What is the difference between information and instruction?

What is the value of practice?

What is a practice sequence?

What role does support play in practice?

What is the theoretical foundation for developing practice sequences?

What type of feedback do learners require?

Instruction should be designed to evaluate and document learner activity. This book concentrates on practice-based activities that lend themselves not only to keeping the learner actively engaged but also provide evidence of a learner's progress. Unfortunately, most online learning designers do not emphasize providing feedback. Learners need feedback to confirm their understanding. Technologies such as static web pages, podcasts, and videos merely present information. A "page-turner" type of training only delivers information and does nothing to confirm that learning has occurred.

It is critical that the learners be active, and to be active they must engage in practice. There is no such thing as a passive learner. If a learner is truly passive, then he or she is not learning anything. Since instruction is a communications event, it requires both a sender and a receiver. Each partner participating in a communication event must confirm that the instructional message has been understood. Confirmation needs to come in the form of performance. Asking learners whether they have learned is rarely a productive exercise; most people simply do not have the ability to judge their level of understanding. A performance provides unambiguous evidence that learning has occurred.

By adding practice sequences, you can transform an information-centric learning model into an interactive and active one. To implement practice sequences successfully, a designer must learn how to analyze and separate instructional tasks into subtasks that concentrate the learner's attention, enable a performance, and allow for the presentation of targeted feedback.

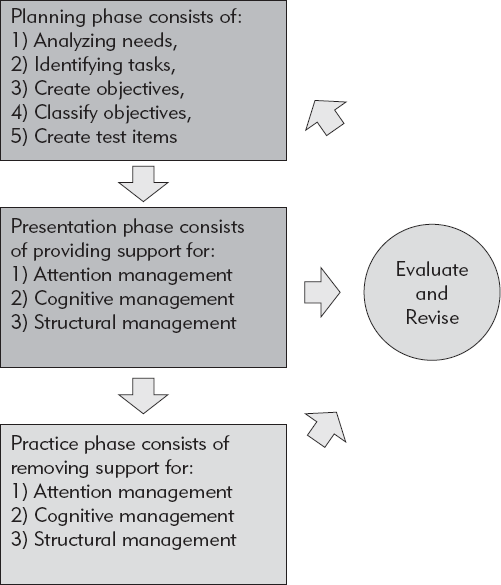

In Figure 4.1, you can see that Practice is the final phase in the design process. Practice sequences are the result of careful planning and follow the presentation of content to the learner. Practice-sequences have their own attributes that, in many respects, may be counterintuitive. It is important to note that practice sequences, like their presentation strategy counterparts, are aligned with the three types of memory from the human information-processing system. However, practice sequences have the reverse purpose. Presentation strategies attempt to manipulate and augment information to support its assimilation with each phase of the human memory system. Presentations add support to make content more comprehensible, while practice sequences seek to strategically remove that support until it is no longer needed.

As we will see, numerous choices have to be made to develop an instructional intervention, and those choices can either be the logical result of a carefully considered outcomes or they can be made capriciously. The road to quality comes with careful consideration.

The Internet has made the distribution of information easier than ever. It is tempting for many designers to simply present information and call it instruction. But presenting content is only one element of effective instruction. A good instructional designer knows that information is not equivalent to instruction. A complete instructional event must provide learners with opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge and to do so in a logical sequence. These interactions are called practice.

Imagine spending hours reading text on the screen without knowing whether your effort is helping you reach your learning goals? In fact, it is difficult to find examples of online learning that do not follow this information-centric paradigm. This is unfortunate because tools like Flash are readily available that can make practice sequences easy to implement. Instruction must require learners to perform and receive feedback on the appropriateness and quality of their performance.

Instructional software based on an information-centric design model is called a "page-turner," that is, a digital book. Unfortunately, there are few advantages to reading text digitally and many disadvantages. In most cases, learners prefer to read such material in a traditional format, like a book. Reading on the screen is still difficult. Electronic text strains the eyes more than text on paper, and books are generally lighter and easier to read comfortably. The biggest advantage that computers have over paper is that they can be interactive. If online learning is not going to be interactive, then there are few reasons to justify being online at all. Unfortunately, most online learning designers do not take advantage of these opportunities.

