3. Six Sigma Launch Philosophy

With Ian Wedgwood

This chapter covers some general philosophical principles that have driven successful Six Sigma deployments in the past. Six Sigma is more than focusing on the money, finding the money, and delivering the money, as mentioned in the previous chapter. Six Sigma deployments, if done well, actually end up changing the culture of the organization. This was clear in the Motorola experience.

In just a couple of years, everyone in the company knew how to calculate a Sigma and was driven by the metric, defects per unit (dpu). Companies that have been successful with Six Sigma find that they operate much differently than before Six Sigma. For example, companies hear, “Where’s the data to support that idea?” more often. The demand, “We’ve got to put some Black Belts and Green Belts on that issue,” is heard frequently. Project identification and prioritization become more systematic and timely. Reward and recognition programs are ubiquitous, mainly because there is always some amazing result to be proud of. The nature of Six Sigma means you have to get better at a lot of things before Six Sigma is successful.

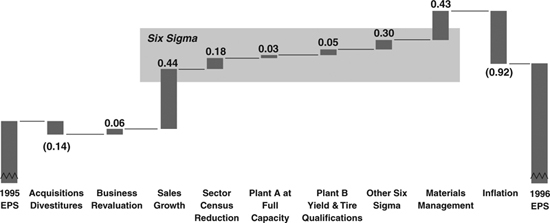

Six Sigma represents the methodology for pursuing breakthrough improvement in business performance. Figure 3.1 shows some actual data from a Six Sigma company (AlliedSignal). The graph depicts the company’s 1995 earnings per share of publicly traded stock, and then compares 1995 results to its 1996 earning per share. This image, the financial bridge, shows the real difference from 1995 performance to 1996 performance directly from Six Sigma activities. AlliedSignal started an extensive Six Sigma initiative in 1994. This figure shows that AlliedSignal achieved about a 14 percent growth in earnings per share because of the Six Sigma activities during 1996 alone.

Figure 3.1 The Six Sigma financial bridge tracking the financial impact of Six Sigma on earnings per share from 1995 to 1996.

Six Sigma accounted for approximately $1.43 per share. Notice that the activities marked “Plant A at Full Capacity” accounted for $.03 per share. Not bad for a 23-year-old chemical engineer from Louisiana State University and her plant team. Her team optimized a new chemical plant in Baton Rouge after over a year of the “experts” trying to figure things out. These results were directly transferred to their sister plant in France, adding another $.05 cents per share.

The Nature of a Six Sigma Deployment

Now that we’ve seen that Six Sigma is correlated to business and financial breakthroughs, there are many components that make up a Six Sigma deployment. The first step of the deployment philosophy is to establish the business. Just as any new business needs a business plan, so does deploying Six Sigma. Six Sigma—especially when including Lean Enterprise—includes many different business applications.

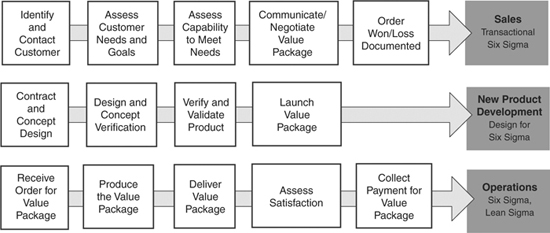

While Six Sigma addresses the accuracy of systems and Lean Enterprise addresses the speed of systems, the two methods integrated provide a powerful combination. At least three applications of Six Sigma combined with Lean Enterprise include (1) manufacturing operations, (2) business process support, and (3) new product development. Other specific applications include marketing, sales, supply chain management, safety, and enterprise systems. So, deciding the scope of the Six Sigma deployment and where to focus is critical at the onset of the deployment. Therefore, different processes use different forms of Six Sigma and their outcomes, as follows:

• Transactional Six Sigma for business processes: Optimizing process flow or designing new processes.

• Operational Six Sigma: Optimizing product and process flow.

• Lean Sigma: Products and special tools for process flow, speed, and accuracy.

• DFSS (Design for Six Sigma): Products, operations, and market windows.

