Chapter 5

Documentary Ethics and Legal Issues

A documentary film production involves an intense and often intimate interaction with the real world. It is an encounter with other human beings, many times in complex and difficult circumstances. And it is an attempt to represent aspects of that world to a larger audience. In addition, documentaries often incorporate the creative works of others, which forces you to confront issues of ownership and authorship. All of these circumstances offer particular ethical and legal challenges.

Why do we need “ethics”? In the largest sense, ethics suggests some kind of common code of conduct for morally correct behavior. Documentary filmmaking involves real people who can be misrepresented, exploited, or otherwise harmed by your actions. When we are representing others, we are taking responsibility for how they are seen in the larger public sphere, often by millions of people. In addition, we are showing audiences a picture of the world that we claim is valid. How do we understand our responsibility to an audience that is depending on us to raise issues in a useful and truthful way?

An ethics of documentary would fall under the category of “applied ethics,” akin to legal, medical, and journalistic ethics where philosophical and moral principles are applied to real-world situations. But documentary makers don’t have boards, licenses, or one organization that we all belong to, like the American Medical Association (AMA) for doctors. Nor do we take any professional oath. Is there a specific need for a set of standards like other professions maintain? Because documentary filmmaking is so varied in practice, it would seem impossible to create such a specific code. However, the issues that face documentary filmmakers are as morally complex as those of any other profession, and the implications can be just as serious.

■ Responsibility to Your Subjects: Subject Relations and Release Forms

In documentary filmmaking, the relationship between you (the representer) and your subject (the represented) is by definition unequal. As the filmmaker, you hold most of the power. This relationship is formalized in the release form you ask people to sign when you begin filming with them. A release form is a legally binding contract between the filmmaker and the subject being filmed, stipulating that the subject consents to being filmed and included in the final work. Releases are generally worded very broadly, so that filmmakers can use the footage for promotion, or reassign rights to third parties. Many beginning filmmakers find asking someone to sign a release form daunting, but it is critical that you get releases. Networks and distributors will not enter into an agreement to show or distribute your film without a full set of release forms. Contrary to popular mythology, asking someone on camera to say they grant you permission to use their interview will not be considered sufficient by most broadcasters and distributors. In addition, having a signed release protects you from legal challenges over privacy and libel. For sample release forms, see our companion website (www.routledge.com/cw/Anderson). While specifics vary from country to country, the standard release forms are similar in the United States, the United Kingdom, and other Commonwealth countries.

■ When Do You Need to Get a Release?

While some networks might insist that every person whose face you see in a documentary must be covered by a signed release, most typical practice suggests that you need a release in a situation where someone actually speaks with you. A variety of courts in the United States have made decisions that someone whose picture is taken while on a public street cannot sue an artist for the use of their image.1 In many situations where documentary filmmakers work, however, the space is not public. A football stadium, a nightclub, a hospital—all these will present specific issues. One common answer for events or crowded spaces is to post a sign indicating that there will be filming, and that entering the locale indicates consent. Often this will be combined with a suggestion to stand in a certain area where the camera will not be pointed if you don’t want your image to be taken. Schools also raise specific issues, because children are minors. Filming children in a classroom will require getting a consent form signed by the guardian of each child in the class. Other schools take the precaution of getting blanket consents from parents at the beginning of the term. Hospitals raise other issues, as patients have specific legal privacy rights.

In addition to obtaining releases from people, it is usually important to obtain a location permit when shooting on private property or any kind of institutional or restricted locale. There is more on location permits and agreements in Chapter 6.

Veteran documentarian Tami Gold suggests that getting a release is not so much an unpleasant chore as it is a key step in building a productive relationship of mutual trust:

The big challenge for documentary filmmakers is building relationships. One of the reasons I love release forms is that asking for the release stops the process and allows the person to think. It establishes a contract. It basically acknowledges that they have rights, and they might not feel comfortable signing them away, but some of it can be negotiated. I’m not saying it’s easy. Sometimes it’s hard to go to people and ask them for permission to use their image or their interview. On the other hand, it is our responsibility to take their rights seriously, and be clear about the terms of the relationship.2

Gold’s dynamic understanding of the maker’s relationship to their subjects underlies good filmmaking and richer storytelling. Why? Because a documentary film is only as good as the filmmaker’s relationships with their subjects. The more people trust you, the more willing they will be to invite you into their lives in difficult moments and to share their deeper feelings with you on camera.

