3

The Design-Minded Enterprise

In order to address complex relationship challenges in the enterprise and come up with an approach, executives in charge of a strategy for the enterprise need an instrument suited to this kind of problem. Beyond the management paradigms of analyzing the past and optimizing the now, determining a meaningful, viable, and feasible future direction requires facilitating a design process—developing insight, synthesizing an approach, generating a vision, and turning this intent into an actionable plan.

The area of design has gained significant traction in business circles, recognizing that it can drive transformation processes and add significant value. In many organizations however, design is still reduced to a very limited role, also due to the self-perception of many designers as stylists without major influence on the conceptual decisions behind a design. Such a design is seen as being merely an ornamentally addition to things that others have invented, or the arrangement of elements others have conceived. It prefers questions where the answer could be anything, like choices of color or visual patterns. It abdicates the responsibility for real decisions to other disciplines. Typically, it is used only at the lowest level, given the least thought and analysis, and obviously falling short of producing any result that matters on a strategic level.

Fortunately, as the discipline grows and matures, more and more professionals realize that any enterprise that benefits from design at a strategic level has developed an understanding that goes beyond this limited view of a superficial afterthought. This Chapter is about using design competency to link viewpoints and tackle strategic issues.

About Strategic Design

Design can be used by hybrid thinkers in connector roles as a strategic tool, to envision a future for the enterprise, regardless of the particular function or level of the organization. Its unique characteristics and capabilities to deal with ambiguous, complex challenges become apparent even in the more traditional industrial or communication design that focuses on tangible and visible outcomes.

Confronted with strategic issues in today’s enterprise context, business leaders essentially face wicked problems when trying to come up with an approach to tackle key relationship challenges. According to research from Gartner, a prerequisite to successfully approaching such a challenge is to be aware that it defies conventional methods of problem solving. There are always parts of a problem setting that are determined by constraints, requirements, and other hard facts, but what makes a pure analytic or inductive approach ill suited is the larger part that is underdetermined or even completely undetermined. The space between problem and solution cannot be bridged by analysis alone.

A design-led approach can be employed to tackle any kind of strategic challenge, by generating a vision of what might be and lead the innovation efforts. However, using such an approach to strategic problems does not exclude other ways of thinking from being successfully applied, such as Process Reengineering or Balanced Scorecards. Those methods to improve quality and efficiency based on measurement and analysis, well suited to optimize the process used to put a vision in place.

In this context, it is critical to identify hybrid thinkers in the enterprise, and to work with them when applying design to a strategic challenge. They provide the basis to steer the conversation, bridge different viewpoints, make sense of the mess, and bring together different approaches.

Example

Imagine you ask a communication designer to come up with a logo for a new company. The result will probably contain the company name, or a graphic to appear next to it, to convey that name as a message. Asked for his or her choices of what is depicted, what color, shapes and fonts are used, the designer might still be able to state concrete reasons - but this already gets quite difficult, because those decisions involve highly intuitive judgment, driven by talent and experience.

The performance of that logo for that company depends on how well it supports the business in establishing, retaining, and renewing relationships to people—the effects of design decisions are almost impossible to predict. That’s why design professionals today consider a logo to be merely a key part of a wider system of visual brand identity, embedded in an individual context of use, perception, and purpose. This enables them to contemplate its function in a system alongside any constraints that apply, and opportunities to stand out. They think about that system being applied in different contexts, instead of just creating an individual artwork in isolation.

![]()

In this example, the problem to be solved is largely undetermined. The number of possible solutions to the given problem—visually representing and differentiating a newly created business—seems to be almost infinite. A large number of decisions made by the designer are impossible to derive from the client brief, because large parts of the problem are unknown or ill defined. The outcome will be part of a larger system of communication, and requires making some completely unconstrained choices (some would call this space the artistic part of design). The proposed solutions can of course be measured against the known requirements, for example, technical feasibility in different media, but this validation is incomplete since the actual success factors of the underlying relationship challenge are unknown.

Instead of thinking something through completely before acting, it requires a blend of analytic, intuitive, and systemic thinking, where the emergent result is just one of many possible outcomes—the essence of a design approach. Solving every detail of a problem is impossible due to the fundamental trade-offs between the decisions, so that a good design aims to achieve a significant improvement instead of a comprehensive solution.

