How do you identify instances of the Facts learning domain?

What strategies are appropriate for presenting content in the Facts learning domain?

What sequences are appropriate for practicing content in the Facts learning domain?

In this chapter, you will learn about teaching Facts, often considered the most difficult learning domain to teach. Facts are essentially arbitrary associations. For example, "Columbus discovered America in 1492" is a Fact because the date, "1492," is associated with the statement, "Columbus discovered America." Facts are challenging to teach because the learner must memorize the association. With the other learning domains (Concepts, Principles, and Procedures), we can assist the learners by providing them with a meaningful structure in which we can embed information. Learning is easier when meaningful connections can be made to prior knowledge. However, Facts are the least amenable domain for creating structures because often the associations are arbitrary. Effective strategies for creating a structure for Facts include elaborative verbal explanations and carefully designed repetition sequences.

What is a Fact? First, instructional designers use the term "Fact" differently than does the general public. Most people think of Facts as true or verifiable propositions; a useful designation because they allow one to create a logical distinction between assertions that are true and assertions that are false. In this sense, if a statement is false then it is not a Fact.

However, when we are discussing Facts from an instructional designer's point-of-view, as a learning domain, we are interested in being able to recognize and recall the associations, assertions, and propositions themselves and not with determining whether they are true. It is the association that is important, and not the veracity of the proposition.

Merrill (1983) describes Facts as "arbitrarily associated pieces of information such as a proper name, a date or an event, the name of a place or the symbols used to name particular objects or events" (p. 287). Questions such as, "On an interstate highway ramp, what is the sign for Yield?" and "What is the value of the U.S. national debt" are Fact-based questions; each of these propositions proposes an association that the learner must recognize or recall.

Facts, sometimes labeled as declarative knowledge or verbal information, may include what is called organized discourse, which consists of a sequence of Facts leading to an extended meaning. Learners understand organized discourse by following a chain of reasoning. For example, the statement, "The author that recommends the recipe be made either outdoors or in commercial kitchen, since the process creates an incredible amount of smoke that will set off your own and your neighbors' smoke alarms" (Wu, 2007), is a declarative statement that requires the learner to recall a set of integrated associations.

In most cases, learners must memorize Facts. The less arbitrary the elements of a Fact are, the easier they are to memorize (Ausubel, 2000). This is because knowledge is stored in our brains as a set of neuron associations and connections (Zull, 2002). The more neuron associations a Fact connects to, the more easily it can be recalled. For example, Facts, when in the form of organized discourse, are relatively easy to recall because there is a context provided. However, Facts such as recalling one's social security number are more difficult because the number sequence is essentially arbitrary.

When teaching Facts, as with any learning domain, you will have to make a decision as to whether your will use a direct strategy (guided presentation and practice) or a discovery strategy (learners construct their experience). This text focuses on direct strategies; however, you should be familiar with discovery strategies as well because there are situations in which increasing the learners' responsibility for their learning is appropriate.

A direct instructional strategy for the Fact domain consists of presenting the learners with the Facts and clarifying which associations you expect the learners to make. A discovery instructional strategy could involve asking the learners to search for information required to make an association. For example, you could ask the learners to conduct a web search for the dates of the Act of Toleration, Leisler's Rebellion, and the Glorious Revolution. A direct strategy would simply have provided the learners with this information directly, which has the advantage of being quick and accurate. The discovery approach is a bit more cumbersome, but has the advantage of providing context for the learners, which may assist them in long-term retention.

To demonstrate mastery of an objective classified in the Fact learning domain, the learner will have to be able to associate parts of propositions with their counterparts.

Fact presentations consists of three types of strategies: (1) attention management, (2) cognitive load management, and (3) structural management that all align with sensory memory, working memory, and long-term memory. In some cases, all of these strategies could be used to teach an instructional objective; however, often a small set of strategies will be sufficient.

When instructing the learners on an association or verbal discourse, the prose should be focused and organized for easy readability. The learners should not have to work to understand the association. Writing for instructional software should keep the learners' interest.

