Food Security through Public (Food) Distribution System in a Postdisaster Situation: A Comparative Study of Bangladesh and West Bengal (India)

Rabindranath Bhattacharyya

Department of Political Science, University of Burdwan

Jebunnessa

Department of Public Administration, Jahangirnagar University

Introduction

Natural disasters occur only when natural hazards happen in a vulnerable situation. For instance, if any natural hazard like earthquake hits an uninhabited desert area, there will be no loss of life or livelihood. But if such an earthquake hits a highly populated city, it will lead to loss of human lives as well as loss of lives of domestic animals and a huge loss of property and assets. Of course, the degree of such loss would be determined by the capacity of the people living in the area to anticipate such a disaster and to take necessary steps to reduce its impact. If the area is inhabited by a large number of vulnerable people like the aged, children, or disabled who cannot move easily or if the social network remains weak in providing help for emergency evacuation of the people, the impact of such natural hazards will be huge, to be termed as natural disasters. This way, natural disaster is natural hazard combined with vulnerability. Wisner et al. (2004) define vulnerability as “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard (an extreme natural event or process)” (p. 11). Age, income, social network, or neighborhood characteristics all lead to vulnerability to disaster (Flanagan et al. 2011; Tapsell et al. 2010). Normally the policy makers emphasize upon the first part, that is, how to reduce the risk of hazard, because the policy planners have scanty knowledge in specifying those characteristics of a group that make them vulnerable to hazard. This leads to overgeneralization of a concrete disaster or postdisaster situation and to the lack of social capacity building for risk governance. But whatever be the causes of vulnerability, it ultimately leads to the lack of three basic securities/needs: food, shelter, and livelihood.

Thus, this chapter is an attempt to explore to what extent the existence of a stable and operational public distribution network may ensure food security in a postdisaster situation, on the basis of a comparative study between Bangladesh and West Bengal (India) that has been necessitated by homogeneous topographic, ecological, environmental, and cultural traits of Bangladesh and West Bengal. A large province of Bengal was divided by the British in 1905 “into a western part (‘Bengal’) and an eastern part (‘Eastern Bengal and Assam’)” (Schendel 2009, p. 79), which was later united in 1911. In 1947 after achieving independence from the British, Pakistan was separated from India and East Bengal became a province of Pakistan. In 1955 East Bengal was renamed as East Pakistan and in 1971 East Pakistan became independent from Pakistan (Schendel 2009, p. 96) and took the official name People’s Republic of Bangladesh (commonly known as Bangladesh). West Bengal and Bangladesh thus share a common topography, common ecology, common environmental hazards like flood caused either by incessant rains or by tidal surge due to cyclones, and of course a common language and a common cultural and historical heritage. With these similarities in view, a comparative study of food security in postflood situation has been attempted in this chapter that may lead to the building of a replicable model on implementation of programs for food security in a postdisaster situation for developing countries.

The research questions that this chapter attempts to explore are:

- 1.How does the network of Public Distribution System (PDS) in West Bengal (India) and in Bangladesh in distributing food grains operate in a sustainable manner, especially in a postdisaster situation?

- 2.To what extent does the PDS in these two countries ensure food security in a postdisaster situation, especially after the first phase of the crisis is over?

- 3.What else are required for making the PDS more effective in a postdisaster situation?

The chapter is based on secondary data collected from government reports and publications, reports of international organizations, and relevant books and journals. There are two key areas in this chapter for which data were to be collected: (i) the occurrences of flood in West Bengal and Bangladesh and its impact on the people in the postdisaster situation especially in respect of food security, and (ii) the sustainability of the public distribution network in delivering food during the postdisaster situation in those countries. But the limitation of the government record for both the countries is that the data that have been kept in public domain are neither comprehensive regarding the occurrences of floods and their impact in terms of food security nor updated. This is true about the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) of India portal, West Bengal Disaster Management Authority (WBDMA) portal, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India’s portal, as well as the disaster management department’s portal of the Government of Bangladesh. For example, the Disaster Data and Statistics page in the NDMA website presents a table along with a heading “Some major disasters in India” in which a few disasters in some of the 29 states and 7 union territories since the year 1972 up to 2014 have been presented in 30 rows and 4 columns incoherently. The West Bengal Disaster Management & Civil Defence Department (WBDM & CD) portal has presented the sequence of floods since 1978 up to 2013, although why flood occurrences in 2008, 2009, and 2011, when a large number of people were affected, have been left out of this table remains unknown. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2016) has presented data regarding disasters from 2009 to 2014 in a booklet in an analytical way, although there is a dearth of yearwise data distribution. Hence, regarding the record of flood instances and its impact, the author had to compile data from relief reports and assessment reports of nongovernment organizations such as ReliefWeb, Oxfam, and Save the Children, other than government records, although in comparing the data of the two countries in terms of specific year and units of analyses such data provided by the authors remain limited. The Food Security portal facilitated by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) as well as the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank research papers has been used in this chapter as one of the major sources of general information as well as background research reports of food security in both India and Bangladesh, while the official portal of the West Bengal Public Distribution System and the official Food Planning and Monitoring Unit portal of the Ministry of Food have served as the government records regarding the beneficiaries of the public distribution system. The Government of Bangladesh has provided the government records regarding the beneficiaries of the PDS. The unavailability of flood insurance data or compensation data in the government domain in Bangladesh has made the assessment of flood damage in Bangladesh limited in nature.

Key Issues

Flood causes damage of crops, crop lands, and thereby leads to temporary loss of livelihood and income of those who are dependent on agriculture. The situation becomes critical if in such situations people on the one hand lack formal disaster insurance mechanisms and on the other cannot cope with the impact of flood by informal risk-sharing mechanisms, including micro-insurance, because of the magnitude of the damage caused by the disaster. “(I)n the case of Bangladesh, formal insurance mechanisms for catastrophes are very poorly developed, and traditional informal mechanism of risk-sharing is unable to respond when major natural disasters occur” (Ozaki 2016, p. 1). Also, Bangladesh has “limited budgetary resources and limited markets to support the proactive transfer of catastrophe risk” (Ozaki 2016, p. 1). In India, however, there are various insurance coverage schemes viz. the Modified National Agricultural Insurance Schemes (MNAIS), Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), and the Restructured Weather-Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) for the damage or loss of crops due to flood or draught. Data reveal that during 2010–2011 to 2015–2016, the number of farmers covered for Rabi crop in West Bengal under MNAIS was 1,943,351 (323,892 on an average per year). And during 2016, the number of farmers covered for Kharif crop in West Bengal was 308,9434 under PMFBY and 1,700 under RWBCIS (Government of India 2017). Consequently, food security remains the key issue in a postflood situation. Various policy options such as agricultural insurance, micro-insurance, gratuitous cash relief, and PDS are available to address that issue. However, in the context of limited budgetary resources of a country, PDS may act as an effective tool in providing food security in a postdisaster situation.

