Chapter 2

Documentary Styles

Once you have an idea and have completed basic research, it’s time to think about the stylistic approach you would like to take with your documentary. While it might seem at first glance that all documentaries use similar techniques, there is in fact a wide range of creative approaches documentary filmmakers use to represent the world around them. The elements of each documentary style—whether narration, interviews, archival footage, reenactments, or an on-screen filmmaker—are picked up or rejected by filmmakers for a variety of reasons. Some filmmakers use the same approach their entire careers, while others adapt their approach to fit the subject matter of each film.

Whichever style (or combination of styles) you choose, it is important to realize that the way you represent the world is as meaningful as the subject matter you choose. Your message to an audience is a combination of content and form. Being intentional about the choices you make when you film people, places, and events and edit them together is a critical part of being a documentary filmmaker.

It is impossible to understand documentary styles without a sense of the history of the documentary genre. Over the course of more than a century of documentary practice, people have adapted various moving image technologies (film, video, and digital media) to capture images of the real world and present them to audiences. At critical junctures, specific technological developments opened up new possibilities, changing the course of the documentary form. Equally important were the social contexts in which the films were made; as social trends brought new issues into focus, documentary filmmakers took up those issues. As governments, citizens, corporations, educators, and others realized the particular power of the documentary, they also contributed to the development of this body of work.

When you set out to make a documentary film, you are stepping into a tradition that spans from approximately 1895 to the present. It is important to know this history because you do not have to reinvent the wheel each time you make a film. Past filmmakers have struggled with issues of content, form, and ethics, and have created a legacy of stylistic approaches we can borrow from, adapt, and even oppose.

Because documentary films represent real people and situations, questions around their veracity, or truthfulness, have been part of their development since the beginning, and have actually contributed to the form itself. Here is a sampling of the questions that recur:

- Are documentaries “true”? How representative are they of the world they depict?

- What is included or excluded, and what are the implications of those choices?

- Did the presence of the camera impact what we see unfolding on the screen?

- Who is making the film? Funding it? What is their relationship to the issues or the world represented in the film?

- Who is speaking in the film, and for whom?

Some filmmakers see their work as an opportunity to converse with their peers about these questions, and about documentary itself. As filmmaker Lynne Sachs says:

I like it when the community I’m making the films about is interested in watching the film. I want it to be compelling and accessible to them, and for them to feel good about the way that their lives are represented on the screen. But I also want people who are really interested in cinema (and might not care about the issue at all) to look at my films and think that I’m doing something for the field that we’re in, that I’m taking this medium to a place it hasn’t been before.1

Whether or not you are interested in a conversation with other filmmakers about documentary form, understanding the possibilities and constraints of any given style will help you make critical choices about crew, equipment, and a host of other production decisions you will have to make before you even start shooting. A firm grasp of what is involved in each approach will also prove invaluable in editing, when you start to see the real possibilities of your footage, and to reconcile your ideas about what you were trying to make with what you actually have.

The following brief and very selective historical survey will give you a sense of the evolution of the documentary, and prompt you to think about questions of form, audience, and ethics as you begin to find your own place in the documentary tradition.

■ A Brief and Selective History of the Documentary

Many individuals contributed to the development of film technology in the late nineteenth century. Some, like Etienne-Jules Marey and Eadward Muybridge, were trying to slow down nature in order to observe it and better understand phenomena like animal motion (Figure 2.1). The development of the actual motion picture camera is attributed to Thomas Edison, working in New Jersey, and the brothers Louis and Auguste Lumière in France. Edison’s camera required electricity, and thus confined his mise-en-scène to a stage where he filmed circus performers, athletes, and staged productions. The Lumière camera, by contrast, was hand-cranked and portable, freeing a small army of operators to travel and document daily life in cities across the globe (Figure 2.2). In each location, the Lumière operators would film during the day, develop their film, and present it that same night for local audiences. Because of the Lumière camera’s mobility, and these operators’ interest in filming the world outside the studio, we locate the beginning of the documentary tradition in these 50-second films, which were called “actualities” at the time.