One of the simplest things an instructional designer can do to enhance the learning of Facts is to make the required associations as clear as possible. Often this involves isolating the elements to be associated from a cluttered background. For example, to a novice the organs in the body are difficult to differentiate from one another. If a learner studies anatomy, you would want to provide him or her with an illustration that highlights a particular organ, you do this because it allows the learner to identify which organ is under discussion.

In the same way, if you are teaching learners to associate the symbols in an electrical circuit diagram with their names, you will have to make it clear which symbol you are discussing. A circuit diagram may have twenty or thirty different symbols; to assist the learners in making the appropriate association you must find a method that focus the learners' attention on a particular symbol when you mention its label.

This is a figure/ground problem (Lohr, 2007). To demonstrate an association, the figure (what you are referring to) is separated from the ground (everything else). This type of separation is critical for the most basic communication about Facts to occur. The learners must know what the association is before they can hope to retain it.

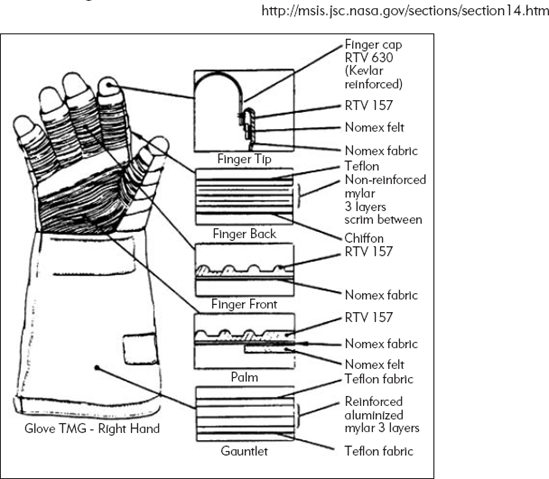

Separating a figure from its ground can be difficult to accomplish with a paper text. Paper only allows you to use arrows or colors to separate the figure from the ground in a static fashion. Often, a display in a paper document appears cluttered, as in the diagram in Figure 8.1.

A medium like Flash, however, allows you to show associations one at a time. Instead of sharing the page with every possible label, we can create an interaction that allows the learners to select an item and simultaneously view its label. That way there is no ambiguity, and the learners can focus their attention appropriately.

Many Facts come in the form of verbal discourse or narratives, which are not amenable for display in diagrams like the one in Figure 8.1. In these cases, we expect the learners to comprehend text and summarize it. We can assist the learners by organizing the text with headings, subheading, and perhaps by highlighting critical passages or terms. These techniques help the learners focus their attention productively. For example, the passage:

"A relief pitcher or reliever is a baseball or softball pitcher who enters the game after the starting pitcher is removed due to injury, ineffectiveness or fatigue. Relievers are further divided informally into closers, middle relief pitchers, left-handed specialists, set-up pitchers and long relievers,"

*(

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relief_pitcher)

may be modified, as follows, to improve its comprehensibility:

"A relief pitcher or reliever is a baseball or softball pitcher who enters the game after the starting pitcher is removed due to injury, ineffectiveness or fatigue."

Stressing the important ideas and eliminating extraneous text makes the chain of reasoning easier to follow and the content more memorable.

The Fact learning domain is unique in that the learner is likely to have to memorize many of the associations. Learners should be aware that they will have to engage in behavior that encourages memorization.

An important strategy for reducing cognitive load is to ensure that the learners are aware of the instructional objectives. If learners knows what the goals are, they can focus on tasks that will help them reach those goals instead of diffusing their thoughts in other areas. Objectives for the Fact learning domain are described by action verbs, such as associate, list, and match, among others. For example, the following demonstrate Fact instructional objectives.

The learner will be able to list the elements in Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

The learner will be able to describe the traffic law regarding four-way stops.

The learner will be able to associate the appropriate Braille symbol with the letter "r."

The learner will be able to select the appropriate definition for the label, "kidney."

