Chapter 1

IS THERE A BETTER WAY?

Do you need to change your current approach to corporate social responsibility (CSR)? Before we can answer the question we need to define CSR and some of the typical approaches to it we see.

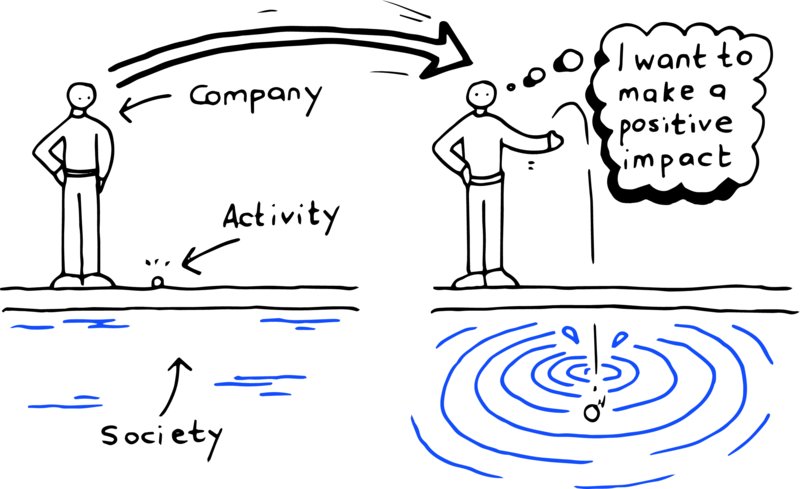

All organisations have their own interpretation of their programs and have the discretion to attach a definition that works best for them. But what is at the core of corporate social responsibility? Well, if you suggested it is about ‘how companies undertake their activities to optimise a positive impact on society’ you would not be too far off the mark.

Or you might choose a rather more robust definition such as the one formulated by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in its publication Making Good Business Sense by Lord Holme and Richard Watts: ‘Corporate Social Responsibility is the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the local community and society at large’.

Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) has adopted the following definition: ‘Operating a business in a manner that meets or exceeds the ethical, legal, commercial and public expectations that society has of business’. Finally, the European Commission prefers: ‘A concept whereby companies decide voluntarily to contribute to a better society and a cleaner environment. A concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis’.

We could fill the chapter with such definitions but that would get tedious very quickly. The common thread is that it is about businesses conducting themselves in ways that benefit the community. It might be as simple as donating a sum of money once a year to a charitable organisation. Or it might be much more complex and include integration throughout the company, including indexing remuneration to sustainability measures, as is the case at Unilever Global. The proposition that CSR can be so much more than corporate philanthropy leads us towards the concepts of shared value and conscious capitalism. Both of these ideas sit outside the common model of CSR and offer a new view on how business can be done.

A paradigm shift

If you ask most employees what their company's CSR strategy is, they would typically answer along the lines of ‘our company supports charity XYZ and they give me one day off a year to volunteer with a charity of my choice’. What many would identify as the sum total of their CSR strategy most likely accounts for less than 50 per cent of the commitment made by businesses towards the community as part of their CSR model. As we will see, in 2014 Optus made a commitment of $9.7 million to its community programs, with $300 000 or just over 3.2 per cent in cash.

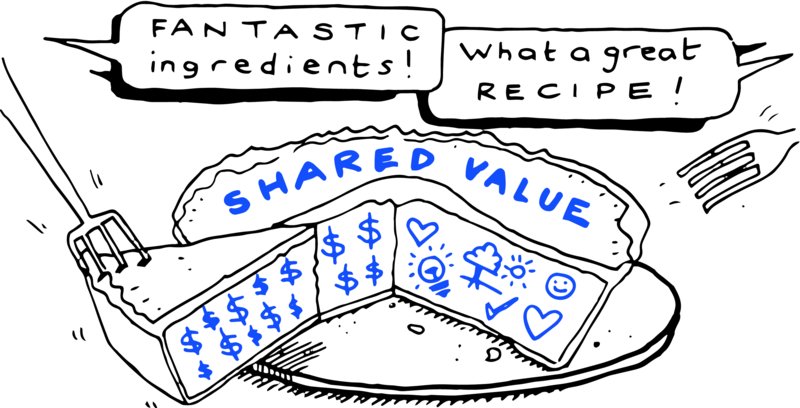

The concept of shared value by its very name points to a value exchange between business and the community. Business creates economic value and at the same time creates social value by addressing the needs and challenges that exist in the community. Shared value is not about cause marketing or programs such as employee giving, employee volunteering or matched giving programs. It looks for opportunities within new markets that address a community need, incorporating the entire value chain into the process and the concept of local cluster development.