In our experience, most professional designers therefore refer to the quality of design work simply as being good or bad design. Though often impossible to state why, they form an opinion whether a result works (solves the most important issues) and fits (integrates well into context and environment). Key to achieving such a design is the constant endeavor to create something new and fantastic.

From artifacts to strategy

As described earlier, the role of design in most organizations is still far away from realizing its potential as an instrument to make sense of and connect different ideas. This is due to a limited perception of its role, characteristics, and capabilities. Overcoming this state requires involving professional designers who can work beyond the visible, on a conceptual and strategic level.

Most organizations are using design practice to shape signs and objects, as part of brand identity and Marketing, or for Product Design—but they understand its role as one of producing visible outcomes, without any major influence on strategic choices. More conceptually focused design disciplines are rapidly growing both in terms of practitioners and organizations using their approaches. Areas of practice such as User Experience or Service Design redefine behaviors involving interactive systems and services. Only a few organizations seem to successfully employ design practice applied to all sorts of systems, on a level where it informs business strategy formulation in the light of complex challenges.

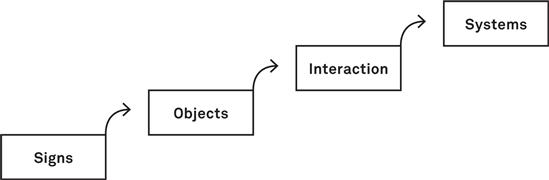

Richard Buchanan developed a framework at Oarnegie Mellon university, differentiating Four Orders of Design with varying levels of influence and types of results. There are different variants of the framework cited in design literature, but we found the following definitions useful to describe different aspects of design:

The Design Of Signs

or first order design, is about designing the symbols used in communication processes, such as in Graphic and Information Design. It is about conveying messages and persuasive arguments, syntax, and semantics, to enable understanding and facilitate information exchange.

The Design Of Objects

or second order design, is about designing physical objects being used by people for some purpose, such as in Industrial Design and Architecture. It is about selecting and using materials, designing tools, and embodying technology, to support usage and integration in a physical context.

The Design Of Interaction

or third order design, is about designing the behavior of systems and considering the actions of people, such as in Interaction and Service Design. It is about designing processes, transitions and activities over time, defining the different states and options to choose from.

The Design Of Systems

or the emerging fourth order design, is about designing dynamic systems and environments, such as in Organizational Design or Design Thinking. It is about designing the transformation of a system’s structures, functions, and flows, taking a hybrid look at the system and its dimensions and constraints.

The four orders can be used to describe four different contexts where design applies, four levels of maturity in thinking about design, or simply four different approaches to address a design problem.

Richard Buchanan’s Four Orders of Design

While the four orders in Richard Buchanan’s framework loosely map to the various fields and subdisciplines in design, it is important to note that any design challenge includes aspects of all four orders, even if hidden from the designer and other parties involved. They are best seen as intertwined layers of design, to be explored in different depths depending on the individual context, as places to generate ideas and foster innovation.

To be employed at a strategic level in the enterprise, design approaches must be inclusive of all four orders, and consciously address the outcomes from a design initiative, from the most abstract to the most tangible. To make that happen, design needs to be embraced and understood in the organization, both to apply design methods to strategic problems and to understand and align the contributions of design professionals.

The Design Competency

In daily life as well as in business, everyone makes design decisions. A design process happens every time separate things get combined, arranged, and aligned to fit a specific purpose, regardless whether those things are kitchen items, project plans, or people in an organizational chart. Design as an approach can be applied by anyone in the enterprise, and certainly anyone can participate in that process and contribute to it. Business professionals unknowingly practice design every day by reinventing parts of the business to address a change, chase an opportunity, or fix a problem. Applying design in a professional manner involves a core set of activities and approaches, and also offers a large variety of methods and tools. This section is an overview of the design approach and profession, and provides a basis for applying the framework and methodology outlined in the following parts to enterprise design challenges.

