What is a Concept and how does it relate to Facts, Principles, and Procedures?

How do you identify instances of the Concepts learning domain?

Why are examples important when teaching Concepts?

Why is the range of a Concept important?

What strategies are appropriate for presenting content in the Concepts learning domain?

How do you create practice sequences for the Concept domain?

In this chapter, you will learn about teaching concepts. The term "Concepts" has a specific meaning for instructional designers. For instructional designers, the term is not synonymous with an idea or a notion. An idea is a unit of thought, it is what you are thinking about, while a concept defines a category or class of individuals. Concepts allow you to treat different entities the same. This function is enormously useful. In fact, we would not be able to think without this ability.

A Concept is a classification of entities that share the same features or attributes, such that you can consider them a group. Rand (1990) suggests that Concepts can be defined as "the mental integration of two or more units which are isolated according to a specific characteristic(s) and united by a specific definition" (p. 10). Our ability to regard separate units as members of a class allows us to conserve our cognitive resources, it allows us to make inferences and predictions (Hunt, 1962; Rosch, 1999).

For example, we have the concept "dog." The "dog" label allows us to identify Great Danes, Beagles, and Poodles as being of the same class. Without the ability to group these separate entities, we would have to treat each as being unique. If we have mastered the Concept of dog, we can muster a set of expectations that allow us to reduce our cognitive efforts. The result is that we can use our limited cognitive resources to deal with aspects of the situation that are truly different. For example, say you come across a large dog rushing toward you in a park. Normally, any large object rushing at you would be cause for concern. However, you have attained the concept of "dog," you have a certain set of expectations. One chain of reasoning that you might have that is associated with the concept of "dog" is that:

| IF the entity is a dog, THEN check its tail, |

| If the tail is wagging, THEN it is likely that the dog is playful/friendly. |

With this information, you can then accommodate your behavior appropriately. Perhaps instead of running away in a wild panic, you will assume a more open, yet guarded stance. The information that your conceptualization has provided you has assisted you in selecting your response to the situation.

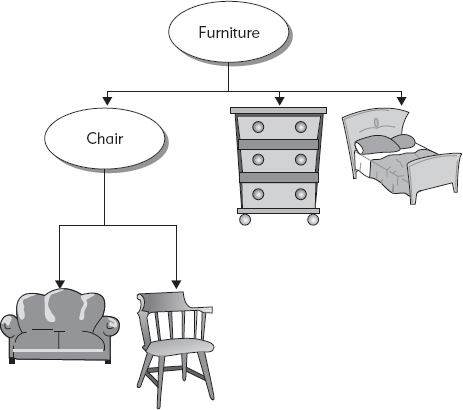

All Concepts are hierarchical in nature. For example, the Concept "furniture" can be broken down into the sub-concepts chair and table. Further, the sub-concept "chair" can be broken down into the sub-sub-concepts stool and sofa. Figure 9.1 demonstrates this type of conceptual relationship.

The point is that there is always a relationship among Concepts. These relationships manifest themselves in three primary ways: super-ordinate, subordinate, and coordinate. In Figure 9.1 the concepts chair, dresser, and bed are all coordinate to each other, while being subordinate to the concept furniture and while being super-ordinate to the concepts sofa and captain's chair. In this way, it is easy to see that any particular Concept is a "kind of" some other concept (Merrill, 1983). Since Concepts are always related to something else, it is very efficient to learn them. Once you learn a concept, there are an infinite number of instances that you now can recognize as being a member of that category.

These relationships enhance our ability to retain and comprehend instructional material. In fact, one of the best methods of determining whether material is conceptual in nature is to determine whether it can be placed in a hierarchical structure.

Learning Concepts is a matter of distinguishing them from one another. Unfortunately, making this distinction is not easy and requires a number of integrated strategies, including exposure to definitions, attributes, prototypes, examples, and structures. It also must be recognized that assessing concept attainment involves a unique challenge. We must determine whether a learner has mastered the concept by his or her ability to classify and not memorize.