Conscious capitalism is another spin on how business can work with the community to create benefits on both sides of the ledger. The term is attributed to Muhammad Yunus, who in 2006 was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his 1983 creation of the microlending institution the Grameen Bank. John Mackey and Raj Sisodia, the authors of the 2013 book Conscious Capitalism, argue that there are four specific tenets at play: higher purpose, integration of stakeholders, conscious leadership, and conscious culture and management.

Mackey and Sisodia's view is that ‘business is inherently good because it creates value, it is ethical because it is based on voluntary exchange, it is noble because it can elevate our existence, and it is heroic because it lifts people out of poverty and creates prosperity’. They argue that companies who embrace conscious capitalism create positive impacts for customers and their employees, and also suppliers, communities and the environment. The authors argue that this results in better experiences for the customer, and lower costs and more growth for companies.

They suggest that CSR is a part of conscious capitalism, which sits above the concept of CSR. It seems fair to conclude, however, that many of the advantages and benefits they see as accruing from the concept of conscious capitalism are embraced by the more mature CSR programs. Conscious capitalism certainly embraces a concept of deeper integration with all stakeholders, which is not necessarily part of your typical CSR program.

Drawing a clear distinction between conscious capitalism and shared value is more difficult and potentially a matter of semantics. Both conscious capitalism and shared value are based on the idea of businesses working more closely with their community partners and improving their profitability by doing so. Advocates of both propositions nominate companies who integrate the fundamentals throughout the company. Shared value looks to create new lines of business through addressing a community need, while conscious capitalism focuses less on new markets than on improving the mode of operation.

In an article for the Ivey Business Journal, ‘A Case for Conscious Capitalism: Conscious Leadership through the Lens of Brain Science’, authors Srinivasan S. Pillay and Rajendra S. Sisodia distinguish conscious capitalism from CSR, shared value and other models as a way of ‘doing business that goes beyond the ideas of philanthropic thinking or virtue in that it is meant to create an entirely new structure for businesses whose financial integrity rests upon the following: the thought processes inherent in purpose-driven leaders; creating multifaceted value for all stakeholders; leading through mentoring, motivating and developing people rather than through diktat or simple reward and punishment incentives; aligning leadership style with organizational purpose, and creating a culture of trust, authenticity, caring, transparency, integrity, learning and empowerment’.

While Pillay and Sisodia may suggest that the match of values, leadership and going beyond philanthropic thinking is what sets it apart, advocates of shared value would suggest these components are of equal importance in their model.

Shared value, conscious capitalism, triple bottom line, blended value — call it what you will — what is clear is there is a different way of doing CSR. An opportunity exists to move on from the thinking that simply giving money to charity will bring meaningful returns. At the core of the various models that seek to operate above traditional CSR is the need for external engagement with their operations and strategies.

The traditional approach

The traditional approach to CSR has focused on corporate philanthropy. It is the simplest form of giving for companies and individuals alike, and the untied funds provided to charity groups can be the most welcome form of donation. If it is the easiest way for corporates and individuals to give — and certainly it's easy for charity to receive funds in this way — does that mean it is necessarily the best model? We know that easy in life doesn't always mean best, and that is certainly true in this case.

The qualifier to this discussion, though, is do the players involved here want more than they currently get from the relationship? Giving money, whether as an individual or as a corporate, can be the least engaging way of interacting with a charity. But who says engagement is the desired outcome? By giving money you can end the conversation and relationship quite quickly, and perhaps that is a desired outcome. By giving you have been seen to have ‘done your bit’, but by choosing just to give money you have limited your engagement and that might suit you.

Structured workplace giving programs are one of the simplest forms of giving. Companies like them because they are easy to implement, usually entailing little or no expense to them; the employees like them because they are pre-tax, set-and-forget donations; and the charities like them because it is often money for jam. But where is the engagement?