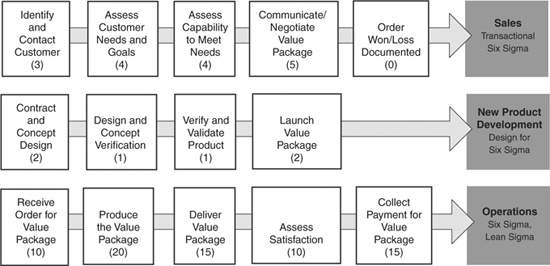

In Figure 3.2, three typical core business processes (sales, new product development, and operations) are shown, along with the appropriate Six Sigma application. Here we see just a small fraction of the core business processes in a typical company—sales, product development, and operations. You notice the option to track your Six Sigma projects by determining to which process box the project applies. Figure 3.3 shows for each box in each process in Figure 3.2 a number in the lower box that indicates the number of Six Sigma projects identified for that particular process step. The figure shows this company is covering operations very well, but may change the focus to development and sales. If you have empty boxes, your Six Sigma program is not serving that part of the company.

Figure 3.2 Matching Six Sigma form to the business core process.

Figure 3.3 Matching Six Sigma to the business core process. The numbers in the lower center of each box indicates the number of Six Sigma projects that are underway.

So, now, when you line up your important core processes, you can easily see how you might overwhelm your Six Sigma program from the start. The secret is, based on the external realities, prioritizing the core processes and starting with a relatively few important core processes at the beginning allows you to evolve your Six Sigma program over a few years.

For example, AlliedSignal was directed to focus the first year of Six Sigma (1994) on manufacturing operations. In 1995, Six Sigma was moved into R&D and product development. In 1996, transactional Six Sigma was initiated. AlliedSignal knew that if it tried to do too much too soon, it would not be successful.

Six Sigma Deployment Timing

Just to start an effective Six Sigma deployment, the company has to consider, at minimum, these activities:

• Selling the concept to the organization: Internal marketing plan.

• Systematically attain quick results (6–12 months) early in the deployment:

• Lean and Kaizen activity.

• Well-defined strategic projects.

• Create a structured project identification methodology:

• Prioritized list of projects.

• Define a “project hopper” for future projects.

• Strategic mapping and assessment activities to focus the projects in the right areas.

• Launch a supporting infrastructure:

• HR, finance, project tracking and reporting, Six Sigma steering teams, and Champions.

Of course, there are many additional milestones, but the preceding gives you an idea of the magnitude and the complexity of launching a successful Six Sigma deployment. The purpose of this book is to give you definitive guidelines with which to launch Six Sigma within 90 days. Now it’s time to look at the philosophical architecture.

Kotter’s Philosophical Deployment Architecture

I have drawn the Six Sigma deployment architecture from the fine work of Harvard Professor John P. Kotter and his book, titled Leading Change, published in 1996. The book is excellent and, because driving change is the most difficult task in a company, the book took the corporate world by storm. Kotter keeps things clear and reasonable. He was, in fact, invited to address the senior leadership of Larry Bossidy’s AlliedSignal soon after Six Sigma was deployed. It is clear to me that Larry had used Kotter’s ideas and produced terrific results.

John Kotter focused on the idea of transforming the organization. As a Harvard professor, in his studies, he’d seen common ways that organizations fail in their attempts to execute a transformation. He also defined eight stages that, if followed, will almost guarantee your transformation (i.e., Six Sigma deployment) will be successful. The following are Kotter’s eight stages:

1. Establishing a Sense of Urgency.

2. Creating a Guiding Coalition.

3. Creating a Vision and Strategy.

4. Communicating the Change Vision.

5. Empowering Broad-Based Change.

6. Generating Short-Term Wins.

7. Consolidating Gains and Producing More Change.

8. Anchoring New Approaches in the Culture.

I will now address each of the preceding stages to launching a Six Sigma deployment.

Kotter Stage 1: Establishing a Sense of Urgency

Establishing a sense of urgency is the toughest part of deploying Six Sigma. As Jim Collins says in his book, Good to Great, “Good is the enemy of great.” Kotter says in a complacency-filled organization, change initiatives are dead on arrival. We’ll take a quick look at the ever-present gremlin, complacency. Looking at complacency, several sources appear:

• Absence of a major critical crisis.

• Metrics that focus employees on narrow functional goals.

• Low overall performance standards.

• Internal measurement systems that focus on the wrong performance standards.

• Human nature, with its capacity for denial, especially if people are already busy or stressed.

To create a sense of urgency, some of these sources must be attacked directly. But, let’s go back to the three-component business model, which links (1) external realities, (2) financial targets, and (3) internal activities.

