The Internet is a treasure trove of photographic imagery. Artists and designers often combine media elements from this visual archive in inventive ways, or use downloaded images as research for their own creative work. While we admittedly live in a copy/paste culture, using a downloaded image from the web has legal ramifications.

Just because you can download an image doesn’t mean you may use it! A downloaded image may be protected by copyright laws. Copyright is a legal tool for preserving control over the use of a creative work. Books, poems, music recordings and compositions, photographs, paintings, sculptures, radio and television broadcasts, films, and even dances can be copyrighted.

England initiated what we think of as copyright laws in the early 1700s. The widespread use of the printing press and an increase in literacy rates had resulted in printers commonly reprinting texts without crediting their rightful authors, or paying them. Attribution of proprietary rights in intellectual material has had far-reaching legal and economic implications.

Copyright durations vary by nation. In the United States, the length of a copyright used to be the life of an author plus 50 years; on the 50th year after the death of an author, their works would be released into the public domain. When a work is in the public domain, it is not owned or controlled by anyone. Any person can use the material, in any way, without owing anything to the creator. For works created by corporations, the length was 75 years from the date of publication. In 1998, Congress passed the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, which extended copyright by 20 years. This law was authored by a musical-entertainer-turned-Congressman, and was heavily lobbied for by the media industry. The act was nicknamed the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, as Disney lobbied extensively to insure that the law reached back just far enough to protect their copyright over Mickey Mouse. The Act essentially suspended public domain advancement in the United States as covered by fixed term copyright regulations. Copyright law does allow certain types of use of copyrighted material. An image is protected by copyright unless:

The use qualifies as fair use

The image is in the public domain because the author declares it is, or because it is old enough that the copyright has expired

The author licenses it under an alternative model

Fair use is not piracy! Fair use is legitimate and legal use of copyrighted media, as protected by copyright law. Fair use is free speech. Fair use is not file sharing.

Understanding the key principles of fair use is helpful when thousands of protected images are only a mouse-click away.

Reproduceablity is a central trait of digital media. Unlike lithographs, vinyl records, cassette tapes, videotapes, books, or photographic prints, an exact replica of digital media can be made from a digital copy. This is true for digital photograph files, CDs, MP3s, DVDs, and web sites. From sampling to mashups, collage to subvertisements, contemporary artists and content creators use digital files as source material for the derivation of new works. These works are considered new and original, but they are sometimes built with bits and parts of copyrighted works. In the digital age, new works are often created when more than one existing work is recombined in a new way, providing new visual relationships and new ideas.

Tip

For more information about fair use, visit the Stanford Fair Use and Copyright site at http://fairuse.stanford.edu or The Center for Social Media’s paper “Recut, Reframe, Recycle” at http://www.centerforsocialmedia.org/resources/publications/recut_reframe_recycle.

Copyrighted content can be used in a new work if permission is obtained from the copyright holder, or if the media use falls into the category of fair use. Under the fair use clause of copyright law, limited copyrighted material can be used for a transformative purpose, such as commenting upon, criticizing, or parodying the initial material. The four significant factors are:

The purpose of the derivative work

The nature of the derived content: copyright does not limit use of the facts or ideas conveyed by an original work, only the original creative expression

The amount of original work used

The effect that the new work has on the potential or actual market value of the original

Weighing these four factors in a copyright case is not an easy task, which is why judges have been asked to do so. However, successful commercial media that takes advantage of the fair use clause include “Saturday Night Live” skits, “The Simpsons” cartoons, and Weird Al Yankovic songs. These works all make use of parody, one of the traditional protected purposes. (Fig 2.1)

Another traditional protected purpose is educational use in a classroom. Keep in mind that just because you cannot be sued for using appropriated work for assignments, you should be using it for reasons that advance your education, not just for convenience.

Know that the expectations increase for work done outside of a classroom. For commercial media, your transformation of the source material should be significant. We will explore this in Exercise 3.

The fair use clause also does not mean you may plagiarize. Plagiarism, an ethical offense separate from copyright issues, hides the fact that ideas or content have been copied from somewhere else. Even in cases where no legal violation has occurred, plagiarism is a serious ethical violation that undermines the academic endeavor and destroys the plagiarist’s credibility.

Fair use foregrounds that work has been copied and uses the original work as a springboard for further development, often citing the creator in an obvious way so as not to put its source into question.