■ Figure 2.1 In 1888, doctor and physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey invented a method of producing a series of successive images of a moving body on one piece of film in order to be able to study its exact position in space through time, which he called “chronophotographie.”

Filmed with a stationary camera, on black-and-white film in one continuous take, the Lumière films are simple by today’s standards. But in a time when travel was out of most people’s reach, these films provided a glimpse of life in other countries and on other continents, and they satisfied a public curiosity about lives, customs, and cities not their own. Many contemporary documentary filmmakers pick up a camera and travel to other places, following the same impulse that pushed the Lumière camera operators across the globe to bring images home to audiences in Europe. While the issues involved in representing people of other races, classes, and cultures have been rigorously debated in the intervening century, the role of the documentary in sharing information and experiences across cultures remains an important part of its social role, and a common practice.

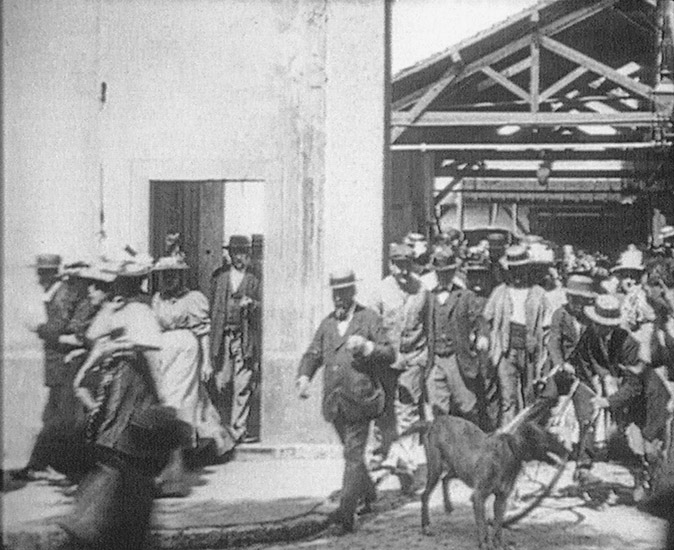

If turning a camera on other societies and foreign lands has been a constant in documentary, so has using the documentary camera to explore our own society. In the early Lumière film Workers Leaving the Factory (1895), we see a very early representation of “regular” people who are workers, not nobility or people with high social standing (Figure 2.3). To this day, those people or groups neglected by mainstream media, and marginalized more generally, are important documentary subject matter. The Lumière brothers were likely less interested in this than the generations that followed in their footsteps, but “giving voice to the voiceless” has been a justification for the documentary since its inception.

■ Figure 2.2 The Lumière cinématographe was a relatively portable hand-cranked camera. Its portability allowed operators to travel all over the world and document daily life. For this reason, the Lumière Brothers are considered by many to be the first documentary filmmakers.

The Lumière films also invite us to explore the question of documentary from the audience’s point of view. Why do people watch non-fiction films? What is the appeal? If we are going to make films for an audience, these are important things to consider. Georges Sadoul, in Histoire Générale du Cinéma, writes that audiences were less interested in the main action in scenes of people playing cards or feeding a baby (two early Lumière films) than in the details of leaves rustling in the background of the shot, or the dust from a brick wall being demolished.2 As editor and film theorist Dai Vaughn writes, “People were startled not so much by the phenomenon of the moving photograph, which its inventors had struggled long to achieve, as by the ability of this to portray spontaneities of which the theatre was not capable.”3

In his 1945 book The Theory of Film, Béla Balázs wrote about the particular power of documentary images (in this case footage of military battles):

This presentation of reality by means of motion pictures differs essentially from all other modes of presentation in that the reality being presented is not yet complete; it is itself still in the making while the presentation is being prepared . . . The cameraman is himself in the dangerous situation we see in this shot and it is by no means certain that he will survive the birth of his picture. It is this tangible being-present that gives the documentary the peculiar tension no other art can produce.4

This quality of “being-present” is not just a feature of war documentaries. It is a central aspect of the power of all documentaries. There is a spontaneity to events that unfold while you are filming that can serve your film well. Contemporary examples include Laura Poitras’ interview with whistleblower Edward Snowden in the Academy Award®-winning documentary CitizenFour (2014), where the presence of the camera itself in a Hong Kong hotel room is part of the drama because we know this man (and perhaps even Poitras) may be arrested for sharing confidential state department information.

