive details of each person, along with detailed prescription records.

Doctors and pharmacists are required to check the PDMP database prior to prescribing or dispensing medication. This means that the state PDMP databases are typically available online to tens of thousands of doctors, pharmacists and their staff, and often law enforcement agencies, state Medicaid administrators, and others. The database may also be accessible to practitioners in neighboring states, such as Maryland’s PDMP, which is available to prescribers in Delaware, Washington, DC, West Virginia, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. In the New York State, the Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement advertises that it “provides millions of secure Official New York State Prescriptions annually to over 95,000 prescribing practitioners across the State.”43

43. New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement, accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic (accessed January 18, 2018).

The fact that PDMPs are so widely accessible leaves them at high risk of unauthorized access. Consider that any medical practitioner around the state who has a PDMP password stolen or a computer infected with malware can be a gateway to this extensive database. By their nature, the PDMP databases are directly accessible via the web and typically protected only by single-factor authentication (username and password) chosen by the practitioner.

Virginia residents discovered in 2009 that their records had been accessed when the state Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) website was defaced, and the hacker left the following message:44

44. Cary Byrd, “Stolen Files Raise Issues About Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs,” eDrugSearch, May 11, 2009, https://edrugsearch.com/stolen-records-raise-questions-about-prescription-drug-monitoring-programs.

In *my* possession, right now, are 8,257,378 patient records and a total of 35,548,087 prescriptions. Also, I made an encrypted backup and deleted the original. Unfortunately for Virginia, their backups seem to have gone missing, too. . . . For $10 million, I will gladly send along the password. You have 7 days to decide. If by the end of 7 days, you decide not to pony up, I’ll go ahead and put this baby out on the market and accept the highest bid. Now I don’t know what all this s—is worth or who would pay for it, but I’m bettin’ someone will. Hell, if I can’t move the prescription data at the very least I can find a buyer for the personal data (name, age, address, social security #, driver’s license #).

Virginia’s governor, Tim Kaine, elected not to pay the ransom. Two months later, the state formally sent breach notification letters to more than 530,000 people whose SSNs may have been stored on the system.45

45. Bill Sizemore, “Virginia Patients Warned about Hacking of State Drug Web Site,” Virginia Post, June 4, 2009, http://hamptonroads.com/2009/06/oficials-hacker-may-have-stolen-social-security-numbers.

At the time, Virginia had a breach notification law that applied to SSNs, credit card numbers, and similar data, but it did not include health or medical data (a breach notification law for medical information was subsequently passed in 2010, although it applies only to state government agencies or organizations “supported . . . by public funds”).46 As a result, the state did not notify all patients with data in the hacked system. Instead, only persons who had their SSNs in the database were notified. An FAQ on the state’s website explained, “If you do have a prescription record in the PMP and it did not contain a nine-digit number that could be a Social Security number, you will not be sent a letter.”47

46. Va. Code Ann. § 32.1-127.1:05, Breach of Medical Information Notification (2010), https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title32.1/chapter5/section32.1-127.1:05.

47. Virginia Department of Health Professionals, “Questions and Answers: Updated June 5, 2009,” accessed January 18, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20090618021638/ http://www.dhp.virginia.gov/misc_docs/PMPQA060509.pdf.

9.4.3 Deidentification

The HIPAA Privacy Rule allows covered entities and business associates to “deidentify” PHI and subsequently share the resulting data with anyone, sans HIPAA regulations. “Deidentification” in this context refers to the process of modifying data sets of medical information so that there is a low risk that individual subjects can be identified.

Under HIPAA, PHI can be deidentified in one of two ways, as illustrated in Figure 9-2 and described in the following list:

Expert Determination: An expert uses “statistical and scientific principles” to determine that the risk of individual identification is very low.

Safe Harbor: Eighteen types of identifying information are removed from the record. Examples include names, email addresses, facial photographs, SSNs, and more.

Theoretically, deidentifying data enables organizations to retain much of the value of medical datasets, while reducing the risk of privacy injury for individual subjects. According to the HHS, “the Privacy Rule does not restrict the use or disclosure of de-identified health information, as it is no longer considered protected health information.”48

48. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Guidance Regarding Methods for De-identification of Protected Health Information in Accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/special-topics/de-identification/index.html.