Instruction, at a minimum, should include learner goals, information presentation, practice, feedback, and learner guidance (Merrill, 1997; Merrill, Drake, Lacy, Pratt, & ID2 Research Group, 1996). These later elements, unfortunately, require a different set of skills beyond the presentation of information. Often those called on to develop instructional materials (technical writers, multimedia specialist, and others) are not familiar with these skills. Technical writers, for example, are concerned with clarity not evidence (Rosenberg, 2000). Learners generally require assistance that helps them to focus on outcomes, reduce cognitive load, provide practice and feedback (Rosenberg, 2000).

Quality instruction must do three basic things: (1) it must present information, (2) it must provide practice opportunities, and (3) it must provide appropriate feedback (Sivasailam, 2007). When information is presented to the learner, it is critical that great care be placed on making the content clear and that the content tie directly to goals and objectives. However, the act of communication requires more than a presentation; you must provide opportunities for the learners to demonstrate their understanding. Learners must demonstrate that they have not only comprehended the message but that they have integrated it into their cognitive structures.

Learners must have an opportunity to provide evidence that they have acquired the knowledge in question. In most cases, some sort of overt performance is required. Without such a performance, learners can have a false sense of knowledge. Learners, and in fact people in general, have an enormous capacity to delude themselves about what they know and what they do not know. One of our main jobs as instructional developers is to not allow these delusions to persist. You can reduce the chances of self-delusion by careful design. Skill, the capacity to do something well, must be free from delusion. The term "practice sequence" is used to describe activities that promote skill.

A practice sequence is much more than endless repetition. Spending hour after hour on an activity such as playing the piano may not necessarily result in becoming a better piano player unless the practice is deliberate and sequenced. A practice sequence is methodical and involves specific activities followed by feedback. It has been said that "Practice doesn't make perfect; perfect practice makes perfect." Without a sequenced practice with feedback, learners may not be enhancing their knowledge or skills.

A practice sequence implies a progression, not merely repetition. When you are developing a practice sequence, you should require the learners to perform parts of a task or subtask before they are asked to produce a complete performance.

The rationale for this is that misconceptions and misunderstandings are easily targeted and re-mediated. A practice sequence makes it easier for a designer to identify a learner's deficiencies. You must make a number of decisions, including how large each practice segment should be, how much assistance should be provided in each segment, what type of performance to require, what to do in special cases, and what type of feedback to provide. You must logically assemble these elements together to create a logical sequence of practice.

Finally, a practice sequence must provide feedback to the learners. Such feedback is most valuable when it is tied directly to performance. The sooner feedback can be provided to the learners, the more effective it will be. The learners should not have to wait to discover whether their performance was adequate. The goal is to produce a system that completes and confirms the communication cycle.

You cannot present information without including practice and feedback and creating a consistently successful learning experience. Practice and feedback are key elements for turning information into instruction. You must overcome the presentation bias by internalizing that information is not instruction.

Practice-centric design means that learners not only receives feedback on what they do not know, but they develop a sense of confidence in what they do know, which translates into actionable knowledge. Learners' confidence in their ability is a strong predictor of their performance. The best way to become confident is to have performed in a manner that indicates mastery (Galagan, 2003). A practice-centric approach also reduces the problem of learners assuming mastery when the assumption is not warranted. Learners who overestimate their knowledge can be counter-productive in every work domain. Over-confidence in one's knowledge is a result of learning that does not provide adequate practice opportunities with high-quality feedback.

Designing practice sequences requires designers to evaluate the utility of each sequence based on the results that it produces. The goal is to select a sequence that creates instruction that is maximally efficient, effective, and appealing. To ensure that you have selected the optimal practice sequence, you will have to conduct a series of user tests. Develop a practice sequence in such a way that a natural progression of activities is presented to the learners that is appropriate with their current knowledge and skill levels.

When creating sequences, your initial goal is to create practice opportunities that provide support to the learners and to then to remove, strategically, that support. In this way, the learners can successfully complete tasks with less and less support. Some learners and some content only require simple sequences, while others require sequences that are more complex.