■ Figure 2.3 A still from Workers Leaving the Factory (1895).

Impressionistic Filmmaking

Much as viewers of the first Lumière films were awed by the details of nature like leaves rustling, early documentary filmmakers were captivated by the ability of the camera to capture the poetry of everyday experience. Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens, in his film Regen (Rain, 1929), shows us what seems to be a passing shower in Amsterdam (Figure 2.4). The filming took four months, however, and the attention paid to each frame is clear in the film’s precision and beauty. Ivens’ filmmaking is referred to by historian Erik Barnouw as “painterly,”5 and by others as impressionistic. Whatever this style of filmmaking is called, it is characterized by an attention to the composition of the frame, including textures, movement, light, and shadows. This approach relies on metaphor, inference, and lyricism more than direct argumentation or human dramas.

In poetic documentaries, we can find breathtaking moments. A more lyrical approach can also strengthen the more literal points a film is making by inferring more than can be said in words, and conveying emotions as well as rational arguments. Filmmaker Fred Barney Taylor’s portrait of science fiction writer Samuel Delany, The Polymath (2008), uses a series of long elegant takes that emphasize patterns of light and the texture to evoke an imagined meeting between Delany’s grandfather and poet Hart Crane on the Brooklyn Bridge (Figure 2.5). The recreation of this poetic, timeless space for the viewer reinforces the film’s overall story by giving us a sense of Delany’s inspiration and imaginative abilities.

Handsworth Songs (1986), by John Akomfrah and the Black Audio Collective, uses the impressionistic style combined with more expository elements to create a nuanced and layered exploration of the uprisings in the Birmingham district of Handsworth in 1985. The film uses footage of protests and news coverage of the events of the sort used by many historical documentaries. It also, however, presents hidden narratives about racism and the black immigrant experience by layering fiction and poetry over archival images of West Indians arriving in England in the 1950s. Handsworth Songs was both celebrated for trying to create a new filmic language and attacked for failing to speak clearly enough to audiences, a tension that will always be a risk for those working in a more impressionistic mode.

■ Figure 2.4 Regen (Rain) takes an impressionistic approach to representing a passing rain shower in Amsterdam. Note the attention to the composition of the frame, and the pattern created by the light on the umbrellas.

Dziga Vertov and Reflexivity

Dziga Vertov, a Soviet filmmaker and founder of the Kino-Pravda (“film truth”) movement in the 1920s, was another pioneer of the documentary genre. Among many achievements, Vertov included the process of making the film within his films, a practice that later became known as reflexivity. In Man with a Movie Camera (1929), Vertov includes many shots of his cameraman, Mikhail Kaufman, climbing smokestacks and riding in moving cars with his camera, to demystify the filmmaking process by showing that films are made by actual people. At one point in the film, Vertov cuts from a shot of children to the same shot on actual film, in the editor’s hands. We then see Elizaveta Svilova, the editor, cutting the film with scissors and joining the shots together, and we watch the edited sequence. This sequence literally shows the audience how the film is constructed, frame by frame. Reflexivity was important to Vertov because the audiences for his films included a wide range of Russian citizens, many of them illiterate peasants who had likely never seen a film in their lives. Vertov was attempting to help audiences understand that what they were seeing is not reality, but a representation of it. This marked the beginning of a long tradition in documentary of demystifying the process behind the product, and encouraging audiences to retain a critical perspective as they watch.

■ Figure 2.5 The Polymath, a portrait of writer Samuel Delany, uses impressionistic visuals of New York City to give us a sense of Delany’s imaginative abilities.

Reflexive films take many forms and are among the most intellectually engaging in the documentary genre. This style reemerged with force in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, when a critique of authority and the rise of people’s movements established the importance of letting audiences know not just that the film is constructed, but who is constructing it, from what perspective, and to what end. A notable example is Rea Tajiri’s History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige (1991), about the internment of Japanese–Americans during the Second World War. The film uses clips from Hollywood movies and US government propaganda films to show how a nationalistic official perspective on the internment was constructed—even literally—by showing the film slate and call for “action” as internees are posed before the camera.