When teaching Concepts, you will have to make a decision as to whether you follow a direct or discovery strategy. The most straightforward method is the direct strategy that requires you to provide the learners with a definition and follow it up with examples. This is called the rule-example strategy and is an example of deduction, which allows the learners to draw conclusions based on the premises (definitions). The reverse strategy is inductive, which consists of reasoning from detailed facts to general principles. The inductive strategy would be to provide the learners with a set of examples and see whether they can produce a definition by recognizing the commonalities. The first strategy is particularly useful for occasions when time is short. The induction strategy is discovery-centric and is more appropriate when time is not an issue and depth of processing is important.

Concepts, unlike facts, cannot be merely memorized; they must be understood and comprehended. Understanding and comprehension must be demonstrated for one to be confident that a learner has attained a concept. A demonstration must include a learner correctly classifying examples that have not been previously encountered. Un-encountered examples ensure that that a learner has not merely memorized the association between an instance of a Concept and the Concept's label. It may be tempting to re-use examples in an assessment that were used in the instruction itself; however, that would result in an invalid assessment.

One of the most difficult things about making quality assessment items for concepts is that you have to be sure you are asking the learners to demonstrate the ability to categorize. For example, the following questions demonstrate both appropriate and inappropriate questions for Concepts:

View the following three films: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly, A Fist Full of Dollars, and High Plains Drifter. Identify the primary protagonist and antagonist in each film and describe why you have classified each as such.

Conceptual presentations can be are taught using three types of strategies: (1) attention management, (2) cognitive load management, and (3) structural management that align with sensory memory, working memory, and long-term memory.

Figure/Ground. To learn a Concept, the learner's attention must be focused on its attributes. Often, attributes are declared as part of a definition. Learners need to be exposed to definitions as a first step in being able to distinguish concepts from one another. A key to a quality definition is to provide the learners with a list of attributes. These attributes should be classified as critical or optional. A critical attribute is one that must be present for an entity to qualify as a concept. Optional attributes are often helpful, but also may lead to misconceptions. For example, if the color red is used as an attribute for the concept "apple," several problems could result. Although, the color red is more often than not associated with apples, it is not the case that all apples are red; green and yellow apples certainly exist. If the color red is treated as a critical attribute, then the Concept will be inappropriately limited in scope and thus limited in usefulness and may ultimately result in a number of misconceptions.

Here's another example. Examine the following definitions of furniture:

The movable articles in a room or an establishment that make it fit for living or working

Furnishings that make a room or other area ready for occupancy

The movable objects, which may support the human body, provide storage, or hold objects on horizontal surfaces above the ground

In each case, moveable, for human use, and horizontal might be considered critical attributes, while size, shape, and color would not be. Neither would be the number of legs. Furniture is often raised off the ground through the use of supports; however, we can conceive of a piece of furniture that does not have this type of support (e.g., beanbags or hammocks).

To teach a Concept, great care has to be taken to ensure that the definitions chosen are as clear and unambiguous as possible. It is also helpful to recognize that dictionaries, the most prominent sources of definitions, rarely claim to be authoritative; rather they attempt to provide a definition based on the historical use of a term. This can be seen most profoundly in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which provides not only a definition but also the historical context of a term.

The OED's definition of furniture states:

Movable articles, whether useful or ornamental, in a dwelling-house, place of business, or public building. Context: 1816 J. SCOTT Vis. Paris (ed. 5) p. lv, The groups of poor peasants flocking in, with cart-loads of furniture present very distressing spectacles. 1866 GEO. ELIOT F. Holt (1868) 10 There was a great deal of dinginess on the walls and furniture of this smaller room.

This context should assist the learner in identifying the range and scope of any concept.

To master learning objectives in the conceptual learning domain, learners must have a clear idea of the requirements that Concepts demand. For example, it is common for learners to memorize a definition and assume that they have mastered a Concept and then, when they are asked to identify an un-encountered instance of the Concept, they may be unable to do so. To reduce learners' cognitive load, they should be informed of what the conceptual learning domain requires for mastery.