Now there are at least two ways to create a strong sense of urgency. The first way is to identify a crisis. This crisis will be identified by clearly understanding the concept of external realities. Identifying a crisis creates emotional linkage to the change initiative. A crisis may be derived from at least two different sources:

1. The current organization is under siege now or will be soon.

2. The organization will not exist in the long run if things don’t change.

Identifying potential opportunities for success provides the second way to create a strong sense of urgency. Convincing people that the change initiative, Six Sigma, will move the company to greatness is a realistic approach without having to dwell on or create a crisis. The final success of the launch is tied to significant financial targets of the program. That alone will generally provide the sense of urgency that is needed to launch a change initiative.

During AlliedSignal’s 1994 launch of Six Sigma, there were significant financial goals established in productivity and growth. Fred Poses, then the president of the engineered materials sector of AlliedSignal (currently, Fred is the CEO of American Standard), used an optimum combination of opportunity and tough financial targets.

The opportunity, he declared, was based on some calculations literally handwritten on the back of an envelope while eating dinner in a restaurant. From his analysis, he estimated that the combination of lowering the sector’s cost of poor quality and improving manufacturing capacity and yield would lead to at least a $1 billion savings over three years.

I know from my experience leading the Six Sigma effort for Fred that I had a specific goal of $150 million of pretax income by the end of the year. To reinforce that goal, I always heard the same question from Bossidy at the end of our one-on-one training sessions: “Steve, when will all this activity hit the bottom line?” I left the meeting with a real sense of urgency.

Creating a sense of urgency is important, but leading the Six Sigma deployment with courage is the real success factor. Both Larry Bossidy and Fred Poses went through a lot of training and knew the guts of Six Sigma, and more importantly believed in what Six Sigma could do for the company. They both invested a huge amount of time communicating the initiative. I personally watched Fred listen to each of his 30+ general managers explain to him in excruciating detail who their Black Belts were, what the projects were, and how much the projects would yield financially.

Larry held extensive quarterly Six Sigma reviews across AlliedSignal without fail. Larry spent at least 30 minutes with each class of Black Belts that I was training. Most importantly, both Larry and Fred picked the right people to drive the program. The Six Sigma Champions with whom I worked were all accomplished, respected, and passionate about Six Sigma. But it all worked because of a clear sense of urgency right at the beginning. Results backed up Larry and Fred’s efforts. AlliedSignal achieved a two-year financial impact of Six Sigma amounting to about $880 million. Stock values rose accordingly. Six Sigma helped AlliedSignal become a premiere company.

Another example of creating a sense of urgency is 3M. Jim McNerney, a former GE senior executive, was named the new CEO. Within a couple of weeks of taking office, Jim had discovered 3M had been spending a lot of time and resources investigating Six Sigma. Jim made it easy for this group—he dictated that they would launch a three-day Six Sigma training session for the top 100 senior leaders of the company within about two weeks. Because Jim knew the guts of Six Sigma from deploying it into two divisions of GE, when I talked to Jim about my consulting company doing the leadership training, he said,” Yeah, I broke some glass around here.” Jim had helped his staff—which had worked on trying to decide whether or not to do Six Sigma for over a year—to decide to do Six Sigma in only a few days.

He also explained to me that he wanted the fastest Six Sigma deployment in history. And he did it! Within three weeks of the leadership session, which got a standing ovation, hundreds of projects and Black Belts were launched. Now, 3M literally has thousands of projects going simultaneously, and 3M’s performance in the stock market matches the effort. Jim was able to be so courageous because he knew in his heart that Six Sigma was the right thing for 3M.

Jim set tough financial expectations for the Six Sigma deployment: (1) getting products to market faster; (2) improving cash flow; and (3) improving productivity. He grew Six Sigma into an additional initiative—3M Acceleration—by meshing Design for Six Sigma into 3M New Product Introduction (NPI) process. This was a great move since this initiative built on 3M’s tradition of product innovation.