To teach Facts successfully, it is important that the learner know something about the domain. Each learning domain requires different strategies for their achievement. By informing the learners of these domains, they can prepare themselves to focus on the tasks at hand. Facts are the most basic of the learning domains. Knowledge from the other learning domains is generally not prerequisites for learning Facts. While organized discourse may reference Concepts, Principles, and Procedures, they are rarely the object of analysis when learning Facts. For example, in the statement, "January 11, 1689, The Parliament of England declared King James II of England deposed," the learner is confronted with the Concepts of Parliament, king, and deposed. However, the Fact domain task is to associate the date with the event. Of course, in this case, a holistic understanding would emerge from learning both the Facts and Concepts involved in the statement.

Managing cognitive load is an important factor in teaching Facts. Extraneous and unorganized information puts more of a burden on the learners' cognitive resources than necessary. A graphic organizer is an effective method of visually organizing information for learners. Graphic organizers are particularly helpful for identifying, organizing, and demonstrating relationships among Facts (Smith & Ragan, 2005).

Graphic organizers can be diagrams or pictures used to demonstrate how ideas relate to one another. Graphic organizers help demonstrate relationships that may not be apparent to the learners and may assist them in retaining the material. A timeline of historic events or a table listing and comparing the characters of two novels are forms of graphic organizers. For example, after learning the Concept of a "straight man" (an archetypal comic foil), a learner might need to learn supporting examples of the idea. Learning to associate sets of comics with their straight men is a task of the Fact learning domain. Laying this information out in a grid makes it easy to make the appropriate associations. Table 8.1 provides an example of a graphic organizer.

The primary variable for reducing cognitive load when teaching Facts is reducing unit size in one of two ways: (1) reduce what constitutes a unit or (2) reduce the number of units. An association between a label and a definition constitutes a unit. You cannot shorten a label; however, you can select a corresponding definition version that is either basic or advanced. You can initially supply the learners with a simple definition and later expand it once the learners have mastered the initial association. For example, you could introduce the Fact "catalyst" as follows:

"A substance that speeds up a chemical reaction"

Later, you could provide an expanded definition such as:

"Chemicals that are not consumed in a reaction, but that speed up the reaction rate." (misterguch.brinkster.net/vocabulary.html).

Your second option is to reduce the number of units you teach at any one time. For example, associating a list of ten vocabulary words with their definitions is an easier task than learning a list of twenty words. It might be a more productive strategy to have your learners master the smaller set before moving on to the larger set.

Structural management is an attempt to encourage the learners to integrate the new information they encounter with their long-term memory. One of the main jobs of an instructional designer is to demonstrate a meaningful connection within and among Facts. The more connections that the learners can identify, the more likely it is that information will find itself embedded in the learners' memory structure (Zull, 2002).

For example, the chemical symbol for the element potassium is K. To the casual learner, there is not any particular reason why the letter K is associated with the element potassium. The association is essentially arbitrary. However, a bit of investigation reveals that there is some connection after all. The term "kalium" is another word for potassium. Kalium is derived from the word alkali (which itself was derived from the Arabic Al–Qaly). This additional information is helpful because it is clear that scientists chose the letter K for a reason. Once the learners understand that potassium is an alkali element (one of many), it is easier for them to develop a chain of association the letter K and potassium. In fact, the periodic table itself is a tool for organizing elements in a logical manner.

All of this "extra" information assists the learners in retaining the association between potassium and the letter K. It is important to distinguish extra information that enhances learning from extraneous information that inhibits it. For example, telling the learner that bananas are a good source of potassium may be interesting; however, it does not help to make the connection with the letter K, while the information on the word's origin, as mentioned above, could help the learners make a relevant connection.

This structural management strategy, known as elaboration, can assist the learners in making mental connections and thus enhances the meaningfulness and retrievability of the content (Fleming & Levie, 1993). Elaboration is a successful instructional strategy with regard to Facts, because it works in the way that the brain works (Zull, 2002). Elaborating the relationship between components of an association may require some detective work. It also may require some creativity. Spending time generating creative elaborations is often a wise investment.