Initially, practice sequences may provide the learners with a large amount of support guidance, perhaps including detailed explanations and hints. Then ask the learners to generate responses while being assisted with that extra information. The next step is to remove some of the supporting information and have the learners respond again. This process continues until the learners are able to respond without any assistance at all.

The idea of practice sequences emerges in a number of instructional theories. Vygotsky (1978), describes the difference between a novice learner in a subject area and an accomplished learner as "the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers" (p. 86). The distance that Vygotsky describes is his "Zone of Proximal Development." This distance is bridged by building appropriate practice sequences.

The same learning principle can be described in behavioral terms as providing cues and fading cues (Gropper, 1974; Skinner, 1953). By fading cues, a response can be transferred from one stimuli to another. Cue management can be considered a form of scaffolding, a process of providing instructional assistance and guidance (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). At times scaffolding may be limited to providing resources and advice, while other tasks demand a carefully crafted sequence of practice activities.

When designing an instructional intervention, one must decide how much scaffolding is required. Because each learner is an individual with an idiosyncratic history, perhaps the most important step is to ascertain what the learner already knows (Ausubel, 1963). Knowing a learner's state of prior knowledge is an important step in deciding where to start him or her in a practice sequence. If you place a learner in a stage of a practice sequence that he or she has already mastered, then it is likely that the learner will become bored and the activity will quickly become tedious. User tests can help identify the prior knowledge of typical participants (Angelo & Cross, 1993) and thus help you to design an appropriate set of sequences.

It is usually beneficial to start out with sequences that are more detailed. As a designer, you have a number of variables that you can manipulate. For example, you could modify the size of unit of performance, the degree of contextual support or cues provided, the type of actions the learner is required to engage in, and the amount of repetition. A sequence with large steps between practice events may confuse the learner, while a sequence with small steps between practice events may lead to the learner becoming bored. These interventions will be discussed in the following sections.

When designing a practice sequence, take great care in examining learning goals and objectives. At this stage, it is critical that the intervention be congruent with the learning objectives. The more detailed the objective, the easier it is to achieve maximal congruency and consistency. For example, the learning objective:

Given a pair of binoculars, on night with sky visibility at 90 percent, within thirty minutes, the astronomy student will be able to identify and list the relative coordinates of the planets Mars, Venus, and Jupiter on at least two out of three separate viewing nights.

may be placed into a practice sequence by first telling the students a range of plausible coordinates for each planet and then widen the range of coordinated until the students are responsible for identify coordinates independently.

An important challenge when designing practice sequences is to make difficult content easier. Some content is inherently difficult and although there is a degree of subjectivity as to what is difficult, difficult material generally has some common attributes. Some content is hard; it does not merely seem hard. For example, learners may find themselves having a difficult time with mathematics. They may view themselves as mathematically challenged.

However, evidence is increasing that the more likely culprit is that the learner has not developed appropriate cognitive strategies for dealing with the subject (Tobias, 1993). Often these learners do not have experience with the material. In most cases, the more experience one has with a subject, the easier it is to learn new things about it. Ausubel (1963) describes this phenomenon as prior knowledge influence and identifies it as the key to learning.

Apart from a learner's subjective and personal experience with content, there are also some objective criteria for determining whether content is difficult. As in the case of mathematics in general, abstract content is initially more challenging than content that is concrete. Even though a topic may be initially difficult, we can provide support to the learners to make the task easier.

Material that is inherently "hard" is challenging because it has a set of characteristics that make it that way. These characteristics include (1) the degree of similarity to other material, (2) the number of properties something has, (3) the volume of material, (4) how similar the material is to what is known, and (5) how long between the time of learning the material and its application. All of these characteristics should be considered when creating a practice sequence.

A sequence needs to identify to what degree these characteristics are at play and then to provide the learner with practice that compensates and adjusts for that particular characteristic. Building an appropriate practice sequence is primarily a problem-solving activity whose goal is to create conditions to establish congruency among instructional goals, the content domain, the idiosyncratic characteristic of the material, and the instructional intervention.