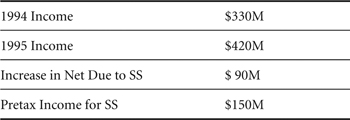

One other way to establish a sense of urgency is to be clear about the cost of procrastinating in Six Sigma. In an early presentation to the leadership of AlliedSignal’s engineered materials sector, Fred Poses (President) and Donnee Ramelli (VP of Quality) presented the financial target, which was pretax income of $150 million additional dollars. The table looked like this:

Our Goal in 1995

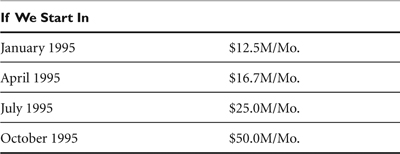

The preceding chart said that, through effective Six Sigma deployment, the financial target was $150 million of pretax income—not a small number for a $4 billion sector. But then the urgency was actuated. Fred and Donnee presented a table that expressed the average monthly benefit that Six Sigma would have to deliver, depending on when each organization started. This was presented at a meeting held in late 1994 to drive for results in 1995.

1995 Monthly Improvement Required

The point was clearly made. If you sprint right at the beginning of training Black Belts, you had to average about $12.5 million a month to meet the $150 million goal. But if you waited until July to start, you’d have to average about $25.0 million per month, almost twice as much as the January implementers. This was very effective in getting the organization fired up to get started. In fact, even when we started two classes (or waves) of Black Belts in January 1995, I received several complaints from leaders who were asked to wait until the second class started to send their Black Belt candidates. They claimed the extra two weeks of waiting was going to kill them.

The sense of urgency is primarily the product of great leadership. One CEO claimed that when launching an initiative, “You have to change the people or change the people.” For an initiative to be truly internalized, you must have all your senior leaders on board and at least the vast majority of everyone else. The CEO had replaced a number of his senior leaders at AlliedSignal to communicate the sense of urgency. Fred Poses replaced one plant manager very quickly because that manager didn’t take Six Sigma seriously. Believe me, all the other plant managers became extremely interested in the initiative. The following chapters address in detail establishing a sense of urgency:

• Chapter 5, “Strategy: The Alignment of External Realities, Setting Measurable Goals, and Internal Actions”

• Chapter 6, “Defining the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

Kotter Stage 2: Creating a Guiding Coalition

Creating a guiding coalition leads to establishing a group of the right people who have enough power and leadership ability to lead the Six Sigma deployment. There is also the challenge of creating a team of people who have the capability of working as a team. Companies successful in deploying Six Sigma have a clear commonality. They are smart enough to put a strong and credible leader at the helm of the deployment.

In AlliedSignal, Larry placed a newly acquired Vice President of Manufacturing, Richard Schroeder, in charge of the deployment. Rich was very experienced in Six Sigma from his history with Motorola, and he also drove Six Sigma into ABB as well. Rich had a double reporting structure: (1) CEO and (2) VP of Quality—Jim Sierk. So the combination of starting with someone who knew the guts of the program and giving him a clearly high reporting line set the stage for success.

The next step was to create several “boards of directors” or steering teams in each of the three AlliedSignal sectors: (1) aerospace; (2) automotive; and (3) engineered materials. The president of each sector was requested to identify Six Sigma Champions. This group of about 60 people attended a one-week training session very early in the deployment. Because the original focus of Six Sigma in AlliedSignal was on manufacturing operations, these Champions were the cream of the manufacturing crop. They were all leaders with credibility and respect in their sectors.

Some other examples of starting off Six Sigma with a guiding coalition would include Cummins, 3M, and Celanese. Each of these companies carefully selected the Six Sigma leader. The Cummins (a manufacturer of diesel engines) CEO, Tim Solso, selected Frank McDonald to lead the program. Frank was probably Tim’s best operations expert, so Tim knew Frank would make it happen. Frank, of course, was a little confused at first, being moved from the operations role he loved, to being the corporate quality guru. He initially thought he was being punished, but as he learned the guts of the program, he soon realized he could change Cummins into a different company, which he did.

At 3M, Jim McNerney selected Brad Sauer, a highly respected up-and-coming business leader. Brad was a strong leader and the perfect person to lead the program. Brad, after leading the first two years of Six Sigma, was given a business to lead. At Celanese, a large chemical manufacturing company, the President, David Weidman, was a former AlliedSignal business leader working for Fred Poses.

Dave knew operations, the guts of Six Sigma, and knew in his heart that Six Sigma was the right thing to do strategically for Celanese. He put his best operations person, Jim Alder, at the helm of Six Sigma. Once again, Jim, being an ops guy at heart, thought he was being punished with his new role. It was not long before Jim figured out that, by driving Six Sigma, he could make Celanese a better company, which he did.

