Sustainability—Generating a Strategic Competitive Advantage

Is There Demand for Sustainability?

Underlying the information within this chapter is a critical assumption—there is a demand for products and services that are sustainable. There is strong evidence indicating that customers (especially in economically developed markets and emerging markets) are, in fact, demanding products that are more sustainable. Consider the following statistics:

- 54 percent of shoppers indicate that they consider elements of sustainability (sourcing, manufacturing, packaging, product use, and disposal) when they select products and stores.1

- 80 percent of consumers are likely to switch brands, given that they are equal in quality and price, to ones that support a social or environmental cause.2

- 47 percent of consumers said that they bought products from a socially or environmentally responsible company, with this percentage expected to go up to 76 percent within one year.3

In other words, consumers and business-to-business customers are interested in sustainable products and services, and in the companies that produce them. Sustainability and sustainable supply chain management are about meeting and exceeding customer needs in new, more efficient and effective ways.

Objectives

- Understand how leading companies are taking advantage of the sustainability opportunity.

- Recognize the role of business models in making sustainability a strategic imperative.

- Appreciate the importance of developing environmental and social sustainability capacity with increased transparency.

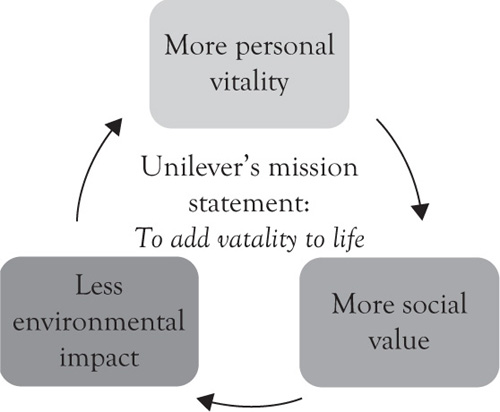

Paul Polman Transforms Unilever

Most people know Unilever, an Anglo-Dutch multinational consumer goods company. Its products include food, beverages, cleaning agents, and personal care products. It is the world’s third largest consumer goods company in terms of sales revenue (just after Procter & Gamble and Nestlé). One indication of Unilever’s success and global reach is that over 200 million times a day someone in the world is using a Unilever product. Most CEOs would be happy to live with this status quo. Not Paul Polman.

His view is to transform Unilever from a company that does well financially to a company that positively contributes to society and the environment. To undertake this transformation, Polman is shifting Unilever’s focus. At the heart of this new focus is the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan.4 The Living Plan identifies seven new key strategic supply chain imperatives, with the goal to meet them by 2020:5

Unilever’s approach to sustainability.

The key seven strategic supply chain imperatives

- Health and Hygiene: Unilever will help more than a billion people to improve their hygiene habits and bring safe drinking water to over half a billion people.

- Nutrition: Unilever will double the proportion of the product portfolio that meets the highest nutritional standards, thus helping people achieve a healthier diet.

- Greenhouse Gases: It is Unilever’s goal to halve the GHG impact of products across their lifecycle (from sourcing to product use and disposal).

- Water: Unilever aims to halve the water usage associated with the consumer use of its products by 2020. The emphasis on this objective will be greatest in those countries that are populous and water scarce, countries where Unilever expects much of its future sales growth to take place.

- Waste: Unilever’s goal is also to halve the waste associated with the disposal of its products by 2020.

- Sustainable Sourcing: Unilever’s goal is to increase the amount of agricultural raw materials sourced sustainability from 10 percent to 30 percent by 2012, to 50 percent by 2015, and ultimately to 100 percent by 2020.

- Better Livelihoods: Unilever’s goal is to link into the supply chain more than 500,000 smallholder farmers and small-scale distributors so that they can benefit by working with Unilever.

When we look at Paul Polman’s vision of Unilever’s future, we see a vision that is potentially risky. One that raises the question of whether a vision that so closely embraces sustainability (from an environmental and social perspective) can really be sustainable (as measured from a business perspective). Yet, it is a vision that Polman is now projecting onto Unilever as he looks to the developing countries to be the source not only of future demand and population growth, but also of future supply. This new vision is necessary to achieve this shift in strategic focus from the developed to developing countries.