Objectives for the Concept learning domain include action verbs such as categorize, classify, discriminate, generalize, and separate, among others. For example, the following list illustrates conceptual learning objectives:

The learner will be able to classify, correctly, sample rocks as igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic.

The learner will be able to categorize, correctly, a set of governments as being oligarchic, monarchic, or republics.

The learner will be able to sort, appropriately, paintings in the Impressionistic style from those painted in the Expressionistic.

The learner will be able to design a house in the Georgian style and have it recognized as such by a panel of architectural experts.

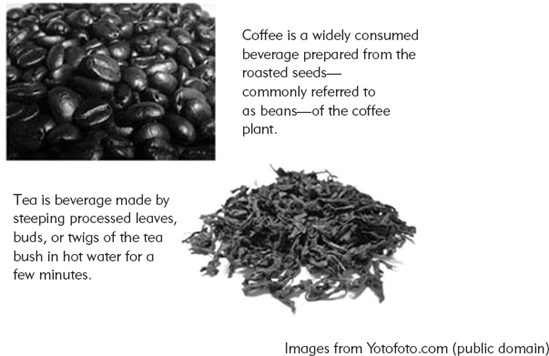

Reducing cognitive load will assist the learners in using their working memory effectively and efficiently. Concepts require the learners to integrate definitions, attributes, and examples together. It may be too much of a burden if they are asked to keep track of these elements mentally. It is far more effective to present these elements on the same screen strategically so the learners can see and refer to them in an instant. For example, if you wanted the learners to be able to distinguish "coffee" from "tea," you would want them to see the definitions and images of both at the same time. Those aspects of the lesson might be presented as in Figure 9.2.

Concepts are described by Facts. For example, the concept "verb" is defined by the statement, "a word showing action, movement, or being." The definition itself is considered a Fact. However, the definition does not exhaustively explain the Concept. The Concept "verb" is completed by a series of examples and non-examples. Concepts are classifiable and relatable to other concepts in a hierarchy.

Just as Facts are elements of a Concept description, so are Concepts elements of Principles. Principles describe how a set of Concepts change and modify one another. For example, the equation of Ohm's law (watts = volts X amps) is a Principle that demonstrates how the Concepts of watts, volts, and amps relate to one another. If the learners have some knowledge of learning domains, they will be better prepared to focus the cognitive resources on the task at hand.

Because conceptual knowledge is hierarchical by its nature, one of the most important instructional strategies is to provide the learners with the knowledge of where a Concept exists in relation to others. Every Concept exists within a structure. These structures can be very helpful to the learners in generalizing and discriminating between and among Concepts. The structure is often just as important as the Concept, and the more detailed the structure is, the more likely it is to be retained and retrieved (see Figure 9.1).

Unfortunately, because of the limitations of language, even the best definition is rarely sufficient to fully communicate the range and applicability of any Concept. In fact, most dictionaries provide an example of a term to assist in clarifying this ambiguity.

This is particularly important in reference to abstract concepts. Abstract concepts are those that do not have a physical presence. For example, the Concepts justice and democracy must be defined in terms of other Concepts, each with its own idiosyncratic connotations. In contrast, concrete Concepts are things like furniture, automobiles, and luggage. For example, justice is an abstract Concept. It can be defined as:

Justice: the ideal, morally correct state of things and persons.

To clarify the definition, an example is offered:

Justice: (1) Fair handling; due reward or treatment. Ex. My grandmother gave both my brother and me a basketball for Christmas because she wanted to be fair. (2) The administration and procedure of law. Ex. The defendant, although unpopular, received an attorney to assist him when he made the request.