If you have no desire to divert resources away from core business and are more than happy to make an annual contribution, then you must accept the returns from that giving strategy will be limited also.

Is the issue, then, a lack of desire to create a more engaging experience or a lack of understanding of the opportunities that exist? I believe it is the latter. Australians constantly rank in the top 10 of donors on a per capita basis across the globe. But are we engaging in the most effective way of giving, and does the current model encourage growth?

The current model of most CSR programs, which is limited to one-off donations, matched grants and/or volunteering days, imposes an invisible ceiling on the sector, limiting potential and growth. Who then misses out? Well, everyone involved. The companies and individual donors don't capitalise on their donation and the charities aren't necessarily turning their donors into advocates and storytellers.

Missed opportunities

So where are the missed opportunities and why has it gone wrong when the intent to help is pure — or is it? In ‘Beyond corporate social responsibility: Integrated external engagement’, an article from McKinsey & Company (John Browne and Robin Nuttall, ‘Beyond corporate social responsibility: Integrated external engagement’ McKinsey & Company, www.mckinsey.com/insights, March 2013), authors John Browne and Robin Nuttall looked at the sector and came up with four serious flaws that are factors in CSR programs not working.

First, head office initiatives rarely gain the full support of the business and tend to break down in discussions over who pays and who gets the credit. The view outside of head office is that it is something they are often not consulted on; they haven't been involved in the selection process so why should they support it?

Second, centralised CSR teams can easily lose touch with reality and tend to take too narrow a view of the relevant external stakeholders. Managers on the ground have a much better understanding of the local context, who really matters and what can be delivered. Without that communication process across all levels of the company the initiative quickly comes to rest with a small head-office team who are often managing this on top of their normal functional responsibilities.

Third, CSR focuses too closely on limiting the downside. Companies often see it only as an exercise in protecting their reputations, allowing them to get away with irresponsible behaviour elsewhere. Effective external engagement is much more than that: it can attract new customers, motivate employees and build a better company.

Finally, CSR programs tend to be short-lived. Because they are separate from the commercial activity of a company, they survive on the whim of senior executives rather than on the value they deliver. These programs are therefore vulnerable when management changes or costs are cut.

The common thread in the four areas identified is the lack of any shared value. The CSR programs have been built for the wrong purpose and are run by the wrong people, and they are certainly not resourced as a normal business unit would be within the company.

In the past decade or so the mining industry has converted workplace safety, which used to be an add-on or even a hindrance, into a normal function that is evident in every part of the business. From senior management and site leaders through to contractors and site visitors, safety is at the forefront of how they operate. Why? Because it is good for business to be safe. The workers need to return home safely to their families after each shift. But the cost of workplace injuries also drove the change. So operating an unsafe workplace was no longer acceptable. When something like safety is driven through every aspect of doing business, it is no longer a negotiable condition or something that's nice to have when business is going well; it is present regardless.

Within the mining industry they have been able to identify the costs of injuries in the course of business. Those costs may be related to loss of productivity, workplace investigations by regulators, fines imposed or union demands. Reducing injuries improves internal relationships between management and union bodies, creates an environment for better morale and increases productivity. No one doubts the commercial benefits — businesses that are safer will be more profitable.

CSR hasn't attracted the same type of leverage that safety has in the mining sector, in large part because of the inability to calculate the cost savings or gains from doing it well. It is often seen as sitting on the periphery of business and therefore it doesn't have the same advocates willing to drive it through the organisation. Unlike safety it is not mandated, regulated or enforced by legislation, and the reporting remains discretionary. For this reason the benefits to business need to be articulated and championed from the highest levels of the organisation.

A way forward

In addition to suggesting what is wrong with the current model, John Browne and Robin Nuttall, in the report ‘Beyond Corporate Social Responsibility: Integrated external engagement’, also propose a way forward. ‘The logic is simple and compelling. The success of a business depends on its relationships with the external world — regulators, potential customers and staff, activists, and legislators. Decisions made at all levels of the business, from the boardroom to the shop floor, affect that relationship. For the business to be successful, decision making in every division and at every level must take account of those effects. External engagement cannot be separated from everyday business; it must be part and parcel of everyday business.’