That issue will be explored in this chapter, as we develop a deeper level of what sustainability is and is not and how sustainability can be a strategic weapon, rather than a legal constraint. This chapter is important because it is here that we establish many of the critical concepts on which an efficient and effective sustainable supply chain is built.

Understanding Sustainability

The triple bottom line (TBL) tries to address the sustainability opportunity by measuring it in accounting terms (i.e., dollars) so that management can identify those areas where it is doing a good job and areas where more work is required. First coined by Elkington (1994), this concept demands that the company be responsible not simply to stockholders, but rather to the stakeholders. Stakeholders, in this case, refer to anyone who is affected either directly or indirectly by the actions of the firm, including customers, workers, suppliers, investors, and even the environment. The goal of the TBL is to report and influence the activities of the firm as it affects financial, environmental, and social performance.

The TBL and the approach introduced in this book are not substitutes; rather, they are complements. The TBL identifies the goals to be achieved (the measurement of the financial, environmental, and social performance) but not how to achieve the balance or the best level of performance. The approach laid out in this chapter helps you better understand the options available to you. It provides you with the foundations on which the TBL can be successfully implemented and maintained over time. In some ways, the TBL may understate the focus of sustainability. The TBL views the three dimensions as areas to be measured. Although important, this view may not focus attention on what these three areas truly are—investments into three forms of capital—economic, natural, and social. As assets, these areas should generate returns that can be measured and managed appropriately to ensure positive rates of return and an integrated bottom line.

Sustainability is, in general, a poorly understood concept because it has been interpreted in many different ways. According to dictionary.com,6 sustainability has two definitions:

- The ability to be sustained, supported, upheld, or confirmed.

- The quality of not being harmful to the environment or depleting natural resources, and thereby supporting long-term ecological balance.

These two definitions highlight some of the reasons that confusion surrounds this concept. In the first definition, we can see the notion of business sustainability—developing an approach built around the business model that ensures that the value proposition (and the underlying business model) offered by the firm continues to be attractive to the key customers targeted by the firm and that this value proposition is supported by the appropriate set of capabilities. The second definition focuses on environmental sustainability. This is sustainability that deals with our ability to reduce the harm to the environment and to reduce the demands on natural resources (thus preserving them for tomorrow’s generations). These definitions interestingly overlook the growing importance of social sustainability. This is sustainability that deals with an enterprises ability to compete in the marketplace while also reducing harm to employees and communities in which the enterprise operates and engages in economic systems. While each are different, the reality is that all types of sustainability are necessary if there is to be true business sustainability—long-term viability of both the business models as well as the resources and stakeholders needed to implement such business models. This realization offers a marked contrast to what we have seen in the past and what Freedman (1970) claims “the social responsibility of business is to increase profits.”

In the past, economic, environmental, and social sustainability were seen as presenting managers with a critical trade-off. That is, if you wanted to do well from a business perspective, you had to be willing to sacrifice environmental or social performance. Conversely, if you focused on improving environmental or social sustainability, you did so at the expense of profit. This perspective can be regarded as the “OR” approach—what do you want?—better profits or less pollution? We now know this is often a misleading trade-off.

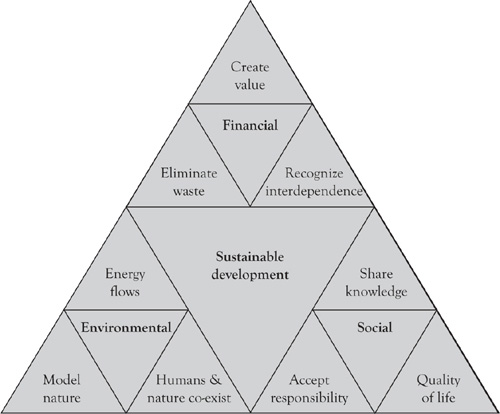

Increasingly we are seeing business, environmental, and social sustainability as tightly interlinked. That is, by focusing on environmental sustainability, we preserve resources, minimize negative impacts on people, and ensure our continued ability to satisfy customer demands—both today and into the future. These actions are not only conducive to business sustainability, but they help improve both top-line and bottom-line performance. Consequently, we can see the emergence of the “and” approach—an approach where all forms of sustainability are simultaneously attainable. Yet, it is important to note that the presence of environmental or social sustainability by itself is not enough to ensure business sustainability. The authors of this book take the view that environmental and social sustainability facilitate business sustainability. It is also this view that drives a vision of sustainability portrayed in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Sustainability and its business implications7