To further clarify a particular Concept, one needs to provide a series of examples. Examples do the job of showing, while definitions to the job of telling. The two together give the learner a more comprehensive understanding of a Concept. Perhaps the most important instructional principle with regard to learning Concepts is to provide many examples. The more examples, the better the learning experience. It is also critical that the examples selected show the complete range of the Concept. If, for example, you are teaching the Concept of "bird," you should include examples such as the penguin and the humming bird. These examples demonstrate how widely the concept can be applied.

It is also equally important to show examples that do not qualify for inclusion as a member of the Concept in question. These "non-examples" help the learners appropriately limit the scope of application of the Concept. For example, a bat might be mistaken for a bird because it has several of the characteristics of birds. To explicitly point out to the learners that bats do not qualify as birds will help them make the distinction.

Non-examples help eliminate misconceptions. Misconceptions are a result of learning experiences, particularly of informal learning experiences, that leave the learners with incomplete or inadequate information on what does or does not constitute an example of a Concept. Often, in such cases, the learners are exposed to a narrow range of examples that encourage them to under-generalize the application of the Concept. Experience is often the best teacher; however, it is also the source of superstition and misconception.

There is evidence to suggest that the brain does not work directly with definitions of Concepts. Instead, the brain constructs a prototype (a standard or typical example) to represent the Concept. The prototype is the "best" example in that it is common and its attributes are easily identified. Providing the learners with a prototype can assist them with constructing their own internal representations. For example, a robin might be used as a prototype for the concept "bird" (Figure 9.3).

The prototype tends to be the most stable representation of a Concept and, in fact, studies have shown that learners can make a connection to an example of a Concept faster if it is closer to the prototypical example. Special care needs to be taken to prevent the learners from "regressing" to the prototype. When this type of regression occurs, the prototype is retained in the mind while the broader examples are lost in memory. To prevent this, you should provide the learners with a broad range of examples shared on multiple contacts over extended period. One of the beneficial things with Flash-based instruction is that it can be revisited at any time and connecting with instruction on a continual basis helps learners' long-term retention.

Practice sequences attempt to remove or fade support for the learner. Each type of management strategy has its own unique sequences. Table 9.1 demonstrates a sample of how these sequences might be implemented. It should be noted that rarely would all of these sequences be necessary to achieve any particular learning objective. This table repeats the Concept lesson presented in the Practice Sequences chapter.

Table 9.1. Practice Sequences for the Concept Learning Domain

Initial | Intermediate | Exit | |

|---|---|---|---|

Attention management: Modality | Task 1A: Concrete and Familiar: Which of the following expresses the idea of a vector quantity?

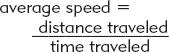

| Task 1B: Concrete: The scenario below reflects which quantity concept? While driving to the store, Anne traveled a total distance of 4.4 miles. Her trip took eight minutes. What was her average speed?

| Task 1C: Abstract: Which of the following expresses the idea of a scalar quantity?

|

5 meters is an example of a sc___ar quantity. | The well is 20 meters from the farm house on the right side. This is an example of a V_____ quantity. | A vector quantity has both ______ and ______? | |

Cognitive load management: Learner Action | Recognize: Which of the following is an example of a vector quantity?

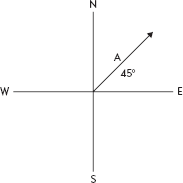

| Edit: Modify the statement below so that it is a scalar quantity. The train was running at 35 miles per hour and heading North. | Produce: Make a sentence describing the quantity in this picture.  |

Structural management: Support | A vector quantity has both direction and magnitude. For example, a stone dropped off a cliff has a trajectory and a speed. A computer disk has 1 gigabyte of memory. Is this a vector quantity? | A vector quantity has both direction and magnitude. A rocket is shot up into orbit. Is this an example of a vector quantity? | You are told that light travels at 299 792 458 m/s. Is this an example of a vector quantity? |

The important ideas in this chapter include:

This chapter described the Concept learning domain.

The nature of a Concept and its relation to Facts, Principles, and Procedure are explained.

The hierarchical nature and relationships of one Concept to another are also clarified.

Attention management, cognitive load management, and structural management presentation strategies are explored.