Appropriation is a word used by media artists to describe the visual or rhetorical action of taking over the meaning of something that is already known, by way of visual reference. For example, Andy Warhol appropriated the Campbell’s soup can visual identity to make large, iconic silkscreen prints. Warhol’s soup cans are an interpretation of the physical object. The visual reference to the original soup can is important, as the viewer needs this information in order to understand the idea that the reference conveys. (Your personal translation of this could range from a feeling associated with something as simple as a popular American icon or comfort food to repulsion at the commodification of domestic life.) By transforming not only the size and graphic palette for portraying the soup cans, but also the place where the viewer will encounter them (an art gallery as opposed to a grocery market), Warhol appropriates the original Campbell’s soup cans to create art that relates to popular culture in its iconic form. Appropriation falls into the category of fair use.

Note

Ironically, we do not have copyright permissions to show Warhol’s paintings or photographs of his Campbell’s soup cans in this book! Try an image search if you’re curious about viewing this work.

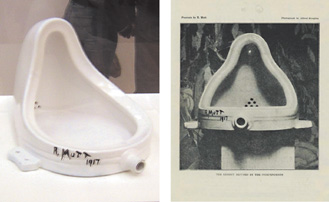

Marcel Duchamp was the first known artist to appropriate a common object in his art. This challenged the art community in its definition of what is or is not labeled art. Duchamp believed that declaring an object a work of art was the artist’s main role in creating art. In the case of Fountain, he took a urinal, turned it on its side, and signed it with his pseudonym, R. Mutt. (Fig 2.2)

In this act of appropriation, the everyday object became something other than what it once was. Duchamp’s transformations included the addition of the signature to the porcelain, the change of context from a bathroom to a gallery, and the change in purpose (the status of the urinal before it fell into Duchamp’s hands is unknown, but after 1917 no one has used the urinal that R. Mutt signed for the purpose of waste containment). In these ways, Duchamp’s use of the urinal foregrounded the viewer’s understanding of the urinal as a concept and an object. This foregrounding is one of the central motifs in appropriation. In addition to fair use, many works are in the public domain or are licensed Creative Commons.

Determining what is protected, what is fair use, and what is free to use is part of the cultural producer’s job. A few search techniques will make it easier to successfully sort through the vast online image archive.

Artists who create new media by way of appropriation often work at the edges of copyright law and fair use. It can be conceptually or politically efficacious to break or side-step societal rules. Authorship and ownership are fluid, abstract concepts. Rule breaking provides visual, political commentary. Furthermore, artists understand that most legal consequences will lead to greater public awareness, positively impacting the work.

In 1979 Sherrie Levine photographed 22 of Walker Evans’s Depression-era photographs as a comment on authorship and reproduction. In 2001 Michael Mandiberg made high-resolution scans of these images, and made them available for download and printing on AfterSherrieLevine.com, complete with certificates of authenticity to be signed by the user. (Fig 2.3) The goal was to comment on the transition from analog reproduction to digital reproduction, and the impossibility of controlling a work in the digital age when each digital file (CD, MP3, DVD, etc) is itself the source for making perfect copies of that same file. The second goal was to create an art object that accrues cultural value by negotiating art history and theory, yet which has little or no economic value. Whereas a certificate of authenticity is conventionally used to preserve the economic value of an art object through a limited edition, here the certificate is used to insure it has none.

Figure 2.3. AfterSherrieLevine.com, Michael Mandiberg, 2001, web site with high-res scans and certificates of authenticity.

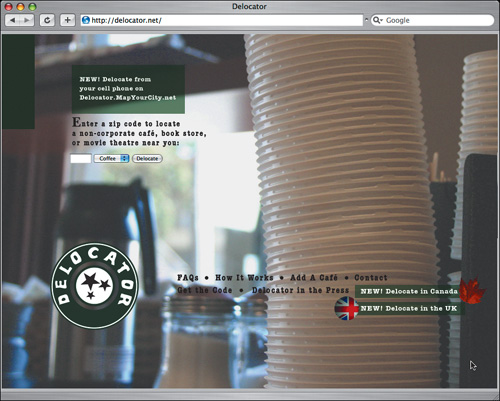

Appropriation can be used to reinterpret language, both visually and verbally. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain is a visual example of this type of reinterpretation, where the urinal becomes art. Delocator.net, xtine’s website for locating and supporting locally owned businesses (launched in 2005) reuses the concept of an online retail store locator to “delocate” away from mainstream, chain stores. (Fig 2.4) The site was originally launched with a database full of Starbucks addresses and an empty set of local cafés on facing sides of a zip code results page. Users from all 50 states contributed to the database so café-goers could find and support neighborhood cafés. In 2006 the site was adjusted to collect locations for independently owned movie theaters and bookstores; other types of businesses will be added as the site grows.