Source: Sustainable Land Development Initiative (SLDI) Code™

Sustainability and Its Implications for the Firm

Sustainability is attractive because it can and does affect various aspects of corporate performance and competitive advantage:

- Natural resource, energy, and operational efficiency resulting in reduced input and overhead costs, fewer regulatory sanctions, reduced waste expenses, and enhancing the ability of the firm to conserve capital for implementing long-term growth strategies.

- Enhanced ability to attract and keep better quality employees, resulting in a better ability to retain experienced workers. This prevents the loss of corporate knowledge and expertise, reduced training costs, lowers employee absenteeism, increases worker productivity, and ultimately helps to attract and keep the best talent.

- Reduced risks from mitigating higher costs of energy, water, and waste, fewer exposures to supply chain disruptions, and reduced exposure to the risk of a price on GHG emissions.

- Better financial operations can help improve relationships with investors and also make the stock more attractive to potential investors. Other benefits include lower insurance premiums, decreased borrowing costs, and enhanced access to financial capital.

- Improved revenue streams, better marketing, and communication as sustainability offers the firm a way of expanding its customer base by attracting those customers for whom sustainability is important. Such customers are often less price sensitive. Furthermore, because these customers are often better educated and earning more, they tend to buy more and frequently. Focusing on sustainability enables the firm to differentiate its products, and to improve brand image and brand equity (important corporate assets). For a growing number of firms, financial and nonfinancial (sustainability) information is now communicated into one integrated report.8

In other words, sustainability, if implemented properly, affects both the top line (increased sales) and the bottom line (increased profit) through the one-two punch of increased revenue and decreased costs. However, for us to develop a better understanding of how these concepts interact, we must first understand each concept in isolation—beginning with environmental sustainability.

Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustainability involves more than simply reducing pollution; it is a broad-based approach that focuses on reducing waste while improving performance across a TBL. The concern over sustainability has influenced buying policies and sourcing requirements found in Canada, the United States, the European Union, China, and Australia. Companies such as Alcoa, Best Buy, Dell, Steelcase, Phillips, Wal-Mart, Coca-Cola, Ford, Toyota, Unilever, Disney Entertainment, and the Inter-Continental Hotels are now explicitly considering sustainability in their planning at both the strategic and operational levels. To appreciate the commitment that some companies have made to environmental sustainability, consider the approach taken by Walt Disney Resorts.

Walt Disney is the world’s largest media and Entertainment Company, and increasingly a leader in environmental sustainability. To achieve this status, Disney has taken the following steps:

- Cutting Emissions: Walt Disney plans to cut carbon emissions by half, reduce electronic consumption by 10 percent, reduce fuel use, halve the garbage at its parks and resorts, and ultimately achieve net zero direct GHG emissions and landfill waste. Consequently, Walt Disney World has been designated as Florida Green Lodging Certified and they use an internal price on carbon dioxide emissions when evaluating projects9.

- Recycling and more: The Disney Harvest Program, founded in 1998, distributes nearly 50,000 pounds of food to the Second Harvest Food Bank every month (taken from food that has been prepared but not served at Disney’s various restaurants and convention centers). All used cooking oil at Walt Disney Resort is collected and recycled into bio fuel, as are other products that are used by local companies. Food scraps are recycled into compost that is used locally as fertilizer. The Walt Disney Healthy Cleaning Policy has the goal of minimizing the environmental impact of its cleaning products. The majority of props, vases, and containers used by the Disney floral team for events are made from reusable glass and plastics. Finally, every day, 10 million gallons of wastewater is reclaimed and used in irrigation systems and other similar applications.