The OCR specifically refers to deidentification as one of the factors to be considered in evaluating whether a cybersecurity incident is a breach (and therefore subject to the breach notification laws). When assessing the risk of a breach, organizations are required to consider the “types of identifiers” and “likelihood of re-identification.”49 Since a breach under the HITECH Act is defined as “an impermissible use or disclosure of protected health information” held by a covered entity or business associate, unauthorized access to de-identified information is not typically considered a breach.

49. U.S. HHS, “Breach Notification Rule”.

Deidentification is one of the ways that health data can “escape” the HIPAA-regulated environment. Deidentified data can be freely sold, transferred, or exposed to the world without regulation under HIPAA. However, the HHS website clearly explains that “de-identified data . . . retains some risk of identification. Although the risk is very small, it is not zero, and there is a possibility that de-identified data could be linked back to the identity of the patient to which it corresponds.”50 If sensitive data were deidentified, transferred to a third party, and subsequently reidentified, then the original sensitive data could potentially exist outside of a HIPAA-regulated organization.

50. U.S. HHS, Guidance.

9.4.4 Reidentification

“Reidentification,” is the process of adding identifying data back to previously deidentified data sets. Reidentification may be done for a variety of reasons: for example, to match up records across two or more data sets; for ethical notification of subjects in the event that a research study turns up important findings; or for less ethical concerns such as marketing and personal data mining. To support reidentification, HIPAA explicitly permits entities to replace identifying information with a code. The OCR is clear that “[i]f a covered entity or business associate successfully undertook an effort to identify the subject of de-identified information it maintained, the health information now related to a specific individual would again be protected by the Privacy Rule, as it would meet the definition of PHI.”51

51. U.S. HHS, Guidance.

While explicit identifiers can be removed, the very factors that make data sets valuable for researchers (and commercial entities) can also be used to define unique profiles, and ultimately reidentify users. Researchers have demonstrated that reidentification can be much easier than people realize. Specific health conditions, treatment dates and times, names of physicians, location of treatment, and prescription histories function like a digital health fingerprint.

“Health information . . . from sleep patterns to diagnoses to genetic markers . . . can paint a very detailed and personal picture that is essentially impossible to de-identify, making it valuable for a variety of entities such as data brokers, marketers, law enforcement agencies, and criminals,” said Michelle De Mooy, the director of the Privacy & Data Project at the Center for Democracy & Technology.52

52. Adam Tanner, “The Hidden Trade in Our Medical Data: Why We Should Worry,” Scientific American, January 11, 2017, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-hidden-trade-in-our-medical-data-why-we-should-worry.

9.4.5 Double Standards

Reidentification is not a crime. While a few states require purchasers to sign or acknowledge a “data use agreement” in order to receive “deidentified” information, HIPAA does not require it for transfer of deidentified data. The result is that a covered entity (or business associate) can deidentify data in compliance with the law and transfer it to a third party without restriction. The third party could then attempt to reidentify the data. If successful, the third party would then be in possession of the same data as the covered entity, sans HIPAA/HITECH regulation.

Imagine that you suddenly discover, to your horror, that your organization accidentally posted people’s names and known medical problems on the web. Is that a data breach? It depends. If you work for a healthcare provider, then HIPAA/HITECH applies to you, and you would need to consider the definition of a breach in HIPAA/HITECH. On the other hand, if you work for a marketing firm that has re-identified data, it might be that no relevant law applies to you.

That means that two different organizations could expose the exact same data, and in one case it would be a “breach,” and in the other case it wouldn’t—simply by virtue of how the databases came to exist.

9.4.6 Beyond Healthcare

Fitness trackers, mobile health apps, paternity tests, social media sites, and many other emerging technologies typically fall outside the bounds of the caregiver/patient relationship, and therefore are not covered by regulations such as HIPAA. These “noncovered entities” (NCEs) often collect extensive health and medical-related details about individuals, which they can share or sell it with few restrictions.

The proliferation and spread of health information through NCEs increases the risk of personal health data exposure. NCEs are typically not bound by specific regulations that require them to safeguard health data. The HHS reported in 2016 that “NCEs have been found to engage in a variety of practices such as online advertising and marketing, 139 commercial uses or sale of individual information, and behavioral tracking practices, all of which indicate information use that is likely broader than what individuals would anticipate.”53

53. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Examining Oversight of the Privacy & Security of Health Data Collected by Entities Not Regulated by HIPAA (Washington, DC: HHS, June 2016), https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/non-covered_entities_report_june_17_2016.pdf.