Example

A building used as corporate headquarters is a good example of Second Order design according to Richard Buchanan’s framework, because of its physical manifestation and the dominant role of the architect. Depending on the individual project, however, it might also be seen as a symbol as in First Order design, playing a role in the organizational communication or brand identity. Its interiors are used by staff or other people to work, collaborate, or meet with clients, all activities that can be explored using a Third Order design approach. Finally, it can also be seen as part of the enterprise as a socio-technical system, a physical context and infrastructure for its work culture, service provisioning, and operational functions, and therefore an example where Fourth Order design can be applied.

Headquarters of China Central Television, Beijing

Understanding people

Most design philosophies are based on a fundamental understanding of the people you are designing for. Traditional market research as used in Marketing practice or requirements elicitation has a place to inform design, but merely with the goal to develop a thorough understanding of the context, not to derive any direct conclusion or design decision from them. Going beyond quantitative research and collecting stakeholder opinions as requirements, design research seeks to generate deep insight into human reality, including environment, daily routines, concerns, and aspirations.

Using ethnographic methods and modeling techniques, this research strives for immersion into the lives of those being addressed by a design. By undertaking field studies, observation and inquiry in context, and qualitative methods, it dives into the very details of the design problem. Any such research benefits largely from involving professionals with a background in a people-centric discipline and who are familiar with empirical methods and social research. However, a significant goal is to expose any team member involved in design decisions to real people, to view the things from their point of view in the actual context, and to develop both knowledge and empathy.

In the enterprise context, design research expands further to include all stakeholders impacted by or involved in a transformation. Understanding their motivations, goals, and context via immersion and empathetic thinking enables us to address stakeholder concerns on an entirely different level, and to understand the technology and business side of the problem represented by those stakeholders. Besides conducting research work directly with people, designers gain knowledge secondary desk research, drawing insight from structures, culture, environment and physical artifacts, domain knowledge, or other sources to further expand their view of the design space.

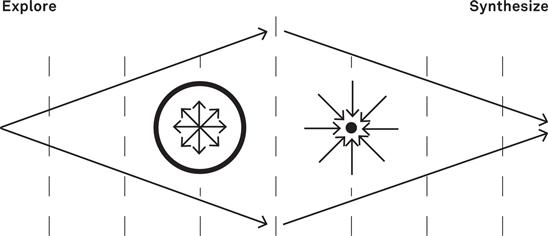

Exploration and synthesis

Based on the research results, the generative activity of design commences with an open exploration phase, by making sense out of a large set of information about the problem space. A thorough design research usually results in a vast amount of seemingly disparate findings and data. This includes transcripts and observations from people research, any quantitative data and analysis available, as well as findings from other methods of research.

It also includes generating ideas and options independent of constraints and limitations, shifting the problem definition to discover hidden spots for improvement and innovation, and challenging known assumptions and beliefs. During the process, the weight of each design decision increases, while new ideas get harder to fit into the design. Simply solving the problem gets more difficult the deeper the exploration dives into the problem space. What seems to be a space of infinite choice at the beginning turns out later to be a wicked mess of related elements and influencing factors to account for, each design decision further constraining the way forward.

The process of exploration and synthesis

In his book Exposing the Magic of Design, Jon Kolko describes the transition from research-based exploration to generating design options as a sensemaking activity, the task of quickly generating meaning out of a lot of data. More than analyzing that data and drawing conclusions, design synthesis introduces new elements into the thinking process by relying on the designer’s experience and inspiration, discussion with peers and experts, and thoughts about feasibility and viability.

The synthesis activity is where the abductive thinking happens, which in the end enables the design process to produce unexpected and innovative results. Findings from the research are connected, ordered, sorted, and related , in order to create multiple models of the design space. This is often done visually, as affinity, flow, or other conceptual diagrams, sometimes using large walls of sticky notes and drawings. It involves reframing the problem to look at it from various stakeholder perspectives, shifting between different aspects, and mapping mental models onto conceptual models. The goal is to define a mental map of the problem, and generate new knowledge by introducing elements from outside.