- Preserving the Wildlife: When building Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, the company set aside more than one-third of the land for a wildlife conservation habitat. This habitat forms the basis for Disney’s Animal Kingdom Theme Park, which is used to educate guests on the importance of conservation and preserving the future.

Ultimately, these and other steps are part of Walt Disney’s long-term environmental strategy of:

- Zero waste

- Zero net direct GHG emissions from fuels

- Reducing indirect GHG emissions from electricity consumption

- Net positive impact on ecosystems

- Minimizing water use

- Minimizing product footprint

- Informing, empowering, and activating positive action for the environment

One strong indication of the growth and spread of environmental sustainability can be found in Table 3.1, which lists the top 51 sustainable corporations in the world. In reviewing the listing of firms, it is interesting to note that the first North American firm to make this list is Life Technologies Corporation (#15). Unilever is 51, with Johnson Controls Inc. at 64, Proctor & Gamble 66, and Baxter International coming in at 86. As we can see in the Unilever vignette, it is also becoming a strategic consideration—something that Polman is using to distinguish Unilever in the marketplace and to differentiate it from competition (e.g., Proctor & Gamble who also reports on a broad array of sustainability activities).

Table 3.1 Global 100 List—Top 51 Firms (all North American firms noted in bold)

| Rank | Company | Country | Rank | Company | Country |

1 |

Novo Nordisk |

Denmark |

16 |

Credit Agricole S.A. |

France |

2 |

Natura Cosmesticos S.A. |

Brazil |

17 |

Henkel AG & Co. KGaA |

Germany |

3 |

Statoil ASA |

Norway |

18 |

Intel Corp. |

United States |

4 |

Novozymes A/s |

Denmark |

19 |

Nest Oil Oyj |

Finland |

5 |

ASML Holding N.V. |

Netherlands |

20 |

Swisscom Ag |

Switzerland |

6 |

BG Group Plc |

United Kingdom |

21 |

Toyota Motor Corp. |

Japan |

7 |

Westpac Banking Corp. |

Australia |

22 |

Centrica Plc |

United Kingdom |

8 |

Vivendi S.A. |

France |

23 |

Koninklijke DSM N.V. |

Netherlands |

9 |

Umicore S.A./N.V. |

Belgium |

24 |

Geberit Ag |

Switzerland |

10 |

Norsk Hydro ASA |

Norway |

25 |

Roche Holding Ag |

Switzerland |

11 |

Atlas Copco Ab |

Sweden |

26 |

Schneider Electric S.A. |

France |

12 |

Sims Metal Management Ltd. |

Australia |

27 |

Sap Ag |

Germany |

13 |

Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. |

Netherlands |

28 |

Hitachi Chemical Company Ltd. |

Japan |

14 |

Teliasonera Ab |

Sweden |

29 |

Anglo American Platinum Ltd. |

South Africa |

15 |

Life Technologies |

United States |

30 |

POSCO |

South Korea |

31 |

Vestas Wind Systems |

Denmark |

42 |

AstraZeneca Plc |

United Kingdom |

32 |

Dassault Systemes, S.A. |

France |

43 |

Kesdo Oyj |

Finland |

33 |

BT Group Plc |

United Kingdom |

44 |

Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. |

Japan |

34 |

TNT N.V. |

Netherlands |

45 |

L’Oreal S.A. |

France |

35 |

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. |

Japan |

46 |

Logica Plc |

United Kingdom |

36 |

Scania Ab |

Sweden |

47 |

Suncor Energy Inc. |

Canada |

37 |

Acciona S.A. |

Spain |

48 |

Repsol YPF, S.A. |

Spain |

38 |

Adidas Ag |

Germany |

49 |

Prudential |

United Kingdom |

39 |

Tomras Systems ASA |

Norway |

50 |

Renault S.A. |

France |

40 |

Aeon Co. Ltd. |

Japan |

51 |

Unilever Plc |

United Kingdom |

41 |

Siemens Ag |

Germany |

Environmental sustainability is important to existing companies wanting to maximize the efficient use of resources and future companies who will eventually need access to the same resources. The most widely used definition of sustainability was offered by the United Nations Brundtland Commission in its report. This report stated that sustainability is “the ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” In other words, what we do today to satisfy current needs will affect the future. This is one reason that the “cradle-to-grave” approach is no longer adequate for environmental sustainability (see the Story of Stuff).11 Only about 1 percent of all the materials mobilized to serve America is actually made into products and still in use six months after sale.12 Meaning 99 percent ends up in landfills within six months. With a cradle-to-grave approach, we focus on returning waste to the ground. The problem is that this waste is essentially useless—it cannot be used to fulfill the original demand. It must be replaced by new, virgin material. It also is a missed opportunity for reclaiming raw materials and closed-loop systems (also called C2C, and if done properly, cradle to cradle to cradle). We are coming to the realization that the earth’s resources are finite. As we use more today, there is less for future generations. This realization is not new; it is just becoming more prevalent and a larger opportunity for entrepreneurs to better leverage a circular economy and closed-loop supply chain systems to find solutions to this issue.