Absent regulations and oversight requiring specific cybersecurity safeguards, NCEs can be particularly high-risk environments. Since there are no standard requirements for incident detection methods and oversight, a high percentage of potential breaches may simply go undetected in these environments. A 2012 study of personal health record (PHR) vendors by Maximus Federal Services found that “[o]nly five of the [41] PHR vendors surveyed referenced audits, access logs, or other methods to detect unauthorized access to identifiable information in PHRs.”54

54. Maximus Federal Services, Non-HIPAA Covered Entities: Privacy and Security Policies and Practices of PHR Vendors and Related Entities Report, December 13, 2012, https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/maximus_report_012816.pdf.

Subjects often do not realize that NCEs have great freedom to share or sell their health information. For example, in May 2017 attorney Joel Winston pointed out that by submitting DNA samples to the popular service AncestryDNA for analysis, users “grant[ed] AncestryDNA and the Ancestry Group Companies a perpetual, royalty-free, world-wide, transferable license to use your DNA . . . and to use, host, sublicense and distribute the resulting analysis to the extent and in the form or context we deem appropriate on or through any media or medium and with any technology or devices now known or hereafter developed or discovered.”55

55. Ancestry.com, “AncestryDNA Terms and Conditions (United States),” accessed January 18, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20170521230901/ https://www.ancestry.com/dna/en/legal/us/termsAndConditions.

“[H]ow many people really read those contracts before clicking to agree? And how many relatives of Ancestry.com customers are also reading?” asked Winston. AncestryDNA changed its terms of service shortly thereafter.

Health information persists as an asset—and a risk—even after a company merges, liquidates, or is acquired. AncestryDNA itself takes pains to point this out in its current privacy statement:56

56. Ancestry.com, “Ancestry Privacy Statement,” accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.ancestry.com/dna/en/legal/us/privacyStatement#3.

[A]s our business continues to grow and change, we might restructure, buy, or sell subsidiaries or business units. In these transactions, customer information is often one of the transferred assets, remaining subject to promises made in then prevailing privacy statements. Also, in the event that AncestryDNA, or substantially all of its assets or stock are acquired, transferred, disposed of (in whole or part and including in connection with any bankruptcy or similar proceedings), personal information will as a matter of course be one of the transferred assets.

NCEs are not bound by the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule, and therefore are not required to report a “breach” of health-related data under HIPAA/HITECH. However, the Federal Trade Commission’s Health Breach Notification Rule, which went into effect in 2010, does apply to vendors of personal health records, their service providers, or “related entities.” This rule requires organizations to notify affected U.S. citizens or residents, the FTC, and in certain cases, the media, when there has been “unauthorized acquisition of PHR-identifiable health information that is unsecured and in a personal health record.”57 The FTC may also investigate when a suspected breach indicates that an organization may have engaged in “unfair or deceptive acts or practices” since that is part of the FTC’s core mandate.58

57. Federal Trade Commission, “Health Breach Notification Rule: 16 CFR Part 318,” accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/rules/rulemaking-regulatory-reform-proceedings/health-breach-notification-rule.

58. Thomas Rosch, Deceptive and Unfair Acts and Practices Principles: Evolution and Convergence (Washington, DC: FTC, May 18, 2007), 1, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_statements/deceptive-and-unfair-acts-and-practices-principles-evolution-and-convergence/070518evolutionandconvergence_0.pdf.

9.5 Health Breach Epidemic

Suddenly, in 2010 healthcare data breaches began popping out of the woodwork. Many professionals concluded that meant healthcare breaches were on the rise. Statistics reported by the Identity Theft Resource Center seemed to indicate that the number of healthcare data breaches more than doubled between 2009 and 2010.59

59. Identity Theft Resource Center, ITRC Breach Statistics 2005–2016, accessed January 18, 2018, https://www.idtheftcenter.org/images/breach/Overview2005to2016Finalv2.pdf.