This is the basis for what Jon Kolko calls experience scaffolding, by providing a framework of elements that characterize the outcome of the design process, and exploring their role in people’s experience. This activity involves exploration of possible paths via sketches, developing narratives to place the design in a context of a person’s life, and expanding the design space to cover the context where it is applied. In design synthesis, the ability to empathize with those people affected by a design guides the decisions, and helps to ground all activities in a real-life context. This placement of potential results in their context of use is the basis for prototyping and validation.

Designing and validating results

The conceptual models, insights, and approaches derived from design synthesis are used to envision prototypes, resulting in interactive models of the outcome of a design process. Rather than just proving the feasibility of a concept to prepare for implementation, prototyping is used in design as a tool for creative exploration, as a thinking aid to try out different directions and further ideation prior to choosing a definite path. It serves as a communication tool for aligning a design with stakeholders and target groups, as a source for further questions and possible directions, and can be used to involve people from outside the core design team into the activities of exploration and synthesis. Instead of discussion, opinions, and compromise, the interactivity of prototypes helps to embed the development and evaluation of designs in a realistic setting.

Prototypes mean different things to different people, but share the common goal to put a design to the test and validate it against the problem space. They are usually different from sketches and conceptual models in the sense that they attempt to capture a certain part or aspect of a design holistically and comprehensively, enabling detailed exploration, testing, and iterative redesign. The nature and effort of a prototype therefore vary widely, depending on what exactly is to be validated and the stage in the design process. Design professionals combine multiple very different prototypes to represent the different aspects of their design using a reasonable effort.

Prototyping is a powerful tool to turn the results from framing and sensemaking into visions of a possible future. The visible, tangible, and interactive part can be used to explore different domains of design work, including simulations of flows in the background such as business processes or financial streams. As the indispensable result of all design work, prototypes indicate the direction of the transition, and help to define and refine a solution leading to its implementation, based on the constant and relentless inquiry for the best possible outcome.

The design profession as a strategic resource

Just as in other professions such as engineering or management, there is a difference between applying a design approach and working as a design professional. In Sketching the User Experience, Bill Buxton asserts that he thinks about design as a profession that is as rich as mathemetics or medicine. It holds room for different philosophies and subdisciplines, a large variety of methods and tools, a lifelong learning and refining of professional skills, and a large and diverse body of knowledge. There are specialist designers working on particular media, subjects, or industries, such as web or interior designers, or even specialists in particular tools.

But design, like other disciplines, is impacted by the convergence of media and technology, causing separate subdisciplines to overlap. Products show some of the qualities of media and behavioral systems, communication media are used as tools, environments are becoming media, and all of them acting as the stage to connect organizations and individuals. A new breed of generalist designers moves towards the third and fourth order design disciplines, and brings together many different design domains to create a coherent response to a problem.

We found that designers working on strategic challenges in the enterprise are not just very experienced, but also tend to have just such a generalist background. They are applying design methods and skills in ambiguous, unfamiliar, and complex environments, to generate visions that are stunning, unexpected, and elegant.

Besides possessing hybrid thinking skills and mixed professional backgrounds allowing them to bring people, domains, and thoughts together into a systemic concept, they possess an eye for outstanding aesthetics, without necessarily doing the visible design part themselves. They find pleasure in elegance both in a mathematical and a visual sense and strive for simplification in terms of structures. They have a preference for clearly arranged systems and unity, but allow for necessary diversity. These values are balanced against a pragmatic idea of the end result.

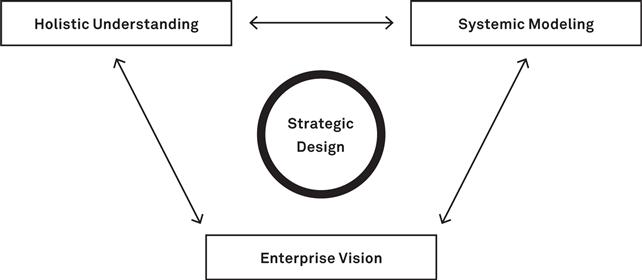

Strategic designers can resort to a set of methods and tools, frequently jumping between different phases of activity:

Holistic Understanding

they spend significant time researching and capturing data, analyzing and contemplating the findings, documenting all that is known about the problem space, reframing the problem in different ways, and making decisions based on that information.