Carefully selecting the leader of the initiative cannot be underestimated. The selection of the Initiative Champion is the first shot across the bow in a Six Sigma deployment. The person selected will tell the entire organization how important the initiative is. Larry Bossidy, in his recent book, Confronting Reality, says that picking the right people to implement the initiative is extremely important. Look to his book to get his insights on this matter.

In the three companies discussed, the CEOs selected the right leader carefully, and then the new leaders surrounded themselves with an effective deployment team—usually referred to as Deployment Champions. In all cases, the deployment team received at least a week of Six Sigma training and participated in the deployment planning—generally with the help of an outside consulting group. These CEOs also changed the reward structure, usually putting a hefty percentage of their bonuses on results from deploying Six Sigma.

There is also the steering team side of deployments. While at AlliedSignal, I created several steering teams that were accountable for some aspect of Six Sigma. These steering teams literally served as my boards of directors for their part of the program. I found that if I created the steering teams correctly, I could effectively transfer accountability for results to the team. Some examples of steering teams were the following:

• Manufacturing Council

• Equipment Reliability Council

• Chemical Laboratory Council

• Financial Council

• Human Support Steering Team

These teams help define the appropriate Six Sigma roadmaps, devise the deployment plan for their Six Sigma program, determine the strategic direction of their program, and report results on financial targets.

The following chapters cover aspects of creating a guiding coalition in great detail:

• Chapter 8, “Defining the Six Sigma Infrastructure”

• Chapter 10, “Creating Six Sigma Executive and Leadership Workshops”

• Chapter 11, “Selecting and Training the Right People”

• Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment”

So, it’s on to Kotter’s third stage of creating major change.

Kotter Stage 3: Creating a Vision and Strategy

When you hear the word “vision,” you probably immediately remember very long vision development meetings and, like most people, you hated it. I won’t talk about how to create a vision, even though I have had good luck with vision meetings that lasted about 1.5 hours and produced a vision everyone in the room liked. But, when launching a major initiative like Six Sigma, the organizational leadership must have a clear and simple vision about what Six Sigma will do for the company.

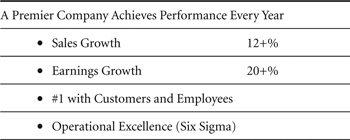

I call these “elevator speeches.” You meet someone on the elevator in corporate headquarters and they ask, “What’s all this about Six Sigma?” If you can’t answer that question before you hit the exit point, you don’t have a clear idea of what Six Sigma is all about for your company. This is the vision presented by Fred Poses to his leadership for the engineered materials sector, which was based on AlliedSignal’s corporate vision:

This vision was simple, clear, and effective. A leader could easily explain it on the elevator. For Paul Norris, then CEO of WR Grace, the vision was easy. He put an overhead slide on the projector at the leadership training session, and it had one number on it—$100 million—and that’s what he said he expected from the program. Because Paul was an alumnus from the AlliedSignal Six Sigma experience, everyone in the room knew he was serious and knew what he was talking about.

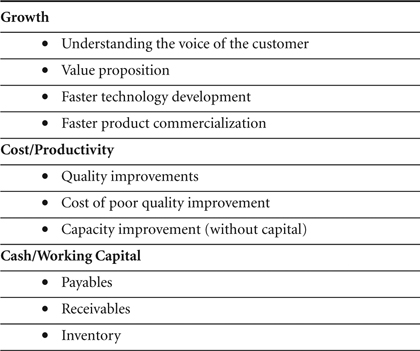

The strategy part of launching Six Sigma is an output of linking the three business model components: (1) external realities; (2) financial targets; and (3) internal activities. The strategy is made up of the initial Six Sigma deployment plan, the long-term strategic development of Six Sigma, and developing the roadmap for leading Six Sigma over the long term. The following chapters address creating a vision and strategy:

• Chapter 4, “Getting Early Support: Selecting a Six Sigma Provider”

• Chapter 5, “Strategy: The Alignment of External Realities, Setting Measurable Goals, and Internal Actions”

• Chapter 6, “Defining the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 7, “Defining the Six Sigma Project Scope”

• Chapter 8, “Defining the Six Sigma Infrastructure”

• Chapter 9, “Committing to Project Selection, Prioritization, and Chartering”

• Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment”

• Chapter 15, “Leading Six Sigma for the Long Term”

Kotter Stage 4: Communicating the Change Vision

Communicating the upcoming change widely and clearly is absolutely necessary for change to occur. Communication plans are complex because they have to use a wide variety of communication forums. But there are some guidelines on effective communication of the Six Sigma initiative.

The first guideline is simplicity. Making the change clear and exciting is best with simple communications. Repetition of the simple message is crucial. Larry Bossidy and Fred Poses were the best I’ve seen. In every meeting and every event they attended, they had a short, dynamic message. They both relied on multiple forums and media. Fred was very consistent about calling and leading leadership conferences addressing Six Sigma.

Both Larry and Fred attended multiple Black Belt and Green Belt sessions to deliver their message. Larry once said you have to communicate an initiative so often that you finally want to throw up every time you say it. Well, I assume he exaggerated, because I never saw him throw up. The point was understandable—you might be willing to commit to the change if you’re always talking about it in a repeating message.

And, finally, there must be many give-and-take opportunities for all members of the guiding coalition. And, Kotter recommends the creation of a verbal picture to use often. You will see the following chapters address communicating the vision:

• Chapter 10, “Creating Six Sigma Executive and Leadership Workshops”

• Chapter 12, “Communicating the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment”

• Chapter 14, “Defining the Software Infrastructure: Tracking the Program and Projects”

The following is an example of a vision for Six Sigma actually developed at the onset of the Six Sigma deployment:

Our Six Sigma Commitment to Drive

Kotter Stage 5: Empowering Broad-Based Change

You’re in luck here, for Six Sigma capitalizes on empowering employees to support the company’s goals. That’s the only way your Six Sigma program is going to work. Let’s go back to the three-component business model, which links (1) external realities; (2) financial targets; and (3) internal activities. Simply, by understanding your external realities and creating a strategy to address those realities and setting your financial targets to reflect your external realities, you must align your internal activities to get the results you need.

After your strategy is defined to address the challenges of your external reality, your guiding coalition will work on identifying and prioritizing projects that directly support the strategy. Of course, the guiding coalition will need a large amount of training to make this happen.

After these projects are identified, each organization must select and train the right people to apply Six Sigma to complete those projects. The major focus is naming and training Black, Green, and Yellow Belts. Great projects drive the training success, which consists of defining great projects and resources for the project teams before the student attends his or her first training session.

When the Belts attend training with projects that are obviously tied to business and strategic success, the training becomes a way to accomplish those goals. The challenge of the first 90 days is planning for the Black, Green, and Yellow Belts in Operations, R&D, and Transactional areas.

Now, when you consider that AlliedSignal trained over 450 Black Belts during the first full year of Six Sigma, that means there were at least 450 resourced projects with an average of 10 members on each project team. Thus, at least 4,500 people were empowered for broad-based action. That didn’t include Green Belts because not many were trained the first year. Every member of every team understood where the project fit in helping to make AlliedSignal a premier company.

So, after you understand what your company’s performance gaps are based on the external realities, you define a strategy to close those gaps, select projects identified in fixing the gaps, and train Belts and apply resources to their teams; you automatically empower employees for broad-based action. That’s when Six Sigma gets very exciting. The chapters addressing employee empowerment are as follows:

• Chapter 5, “Strategy: The Alignment of External Realities, Setting Measurable Goals, and Internal Actions”

• Chapter 6, “Defining the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 7, “Defining the Six Sigma Project Scope”

• Chapter 8, “Defining the Six Sigma Infrastructure”

• Chapter 9, “Committing to Project Selection, Prioritization, and Chartering”

• Chapter 11, “Selecting and Training the Right People”

• Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment”

• Chapter 15, “Leading Six Sigma for the Long Term”

• Chapter 16, “Reinvigorating Your Six Sigma Program”

Kotter Stage 6: Generating Short-Term Wins

This phase consists of planning for, creating, and rewarding those early wins. In reality, early results are the best way to drive change. However, the results must be clear and convincingly substantial. For example, within the engineered materials sector of AlliedSignal, the six-month yield of Six Sigma projects was about $50 million. Six Sigma definitely had the sector’s attention. Every plant manager was almost evangelistic about the program.