Social Sustainability

The second element, social sustainability, focuses attention on people, specifically human rights, health and safety, and quality of life in communities. Think of all the stakeholder groups that a typical business directly affects: customers, workers, suppliers, and investors. In addition, businesses can indirectly affect the larger community and society as a whole.

Each of these stakeholder groups has their own needs and priorities (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.2 Key Stakeholders and Their Expectations

| Customers | Workers |

Good “value” for their money products that are safe Privacy and protection of personal information Honesty in marketing and sales communications Integrity in fulfilling contracts and obligations Quick response to questions System transparency, traceability |

Fair labor practices and a “living wage” that affords a reasonable standard of living Safe working and living environments (both for themselves and the community) Equal opportunities for advancement Support for social and economic developments (e.g., schools, arts, parks, charities) |

| Suppliers | Investors |

Working with like-minded firms (who share similar values) Opportunities for supplier development and improvement (learning within the supply chain) Opportunities to grow—shared success Consistent application of rewards and punishments Receiving a “fair” payment for goods and services provided |

Providing competitive returns on investments Having a robust business model so that investors can expect consistent returns over time Integrity in reporting operating and financial conditions Reduction of unreasonable risks and uncertainties (due to poor practices on the part of the firm and its operations management system) |

As the examples in Table 3.2 illustrate, managers and supply chain members need to consider the needs and demands of many stakeholders when making choices about sources, process designs, labor policies, and so on. Numerous social issues are continuously highlighted by the media, pointing out potential inequities, or even the oppressive conditions businesses and their suppliers might create, either knowingly or unknowingly. For example, in recent years the media have brought attention to the exploitation of workers and small businesses in developing countries. As a result, more and more operations managers are participating in established “fair trade” practices. It also affects how companies buy and sell products. Fair trade is an organized social movement that seeks to help producers in developing countries, thus making for better trading conditions and promoting sustainability. Through fair-trade efforts, farmers are paid a price for their products, increasing revenues. This allows them to invest in better equipment, better food for their families, and allows them to send their children to school (rather than keeping them working on the farm to support the family). Many of the farmers affected often grow commodity products such as coffee. Consider the experiences of Starbucks with fair trade:

Starbucks Corporation is an international coffee company and coffeehouse chain. It is currently the world’s largest coffeehouse company. In 2000, the company introduced a line of fair-trade products. Since then, this practice has evolved into a corporate-wide system aimed at guaranteeing ethical sourcing. To this end, it has worked with Conservation International to develop the Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) practices for coffee-buying. This comprehensive set of guidelines focuses attention on four areas:

- Product quality

- Economic accountability

- Social responsibility

- Environmental leadership

Social responsibility measures are evaluated by third-party verification to ensure safe, fair, and humane working conditions and adequate living conditions—they cover minimum wage, child labor, and forced labor requirements.