Tajiri uses a first-person narration, which lays bare her own subjectivity, as a driving force in the film. This is another common characteristic of reflexive films. She also uses interviews with relatives to excavate a suppressed history. In her narration, she says:

I began searching for a history, my own history, because I had known all along that the stories I had heard were not true, and parts had been left out. I remember having this feeling growing up that I was haunted by something, that I was living within a family full of ghosts. There was this place that they knew about. I had never been there, yet I had a memory for it.

History and Memory: For Ashiko and Takashige. Dir. Rea Tajiri. Women Make Movies, 1991. DVD

Her investigation reminds us that nothing can be taken at face value—that histories, like memories, are subjective and incomplete. The same is true of the documentary film.

The British Film Movement and the Expository Film

In the 1930s, documentary took a new turn, based on the need for some kind of forum for addressing social problems of the era, from global economic depression to the rise of fascism. Often when people think of a documentary, it is the expository documentary developed at this time they have in mind. In fact, the very term “documentary” was originally coined at this time by famed British filmmaker, theorist, and producer John Grierson. Grierson saw the huge potential for film to help create discussion of social issues on a national level. Inspired by the revolutionary films of Soviet makers including Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein, Grierson sought to infuse the documentary with the poetry of everyday life, a more realist approach that would elevate the form above the standard non-fiction fare of travelogues and newsreels:

[A] sense of social responsibility makes our realist documentary, a troubled and difficult art, and particularly in a time like ours. . . Realist documentary with its streets and cities and slums and markets and exchanges and factories, has given itself the job of making poetry where no poet has gone before it, and where no ends, sufficient for the purposes of art, are easily observed.6

One of the most well-known films of this era is Housing Problems (1935), directed by Arthur Elton and E.H. Anstey, who worked for Grierson at Great Britain’s Empire Marketing Board. While the film has drawn criticism for posing the poor as victims of circumstance who can be rescued by enlightened public policy, its innovative use of sync sound allowed slum dwellers to speak for themselves about their housing conditions on film for the first time (Figure 2.6). Sync sound also allowed the filmmakers to feature officials and experts, making it an early example of expository documentary. This style has persisted to the present day. In these films, you will find a belief in the value of a well-written voiceover, a mix of witness and expert testimony, footage shot in common locations of people engaged in everyday activities, and a willingness to use teaching tools such as maps and diagrams, all devoted to giving a viewer the tools for discussing and exploring important social issues.

Jay Rosenstein, a more contemporary practitioner of expository documentary, says:

With In Whose Honor? (1997) I knew much of the information in the film would be controversial to a fair number of people, and the first time they would be hearing it. I decided to couch it in a style of storytelling—the expository style—that maybe people would be more comfortable and familiar with. If the film had been more experimental, it wouldn’t have been as effective as political advocacy, which is really what it was.7

One of the key social values of documentary film is its ability to explore and convey complex problems facing society in an accessible way. In a world where the causes of social problems are complex, documentaries excel at revealing links and drawing connections that might not be readily visible to people. They also link the lives of regular people to the larger picture. The expository style is often chosen by documentary filmmakers who want their films to have broad social impact.

The expository style is also often used because it is efficient, and offers the possibility of delivering information in narration or text where it may not emerge organically from your footage. Rosenstein says:

I’m trying to impart a certain amount of factual information in my films. And you can usually explain something in narration much more efficiently and concisely than a character can. Also a lot of what is in the film happened before I started shooting, and I couldn’t see a way of making that film effectively in any other way.8

While the expository mode continues to be one of the most popular approaches, it does have dangers. Perhaps the strongest is the tendency for expository films to become illustrated lectures and therefore dryly didactic. One way to avoid this trap is to make use of strong visual evidence, images that convey the story you are trying to tell with little or no explanation (Chapter 7).

■ Figure 2.6 Housing Problems pioneered the use of interviews and expert testimony, hallmarks of the expository style.

