Strategic Sustainability—Systems Integration and Planning

“We can’t impose our will on a system. We can listen to what the system tells us, and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone.”

—Donella H. Meadows

What Happens When We Get the System in the Room?

- The parent company of toy manufacturer, Lego, has invested in one of Germany’s largest offshore wind farms—a move to bolster the firm’s renewable energy consumption with goals of 100 percent renewables by 2020, and a carbon neutral supply chain.

- Praxair, a global Fortune 300 company that supplies atmospheric, process and specialty gases, high-performance coatings, and related services, voluntarily began collecting environmental key performance indicators in productivity projects. In one year, 8 percent of Praxair projects were tagged “sustainable development,” and produced $32 million and 278,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalent in savings.

- Starbucks has used Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) Practices—a set of guidelines to achieve product quality, social responsibility, economic accountability, and environmental leadership. They have even offered sustainability bonds to support sustainable coffee sourcing and leading efforts for positive environmental and social impacts on global coffee supply chains.

We next extend the definition of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) within the larger context of systems stressing the integration of financial, environmental, and social performance measurement along with management throughout a product’s life cycle. When defining the SSCM concept, we are actually introducing a paradigm shift of sustainability as not involving dichotomous trade-offs, but as an inclusive, collaborative, and integrating process for improved performance. The vignettes above are not explicitly about logistics, but the actions of Lego, Praxair, and Starbucks have supply chain impacts involving inputs to systems such as energy, the importance of metrics, and new social sustainability efforts up and down a supply chain. By the end of this chapter you will see that sustainability is not someone else’s job, but an opportunity for everyone to improve products and processes across multiple dimensions of performance with an integrated approach.

Objectives

- Review trends impacting the future of SSCM.

- See how SSCM needs systems integration to become more sustainable.

- See sustainability for the strategic initiative it is and provide an applied approach to planning for it.

Risks of Waiting: Compliance Is not Enough

Commodity volatility, adverse weather conditions (e.g. superstorms), and a range of other threats were very visible in recent years. Despite the measures taken to combat these events, the sentiment among procurement executives is that weather-related events will only continue to increase costs. The Procurement Intelligence Unit1 estimates that the Forbes Global 2000 stands to lose a staggering €280 billion from weather-related events. The research, which took into account the views of 181 senior procurement executives, also showed that the procedures aimed at reducing the impact of unexpected events are limited. The majority of businesses assume that suppliers will take responsibility for managing supply continuity with a tiny minority of firms actively deploying strategies that extend to suppliers’ suppliers.

There is growing evidence of businesses taking practical actions to embed sustainability within their day-to-day supply chain operations.2 The vignettes at the start of this chapter highlight companies and some results, but what is most needed is a vision and planning process for integrating sustainability into SSCM. This vision starts with an understanding and an integrated view of the entire supply chain from raw material extraction to disposal or opportunities for closed-loop, cradle-to-cradle (C2C) systems. The vision is supported by understanding the current state of the organization, developing creative solutions, and prioritizing options. There is now a need to focus on the integration of performance measurement, embedding cost effectiveness, a focus on customer service and simultaneous sustainability improvement within the total cost of ownership. For example, when looking for new performance measures, start with carbon dioxide (CO2) and look into other GHG emissions. Why carbon dioxide? There is already a price on it and several countries have trading platforms for CO2. China has six trading platforms. As previously mentioned, CO2 represents waste from a process that adds no value to a product or process. Calculate the carbon footprint of your own operations and those of your supply chain and take steps to incrementally integrate CO2 into the business case for projects with goals for CO2 reduction. Finally, when making the business case for new sustainability projects, deploy the most cost-effective and proven technologies. Deploying your vision of sustainability requires a systematic approach. Those organizations that take the lead in developing innovative supply chain strategies and then proactively embed sustainability within their operations will be the most likely stay ahead on supply chain performance over the longer term. What is your vision?

Trends to Watch

Evidence of changing customer expectations and sustainability moving up the corporate agenda was confirmed by a KPMG global survey of 378 senior executives,3 which found the following:

- 62 percent of firms surveyed have a strategy for corporate sustainability with 23 percent of firms in the process of developing a plan.

- Primary drivers for sustainability are resource and energy efficiency, with brand enhancement, regulatory policy, and risk management still remaining key drivers.

- 44 percent of executives in the study see sustainability as a source of innovation, whereas 39 percent see sustainability as a source of new business opportunity.