The introduction of the release form is also your chance to discuss the long-term relationship between you and your subjects. For many filmmakers, this is the point where you can negotiate other questions involving editorial control and how much involvement you are willing to offer. Are certain topics off-limits? Will you show subjects a cut before exhibiting the film? Will you offer them some level of control? Despite a shared perspective you may have, and your efforts to treat people fairly, your goals as a filmmaker are never identical with those of your subjects. Often the process of filmmaking is a strong bonding experience, and it is important to establish boundaries early on so that subjects don’t later expect something you can’t or won’t deliver.

It is not uncommon for a subject to have second thoughts about being in a film, especially if their situation changes or tension develops with the filmmakers. Without a signed release, a subject can legally and legitimately insist on being removed from the project, leaving you in one of the worst binds filmmakers can find themselves in.

Even when you have consent, participants can feel misled. French documentarian Nicolas Philibert selected Georges Lopez and the students in his one-room rural school from over a thousand possible schools to be the focus of a film, and then spent seven months filming with him and his pupils to make the hit documentary Etre et Avoir (2002) (Figure 5.1). The film was a big success, and brought in some 2 million euros for its producers.

■ Figure 5.1 Georges Lopez, a teacher in a French village school, is the main character of documentary Etre et Avoir (2002). The film’s success led him to sue the filmmaker.

In a lawsuit waged by Lopez against the film’s producers, Lopez claimed he was not given a clear picture of the scope of the project, and demanded 250,000 euros on the grounds that the film was partially his creation and that his teaching methods were his intellectual property. Philibert in return asserted that “one of the founding principles of documentary filmmaking is to not install relationships of subordination. If you start paying people in documentaries, they become your employees.” The French court ruled against Lopez, noting that he was basically doing what he would normally do: teaching kids. Lopez didn’t pick shots, or define the film’s approach. He did spend time answering questions, but again, that is typically what interviewees do in documentaries, and he had given his consent for that.3,4

The film’s producers did offer Lopez some money by way of settlement, but he turned it down. They had also done something rather atypical initially: they had contributed support to the school itself. While it is difficult to draw general conclusions from one case, it is worth remembering that as a filmmaker, you should try to present a realistic sense of what the outcomes might be for participation in your film project.

One important way of thinking about this comes from social science research; it is the idea of informed consent. This principle suggests that you make it clear to your subjects what your film is about and what their role will be, and what the possible consequences of participation might be. The practical realities of merging these ethical standards with normal production practice are difficult but worth contemplating. In addition to making ethical sense, informed consent is prudent for the filmmaker. Contracts are only binding if both parties understand what they are signing. If a subject who appears in your film shows up in court and says, “They just told me I had to sign this and never explained what it was,” they may have a case.5

Producer and attorney Andrew Lund makes the point that in order for your subject to grant informed consent, you need to understand the release form yourself. Pulling a release form off the Internet and handing it to your subject is not responsible or reasonable. Take time to understand exactly what the release says before presenting it to anybody. Finally, make sure the release asks only for what you really need. Lund says:

Some release forms are much broader than you need, and asking subjects to sign them can be damaging to your relationship. Many releases give the filmmaker the right to reassign the rights to use the footage to any third party, regardless of who they are and what they are using it for. A subject should be able to agree to be in your film, and grant you any rights necessary to distribute your film, without giving you the right to license the footage for use in a beer commercial! It’s not hard to craft an agreement that allows you the rights you need to make and distribute your film, without making your subject unnecessarily vulnerable.6

Who Gets to Represent Whom?

Questions of voice, authority, and authorship became a serious concern among anthro-pologists in the 1950s, and the concerns flowed through to documentary filmmaking. Who can represent someone else, and with what intention? These questions are even more acute when we consider that documentary filmmakers often come from more privileged environments than those they are representing, and that simply having the means, training, and outlets to represent others creates an inherently unequal power dynamic.

■ Figure 5.2 Zana Briski, the director of Born Into Brothels, with one of the Indian children who were her subjects. Photo by Tumpa.