Systemic Modeling

to align viewpoints and bring together different conceptual domains, they use modeling and visualization techniques. They switch between considering the environment outside the core problem, and making different elements work together as an integrated system.

Enterprise Vision

they generate ideas both by querying the environment and assuming that everything could be doable, identifying candidates for a powerful core idea that resonates with enterprise stakeholders, and seek to overcome constraints imposed. The results of this activity tend to look disturbing and provocative to the outside, but can be good starting points for radical innovation.

Design in The Enterprise

Design as a management paradigm, a problem-solving approach, and a professional discipline is a powerful instrument for business leaders. It can help enterprises find sweet spots of value generation in their wider ecosystem by imagining what could be, in an ill-defined and complex environment, and building on that vision to identify and convey a desirable change.

It helps reach out to people important to the enterprise, establish conversations and relationships and expose ways to delight them—as such, it validates and improves the logic of the business towards customers, employees, investors, and other critical stakeholders. It uncovers opportunities for improvement on a level of human experience, informing optimization and restructuring initiatives.

Design can be used as a way to link different viewpoints and domains, and align decisions towards a common vision that is shared and understood. It helps business leaders to break out of the current focus by introducing elements from outside into the organizational strategy. However, this means overcoming the idea of design as an afterthought, by making it a part of the way the enterprise thinks and acts. It requires going beyond the isolated, low-level design commonly practiced today. Design can realize its true value in the enterprise only if applied on a strategic level.

Embedding design in corporate culture

According to business school professors Fred Collopy and Richard Boland in their book Managing as Designing, a fundamental difference in the attitudes of business and design is how they deal with choice. Based on their research into the methods of architects from Gehry & Associates, they describe how those architects relentlessly kept creating new models, designs, concepts, ideas, and prototypes, until reaching a result that they considered to be truly great. They conclude that while the practice and thinking of management assumes the difficulty is in choosing between existing alternatives, design strives to create new and better options to choose from.

This assertion makes the case that to be truly embraced, design has to be positioned as part of the enterprise itself, the shared purpose that drives the activities, decisions, structures, and culture that surfaces in daily business. A culture that fosters a design attitude, that makes everyone involved partly responsible for this quest for the best possible way, to result in remarkable and delightful outcomes. Instead of putting it into another separate function, department, service, or other form of silo, business leaders have to consider design as a pervasive component of decision-making, part of every initiative and operation.

To the enterprise, design has the role of overcoming linear, incremental, and purely analytic approaches by facilitating sensemaking processes and generating new meanings for people. As such, it is used primarily as a source of innovation. An approach on how to leverage design as an enabler of business renewal is Design-Led Innovation.

As a way to achieve innovation, the practice of design in the enterprise cannot be exclusive to design professionals. To get it right, collaboration with design professionals is essential, but as an organizational competency it must be seen as a common mindset and approach, a collection of methods, and a shared experience. It can be applied by trained designers, by other professionals familiar with its essence, and as a paradigm in entire teams and organizations.

To be effective, it needs strong patrons and proponents—hybrid thinkers in connector roles—using it as a strategic instrument. These connectors can be trained designers themselves, or people from other backgrounds integrating design professionals into the enterprise environment, as a studio for business innovation.

Design-led Innovation

Market? What market!

We don’t look at market needs.

We make proposals to people.

Ernesto Gismondi

A prevalent strategic role of design in the enterprise is one of purposeful, systemic innovation. Such an approach to design is described in Roberto Verganti’s book Design- Driven Innovation. Roberto Verganti argues that any technology breakthrough is only the starting point of an innovation. in order to turn that into a business opportunity that changes the game of competition, enterprises have to redefine their meaning in people’s lives, and offer this vision of a new meaning to them as a proposal.

As explored before, innovation can have its roots in many places, triggered by different members of the enterprise, and related to change in different domains. Design processes can be used to explore these places, develop understanding, and engage in a process of prototyping and exchange to generate innovation potential.