- Firms are increasingly measuring and reporting their sustainability performance and businesses want a successor to the Kyoto Protocol.

- 67 percent of executives believe a new set of rules is “very important” or “critical” to have a clear road map for sustainability with corporate-lobbying efforts pushing for tighter rules.

With increasing scrutiny of corporate carbon emissions, freight and transportation providers now have every opportunity to strategically impact and realize sustainable value from their operations. Emissions from freight in the United States are projected to increase by 74 percent between 2005 and 2035. China is expected to increase its use of freight transportation fuels by 4.5 percent a year from 2008 to 2035. Global freight emissions are predicted to increase by 40 percent in the same period.4 Given this growth, we paradoxically have significant influence over the carbon footprint of supply chain operations. Decisions on how products are designed and packaged, along with where products are made, store locations, offsetting, and how much time is allotted for transit all have an impact on GHG emissions and waste within business systems.5 We should all have a strategy for corporate sustainability, its measurement, and how we will report our progress. Shippers will find there are cleaner and more cost-efficient freight practices and integrated systems with good returns on investment. Sustainability is a way to differentiate operations, improve brand loyalty, provide new services, and a road map for long-term goals.

With sights set on achieving more sustainable supply chains by 2020,6 objectives for some companies (e.g., the Consumer Goods Forum, HP, Microsoft, and others) include optimizing shared supply chains, engaging technologically savvy consumers, while also improving consumer health and well-being. The ability to achieve these objectives is essential to the consumer goods industry. It was noted that the difference between success and failure in this industry will be the ability to adapt to rapid and significant change.7 The trends with the biggest influence on industry objectives for the next 10 years include the following:

- Increased urbanization

- Aging population

- Increasing spread of wealth

- Increasing impact of consumer technology adoption

- Increase in consumer service demands

- Increased importance of health and well-being

- Growing consumer concern about sustainability

- Shifting of economic power

- Scarcity of natural resources

- Increase in regulatory pressure

- Rapid adoption of supply chain technology capabilities

- Impact of next-generation information technologies.

Within the context of these trends, industry needs a fundamental change in the way consumer products companies and retailer’s business models integrate for serving consumers. This means working collaboratively with industry, governments, NGOs, and consumers. The four primary objectives coming out of the study are (1) making business more sustainable, (2) optimizing a shared supply chain, (3) engaging with technology-enabled consumers, and (4) serving the health and well-being of consumers. Like the information technology and quality megatrends of the past, sustainability will touch every function, every business line, and every employee.8 Companies that excel in sustainability make shifts in leadership, the systematized use of tools, strategic alignment, integration, reporting, and communication. These firms move from tactical, ad hoc, and siloed approaches to strategic, systematic, and integrated practices.

Add to these trends the following recent events: the signing of the Climate Accord in Paris, release of the UN’s 17 Sustainability Development Goals, toxic air in parts of China causing manufacturing to shut down or slow down, and the Pope’s Laudato Si, and we need to ask ourselves a few questions. One, which new business leaders will emerge in this changing environment? Two, how will these leaders reorganize business as a vehicle for systemic change?

Systems Integration: A Foundation of Competition

There is now a shift in SSCM. Historically, we have seen price-driven yet strategically decoupled SSCM. The move for many is now value driven and strategically coupled SSCM. We see an increasing emphasis on integrated and a more comprehensive set of outcomes, where the integration draws on the following six outcomes: value, resilience, responsiveness, security, sustainability, and innovation. As the language of sustainability has evolved over time, so too will the ways in which we measure performance. Environmental performance has given way to sustainability and innovation is yet another lens we can use to see this evolving paradigm. To take this concept further, others are extending sustainability to understanding and enabling the purpose of corporations as creating “shared value”9 not just profit. So what are we getting at? Sustainability calls for the integration of systems like no other business paradigm.

Why focus on sustainability beyond the firm to the supply chain? Systems integration and the increasing importance of supply chains as the basis of competition call for every business to go beyond its own four walls to better measure, monitor, and manage sustainable supply chains. The reality of managing supply chains is dynamic and requires a concerted effort to align with new programs and opportunities such as sustainability. Ironically, the realities of managing supply chains are the same as sustainability (i.e., visibility, control, risk, transparency, complexity, and collaboration). Strategic sustainable development can help organizations to overcome the obstacles of paradigm change and provide a new path towards the identification of opportunities and planning.

Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development

The Natural Step (TNS: www.naturalstep.org) is an organization founded in Sweden in the late 1980s by the scientist Karl-Henrik Robèrt. Following publication of the Brundtland Report in 1987, Robèrt developed The Natural Step framework,10 proposing four system conditions for the sustainability of human activities on earth. Robèrt’s system conditions are derived from the laws of thermodynamics, promote systems thinking, and set the foundation for how we can approach decision-making.

The first and second laws of thermodynamics set limiting conditions for life on earth. The first law says that energy is conserved; nothing disappears, its form simply changes. The implications of the second law are that matter and energy tend to disperse over time. This is referred to as “entropy.” Merging the two laws and applying them to life on earth, the following becomes apparent:

- All the matter that will ever exist on earth is here now (first law).

- Disorder increases in all closed systems and the Earth is a closed system with respect to matter (second law). However, it is an open system with respect to energy since it receives energy from the sun.

- Sunlight is responsible for almost all increases in net material quality on the planet through photosynthesis and solar heating effects. Chloroplasts in plant cells take energy from sunlight for plant growth. Plants, in turn, provide energy for other forms of life, such as animals. Evaporation of water from the oceans by solar heating produces most of the Earth’s fresh water. This flow of energy from the sun creates structure and order from the disorder. So what does this have to do with business practices?

Taking into account the laws of thermodynamics, in 1989, Robèrt drafted a paper describing the system conditions for sustainability. After soliciting others’ opinions and achieving scientific consensus, his efforts became The Natural Step’s system conditions of sustainability and what is now called the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development (FSSD).11 The organization enabling this framework within cities and organizations is The Natural Step Consultancy.

The Framework’s definition of sustainability includes system conditions that lead to a sustainable society.

In this sustainable society, nature should not be subject to systematically increasing:

- Concentrations of substances extracted from the Earth’s crust

- Concentrations of substances produced as a byproduct of society

- Degradation by physical means.

And in that society, people are not subject to systematic social obstacles12 to the following:

- Health

- Influence

- Competence

- Impartiality

- Meaning making.

Positioned instead as the principles of sustainability, to become a sustainable society, economy, industry, supply chain, business, or individuals, we must:

- Eliminate our contribution to the progressive buildup of substances extracted from the earth’s crust (e.g., heavy metals and fossil fuels);

- Eliminate our contribution to the progressive buildup of chemicals and compounds produced by society (e.g., dioxins, Polychlorinated Biphenyl’s (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), and other toxic substances);

- Eliminate our contribution to the progressive physical degradation and destruction of natural processes (e.g., overharvesting forests, paving over critical wildlife habitat, and contributions to climate change); and

- Eliminate exposing people to social conditions that systematically undermine people’s capacity to avoid injury and illness (e.g., unsafe working conditions, a nonlivable wage).

- Eliminate exposing people to social conditions that systematically hinder them from participating in shaping the social systems they are part of (e.g., suppression of free speech, or neglecting opinions).

- Eliminate exposing people to social conditions that systematically hinder them from learning and developing competencies individually and together (e.g., obstacles to education, or personal development).

- Eliminate exposing people to social conditions that systematically imply partial treatment (e.g., discrimination, or unfair selection to job positions)

- Eliminate exposing people to social conditions that systematically hinder them from creating individual meaning and co-creating common meaning (e.g., suppression of cultural expression, or obstacles to co-creation of purposeful conditions).

A review of your organization’s practices and infractions of these sustainability principles is forms a baseline understanding that leaders and organizations can use to focus resources and efforts to bring about change. A five level framework applied to planning and assessment can help any organization better determine why and how to approach change management initiatives. The five levels are the system, success, strategic, actions, and the use of tools.

At the Systems level, you need to understand the system in which you operate and the natural laws that define the biosphere and societies’ relationship with the biosphere. Success is based on the sustainability principles and outlines the minimum requirements necessary for success. The sustainability principles become the minimum and foundation for your operating manual. Strategic guidelines should guide decision-making processes. Using an ABCD planning process, backcasting from your vision of the future provides guidelines for socially sustainable processes of relating transparency, cooperation, openness, inclusiveness, and involvement.13 Actions come from prioritized steps put into action while following strategic guidelines for success in the systems. Finally, applying the appropriate Tools includes management techniques and monitoring processes to guide implementation of strategic planning.