Exercise 01: Advanced searching in Google[*]

Open Google Image Search (http://images.google.com) in a web browser.

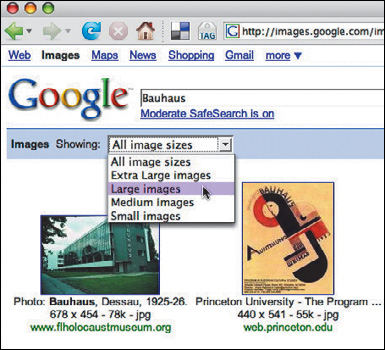

Type the word “Bauhaus” into the search field and click the Search Images button. The search engine will return all images related to the word “Bauhaus.” (Fig 2.5)

Filter your results by file size. Click on the pull-down menu next to the word “Showing:” near the top of the search results page. You can choose from a range of small to extra large images. Select “Large images” from the pull-down menu. (Fig 2.6) The page will reload showing only images larger than 600 by 800 pixels and smaller than 1200 by 1600 pixels. (Pixels are the basic units of image displayed on screen.)

Expect errors! Nearly every search result produces errors. Sometimes errors follow a pattern that can be identified and excluded from the search query. In this case, your results are likely to include images of the 1980s band Bauhaus. Add the word “band” to the search field preceded by a minus sign (“-band”) to remove results for the band.

Results can be limited by searching for a specific phrase. To search by a phrase, enclose the words in quotes. A search for “Bauhaus Dessau” should result in mostly images related to the Bauhaus at Dessau. Dessau, Germany, was the location of the Bauhaus from 1925 to 1932. When you put quotes around your search phrase, Google looks for web pages where that exact phrase appears. Without quotes, Google simply looks for pages where those words both occur, whether they appear together or not. Make sure to reset your image size to “All image sizes” to see the maximum number of search results. (Fig 2.7)

The more specific your keywords are, the better your results will be. If you are looking for images of any of Marcel Breuer’s steel tubular chairs, try “Marcel Breuer steel chair” as your search term. But if you are looking for an image of Marcel Breuer’s famous Wassily armchair, try “Marcel Breuer Wassily chair” as your search term. You could further refine that search by adding any of the following keywords: “original,” “leather,” “canvas,” “brown,” “black.” If you want to find an original Marcel Breuer Wassily chair in black, you can type “Marcel Breuer black original.”

Click on one of the images from your search to bring up the Image Results page.

Click the “See full-size image” link to load the full-resolution image in its own window. (Fig 2.8)

Download the file. You can drag the file to your desktop from the browser, choose File > Save, or right-click the image with the mouse and choose Save Image As. (Fig 2.9) Save the file on your hard drive so that it will be easy to locate. (The desktop or Documents folders are typical storage locations for short working sessions.)

Public domain images have no licensing restrictions. An image automatically enters the public domain when a copyright expires. As media corporations struggle to control their brands by repeatedly extending copyright terms, less content is able to enter the public domain. The irony is that the copyright was introduced to protect authors from corporate power.

Several alternative licensing models exist, the most popular of which is the Creative Commons license. Creative Commons operates under the tagline “Some rights reserved,” and offers a range of licenses with varying degrees of control over whether derivative works and for-profit uses are allowed. (Fig 2.10)

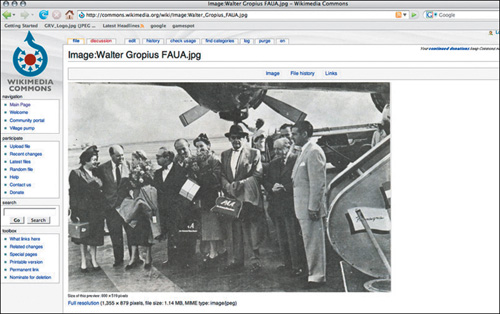

Wikimedia Commons (http://commons.wikimedia.org) and Flickr (http://flickr.com/creativecommons) focus partially or exclusively on public domain or Creative Commons licensed images. Wikimedia Commons is an archive of public domain and Creative Commons images. Much like Wikipedia, it is organized by historical subjects, and is collectively edited and maintained. Flickr is a photo sharing site that encourages the culture of sharing through many of its features, and many Flickr users license their photographs under Creative Commons.