The authors distinguished four key principles that applied across the various industries and companies with which they worked: define what you contribute; know your stakeholders; apply world-class management; and engage radically.

Defining what you contribute doesn't mean changing your purpose for existence; it means determining clearly what you contribute to society. The greatest contribution is not in the end-of-year donation; it is in the overall benefit that is derived from the entity. ‘It doesn't mean abandoning a focus on shareholder value; it means recognizing that you generate long-term value for shareholders only by delivering value to society as well.’

The second key principle the authors found was in the value of knowing your stakeholders as well as you know your clients or customers. An in-depth knowledge of your partners means you are aware of trends and opportunities that might arise and build meaningful relationships.

In relation to the third and fourth principles, applying world-class management and engaging radically, the authors observe: ‘A lot of companies start engagement too late. The natural temptation for many busy and cost-conscious executives is to delay acting until something hits them. That can be fatal’. Implementing change when it is not required and diverting resources from core business takes courage and tolerance by the board and the senior executive team, and buy-in from stakeholders. As the Chinese proverb goes, ‘The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago; the second best time is now’.

The authors conclude: ‘A good relationship with NGOs, citizens, and governments is not some vague objective that's nice to achieve if possible. It is a key determinant of competitiveness, and companies need to start treating it as one. That does not mean they have to initiate philosophical inquiries into social responsibility and business ethics. But it does require them to recognize that traditional CSR fails the challenge by separating external engagement from everyday business. It also requires them to integrate external engagement deeply into every part of the business by defining what they contribute to society, knowing their stakeholders, engaging radically with them, and applying world-class management. In other words, it requires the same discipline that companies around the world apply to procurement, recruitment, strategy, and every other area of business. Those that have acted already are now reaping the rewards’.

Constraints on the charity sector

So if we accept the proposition that CSR in the form of corporate philanthropy will only ever produce limited returns, and we acknowledge that there are better ways of doing business, does that mean that the change required can or should be led by the corporate sector? What role does the charity, not-for-profit or for-purpose sector have in leading, or at the very least contributing to, the change? And do they have their own backyard in order, so as to make doing business on a more engaging level with corporate appealing?

Perhaps the problem is less to do with the business community not wanting to engage with the NFP sector and more to do with the business community acting with caution or trepidation when it comes to engaging with external partners with less control than they would have if they were part of the supply chain. If the NFP sector acted and performed more like business, would it make doing business with them more compelling?

In 2010 the Australian Productivity Commission released a report into the charity and not-for-profit sector in Australia. The report was the outcome of an extensive review of the entire sector and made recommendations addressing deficiencies and outlining directions for improvement. It posed a number of questions and made many observations that remain as relevant today as when the report was released.

Given how slow the charity and NFP sector is to move, it shouldn't be a surprise that many of the concerns identified in the report remain true today. The commission considered the nature of innovation and what is restraining those leading the organisations from adapting to changes and being progressive in their approach to fundraising and indeed problem solving. Chapter 9 of the commission's report ‘Promoting Productivity and Social Innovation’ made the following observations:

‘Not-for-profit organisations (NFPs) face greater constraints on improving productivity than many for-profit businesses. These include difficulty in accessing funding for making investments in technology and training, lack of support for evaluation and planning, prescriptive service contracting by government, and in some cases resistance to change by volunteers, members and clients.’

Part of the reason for the lack of enthusiasm for embracing change and innovation can be attributed to the very sector itself, the returns to those working within and the expectations on performance. Many internal and external observers have the view that charities are doing a ‘nice job’ that is ‘good’ for the community. There are a couple of views that prevail in society when you talk about the role that charity plays. The progressive view is that the future of charity rests with business, which will fill the gaps and lift up developing countries through social enterprise or shared value. They will be prepared to tackle the problems that exist locally and globally as they find ways in which to benefit commercially from the problems, which when viewed differently become opportunities. The theory Dan Pallotta promotes in his TED talk ‘The way we think about charity is dead’ supports business filling the gaps as those opportunities are realised, but he acknowledges that even then there will be at least 10 per cent for whom business and social enterprise will not provide the answers, and consequently there will always remain a role for charity as we know it.