These "challenge" characteristics make it difficult for the learners to construct appropriate associations, make discriminations, and generalize. Challenge characteristics are present in all of the different knowledge domains (facts, concepts, principles, and procedures). Specific prescriptions are presented on how to handle these challenge characteristics in later chapters on those topics. Much of the following overview of challenge characteristic is based on Gropper's (1974, 1983) instructional model.

It is easier to distinguish a fish from a mammal than it is to distinguish a cat from a dog. This is because the fish and mammals are considerably different from one another, while a dog and a cat have similar attributes (i.e., furry, mammals, four legs, domesticated). Making discriminations between two classes is easier if the attributes of the classes do not overlap. That is to say, the degree to which one class is different from another makes it easier it is to tell them apart. Likewise, it is easier to generalize when the attributes are similar to one another. For example, it is easier to identify a sparrow and a robin as being birds than it is to generalize the bird concept to ostriches and penguins. The former has prototypical attributes of birds, while the later have attributes that are relatively unusual.

When instructional content has attributes similar to other content, designers must develop more involved practice sequences. They must provide more support to assist the learners in the task. Additionally, the number of attributes can make material difficult to learn. In general, the larger the number of attributes in a class, the more difficult it is to classify an instance as belonging to that class. For example, one can define a keelboat as a sailboat that has a keel instead of a centerboard (Wikipedia, 2007). Correctly classifying a keelboat is an easier task than correctly classifying a schooner, defined as a sailing boat that has sails on at least two masts (Wikipedia, 2007). Classifying a keelboat only requires you to keep track of one attribute, an easier task that keeping track of the two attributes that define a schooner.

One also must consider the number of subclasses within a class. The more subclasses, the more difficult it will be to generalize them all under the same class. For example, there are many more types of insects within the insect kingdom than there are types of mammals within the mammalian kingdom. Thus, the variation among insects is broader than it is among mammals, which makes it more difficult to classify any insect correctly.

In general, the larger the number of associations that need to be made, the more difficult the task. For example, all things being equal, a list of twenty vocabulary words would be more difficult to learn that a list of ten words. Likewise, a longer procedure will be more challenging to learn than a shorter one. For example, the safety checklist for a rowboat is considerably shorter than a checklist for a jet airplane; thus learning the airplane checklist will be a more challenging task.

Not only can similarity of attributes make some material more challenging, but so can the similarity of responses required. If a child chases a ball into traffic on a rainy day, a driver will have to respond quickly. However, the appropriate response will depend on whether the driver is operating a vehicle with or without anti-lock brakes. In a vehicle without anti-lock brakes, the appropriate response is to pump the break pedal quickly, but in a vehicle that does have anti-lock brakes, the appropriate response is to press the brake hard. These two responses compete with one another because they are so similar. This task is difficult and likely will require more practice than responses that do not compete with others.

At the same time, it is difficult to generate a response if it is substantially different from what it is associated with. For example, different languages have different words to represent the same concepts; it is easier, when learning a new language, to learn terms that are similar to those in one's native language. It is easy for a native English speaker to learn the Spanish term "el pasaporte" as an equivalent for "passport," while it may be more difficult to learn the Spanish term "el zapato" as an equivalent for "shoe."

Likewise, it can be difficult to produce a response where there is a false similarity. For example, a native English speaker when searching for the German word for "gelding" may mistakenly use the German term "das Geld," which means "money," simply because they sound similar. In these circumstances, extra care must be taken to ensure your instructional interventions take into account the ease and difficulty of making appropriate responses.

Prior learning may interfere with a learner's ability to make new, often more appropriate, associations. Sometimes this interference results in a persistent misconception. For example, studies evaluating Ivy League graduates on their grasp of basic earth-science knowledge and concepts demonstrate that many misconceptions are surprisingly resistant to change (Clement, 1987). These high-achieving students studied and learned the principles behind why the seasons change. However, upon graduation they had reverted to their previous inaccurate conceptualizations. In other words, the learning did not stick because the previous conceptualizations were so strongly embedded in the learners' minds. In fields such as science education, educators have documented topics that are likely to produce persistent misconceptions. These topics are inherently difficult and required more elaborate practice sequences. The stronger the association in a misconception, the harder it will be to replace with new understandings.