The American Bar Association published an insightful analysis by attorney Lucy Thomson, who began: “Massive data breaches are occurring with alarming frequency. An analysis of data breaches by industry should provide a wake-up call for the health care industry. . . . Health care breaches have increased steadily from fourth place in 2007 through 2009 to second place behind only the business sector in 2010 and 2011.”60

60. Lucy L. Thomson, Health Care Data Breaches and Information Security: Addressing Threats and Risks to Patient Data (Chicago: American Bar Association, 2013), 253–67, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/books/healthcaredatabreaches.authcheckdam.pdf.

And yet, was it really the case that the number of breaches in healthcare increased so dramatically? Or were there other factors at play?

9.5.1 More Breaches? Or More Reporting?

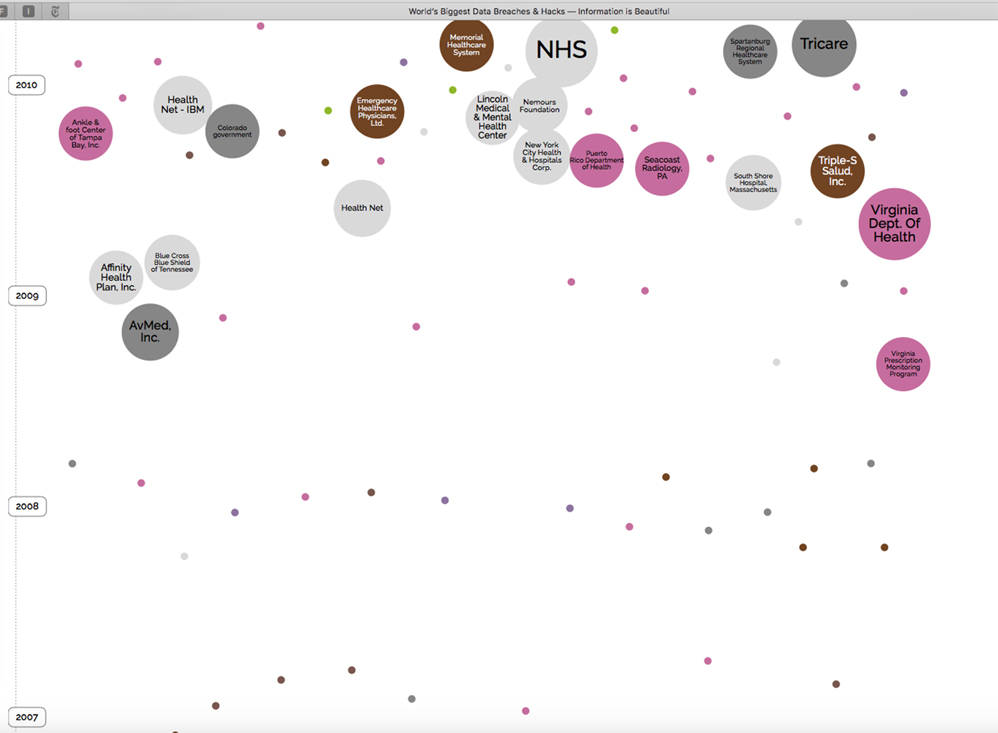

The website InformationIsBeautiful.net has an interactive page called “World’s Biggest Data Breaches & Hacks: Selected Losses Greater Than 30,000 Records.” As shown in Figure 9-3, the chart illustrates data breaches by year, filtered in this case to show only healthcare industry breaches. The size of each bubble indicates the approximate number of exposed records.

What’s striking is the absence of major breaches reported before 2009: The earliest major breach was the Virginia PMP, discussed earlier in the chapter. After that, AvMed, Inc. reported a theft of two laptops that occurred in December 2009 and affected 1.2 million patients, and subsequently Affinity Health Plan, Inc. reported in April 2010 that the data of more than 400,000 patients may have been exposed on an office copier hard drive that was not properly wiped before reuse.

Of course, prior to September 23, 2009, there was no legal definition of a “breach” of protected health information, at least under federal law. There was no Breach Notification Rule that explicitly required organizations to notify affected persons. There was no requirement to notify the media or HHS. There was no “Wall of Shame” where the public could view reported breaches. There was no threat of a fine if an organization did not notify affected parties quickly enough.