In In Whose Honor?, Rosenstein develops a sequence that shows bumper stickers and signage of the Chief Illiniwek mascot on cars, homes, and stores (Figure 2.7). Even though nobody in the film speaks explicitly to this issue, the shots provide visual evidence that the power of the mascot extends far beyond the sports field, and that it won’t be easy to get people to let go of their allegiance to it. This visual evidence moves the discussion to less abstract, more emotional turf where human emotions and loyalties are central.

■ Figure 2.7 In Whose Honor? uses visual evidence to show you how prevalent images of Chief Illiniwek are in Champaign, Illinois.

TV Documentary as a Subgenre of the Expository Style

Television is such a major platform for non-fiction material that the type of documentary seen on TV has come to define the form in the popular imagination. While most TV documentaries fall into the expository category, it would be limiting to conflate the two. One way of understanding the difference is to think of the “news documentary” as a subgenre of the expository form. The news documentary, which has ancestors in both radio and television, tends toward an on-air host or reporter. At its worst, this kind of filmmaking takes a news radio-style script and illustrates it with highly literal visuals, rarely pausing for breath. At its best, it is more akin to investigative journalism. Examples of the latter type include the BBC’s Panorama or PBS’s Frontline, which are heavily researched and often break important stories that have not appeared in other media. They depend on multiple teams to cover events in different regions of the globe and build an authoritative case using strong, verifiable evidence. In addition, these programs often find characters whose personal involvement and concern can help humanize the issue at stake and avoid overtly didactic or “preachy” filmmaking.

Observational Filmmaking

One of the most influential developments in documentary style was the advent of cinéma vérité and direct cinema in the 1960s. These styles sprang from a desire by filmmakers in the early 1960s to get closer to reality with new portable technologies including lightweight 16mm cameras, zoom lenses, and portable tape recorders capable of capturing sync sound. While two major schools of observational filmmaking emerged, both are characterized by the use of small crews with lightweight handheld equipment, filming unscripted action with a highly observational “fly-on-the-wall” approach. The advantage of this method is that life as it unfolds can be very engaging, and filming it observationally puts viewers in the action in a way that no interview or voice-over commentary can do. Unlike the Lumière films, which were observational from a distance and used a static camera, these filmmakers put themselves and their cameras in the center of the action, filming from multiple perspectives and using continuity style editing to create a sense of a seamless reality (Chapter 19). Looking at a story that seems to “tell itself,” viewers can make up their own minds how to understand an issue or whether to believe a character. Albert Maysles, who with his brother David and others in the United States developed a style that came to be known as “direct cinema,” says:

On television they’d rather take a shortcut and have somebody tell you what happened. We had this revolutionary idea about how to make a documentary with no staging, no narration, no host, no music. Just let it happen, and be at the right place at the right time, and you’ll have a film.9

It is not surprising that this approach appeared at a moment when people were starting to question authority and where having someone tell you about the world had become less convincing than seeing it for yourself.

One drawback of a direct cinema approach is that you have to spend significant amounts of time in a situation to capture moments and images that are, in fact, revealing. These filmmakers spend days, weeks, or months on location filming. That closeness means a real chance to learn about the ins and outs of a situation, and to observe people changing as they confront the obstacles and challenges facing them. But it can also require extensive resources.

A critique of direct cinema is that it is overly naive about the possibility of capturing “the truth.” No camera is a “fly on the wall”, unseen to subjects. The presence of the camera and the fact that people know they are being recorded necessarily alter the course of the events being captured. People may ignore the camera, but how much their behavior changes because of its presence is open to debate. A classic example is An American Family (1972), a 12-hour PBS series produced by Craig Gilbert that was built around the daily drama of one American family, the Louds. This particular drama ended in a divorce, raising the question of whether the stresses of being on camera, and seen by millions, may have altered the reality being filmed. There is no way of knowing, but as a documentary filmmaker, you should always keep in mind that your presence is a factor in the situation you are documenting.