Providing context to a learner for a particular task can make it easier. Also, removing context can make the task more difficult. For example, asking a learner to describe the how to program a DVR is easier if the designer provides the learner with a remote control. The remote control reminds the learner of the procedures that are necessary for the job. The tool prompts and cues the learner.

The more prompts, cues, and hints you give a learner, the easier the task will be. The further you remove a learner from the context of the criterion performance, the more difficult it will be for him or her to perform. You, as the designer, can manipulate how much support in the form of context you provide. You may intentionally reduce contextual support, perhaps first providing context and then removing it to prepare learners to perform in a variety of circumstances.

Creating a practice sequence is essentially a matter of strategically asking the learner to perform a series of tasks. The goal with an instructional presentation was to add support to make learning easier. Practice sequences have the opposite goal; they should be designed to strategically remove support until the learner can perform without it. These sequences, like presentations, are associated with the human memory system. These tasks should be designed so that initially they are easy and then strategically become more difficult. As the learners become more proficient, they should be able to perform more difficult tasks until they are able to perform a task that reflects the terminal objective.

To design a sequence, you will have to create tasks that modify the following four variables: (1) modality, (2) scope, (3) learner action, and (4) support. It should be noted that these sequences are not always mutually exclusive. You may find that some practices can fit within a number of different categories. You will have to choose which sequences align with your particular learning goals.

To create a sequence that begins by providing support that guides the learners' attention, you should consider modality. Modality refers to the type of presentation of the practice sequence. It can include the media used or can refer to the fidelity of the presentation. A practice sequence could use sound, video, animation, illustrations, and graphics, or any combination of these. The use of these media elements will allow you to vary the level of realism presented in a sequence.

Often, a realistic practice presentation helps the learners complete the task. For example, you could make a practice task on using a computer application easier by providing realistic screen shots to show context. For other tasks, an abstraction, such as an illustration, can be most helpful. For example, when learning cell structures it is easier for a learner to identify the structures by viewing an illustration than it is to see an actual photograph taken from a microscope. A designer might begin the sequence with illustrations and end with photographs.

To create a sequence that begins by providing support that manages the learners' cognitive load, you should consider scope. Scope refers to the size of task to be practiced. Any task can be combined with other tasks or isolated into subtasks. As a designer, you must select a practice sequence that leads to criterion tasks. For complicated tasks, a small piece of the task can be practiced and eventually chained or combined together with similar subtasks; all of which lead to performing the criterion task.

An additional method for managing cognitive load is to consider the type of learner action that is required. Not only can you present content through a number of different methods but you may also ask the learners to respond in a number of different ways. You can ask the learners to identify, choose, or generate a response, all of which put different levels of cognitive load on the learners. Once again, it is important that you carefully consider learning goals and objectives. If you do not conduct a careful analysis, it is likely that you will ask the learners to provide a response that is not congruent with the overall goals.

In such circumstances, it is possible that the learners will develop a false sense of mastery over the material. They may feel confident that they have the knowledge and skills required because they can answer all of the questions posed to them; however, if these questions are not congruent with the targeted skills, then the learners do not have the necessary information to make a judgment on their skill levels. For example, if the learning objective requires the learners to produce a set of coordinates for particular planets, then it is not sufficient to have them select from a list of coordinates. The selection task is considerably easier than the production task. The selection task may be included as an initial part of a practice sequence, but is insufficient, in itself, to provide evidence that a learner has mastered the learning objective.

A practice sequence that uses learner action might be implemented as follows. The first learner action is for a learner is to identify the phenomenon in question. When presented with a task, learners merely have to provide an appropriate label. For example, a selection task might require a learner to select the label "art deco" when presented with a picture of the architecture of Miami constructed in the 1920s.

The next learner action is to have learners edit the task. Editing requires that learners modify the practice task. An editing task provides learners with substantial contextual cues, which can assist in the performance of the task. For example, learners may be presented with a picture of the Chrysler building in New York City with the statement "This building's spire is in example of Futurism architecture." The learners would be asked to edit the statement if required. If the learner were familiar with the "art deco" architectural style, they would edit the statement to "This building's spire is an example of art deco architecture."