September 2009 (the effective date of the Breach Notification Rule) and February 2010 (the date after which organizations could be sanctioned for failing to provide proper notice) introduced massive regulatory changes. These changes almost certainly triggered a substantial rise in the number of health data breaches that were reported. Furthermore, the presumption of a breach incentivized many organizations to invest in network monitoring and logging in a way they never had before, giving these organization new capability to detect data breaches themselves.

In other words, the number of healthcare data breaches that occurred did not necessarily rise. Instead, for the first time, the health industry had defined what a breach was and gave organizations incentives to detect and report data breaches. Suddenly, the public had a glimpse of the rest of the iceberg.

9.5.2 Complexity: The Enemy of Security

Why so many healthcare breaches? As the issue erupted into the public spotlight, industry cybersecurity professionals wrestled with a myriad of challenges. “There are two things that make health care such an attractive target,” explained Larry Pierce, manager of information security and enterprise management at Atlantic Health System. “One is the value of the data, and two is that safeguards and protections are sometimes not in place to protect these environments.”61

61. Larry Pierce, interview by author, June 20, 2017.

“The worst enemy of security is complexity,” wrote Bruce Schneier, the renowned security expert, in 1999.62 If that’s the case, then healthcare organizations have a powerful enemy, indeed.

62. Bruce Schneier, “A Plea for Simplicity: You Can’t Secure What You Don’t Understand,” Schneier on Security, November 19, 1999, https://www.schneier.com/essays/archives/1999/11/a_plea_for_simplicit.html.

In the next few sections, we will explore specific factors that contribute to the epidemic of healthcare data breaches: the complexity of their IT environments, third-party dependencies, the lack of a perimeter, a mobile workforce, the emergence of personal mobile devices and social media, increasing reliance on the cloud, and more. Technological advances in each of these areas have increased the risk of data breaches and also changed how we respond.

From a veritable jungle of specialized software applications to unique staffing issues and the emergence of Internet of Things (IoT), healthcare technology has become wildly complex. As we will see, it’s hard for security professionals to keep up.

9.5.2.1 Specialized Applications

Modern healthcare facilities are fantastically complex environments, from an information management perspective. Hospital networks typically have admission-discharge-transfer (ADT) software systems to track patients from the time they step into the facility to the time they are discharged. The ADT interfaces with the central EMR, used throughout the organization.

Individual departments maintain specialized applications, such as radiology, laboratory, or pharmacy systems. All of these applications need to be integrated with the ADT and the EMR in order to maintain up-to-date, accurate information on patients. Data is transferred between software applications via interface engines using the international Health Level-7 (HL7) protocol.

“Remote organizations receive and send data back to the EMR,” described Michael Ford, Information Security Officer at the Boston Children’s Hospital. “Prescriptions go out to a pharmacy somewhere using HL7.” Data is also shared with researchers and data warehouses, often in real time.

“There is patient data flowing back and forth between hundreds of systems,” said Ford. “It looks like a giant brain. It’s very difficult to map it all.”63

63. Ford interview.

Pierce pointed out that “environments within health care [are] significantly more complex than what you’d find in the banking industry or even the government. Most health care systems have in excess of 300 applications and programs that they have to support—all with remote access.”64

64. Pierce interview.

9.5.2.2 Staff and Services

When you compare healthcare environments to those of banking or other industries, it’s easy to see why security is a challenge. Like banks, hospitals store highly sensitive financial and identification data, in addition to medical details. Unlike banks, hospitals are open to the public 24/7. This simple fact makes it challenging to find windows of time for installing software patches or running disaster recovery tests.

Banks employ a clearly defined set of personnel: tellers, loan officers, managers, to name a few. Hospitals, however, include full-time and part-time staff, doctors who may rotate through multiple facilities, researchers employed by academic institutions, and more. Care providers who rotate shifts all need access to patient data, and it is not possible to predict in advance precisely who will need access to a specific patient’s medical record. This has a major impact on access control models in hospitals. Rather than place granular restrictions on which staff can access a particular patient’s record, healthcare facilities tend to invest more in post treatment analytics to detect inappropriate access and deter future issues.

9.5.2.3 Patients

At a hospital, when a patient is wheeled in from an ambulance, he or she may not possess an ID card or even the ability to speak—but hospital staff still need to accurately identify the patient, pull up the right medical record, and provide treatment. Contrast this with a bank, where it’s normal to require that customers provide identification or answer authentication questions in order to receive service. According to Pierce, Atlantic Health System addressed the issue of patient identification by installing palm scanners in the emergency room department—yet another high-tech (and pricey) system that must be integrated into the hospital’s IT environment.