In order to illustrate the issue of sustainability, the FSSD uses the image of a funnel to demonstrate how decreasing resource availability and increasing consumer demand on those resources will eventually intersect, leading to a breakdown of the system (Figure 2.1). If, however, a company moves toward designing and operationalizing regenerative products, processes and systems, resources and demand can continue forward on a sustainable path.

Figure 2.1 The FSSD funnel and ABCD application14

Source: Used with permission from The Natural Step

How can any firm or project team apply the FSSD? A simplified approach (much like Deming’s Plan, Do Check, Act) instead positions Awareness, Baseline, Create a Vision, and Down to Action to form the acronym ABCD, which describes the four steps of the framework to demonstrate its simplicity and its power.

- Awareness: Work to create awareness of the idea of sustainability among stakeholders. Begin internally among managers, cross-functional teams, and within function champions, include line workers, purchasing, and drivers of trucks. When ready, (meaning when you can demonstrate capabilities and alignment with your value proposition) create awareness externally by releasing information first to your key customer(s) and suppliers and then release this information publicly.

- Baseline: Take a close look at all aspects of operations, from stage-gate product design process, to management decision making and key performance indicators. Audit/benchmark current operations to understand the “as is” state and help determine the “to be” state and performance metrics. Include metrics such as CO2 and GHG emissions, other forms of waste and social performance, transportation system design, supply chain practices, and employee and driver awareness.

- Create a Vision: Take what the baseline produced to see where you want to be in the future. Find opportunities for innovation. Set high goals. Define how you will measure success. From these goals, backcast to current operations and decision-making utilizing systems thinking to see how decisions today will or will not move you closer to the future vision.

- Down to Action: Prioritize goals. Assess projects and initiatives by asking if they take your firm toward or away from its vision. Make the business case for return on investment; is this a good sustainable value added (SVA)? Create a contingency plan to anticipate risk management factors such as regulatory and cost-structure changes.

By following this framework, whole communities such as Whistler British Columbia, Madison Wisconsin, and Santa Monica California have strategically integrated sustainability into their planning. Multinational corporations such as Nike and IKEA (to name a few) have applied it to operations. The application of FSSD lends itself well to integrating supply chains, and applied systems thinking to improve business model alignment of critical customers, capabilities, and value propositions. The result, a collective vision of the future, the use of tools including Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol, Environmental Management Systems, environmental and social metrics, and even integrated, closed-loop systems to turn the vision into a reality.

What follows is a brief case study to highlight how Strategic Sustainable Development can be applied to a firm, the integration opportunities for sustainability and extensions to sustainable SSCM.

Case Study: Applying the FSSD within Aura Light

Aura Light, a sustainable lighting company and Blekinge Institute of Technology (BTH), in Sweden had a long-term consulting partnership which led to Aura Lighting changing its strategic direction. In 2009, Martin Malmos, Aura Light CEO announced plans to make some major changes within the organization, based on BTH’s introduction to the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development and the support of a specialist sustainability consultancy, The Natural Step (TNS).

Aura Light started out as a sustainable company from its inception in 1930 as LUMA. LUMA was founded as a reaction to the Phoebus cartel, comprising of Philipps GE, Osram, and others who were campaigning for the planned obsolescence of lightbulbs. As it evolved, Aura Light’s business model was to provide long-life fluorescent light sources to commercial clients and was looking to become “the most sustainable lighting company.” Initially, Aura Lighting examined moving from fluorescent light solutions to LED solutions. The scarce metals and phosphates used in the LEDs could be recycled, but relying on consumers to recycle the products would not be efficient enough to avoid the sustainability impacts altogether. Aura Lighting decided to make even more extensive changes and shift its business model entirely from selling light products to selling light as a service. This would allow the company to control the materials at the end of use. In parallel, Aura Light would also conduct research on LEDs composed of alternative metals.16

Defining Success

The first step was the development of a shared vision of the future, creating a company with regenerative properties. It was crucial for the new vision to uphold the sustainability principles and avoid:

- The systematic increase of concentrations of substances extracted from the Earth’s crust.

- The systematic increase of concentrations of substances produced by society.

- The systematic physical degradation of nature and natural processes.