Go to the Wikimedia Commons (http://commons.wikimedia.org) and search for Walter Gropius, the founding director of the Bauhaus. (Fig 2.12)

View several of the images, and notice that the images are either in the public domain or licensed Creative Commons. (Fig 2.13)

Go to Flickr (http://flickr.com), click Search and then click Advanced Search. (Fig 2.14-16)

Type in “Bauhaus,” and choose “Only search within Creative Commons-licensed photos.” Everything in your search will be CC licensed, though not all will allow derivative works (for example, using the image in a collage) or commercial use.

Notice that all of the images in the search are organized by tags. A tag is a word or phrase used to categorize web content. In this case, many images share the tag “Bauhaus.” (Fig 2.17)

Clicking on a tag will reveal the tag’s cluster page. (Fig 2.18)

Upon setting a Creative Commons license (Fig 2.19), the creator of the work decides if both commercial and noncommercial uses are allowed; if others are allowed to modify the work once it is licensed (derivative work); and, if derivative works are allowed, whether or not the newly modified work also has to be licensed with CC (share alike).

The six types of licenses and a very brief description of each follow. More information can be found on CreativeCommons.org. All CC licenses state that the original author will be given credit, in addition to the following details:

Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives (by-nc-nd). This license provides the least freedom to others. The work cannot be used for commercial purposes and derivative works cannot be made. It would be illegal to use this work as part of a collage.

Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike (by-nc-sa). This license allows others to build upon the original work. This work could legally be used in a collage as long as the new work is also licensed in the same manner, with a CC by-nc-sa.

Attribution Non-commercial (by-nc). This license allows others to build upon the original work without having to license it as a CC by-nc. This work could be used, legally, in a collage. However, the resulting work cannot be used for commercial purposes.

Attribution No Derivatives (by-nd). This license allows others to use the work as it is, without making derivative work, for any purpose (commercial or non-commercial).

Attribution Share Alike (by-sa). This license allows others to use the work as it is or in derivative forms, for commercial and noncommercial purposes, as long as the new work is also licensed with the same CC by-sa license.

Attribution (by). This license provides the most freedom to others who want to use the work.

Licensing your own work is easy on the Creative Commons web site. Once the author answers a few simple questions about how the work can be protected or shared, the licensing information is exchanged via e-mail.

This book is licensed CC by-nc-sa.

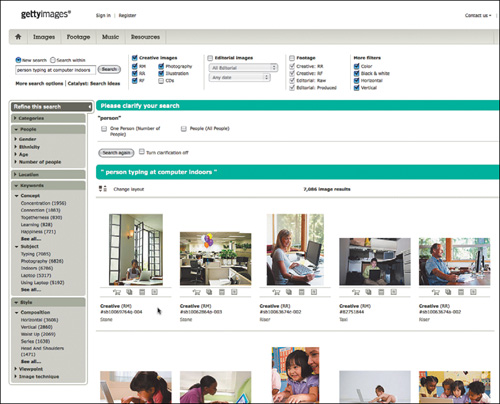

Another source for imagery is stock photography web sites such as GettyImages.com or iStockPhoto.com. These web sites are full of photographs and vector graphics to be used in advertising, corporate media, brochures, reports, and other design applications.

The advantage of these sites is that they seem to have endless search detail.

On the left is an iStockPhoto image from a search for the term “writer” combined with the term “table.” (Fig 2.20) This young woman looks nothing like the two of us as we sat at our computers editing this book on a wiki interface.

The disadvantage is that the photographs have the impersonal feel of an advertisement and often are extremely generic. No one ever looks as happy as a model in an advertisement, and most people feel they are not as physically attractive as the models used in commercial photography. (Fig 2.21) Stock images need to work in a variety of situations to give the buyer flexibility and value. Therefore, it is not surprising to feel a lack of specificity, an overall generic quality, in a stock image.

Stock photographs often look noticeably staged. This inauthenticity is a drawback that requires thoughtfulness on the part of the designer.

Go to Getty Images (http://GettyImages.com) and search in Creative Images for an image of what you are doing right now. In our case, that is “person typing at computer indoors.” You might type “person reading book on couch.” Try adding specifics like your hair color or the types of clothes you are wearing. (Fig 2.22-23)

Refine your search with their search phrases.

Ask yourself if anyone ever looks quite that content, pensive, or photogenic while reading a book unless they are acting for the camera.

One strategy for using stock photography is to radically alter the original image, either through extreme image adjustments in Adobe Photoshop or by tracing the image in Adobe Illustrator. As a transformation to the image, this kind of treatment usually results in using the image under the clause of fair use.

The following illustration was created using a collection of stock photographs as templates for the illustration’s content. Notice how any photographic information has been modified and abstracted in an illustrative form. (Fig 2.24)