Government concern for the management of disaster focusing on the capacity building, prompt responses to any threats of disaster, assessment of the impact of disasters, and rehabilitation and reconstruction in the postdisaster situation is a recent phenomenon both in India and in Bangladesh. In a concerted way, government initiatives for disaster management started in India since the passing of the Disaster Management Act 2005. In Bangladesh, such Disaster Management Act was passed in 2012. That may be one of the major reasons for the dearth of comprehensive books, specifically on food security in a postdisaster situation or, more generally, on disaster management in both India and in Bangladesh. Nevertheless, recent attempt to explore disaster risk reduction (Pal and Shaw 2018) is relevant in this context. Two chapters in that book have discussed the risk-reduction issues of West Bengal and Bangladesh. In Chapter 6 (by Maitra), the focal point of the analysis is the role of disaster management department of the Government of West Bengal in view of the shift of focus from crisis management to disaster risk reduction. Statistics of cyclones and floods in West Bengal, as mentioned by the WBDMA, have been presented here along with the statistics of earthquakes and landslides of West Bengal. Thereafter, the mechanisms to mitigate the challenges posed by such disasters have been discussed. Chapter 12 (Pal and Ghosh 2018) has discussed the details of various structural and nonstructural measures adopted for disaster risk reduction in the wake of Aila cyclone in the Sundarbans region in West Bengal.

Disaster Law Emerging Thresholds (2018), edited by Amita Singh, has explored through 24 chapters the appropriate legal frameworks for reducing risks of disasters and institutional reforms toward capacity development for community resilience. Chapter 5 of this book by Ahmad has reviewed the disaster law and community resilience in Bangladesh, concentrating on the risk profile and disaster policy of the country. Chapter 22 (Bhattacharyya) has discussed the limitations in implementing laws in reality in reducing disaster risk, with a case study of Mandarmani sea beach in West Bengal.

The book titled Strategic Disaster Risk Management in Asia, edited by Huong Ha et al. (2015), contains 15 chapters revealing various issues of disaster risk management viz. the role of the polity, the administration, the armed forces, and the community in building capacity for risk reduction, preparedness for responding to disaster, and reconstructing the postdisaster scenario in the context of India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Philippines. In Chapter 2 (Banu), an assessment of the steps and programs in the five-year plans for the reduction of risks and responses to the consequences of disaster in Bangladesh has been attempted. Chapter 9 (Bhattacharyya) has focused on the political and administrative reconstruction process in post-Aila (cyclone) Sundarbans region, with a case study of Bally II Gram Panchayat in Gosaba block.

Chakraborty et al. (2013), on the basis of a micro study of the Debhog Gram Panchayat in Sabang administrative block of Paschim Medinipur district in West Bengal, have analyzed the nature and effects of floods on the people along with the government policies to natural disasters and have attempted to develop a conceptual framework on the basis of vulnerability.

Although the authors could not find any book/report (government or nongovernment) establishing the relationship between PDS and food security of the flood-ravaged victims or so to say of any disaster either in India or in Bangladesh, there are many reports, discussion papers, and individual research papers on PDS in India as well as in Bangladesh. The report by the NITI Aayog Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office, Government of India (2016), has made a comparative study of 2004–2005 and 2011–2012 panel data in showing the coverage, access, and use of Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS), the role of TPDS and Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) in determining the nature of food consumption in view of an increase or a decrease in income, and the efficiency of the PDS. The report, although has not established any link between the impact of disasters and the decrease in income, has recommended for initiating cash transfer as a pilot program in a few districts through PDS because it has found that “cash subsidies instead of in-kind subsidies via the PDS could enhance dietary diversity” (NITI Aayog, Government of India 2016, p. viii). Even if quite dated, in a long World Bank discussion paper on PDS in India (1997), Radhakrishna and Subbarao (1997) discussed the prospect of a reformed and restructured TPDS, which was then newly initiated, in view of three aspects: (i) incidence of fallen poverty in the context of faster serial production than demand; (ii) growth of well-developed and integrated agricultural marketing infrastructure; and (iii) development of Panchayati Raj as decentralized democratic institutions that might take the responsibility of implementing poverty alleviation programs.

In an analytical report on PDS in India, Balani (2013) wrote that in India National Food Security Act (2013) rests on the existing TPDS mechanism to deliver these entitlements. In that report, Balani has shown several gaps in the implementation of TPDS. These include inaccurate identification of households in inclusion or exclusion of targeted beneficiaries and a leaking delivery system. Such lacunae get increased by the fact that the National Food Security Act 2013 does not mention the disaster-hit people within the targeted groups of public distribution. Thus, in case of a postdisaster situation, the gaps in implementation of said Act increase, and leading to relief distribution politics as well.

Habiba et al. (2015) edited the book titled Food Security and Risk Reduction in Bangladesh that contained 15 chapters. The book by drawing the experiences of various national- and community-level programs has discussed the challenges for ensuring food security and their implications for risk reduction in Bangladesh. Chapter 13 (Parvin) has addressed the vital issues of climate change, flood, food security, and human health, with an interconnected dimension in Bangladesh.

In a 227-page-long Bangladesh development series paper (No. 31), the World Bank (2013) has made an assessment of reducing poverty in Bangladesh during 2000–2010. In that series paper, chapters 7 and 8 has elaborately discussed the repercussions of food price shocks on wages, welfare, and policy responses and the role of safety nets to cope with the vulnerabilities. In Chapter 8, there is a section on the public food distribution system in Bangladesh, which was established in the wake of the Bengal famine of 1943. The objectives of the public food distribution system (PFDS) as mentioned there are basically three maintenances, namely,(i) security stock in case of emergencies and weather-related shocks, (ii) stability of food prices, and (iii) food security for the poor population (World Bank 2013). The paper also revealed the data regarding an increase in food grain stock and distribution. “The 2010-11 target for public distribution increased to 2.29 million tons, and in 2011-12, it was 2.1 million tons. Currently, public stocks total 2.77 million” (World Bank 2013, p. 104). Although there was an increase in the stock of food, the paper indicated the deterioration of the quality of PFDS food grain and leakage of food distribution, the impact of which is borne by the safety net beneficiaries.

