Foreword

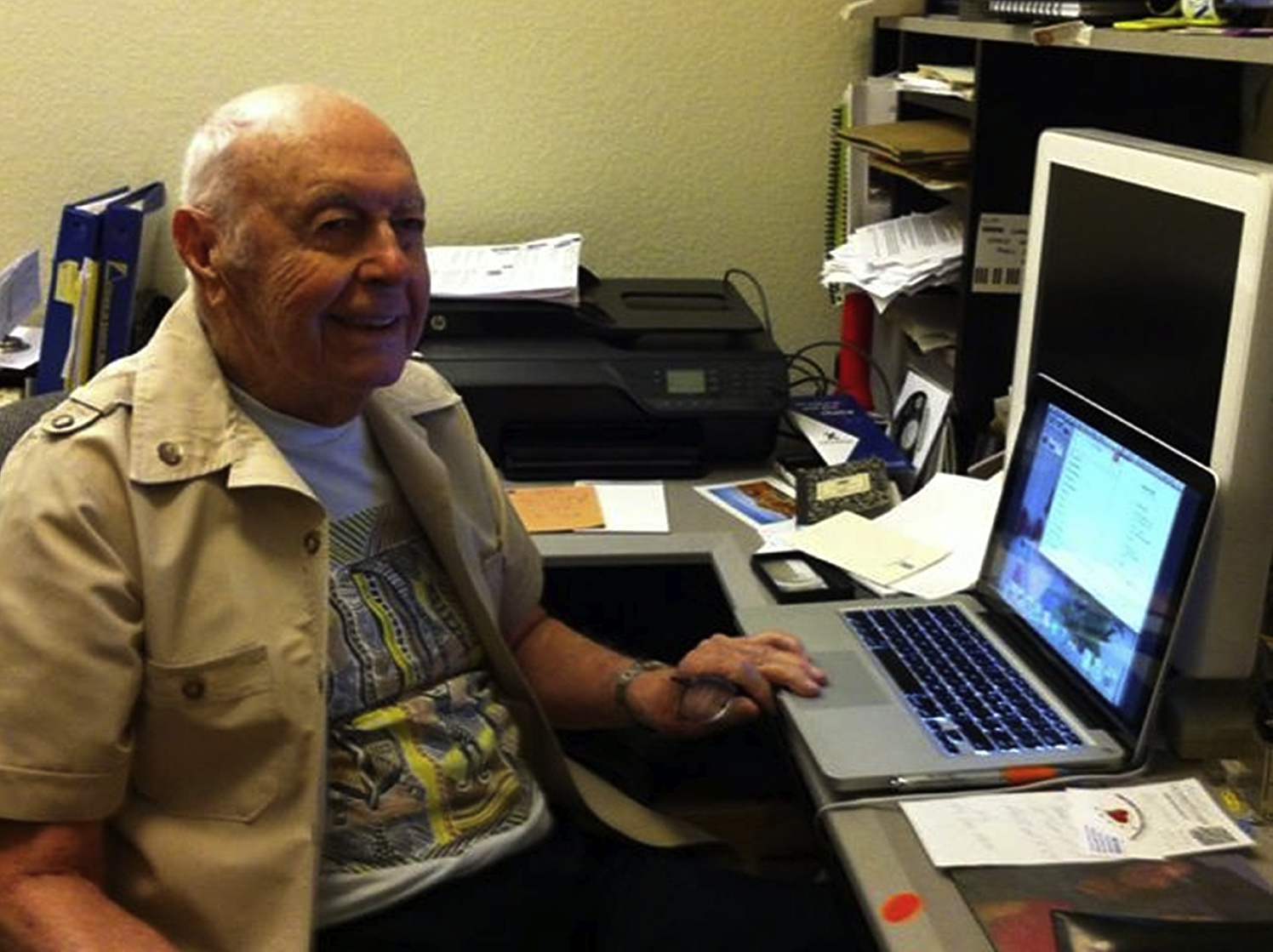

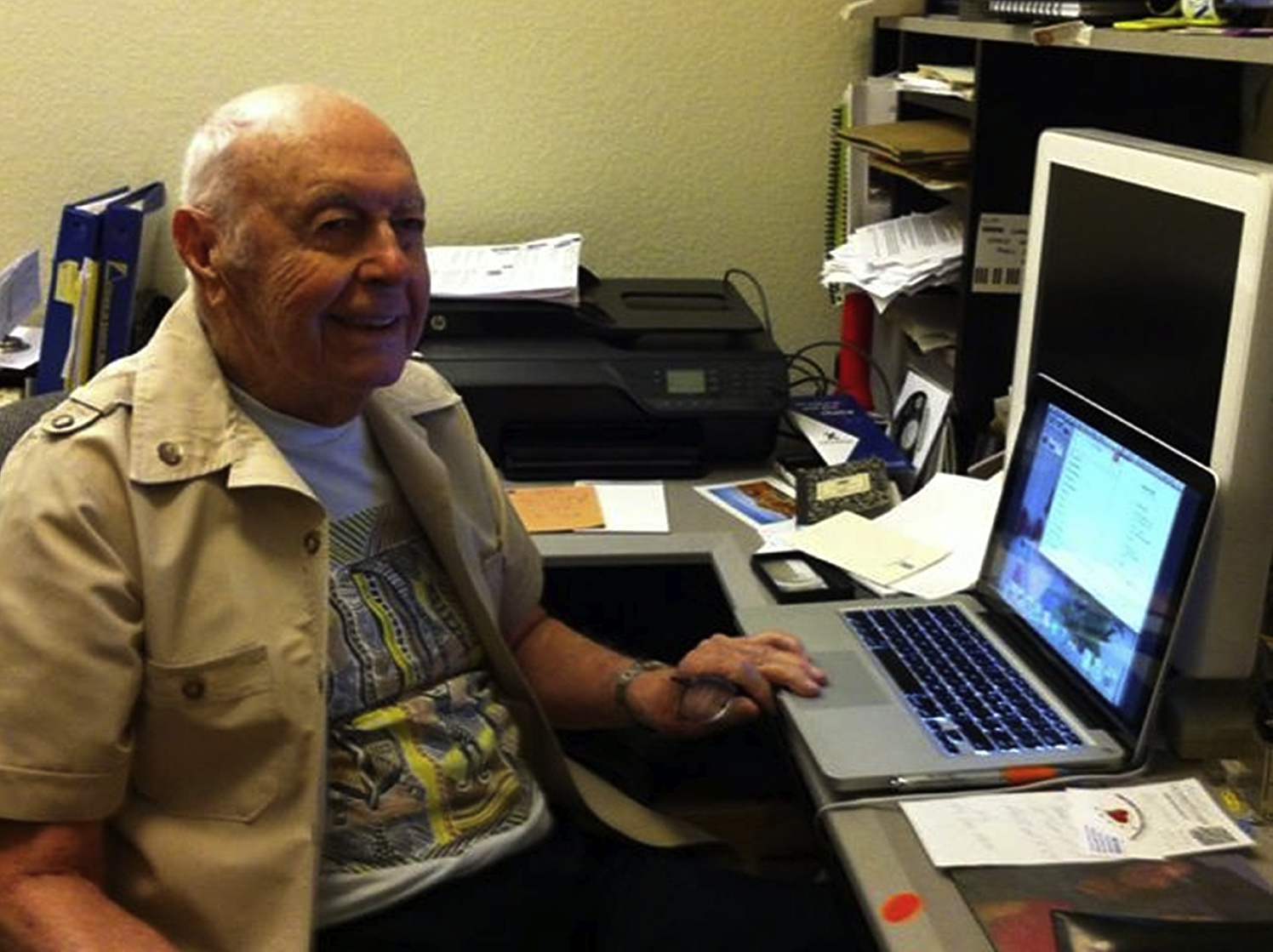

My father did his own taxes this year—which might not seem like a huge accomplishment until you realize that he turned 100 last month. He’s sharp as a tack, fit, and engaged with the life of his community and his family, just as he always has been, which he attributes to the fact that he’s always been a “cock-eyed optimist” in his own words. He uses his computer for emails and online banking and looking up information and listening to music. And let’s not forget Skyping—he loves to communicate though Skype with family and friends near and far. Recently, he was even on the cover of Live Well magazine as a poster “child” for aging well. He’s a good example of, as Jules Renard said, “It’s not how old you are, it’s how you are old.” And he is a great example of someone who is not “old” despite his 100 years.

He is struggling a bit though. See, he didn’t grow up with computers. In fact, I gave him his first computer for his 80th birthday. He’s now on his 5th one. But learning (and remembering) how to use them hasn’t always been so easy, despite his brilliance (and even though he’s using a Mac) and since his tech support (me) lives several time zones away in a different state, so he doesn’t have anyone right there to help him out when he hits snags which is frustrating.

I wish this book had been available—and used and applied—before he started using computers so they could have been designed to be more accessible for him and folks like him.

