Chapter 9

JOURNEY TO SHARED VALUE

The current model dictates that the needs of society not met by government or business are left to the charity or for-purpose sector, which does its best to fill the gaps. Most of its funding comes from individuals and the business sector. In his article ‘Australian Giving Trends — Recovery Confirmed, Evolution Gains Pace’ for JBWere (October 2013), John McLeod notes that 86 per cent of the giving (excluding donations to private ancillary funds) was by individuals.

In addition to demonstrating the importance to charities of individual donors, this finding also highlights the opportunity for business and government to increase their participation in the sector. If the combined contribution to the for-purpose sector by government and business sits at 14 per cent, the obvious question is why is it so low?

Changing the operating model

It might be argued that it is not the responsibility of business to fill the shortfall, that they are already doing their bit by employing those who make the contributions and by paying their taxes along the way. But what if the operating model changed so it was made more attractive to business to engage? What if it was less about giving and more about partnering that saw returns flow to them through increased revenue, a more engaged workforce and the opening of new markets to do business in?

The current model of donating funds for what can be very little return to the business is limiting. There are of course plenty of areas of return to business from their engagement with the for-purpose sector, including employee engagement, new markets, staff retention, brand enhancement and many others, as covered in chapter 3.

Under the current model the revenue needed to meet social needs can be increased only by the greater generosity of those who give or by expanding the numbers of those who give. As Dan Pallotta notes, giving in the US has remained at around 2 per cent for the past 40 years. The reports of giving in Australia are a little more encouraging, at around 5 per cent. The problem with running campaigns to encourage those who already give to give more or enticing new people into the sector, no matter how successful they might be, is that they too are limiting. This is not to say that we should abandon our efforts to encourage donors. John McLeod's JBWere report shows hopeful trends in the Australian market. The past 15 years have seen a 5 per cent increase in the number of taxpayers claiming a deduction for donations to charity, rising to 38 per cent. The amount that people are donating on a per annum basis has also grown by 6.6 per cent over the past 10 years, outstripping the CPI, which has risen at 2.9 per cent over the same period. Our most generous donors are those of more mature age, with the age group being the first to pass $500 per person in annual contribution.

This growth in giving is certainly promising, but the analysis by JBWere also indicates that it is influenced by the strength of the economy and consumer confidence. Economic uncertainly triggers a drop in both the level of giving and the numbers of people who give. When people become more conservative in their spending because of uncertainty in the market, or when job security is threatened, donations to charities will be influenced negatively. The cost of purchasing the ‘feel good’ feeling becomes too high and there is less to go around. The knock-on effect of this is that as people lose their jobs, or fear their loss, as a result of a poorly performing economy, demand for the services offered by the for-purpose sector rises.

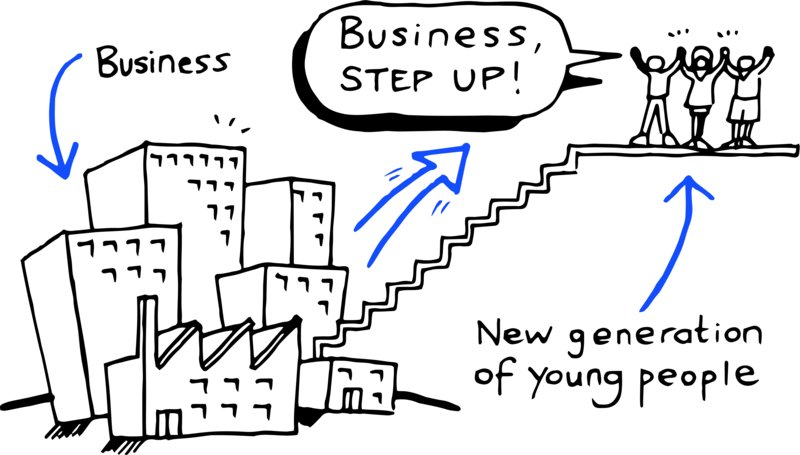

But as Michael Porter, Professor at Harvard Business School and co-author of Creating Shared Value, puts it, ‘There is a reason to be optimistic about the future’, and that optimism rests in considering how else business can contribute to addressing the problems that society faces other than by creating profits. The old paradigm was that business paid their taxes and employed people, and that was how they contributed to the needs of society. Profit, says Porter, ‘was seen as taking away from society, but it is that very profit that enables us to solve the problems of society’. He adds, ‘Businesses acting as businesses, not as charitable donors, are the most powerful force for addressing the pressing issues we face. The moment for a new conception of capitalism is now; society's needs are large and growing, while customers, employees, and a new generation of young people are asking business to step up’.

It is the profits that companies are able to generate that offer the scale to take on the challenges in the community that previously have been left to the well-meaning but poorly funded and not always efficient not-for-profit sector. As we have seen, it is access to resources that often defines the scale and scope of their projects.

The proponents of shared value suggest there are three ways in which it is created:

- by reconceiving products and markets

- by redefining productivity in the value chain

- by building supportive industry clusters at the company's locations.

Corporate social engagement is a broad term that seeks to capture the various ways in which business engages with the community other than through the commercial relationship between producers and consumers of goods and services. Businesses with an active CSR program, those who act as good corporate citizens through engaging in corporate philanthropy, and ‘green’ companies all lay claim to ‘contributing’ or ‘giving back’ to society.

The thought leaders in this space are now looking to a realignment: rather than sharing their profits, they seek to increase their profits by participating in tackling some of the more intractable problems of society, hitherto the domain of the for-purpose sector and offering little commercial return.

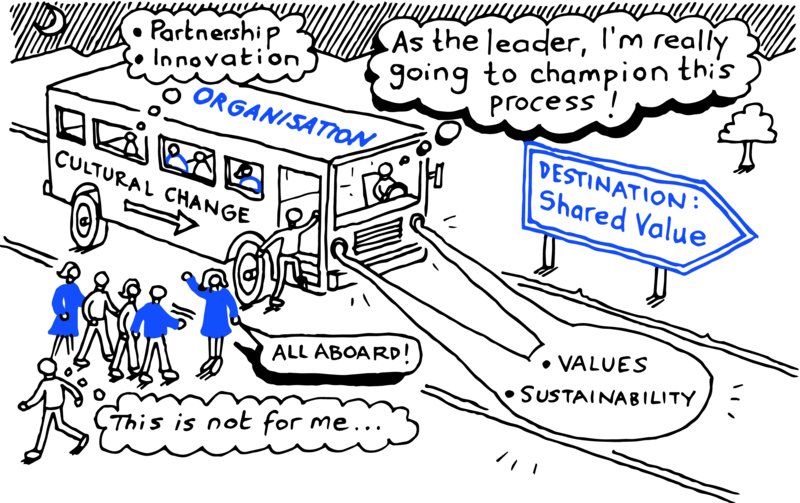

The path from zero to hero — from the company that makes no attempt to contribute to the community to one that uses a fully integrated shared value model — is as challenging and rewarding as one might imagine. A fundamental shift is required by business leaders looking to hitch their wagon to the shared value model. There will undoubtedly be scepticism and resistance, but as Seth Godin says, ‘If you're not upsetting people, then you're not bringing about change’.

Winning companies contribute

When asked for his views on corporate social responsibility, Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric from 1981 to 1999, commented, ‘I think a company's social responsibility is first and foremost to win … because winning companies are the only companies that can give back’. This is exactly the shift in perspective manifested by those companies who are embracing the concept of doing good by doing good. In those leading the way in this area, ‘giving back’ is not just an adjunct to the core business; it is the core business.

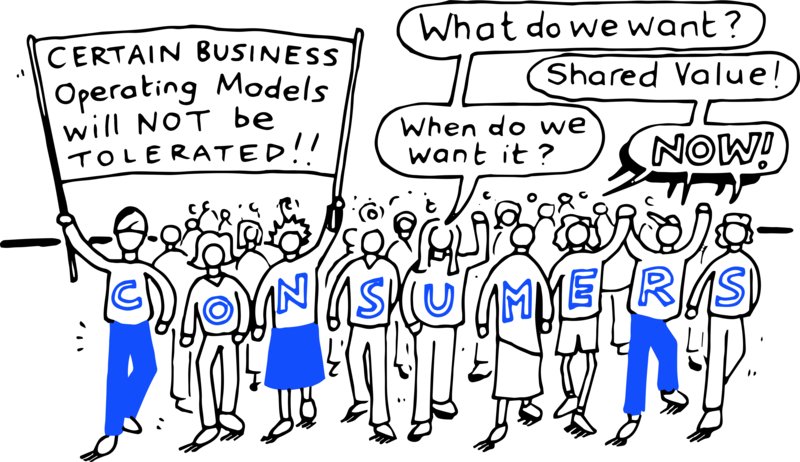

If we were to pursue the line of thinking encapsulated by Jack Welch, should we abandon the principles of CSR, shared value and corporate philanthropy and channel all of those resources into making more money as a business so that at the end of the day we have more resources to contribute to social needs? One problem with that philosophy is that consumers are no longer happy just to watch business making money without regard to the communities in which they operate. Consumers have made it abundantly clear that the business operating models of yesteryear will not be tolerated. Business practices that are harmful to the environment, exploit children as low-paid workers or deny benefits or a living wage to workers are no longer acceptable, and business knows that. Impact investment sees investors choosing what companies they want to be aligned with, which generally does not include socially harmful industries such as the tobacco industry. Companies who choose to ignore the community's expectations of what a good corporate citizen looks like do so at their peril.

Business also knows there is money to be made in conducting their business in a way that meets with customer approval. Rather than carelessly exploiting the communities in which they operate, they recognise the need to take a long-term sustainable view. The mining industry has seen the benefits in rehabilitating land and communities after their extraction operations have ceased. By focusing on measuring, reporting and improving on their social impact, business has a new reason to speak with employees and customers alike. They can speak proudly of how well they have done as a business, but also of the community benefits they have bequeathed.

Shared value requires change

A business's adoption of the concept of shared value seldom comes about by accident. For an existing business a period of time is needed to allow for the necessary transformational change. For most organisations, embracing the concept of doing good by doing good will involve a significant change to the modus operandi. Leaders of companies open to the opportunities that present by shifting the focus of their business are often daunted by the very real challenges, particularly when the company is profitable and the change proposed is significant. Jack Welch's advice? ‘Change before you have to.’

Part of the challenge is in the change in mindset that sees the needs of society shift from the periphery towards the core of the business. Redefining the business is by no means an easy or quick turnaround.

All the companies discussed in this book, large and small, have implemented change based on their desire to contribute to society. The global corporate Unilever has transformed its operations to reflect its social values; the small PR agency WordStorm determined to contribute its skills within the for-purpose sector; the Jellis Craig Group in Victoria boasts strong levels of engagement and increased consumer confidence as a result of its CSR initiatives. Large or small, all of the companies have seen the opportunities and taken on the challenge of changing what they do and how they do it to become leaders in their respective markets. Each has demonstrated a willingness to shift its position and take steps — some small, some groundbreaking — towards a model of shared value. And each has a leadership team in place that is willing to take up the challenge and embrace innovative ways to be a part of the movement.

The idea here is not that shared value is the only solution for companies looking to engage with the community. As proposed by Michael Porter and Mark Kramer in Creating Shared Value, shared value describes a miscellany of ideas and processes that have existed in the sector for a decade or more. The central proposition is that business can benefit commercially from tackling society's problems. For many companies starting out on the path of deepening their engagement strategy with the community, the journey to shared value may seem too daunting. For some starting out the idea of making a donation to a charity partner is seen as positively progressive when compared with what they are currently doing. Shared value is a journey, and the time it takes will depend on the vision of the leaders, their tolerance for risk, their ability to lead change and the commitment they and the board have to see shared value as part of their DNA.

Some companies and entrepreneurs have a talent for identifying an innovative social venture opportunity or position in the market and will target their business accordingly. A standout example referred to throughout this book is Blake Mycoskie's TOMS, a company that was formed to address a specific social need. In doing so Mycoskie created both a successful social venture and a very profitable business. While unique companies like TOMS will continue to appear when social entrepreneur meets social need, the bulk of change will come from companies, large and small, as they travel on their values-based journeys. It may be driven by opportunities for new business, to reduce operating costs or to enter new markets, or by the desire to improve their social presence. Whatever the trigger, engaging with the community sector can and should be good for business.

The CSR participation continuum

Most companies with employee numbers reaching into the thousands will have some sort of CSR platform within their organisation. It might be as simple as workplace giving, matching employee contributions or the allocation of time to staff to volunteer once a year with their favourite charity. It would be most unusual for a large company not to have in place some sort of program, no matter how simple. Small to medium-sized companies are more likely to have no formal CSR program in place.

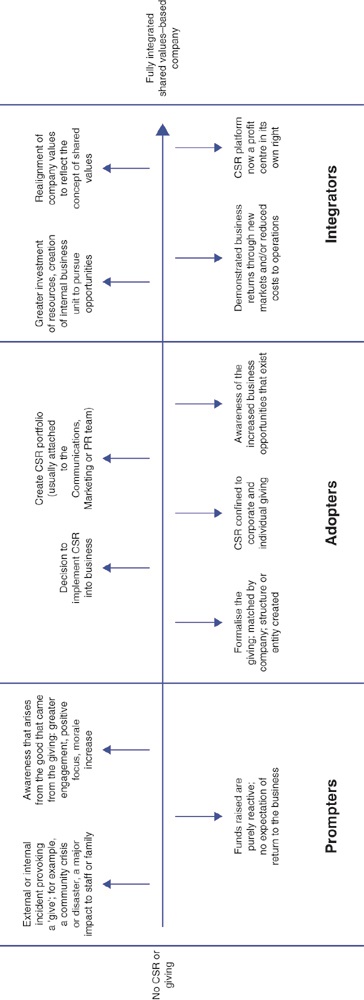

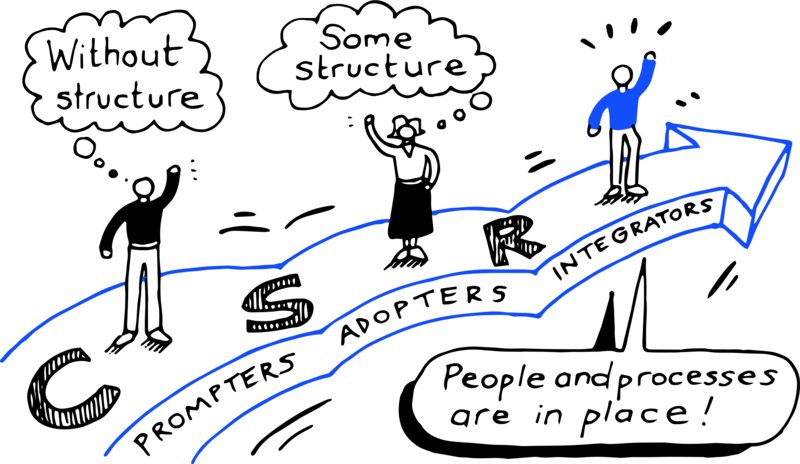

Figure 9.1 (overleaf) shows the various stages on the CSR participation continuum, from entering the space for the first time to assuming a fully integrated shared value model. The journey has three main phases, Prompters, Adopters and Integrators, each of which represents both influential individuals and processes that trigger change.

Figure 9.1 the CSR continuum — from entry to fully integrated shared value model

Prompters

These are the events and influential individuals likely to trigger the business to take action. Perhaps an internal or external incident calls for some sort of company response. Often this will be when an employee or a family member experiences a significant crisis or tragedy, such as through illness or accident, and those around them rally together to offer support. Another prompter might be a natural disaster on a local, national or international level.

Often the giving at such times will be based on an emotional response without form or structure, with someone within the company standing up to take the lead, for example in organising fundraising events. The response serves to unite staff across the company behind a shared purpose, bringing together those who previously might not have had reason to interact. With a shared focus, staff will start to engage with their suppliers and/or consumers on a different level as they encourage them to join in the endeavour, which creates an awareness of the power of engagement. These are the early signs of the returns that a structured CSR program can offer a company, and it's not long before it is recognised that the giving has been good for the business. Unless action is taken at this point, however, the momentum can be lost and the emotion that was driving the initiative passes.

The work done by the Prompters in these initial periods is normally outside their usual commitments. There will be a tolerance from within their business team and their family as they divert their efforts into what all agree is a worthy cause, but if the business is not set up for the sudden reallocation of resources, this tolerance by others in the organisation who must ‘pick up the slack’ will probably last no longer than the emotion driving the event.

Adopters

Adopters are those within the organisation who take action to see that some structure is brought to the process. They will act either through a desire for the giving to continue, which may be attributable to their proximity to the cause, or because they have identified the benefits to the business.

After the initial flow of giving from employees and the company, there is a realisation that for the giving to continue resources will need to be committed, and the company may consider establishing a legal entity to that end. During these early days the contribution will normally be financial contributions by the employees and/or the company. As the giving continues, the leadership team will look to find a ‘home’ for this new business project, and it will often become an extension of the work of the marketing, communications or PR team.

For those businesses who adopt a CSR initiative on the back of an external or internal tragedy, over time the initial enthusiasm will naturally cool. The national or international crisis may have dominated the media news, but who keeps the story alive within the business when the TV crews pack up and head on to the next news grab? Who within the business can talk to the change their donation has helped make, or why it is essential that the giving goes on? Perhaps someone else in the company is beset by tragedy — who decides which cause should be supported? How do you say yes to one and no to an equally worthwhile applicant? It is these sorts of challenges that will often persuade the company to shift their focus from a ‘cause-related’ strategy to a more holistic, values-based position. This is when the company will look to establishing their guiding principles, as outlined in chapter 12. The business has felt the power of engagement, and once experienced this is not something that many will choose to give up.

Integrators

These are the people and processes that are put in place to ensure that the benefits to the business of doing good by doing good are realised and embedded. As the maturity of the CSR initiative increases, so too will the allocation of resources. Separate business units will be established to identify new opportunities, undertake research and outline the scope of those opportunities. Increased funding will be allocated to those initiatives that bring measurable returns on the investment over the longer term.

The journey along the continuum towards shared value will see the business incorporate new values to reflect the importance of the new position. Those companies furthest along the continuum towards a true social venture entity will see their work addressing society's challenges in a profitable way as one, if not the, reason for their very existence. Are they making a profit in order to tackle some of the community's biggest challenges, or are they incidentally providing an answer to these questions while running a for-profit company? The distinction is blurred in the fully integrated shared value model.

We must accept, of course, that many companies either have no desire to pursue this path or are committed to taking much smaller steps while ensuring they maximise the return on their give. The shared value model as exemplified by Unilever Global or TOMS doesn't have to be embraced for smaller companies to see their CSR strategy becoming a profit centre in its own right. With the right measures, alignment to the values of the business and vertical support through the org chart, there is no reason why all businesses shouldn't be doing good by doing good.

Shared value and innovation

We can call it shared value, blended value, conscious capitalism or a combination thereof. The name is less important than the opportunities that changing the CSR mindset from one of corporate philanthropy to one of engagement for mutual benefit can deliver. When companies embrace the opportunity to tackle social problems that have gone unanswered or have been subject to no more than bandaid solutions, innovation can lead the way.

The corporate giant GE has coined the term ecomagination: ‘GE's business strategy to create new value for customers, investors and society by helping to solve energy, efficiency and water challenges. It is our belief that, through a constant commitment to innovation, we can design and deliver great economics as well as great environmental performance’.

Ecomagination, as characterised by GE, sits nicely within the definition of shared value. The concept as put forward by Porter and Kramer includes the broader supply chain and the building of local clusters, but the end result is the same — business deriving a commercial benefit from meeting society's needs.

The returns that GE attributes to its ecomagination business strategy are staggering and a testament to the value of bringing innovation to these opportunities:

R&D

Ecomagination commenced in 2005 and since that time GE has invested $12 billion in research and development. For the five-year period from 2010 to 2015 its commitment to R&D is $10 billion in the development of technology that benefits both its customers and the environment.

Products

Since the launch of ecomagination more than $160 billion has been realised in revenues. For the period of 2010–15, ecomagination is set to be a larger part of GE's sales with the company committing to growing ecomagination revenues at double the rate of its total company revenue.

Energy/GHG

Since 2004 GE has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 32 per cent against the 2004 baseline. In 2010 GE reported an 18 per cent reduction in its energy consumption from the 2004 baseline which it attributes in part to its focus on improved energy efficiencies that have been implemented in the company.

Water

The amount of freshwater used by GE in its operations has reduced by 45 per cent against the 2006 baseline. The savings in energy and water alone have realised a $300 million cost reduction.

Keep public informed

GE has a commitment towards communication and transparency. The production of its annual ‘Global Impact Report’ and consultation with stakeholders across borders, allows it to spotlight and develop the best ideas on the creation and use of power.

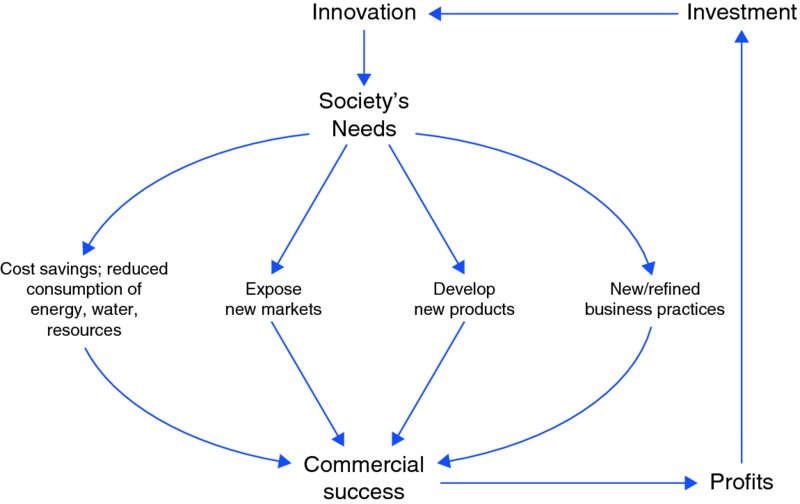

GE's experience is that each dollar it invests in R&D in line with its ecomagination business strategy will produce $10 in new revenue. Figure 9.2 (overleaf) illustrates some common returns.

Figure 9.2 the path from innovation to commercial success to reinvestment in innovation for tackling social needs

A focus on integrating CSR or shared value across the entire business when leading with innovation can reasonably prompt:

- reduced consumption and spend on resources such as power, water and waste

- the emergence of new markets that under previous models were seen as unprofitable

- the development of new products that might be at a lower cost entry point

- a change in operations or business practices that brings greater efficiencies.

In addition to their role as innovators, companies embracing the concept of shared value are redefining who they are. Nestlé is a leader in this area for the work it has done in repositioning itself with regard to the supply chain and building clusters for manufacturing. Michael Porter sees the change from its traditional positioning as a ‘food and beverage company’ to a ‘nutrition, health and wellness company’ as reflecting a change in how it views itself, the products it is offering and the way its customers see it.

Companies embracing shared value are, as part of that process, questioning what they do and what they stand for. The definition then starts to reflect the community needs they are meeting, as opposed to the products they are producing. Nestlé is addressing some of society's biggest challenges around health care by changing its offerings and changing what it is about.

The critics of shared value

The opportunity to create economic value through creating societal value will be one of the most powerful forces driving growth in the global economy.

— Michael Porter

The critics of the concept of shared value suggest, among other things, that the concept offers nothing new. Is there a huge difference between conscious capitalism, as already discussed, and the concept of blended value, as developed in the work of Jed Emerson? Do these simply offer an expanded view of CSR beyond corporate philanthropy?

Critics of Porter and Kramer's Creating Shared Value argue that their view of CSR is too narrow and doesn't reflect the broad approach that can be adopted, and that adopting this narrow view widens the gap between CSR and shared value. The criticism is not of the principles or concepts behind shared value, but of Porter and Kramer's grand claims about the radical shift it offers to the business world and the future of capitalism. This becomes a debate over semantics. If we agree there are benefits for the business community and society at large, then I suggest we embrace those parts that resonate and reject those that don't.