In the chapter on PFDS in Bangladesh, Ali et al. (2008) compared the food policy of India with that of Bangladesh and the benefits that Bangladesh got in procuring rice in the post-1998 flood situation. The three underlying objectives of PFDS in Bangladesh, as they viewed, are (i) implementation of ceiling prices,(ii) poverty alleviation and food security for all vulnerable groups, and (iii) disaster management.

One major Bangladesh–India initiative was taken by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) titled Situation Analysis on Floods and Flood Management, where Prasad and Mukherjee (2014) underlined five broad thematic areas, and the first among these areas is “food security, water productivity and poverty” (p. 3). The IUCN concentrated on creating “situation analyses” on each thematic area and related issues. The analysis that the IUCN has taken is thorough and deep probing in identifying core issues and their significance within the India–Bangladesh geographic focus. But the analysis has not focused on the PDS system of both the countries for ensuring food security during postflood situation.

On the basis of the above review of literature, it may be said that there is a dearth of literature linking the operations of PDS in a postdisaster situation as a mechanism to respond to the impact of disaster whether in India or in Bangladesh. Nevertheless, the literature on PDS is based on the good governance discourse that focuses on the role of government in delivering service for and ensuring accountability to the citizens for sustainable food security. In a postdisaster situation, the government faces the vulnerabilities of the population in a much broader way, and hence the government should have the capacity to plan and prepare for response, to coordinate assistance, and to develop policies on food security.

Flood and Food Security

For the healthy well-being of a people, nutritious food is required. That is not possible without a certain level of income and accessibility of the food in the area. Disasters always have a direct impact on the various livelihoods that put the income of the disaster-hit people in jeopardy. This is more so in rural society in developing countries (FAO 2015). Food security and livelihood in India and Bangladesh, both being developing countries, get affected in case of disaster. Going by topography, Bangladesh and West Bengal, a constituent state in the eastern part of India, are akin to each other. Consequently, the nature of disasters that hit West Bengal is of similar nature to the disasters that hit Bangladesh. Cyclones often have a trailing route to both West Bengal and Bangladesh, originating from the Bay of Bengal, creating tidal surge, and thereby resulting in flood. Likewise, because of heavy rains, floods are also common in West Bengal and Bangladesh. Incidentally, both these areas depend heavily on agriculture for livelihood.