Finally, you may ask the learners to produce a response. In a production action, a learner, perhaps with no assistance or perhaps with a number of supporting resources, will produce an answer. The production response may be further broken down into a number of question types, including fill-in-the-blank responses, short-answer, and essay questions (Flash has components to assist with each of these type of responses). This sequence begins with easy tasks and gradually asks learners to demonstrate independence.

The combinations available to a designer in creating practice sequences are limitless. For example, you could ask that the learners respond in any of the modalities previously discussed; you could ask them to provide a verbal response, create an illustration or, perhaps, a concept map, or even generate a proof or series of mathematical equations that would demonstrate their knowledge. Additionally, you could modify the standard or quality of a response. For example, for an initial practice sequence it may be acceptable for learners to respond with a misspelling. However, by the time they reach the criterion task, you may expect them to produce a correct spelling (Flash's learning components can be used to implement this type of interaction with ease).

To create a sequence that begins by providing support that assists the learners in integrating content into their long-term memory structures, you should consider the amount of support you provide. This is one of the easiest variables to manipulate. Support, cuing, or hints all assist the learners in completing the task. A cue in the form of verbal or graphic hint can be help. Once a hint is introduced, you can strategically remove it. You can fade cues, and you can diminish their resolution or you can remove them altogether. By your gradually removing these cues, the learners will begin to respond to the remaining information. Additionally, you may provide cues and then ask the learners to perform a task after a time period has passed. The time between when learners receive support and when they can perform independently is a good indication of their level of mastery.

For this example, we want to determine what type of practice sequence would be appropriate to learn the concepts "Vector" and "Scalar." We need to begin by analyzing their characteristics. That analysis would look something like this:

A vector is an object defined by both magnitude and direction; in contrast to a scalar, an object with magnitude only (Wikipedia, 2007). Both vectors and scalars have the attribute of magnitude, but differ in the requirement for direction.

Scalars are quantities that are fully described by a magnitude (or numerical value) alone.

Vectors are quantities that are fully described by both a magnitude and a direction.

Table 4.1 demonstrates how a practice sequence that manipulates different variables might be developed to teach the concepts scalar and vector. For example, you may decide to create a sequence by manipulating the modality. You could begin by asking the learners to perform Task 1A; once they have been successful with that task, you would ask them to perform Task 1B, and then, finally, Task 1C. As an alternative, you may want to give the learners an opportunity to perform the entire set of A tasks and the intermediate B tasks and, finally, the C tasks. You have an unlimited number of sequencing options; the important thing is to create a progression from easy to difficult task that gradually allows the learners to perform at levels closer to the task required by the terminal objective.

Table 4.1 only shows three tasks in each sequence, but a practice sequence could be shorter or longer. For example, learners may require several intermediate-level tasks before they are prepared to try an exit task. Likewise, learners may have mastered the terminal objective; in that case, they are ready to attempt the exit task immediately.

This example is somewhat artificial because the subject matter is not particularly complicated and, in most cases, it would not be necessary to produce such detailed sequences. However, the concepts "scalar" and "vector" do give us a chance to explore potential practice sequences. Also note that that these methods are often intermixed. For example, you could use a modality sequence at the same time as a response sequence. The tasks in the table are merely examples; you could implement each variable in a multitude of ways.

Table 4.1. Practice Sequence.

Initial Task 1A | Intermediate Task 1B | Exit Task 1C | |

|---|---|---|---|

Concrete and Familiar: Which of the following expresses the idea of a vector quantity?

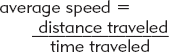

| Concrete: The scenario below refl ects which quantity concept? While driving to the store, Anne traveled a total distance of 4.4 miles. Her trip took eight minutes. What was her average speed?

| Abstract: Which of the following expresses the idea of a scalar quantity?

| |

The well is 20 meters from the farm house on the right side. This is an example of a V_____quantity. | A vector quantity has both_____and_____? | ||

Cognitive load management: Learner Action | Recognize: Which of the following is an example of a vector quantity?