9.5.2.4 Internet of Things

The complexity of healthcare technology only increases as technology advances. Today, smart refrigerators track breast milk expiration dates using barcode readers and transmit temperature monitoring data across the Internet to cloud apps, which can be accessed via a mobile phone app. Patients wander through the halls, implanted with lifesaving devices such as cardioverter defibrillators, which can be remotely controlled via radiofrequency signals. The emergence of IoT and the ubiquitous permeation of cellular networks means that healthcare facilities are literally crawling with networked devices that are attached to patients in their care—yet many of these devices are outside the control of local IT staff.

9.5.2.5 Hospital Infections

Attackers develop malware designed to quietly siphon information out of healthcare networks without impacting operations, in order to retain longer-term footholds. “Botnets” of infected devices can be sold to criminal groups and used to quietly steal valuable information from affected systems. “Stealthy” malware of this kind typically does not impact hospital operations and can remain undetected indefinitely.

Researchers at security firm TrapX discovered a classic example after they installed their security product at a healthcare organization. The researchers noticed alerts from their software indicating that a picture archive and communications systems (PACS) used by the radiology department had been hacked. The initial source of the compromise was a user workstation elsewhere in the hospital; the user had surfed to a malicous website and triggered a classic “drive-by download” attack. Once the PACS was infected, the attackers moved laterally through the facility’s network, infecting a nurse’s workstation.

“Confidential hospital data was being exfiltrated to a location within Guiyang, China,” detailed TrapX. “It is uncertain how many data records in total were successfully exfiltrated. Communications went out encrypted using port 443 (SSL) and were not detected by existing cyber defense software.”65

65. Trapx Labs, Anatomy of an Attack: Industrial Control Systems Under Siege (San Mateo, CA: Trapx Security, 2016), 16–18, http://www.trapx.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/TrapX-AOA-Manufacturing.pdf.

According to the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, 24% of healthcare breaches in their study were discovered months or years after the fact. While more than half were discovered in days or less, the researchers noted that “[u]nfortunately . . . we found out that the majority of them were breaches involving misdeliveries of information or stolen assets.” Cases of improper access to electronic health records were simply not detected as quickly, due to lack of effective internal monitoring systems.66

66. “Verizon’s 2017 Data Breach Investigations Report,” Verizon Enterprise, 2017, http://www.verizonenterprise.com/resources/reports/rp_DBIR_2017_Report_en_xg.pdf.

“Most organizations tend to focus on perimeter defenses only, but the most effective security strategies need to include . . . the whole network, machine analytics, behavioral analytics.” says Pierce. He cites tight budgets throughout the health care industry as a major obstacle. “Health care operates on very, very slim margins. . . . There are monitoring tools, but most organizations with the money they have tend to focus on perimeter defenses only.”67

67. Pierce interview.

In the complex 24/7 hospital environment, it can be challenging to successfully deploy automated IDS without generating a constant barrage of false positive alerts. The traditional reliance on perimeter defenses is no longer effective.

9.5.3 Third-Party Dependencies

Healthcare organizations rely heavily on third parties to supply, manage, and maintain specialized software and equipment. As a result, they inherit security risks introduced by outside manufacturers and vendors. In this section, we will review the risks introduced by clinical equipment and vendor remote access, and highlight critical inconsistencies between the way the HHS and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulate data breaches. Along the way, we will provide tips for reducing security risks introduced by third parties and discuss the impact of these organizations on data breach response.

9.5.3.1 Frozen in Time

Clinical equipment and software can pose a huge cybersecurity risk for healthcare providers. Often, manufacturers prioritize functionality over security, and once a product is released, security updates may be few and far between. Even when security is a priority in the development phase, once a system is deployed, all bets are off.

It’s not always clear who is responsible for managing system security (the manufacturer or the purchaser’s IT staff). If the purchaser is responsible for handling security, this can be an overwhelming task. Healthcare providers rarely have the staff or intimate knowledge of the equipment to properly secure all of their clinical devices on an ongoing basis (especially given the large number of clinical devices at any one healthcare facility).