Zana Briski, the director of Born into Brothels (2004), started by teaching photography to the children of Indian sex workers in Kolkata (Figure 5.2). In the course of her work, she became deeply involved in the lives of the children who were the subjects of her Academy Award®-winning film. She ended up not only using the images taken by the children to describe their reality, but transforming their lives extensively, even taking them on trips abroad and getting them into boarding schools. Although money generated by her project provided real opportunities for at least some of the children, the film triggered a storm of criticism in India.

In their advocacy of Sonagachi’s children . . . the directors have turned the tables on their mothers (and fathers). We see them at their worst: drugged, screaming at the children, shooing them away when clients arrive, fighting with one another, obstructing Briski’s efforts to give her students a future. If the children of Sonagachi enjoy moments of intimacy or comfort with their parents, we are not privy to them. It may just be possible that this is, in fact, the reality of the lives of the children Briski documents. No effort, however, is made to lead the audience into the shoes of the sex workers: Born into Brothels reduces them to props.7

Others felt her approach was paternalistic, a criticism that resonates particularly strongly, given the history of colonial domination in India. A review in the Indian national magazine Frontline summarized this criticism: “If Born into Brothels were remade as an adventure-thriller in the tradition of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, its posters might read: ‘New York filmmaker Zana Briski sallies forth among the natives to save souls.’”8

While for some Indians Briski’s film had a paternalistic flavor, it can also be said that as an outsider, she was offering a voice to children who would otherwise live their lives in the shadows of a society that offered them no voice and no future. Before making the film, she spent three years working with the children on photography projects, and she continued to work with them, even setting up a foundation to help support their life goals. For her, the involvement and the effort to empower specific children highlighted a terrible inequality. And the specific act of giving the children cameras and encouraging them to see and document the world around them was empowering as well as very moving for audiences, as the film’s many awards attest.

One solution to the problem of relating to subjects is to have the community represent itself. In the late 1960s, new portable video equipment first made filming by nonexperts possible, and documentary makers such as George Stoney, working with Challenge for Change and the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), developed a documentary approach that put the camera in the hands of the communities being represented. Films like You Are on Indian Land (1969) and VTR St. Jacques (1968) allowed people to represent their own situations and represented a notable breakthrough in the understanding of local issues and marginalized communities.

While self-representation is an important development in documentary history, it does not necessarily guarantee a good film. Often people will represent themselves the way they want to be seen, rather than in the most insightful way. Many of the best documentaries create a picture of a situation from multiple, often conflicting, points of view. For this and other reasons, most documentary filmmakers still end up in the more ethically challenging situation of representing others. This is not necessarily negative. An outsider can often see patterns and relationships that the people involved cannot see clearly. This is particularly true in our modern era of globalization where even the most local issues can be affected by outside players and forces.

■ Figure 5.3 In Darwin’s Nightmare, director Hubert Sauper draws on a range of local knowledge and knits it into a dense tapestry based on his outsider perspective on the situation in Tanzania.

Some films, although made by outsiders, can be very helpful in creating an understanding of the predicament a community is facing. In Hubert Sauper’s Darwin’s Nightmare (2004), the residents of a fishing town on the shores of Tanzania’s Lake Victoria live harrowing lives, exporting giant fish, surviving on the edge of starvation, devastated by AIDS and poverty, while the wealth they produce flows to European arms manufacturers supplying endless African wars (Figure 5.3). Sauper makes a point of building his investigation with local knowledge from interviews with people others would overlook: security guards, street kids, prostitutes, as well as foreign pilots and factory owners. By bringing all of these players together with an eye towards the larger picture, the filmmaker helps us see that this is not a local problem, but a perverse system in which globalization as well as the demands of normal European and American consumers are the core problem.