The influence of the filmmaking process asserts itself during the postproduction process as well. Fred Wiseman, the maker of films such as Titicut Follies (1967) (Figure 2.8) and High School (1968), says:

Say you’re at a place for four hundred hours and you shoot forty hours and you use nine hours. All that is selection, all that is choice. Sure. But really all I’m saying is that I try to make the selection based on my view of the experience as filtered through what I was before the film and what happens while I’m there. This means not only for the period of time that I was at the institution, but also sitting in front of the movieola trying to think through . . . what the experience meant to me.10

The cinéma vérité movement in France emerged when makers like Jean Rouch challenged the idea that the camera could capture reality, or life as it would have occurred if the camera wasn’t there. Rouch believed in the power of the filmmaker to catalyze events, and this school of a more participatory observational filmmaking came to be known as cinéma vérité. Erik Barnouw writes, “The direct cinema documentarist took his camera to a situation of tension and waited hopefully for a crisis; the Rouch version of cinéma vérité tried to precipitate one.”11

In Rouch films such as Chronique d’un Eté (Chronicle of a Summer, 1960) (Figure 2.9), made with Edgar Morin, we also find a reflexivity that has its roots in Vertov. We see the film’s participants discussing the shooting process with Rouch and Morin, and at the end of the film we see them watching themselves on the screen, and discussing how they feel about their representation. The film ends with Rouch and Morin discussing whether their film “experiment” has been a success.

■ Figure 2.8 Direct cinema films like Titicut Follies, about a Massachusetts psychiatric hospital, strive to capture life “on the fly,” as though the camera isn’t there.

■ Figure 2.9 Chronique d’un Eté (Chronicle of a Summer) is an example of Cinéma Vérité. In this scene, the filmmakers include a discussion about the filmmaking process with one of their main subjects.

While the debates between the practitioners of direct cinema and cinéma vérité might seem theoretical, there are practical applications to the arguments. When should you interfere in an observational situation, and when should you sit back and let it unfold? Julie Gustafson describes how, while filming Casting the First Stone (1991), a film about women on both sides of the abortion debate, not intervening was the right choice:

There is an incredible scene where Joan and her husband are having dinner, and she says, “You know, he didn’t want me to get arrested.” They had just served us lunch, and I had put the camera down, and very quietly got up and picked it up again. The soundman didn’t realize what I was doing, but I knew the wireless microphone was on her, and didn’t want to interrupt the conversation, because by then already the husband and wife were arguing, and I knew it was an incredible scene. And that’s where the documentary turns to drama. You don’t interrupt, you do whatever you can to get the scene.12

On another occasion, Gustafson decided to provoke a response, albeit subtly:

In the case of The Pursuit of Happiness (1983), which was about whether Americans do or do not pursue happiness, I was filming the main character doing the dishes. And after a while I asked her, from behind the camera, “What do you think happiness is?” She answered, but kept doing the dishes, and it became an interview but also turned back into a vérité scene. I have found this to be a very effective, very informal strategy.13

Another cautionary note for an observational filmmaker is that placing an audience inside a situation with limited contextualization can mean leaving out significant portions of the big picture. As documentary scholar Brian Winston suggests, it is easy to confuse access to an interesting situation for a film idea, skipping the need for background research to shape your hypothesis. This can result in a close-up view without much context.14

Restrepo (2010), the Oscar®-nominated 2010 documentary about the war in Afghanistan, took filmmakers Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger on 10 trips to the Korengal Valley with troops of the 173rd Airborne Brigade. While the film was highly and deservedly praised by critics, others have pointed out that a significant facet of the experience was essentially left out. There were no interviews with the Afghanis that the Americans, whose valiant efforts are so closely portrayed, were there to protect. Nor did the filmmakers include experts who might have offered an analysis instead of an easy identification with the US military. As journalist Nick Turse suggests, the result is a film that provides a limited point of view on the war, and offers the experience of combat as the whole of the geopolitics of war.15

From the Observational to a Reemergence of the Reflexive

The 1960s political movements—antiwar, Women’s Liberation, Black Power, and others— shook Americans’ belief in the official version of events presented, in expository form, by television news journalists. The development of portable 16mm film equipment that could record sync sound and the creation of a consumer video camera by Sony in 1967 introduced the possibility that communities could represent themselves. “People taking charge over their own lives was one of the battle cries of the late Sixties,” noted public access television pioneer George Stoney.16 Media representation was no exception. Documentaries had long focused on the plight of the less advantaged in society, and advocated for change, but now those communities wanted to take control over how they would be represented.