There are so many “little” things that make technology so much harder for him—“little” things that are actually arbitrary and don’t help anyone. “Little” things that aren’t so little when your body has aged and you don’t see or hear so well anymore. Or you have a tremor in your hand that interferes with your manual dexterity and eye–hand coordination. Or your memory is not so great anymore. Or your attention wanders sometimes so you’re more easily distracted. Or you find it harder to figure out what’s the most important thing on visually cluttered screens. Or your joints hurt from arthritis which makes it hard to type. Or all of the above. At the same time. I’ve seen, for instance, that it’s hard to open a pull-down menu and select the right option if it’s hard to see and you have trouble controlling the mouse. And then I realize that even I have trouble with that sometimes.

Older adults like my Dad may find that the sum total of all these small “insults” makes them feel stupid and incompetent. For many older adults, this can cause them to shut down altogether, claiming they “don’t do computers—that’s for kids.” Believe me, I’ve heard older folks who live around my Dad say exactly these words. Especially because older adults are increasingly segregated from the larger community in many parts of the world, this is tragic because computers can help them stay engaged and informed and entertained. And loved by their far away families and friends.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

There are many ways to design devices, interfaces, and interactions to make them more accessible to older adults—and to all of us for that matter. Remember how curb cuts were originally intended to make sidewalks accessible to people in wheelchairs? And how now they also help when we’re wheeling luggage or pushing a cart from pavement to sidewalk? Many “accommodations” actually make things better for all of us.

And let’s not forget that we’re all aging and that we’ll all be elderly—if we are lucky. These things will happen to us—to our bodies—but they don’t have to cut us off from life because our technology tools don’t work for us, or because the person who designed the very app we most need to use to communicate with our grandchildren was someone who was unaware that not everyone was a twenty-something like they were and that all bodies change with time. My Dad likes to remind me of what Doris Lessing said, to wit: “The great secret that all old people share is that you really haven’t changed in 70 or 80 years. Your body changes, but you don’t change at all.”

I hope that you, the reader of this wonderful book, will see ways you can help every older person—even you whether now or in 30 years—to use technology to its fullest because it is designed with everyone in mind. To do this, read and soak up this book and learn it well. Then, get to know some elders. This goes a long way to seeing older people as, well, people which in turn makes it a lot easier to design for them. Then, design and test with older adults. Once you have done this, buy another copy of this book or loan this one to someone else—like your company’s engineers and managers—and help them see how designing for older adults is not just “being nice.” Show them how designing for older adults can help the bottom line, through better sales, more customer loyalty, and a better reputation. And remind them that they, too, are aging, and that designing for aging might just make their own lives easier in some distant future when they—and you—become Older Adults.

August, 2016

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.