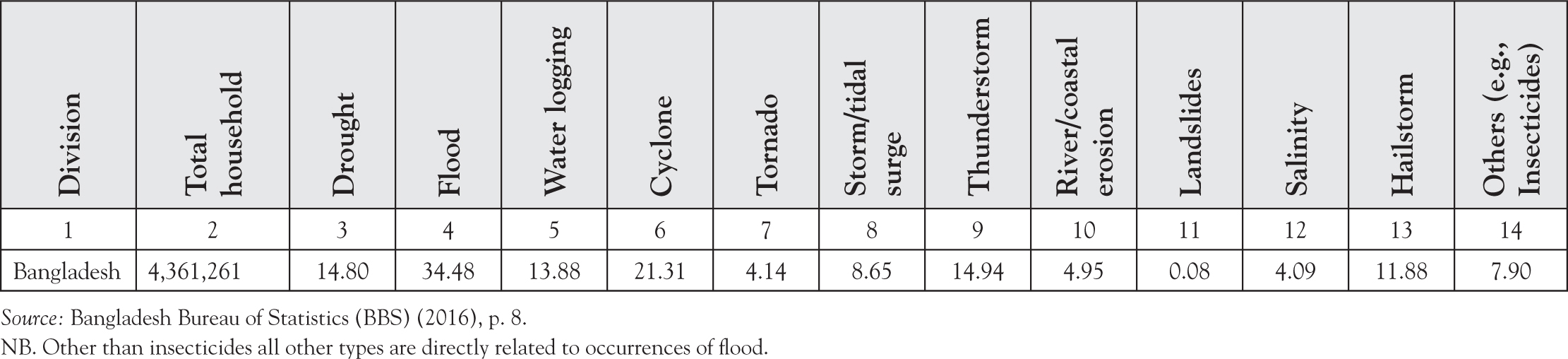

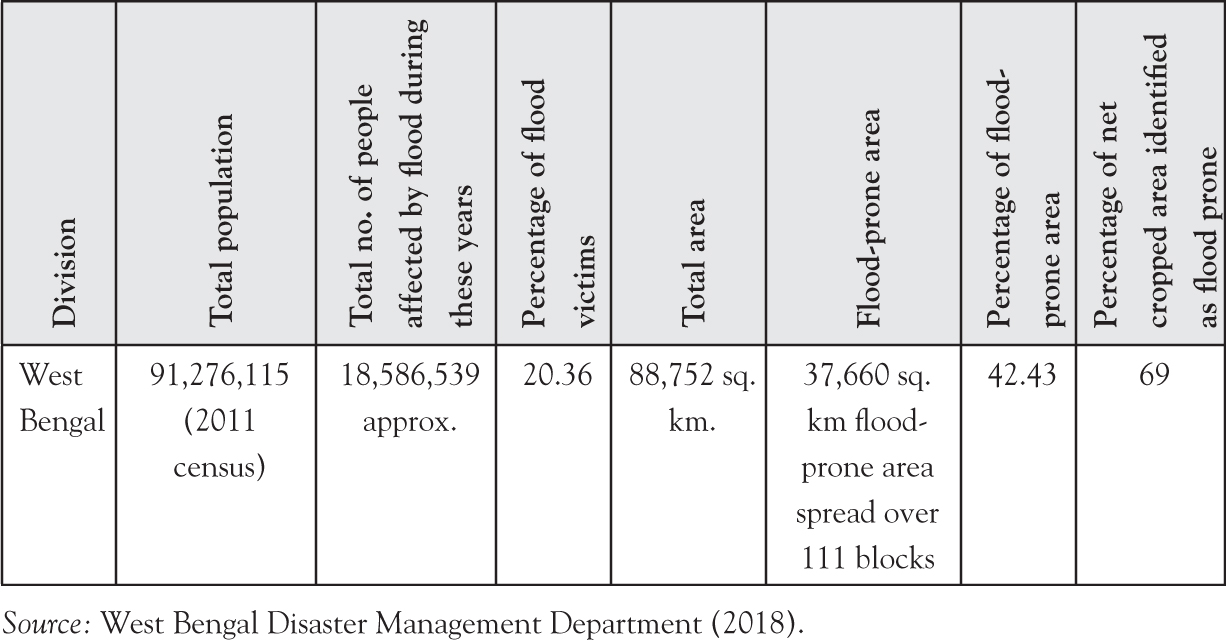

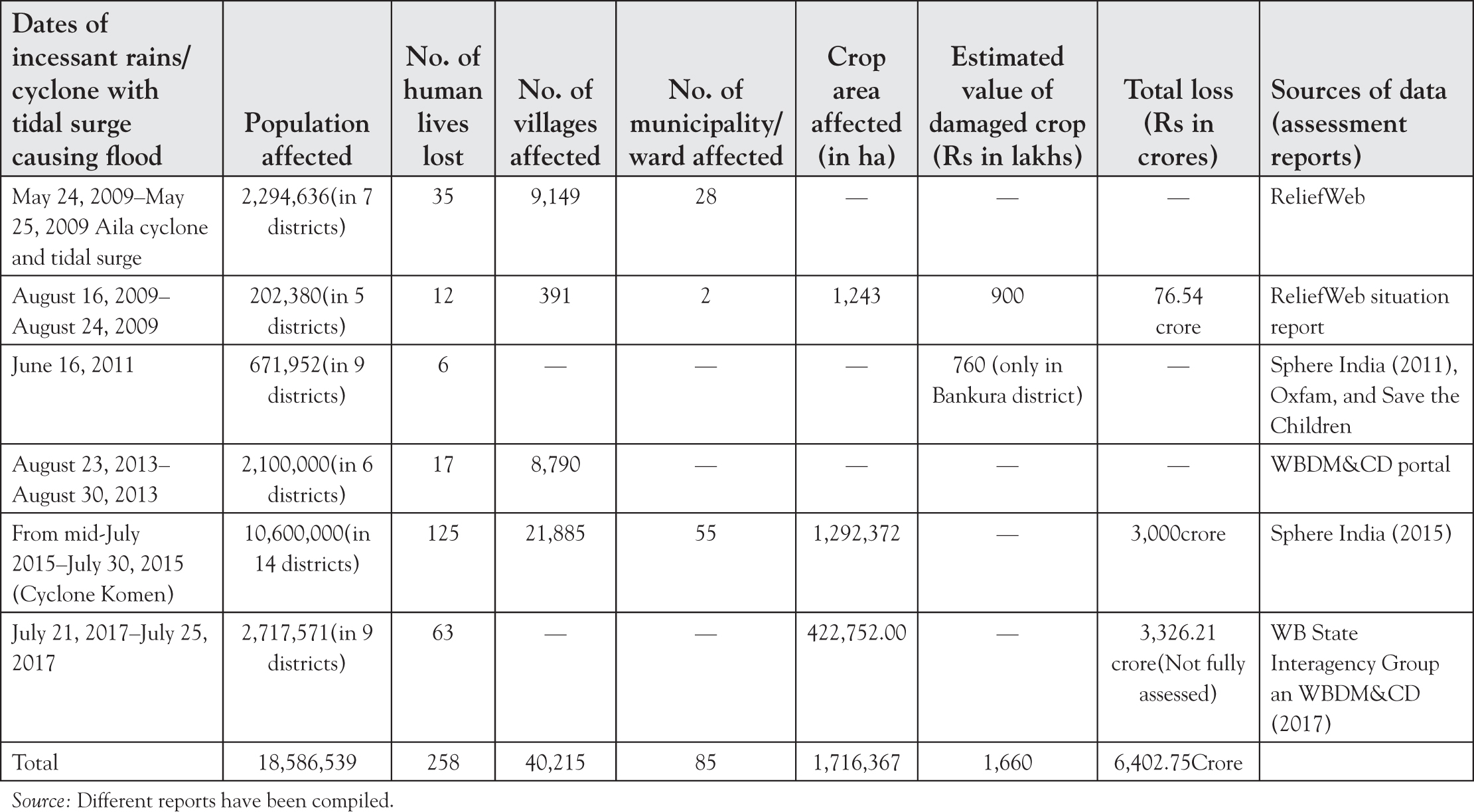

Agriculture and allied sectors are the largest employers in both West Bengal and Bangladesh. In West Bengal, about 39 percent of the total workforce and about 70 percent of the total population depend on agriculture for their livelihood. Also agriculture contributes to 20.34 percent of the net state domestic product (Bengal Chamber of Commerce 2013). On the other hand, “Agriculture provides livelihoods for over 60% of the population of Bangladesh. However, people living in the flash flood and drought prone districts in the northwest and the saline affected tidal surge areas in the south struggle year after year to produce enough to eat or earn a living” (World Bank 2013, p.38). Since in both the countries flood occurs almost regularly, a huge number of people, as found in Tables 7.1 to 7.4, become affected at different levels with regard to their livelihood and income. In postdisaster situations, the affected people face the basic problem of food security because of the temporary loss of work and the basic problem of the administration remains to distribute food grains in a sustainable manner especially after the first phase of crisis is over. Although there has been no study linking the postdisaster impact on the livelihood and income of the flood-affected people in West Bengal or in Bangladesh, on the one hand, and their food security status, on the other, it may be deduced that the impact on the flood-affected people’s livelihood and income is bound to put impact on food security. IFPRI (2009) in their study on Indian State Hunger Index (ISHI) placed West Bengal in the 8th place among 17 states in India, with the ISHI score of 20.97 (comparable Global Hunger Index [GHI] Rank 60, although India got Rank 66 with a score of 23.7), which was “alarming.” Bangladesh was compared with West Bengal in that report as having 25.2 score (with GHI Rank 70). After 2009, there was no other study on ISHI either by IFPRI or by any other organization. But the GHI 2017 shows Bangladesh with the rank of 88 (GHI score 26.5) and India with the rank of 100 (GHI score 31.4) (IFPRI 2017, p.13). This means the food security status of both the countries has deteriorated.