The potential for people to be subject to structural obstacles to:

- 4. Health

- 5. Influence

- 6. Competence

- 7. Impartiality

- 8. Meaning-making.17

The Natural Step (TNS) conducted a workshop with the Aura Light project team to set the scope of the assessment and conduct a preliminary baselines assessment. TNS conducted a sustainable Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA) following the first workshop. TNS then facilitated a workshop with Aura Light managers four months later, which enabled the company to co-create its new vision: “Aura Light’s vision is to become the global leading partner for sustainable lighting solutions to professional customers.” The definition of success is further described below in Aura Light’s pillars for success and core values:

Figure 2.2 Aura Light’s Pillars of Success18

Redesigning the System with the ABCD Process19

A – Vision

This stage was discussed above in “defining success.” The vision was agreed as “Aura Light’s vision is to become the global leading partner for sustainable lighting solutions to professional customers.”

This stage was conducted in two steps:

Stage 1: Mapping the current business model using the FSSD-BMC framework and life cycle analysis.

Stage 2: Mapping the current value network and analyzing its sustainability implications. A questionnaire was utilized to analyze the stakeholder relationships.

The outcome for step B was identifying the need to change the revenue stream to move from a product-selling business model to a light-as-a-service business model. In its existing model, Aura Light’s sole revenue stream was product sales. The challenges of moving to a lighting-as-a-service business model included:

- Providing confidence to investors about recovering goods if customers failed to pay fees.

- Moving sales focus of physical products from a one-way flow of materials to reuse/recycling model.

- Management routines and incentives are set up for selling (more of) physical products.

- Addressing the potential skills gap within the design group and sales, whose competencies are adapted to designing and selling physical products.

- Low levels of integration between the Aura Light design group and other functions such as business development, procurement, sales, and auditing.

- The attention and communication around sustainability performance are mainly linked to energy-efficiency and not so much to the other sustainability aspects as informed by the FSSD sustainability principles.

- Varying levels of sustainability competency and awareness in Aura Light’s value network partners.

- Clearly communicating the implications of the top-management’s desired shift toward a more service-oriented business model to all employees, value network partners and customers, who are only used to owning their light installations.

C – Brainstorming to close the gap

A second workshop was conducted to brainstorm actions and prioritize. Participants brainstormed and used a context-mapping tool to list possible solutions by theme. Workshop participants were encouraged to think creatively, with the only limitations being compliance with the FSSD’s eight sustainability principles.

In addition, the participants considered three aspects of the life cycle (raw material, production, logistics and installation, use of end product, end of life) to prototype and prioritize actions:

- What had already been done

- What Aura should stop doing

- What Aura Light should start doing.

During the analysis, capacity building and cross-functional expertise became a key enabler for the implementation of a new business model.

The table below summarizes the themes that emerged during the session and some of the solutions proposed:

Various business models were then developed to incorporate the themes and solutions summarized above.

In the final phase, Aura’s CEO and decision makers selected a business model from the options developed in phase C. The most optimal models were prototyped and the resulting LaaS model is below:

Figure 2.3 Business Canvas Map (BCM) prototype of one of the new business model options for Aura Light20