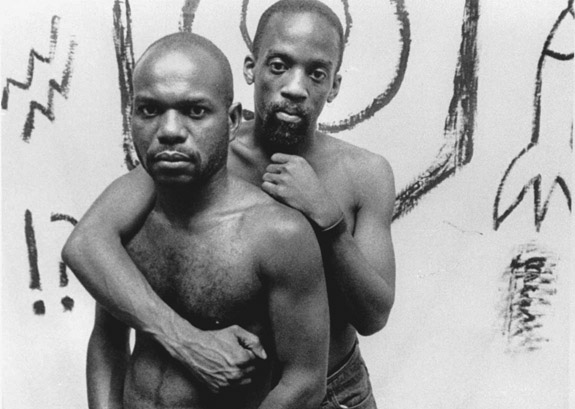

In the 1970s and 80s, this tendency toward self-representation was also fueled by identity politics, political movements based on the common experience and concerns of groups identified on the basis of gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or HIV status. The practices of these groups included consciousness-raising, celebrating the pride and integrity of marginalized groups, excavating ignored or suppressed histories, and focusing on personal experience. Many of these practices involved employing documentary film as a way to document process and influence majority opinions. More and more, individuals were making documentaries that spoke from an intensely personal, subjective position. Many of these films used narration, but they eschewed the “voice of god” omniscient narration of the expository film, and spoke in the first person instead.

A notable example of this kind of work is Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied (1989), about the experiences of black gay men. The film is intensely personal as well as reflexive. Unlike Vertov’s form of reflexivity, which deconstructed the filmmaking process, Tongues Untied goes further to take apart the idea that there is a fixed position from which we can speak. Riggs appears in the film, speaking to the camera. He tells us how he identifies with other gay men, but when he is subjected to racism within the gay community, he identifies as a black man. The film presents us with the idea that people’s identities are flexible and can coexist. Riggs’ film reminds us of the power of telling personal histories, and about how individual voices can be powerful representations of a collective (Figure 2.10).

■ Figure 2.10 Tongues Untied takes a highly subjective, personal approach to present audiences with a look at gay, black male identity.

Not all identity subgroups are based on ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender. They can also be geographic. In Stranger with a Camera (2000), Elizabeth Barret uses an essay documentary style to investigate the circum stances surrounding the 1967 death of Hugh O’Connor in Eastern Kentucky. O’Connor, a filmmaker from the National Film Board of Canada, was killed by a local man, Hobart Ison, after filming images of one of Ison’s tenants, a coal miner. Barret uses a narration written in the first person, foregrounding her identity as a filmmaker from the Appalachian region. In the film, she says:

These are the mountains I come from in Eastern Kentucky. The killing that happened here had a lasting effect on the lives of everyone who lived through it, and now that includes me. Over the years I learned what had happened, but I wanted to go beneath the surface, to find out why it happened. What brought these two men—Hobart Ison with his gun, and Hugh O’Connor with his camera—face to face in September of 1967? As someone who lives in the community that I document, what can I learn from this story, now that I have stood on both sides of the camera?

Stranger with a Camera. Dir. Elizabeth Barret. Appalshop, 2000. DVD

What follows is an unusually nuanced and deep exploration of the ethics of documentary representation. As someone with a foot in both the filmmaking world and the world of those represented in the many documentaries about Appalachia, Barret’s first person position gives her authority with the audience. The conflicted nature of her position—she is critical of the O’Connor murder, but also understands the historical pain this community has felt over its representation as an impoverished backwater—is the dramatic engine driving this film.

Reenactment in Documentary

Finally, there is the tricky ground of reenactment in documentary. For an art form that depends by definition on its close relationship with the real, reenactment can be a touchy subject. For many viewers, reenactment suggests actors pretending to be Roman Legionaries at Hadrian’s Wall, or patriotic Continental soldiers in Con cord, Massachusetts. Historically, stilted action and overly literal interpretations gave reenactment a mediocre reputation. It does, however, seem to be having a bit of a heyday as filmmakers explore the porous boundary between documentary and fiction forms.

■ Figure 2.11 In this scene from All My Babies, “Miss Mary” Coley and one of her clients reminisce. While the scene is staged for the camera, the participants are not actors, but the real subjects of the documentary.

One important area of reenactment in documentary, is that of people performing their own lives. This tradition goes back to the 1930s. A classic example is George Stoney’s All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story (1952). This portrait of Georgia midwife “Miss Mary” Coley is built around staged scenes where Coley, with some of the mothers whose children she helped deliver, recounts the story of her own career (Figure 2.11). This approach empowers people to be experts on the story of their own lives, and is likely to remain a useful tool for documentary.

The postmodern era has brought different approaches to reenactment. One of the most notable examples is Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988). The film is an investigation of the murder of a police officer, and the subsequent trial and conviction of suspect Randall Adams. There is one key witness, the partner of the murdered officer. But this officer’s testimony, even about her own location at the moment when her partner had approached a stopped vehicle on a dark Dallas highway, is in doubt. A key detail is a milkshake that has landed in a position that makes it unlikely that Officer Teresa Turko was where she said she was at the time of the shooting (Figure 2.12).

■ Figure 2.12 The flying milkshake becomes a key detail in the reenactment of the killing of a police officer in The Thin Blue Line.

Where was Turko when the shooting occurred? In the car? Out of the car? How many people were in the suspect vehicle? Two people? One person? What did the driver look like? Did he have bushy hair? Sandy-blonde hair? All of this is critical information in deciding who did it, who killed the cop.

How do you represent this in a movie? How do you evaluate the nature of competing and conflicting evidence? It is through reconstructing the past with reenactments.17

Here, the reenactments do not offer us reality, but differing versions of the facts from different witnesses, versions that change substantially during the course of the film. As Morris notes, his reenactments invite not the suspension of disbelief, but the opposite: the suspension of belief in the truth of the image.

■ Figure 2.13 Direct sun is used as a hard backlight and also bounced back onto the talent to provide a soft key (left). When subjects are in the shade (right), a reflector can bounce sunlight back onto the subject to get a better exposure and contrast range.

Another approach to reenactment is offered by films like Bianca Giaever and Rachel Antonoff’s short documentary Crush (2014). The film’s soundtrack is a straightforward account by Antonoff’s parents, of how they first met. The images offer a contemporary reenactment of a college romance in 1972 that develops as the account proceeds. In a cheerful comedic sendup of young love, the actors lip-synch the narrative while going from a dorm room to a pumpkin patch to a laundromat.

A more subtle approach is offered by filmmakers who seek to evoke the past through recreated situations, where the “enactment” is more one of memory. Sasha Wortzel, a graduate of Hunter College’s Integrated Media Arts MFA Program, made a short documentary Paint It Again (2011) that explored the home shared by a woman and her late partner of over 40 years. Now the home of only one surviving partner, the house is full of artifacts that hold memories and hint at a life shared in this space—a life that is now gone. A mix of quiet spaces and period music creates a sense of what is lost when a loved one dies.

■ Conclusion

With all these styles available—impressionistic, reflexive, expository, observational—it can be difficult to find your way. All of these approaches have advantages and drawbacks. Most filmmakers end up borrowing, mixing, and adapting strategies from multiple traditions. Also remember that the content of your film will, to a great extent, determine your documentary’s style.

Think about the story you are trying to explore. Can you follow it in real time and watch it unfold? If you can, then an observational approach could be appropriate. Are you involved in an area where policy discussions are central? Then interviews and a more expository approach may work for you. If you are taking on a story that is about your own history, or that you are connected to in a personal way, some reflexivity may be in order.

Finally, there is no way to grow as a documentary filmmaker without watching films. Think about the documentaries you admire and why they touch or speak to you. Look at how other makers structure their storytelling. Take advantage of what is available on the Internet, in libraries and universities, and screening in theaters, at festivals, and in community spaces near you. Seeing how others approach subjects and solve problems will enrich your own sense of what is possible.