Chapter 1

Finding and Developing Ideas

■ What is a Documentary?

Documentary as a form has many points of origin. Some people look to Robert Flaherty’s footage of Inuit life in Northern Canada in Nanook of the North (1922), others to works by Dziga Vertov and his innovative portrait of urban life in the new Soviet Union in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). For many others, the edifying documentaries of the 1930s British documentary movement, described by founder John Grierson as a “creative treatment of actuality,”1 still serve as defining models for today’s documentarians. Wherever we locate its origins, at its most basic, documentary film offers us some kind of vision of how the real world looks and operates. Documentary filmmaking is a fascinating pursuit because it allows us to comment on our society, offers us a glimpse of other ones, and may even exhort our audiences to change the world we live in. As we will explore in this chapter, documentary makers use a wide variety of elements including interviews, records made while historical events unfold, archives of sound and image, and even actors to offer viewers something that is both non-fiction and a story.

As we will see in the coming chapters, “documentary” describes a whole field of filmmaking, from educational films to activist ones, from hard-hitting video journalism to lyrical poetic expressions. But every documentary starts with an idea not just about the real world, but about the process of representing reality as well.

■ Where Do Documentary Ideas Come From?

All documentaries start with a moment of insight, with somebody (usually the producer or director) realizing that a particular person, subject, or event would make a great non-fiction film. That “aha!” moment is the beginning of months, or often years, of work. Sometimes it’s a question that won’t let go of you until you explore it more deeply.

For one of our students, Nathan Fitch, that moment came a few months into his time in the Peace Corps. He was working on the tiny Pacific island of Kosrae, part of the Micronesian archipelago. He recounts:

I visited a remote village with several of my fellow volunteers. As I trudged through the hot sand, I saw a man seated in the shade of a coconut palm. He was wearing camouflage fatigues. Eager to test out my burgeoning language skills, I accosted him in the local language, “Len wo. Kom fuhka?” (Good day. How are you?). He squinted up at me, then replied in English flavored with a Southern drawl. “Hey man, I’m doing good. How are y’all making out?” I was shocked, for few of the young people I had met were confident speaking English—especially to a stranger.

I asked the man, “Have you lived in the US?” “Yes sir,” the man replied, “I’ve been in Fort Benning and Fort Carson. Just got back from Iraq a few days ago for some R&R.” “Iraq?” I confirmed. The man nodded. “Yep, stationed right outside of Baghdad. I’m heading back there next week.”

There were many things I might have asked this soldier had I lingered longer, a cascade of questions that would have highlighted my ignorance of the geopolitics of the region that I now called home. Questions like, “Why are you fighting for the US in Iraq, when I, a US citizen, am not?” “What is it like to leave such a peaceful place for the turmoil of war?” “What is it like to return?” It was these questions, and the somewhat guilty understanding that he was serving in my place so that I could be in the Peace Corps, that were the impetus for my documentary Island Soldier (Figure 1.3).3

■ Are Documentary Filmmakers Artists?

In a 2014 essay “Reflections on Getting Real: Debunking Five Myths That Divide Us,” documentary filmmakers Pamela Yates and Paco de Onís write about the common misperception that filmmakers who tackle human rights abuses, or illuminate social issues, are not artists:

We give equal weight to being artists as well as human rights defenders. We know that as we get better and better as artists, we create wider audiences with far greater impact. Because we aren’t just developing a narrative story arc, we are developing ideas across the length and breadth of the documentary film. It’s the interplay of the two that creates dramatic tension. The power and beauty of cinema are our artistic and political tools. Our canvas is global; our palette, the human condition.2

■ Figure 1.1 Rithy Panh uses clay figures, archival footage, and his narration to recreate the atrocities Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge committed between 1975 and 1979 in The Missing Picture.

One only has to look at a documentary like Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture (2013), about the Cambodian genocide, or Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (2008), about the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, to see the incredible range of creative practices that documentary filmmakers are using to tell stories about real-life events (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). While documentaries like these redefine the genre through their nontraditional use of animation, even more traditional approaches have extensive creative dimensions that overlap with those of fiction film, theater, photography, painting, and even music.