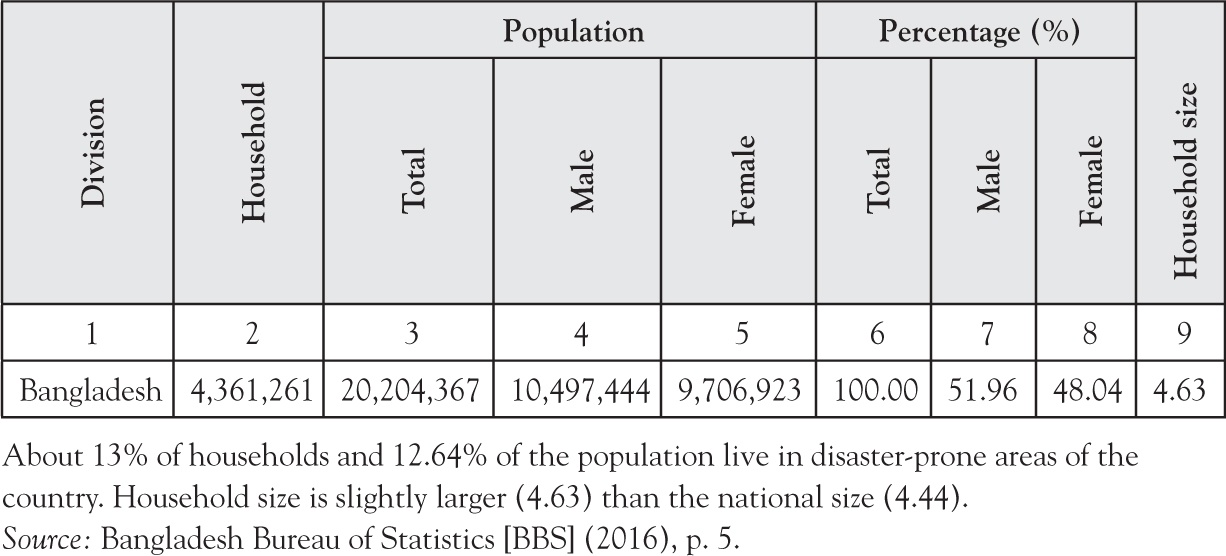

Table 7.1 Household, population, and household size in disaster-prone areas in Bangladesh

Table 7.2 The distribution of disaster-affected households by division and disasters, 2009–2014

Table 7.3 The percentage of flood-prone areas and flood-affected victims in West Bengal, 2009–2017

Table 7.4 Yearwise distribution of disaster-affected population in West Bengal and the available assessment of damages 2009–2017

According to Bangladesh Disaster Census report during 2009–2014, the average nonworking days per household due to flood was 17.63, and the total percentage of nonworking days due to flood was 26.93 (BBS 2016, p. 9). During that period, the amount of total losses and damages has been calculated at 42,807.19 million taka, and that is 23.23 percent of the total losses and damages incurred by other natural disasters (BBS 2016, p. 10). The report has also mentioned that, during the Financial Years 2009–2015, the average annual GDP volume is 11,378,286 million BDT (BBS 2016, p. 19). In case of absence of such damages and losses at the household levels, the report says the GDP volume would be up by an average of 0.30 percent per year.

As far as food security in the postdisaster Bangladesh is concerned, mostly the poor and victims of natural disasters become the beneficiaries of the distribution of food grains under the PFDS. In Bangladesh, the Humanitarian Assistance Programme Implementation Guidelines 2012–2013 are in force for postdisaster crisis management and relief distribution. “An estimated 2.8 million tons of grain were distributed in 2012-13 (1.7 million tons of rice and 1.05 million tons of wheat) under monetized and non-monetized social safety net programs (SSNP)” (Ministry of Food, Government of Bangladesh 2015, p. 2). Nevertheless, according to the IFPRI, Bangladesh’s high-poverty and undernutrition rates are exacerbated by frequent natural disasters and a high population density, and more than 17 percent of the total population (160 million) are still extremely poor (IFPRI 2018).

However, the assessment of the IFPRI (2016) regarding the flood impact reveals different views. On the basis of evaluation of “both household coping mechanisms and recovery rates in addition to examining how effectively national food distribution programs targeted food aid to those in greatest need” (IFPRI 2016, p. 11), the IFPRI (2016) came to the conclusion that in Bangladesh (i) poorest people cope with the floods by taking loans from private bank; (ii) although 53 policy advisory memos were produced by the Food Planning and Monitoring Unit of the Ministry of Food and Disaster Management between 1998 and 2001, these memos “needed to respond to the impacts of the flooding”; and (iii) import of huge quantity of rice in the private sector stabilized food market and prevented famine (p. 12). The highlights reveal that PFDS does not work effectively in postdisaster situation in Bangladesh, although Bangladesh has designed and approved the National Food Policy (2006) and the National Food Policy Plan of Action (2008–2015). It should be mentioned in this context that nowadays, in Bangladesh, the government gives more emphasis on the Vulnerable Group Development Programme in place of the Vulnerable Group Feeding Programme.

In India, the PDS has been operative since 1939, when war time rationing was introduced in Bombay and consequently to other cities in India. Since the 1970s especially since the Garibi Hatao program launched by former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1971 as antipoverty measures, the PDS through fair price ration shops became widely entrenched. But criticisms were leveled against the PDS because of its failure to serve the below-poverty-line (BPL) population, its urban bias, lack of transparency in delivering services, and poor coverage in the states with the highest rural population (Planning Commission, Government of India 2002, p. 368). So, for streamlining the system, the government issued special cards to BPL families and began selling food grains under the PDS to them at specially subsidized prices with effect from June 1997. Thus, the TPDS was initiated for making provision only for the BPL population for whom the allotment of food grains also increased at 50 percent of economic cost from 1 April 2000 (Planning Commission, Government of India 2002, p. 368). Later the National Food Security Act (NFSA) was passed in India in 2013, which ensures “access to adequate quantity of quality food at affordable prices to people to live a life with dignity.” Thus, the NFSA wants to protect all children, women, and men in India including the vulnerable section of population from hunger and food deprivation. The act has detailed the TPDS as “the system for distribution of essential commodities to the ration card holders through fair price shops” and has made enough provisions for reform to deliver the food grains at the doorsteps of the priority people, to give preference to public institutions or public bodies such as panchayats, self-help groups, cooperatives, licensing of fair price shops, management of fair price shops by women or their collectives, and support to instituting grain banks. Yet, the method of identification of the priority people under the TPDS has been left to the state governments; in West Bengal, that is determined by the criteria of remaining below the poverty line.