At other times, outsiders can tell a story that would be unsafe for locals to expose. An example is Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country (2008), a film by Danish director Anders Ostergaard about undercover video journalists in Burma. The film could not have been made by filmmakers within that country because of the repressive nature of the government. It was nominated for a Puma Creative Impact Award for “putting the issue of Burma firmly on the international agenda,” “helping to bring about the release of [opposition leader] Aung San Suu Kyi,” and “inspiring a new generation of VJs and independent journalists within Burma.”9

There are simply no hard and fast rules about who gets to represent whom, and under what circumstances. Probably the best advice is to think seriously about the privileges you have and consider the impact of your filming on those you are representing. Ask yourself why you want to do the story you are doing. In Directing the Documentary, Michael Rabiger suggests you check your “embedded values,” and ask yourself key questions about your assumptions about class, race, appearance, speech, and background. Also, try to consider how you are representing the environment, family or social dynamics, and who has or gets authority in your work.10

Of course, many times, power relations will be reversed and filmmakers will find themselves speaking with subjects who represent power and authority, whether social or political. How do our obligations to them differ? Legal opinion in the United States suggests that public officials can be held to different standards based on the public’s “right to know” in a democratic society, including a higher burden of proof for libel, which means that you may be on safer ground exposing information about them than about a private citizen.

But what about people who are not political figures? Very often, documentary filmmakers find themselves in the position of making the lives of the rich, powerful, and privileged uncomfortable. Here, the rights of individuals might be trumped, at least for the filmmaker, by the greater good. In Inside Job (2010) for example, filmmaker Charles Ferguson feels free to put his interview subjects, who are some of America’s key financial players, on the spot, to the point where some of them walk off the set to escape his grilling. His logic is that these are the extremely powerful members of the financial community, the government, and academia whose collusion allowed the 2008 financial crisis to take place, so why ask only softball questions that allow them to use his film as another opportunity for a PR spin?

In real life, of course, people fall on a spectrum in terms of how much power and responsibility they have, and documentary filmmakers are no exception. This means that you as a filmmaker will always have to make difficult decisions. These decisions will resonate out in the world, so make sure that you can live with them.

The Impact of Money

Paying subjects is a deeply thorny issue in documentary circles. It is anathema in journalism, because it is considered to compromise the integrity of the source. But in documentary, you are sometimes asking people to be involved with your project for weeks, months, or even years. While most documentary filmmakers do not pay their subjects directly, they may seek to compensate them in some way for their time. Whether this happens before production or after the film is completed varies. We do know anecdotally that some filmmakers feel an ethical responsibility to the people whose stories make their films possible, and that sometimes this translates into a financial giveback. A very public example would be Zana Briski, who as mentioned above actually set up a foundation to fund the educations of the children who are featured in Born into Brothels (www.kids-with-cameras.org). One big problem with paying people up front is that it may make them feel obligated to spin a story to meet your expectations. A workaround is to pay subjects for exclusivity, compensating them for not offering their story to another media maker for a specific period of time.

Another key principle derived from journalistic ethics is that you should not accept support from sources who have an interest in how things are represented in your film. The Radio-Television News Directors Association cautions against “accepting gifts, favors, or compensation from those who might seek to influence coverage.”11 This is a tricky area for documentary filmmaking, where funding is hard to come by and where it is common for an organization interested in a specific topic to support media production about that area. It is up to you to be clear with funders that you plan to stay independent and represent things as you see them. Be aware that if there is any possibility of exhibiting on US public television, you will be dealing with strict guidelines for funding from interested parties. According to PBS, these guidelines are intended to ensure that:

editorial control of programming remains in the hands of the producer, that funding arrangements will not create the perception that editorial control was exercised by someone other than the producer, or that the program was inappropriately influenced by its funding sources.12

Handling Delicate Situations

Because many documentaries deal with subject matter that is controversial or that exists at the margins of society and legality, you will undoubtedly need to confront situations where it’s unclear whether you should film or not. These include:

- Situations where people are doing something illegal

- Situations where violence is occurring in front of the camera

- Surreptitiously gathered images

- Illegally obtained footage

- Situations where your footage may put the subject at risk

All of these situations present moral dilemmas. Filming people injecting illegal narcotics, for example, can be seen as damaging to their reputations, putting them at legal risk, and gratuitous (meaning you are showing the act for sensational reasons that are not integral to the story). But the same material might also be significant as a way of representing a social reality that many would rather ignore. It depends on the context you establish, and the relationship of the scene to the overall thesis of your film. Only you can make the decision, and decide that you are including potentially sensational material for the right reasons.