In 2011, Starbucks bought over 428 million pounds of coffee, of which 367 million pounds were from C.A.F.E.–practices-approved suppliers. The company paid an average price of $2.38 per pound in 2011, up from $1.56 per pound in 2010. According to Conservation International, this premium has enabled farmers participating in C.A.F.E. practices to keep their children in school and to preserve remaining forest on their land, while achieving higher crop performance. This program spans some 20 countries and affects over 1 million workers each year and is impacting practices on 102,000 hectares each year (where a hectare is about 2.47 acres and in this case about 393 square miles a year). In terms of fair trade, Starbucks has paid an additional $16 million in fair-trade premiums to those producer organizations for social and economic investments at the community and organizational levels.13 Fair trade is but one social movement and differentiation strategy involving social responsibility.

If you think no one is keeping track of the social dimensions of your operations and those of your supply chains, you may be surprised to find your company on a list of poor-performing firms. Numerous organizations are measuring and ranking the operations and supply chain performance of publicly traded firms. These organizations include the well-known American business magazine Forbes, and established databases of socially responsible firms such as Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini (KLD) now owned by MSCI. You can now access Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) data through Bloomberg terminals. This is the same data used in socially responsible investing indices and be used to leverage other rankings by Newsweek purposefully looking at (ESG) performance.

Among the leaders in this social dimension are firms such as Starbucks, Unilever, Nestlé, Walt Disney, Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream, Marathon Petroleum, and Delta Airlines (to name only a few). A listing of the most and least admired companies from a social responsibility perspective is in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Forbes’ Most Admired Companies “Best & Worst in Social Responsibility”14

| Most admired | Least admired |

1. GDF Suez |

1. China Railway Group |

2. Marquard & Bahls |

2. China Railway Construction |

3. RWE |

3. China State Construction Engineering |

4. Altria Group |

4. China South Industries Group |

5. Starbucks |

5. China FAW Group |

6. Walt Disney |

6. Aviation Industry Corp. of China |

7. United Natural Foods |

7. Dongfeng Motor |

8. Sealed Air |

8. MF Global Holdings |

9*. Chevron |

9. China North Industries |

10*. Whole Foods Market |

10. Hon Hai Precision Industry |

*Companies whose industry scores are equal when rounded to two places received the same rank. In cases of ties, companies are listed in alphabetical order. |

|

Deploying Social Sustainability

The social dimension of sustainability concerns the impacts an organization has on the social systems within which it operates, for example, reporting on human rights, local community impacts, diversity, and gender. The most comprehensive and widely accepted social sustainability reporting guidance is the Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI) guidelines. Within this framework, performance indicators are organized into categories: economic, environment, and social. The social category is broken down further by labor rights and decent work practices, human rights, society and product responsibility subcategories. This measurement and reporting is done within the context of a materiality assessment and resulting matrix showing the level of stakeholder concern of sustainability issues in comparison to impacts on an organization.

Performance indicators are the qualitative or quantitative information regarding firm results or outcomes associated with the organization that is comparable and demonstrates change over time.15 Disclosing firms will release information on their management approach, goals and performance, policies in place, who within the organization has responsibility for the performance indicators, training and awareness, and how the performance indicators are monitored. Examples of labor, human rights, society and product responsibility from the GRI include the following:

Labor practices are guided by a number of internationally recognized standards from the United Nations and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). For an understanding of these practices, reporting firms can draw upon two instruments directly addressing the social responsibilities of business enterprises: the ILO Tripartite Declaration Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Practices include the composition of the workforce, full-time employees, benefits and retention rates, labor/management relations, occupational health and safety, employee training and education opportunities, diversity, equal opportunity, and equal remuneration for both women and men.

Human rights practices take into account a growing global consensus that organizations have the responsibility to respect human rights. Human rights performance indicators require organizations to report on the extent to which processes have been implemented, on incidents of human rights violations, and on changes in the stakeholders’ ability to enjoy and exercise their human rights during the reporting period. Among the human rights issues included are nondiscrimination, gender equality, freedom of association, collective bargaining, child labor, forced and compulsory labor, and indigenous rights.