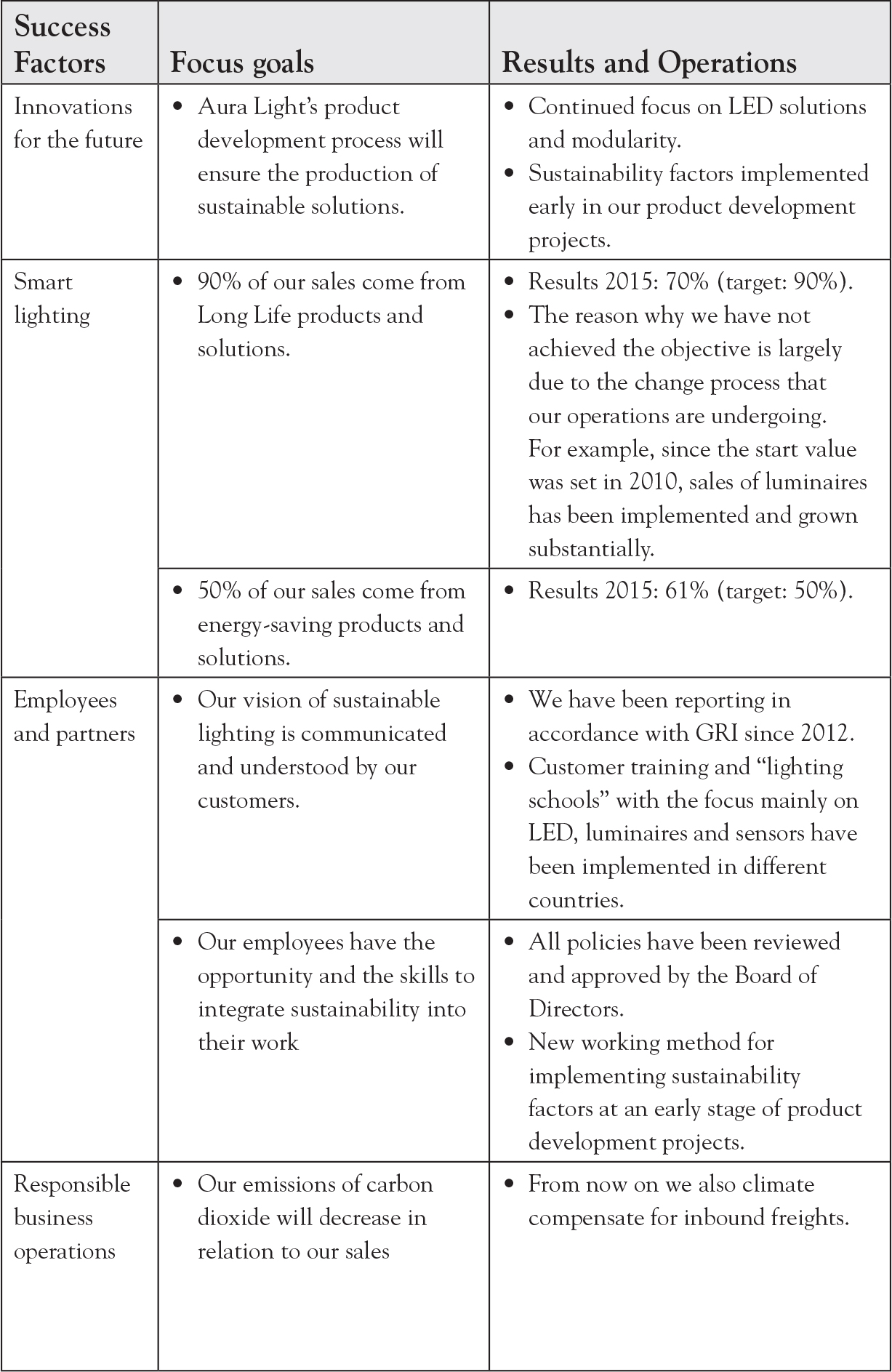

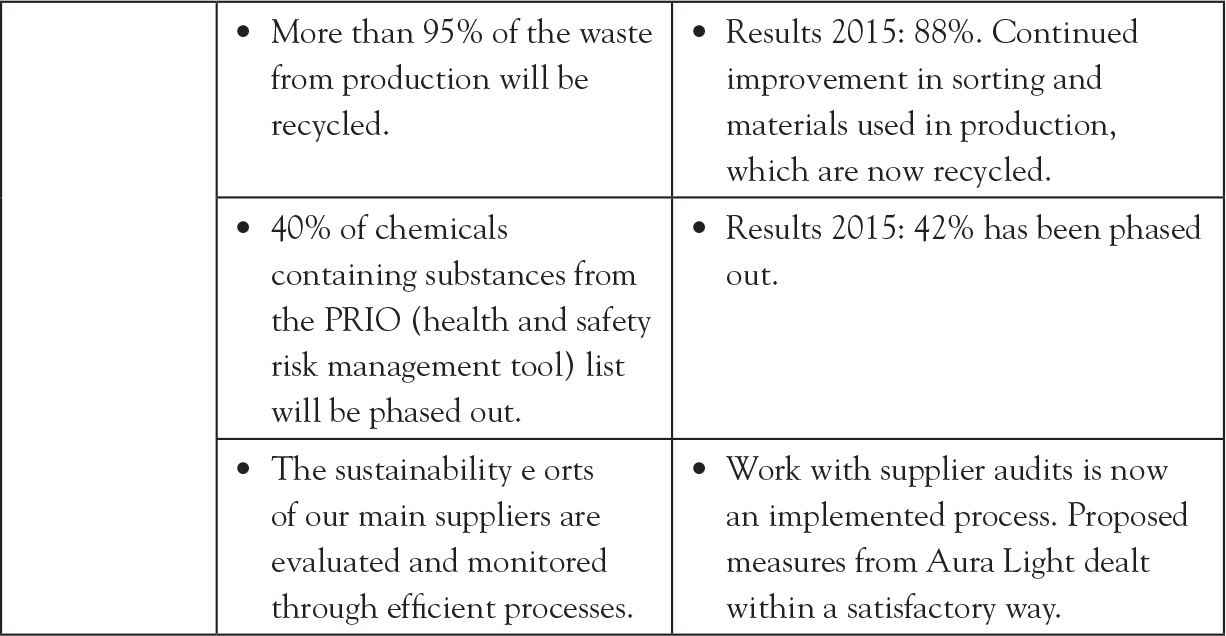

Aura’s Progress4

To date, several actions have been taken, including the establishment of Aura Finance, partnerships with luminaire companies, including the acquisition of Zobra and Noral, and further investments into the sustainability impacts of product development. From the capability development perspective, new employees are required to attend basic sustainability training, with further rollouts to be developed in the future.

The company’s sustainability goals have also been mapped based on the new vision and progress made accordingly, which is reported in the annual report.

Figure 2.4 Aura Light Sustainability Goals21

Information within this chapter has looked at the risk of waiting to change, the trends in sustainability, systems integration opportunity, and a generalizable approach to understanding how your organization can assess, prioritize, and plan for strategically aligned sustainability initiatives. The Aura Light cast study shows how one organization has integrated sustainability internally with the use of the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development and new options to engage their supply chain. Building on Chapter 1, we are attempting to take this complex paradigm of sustainability and breaking it down into constituent parts focusing on systems integration. In doing so, we are not trying to focus on the environmental and social problems of organizations. Instead, we want you to see the Strategic Sustainable Development opportunities for what they are, systems level understanding that goes beyond manufacturing processes, the requirements for defining and measuring success, strategic guidelines, and actions supported by tools that will be expanded upon in the following chapters.

Applied Learning: Action Items (AIs)—Steps You Can Take to Apply the Learning From This Chapter

AI: What sustainability principles are most relevant to your organization?

AI: How would you define success for new initiatives?

AI: What sustainability trends are influencing your industry?

AI: Can you identify integrated systems within your organization or supply chain?

AI: What strategic guidelines for decision-making are already in place and how can sustainability be further integrated into these guidelines?