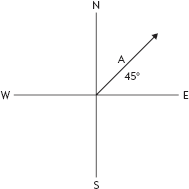

| Edit: Modify the statement below so that it is a scalar quantity. The train was running at 35 miles per hour and heading North. | Produce: Make a sentence describing the quantity in this picture.  |

A vector quantity has both direction and magnitude. For example, a stone dropped off a cliff has a trajectory and a speed. A computer disk has 1 gigabyte of memory. Is this a vector quantity? | A vector quantity has both direction and magnitude. A rocket is shot up into orbit. Is this an example of a vector quantity? | You are told that light travels at 299 792 458 m/s. Is this an example of a vector quantity? |

When using these sequences, you would ask the learners to complete the initial practice task, then the intermediate, and finally the exit task, which represents the criterion performance. At each step, you give the learners a task that is more difficult than the previous one.

Finally, you may modify the frequency of practice. The repetition variable is so obvious it does not warrant a place in Table 4.1; however, it is often an easy and productive method of increasing learning. Simply asking the learners to perform a practice sequence repeatedly can be very effective in learning domains such as procedures and facts. Time on task, or simply spending more time on difficult content and less on easier content, is an instructional strategy that consistently demonstrates positive results (Brophy, 1988). As mentioned previously, repetition should be a part of a strategically designed sequence if it is to be optimally used.

The previous description of strategies provides a foundation for creating practice sequences. However, some circumstances require more extensive practice sequences. For example, when working with the conceptual learning domain, providing examples to the learners is particularly important (see Chapter 9). You should take special care to provide a variety of examples and to vary examples as to how similar they are to the prototypical example.

It is important, particularly with examples, but applicable with any practice sequence, that you avoid repeating identical tasks. Repetition is an important principle; however, the individual tasks should vary. The idea of a practice sequence is not to pound the information into the learner's head but to create experiences that allow the learner to use the content in diverse ways.

In some situations, you may decide to have the learners perform the complete exit performance first and then begin at the initial practice task. This method is called backward chaining. This strategy is effective because you show the learners, early on, what a complete performance will look like. Even if they are not successful, they will have a model of what their goal is. Another, advanced strategy might be to ask the learners to produce a common error; by producing an error, the learners will more easily recognize it if it appears in a later performance.

Regardless of the type of practice sequence you develop, you will have to pay special attention to how and when you provide feedback to the learners. Feedback is any communication that informs learners of the accuracy of their actions (Mory, 1996). Feedback makes a practice sequences interactive. Feedback provides critical information to the learners as to whether or not they have responded appropriately. Without this confirmation, learners are incapable of adjusting and modifying their conceptions. An archer can shoot arrows at a target all day long, however, if he or she is blindfolded, the archer cannot see the target and will never improve. Only by seeing the arrow hit or miss the target will someone develop an understanding of how to improve his or her performance.

As with the practice sequence variables, you can provide feedback by a number of modalities. These modalities include simply confirming that the learner was correct or not, providing a description of the correct response regardless of whether the learner was right, and elaborated feedback that provides and explanation as to why a response was correct or why it was incorrect (Mory, 1996). You will have to decide which of the feedback options best assists your learners in meeting the learning objectives. Table 4.2 describes these options.

You may further categorize feedback by its degree of automation. You may entirely pre-program feedback, as it must be in a computer-based instruction tutorial, or you can provide unique communication, such as a conversation with a professor, or it can be a combination of both practices. When using a tool such as Flash, you can pre-program feedback through the use of learning components, or you can easily have the learner's response sent through e-mail to an instructor (see Flash guides). The method you choose to provide feedback depends on your learning goals and objectives.

Table 4.2. Methods for Providing Feedback.

The choice of feedback type is another design decision. You will have to balance the value of a particular feedback type with the time it takes to design and develop it.

Unfortunately, designing practice sequences is not as straightforward as designing presentation strategies. Practice sequences do not neatly align with the learning domain categories (Facts, Concepts, Principles, and Procedures). You will need to examine the individual characteristics of learning objectives in order to appropriately select and apply a practice sequence.

The important ideas in this chapter include:

Practice sequences allow the learners to be active participants in their own learning.

Practice sequences should be designed to remove support.

Designers have to use their creativity to develop quality sequences.

User tests are essential activities in sequence development.

Strategies for practice sequences can be aligned with the human memory system.

Appropriate feedback must accompany a practice sequence.