■ Figure 1.2 Animation provides compelling visuals for Waltz with Bashir while recreating the traumatic psychological experiences of veterans of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

Every documentary filmmaker has their own process for finding the seeds of a good film. And like most people involved in creative endeavors, many experience self-doubt and some anxiety about their ability to come up with a good topic and stick with it. It can be reassuring to remember, as choreographer Twyla Tharp puts it, that “there are no creative geniuses . . . in order to be creative, you have to know how to prepare to be creative.”4 Many people report that breakthrough ideas came while they were cleaning the house, taking a shower, or out for a walk. But these moments of creative breakthrough can only come when combined with everyday practices that pave the way. For documentary filmmakers, this often means keeping track of the people, social patterns, trends, and events that are occurring in our communities, country, or world. Many have rituals that include things like keeping a journal, clipping (or, increasingly “bookmarking”) articles from newspapers, magazines, or blogs they read every day. As Graeme Sullivan suggests, “art practice can be seen as a form of intellectual and imaginative inquiry, and as a place where research can be carried out that is robust enough to yield reliable insights that are well grounded and culturally relevant.”5 Other rituals keep filmmakers in touch with their creative potential. Filmmaker Luis Buñuel, for example, committed to having coffee with one particular producer every day, and to telling him a story. While not every story was worthwhile, the practice of coming up with a story a day to tell his producer created enough good ideas that Buñuel was able to make at least a movie a year for most of his working life.6 The important thing is that you create a routine that works for you, and that you follow it consistently.

■ Figure 1.3 Nathan Fitch’s film Island Soldier (2016) started from a chance encounter on a small Micronesian Island.

In addition to being curious, documentary filmmakers tend to be passionate and interested in communicating their ideas and experiences to others. Jay Rosenstein, the director of In Whose Honor? (1997), about the controversy around the use of Native American mascots in sports, recounts the moment he realized he needed to make a documentary about the topic (Figure 1.4):

■ Figure 1.4 Charlene Teters, a Spokane Indian woman whose activism sparked Jay Rosenstein’s interest in the use of Native American mascots in sports. Her story became the centerpiece of In Whose Honor?

I heard this woman, Charlene Teters, speak. She is a Spokane Indian, and she was talking about the University of Illinois mascot Chief Illiniwek (Chief Illiniwek is a pretend Indian that dances at football and basketball games). I had never heard an Indian person talk about the mascot. I was kind of stunned, and very moved, and I thought “Everybody needs to hear this.” And so the film became a way for me to try to get Charlene’s voice and her message out to people who couldn’t or wouldn’t otherwise hear it. So sometimes you just learn information that isn’t known, that you think should be known, and you become passionate about spreading those ideas.8

Other filmmakers use the process of making documentaries to better understand their world. When he began the film that would eventually become The Thin Blue Line (1988), director Errol Morris was making a documentary about Dr. James Grigson, a Dallas psychiatrist who had testified for the prosecution in many

Paving the Way for Creativity

On a trip through Europe, video artist Edin Velez came up with a ritual that ultimately helped him conceive of an idea that would define his work for decades to come. He decided to create a collage journal as a way of testing out different ways of layering images in a single frame (Figure 1.5).

For me, creating small works, not necessarily in your primary medium, is one of the best ways to tap into creativity. It’s always nice to set up a certain number of rules, because if it’s too open people tend to flounder. So I decided that each page had to be finished before I left the location I was in, and I could only use photographs I took or other things I found in that location. It was very freeing to make the journal, because unlike making a video, where you’re concerned about showing it to people, this was a very personal book and I didn’t expect to show it to anybody. The beauty of allowing yourself moments to explore is that out of all this you will have ideas that will be cheesy, and ideas that make you cringe, but then you will have great ideas you never expected to have. You are focusing on the simple task of cutting and gluing images, but what you are really doing is placing your mind in that creative zone. It puts the mind in a place where it allows concepts and ideas to flow from unconscious to conscious.7

■ Figure 1.5 Using small exercises to stimulate creativity. Filmmaker Edin Velez’s collages (left) helped him develop the ideas about image layering that were later incorporated into his video work. The still frame on the top right is from his highly layered film about the traditional and the contemporary in Japanese culture, The Meaning of the Interval (1987). At bottom right is a frame from Dance of Darkness (1989).

death penalty cases. Along the way, Morris interviewed Randall Adams, one of the “cold-blooded killers” (Grigson’s words) that Grigson had helped put on death row, and his film took a completely different turn. He explains:

As I read about Adams’ story I slowly but surely became convinced that there had been a terrible miscarriage of justice. And then the movie changed. It was no longer a movie of Dr. Grigson. It was a movie about Randall Adams. That was the beginning of close to two years of tracking people down, interviewing them, of doing research. The Thin Blue Line isn’t telling the story of a murder case, it’s not about an investigation. It is an investigation! The investigation was done, in part, with a camera—culminating with David Harris’ confession to me. It was on tape—following the malfunctioning of my camera in my interview with him—the tape on which he essentially confesses to the murder! 9

■ Your Artistic Identity

Whatever topic you choose, your film will be different than somebody else’s documentary on the same topic. This is because we each have a particular set of experiences and worldviews that shape our artistic identity.