Further Readings

Broman, G. I., & Robért, K.H. (2017). A Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140; 17–31.

Nidumolu, R., Prahalad, C. K., & Rangaswami, M. R. (2009). Why Sustainability is Now the Key Driver of Innovation. Harvard Business Review, 65–64.

United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, for some context regarding what is happening with regards to environmental AND social opportunities for improving supply chains … https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs

1Procurement Intelligence Unit (2011).

2Accenture (2008).

3KPMG (2011a & b).

4Craft, E., (2012). Envisioning a smarter, healthier supply chain for shippers. Published on GreenBiz.com. Retrieved October 19, 2012 from http://www.greenbiz.com/print/49054

5Craft (2012).

62020 Future Value Chain Project (2011).

7These trends also parallel those recognized by the KPMG International Group in the report, “Expect the unexpected: building business value in a changing world” 2012.

8Lubin and Esty (2010).

9Porter and Kramer (2011).

10Nattrass and Altomare (1999), Chapter 2.

11Broman and Robert (2015).

12These social sustainability dimensions are from the work of Merlina Missimer, Missimer M, Robért K-H, and Broman G. 2014. “Lessons from the field: A first evaluation of working with the elaborated social dimensions of the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development”. Presented at Relating Systems Thinking and Design 3, Oslo, 15–17 October 2014. Published as part of Merlina Missimer’s doctoral dissertation series No. 2015:09, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Department of Strategic Sustainable Development, Karlskrona, Sweden 2015.

13Sroufe, R. (2016). Operationalizing Sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Studies, Issue 1.1.

14The Natural Step: http://www.naturalstep.org/

15Velika Talyarkhan, Graduate Assistant, Duquesne University MBA+Sustainability program.

16Bronman and Robèrt (2017).

17França, Broman, Robèrt, Basile, and Trygg (2017).

18The Natural Step International (2010).

19The following section is summarized from França, César, Broman et al’s paper

20França, Broman, Robèrt, Basile, and Trygg (2017).

21Aura Light’s 2015 Annual and Sustainability Report, http://np.netpublicator.com/netpublication/n97742801