The second and more mainstream view is to consider the NFPs as plugging the holes between government and corporate. I'm sure many consider the services as non-essential to the advancement of society as we know it. If we assume that attitude does exist, there is little wonder that NFPs don't feel the same pressure to adapt, improve and innovate as a commercial entity does.

If an NFP is supported by a group of volunteers, or a small paid (usually well below market value) workforce, at what point do they cease to be commercially viable? In the commercial marketplace success is measured by the return to investors and clearly their end-of-year success or otherwise is reported in a balance sheet; but what of the NFP? They will provide end-of-year reports showing their income versus expenditure, but if their income drops, or the gap between income and expenditure diminishes, the services they can offer just decrease. Shareholders seldom demand improvements and changes. Many of the ‘shareholders’ of the NFPs are silent recipients whose voice goes unheard by those calling the shots.

Without the commercial pressure to drive change and innovation within the NFP sector, where will it come from? Does the pressure to lead change rest with the leadership team and boards of these organisations? You would expect so, as they are the ones who set the direction and vision, and who drive operations towards achieving the goals set in the strategic plan. But where is their incentive to innovate and take risks? We know that if you want a risk-free organisation, if you want to eliminate mistakes, then perish the thought of innovating. Without risk there is no innovation. Speaking about risk in his book Poke the Box, Seth Godin observes, ‘The cost of being wrong is less than the cost of doing nothing’, but the NFP sector seldom rewards the risk takers.

In this sector it is deemed acceptable to pay less than true market value because ‘we're a charity’ (often said with slowly blinking eyes and a puppy-dog face). It is also considered wrong for the CEO of a large charity to be remunerated anywhere close to what they might be able to attract in the for-profit sector. So if you are not paying them appropriately in the first place you are highly unlikely to pay them bonuses or reward them for driving change or taking an innovative approach to business. What is bred, then, throughout the sector is the ‘steady as she goes’ approach, and when this is adopted those who were relevant run the risk of quickly becoming irrelevant, as social entrepreneurs step into this space and are prepared to lead with risk and innovation.

As the Productivity Commission report summarises the situation, ‘NFPs’ natural inclination to take innovative approaches to social problems is being restricted by the increasingly risk averse attitudes of funders and boards; limited resources; constraints on investments in knowledge; and reluctance to collaborate with other NFPs’.

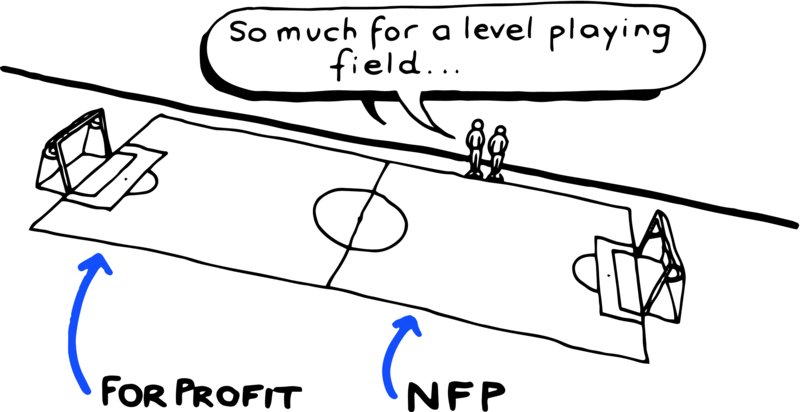

Two different rule books

Dan Pallotta has a view on the charity sector, and a divisive one at that. He challenges the way charities operate, compensate their staff and market the good they do. The interesting thing on the division that he has created through his views is the debate within the charity sector, which can best be summed up as they either love him or hate him.

So what makes these views so divisive and how could they possibly contribute to creating a better relationship between the corporate and NFP sectors?

Firstly, what is he saying that is creating so much angst? If you were to sum it up in one word it would be disparity. He suggests that there are two different rule books; one for the for-profit sector and one for the not-for-profit sector. The disparity that exists presents itself in five main areas.