How do you discover your own artistic identity? This is a lifelong process, and your own artistic identity will evolve through every creative endeavor you take on, starting with the very first films you make as a student. It can be helped along by forcing yourself to think through your own ideas and opinions about your subjects, investigating where and how you have developed your particular point of view, and grounding your film in your own unique stylistic approach (Chapter 2). In Directing the Documentary, Michael Rabiger creates a “self-inventory” that helps readers understand the marks their life experiences have left on them, and translate that into a worldview that is reflected in their films.10 What are your “hot” issues, the ones that will prompt you to engage, question, and communicate with an audience? Discovering these is critical to your development as an artist.

Many documentary filmmakers report that while their topics change from film to film, there are consistent deeper themes that permeate them all. Whether your films will be built around the complex dynamics of family relationships, the quest for identity, struggles for equality, or some other theme is something you will have to discover for yourself.

One of the biggest obstacles to finding your artistic identity as a documentary maker lies in the prevalent notion that documentaries should be “objective” and refrain from having a point of view. If you start with a point of view, it is thought, you risk losing objectivity and risk distorting the truth. Documentary is often misunderstood as a form of news reporting, which is constrained by television network practices of representing “both sides” of an issue, and where editorializing or personalizing is discouraged. Since most situations in life involve more than two sides, and presenting life in its complexity is part of good documentary filmmaking, it’s helpful to jettison this idea of objectivity and replace it with a sense of fairness—to your audience, to the subjects of your film, and to yourself. Reaching a real understanding of the world around us, and the relations of cause and effect in it, can only be seen as a dynamic and ongoing effort. Documentaries have the potential to explore the personal and human dimensions of issues, incorporating layers of information that are broader than the facts journalists traditionally work with. If documentary filmmaking is indeed “the creative treatment of actuality,” that creativity is fueled by your individual passion and perspective.

The best documentaries are usually made by people who have strong ideas and opinions, but aren’t afraid of changing or revising those ideas when presented with new information. Documentaries are not the last word on a topic; they are better understood as supporting and enhancing the discussions that society needs to have. For example, Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006), featuring former Vice President Al Gore, reframed the issue of global warming in such a compelling way that it became a policy debate. Precisely because it took a strong point of view, it opened doors for a broad public discussion that was heard as far as Washington DC.

■ Research

Once you have a strong story idea, you need to start your research process. You will need to become, at least for the time you’re making the film, an expert in the area you are exploring. You may begin by looking for articles, books, and other sources on the Internet and in the library. If you have access to licensed databases like Lexis-Nexis or JSTOR (often available through universities or libraries), your research will be much more thorough than if you rely on a browser-based search engine (like Google).

Before getting too far into your research, it’s important to find out what other films have been made on your topic. Watching any other films that deal with similar issues will help you find an angle that hasn’t been explored yet. While there is no guarantee that no one else is making a film on a similar subject at the same time as you, your goal is to make something that feels fresh in terms of topic, approach, or perspective.

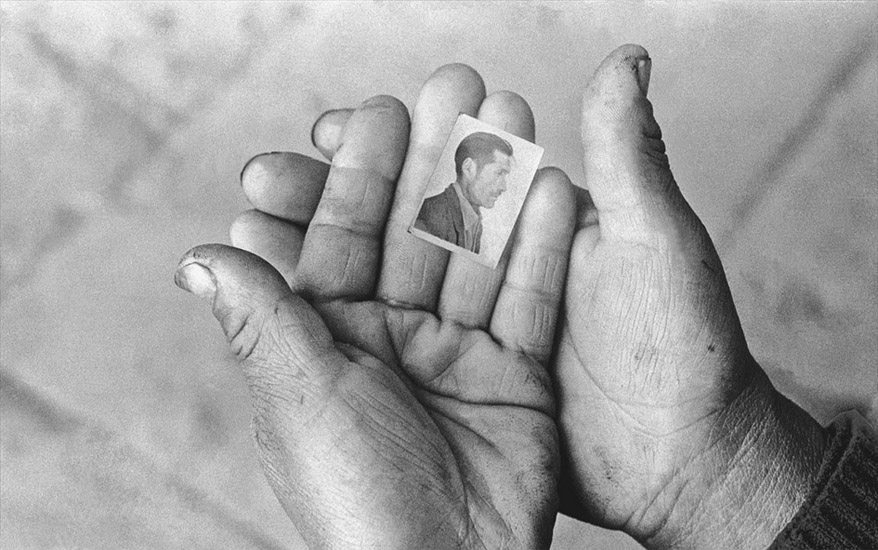

It is also important to find out, in the research phase, what archival footage and stock footage, photographs, and sound recordings exist that you might want to use. This search can be time consuming, but the payoffs can be large. For coauthor Kelly Anderson and Allison Lirish Dean’s film My Brooklyn (2012), about the redevelopment of a popular African-American and Caribbean shopping district in Downtown Brooklyn, finding the photographs that Jamel Shabazz took in Brooklyn during the 1980s (and securing his permission to use them) was essential to setting the mood and tone of the entire film (Figure 1.6).