There is clearly an opportunity to launch your first wave of Six Sigma training within 90 days of your first deployment milestone and start posting financial results within another 3–6 months. The deployment strategies documented in this book has short-term wins as its focus. The chapters that apply to generating short-term gains are as follows:

• Chapter 4, “Getting Early Support: Selecting a Six Sigma Provider”

• Chapter 6, “Defining the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 9, “Committing to Project Selection, Prioritization, and Chartering”

• Chapter 11, “Selecting and Training the Right People”

• Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment”

• Chapter 14, “Defining the Software Infrastructure: Tracking the Program and Projects”

Kotter Stage 7: Consolidating Gains and Producing More Change

Pending a successful Stage 6 that produces dramatic early results, the next step is to grow the Six Sigma initiative with other focused projects. For example, AlliedSignal focused on manufacturing operations during the first year, and then added emphasis to growth by launching Design for Six Sigma (DFSS), and later started Transactional Six Sigma. Each new project has the same accountability to the financial targets as the first project.

This stage migrates Six Sigma to include all parts of the company. Usually, the first migration for U.S.-based companies is to launch Six Sigma in Europe and Asia. As Kotter quotes, “Culture changes only after you have successfully altered people’s actions, after the new behavior produces some group benefit for a period of time, and after people see the connection between the new actions and the performance improvement.”

People will see over and over again Black Belts dropping $250,000 to $1,000,000 to the bottom line—project after project. They will either want to be on a project team or be trained as a Black Belt. Simply, however, as stock prices continue to go up, change becomes easier. The chapters addressing consolidating gains and producing more change are as follows:

• Chapter 5, “Strategy: The Alignment of External Realities, Setting Measurable Goals, and Internal Actions”

• Chapter 7, “Defining the Six Sigma Project Scope”

• Chapter 8, “Defining the Six Sigma Infrastructure”

• Chapter 12, “Communicating the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 14, “Defining the Software Infrastructure: Tracking the Program and Projects”

• Chapter 15, “Leading Six Sigma for the Long Term”

• Chapter 16, “Reinvigorating Your Six Sigma Program”

Kotter Stage 8: Anchoring New Approaches in the Culture

After the Six Sigma deployment is successful, you have to start thinking about what you need to do to make sure the company is doing Six Sigma 10 years from now. Even the Six Sigma pioneer, Motorola, which had launched Six Sigma in 1978, found Six Sigma lacking in the late 90s. This phase leads to the understanding that the change initiative—in this case, Six Sigma—has to be reviewed at least every three years with respect to reinvigorating the initiative.

Anchoring an initiative is directly related to the infrastructure and systems developed to support the initiative. Fortunately, the very nature of Six Sigma addresses developing streamlined processes and systems. So the systems developed to support Six Sigma should be user friendly and effective.

By consistently pointing out the relationship between Six Sigma activities and organizational performance, a connection is made between the new actions equating to closing competitive gaps. A key to anchoring Six Sigma into your culture will be to develop future leaders who have a realistic view of the value of Six Sigma. It turns out that Six Sigma is a great leadership development program. Jack Welch, while CEO of GE, expected that every high-potential leader would be certified in Six Sigma. Most of GE’s future leaders know firsthand the value of the program and will not let it die.

Six Sigma must have something going for it, judging by the number of CEOs who left Six Sigma companies for a non-Six Sigma company in order to introduce Six Sigma. This list is long, which indicates that Six Sigma should not be difficult to anchor in the culture, but you’d better pay attention to doing that. Chapters addressing anchoring new approaches in the culture are as follows:

• Chapter 5, “Strategy: The Alignment of External Realities, Setting Measurable Goals, and Internal Actions”

• Chapter 6, “Defining the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 8, “Defining the Six Sigma Infrastructure”

• Chapter 12, “Communicating the Six Sigma Program Expectations and Metrics”

• Chapter 13, “Creating the Human Resources Alignment”

• Chapter 14, “Defining the Software Infrastructure: Tracking the Program and Projects”

• Chapter 15, “Leading Six Sigma for the Long Term”

• Chapter 16, “Reinvigorating Your Six Sigma Program”

Summary

We’ve covered Kotter’s model for leading change. The model clearly works for not only Six Sigma, but any initiative. You should always review Kotter’s eight stages and do them sequentially. After you succeed at deploying Six Sigma, you will then have a whole organization that is equipped to launch major change initiatives into the company. You will not only have a viable Six Sigma program upon which you are getting a huge return on investment, but you will have created a core competency to effectively launch change initiatives.