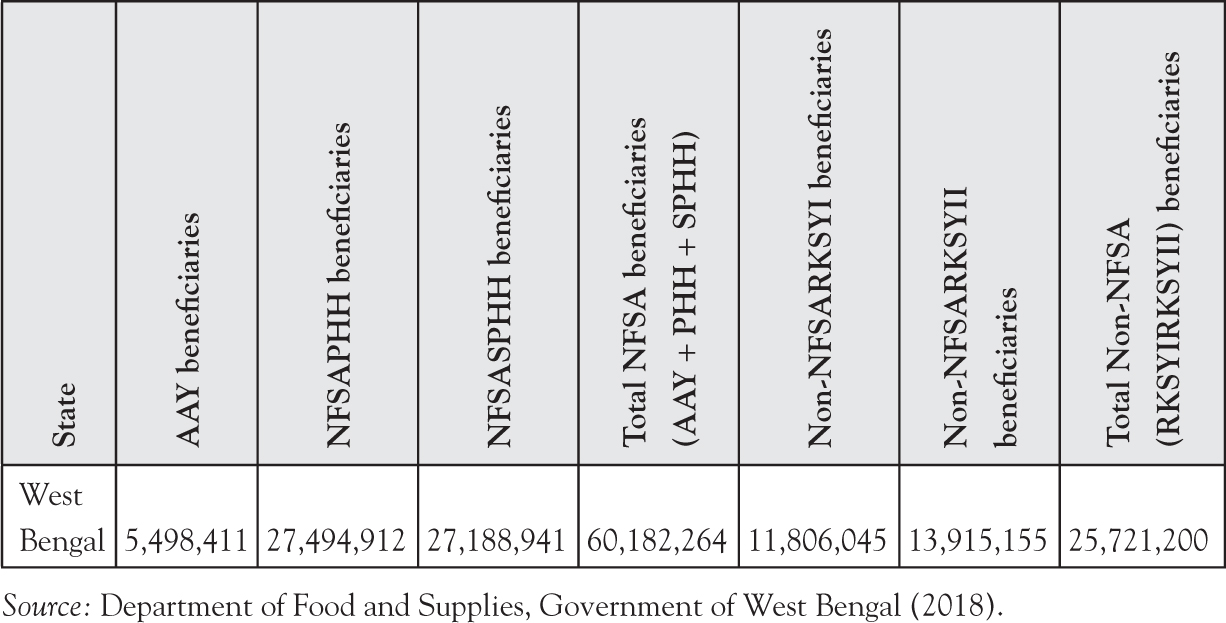

The objectives of the PDS in West Bengal are to focus on providing food security to the people, particularly, the poor and vulnerable sections of the society. For maintaining the effective distribution of commodities, the PDS in West Bengal has been divided into two areas: (i) Urban Public Distribution System for municipalities and municipal corporations; and (ii) the PDS for other areas. The NFSA 2013 has been implemented in West Bengal since February 2016, and since then the beneficiaries have been classified as AAY households, priority household (PHH), and priority household with sugar (SPHH). Moreover, from February 1, 2016, the Rajya Khadya Suraksha Yojana (RKSY or State Food Security Programme) I and II have been initiated to cover all other people (RKSY II is for above-poverty-line [APL] people). Besides, Annapurna beneficiaries (from BPL people) holding special ration cards get 10 kg of rice per month free of cost.

From Table 7.5, it is clear that out of the total population of 91,276,115 in West Bengal, 85,903,464 are covered by the PDS, which is 94.11 percent of the total population. However, among this population, Non-NFSA RKSY II beneficiaries are from the APL population, which is 15.25 percent of the total population. The World Bank (2017) has mentioned the poverty level in West Bengal is 20 percent of the total population on the basis of 2012 BPL estimation, which is close to the national average of 19 percent. On this basis, one may come to the conclusion that food security implementation through the PDS is quite high in West Bengal.

Table 7.5 Beneficiaries of PDS in West Bengal (July 3, 2018)

Despite this positive picture, there are certain gray areas. The National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), on the request of the Department of Food and Public Distribution of the Government of India, conducted a survey of the TPDS in six states in 2015. Three states—Bihar, Chhattisgarh, and Karnataka—implemented the NFSA, whereas West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Assam did not implement NFSA at that time and were following the earlier TPDS. The NCAER attempted to assess whether the past weaknesses of the TPDS were adequately addressed by the six state governments or not. Report specified that although the network of PDS is strong in West Bengal, the average monthly take-home of food grain from PDS per BPL/PHH cardholder household per month in Bihar (4.49 kg) and West Bengal (5.96 kg) is substantially less than that in Assam (29.23 kg), Chhattisgarh (33.81 kg), Karnataka (27.11 kg), and Uttar Pradesh (32.6 kg).

Findings

From the above discussion, it is revealed that in both Bangladesh and West Bengal the PDS has evolved from food grain distribution through fair price ration shops to targeted distribution of food grains for vulnerable sections of the population. In West Bengal, there are BPL cards; likewise in Bangladesh, Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) cards are available for the extremely poor and flood-affected people. According to the International Labor Organization Social Security Portal regarding Bangladesh (accessed June 25, 2018), from January 1, 2010 through December 31, 2010, an amount of 10,972 million taka was spent for VGF. Such scheme corresponds to AAY in West Bengal. Besides, in Bangladesh, there are two other programs under the PFDS: (i) test relief program, which ensures food for work or cash for work, and (ii) gratuitous relief for disaster-affected people. Cash-for-work program in postflood situations also leads to significant gains in the nutritional status of both children aged less than 5 years and women (Mascie-Taylor et al. 2010). In West Bengal, other than AAY, other PDS schemes are NFSA PHH, NFSA SPHH, Non-NFSA RKSYI, and Non-NFSA RKSYII, which provide coverage of more than 90 percent of the total population (Table 7.5). Besides, a huge number of farmers are covered by insurance schemes in West Bengal against the loss of crop due to flood or drought. In India, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 ensures “livelihood security of the households in rural areas of the country by providing at least one hundred days of guaranteed wage employment in every financial year to every household.” Thus, on the one hand, a strong PDS network and the insurance coverage of the loss of crop due to flood have made food security for the vulnerable population in West Bengal a reality. On the other hand, the insurance coverage is poor in Bangladesh. So the dependence of the poor solely on the PFDS in times of flood is quite natural.

In Bangladesh as well as in India, government data show that the PDS is well established with providing food security to substantial population. Nevertheless, the IFPRI revealed that flood-affected people in Bangladesh take private loans more to cope with flood than rely on the PFDS and also the policy memos for the PDS although are adopted, and are not implemented in a postflood situation. In case of West Bengal, the NCAER data also reveals that although the number of beneficiaries is very high in West Bengal, their take-home-per-household-per-month food grain quantity is very low. So, in both the countries there is a discrepancy regarding the PDS between government record and nongovernment assessment.