■ Figure 1.6 Photographs by Jamel Shabazz are essential to the storytelling in My Brooklyn.

Soon, though, you will need to get out of the comfort of your home and start to engage with people in person. Whether they are going to be on-screen, provide you with background information, or simply connect you to other people and resources, a documentary needs people in order to be successful. Sometimes an email approach is the best way to make initial contact, but soon afterwards you should pick up the phone or go visit in person.

■ Research: Where To Begin

Print: Periodic literature (newspapers, journals, magazines)

Online databases

Books on your topic

Primary source documents

Still photographs

Films on your topic:

Good for background information and ideas

Make sure you aren’t reinventing the wheel!

Can provide leads for archival and stock footage (Chapter 20)

Internet: Organizational websites (may have reports, research, white papers)

General Internet searches (and Google alerts)

People: Academics, activists, or other official or unofficial experts

It can be intimidating to go into unfamiliar situations, but as long as you take precautions to stay physically safe, in-person visits will usually yield the best results. On the positive side, there are few things more thrilling than walking into a new environment, seeing things you have never seen before, meeting people and sharing ideas, and building trust. Making a documentary gives you license to talk to people you wouldn’t otherwise approach, and ask questions that might otherwise seem intrusive. Finding people who see the world in ways that help you understand things from new perspectives is one of the joys of documentary work, and anybody who sticks with documentary film making will tell you that for all the difficulty and fear of the unknown that you have to confront, as long as you approach people with humility and respect, the process can be extremely rewarding.

For example, when coauthor Martin Lucas was making the film No Room to Move! (1993) for the United Nations Population Report, he decided to focus on rural-to-urban migration in Mexico. He found himself knocking on the door of a family home in a quiet country town during Holy Week, solely because there was a bright green Mexico City taxicab some 250 miles from home, parked in front. He introduced himself and his crew to the complete strangers who were living there. He says,

I would have never knocked on that door if I wasn’t making a film. But the pressure of knowing I needed an interview subject made me do it, and the cabbie ended up being a great subject for our film. When he heard we were making a film sponsored by the United Nations, and that we thought of him as an expert, he was happy to help out. As it turned out, this man ended up serving another purpose: he knew everybody in the area and became the crew’s “ambassador” as they searched for others to talk with.11

Organizations or professional researchers with an interest in your subject area can be invaluable. For Every Mother’s Son (2004), their film about excessive use of force by police officers, coauthor Kelly Anderson and Tami Gold relied on the attorneys representing their main subjects for information and primary documents such as recordings of 911 calls, crime scene photos, and transcripts of court proceedings. While this material could likely have been obtained by filing requests with the NYPD or the courts, it saved the filmmakers a lot of time and energy to go through the lawyers. And since in this case the lawyers also had an interest in publicizing their cases, the collaboration worked for everybody involved.

For My Brooklyn, Anderson and Dean gained a tremendous amount of information from community-based organizations with an interest in their film’s topic. Several labor-intensive surveys and reports had been published by groups like Families United for Racial and Economic Equality (FUREE) and Good Jobs New York. While it was important for Anderson and Dean to understand that these organizations had their own agendas and perspectives on the topics of development and gentrification, the research found in these documents was invaluable.

Organizations that have spent years working on an issue can also be helpful in identifying possible subjects for your film, and help you gain access to those people. When approaching organizations, the goal is to be transparent about what you are doing and why, and to establish a relationship of mutual trust. This does not mean, however, that you agree to collaborate with them on the vision for your film, or that you will allow them to review the film before it’s made. We will address these issues in more depth in Chapter 5.

Keep in mind that organizations may be understaffed and not have the resources to cooperate with your requests. Sometimes, spending time building relationships can pay off in the long run. Offering to shoot an event for a group (even if it’s something you don’t want to use in your film), or to edit something for their website, or just participating in one of their events or campaigns, can be a nice way to make a relationship more reciprocal.

The situation is different when you are approaching people or organizations who have reason to think your film might portray them in a less than positive light. For public officials, corporate executives, or others in positions of power, it is sometimes best to wait to approach them, since you may only get one chance to get them on camera. People who are used to dealing with the media will need to be approached after your research is done and you have a clear sense of what you want from them, or they can “run away” with the interview, leaving you with little you can use.