Obtaining material illegally seems like an unwise thing to do, and it can be. But what if you are a journalist who gets inside information about malfeasance in high places? You may feel that there is a “right to know” that overrides the government’s information restrictions. For example, laws promoted by agricultural interests in Utah and Iowa have made the recording of undercover videos showing animal cruelty in farming practices illegal. You might decide that breaking this law to expose inhumane farming practices is a risk you are willing to take in the interest of public education and debate on the issue. Clearly we can’t advocate breaking the law. You should assess the risks of any potentially illegal action for yourself.

The same is true for images that are gathered surreptitiously. In the case of Ying Chang, Peter Kwong, and Jon Alpert’s Snakeheads (1994), the filmmakers were trying to explore illegal trafficking in indentured labor and posed as labor contractors. They arranged a meeting with traffickers in a restaurant in China, and filmed the meeting with a hidden camera (Figure 5.4). They used the material in the film to show how brazen the trade in human beings is. We see them bargaining over price, quantity, and delivery dates, creating incontrovertible evidence for the existence of the trafficking problem they are highlighting.

■ Figure 5.4 This meeting with labor traffickers in a restaurant in China was filmed with a hidden camera for a documentary exposé of the trade in human beings, in Snakeheads.

Putting your subjects at risk by, say, outing them as lesbian or gay, is something else you need to discuss with them before it happens. Similarly, there are times when subjects may be put at risk because of repressive governments or other social factors, and speaking publicly may lead to retaliation later. While you can never be sure of the consequences your film will have, it is crucial that you think these possible outcomes through and be as responsible as you can.

■ Responsibility to Your Audience: Objectivity and Fairness

Ethics also involves your responsibility to a viewing public. Here is where terms like bias, balance, and objectivity are commonly discussed. There are important overlaps between documentary practices and journalistic ones, and important differences.

In decades of teaching documentary, the authors have found that students cling to the idea that documentaries should be “balanced” and “objective,” meaning that they should not take sides or claim a strong position, especially one far outside of the mainstream. This problematic expectation emerges from the history of American television news. As Barry Hampe states:

The very notion of objectivity in documentary is a fairly recent development in the history of the genre. It is an outgrowth of the peculiar rules governing American network television, and a basic misunderstanding of both the requirements of journalistic objectivity and of the nature of scientific objectivity. Certainly the pioneers of documentary made no pretense of using a journalistic approach in their films, and would have found any discussion of journalistic “objectivity” totally irrelevant. They unashamedly used the documentary to make as powerful a statement as they could manage about something they considered important.13

The early Soviet documentaries, as well the British documentaries described in Chapter 2, would seem to support this claim. The way journalists tend to approach balance is by giving a counterpoint to every point. The problem with this is that a false balance can actually obscure reality. For example, even though 99 percent of scientists believe that global warming is caused by human activities, a study of articles in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, and The Washington Post between 1988 and 2002 showed that 53 percent of stories gave equal attention to scientists who claimed global warming was a natural phenomenon.14 This fulfilled the need for balance, but created a false impression of controversy in the scientific community, where actually there is strong consensus.

For contemporary documentary filmmakers, ideas of objectivity and balance have largely been replaced by one of “fairness.” We can still borrow certain principles from journalism, such as the idea that facts should be verifiable. You should resist omitting or obscuring evidence or information that contradicts your central claims. Anderson and Gold’s Every Mother’s Son (2004), for example, was built around the idea that the young men killed were innocent. If the filmmakers had discovered, in the process of making the film, that one of them had actually been carrying a gun, or was involved in a crime at the time they were killed, it would have been inappropriate and misleading to eliminate those facts from the film’s representation of the events.

The line between what is acceptable and what isn’t can be blurry. Michael Moore ignited a huge controversy when he manipulated the chronology of events in his film Roger and Me (1989). He claimed that a cash register was stolen during Ronald Reagan’s visit to an Italian restaurant, but it had been stolen a few days earlier. Moore portrayed the construction of the Auto World theme park and a Hyatt Regency hotel as happening after the mass layoffs of General Motors workers in Flint, Michigan, in 1986, when in fact they were built before. Moore dismissed the criticism as a nonissue, arguing he was making a “movie” rather than a news documentary.15 Some critics called Moore to task for these lapses, while others defended them as necessary for exposing the “larger truth” of corporate America’s indifference to its workers. Where you draw the line on these types of issues will be your own decision, but be aware that sloppiness can open the door to criticism.