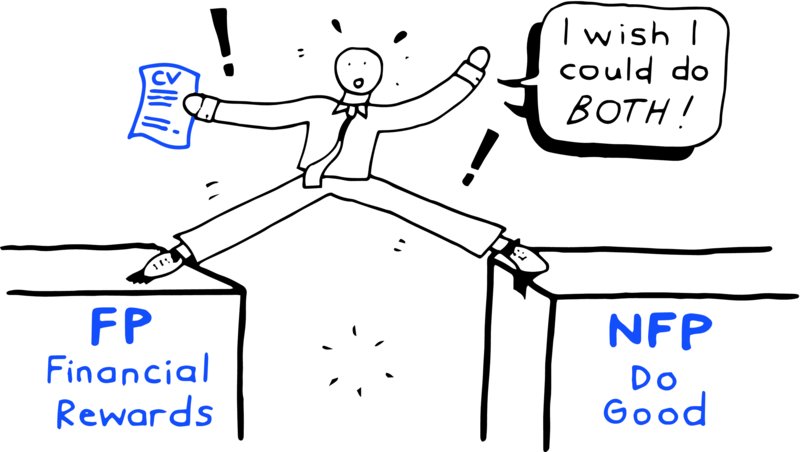

Compensation

Probably the second most contentious issue within the NFP sector, after the total amount that a charity spends on administration, is that of staff remuneration. If a charity CEO was paid an annual salary of $500 000 there would more than likely be an uprising and the CEO would be attacked as a parasite or worse. As Pallotta notes, however, the CEO of a company making violent video games earns $50 million a year and is put on the front cover of magazines as a success. Why, then, do we hold the view that someone who decides to devote their life to ending cancer in children, for example, shouldn't be equally well compensated? ‘The model as it exists right now is you can do well for yourself and your family and be financially rewarded or you can do good for the NFP sector, but you can't do both.’

The best business minds that society produces graduate from university and head straight to the corporate sector to make their wealth. Twenty or thirty years after entering the corporate world they decide to leave and then look for a job that feeds their soul in the NFP sector. But the NFP has been handicapped by the fact that it has had to wait the 20 or 30 years for the smartest to accumulate the wealth to support their lifestyle, knowing it won't be coming in from the NFP sector, no matter what their skill base or the salary they can command in the corporate world.

Advertising and marketing

People don't want their donations spent on advertising or marketing; they want them spent on the needy. As the head of an international charity, I see this time and time again. The more mature donor will acknowledge that in running a multimillion-dollar business, which is what Hands Across the Water is, there will be expenses, and many will agree that to compete you need to spend part of your revenue on the running of the business. But ask them if their preference is for their donation to go into building a new home for at-risk children or to pay the salaries of administration staff working in Australia running the charity, and it is very clear where they want their money to go. The mature investor in charity will acknowledge the need to spend money, but they'd prefer it not be their money.

Dan Pallotta says that people are sick of being asked to donate money, which they see as being the least they can do. He says that people want to be asked to contribute in more meaningful ways to the causes they feel passionately about. Pallotta created long-distance bike rides and walks for charity. In a nine-year period more than 182 000 people participated. They were able to reach these numbers through advertising and marketing, by spending the charity's funds to grow the participation rates. They used the funds to buy full-page ads in The New York Times, The Boston Globe and advertise on primetime TV and radio.

Pallotta points out that giving in the US has remained consistent at 2 per cent over the past 40 years, which indicates that the NFP sector has not been able to wrest any of that spending from the for-profit area. Whether you agree or disagree with his views, he mounts a challenging argument that something needs to be done differently, because we can't continue to do the same thing and hope for a different outcome.

Tolerance of risk

The debate within the NFP sector when it comes to measuring effectiveness is over what constitutes a suitable measure. There is a strong voice that dollars spent on administration shouldn't be used as a measure. A regular (absurd, I would suggest) comment is that those spending low or no amounts on admin are home to scams or are grossly ineffective. These voices, I would suggest, hail from charities that aren't too happy with their level of spend or accountability and therefore want to disregard that measure. They propose that another useful measure might be the effectiveness of the charities. This sounds reasonable, and I have a director on the Hands board who often challenges us by saying, ‘It's great that we don't spend donors’ money on administration, but the equally important question is “are we spending donors’ money in the most effective and efficient ways?”.’