Whoever you are approaching, prepare a few (short!) sentences describing what your film is about, why you are making it, and what you hope it will accomplish. Be prepared to answer the question “Why me?” And remember, your job is to listen to them, not convince them you are the expert.

■ The Importance of a Hypothesis

Once you have an idea for a documentary, and maybe some characters in mind, it’s time to develop a hypothesis. Your hypothesis is a basic claim about your subject, and it acts as a map, giving you a way to move forward with your research. Even though your hypothesis may change over time, it’s essential to have because without it, your film will be in danger of losing its focus at any time.

Let’s imagine you decide to make a film about “university tuition increases.” Congratulations! You have found a documentary topic. A topic is an area of interest, but it takes research to turn it into a story you can actually film.

The first thing to figure out is what you are trying to say about tuition increases. Your research will help you develop a point of view on your subject, and also help you narrow down a broad topic to something less abstract. Your sample hypothesis at this point might be:

Rising tuition costs are affecting students.

At this point the hypothesis is based on your gut instinct, but you can’t rely exclusively on instinct. Don’t be paralyzed, however, by the possibility that your hypothesis might not turn out to be true. The point of a hypothesis is to take a stance that you can begin to test.

Let’s say you actually interview some students and they tell you that they are struggling to make ends meet and stay in school. This allows you to restate your hypothesis with more urgency:

Cutbacks and increases in fees are jeopardizing student dreams of a college education.

Now you are convinced there is a problem, but you don’t know how widespread it is. How much has tuition gone up? Are there cases of students dropping out of college that can be attributed to these increased fees?

You find data to suggest that fees have increased substantially and that graduation rates have stalled. You can now move past your previous hypothesis to state:

Cutbacks in financial aid and increases in tuition are actually making the possibility of completing college difficult for a substantial number of students.

Let’s say, as you start shooting, you interview an economics professor who not only studies these trends but has witnessed them in her school over the years. She tells you there is a clear link between public college education and the ability of a society to be viable in an era of economic globalization. You also might spend more time filming with individual students and their families. All this might lead you to a more urgent and dramatic thesis:

Cutbacks and increases in tuition are resulting in the first generation of Americans at risk of being less well educated than their parents, jeopardizing the nation’s ability to be competitive globally.

Now you have a really interesting and compelling point of view, and a point that you think your film will make. While this process of stating and refining what your film is about starts during preliminary research, you must see it as ongoing. As you talk to more people and learn more during your production process, your views will continue to develop and change.

Your hypothesis needs to be something you care about, and your personal stake in it should be clear to you. In the case of tuition increases, you might feel that every society owes its young an equal opportunity, and that this opportunity is under threat. On a more personal level, you might have had to struggle for your own education. Or it might be the opposite: your parents’ sacrifices might have made it easier for you to go to college and you feel like others deserve a similar chance. No one reason is better than another. What is important is that you are aware of your own motivations and values, and that you have a strong sense of where you are heading while continuing to stay open to new perspectives on your topic.

Should you talk to people who will contradict your thesis? The answer goes back to the idea of a documentary as part of a larger conversation in society. Films thrive on conflict, and you will do well to have a variety of perspectives represented. Let’s imagine your college administrators believe that tuition is not a key factor influencing student retention. Including their perspective will likely make your film more interesting and complex, and strengthen your credibility.

■ “Casting” Your Documentary

The next step is to find real people who can embody the issues in a way that puts flesh on the bare bones of your hypothesis. Documentary filmmakers have varying criteria about what makes a person a good choice to feature in a film. Here are some things to consider:12

- ■ Does the person present well on screen? Many directors do a test shoot to see if the person’s personality, passion, or conflicts translate on camera. Some refer to people “popping” on screen, or just being “cinematic” or “charismatic.” The criteria for this will differ from director to director, but there’s no doubt you will come across people who seem like great possibilities for your film when you meet them, only to find they can’t hold an audience’s attention on screen. Being able to recognize this early on will save you (and your subject) time and stress.

- ■ Do they have a goal, and are they willing to let you follow them to try to reach it? It is sometimes said that “action is character.” People who aren’t trying to achieve things, and encountering obstacles along the way, can make for boring films.

- ■ Be careful about quirkiness as a major draw, especially for its own sake. “Colorful” characters can be appropriate for short films, especially if their quirks express something deeper that touches on a more universal theme. For longer films, there needs to be more at stake or it will risk becoming “one-note”—repetitive, and therefore boring.

- ■ Many documentary filmmakers report that they are drawn as they have a personality that is not too guarded, nor too smooth, people whose “performances” of themselves contain cracks that allow us to see their internal as well as their external struggles. This kind of underlying conflict, especially when married to an external goal the audience can relate to, can be perceived by audiences and be deeply compelling.