The leakage is a major issue in any of the PDS. But NCAER report (p. xvii) shows that in West Bengal leakage percentage was as high as 28.19 percent in 2015. Thus, the PDS in West Bengal suffers from large leakages, and the food grains targeted for the BPL people often go to the open market during transportation to and from fair price ration shops. This is very important because India has the largest network of the PDS. In postdisaster situations, such leakage tends to be higher and may lead to politics of relief.

Conclusion

This chapter started with three research questions with regard to West Bengal and Bangladesh about (i) the existence of a sustainable PDS network in a postflood situation, (ii) the effectiveness of such PDS in ensuring food security in postflood situation, and (iii) any more requirements to make PDS more effective. The above exploration leads to the conclusion that both in Bangladesh and in West Bengal, PDS network is quite large and well established. However, there is some lacuna of these networks (mentioned earlier), which should be rectified. Because there is a dearth of analytical disaster census data relating food security status in postflood situation, it is difficult to specify the extent to which the PDS in these two countries may ensure food security in a postflood situation, especially after the first phase of the crisis is over. Yet, in both countries, emergency distribution of food grains following natural calamities for the vulnerable sections has been underscored.

To make the PDS more effective, first, comprehensive data regarding food security containing details about loss of workdays, damage to crops and crop area, impact on livelihood, insurance, relief and compensation amount, immigration after disaster in the postflood situation is required. Second, as in the case of maternity benefits, the National Food Security Act 2013 in India should have a provision on the benefits for disaster-affected people. In Bangladesh, PFDS guidelines mention the provision for disaster-hit people. Finally, to cope with the leakage, private operators in the PDS should not be engaged. In West Bengal, cooperatives, panchayats, or self-help groups may be entrusted with the responsibility of handling the PDS, for which provision has already been made in the National Food Security Act 2013. Sincere attempt to initiate these reforms may ensure the four pillars of food security—availability, access, utilization, and stability—in a transparent and efficient manner in both Bangladesh and West Bengal in a postflood situation.

Ahmad, Md. A. 2018. “Disaster Law and Community Resilience in Bangladesh.” In Disaster Law Emerging Thresholds, ed. A. Singh. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 80–95.

Ali, A.M.M.S., I. Jahan, A.R. Ahmed, and S. Rashid. 2008. “Public Food Distribution System in Bangladesh: Successful Reforms and Remaining Challenges.” In From Parastatals to Private Trade: Lessons from Asian Agriculture, eds. S. Rashid, A. Gulati, and R. Cummings, Jr. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University, p. 115 (pp. 103–34).

Banu, N. 2015. “Chap. 2, Disaster Management in the Five Year Plans of Bangladesh: An Assessment.” In Strategic Disaster Risk Management in Asia, eds. H. Ha, R.L.S. Fernando, and A. Mahmood. New Delhi: Springer, pp. 15–28.

BBS [Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics], 26.06.2016. ‘Bangladesh Disaster-related Statistics, 2015 – Climate Change and Natural Disaster Perspectives’ (presented by Md. R. Islam, Programme Director, Impact of Climate Change on Human Life): http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/National%20Account%20Wing/Disaster_Climate/Presentation_Realease_Climate15.pdf (accessed 10.3.2018).

Bhattacharyya, R. 2015. “Chap. 9, Administrative Planning and Political Response to a Post-Disaster Reconstruction: A Study of Aila (Cyclone)-Devastated Gosaba Block in West Bengal (India).” In Strategic Disaster Risk Management in Asia, eds. H. Ha, R.L.S. Fernando, and A. Mahmood. New Delhi: Springer, pp. 115–28.

Bhattacharyya, R. 2018. “Can Laws Ensure Disaster Risk Reduction? A Study of Mandarmani Sea Beach in West Bengal.” In Disaster Law Emerging Thresholds, ed. A. Singh. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 345–58.

Chakraborty, D., S. Bandyopadhyay, I. Dasgupta, S. Sen, and D. Mitra. 2013. “Chap. 9, Natural Disaster Mitigation in West Bengal.” In The Economic Impacts of Natural Disasters, eds. D. Guha-Sapir, and I. Santos. New York, NY: Oxford, pp. 199–225.

Flanagan, B.E., E.W. Gregory, E.J. Hallisey, J.L. Heitgerd, and B. Lewis. 2011. “A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 8, no. 1, Article 3.

Maitra, H, 2018. “Disaster Governance in West Bengal, India.” In Disaster Risk Governance in India and Cross Cutting Issues, eds. I. Pal, and R. Shaw. Singapore: Springer, pp. 105–26.

Ozaki, M. 2016. “Disaster Risk Financing in Bangladesh.” ADB South Asia Working Paper Series, No. 46, Manila: ADB.

Pal, I., and T. Ghosh. 2018. “Risk Governance Measures and Actions in Sundarbans Delta (India): A Holistic Analysis of Post-disaster Situations of Cyclone Aila.” In Disaster Risk Governance in India and Cross Cutting Issues, eds. I. Pal, and R. Shaw. Singapore: Springer, pp. 225–42.

Parvin, G.A., K. Fujita, A. Matsuyama, R. Shaw, and M. Sakamoto. 2015. “Chapter 13, Climate Change, Flood, Food Security and Human Health: Cross-Cutting Issues in Bangladesh.” In Food Security and Risk Reduction in Bangladesh, eds. U. Habiba, Md. A. Abedin, A.W.R. Hassan, and R. Shaw. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 235–54.

Planning Commission, Government of India. 2002. “Chapters 3 and 4, Public Distribution System.” Tenth Five Year Plan—2002–2007 Sectoral Policies and Programmes, Vol. 2. New Delhi: Planning Commission, Government of India, pp. 365–79.

Radhakrishna, R., and K. Subbarao. 1997. India’s Public Distribution System A National and International Perspective. World Bank Discussion Paper No. 380, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Schendel, W.V. 2009. A History of Bangladesh. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wisner, B., P. Blaikie, T. Cannon, and I. Davis. 2004. At Risk, Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters. London, UK: Routledge.

World Bank. 2013. Bangladesh Poverty Assessment—Assessing a Decade of Progress in Reducing Poverty 2000–2010. Chapters 7 and 8, Bangladesh Development Series, Paper No. 31. Dhaka: World Bank, pp. 94–120.