Is there a risk in measuring effectiveness of the charity? Well, it depends whether you measure it over the life of an individual campaign or in relation to the impact that you have on an annual basis. The risk when you start measuring on success or failure is you breed a culture that becomes intolerant of risk, and risk intolerance kills innovation. The NFP sector cannot survive without the opportunity to innovate. It is through innovation that the solution to many of the challenges the NFP exists to address will be found.

Time

In talking about the time afforded to business, Pallotta cites the example of Amazon, which took six years before it turned a profit. Imagine if a charity were to take the first six years of fundraising to build its base before helping any of those in need. Such a position would not be tolerated and indeed would likely be illegal; at the very least it would be difficult to imagine the funding for such a model continuing beyond a year or so. Building Hands Across the Water, the greatest change to the income that flowed into the charity was on the back of the completion of the first home. Credibility runs parallel to success in the charity space. The more you are doing the more you are likely to receive, which allows you to continue to do more.

Currently the NFP sector faces the problem of an inability to attract people into the sector at equal compensation levels. Those working within the sector don't have the freedom to compete for market share by advertising or marketing, and there is a low tolerance for risks or mistakes, which hampers innovation. With anything that is done, results need to be produced pretty quickly as we don't have the time afforded to those in the for-profit space.

Capital

The for-profit sector can raise additional capital by selling shares in the business, which allows the business to grow, acquire or invest in new infrastructure. They have the ability to use their profits in various ways. The only source of capital open to the NFP sector is raising donations.

A need for balance

If we want to change the face of charity and increase the services we are offering, three real options exist:

- We drive overheads down within the NFP sector by reducing the spend on salaries, advertising and administration. We ask the CEOs to take home less, even though we accept they are paid well below what for-profit CEOs can command.

- We spend more in the NFP sector to drive growth. Our ultimate aim is that donors, through successful marketing and advertising campaigns, and even a shift in consciousness, increase their giving, which provides us with more to spend on social services.

- We create opportunities for social entrepreneurs through the concept of doing good by doing good.

The first of the three options is flawed and unsustainable if we want to see any real growth. It flies in the face of most of the informed commentators in this space, from the thoughtful Dan Pallotta through to the authors of the Productivity Commission report and those in between. Innovation, leadership and growth within the NFP space requires investment, which will allow competition and ‘air time’ with the for-profit space.

Increasing the level of giving will generate a larger pie and greater access, but giving alone is not the answer either. The creation of shared experiences will enable people to be involved, to feed that part of their soul that currently goes hungry.

The third option, of creating more shared value between business and charity, goes to the heart of allowing people to satisfy their need to do well and build a good life for themselves while also allowing for the community around them to prosper. This model does not rely only on the generosity of the giver. Power does not sit with one side alone; it is shared. This creation of mutual dependence ensures that each side has an interest in the continuing growth of the other.

The question that then emerges is how do you create enough value for people to cross the road to do business with you as opposed to one of the hundreds of others like you?

You don't have to agree that Dan Pallotta's way forward is the right one. He has had successes and failures but there is merit in a number of his propositions. Perhaps his strategies are really best suited to very large charities. But it is hard to argue with the facts around the limitations that exist within the NFP sector when competing with the for-profit sector.

So when we suggest business should consider changing the way they engage with the NFP sector or work towards a model that more closely represents shared value or conscious capitalism, perhaps we should also be suggesting the charity sector make some fundamental changes if we want a different type of relationship.

As a footnote to this discussion on the charity sector, as chairman of Hands Across the Water I have a self-interest. In this chapter I have advocated appropriate remuneration of NFP staff, and I support the freedom of charities to commit appropriate resources to marketing, advertising and, importantly, to the development of its staff. I firmly believe that there is a need for balance to create a more level playing field between the FP and NFP sectors. But these views are not in support of my personal position. As the founder and chairman of Hands Across the Water, I receive no payment for the time I allocate to the charity. I cover all my own personal expenses and the charity operates from a position that 100 per cent of all donations go to the children and projects we run in Thailand. Not one cent of donors’ money is spent on administration or fundraising. The model on which Hands was created makes it possible to operate under these principles.