Chapter 2

The Attributes of a Good Coach

Clarke Stallworth glowered at the room full of skeptical editors.

“I used to be really tough.” Then the former managing editor of the Birmingham (Alabama) News grinned.

“When a reporter handed me a story,” he said, beginning to pace, “I knew what was wrong with it and I fixed it! I tore it to shreds!” Stallworth picked up a copy of the local newspaper and ripped it into long, ragged strips.

“And they hated me for it!” he thundered, wadding the torn shreds of paper into a ball.

He kept grinning as he described his conversion from hard-bitten editor who “fixed” copy to hard-driving coach who helped reporters improve their own copy and, in the process, become better writers. He continued working the wad of newsprint as he talked.

“The copy isn’t what it’s all about,” he said, his eyes moving from face to face in the audience. “The reporter’s what it’s all about.”

His eyes settled on an especially skeptical editor, who had been leaning back in his chair, arms folded, head tilted.

“How long do your reporters stay with you?” Stallworth asked.

Uncomfortable at being singled out, the man shifted in his chair. “Eighteen months, maybe,” he answered. Around the room, heads nodded.

“You just get ’em broke in good,” Stallworth said, “and you gotta start all over with a new one, right?”

“Well, yeah,” the editor agreed.

“You know why your reporters leave you?”

The editor shrugged. “The pay stinks,” he said, provoking laughter and more nodding around the room.

“The pay stinks everywhere,” Stallworth said. “Reporters leave you because they aren’t learning anything from you. They aren’t getting any better. Keep teaching them and they’ll stay longer.”

Still gently kneading the wad of newsprint, Stallworth explained the difference between an editor and a coach.

“The editor takes the copy from the reporter and fixes it. The story then belongs to the editor, not the reporter. The editor stays mad at the ‘stupid’ reporter, and the reporter stays mad at the ‘pigheaded’ editor.

“The coach sits down with the reporter and asks two questions: ‘What’s good about this story?’ and ‘How could it be better?’ By the time the reporter answers those questions, she’s ready to fix the story herself. She’s learned how to write better, and the story is still hers. She’s proud of it.

“Instead of being ripped up, the story comes out whole,” Stallworth concluded. Then he carefully opened up the ball of newspaper he’d been holding. It had been restored to a full page.

“There’s nothing magic about it,” he concluded, the grin splitting his face. “It’s just plain common sense.”

Coaching: Definitions and Distinctions

Coaching is a relatively new profession and skill set, and as such, there’s sometimes confusion about what it is and isn’t. According to the International Coach Federation (ICF), coaching is “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential.” Coaching is about creating a positive path forward: it focuses on the future (not the past, unless to learn from it). Coaching focuses on what the client wants, not what he or she doesn’t want (the key of the Law of Attraction).

Solution-focused coaching is about creating the optimal outcome to an issue or moving forward to craft a new opportunity. Coaching isn’t necessarily about “fixing” a problem—it can be brought into play when a person has a lofty goal or pet project that hasn’t been implemented yet, or wants to grow and explore more of his or her potential.

Obviously, as a manager or business leader, you aren’t expected to be a “pure” coach. “Coach” is probably just one of many hats you wear. We know you probably aren’t a professional coach and only a coach. As you read through this chapter, keep your personal role in mind. You’ll be able to tell when the information presented is truly relevant and where it should be adjusted to fit your situation.

Good coaching makes a few key assumptions about clients. Coaches should respect the client’s worldview, treat them as whole and absolutely all right as they are, perceive them as resourceful, and challenge them in playing a “bigger game” and taking a big-picture view. Coaches help clients find the answers and resources within themselves, essentially unlocking their internal genius. Clients who specifically seek coaching will get the most out of it if they are ready to work for a change (chronic complainers generally don’t want to work for a change, they just want to vent or get validation). They look for coaching because they want to move forward and grow beyond what they currently are without being told they are “broken” or “need fixing.”

Distinctions

Coaching is not the same as therapy, mental health services, counseling, guidance, mentoring, teaching, training, or advising. It may overlap some of these areas and can certainly be used in conjunction with them, but it’s not a replacement for these helping techniques. Coaching is not appropriate for every situation and person (some just won’t respond). Luckily, as a manager, you have a lot of other resources for supporting your employees that can be used in conjunction with coaching.

Coaching differs from therapy and counseling in that it tends to focus on the present (to get a snapshot) and the future (to create new possibilities). Coaching is less worried about the past (except to learn from it) and the why of something, and focuses more on the how to move forward. Coaching treats clients as whole and resourceful, exactly as they are. Counseling and therapy are important ways to help people resolve issues that may have roots in the past, where the “why” of it needs to be explored, where it may result in crisis mode, and where the person is not well. Coaching won’t help a person in mental or emotional crisis and should not be used in this case.

Coaching may seem similar to mentorship and giving advice, but there are some subtle differences. A professional coach does not only offer advice or tell a person to follow a certain path. A coach might offer options, which the client can then choose whether or not to take up and commit to. A coach treats the client as an expert in his or her life, and thus fully capable of creating a path and following it. A coach elicits responses from the person, rather than providing “easy answers.” Mentorship can be very valuable in the workplace because mentors may also be experts in the same field as the mentoree, or can offer personal insights and advice a coach wouldn’t have. Giving advice can be appropriate in the workplace, but it’s not the same thing as coaching.

Characteristics of a Good Coach

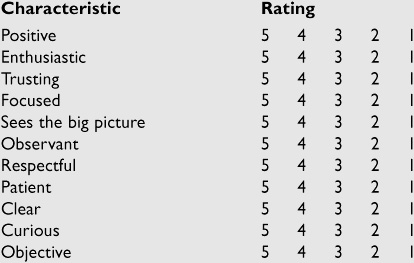

A good coach is positive, enthusiastic, trusting, focused, sees the big picture, and is observant, respectful, patient, clear, curious, and objective. Let’s look at how these characteristics come into play in the workplace.

A good coach is positive. Your job when coaching is not correcting mistakes, finding fault, and assessing blame. Instead, your function is achieving goals by coaching your staff to peak performance. Focusing on the positive means that you start with what’s good and what works, and spend your attention and energy there. When you encourage the positive, you put more attention on it, and your staff will respond in kind.

Mark knows he is supposed to complete his monthly service reports by the fifth. Even though the process is done by online form and seems quick, he is the only IT tech to be consistently late—he usually submits his reports around the 10th. Although he’s been encouraged and then warned about getting them in on time, he still seems to lag behind.

Instead of reprimanding him, try a positive approach. It’s the difference between saying, “Get those reports in by the fifth or else” and asking, “What do you need to do differently to get the reports in on time?”

The first statement reaps resentment and excuses, but no improvement in performance. You continue thinking of Mark as a problem; he goes on thinking of you as a jerk.

The second approach can get you what you want—the reports turned in on time. And you’ve got a shot at winning a bonus—a worker with a more cooperative attitude and improved task management skills to work with.

A good coach is enthusiastic. As a coach/leader, you set the tone. Your attitude is catching. Project gloom and doom, and you’ll get gloom and doom back from your staff. If you concoct reasons why things won’t work out, your staff will never disappoint you—things won’t work out.

Bring positive energy to every encounter. Don’t play it cool. Your staff will respond in kind, with some practice.

A good coach is trusting. Do you expect workers to be infallible, performing their jobs on time, every time, with no errors?

Of course you don’t. Everybody makes mistakes sometimes. Employees have personal crises that interfere with their work. They have good days and not-so-good days, times of peak efficiency and times when they slide into a stupor. Your staff members are human, a characteristic you share with them.

Do you trust employees to be conscientious, tell the truth, and give a reasonable day’s work for a day’s pay? You had better. You shouldn’t hire someone unless you’re willing to extend that kind of trust. Most people are conscientious and honest, with an inherent desire to do their jobs well. When they see you applying high standards to your own conduct, they’ll be even more likely to do the same. Tell them what to do, and then let them do it. Don’t let them catch you looking over their shoulders.

A good coach is focused. The temptation can be overwhelming. While you’ve got the employee in your office discussing current performance, why not discuss the other problems you’ve been meaning to tackle for weeks?

Don’t do it. Don’t take that poor worker on a guided tour of your personal Hall of Horrors.

Effective coaching is specific and focused. Deal in particulars. Keep the task manageable. Keep the conversation focused on the issue at hand, and don’t let it devolve into a gripefest or a venting session. You’re far more likely to get action if that employee leaves your office focused on resolving the issue at hand.

A good coach sees the big picture. “Why does she want me to do that?” If you leave workers pondering that question after you’ve explained an assignment, you’ve only done half the job. You’ve given them the “what” but not the “why.”

Base your assignments on clear, definable goals. Tie specific tasks to those goals. Communicate those goals to the people who actually have to do the work. Help your employees see how their work contributes to the goal, the team, the department, the company, the bottom line, and the overall mission.

Many of us can get blinded by what is happening right in front of us and forget to take a larger view. A good coach can help a person do this. A great analogy for this is that of a football game. If you’re low in the stands, you can only view what is happening right in front of you. From there, it’s harder to see what’s going on in the end zone or the whole field. A coach can encourage a person to “rise up,” maybe all the way to the skybox, to take in a larger view of the game and all its components.

A good coach is observant. A few years back, Tom Peters made “management by walking around” a corporate litany. It’s not good enough, he noted, to sit in your office, even if your door is “always open.” You need to get out and mingle with the troops.

Fair enough. But wherever you are, you need to pay attention.

Being observant means more than just keeping your eyes and ears open. You need to be aware of what isn’t said as well as what is, picking up on body language and tone of voice. Listen to your intuition as well—your gut might alert you when something needs attention.

If you’re paying attention, you won’t have to wait for somebody to tell you about a problem. You’ll see it coming—and may be able to head it off.

A good coach is respectful. Respect everybody around you. Respect their rights as employees and as human beings. This can be as simple as avoiding assumptions or cutting someone a little slack, perhaps overlooking a snappish retort from a worker who’s tired and stressed from a deadline. It can be as complex as learning that a gesture you make frequently to indicate approval comes across as demeaning to someone from another culture.

A good manager tries to learn everything that might matter to the business and then applies that knowledge. Well, your employees certainly matter, so you should learn who they are and treat them all as individuals, with respect. A good coach also respects the client’s worldview. After all, the employee is the expert in his or her own life. When you respect that point of view and make it obvious, the worker will feel empowered, validated, and more engaged.

Along with respect can follow empathy. Being empathetic with your employees lets them know that you see them as human. It helps them feel not so alone. However, be sure you don’t cross the line into sympathy or pity. Feeling sorry for someone else doesn’t do much to help them, and it leaves you with an emotional burden.

A good coach is patient. “How can they be so stupid?!” you wail. “I’ve told them and told them!”

Patience, friend. It isn’t just a virtue—it’s a survival skill in the workplace. Your workers aren’t stupid, and they aren’t trying to drive you crazy. They’re busy, and they’re preoccupied, just as you are. It could also be that they’re ignorant, which is quite different from being stupid. Ignorance is curable, and you’ve got the medicine they need—information and a bigger perspective.

Tell them again, but find other words to do so. Using a new approach, ask them to explain the issue to you, as if you were a new worker (a role reversal that will help them think and see differently). That will show that they understand your directions, and it will help them internalize those directions. Remember the old saying, “To teach is to learn twice.”

You can’t change people, they have to change themselves. Their timeline for change and growth is probably quite different from your own. Don’t expect them to change overnight. Don’t measure everyone by the same yardstick.

A good coach is clear. If they didn’t hear you right, maybe it’s because you didn’t say it right. Maybe you just thought you did.

Everybody has seen it happen. The characters and the setting may vary widely, but the scenario is basically the same: I explain something to you, but you don’t understand, so I repeat it, using essentially the same words, only louder or more s-l-o-w-l-y. The scenario continues, with everyone getting frustrated, angry, and further apart.

Whose fault is it? Yours for not understanding? Or mine for failing to find a more effective way to communicate? It doesn’t matter whose “fault” it is. You and I are not connecting.

Here’s the bottom line: If you’re trying to communicate and the other person doesn’t understand, take responsibility for making the connection. Above all, don’t make matters worse by repeating the same words louder or more slowly.

A good coach will reiterate what the client says, word for word, and even ask “Have I got that right?” to be sure both are on the same page. If the worker seems unclear on what is going to happen next, a good coach will ask her to state it back as she understands it.

A good coach is curious. When you coach someone, a genuine curiosity serves you well. It will make the questions you ask more authentic (instead of “leading” the person to a particular, expected answer). When you are curious, you open the doors to more possibilities, which can elicit more from the employee. If you say, “I’m just curious, what might happen if … ” you offer a way for the employee to dream a bit without the fear of having a “right” or “wrong” answer. The person’s natural resourcefulness starts to come forth. Not every idea will be actionable or implementable, of course, but it broadens the pool of possibilities. Being curious keeps your own mind open to possibilities you might not have thought of.

A good coach is objective. When coaching, especially in the workplace, stay objective as much as possible. Professional coaches don’t express judgment (disapproval or approval) or opinions—a manager is expected to do so when appropriate, however. If you stay objective when coaching, the employee will be encouraged to do so as well.

You can still be positive and enthusiastic while being objective; it just takes practice. Be positive and enthusiastic about the person or the business. A good coaching session focuses on the client’s (or employee’s) agenda, not your own, although as a manager you may set the topic to talk about (behavior, performance).

Being a good coach doesn’t mean you’re passing on your managerial responsibility to make decisions. It means you’re making sure that you understand what’s involved in any decision, that you can communicate your decisions effectively, and that your employees are willing and able to act appropriately. That’s how you get things done.

How did you do? Obviously, 4s and 5s speak well for you as an effective coach. But too many 5s might indicate that you’re dreaming. (Use this reality check: If you asked your employees to rate you anonymously, would your scores be as high?) If you gave yourself some 2s and 1s, you’ve identified areas for personal growth.

But how can you work on being more positive or observant, for example? These are characteristics, after all. You’ve either got them or you don’t, right?