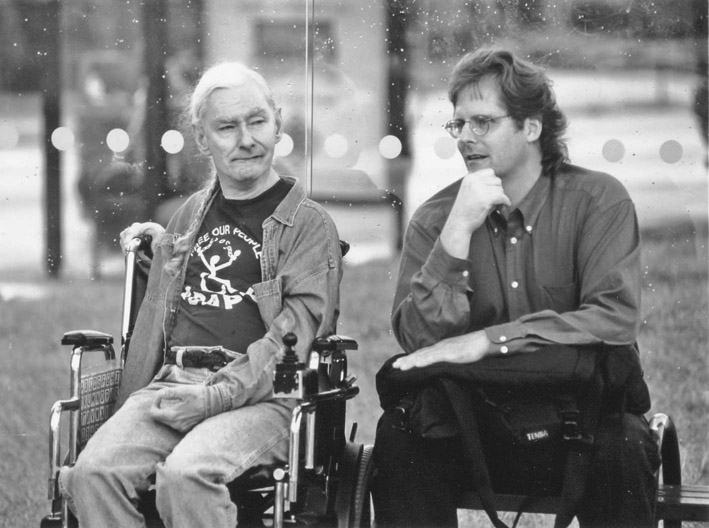

People who are highly articulate can be useful for your film, especially if they are going to fill the role of experts who will be explicating complicated history or information. Don’t eliminate people just because they aren’t traditionally articulate, however. If we never choose people who aren’t “good talkers” to be on camera, we will unintentionally end up excluding whole groups of people from the media landscape. An example of a different approach is seen in Walter Brock’s If I Can’t Do It (1998), about Arthur Campbell Jr., a disabled man who is pushing for independence and equal opportunity (Figure 1.7). Instead of having Campbell’s sister speak for him as an interpreter, Brock allows Campbell to speak for himself, even though it is difficult to decipher his language. Brock explains:

Nothing in my life prepared me for my first sight of Arthur. There he sat in his wheelchair, drooling, arms flailing, making loud noises that I could not imagine made sense . . . I want viewers to experience the discomfort that I felt, to process and examine it, and come out on the other side of that discomfort with a greater sense of acceptance and tolerance.13

■ Figure 1.7 Walter Brock (left) with Arthur Campbell Jr., the main character of his documentary If I Can’t Do It. Photo by Noel Saltzman.

Active vs Passive Characters

Many documentaries begin with a character trying to achieve something that matters to them. The protagonist of In Whose Honor?, Charlene Teters, wants the University of Illinois (and all sports teams) to stop using their Indian mascots. In The Wolfpack (2015), Crystal Moselle’s fascinating documentary about a group of brothers whose father keeps them locked away in an apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the protagonists share the goal of breaking free so they can experience the world outside. Over the course of most documentaries, the characters try to accomplish things, find obstacles in their way, and either succeed or fail in their attempt to surmount the obstacles. To maximize the possibility that your film will be dramatic, look for people who are trying to do something about their circumstances, not people who are passive victims of circumstances beyond their control. Another way to think of this is that you want characters who are closely involved in the issue you are exploring. While there is a role for secondary characters, there is no substitute for subjects who have something deeply significant to them at stake.

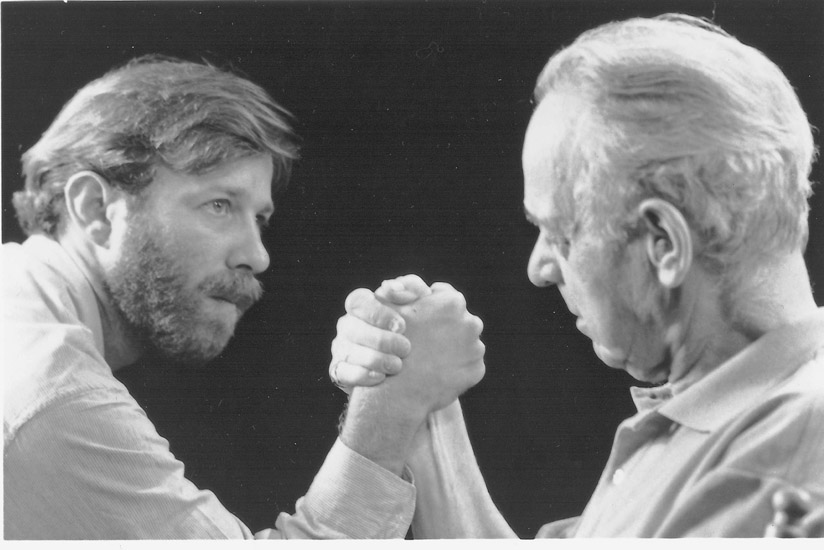

Sometimes, people who are more passive than active can function in a dramatic way. Nobody’s Business (1996), an experimental documentary by Alan Berliner, would seem to be about Oscar Berliner, the filmmaker’s father. Oscar is a tragic character, seemingly victimized by age, lack of friends, and life circumstances. If he were the film’s only subject, this would likely present problems. But the other main character in the film is the filmmaker, Alan. In this interview, he explains how his father’s passivity was actually what motivated him:

The kinds of messages I was getting from my father were becoming very difficult for me to accept: That the misfortunes of his life had overtaken him. That he had somehow become a victim of circumstances . . . Oscar Berliner cannot live for 79 years and tell me his life is nothing, was nothing. I’m much too alive as a human being to accept that attitude from him. So the more he articulated his own ordinariness, the more motivated I became to prove him wrong.14

The filmmakers’ need to challenge his father about precisely his passivity becomes the conflict that drives this highly dynamic and entertaining film (Figure 1.8).

Not all documentaries follow characters over time. Documentaries can take many forms, and conflict can also be metaphorical, a conflict of ideas or theories about how the world works. An example of a more conceptual conflict would be Charles Ferguson’s Inside Job (2010), about the 2008 financial crisis, which we will discuss further in Chapter 3. The important thing is that there be something at stake for you, for your characters, and for your audience.

■ Figure 1.8 Alan Berliner’s active efforts to pull out the story of his extremely reticent father provide the central conflict that is the engine of Nobody’s Business.

Juggling Multiple Characters

Often filmmakers cast a wide net, filming multiple characters and narrowing the list down over time. Sometimes a subject ends up “on the cutting room floor” because the actual course of their story hasn’t produced enough interesting conflict. Remember, we are dealing with reality here, and nobody can predict for certain what will happen in the course of filming. At other times, you reframe your topic as you get more information, and a character who seemed essential in the beginning ends up being less important.

■ Figure 1.9 Every Mother’s Son follows three mothers (from left, Doris Busch-Boskey, Kadiatou Diallo, and Iris Baez). Each character represents an aspect of the problem the film illuminates. Photo by Anna Curtis.

It can be taxing for audiences to follow multiple characters, so casting sometimes involves making sure each character is distinct from the others and carries a specific part of the story you are trying to tell. For Every Mother’s Son, Anderson and Gold followed four mothers for several years before deciding their film could only accommodate three main characters. “People were confusing two of the characters’ storylines,” says Gold. “We ultimately decided that each of the women needed to be very different—physically and in terms of the details of their story—in order for people to not get confused.”15 They also decided that, even though in reality there was a lot of commonality between the women’s stories, each mother’s story as presented in the film needed to illuminate one aspect of the issue of police brutality, without a lot of overlap. Gold says,

Iris Baez’s story became about how difficult it is to have abusive officers removed from the force, Kadiatou Diallo’s story became about racial profiling and the ways that aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics can lead to disaster. And Doris Busch-Boskey’s story illuminates the ways incidents of police abuse are covered up, and victims of police abuse are demonized. Together, the three cases allowed us to address a very complicated situation in an accessible way, and telling it through the mothers’ points of view made it emotionally compelling for audiences” (Figure 1.9).16

■ The Value of the Documenting Process

While interviews are a common staple in documentary, real events and processes that can unfold in front of the camera will be uniquely compelling to audiences. Using the tuition example, imagine you discover that students are planning to interrupt a meeting where university trustees are expected to approve a tuition increase. This situation would seem an important dramatic addition to your story. Or you could take another approach, starting your tuition story with a shot of a student moonlighting at a fast food outlet, throwing out the trash in front of the store at 2 AM, and then studying at a table. A scene like this would give your viewers an idea of the difficulties of student life. It could also be used to support the testimony of students, parents, college officials, and others you might interview.

One key point is that the image of the student who is working nights puts a face on the larger issue. Documentary stories are best when about people, not “issues” or “problems.” A specific person shown in their daily environment, or a concrete situation, can illuminate the larger issue in a way that resonates. It is the specific details and the nuance that make the story worth watching for others.

■ Feasibility

It’s important to be realistic about what you can accomplish with the time and resources you have available to you. There is no point in embarking on a history of the origins of the Vietnam War if you have three months and no budget for clearing archival photos. If family commitments, job obligations, or finances limit your ability to travel, it makes sense to choose a subject close to home. Following a documentary story often means you need to drop everything and run to shoot an event that is unfolding, and taking geography into consideration is wise.

Similarly, you need to make clear to possible film subjects that there will be some real time commitment when they agree to be part of your film. Filming with someone who is impatient to see you gone is likely to produce unusable material.