Internet Sources

Asian Development Bank. 2016. “Disaster Risk Financing in Bangladesh.” Manila: ADB. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/198561/sawp-046.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

Balani, S. December, 2013. “Functioning of the Public Distribution System An Analytical Report.” PRS Legislative Research, p. 2. http://www.prsindia.org/administrator/uploads/general/1388728622~~TPDS%20Thematic%20Note.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2018.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. June, 2016. “Bangladesh Disaster-related Statistics, 2015—Climate Change and Natural Disaster Perspectives” (presented by Md. R. Islam, Programme Director, Impact of Climate Change on Human Life): http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/National%20Account%20Wing/Disaster_Climate/Presentation_Realease_Climate15.pdf (accessed March 10, 2018).

Bengal Chamber of Commerce. 2013. “Government of West Bengal Executive Summary of State Economic Review.” http://www.bengalchamber.com/economic-indicators.html (accessed March 15, 2018).

Department of Food and Supplies, Government of West Bengal. 2018. https://202.61.117.98/RCCount_District.aspx (accessed June 20, 2018).

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2015. The Impact of Natural Hazards and Disasters on Agriculture and Food Security and Nutrition: A Call for Action to Build Resilient Livelihoods, p. 3. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4434e.pdf (accessed May 16, 2018).

Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. 2017. “Compensation for Damaged Crops under Insurance Scheme.” Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 2026. Annexure – I http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Compensation%20for%20Damaged%20Crops%20under%20Insurance%20Scheme.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

IFPRI, P. Menon, A. Deolalikar, and A. Bhaskar. 2009. “India State Hunger Index Comparisons of Hunger Across States.” http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/13891 (accessed May 31, 2018).

International Food Policy Research Institute. 2016. “Highlights of Recent IFPRI Research and Partnerships in Bangladesh: Reducing Poverty and Hunger through Food Policy Research.” https://www.ifpri.org/publication/highlights-recent-ifpri-research-and-partnerships-bangladesh (accessed May 16, 2018).

International Food Policy Research Institute. 2017. Global Hunger Index: The Inequalities of Hunger, Washington DC: IFPRI, p. 13. http://www.globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2017.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

International Food Policy Research Institute. 2018. Food Security Portal. “Country Resources: Bangladesh.” http://www.foodsecurityportal.org/bangladesh/resources (accessed May 25, 2018).

International Labour Organization, Social Security Department, Bangladesh. http://www.ilo.org/dyn/ilossi/ssimain.updSchemeExpenditure?p_lang=en&p_geoaid=50&p_scheme_id=1356&p_social_id=2314 (accessed June 25, 2018).

Mascie-Taylor, C.G.N., M.K. Marks, R. Goto, and R. Islam. 2010. “Impact of a Cash-for-work Programme on Food Consumption and Nutrition among Women and Children Facing Food Insecurity in Rural Bangladesh.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88, 854–60. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/11/10-080994/en (accessed June 25, 2018).

Ministry of Food, Government of Bangladesh. http://www.dgfood.gov.bd (accessed May, 2018).

Ministry of Food, Government of Bangladesh. 2015. “Terms of Reference for Integrated Food Policy Research Program” under Modern Food Storage Facilities Project. http://dgfood.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dgfood.portal.gov.bd/page/cb9f6c96_eeef_486e_adb9_c7b3e786f761/Final%20TOR%20for%20Integrated%20Research%20Program-08-06-01-15.pdf (accessed May 20, 2018).

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. http://www.mospi.gov.in (accessed May, 2018).

National Disaster Management Authority of India. https://ndma.gov.in/en (accessed May, 2018).

National Food Policy 2006, 14 August, 2006. Ministry of Food and Disaster Management, Dhaka, Government of Bangladesh https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/files/BGD%202006%20National%20food%20policy.pdf (accessed May 18 2018)

‘National Food Policy Plan of Action (2008-2015)’ 5 August, 2008. Food Planning and Monitoring Unit (FPMU), Ministry of Food and Disaster Management, Dhaka, Government of Bangladesh. https://www.gafspfund.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/NationalFoodPolicyPlanofActionFINAL.pdf (accessed May 20, 2018)

The National Council of Applied Economic Research. 2015. “Evaluation Study of Targeted Public Distribution System in Selected States.” p. xv. http://dfpd.nic.in/writereaddata/images/TPDS-140316.pdf (accessed May 20, 2018).

NITI Aayog Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office, Government of India. 2016. “Evaluation Study on Role of Public Distribution System in Shaping Household and Nutritional Security India.” Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office Report No. 233. http://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/Final%20PDS%20Report-new.pdf (accessed June 14,2018).

Oxfam and Save the Children. 2011.”Rapid Assessment Report—Floods and Heavy Downpour in West Bengal, India.” http://www.sphereindia.org.in/Download/Rapid%20 Assessment%20Report%20WB%20Flood%20(oxfam%20&%20SCBR).pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

Prasad, E., and N. Mukherjee. 2014. “Situation Analysis on Floods and Flood Management.” International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland. https://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/situation_analysis_on_floods.pdf (accessed May 16, 2018).

Public Distribution System, Govt. of West Bengal. https://wbpds.gov.in (accessed May, 2018).

ReliefWeb. 2009. “Situation Report West Bengal Floods.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ED5E08CD25802034C125761F00469C70-Full_Report.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

Sphere India. 2011. “Joint Flood Assessment Report West Bengal.” http://www.sphereindia.org.in/Download/Joint%20Flood%20Assessment%20Report%20(bankura%20&%20E-medinipur).pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

Sphere India. 2015. “Joint Needs Assessment Report West Bengal Floods.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/west-bengal-jna-report-august-2015_30-08-2015.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

Tapsell, S., S. McCarthy, H. Faulkner, and M. Alexander. 2010. “Social Vulnerability and Natural Hazards. CapHaz-Net WP4 Report.” Flood Hazard Research Centre—FHRC, Middlesex University, London. http://caphaz-net.org/outcomes-results/CapHaz-Net_WP4_Social-Vulnerability.pdf (accessed April 25, 2018).

West Bengal Disaster Management Authority. http://wbdmd.gov.in (accessed May, 2018).

West Bengal State Inter Agency Group in Collaboration with Department of Disaster Management, Government of West Bengal. 2017. “Report of Joint Rapid Need Assessment South Bengal Flood 2017.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/jrna-report-of-south-bengal-flood-2017.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).

World Bank. 2013. Bangladesh Poverty Assessment: Assessing a Decade of Progress in Reducing Poverty, 2000-2010 [Bangladesh Development Series Paper No. 31], World Bank, Dhaka. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/109051468203350011/pdf/785590NWP0Bang00Box0377348B0PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018)

World Bank. 2017. “West Bengal Poverty, Growth & Inequality.” http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/315791504252302097/pdf/119344-BRI-P157572-West-Bengal-Poverty.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018).