Unfortunately, this type of elaboration often is not an option. In cases in which the elements of a Fact truly are arbitrary, the designer must attempt to try, artificially, to create meaning. Mnemonics, a method for artificially creating associations to improve the memory, are perhaps the best way to create this meaning. For example, many people confuse the spelling of desert (a dry, arid place) with dessert (a dish served as the last course of a meal). One could remember the difference by remembering the "sweet" one has two sugars (and therefore two s's). In this case, the learner makes a connection between the letter "s" and sweetness of sugar.

Another example, which has even less inherent connection, is recalling the order of colors in the visual spectrum (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet) by recalling the phrase "Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain." The first letter of each word in this phrase should remind the learner of the relevant colors. The difficulty with using mnemonics, particularly those that have no connection to their referents, is that the learner can forget them easily. The hope is that this connection is sufficient to assist the learners' retention long enough for it to become a part of their repertoire.

The final structural management technique considered for teaching Facts is repetition. Repetition is a brute force method of learning; but unfortunately, some content is not amenable to other techniques. Not surprisingly, repetition has long been associated with an increase in retention (Thorndike, 1911). Repetition is the core activity of most drill-and-practice strategies, and although drill-and-practice programs are often disparaged, the technique does have an important, if limited role.

Practice sequences attempt to remove or fade support for learners. Each type of management strategy has its own unique sequences. Table 8.2 is a sample of how these sequences might be implemented. It should be noted that rarely would all of these sequences be necessary to achieve any particular learning objective.

Table 8.2. Practice Sequences for the Fact Learning Domain.

Intermediate | Exit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Attention management: Modality | Task 1A: Concrete and Familiar: When did Columbus discover America? A. 1492 or B. 1592 | Task 1B: Concrete: In what year did a famous explorer "discover" America? A. 1492 | Task 1C: Abstract: What famous explorer is said to have "discovered" America and in what year did he do so? A. Columbus, 1492 |

Cognitive load management: Scope | Columbus discovered America in 149_. | Columbus discovered America in 1_9_. | Columbus discovered America in ____. |

Cognitive load management: Learner Action | Recognize: In which year did Columbus discover America? A. 1492 or B. 1592 | Edit: Modify the statement below so that it is accurate: Columbus discovered America in 1972. | Produce: What significant event occurred in 1492? |

Columbus was an Italian living in an age of international Colonialism, was supported by the monarchs Ferdinand and Isabelle on his voyage. In what year did Columbus make his famous voyage to America? | Columbus was an Italian living in an age of international colonialism. In what year is he said to have "discovered" America? | In what year is Columbus said to have "discovered" America? |

One final note on the Fact learning domain: a designer can classify Facts by the type of memorization that they require. Facts can be memorized verbatim (word-for-word) or by paraphrase (the meaning). For example, a learner must memorize, verbatim, an actor's line in a play or the symbol for resistance in an electronic circuit diagram. However, a learner could demonstrate comprehension or the "gist" of a newspaper story by paraphrasing it. No one would expect a learner to recall the story word-for-word.

Additionally, learners may be required to recall a Fact (verbatim of paraphrased) or they may be only required to recognize it. Recognition is an easier task because the learner has contextual signals to assist him. For example, even expert spreadsheet users find it difficult to state under which menu heading the "sort" function (or any other function) is located. However, if asked with the program in front of them, most will have no problem completing a sort task.

If a task does not require recall, it is a waste of time and effort to require the learner to master the task at that level. Similarly, some objectives simply do not require recall. For example, a learner does not need to memorize an infrequently called phone number; the learner can always look it up or store it in device like a cell phone. However, a learner uses and shares his or her own number often enough to justify verbatim recall (it would not do to paraphrase it).

When creating a practice sequence, one should pay particular attention to what type of behavior is required. If complete recall is required, having the learner recognize the proper association may be a helpful strategy to progress to the criterion behavior. However, if recall is not necessary, it may be wiser to establish practice sequences that vary in the amount of cuing provided on the way to recognizing the association without prompts.

The important ideas in this chapter include: