Chapter 11

VALUE OF SHARED EXPERIENCES

In chapter 2 we looked at the various ways in which both corporates and individuals can engage in the for-purpose space. We considered the worth of building a strategic plan around this investment and the value of creating an experience as opposed to making a cash donation.

In this chapter I'll spend more time considering the value of engineering shared experiences. I want to look at the value of these experiences from the perspective of the community group with reference to the work of three particular charities. I firmly believe that if a charity gets the experience right, they need have no worries about sourcing the next dollar. The value for the business partner is that the very experience in which they are participating to create value for their charity partner may be the best engagement tool they ever use.

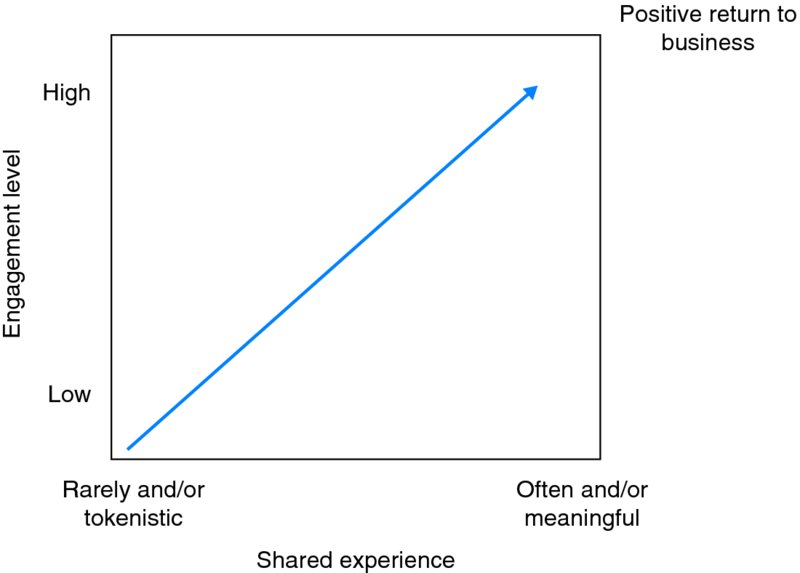

The model illustrated in figure 11.1 is not confined to building successful partnerships between business and charity. It may equally be applied to our personal relationships or to building stronger teams. If we engineer shared experiences, which is a fundamental role of business leaders, partners and parents, we are likely to build more successful relationships. Who has teenage boys who spend more time interacting on Xbox Live with other players they are likely never to meet, or teenage girls who spend more time on Facebook, Snapchat or whatever the next social network might be, than sitting around the dinner table having meaningful conversations with their own family? What modern family today wouldn't benefit from more shared experiences?

Figure 11.1 increased engagement = increased returns to your business

If we want to build stronger teams within our organisations, we must get out of the conference room and engineer shared experiences. Too much time and money is spent on the logic behind engagement. The richer and the more meaningful those experiences are, the more likely they are to bring results. Whether it be successful sporting teams or groups who have faced extreme adversity, it is the shared experience that unites them. In my earlier career as a forensic investigator I learned much about crisis situations. The experiences I shared in this challenging work created bonds between team members that, unless you were part of them, you could not understand.

The three charities profiled here — Hands Across the Water, OzHarvest and the Humpty Dumpty Foundation — operate in very different areas and support very different communities, but each relies on shared experiences as part of its success. Naturally the first of them is the one that is closest to my heart.

Hands Across the Water

I established Hands Across the Water after working as a forensic investigator in Thailand following the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, where I led national and international forensic teams in the identification of the thousands of poor souls who lost their lives in the tragedy. During my time in Thailand I was introduced to a number of children who had lost their homes, their parents and, in many cases, their extended family too. When I met the children they were all living in a tent, but not as some temporary stopgap — it was their home. After meeting these kids I made a commitment to do something to change their environment as best I could.

In the beginning I did what most charities do. You use whatever means you have to raise money. You have a goal, you talk about that and ask people to buy into your dream and give you money. That's usually pretty much where the value exchange begins and ends. I was fortunate that in the early days I had a unique platform from which to promote the charity, albeit in a very soft-sell kind of way. After leading the Australian and international teams in Thailand, and having performed a similar role in Bali after the bombings, I was invited onto the corporate speaking circuit to share my stories on leadership, among other topics. I would go on to work for Interpol in the counterterrorism space, spend time with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and also deploy into Saudi Arabia and Japan when disasters hit those countries.

These experiences led me on a journey around the world, sharing the lessons learned from working in these areas and building teams. Each time I spoke at a conference I would also share the stories of building Hands and the challenges in doing so. The more I spoke, the bigger Hands became; and the bigger Hands became, the more I spoke. The knock-on effect was that Hands was able to start assisting many more children than those that first came to us following the tsunami. We would go on to operate across the breadth of Thailand in seven remote locations, caring for children who had lost their parents, children with HIV and girls rescued from the sex trafficking industry.

But as Hands grew — and it grew quite quickly — I began to reflect on our success in growing at the rate we were in such a competitive space. What became clear to me was the value we were offering our supporters. It wasn't the timeliness of our communication or the glossy thank-you packages after a donation; it happened on a more meaningful and personal level for them.

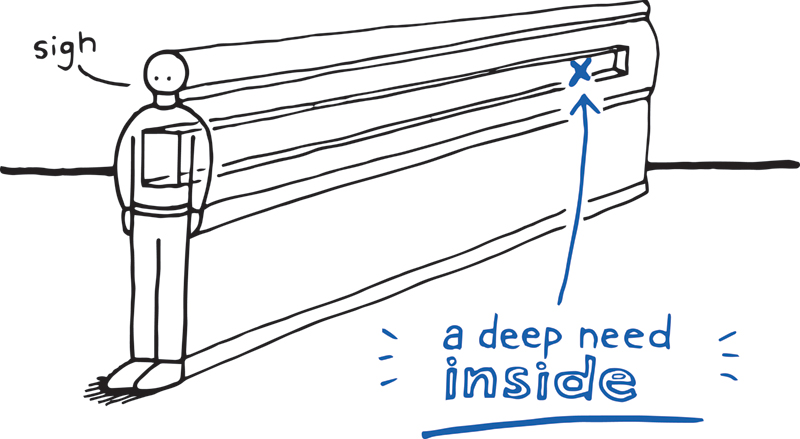

What we had stumbled across was the power of creating shared experiences, the concept I now know as creating shared value, which Simon Sinek identifies as meeting a personal need within the supporter.

Sinek talks about why people and companies are successful, and the importance of getting clear on that. He looks at what it was that drove 250 000 people to come together in one place, Washington DC, in 1963, to hear one man speak. The man, Dr Martin Luther King Jr., brought people together without an invitation, without a group text message or a Facebook invite. Sinek challenges the thought that they came together to hear Dr King speak; he suggests they came because to do so met a need within themselves. They came because of what it was giving them as individuals and the need it was meeting.

And this is what Hands stumbled across several years ago; it's why we are successful and why I believe we are about ‘providing meaningful experiences’. We are creating opportunities for our supporters to share experiences and along their journey to meet a need deep inside themselves. Some will acknowledge this, some won't, and some won't even realise that's what's occurring. It took me almost eight years of running Hands to realise what we are really about. Sure, we are bringing change to the lives of children. I know that, but for our efforts, many of the children in our HIV home would not be alive today. They had been dying every month, sometimes every week. After we took up responsibility for those children, there were no more deaths. Many of them were cured of AIDS; they still have HIV of course, but they no longer have AIDS.

The shared experiences that we have engineered here at Hands are best illustrated by the bike rides that we lead in Thailand. It's important to know the story behind them to appreciate where we sit today and the real value in creating experiences to build engagement.

In late 2008 the idea of riding from Bangkok to Khao Lak, a distance of 800 kilometres, over eight days, was floated past me almost as a throwaway line. But I was tempted, and soon there were two of us, each committed to raising $10 000 in sponsorship. At the time neither of us was a bike rider or even owned a bike. We left in January 2009 with 17 riders, and the Hands rides were underway.

Returning after that first ride with aches and pains from which I felt I might never recover, it took a little time before I began wrestling with the idea of repeating the experience. In 2010 we headed off for a second time with 34 riders, a number of whom were returning for the second time.

By then the interest in the following year's ride was such that I felt we needed to create two rides rather than keep expanding the numbers, so we didn't detract from the nature of the shared experience. In January 2011 we would leave Bangkok and ride with one group covering the 800 km course. Two days after completion I returned to Bangkok and joined the second group to ride another 800 kilometres.

The momentum continued to increase and in 2012 we changed it up a little. We started the first ride in early January, riding from Nong Khai in the far north-east of Thailand, down the Mekong River for eight days before finishing at our HIV centre, Home Hug, in Yasothon. Two days later we picked up another group and rode from Bangkok to Khao Lak.

In 2012 we had 59 riders across both rides, each raising $10 000 as well as paying for all their own expenses. After the 2012 ride we saw huge growth in participants, money raised and, very interestingly, a number of return riders. In 2013 on our northern ride 79 per cent of riders had ridden with us at least once before; some were back for their second or third ride, and some had never missed a year riding with us.

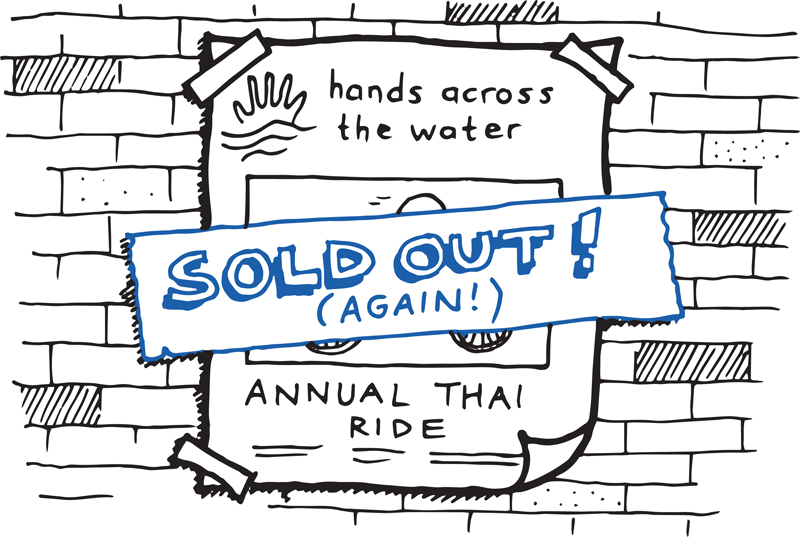

When we opened the registration list in 2012 for the 2013 ride, the places sold out in three weeks. We had never before sold out a ride and here we had done it in just three weeks. I wondered if we would match this extraordinary success when we opened registration for the 2014 rides on 1 March 2013. We not only matched it — we sold out in three days!

We were now raising well over three-quarters of a million dollars from our bike rides and were selling out in a matter of days. But something interesting started to happen. Instead of people asking for a spot on the ride for themselves or their colleagues, organisations were asking for an entire ride for themselves. They were looking for us to add new rides to our calendar, but they wanted them to be ‘closed’ rides just for themselves.

Our first closed ride was in 2013 with Family Business Australia, a national body supporting family business and the owners of those businesses. In February 2014 we held our second closed ride for a group of small-business owners and entrepreneurs, who had 30 riders on a cut-down version of the ride over five days, covering 500 kilometres, each raising $5000.

The riding calendar of 2014–15 is set to be our busiest yet with seven rides, five of which will be closed or private rides. We will see over 275 riders partake in one of our bike rides and we expect to raise over $2.5 million in the six-month period we have people on the road.

So is the rate of selling out the rides continuing to rise or have we topped out? On 1 March 2014, when the 2015 rides were opened, we sold out two rides in 90 minutes, and by the close of the first day we had 136 riders (from a maximum of 150) who would ride with us across three rides. Each of these riders is committed to raising a minimum $10 000 and paying for all their own expenses; 26 of the riders have committed to riding 1600 kilometres, meaning they have to raise $20 000 and take close to a month off work for the privilege of doing so. Equally staggering, 52 per cent of the riders in January alone are return riders.

In the space of five years we went from 17 riders, five of whom were members of my own family, and raising $173 000, to 250 riders raising $2.5 million. How to explain such phenomenal growth?

It's because of the shared experience. It comes back to what Simon Sinek says: each of the riders is doing it for themselves. That may be a little contentious and it may even offend some first-time riders who believe they are only doing it for the kids in Thailand.

A number of things make the experience so engaging. It's not just the achievement of raising $10 000. It's not the accomplishment of safely navigating your bike 800 kilometres through the heat and challenges on the road, and it's not just arriving at the home of the children who we have been raising money for. It's the totality of the experience and sharing something so amazing with others. Some of their fellow riders they will know already, some they will not, but often the riders return home with lifelong friends. That's the value of a shared experience.

So what are the five keys to the success of the rides and indeed of Hands itself?

- We provide a meaningful experience for supporters looking to engage on a level beyond simply donating a sum of money. Every supporter who participates in a ride will have engaged on average 100 people whose level of interaction will be limited to the donation of money. Our growth can be attributed in part to the experience of each rider, which then becomes their story, and many of those 100 people who previously only donated money are converted from passive donors to active supporters.

- The meaningful experience is one that is shared with others of a similar mindset. Seth Godin, in his book Tribes, articulates the human characteristic of wanting to be part of a group that shares a connection, passion and often a common leader: a tribe. Godin believes that tribes are behind every successful brand, organisation, politician, non-profit and cause. And yet, he laments, it can seem almost impossible to attract a tribe. The tribe we at Hands build is one that legitimises the desire of all grown adults to dress in Lycra and hang out with others of like mind, or have I got that confused with my personal desire?

- We provide an opportunity for people to step into an arena that is foreign to them. We have supporters who are already avid riders before coming to Hands, but the level of fundraising we require is new. Similarly, we have people who have supported charity before but have never considered riding 800 kilometres. One or other aspect of the ride is likely to be new to them — unless of course they are return riders.

- We are able to welcome the riders or supporters into the homes and lives of those whom they have supported, and this is a powerful experience. To see the difference they have made, the tangible results of their efforts, satisfies the ‘but for’ test.

- On a deeper level, Hands offers those who choose to support our work a high degree of confidence in what we are doing and where their money is going.

OzHarvest

Another charity offering meaningful experiences is Sydney-based OzHarvest, founded by the lovely Ronni Kahn to capitalise on an opportunity where the need was easy to identify. With a professional background in events management, running events of all sizes for corporate clients, Ronni was ideally situated to see the potential. A feature common to all the events she managed was food. The bigger the budget, the bigger the spend on catering — and often the bigger the waste of food at the end of the night.

Ronni thought there had to be a way to bring this abundance of untouched food to those who went without. But unlike many who experience a light bulb moment, she didn't bring together a group of mates and launch the next day; she did her due diligence. Not wanting to risk duplicating what others of the 600 000 NFPs in Australia were doing, she researched the need, options and who she could partner with. No one in Australia, as far as she could discover, was operating a model similar to the one she had in her head. What she did find was an organisation doing similar things in the US, so that's where she headed next. She was determined to learn from those who were doing what she wanted to do, to discover what she could duplicate and how she could create her own for-purpose model here in Australia.

One of the things I love about OzHarvest is the clarity Ronni brings to the role it performs and to the growth of the organisation. As she clearly articulates, OzHarvest operates under four pillars:

- Food rescue. Wasted food is collected and distributed to those who most need it.

- Environment. Good food worth between $8 and $10 billion is wasted in Australia every year, millions of tonnes going straight to landfill. Keeping it out of landfill directly benefits the environment.

- Education. OzHarvest teaches vulnerable people how to purchase and prepare good food on a very limited budget, how to eat better and how to maximise the impact of good food on their lives.

- Community engagement. OzHarvest seeks to inspire, connect and create opportunities for those in the community looking to get involved but without the capacity, desire or commitment to start their own organisation. The charity is creating a pipeline for volunteers to connect more deeply with their community and to feed their souls at the same time.

It's the fourth pillar that attracted to me to OzHarvest. Ronni says, ‘Community engagement is so important for the emotional health of our country. Creating an opportunity for people to give back and to do good for others is hugely important. It is about a civil society and I believe it is the way a society is measured’.

Community engagement is a key to OzHarvest's success. The organisation depends on volunteers and provides meaningful opportunities to more than 100 people every month. Part of this is creating gainful engagement that allows the volunteers to see the difference they are making, have that shared experience and feel good about themselves at the same time. The experience starts when the volunteers collect the food and develop an appreciation of the waste that would occur but for their work. Their experience is deepened when they then get to deliver the food and see the change it brings to those receiving it.

Right there is the magic, the reason why I chose to feature OzHarvest. It's not because of the great work it is doing and the number of lives it is changing among those who consume the food, but because of the number of lives it is changing among those who deliver it. An outsider could measure its success based on the number of meals it provides to those who might otherwise go hungry, or in the tonnes of landfill avoided, or in the delivery of the education programs it runs. But that would be to miss a great part of the success of what it does and who it serves.

Ronni describes the meaningful experiences provided for the volunteers as the ‘very core’ of their success. It's why the corporates they engage with stay with them. ‘Our corporate partners support us in a number of ways, one of which is the provision of their staff, who come along and have an amazing experience and they love us. In turn they go back to work and love their employers a little more, who complete the circle by loving us even more.’ It is to the experiences that bring a deeper level of engagement that Ronni attributes much of their success.

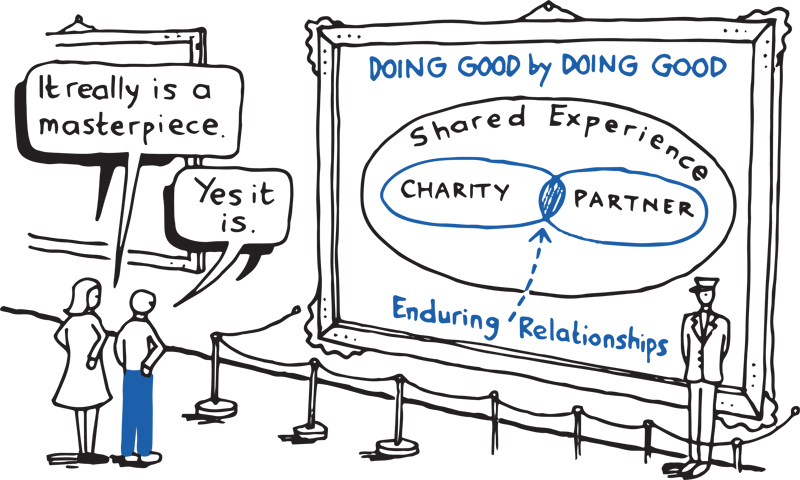

It is a great example of how a corporate and a charity can work together to create shared value for one another. That's the very essence of doing good by doing good.

Humpty Dumpty Foundation

The Humpty Dumpty Foundation is an Australian charity founded by Paul Francis OAM, who remains the executive chairman. The original purpose of Humpty was to support the pediatric ward at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney. Since Paul first set about helping sick kids in 1990, the reach of Humpty Dumpty has grown from one ward in one Sydney-based hospital to more than 214 hospitals across Australia, impacting on tens of thousands of families along the way. It has also recently started supporting a hospital in East Timor.

What it does is life-changing and without a shadow of a doubt life-saving. It stops children from dying. Listening to Paul talk about the origins, the success, and the stories of the kids and how it interacts with its supporters, you begin to understand how this humble, quiet-spoken man has led the organisation over the past twenty-odd years with controlled passion, a vision and deep resolve. Few appreciate the challenges of balancing the competing demands of maintaining a business career and a family while running an active charity; fewer still manage to do all three successfully for over a quarter of a century.

The foundation owes its success to the simplicity of its focus. For Paul and his team it is very clear that it's all about giving their supporters an outcome. It is a classic example of satisfying the ‘but for’ test I have spoken about throughout the book. Paul can walk a team of supporters through a hospital and point to the equipment in the theatre, emergency room or wards that sustains the most vulnerable children. He can point to equipment displaying the ‘Donated by Humpty Dumpty’ stickers and say, ‘Without your donation and commitment, this little fella in the bed here would not be alive today’. I'm not sure there are too many experiences more powerful than that.

And there's no need to break it down and explain how much of the donation will go towards one place or another. They don't talk about improving the survival rate of sick or injured children across the country. They remove the complexity, telling their donors, ‘Here is a list of equipment that is needed in these hospitals across the country. If you would like to purchase a piece of equipment we would love your support. You choose the value of your contribution and you choose the hospital you would like to support’.

Requests for equipment come to the Humpty Dumpty Foundation from the 214 hospitals it supports across the country. Each request is submitted to a task force of appropriately qualified people, who make recommendations on what the foundation should support and what it should not. The task force must be satisfied that the equipment is not going to sit in a corner and never be used and that the equipment is appropriate to the operational level of the hospital. Once the task force submits its recommendations, Paul and his team put each request into language that can be understood by non-medical people: this is why it is needed and this is what it is going to do. The list of equipment needed is then collated and put before the sponsors or donors, who are then invited to purchase a piece of equipment for a hospital of their choice to the value they choose, with a commitment that the hospital will receive it within 12 weeks. The final decision rests with the individual donor. At the end of the night, when they leave the function at which the invitation is presented, they can go home and tell their kids what change will occur because of their support. A powerful position.

Paul admits that when he started with this model of offering to ‘sell’ the equipment at fundraising functions he was not filled with confidence it would be successful; in fact, he feared the strategy would fail miserably. He needn't have worried. At his first attempt he raised $30 000 and all the equipment was purchased within minutes. Today Humpty raises upwards of half a million dollars at its events using the same strategy. With that kind of success why would you change.

Changing a model that works is always risky. Paul's decision to start supporting hospitals more than 30 minutes’ drive from Sydney's North Shore was a leap in the dark. All of his supporters in the early days were located in a small catchment area on the North Shore, and what brought them together was tennis. When requests for support came from the Children's Hospital at Randwick and then Westmead, he was nervous as to how this would be received. The donors were now being asked to consider supporting a hospital that in all likelihood they personally would never visit or need to call upon. Paul could have put forward an argument for why it was necessary or explained how the foundation planned to expand, or even just started distributing the money raised across the hospitals. Instead he simply gave them the option of supporting at the level and location of their choice. His faith in them was confirmed as they eagerly dug deep to support all the hospitals, not just those they might one day need themselves.

The East Timor decision followed the same pattern. The option was put to 200 of its supporters: ‘Should Humpty Dumpty support a hospital in East Timor?’ The result: 199 voted for and just 1 against. Power rested with the donors to choose who they would support.

When I ask Paul and his general manager, Angela Garniss, why they think it is such a success, they respond in unison: ‘It's the experience!’ I can see the pride Paul feels when, leaning forward in his chair, he shares the following story.

‘We had a donor who had spent $21 000 to purchase a laryngoscope for Royal North Shore Hospital. A three-year-old little fella by the name of Lachlan had been taken to the hospital. All of the equipment on hand and the experience of the medical team were put into saving this little boy, but it wasn't working. They couldn't remove the blockage from his throat. They had recently received the laryngoscope from our foundation, but there was a reluctance to use it as it was so new. Confidence wasn't high due to their unfamiliarity with the equipment, but the options for saving Lachlan's life were fast diminishing — other than using the laryngoscope. Such was the uniqueness of the procedure that it was recorded on video for training purposes. It was successful and they did save Lachie's life.

‘What we know very clearly is if they hadn't had the laryngoscope Lachie would not be alive today. We were then able to play the video at our next fundraising event to show the difference it had made. Better than that, we had the medical team who used it to save Lachlan's life and we had Lachlan's parents at the same event to celebrate the success. You can imagine how the donor who had purchased the equipment felt when he got to meet the medical team and Lachie's parents. This is an example of the shared experience that we are able to create.’

When Paul started putting on fundraising dinners, many of his friends said, ‘I'll give you $100 rather than come to your dinner’. Paul had been around the block too many times to let that be the outcome. ‘Get them to the dinner and the $100 they were going to spend quickly turns into $2000.’ In Paul's experience, too many charities think because they are a charity they can get away with serving potential donors a low-quality meal or cheap wine. Paul is clear that if he wants to attract corporates and expects them to bring along their clients, it needs to be a memorable night, an experience that gives them a great night out, and that includes good food and exceptional wine.

What value do his donors and corporate partners take from their relationship with Humpty Dumpty? Paul answers the question by recalling the words of one of his donors: ‘You taught me how good it feels to give.’ The team at Humpty sees the sense of purpose that grows within a company when it gets behind a project and can see for itself the outcomes that are a direct result of the giving. ‘We create the opportunity for people to give and then we see the benefits they get from that giving. Sadly, too many people miss out on the pleasure of giving.’

From the moment I met Paul and Angela it was clear to me that they are doing remarkable work and that many families across Australia today are complete thanks to them. That is obvious very quickly. But what is equally clear is the value they attach to the experience they offer their donors and supporters. Paul speaks about the end result, saving children's lives, by telling stories. The foundation is about connecting their donors to an outcome. From the choice of wines served at their functions to personal tours through hospital wards with their donors, he is convinced that the way to success for Humpty Dumpty is to create shared experiences. Do it effectively and the task of saving lives can be left in the skilled hands of the medical teams across the country.

✽ ✽ ✽

In the previous pages we have discussed the experiences of bike rides in Thailand, of feeding the hungry and of providing medical care for children in our hospitals. These three charities are profiled because they do experiences well. In emphasising the value of shared experiences for the participants and the charities, there is a tendency to focus on the event itself. If we focus solely on the shared experiences that each of the charities offers, however, we risk missing the bigger picture. We need to consider the relationship above and beyond the actual experience.

The relationship is what brings the two together in an enduring way. The memories of shared experiences — the hard days on the bike, the smiling faces of the children and the many hilarious moments on the road — don't end when the riders climb off their bikes for the last time. The memories and experiences live on. But what do we do with those supporters who have committed so much of themselves over a 12-month period or the sponsors who have purchased the life-saving medical equipment? The dance doesn't have to be over when the music stops.

After many years of running a charity, I know there is a tendency to finish one major event, such as the bike rides in January, draw breath and take a couple of weeks off before starting again, moving on to the next event. But could we do something more to extend the experience and keep the relationship alive well after the wheels have stopped turning? My feeling is yes we could, and we absolutely should.

How do you extend the experience you have created to provide added value to your participants, sponsors or donors? Exploring the success of the charities I have featured in this book, what emerges clearly are both the consistencies and the simplicity of the models. That's not to say the operations are simple and without immense challenges. To suggest that would indeed be to deny many of their triumphs. The simplicity is in the translation of what they do and how people can make a difference. The progressive charities and those who do social value well can best articulate it through storytelling.

When it comes to clarity in measuring input and outcomes, TOMS offers one of the simplest and therefore one of the best models. One for one. Three words describe how it converts its charity dollars into doing good. As a supporter you understand what you need to do to produce a given outcome in a developing country.

OzHarvest has a very clear message: ‘For every dollar we receive we can deliver two meals to someone in need.’ That is really powerful stuff and is a compelling argument when you are sitting in front of potential donors, corporate partners or even your most loyal supporters. If you have the clarity, can satisfy the ‘but for’ test and have transparency, then that will massively boost your credibility and trustworthiness.

Humpty Dumpty can't offer quite the same simple formula, but what it can do on a much higher level is connect donors to sick, sometimes terminally ill children through telling powerful stories of how children's lives are saved. There can be few better examples of satisfying the ‘but for’ test than telling a donor, ‘Tonight you have purchased this piece of equipment, without which children have died in the past’. As with TOMS and OzHarvest, the basic model is simple, with a direct correlation between the donation and the difference made. Again, no messy formulas and totally believable — and the advantage of being able to tell corporate partners the story, or better still take them on a tour of the hospital.

When you are making incremental improvements to a community, and projects run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, the challenge of finding the ‘one for one’ increases. At Hands we are able to break down the cost of caring for each of the several hundred children across our multiple homes; we can identify the costs per child for food, education and so on. But what we have found most successful is providing very clear fundraising targets for each of our riders (the main source of our income). If the riders are participating on a corporate ride of five days, they raise $5000; if they join one of our longer rides, they raise $10 000. The figure is not negotiable, it's not a target to get close to. The rider who doesn't reach the $10 000 target doesn't ride.

The Hands model involves a very different level of engagement from buying a pair of shoes as a contribution. Both, however, make it very clear to the potential supporter what they need to do and where their contribution will go. Supporters will always look to engage on different levels. We see that at Hands, where some supporters may choose to visit one of our centres but that is the sum total of their support, while some riders return year after year, raising another $10 000 each time. The charities that continue to grow are those that have found a successful way of engaging with their supporters. The sponsored bike ride model won't be for everyone; buying a pair of TOMS shoes may or may not feed your soul. The key is to find your place in the market and create a unique experience.

When I am working with other charities or talking with corporate teams about building engagement through shared experiences, I list my five experience essentials:

- Start with the question ‘How can I add value?’.

- Be clear why you are doing it.

- Believe in it or don't do it.

- Become known for it.

- Ask, ‘Does it feed my soul?’.

Let me explore these in a bit more detail.

- Start with the question ‘How can I add value?’. At Hands when we are looking to engage with a new partner, or even when we are sending out a monthly newsletter, one question I ensure we ask is ‘How are we adding value in this exchange?’. My view is that if we are talking with sponsors around an exchange of money, and that is the sum total of the conversation, I have not done my job effectively and the connection is likely to be limited. In everything we do we need to start from the place of knowing how we are going to add value to the experience. What will create the best environment for the supporter, donor or visitor to our centre so they will want to return and deepen their level of engagement?

- Be clear why you are doing it. It seems pretty straightforward, but what is the purpose behind the experience you are creating? What is it you want to walk away with, and what is it you want those involved in the experience to walk away with? Once you are really clear on why you are doing it, then you can build a framework to maximise the opportunity. As a charity, do you want high participation rates, heavy exposure, low overheads or major fundraising as your biggest outcome? You can't have them all, so choose your most desired outcome and put your efforts into making that a success.

- Believe in it or don't do it. Creating those experiences that are really meaningful and have the power to change lives, both of the recipients and of the participants, can and often does take massive amounts of time and resources from an organisation to be successful. To continue to invest these resources the team needs to believe in the purpose and the vision. Without belief and authenticity true potential won't be realised.

- Become known for it. An easy measure of success of the experience you are creating is when you become known for this as much as for the core business. Many of our corporate riders sign up for the first-hand experience and engagement. The outcome of bringing change to the lives of the kids in Thailand is almost secondary. For a good number of our supporters both in Australia and internationally, Hands is mainly about the rides. This in no way detracts from what we are doing on the ground; quite the reverse, it enhances what we are able to achieve. Get the experience right and the money will come.

- Ask, ‘Does it feed my soul?’. This is closely connected to point 3, but it takes it to a deeper and more meaningful level. If you can achieve this then everything else becomes so much easier. For me on a personal level, riding 1600 kilometres every January with the people that come and join us is food for my soul. I get to experience the ride with those I love most in my life, and we bring amazing success to the charity. I get to witness the personal journey of the riders, and it is a privilege to be part of something that is so meaningful. The ride changes lives and provides food for the soul for many who otherwise find themselves caught on the hamster wheel of life.