■ Responsibility to Other Creators: Intellectual Property Rights

The digital age and the advent of the Internet have made literally billions of images, sounds, and moving image clips available at the push of a button. Documentary filmmakers, who are often talking about historical events or faraway places, often find themselves wanting to use material produced by others. The ethical aspect of this is clear. If you use someone else’s footage, music, or imagery, you need to get their agreement or compensate them in some way. This is a standard aspect of filmmaking. Typically, when you buy the right to use a still image, a piece of music, a sound effect, or a film clip in your work, you will have to sign a licensing agreement that spells out the specific ownership rights you are obtaining and what you are paying in return for those rights.

Copyright laws, which started in England in the 1700s, acknowledge the rights of the creator in any work. These laws vary from country to country. Currently in the United States, they protect a work for up to 75 years after the death of the author. The goal of copyright is to protect work long enough for the maker to profit from it. While the rights of the maker are acknowledged, they have to be seen in relation to other rights, broadly speaking the right to speak of and from a common culture.

Culture is a shared field, a common heritage that artists can draw on. Digital media and the Internet have contributed to the spread of remix culture, where creators can easily borrow and adapt images and sounds created by others. In addition, since the advent of the electronic age, big players in the entertainment industry have been working to protect their own interests by extending the reach of copyright law. This has brought the broader discussion of cultural production underlying intellectual property into new prominence. Documentary filmmakers can find themselves on conflicting sides of these debates. On the one hand, we rely on sales of our work to make back money spent on production and to support ourselves. On the other, we find ourselves increasingly burdened by expensive licensing fees for film clips, songs, and photographs. One alternative to clearing images is to use materials with Creative Commons licenses, which are more flexible and vary their permissions with the use to encourage sharing (Chapter 20).

Fair Use

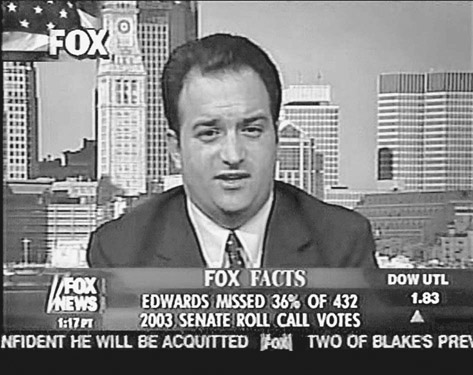

There is some flexibility in copyright law that can be of specific benefit to documentary filmmakers. Fair use is a doctrine written into law in some countries, including the United States, which allows creators to use copyrighted material in certain specific contexts (see Chapter 20 for a more complete discussion of fair use). One of the most important aspects of fair use is the idea that you can use copyrighted material if you are offering a social or political critique of the material. An example would be Robert Greenwald’s documentary Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism (2004). In order to support his claim that a pervasive right-wing bias and a lack of journalistic standards pervades Fox Network despite its claims to offer “fair and balanced” journalism, Greenwald made extensive use of Fox’s own broadcasts. He intercut the footage with interviews with former Fox News reporters, analysis of specific coverage, and a look at Fox’s position in the larger media sphere. In this case, the use of Fox’s broadcast material was firmly situated within a critique and was thus covered by fair use (Figure 5.5).

■ Figure 5.5 Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism uses images from Fox News, under “fair use” doctrine, to critique that network’s news handling practices.

Finally, there are no copyright issues when using material that is in the public domain. The public domain is the term for material that has aged out of copyright, was produced before copyright existed, or was produced for the public (typically material made by government agencies). For more information on where to find public domain images, see Chapter 20.

■ Conclusion

This chapter has offered a variety of very important concerns for filmmakers. Remember it is a guide, not a roadblock! In our experience, students may become overwhelmed or even paralyzed by the kind of questions we are raising in this chapter. The point of ethics is not to prevent you from doing things, but rather to help guide you toward a practice that is thoughtful, rich, and responsible to both your subjects and your audience.