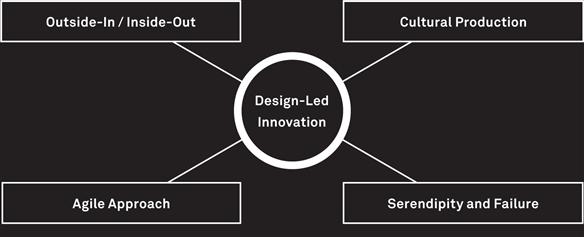

The idea of Design-Led innovation describes the predominant role of design practice in the enterprise. innovation in this sense goes beyond products and services offered to the market to include any kind of transformation that can be explored using design methods.

Innovation that is led by a design attitude can be characterized by certain conditions:

Outside-In, Then Inside-Out

it is driven by the wider enterprise ecosystem, establishing communities with stakeholders acting as sources of inspiration and interpreters of change. Innovation is pursued by proactively envisioning a desirable future state, and offering proposals for new meanings.

Cultural Production

it concentrates on the invention and reinvention of cultural meanings for people, based on the results of a design process exploring the role of proposals as symbols and systems in a socioeconomic structure. As such, it can be characterized as redefining and extending culture.

Serendipity And Failure

it encourages a culture of taking risks and accepting failure as part of the innovation process, exploring new paths as they emerge, and using synthesis to drive the design discourse.

Agile Approach

it strives to get innovations out of heads and committees early, working with prototypes and models instead of abstract definitions, and implementing them iteratively and openly as a shared journey rather than as a planned process.

A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.

Steve Jobs in an interview with Business Week, 1998

Design and strategy as a dialogue

Design as a strategic competency can help organizations to look at themselves from the outside, and transform the enterprise ecosystem from within. It enables business leaders to consider the enterprise in terms of the role it plays in people’s lives, and to (re-)design it to create value for them. Faced with complex relationship challenges, this outside-in approach enables the enterprise to create new and better choices as a basis for better decisions.

To do so, the relationship of design and strategy has to be one of a continuous dialogue. Design has to inform strategy, by providing insights on potential innovations, and generating better options to choose from. Strategy has to be the basis for any vision made visible by design, from initial visual sketches that capture a future state to the redefinition of the enterprise as a modular system. The enterprise becomes a place to iteratively develop and pursue a portfolio of strategies informed and conveyed by design visions, fostering local experimentation and applying good practice to the wider organization. Design connects the enterprise with its cultural environment, and leads a discourse on a meaningful, viable, and feasible future.

This role leads to a new strategic positioning of design in the business, and also requires designers to expand their views beyond the individual products of their work, to all kinds of systems, transitions between system elements, and the big picture of the enterprise. It requires both design professionals and the business leaders working with them to take a step back and look at the enterprise in the context of its wider ecosystem, as a shape visible to all stakeholders.

Part 2 of Intersection introduces a common language for people involved in strategic design, capturing the enterprise as both the context of any design initiative and as the subject of its results.

AT A GLANCE

Using design as an approach to key business challenges enables enterprises to intentionally change the way they relate to people. As a strategic competency, it helps to bridge silos, capture relevant aspects, and synthesize a human-centric vision of the future.

Recommendations

Use design as a competency to develop a deep understanding people your enterprise addresses, and to develop and test responses to wicked key challenges

Instead of putting this competency in another silo, apply it as the linking force between the contributors to strategy and its implementation

Establish a continuous dialogue of interpretation and local experimentation between strategists, designers, and the enterprise ecosystem

Use an enterprise-wide design approach to drive change initiatives resulting in human-centric innovation as the focal point of your business strategy

Case Study _ Apple

Apple’s Enterprise

Creating integrated ecosystems of devices, content and platforms, for remarkable experiences in people’s private and professional lives.

Businesses around the world look at Apple as the shining example of a design-led enterprise, and the company as the subject of a lot of conversations and articles on that topic. On the other hand, not too much is known about the way the company really works on the inside, and how they address the challenges of integrating design practice into a fast-paced business environment. This case study pulls together what is has been revealed about design at Apple, and looks to summarize key insights of the role, culture, and organization of design practice in that company.

One particular observation made by various commentators both inside and outside the company is the remarkable perception and culture of design, which can be considered a significant part of Apple’s DNA. This goes well beyond an understanding of design as a function of Marketing, Product Management, or Communication. Championed by Steve Jobs until his death in 2011, Apple designed its own market instead of preparing for changing external conditions. By deliberately making huge leaps into the future and experimenting with potential shapes of their enterprise, they were able to make those states visible.