Wrong. That’s a little like saying either you’re born knowing how to do long division or you aren’t. Some people take to long division more readily than others, just as some have an easier time mastering a language or making a balky computer behave. You’ve already learned how to do hundreds of difficult things. You can learn how to develop your coaching attributes, too.

Translating Attitudes into Actions

In the movie As Good as It Gets, at a crucial point in his on-screen relationship with Helen Hunt, the waitress he is ineptly trying to woo, the obsessive-compulsive romance novelist played by Jack Nicholson comes up with what he hopes will be a good enough compliment to prevent her from walking out on him: “You make me want to be a better man.”

It is, she admits, the best compliment she’s ever received. She knows she’s important to him because she inspires him to improve.

In real life, can you learn to be more patient, supportive, clear, and assertive? Sure. You can choose your attitude—if being a better manager matters enough to you. As with most other tasks, you learn by doing—one trait at a time, using positive visualization and at least a three-week trial period.

Interested? Here’s how to do it.

Pick an attribute from the list for which you gave yourself a score of 3 or lower. For this example, we’ll assume you picked “patient.” Develop a clear mental picture of what you look like and how you act when you’re being patient. Visualize it as if you’re looking into the mirror and seeing the patient you. You don’t want an idealized picture of how the Perfect Boss acts. See yourself in the role.

Mentally imagine your most aggressive employee in a highly combative situation. See yourself handling the situation effectively and, above all, patiently.

If you’re doing a good job of visualizing the scenarios, you may feel yourself getting angry. That’s normal. Take several deep, cleansing breaths, and continue working through the scenario, maintaining your focus on patience. What are you doing differently to be more patient? What are the results?

Replay the scene while you brush your teeth, drive to work, or wait for somebody’s voice mail system to kick in. When you feel confident that you’ve grown in the art of being patient, put your visualization into action. The next time you find yourself in a confrontation, bring out your best, most patient self.

This doesn’t mean that you’re repressing your true feelings. You’re in touch with exactly how angry and exasperated you are. You just aren’t acting on or engaging with those feelings. Instead, you’re acting with patience.

To see how much you’ve grown in patience, on the next page, rank yourself again on that 1–5 scale and see how you’ve changed from before you started.

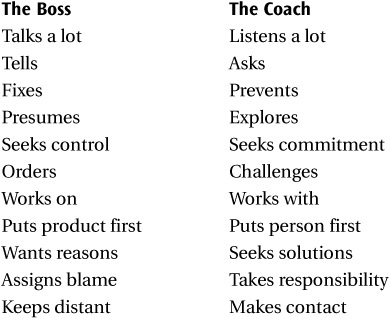

The Boss and the Coach: A Comparison

Here’s how the traits of a boss compare with those of a coach.

In a sentence, the coach lets the players play the game.

Seeing Yourself as Others See You

This suggestion is for the brave: Ask someone to hold a mirror up so you can see yourself in action.

The person who serves as your reflector must be observant, articulate, and secure enough to tell you the truth. And you have to be ready to hear that truth—and act on it.

Explain to this person that you want her to pay attention to your interactions for the next three weeks. Describe the specific behavior you’re trying to change and what you hope to accomplish. Then ask for frequent feedback.

Bringing a reflector into the process can provide two important benefits: (1) you get useful information, in the form of a description of your behavior from an outside perspective, and (2) you’ve increased your investment by adding accountability. You’re a lot more likely to work on your behavior after you’ve told somebody what you’re doing.

The Coach’s Checklist for Chapter 2

![]() Review the definition of coaching and how it differs from other roles in the workplace, like mentoring, counseling, therapy, teaching, training, and advising.

Review the definition of coaching and how it differs from other roles in the workplace, like mentoring, counseling, therapy, teaching, training, and advising.

![]() Evaluate the attributes of good coaches: A coach is positive, enthusiastic, trusting, focused, sees the big picture, and is observant, respectful, patient, clear, curious, and objective.

Evaluate the attributes of good coaches: A coach is positive, enthusiastic, trusting, focused, sees the big picture, and is observant, respectful, patient, clear, curious, and objective.

![]() Follow these steps to develop the traits of a good coach: (1) tackle one trait at a time and learn how to translate it into action, (2) give yourself a chance to make mistakes and learn from your experience, and (3) give yourself enough time to gain competence.

Follow these steps to develop the traits of a good coach: (1) tackle one trait at a time and learn how to translate it into action, (2) give yourself a chance to make mistakes and learn from your experience, and (3) give yourself enough time to gain competence.

![]() Choose someone to be a reflector, someone who can help you see yourself as others see you. Then learn from what this person tells you to improve your coaching skills.

Choose someone to be a reflector, someone who can help you see yourself as others see you. Then learn from what this person tells you to improve your coaching skills.