Society practices focus attention on the impact organizations have on the local communities in which they operate, and disclosing how the risks that may arise from interactions with other social institutions are managed and mediated. In particular, information is sought on the risks associated with bribery and corruption, undue influence in public policy making, and monopoly practices. Within social performance, community members have individual rights based on: Universal Declaration of Human Rights; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights; and Declaration on the Right to Development.

Indicators of product responsibility address the aspects of a reporting organization’s products and services that directly affect customers, namely, health and safety, information and labeling, marketing, and privacy. These aspects are primarily covered through disclosure on internal procedures and the extent to which there is noncompliance with these procedures. Reporting firms have the opportunity to provide disclosure on their management approach to customer health and safety, product and service labeling, marketing communications, customer privacy, and compliance.

This summary of social sustainability can be new and uncharted territory for many. For some well-known firms highlighted in this book, the social performance dimension is one more way to build brand. Social sustainability is still an emerging area for many to differentiate products, measure and manage typically overlooked aspects of value creation, and become an employer of choice while simultaneously building top-line and bottom-line growth.

Trends in corporate transparency and reporting are such that reporting financial performance is only a starting point. KPMG and others have demonstrated the start of integrated reporting of business, environmental, and social sustainability performance into one report.16 As we will see in this and the next chapter, the public disclosure of these performance metrics reveals a shift in corporate reporting, emerging views of sustainability, and an opportunity to leverage lean operations to realize the value created by sustainability.

Transparency

Transparency is most notable through the broad expansion of corporate reporting. Gone are the days of producing and auditing only a financial report. Sustainability reporting is the practice of measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organizational performance toward the goal of sustainable development. “Sustainability reporting” is a broad term considered synonymous with others used to describe reporting on economic, environmental, AND social impacts (e.g., an integrated bottom line, corporate responsibility reporting, etc.).17 A sustainability report should provide a balanced and reasonable representation of the sustainability performance of a reporting organization—including both positive and negative contributions. Sustainability reports based on international frameworks disclose outcomes and results that occurred within the reporting period in the context of the organization’s commitments, strategy, and management approach. Reports can be used for, but not limited to, the following purposes:

- Benchmarking and assessing sustainability performance with respect to laws, norms, codes, performance standards, and voluntary initiatives.

- Demonstrating how the organization influences and is influenced by expectations about sustainable development.

- Comparing performance within an organization and between different organizations over time.

The urgency and magnitude of the risks to our collective sustainability cannot be understated. New measurement and reporting opportunities will make transparency about economic, environmental, and social impacts a fundamental component in effective stakeholder relations, investment decisions, and other market relations.18 Increasingly, it is difficult to find an annual report that omits any discussion of the sustainability activities of the firm. Yet, we must recognize that not all firms claiming to be sustainable are operating at the same level of intensity. We argue that firms operate at one of the three levels of sustainability:

- Sustainability as public relations

- Sustainability as waste management

- Sustainability as value maximization

As we move from the first to the last, we see a broader application of sustainability (Table 3.4). We also see a different view of the dynamic relationships between environmental, social, and business sustainability.

Table 3.4 View of Sustainability Relationships

| View of Sustainability | Relationship (financial, environmental, and social sustainability) |

Public relationships |

Trade-off; You can be one or the other; focus on one dimension Environmental or social sustainability is a constraint |

Waste management |

Mixed—some trade-offs; more complementary |

Value maximization |

Simultaneity; integration You have multiple types of sustainability; Environmental and/or social sustainability is an opportunity and a strategic weapon |

However, each level must be explored separately if it is to be understood.

Sustainability as Public Relations

Firms focusing on sustainability at this level are not really committed to all three dimensions. Management ultimately believes that there is a trade-off between profit and social or environmental sustainability—to do better on one dimension, you must do worse on another. They feel that they have been forced by external pressures (e.g., consumers, government, stockholders) to show that their firms are undertaking some form of environmental program.

Such programs, when implemented, are often copied from other firms. When implemented, there is little or no modification or customization of the programs and their associated practices. Customization is important to ensure that newly-adopted practices first fit the firm’s unique corporate setting. Environmental programs also have to be extended and transformed in ways that create new value for the key customers. These programs are there so that management can point to their presence as proof of the firm’s commitment to some level of sustainability.