Finally, institutions can make life tricky for filmmaking. Schools, hospitals, and other government agencies can be suspicious of press and concerned about negative publicity, not to mention genuinely concerned about the privacy of students, patients, or clients. You need to make sure that before investing a lot of time in a story that relies on access to such institutions, you have permission (in writing) to film.

It is also important to make sure that you have explicit permission to film with your subjects, and the traditional and still the best way to do this is with a written release form (Chapter 5). You don’t want someone to decide two months into filming that they no longer want to participate. You should be particularly careful with minors, where you will need to get parental permission and expect constant supervision.

■ The Specific and the Universal

It is important to remember that making a documentary film means creating a story that draws on the realities in front of your camera, for an audience that doesn’t know the specifics, or what is at stake, or even why they should care. You may not be able to predict how your film will reach its audience, but you can make a story that has the potential to speak to universal themes. Every good story should have the potential to resonate on multiple levels, and part of your skill as a storyteller involves maintaining an awareness of the links between the specific reality in your film and the universal issues that you understand as being at stake.

An example is Paco de Onís and Pamela Yates’ State of Fear (2005) (Figure 1.10), about the Peruvian government’s war on the Shining Path guerrilla group. The film documents how a legitimate fear of terrorism was used to undermine democracy, making Peru a virtual dictatorship where official corruption replaced the rule of law. Although the film was made entirely in Peru, and didn’t address the international context at all, people in other countries found it resonated strongly for them as well. De Onís explains:

We got an email from a guy in Nepal who said he had read about State of Fear, and it sounded a lot like the story of Nepal. Because they had this king, King Gyanendra, and he said he reminded him a lot of Fujimori (in Peru). He said he’d like to screen the film in Nepal, so we sent it. And he said at the screening, you could hear a pin drop. Everybody was looking at Peru but thinking “this is Nepal.” So then he asked if they could make a Nepalese version of the film, doing a voiceover, and we said “sure.” They used it in organizing meetings for months, as a way of talking about what was going on in Nepal. He was part of a pro-democracy group, and they eventually prevailed.

State of Fear was about Peru. We never mentioned other countries, or US influence or anything like that. It was about their own war on terror, as they themselves describe it. Their truth commission was looking back on 20 years of the war of terror, and we were just entering the global war on terror. The film got translated into 48 languages. It went to 154 countries, because every country in the world was grappling with this “security vs. civil liberties” thing. It just resonated everywhere.17

Not all documentaries translate across cultures and countries this dramatically, but you should always be asking yourself what the larger themes are in your work, and how they will translate to people beyond you and your team.

■ Figure 1.10 State of Fear was about Peru from resonated in Nepal because of its universal themes. Photo by Vera Lenz / http://skylight.is.

■ Research Checklist

- Come up with possible topic:

- Is there a reason to make this documentary? What will it contribute to the public’s understanding of the subject? If other films exist on the subject, can you show it from a new angle?

- Is there conflict, a clear struggle over something that matters? What is at stake at a local level, and in terms of the big picture?

- Is there an unfolding story that you can capture as it’s happening? It’s much easier and more powerful to capture in the present than have people telling what happened in the past (though often you end up with a lot of this anyway).

- If you are telling a story that happened in the past, are there people who can tell what happened from their personal experience? Others (historians, for example) who can talk about it? Can you find visual documentation (archival footage, stills) that you can use to help tell the story?

- What is the main point you want to make with the film (your “hypothesis”)? Keep revising this as you research and even as you shoot.

- Is there one or more organizations you can work with? How can you build trust and a relationship with them? Can they connect you with people and help with research?

- Is it feasible? Can you get access to the places and people you need to make it? Do you have the written permissions you need to actually film with the people and in the locations you need?

- Do you have the financial resources to back up your project? Have you looked for hidden costs like archival rights, or travel expenses, or equipment rentals that may present obstacles later?

- Research

- Using the Internet, publications, phone calls, and meetings with people, find out as much as you can about your topic.

- Meet with potential organizations and people who can help you. Be sensitive about taking up their time. Do not promise them the world. Be clear that you are not working for them, but that you are interested in their input on your idea. Ask them if they are willing to share resources (information, research, contacts) with you. Identify a contact person at the organization that can be your liaison.

- Identify possible events to shoot. Get permission to shoot them.

- Identify key players on the issue who you can touch base with periodically to find out what’s happening in the world of your subjects.

- Identify people to interview. (You do not have to do pre-interviews on video, but you should meet them or talk to them on the phone.)

- Build relationships with anybody and everybody you need cooperation and trust from.

- Find archival footage sources for material you might need, newspaper articles, still photos, etc.

- Keep refining your perspective on the issues and revisiting your hypothesis.