Sustainability as public relations is all about “show”; if you are able to dig deeper, there is little of substance behind the show. When reporting, the firm looks for whatever evidence it can find that shows the firm is securing the benefits of sustainability. When implemented, the programs tend to be superficial—focusing on the symptoms rather than the root cause of pollution. Recycling is emphasized and reported rather than pollution prevention. Investments are made in initiatives but little real progress is secured because management and corporate commitment to environmental sustainability is lacking. Sustainability as public relations sometimes manifests as “greenwashing” when stakeholders call out an organization for not truly being green.

Internally, sustainability is treated as a constraint—something that must be satisfied before the firm can turn its attention to what really is important. The programs and initiatives, when added, are often add-ons—present but poorly integrated. These programs are separate from the rest of the firm. Responsibility for environmental sustainability is not a total corporate responsibility (everyone is responsible) but rather something that is assigned to one department and few who are accountable for the programs. Performance is measured from the perspective of punishment avoidance or punishment incurred (e.g., number of fines, size of fines).

Finally, these firms are the first to drop or scale back initiatives in sustainability should the economy deteriorate (thus requiring firms to focus on cost savings) or should management feel that the external forces driving the emphasis on sustainability are diminishing. You may already know of some firms at this level of sustainability. We provide examples of more progressive firms in the next chapter as we continue exploring levels of sustainability with a focus on waste management, and value maximization in the next chapter.

Summary

This is a book about developing and maintaining the sustainable supply chain. Given the growing importance of sustainability, the goal of Chapter 3 has been to develop a thorough and well-grounded understanding of this business paradigm. In this chapter, the following points were made:

- We need a more dynamic understanding of sustainability.

- Sustainability implementation and achievement affects the extent to which environmental and social performances are viewed as complementary or as trade-offs.

- Supply chains and organizations are becoming more transparent.

- Sustainability can help with public relations, yet needs to be a strategic part of differentiation and competitive advantage.

With chapters one and two as a foundation, we are now able to move toward the challenge of developing a sustainable supply chain. As we do so, there are more foundational elements to introduce—enhancing value, along with business model integration. That is the focus of the coming chapter.

Applied Learning: Action Items (AIs)—Steps you can take to apply the learning from this chapter

AI: What companies in your own industry do you consider leaders in sustainability? Why?

AI: Search the web for social sustainability issues in your industry, does your organization have these same issues?

AI: Who is the most transparent company in your industry?

AI: Who are your organization’s key stakeholders? Why?

AI: Conduct a self-audit of your firm’s environmental and social sustainability practices.

AI: What public relations information has been issued by your firm that involves environment or social performance?

Further Readings

Eccles, R. G., & Krzus, M. P. (2014). The Integrated Reporting Movement: Meaning, Momentum, Motives, and Materiality. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Epstein, M. J., & Buhovac, A. R. (2014). Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Hawkin, P. (2017). Drawdown – The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever to Reverse Global Warming. Penguin Books.

McDonough & Braungart (2013). Upcycle. North Point Press.

1GMA/Deloitte Green Shopper Study (2009).

2Cone (2010).

3Tiller (2009).

4Ignatius (2012), p. 115.

5Ibid.

6http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/sustainability?s=t, last accessed July 2, 2013.

7SLDI (2013).

8Eccles and Krzus (2010).

9Use of internal carbon price by companies as incentive and strategic planning tool, Carbon Disclosure Project; http://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/22Nov2013-CDP-InternalCarbonPriceReprt.pdf

10Global 100 (2012).

11Annieb (2007).

12Lovins, Lovins, and Hawkins (2007).

13Starbucks (2013).

14From CNN Money, Forbes’ Most Admired Companies, the top ten and worst for social performance (2012).

15Global Reporting Initiative (2012).

16KPMG (2011a & b). Also see the book “One Report” by Eccles and Krzus.

17GRI (2013b).

18GRI (2013c).