We believe that applying design strategically enabled Apple to draw a picture of their future that everyone involved could work towards, a shared idea about their enterprise. Therefore, they integrated design into their thinking and doing at a level only few other organizations do today.

In most people’s vocabularies, design means veneer. But to me, nothing could be further from the meaning of design.

Design is the fundamental soul of a man-made creation that ends up expressing itself in successive outer layers.

Steve Jobs in an interview with Fortune Magazine, 2000

Designing An End-To-End System

Looking at the offerings Apple has put on the market since Steve Jobs returned to lead the company in 1997, its expansion into new market segments and industries is simply stunning. From being a computer manufacturer, Apple made its way into the areas of consumer electronics, communication, entertainment, and business solutions, becoming the world’s most profitable business.

In this setting, the role of design has been a critical enabler for the whole enterprise. Starting with the users they made their products for, Apple naturally expanded their business into areas adjacent to their current business focus. Unlike expansion strategies of other companies of comparable size, such quests into new territories were not done in isolation from the current products, assets, and markets. Instead, every new offering Apple introduced was a logical extension of the portfolio, delivering another key part of the system. From computers to music players, from players to phones and tablets, from devices to content, from stores to cloud services—all these things are part of one platform, and contribute to one vision.

Design as practiced at Apple delivers both the insights and visions to conceive that system, starting at the user and step by step winning a larger part of their world. This involves experimenting with different materials, technology, and modes of customer interaction—the classic playing field of traditional design disciplines. But more than that, it also means designing new distribution channels, content structures, business models, system architectures, and other conceptual parts of the system. Instead of concentrating on one segment and neglecting the others, Apple’s design approach enables systematic growth.

Design as a Culture

Insights about Apple’s corporate culture are largely based on anecdotal references. However, certain elements are emphasized repeatedly by various sources, and make the case that they approach product development more like a fine arts workshop than a classic industrial setting. Key to this is a sense of authorship, implying that there is one single, coherent vision about the final result of a design process and the way it should appear in people’s lives. At Apple, this vision is part of the responsibilities of senior executives up to the CEO level, including the task to prevent any deviation or expansion that does not contribute to its achievement.

As a design-oriented company, many of the technologies and ideas Apple puts into implementing a vision come from somewhere else, and the company made a series of acquisitions to support that. In the end, however, all those parts fit seamlessly into one designed system, with a great appreciation for perfection in concept and execution. This requires bridging a lot of different viewpoints, be it different domains such as Marketing, Engineering, and Design, but also people from companies taken over, and different actors in Apple’s ecosystem.

A core element of such an alignment effort is a strong attitude that drives the way an offering is envisioned and designed. Many observers stress the relentless quest for perfection, the constant reduction to the most essential. This also involves the hard work of refining every detail again and again in the service of the user, constantly questioning if something can be even better. Regardless of what part someone contributes to, this holds true for the work of teams in Experience Design, Software Development, and Mechanical Engineering.

Everything at Apple can be best understood through the lens of designing. Whether it’s designing the look and feel of the user experience, or the industrial design, or the system design and even things like how the boards were laid out.

The user experience has to go through the whole end-to-end system, whether it’s desktop publishing or iTunes. It is all part of the end-to-end system. It is also the manufacturing. The supply chain. The marketing. The stores.

John Sculley, former Apple CEO (Source: cultofmac.com)

We struggle with the right words to describe the design process at Apple, but it is very much about designing and prototyping and making. When you separate those, I think the final result suffers.

Jonathan Ive, Senior Vice President, Industrial Design at Apple (Source: thisislondon.co.uk)

Apple’s product releases attract large crowds

Finally, Apple’s culture seems to thrive on ideas. In his tribute to Steve Jobs, Jonathan Ive praised the way Apple’s leader recognized that even the boldest and most powerful ideas begin their lives as fragile entities, so easily lost in a process of compromise, groupthink, and reinterpretation. Apple excels at making ideas fly, the very essence of design work.

Design As An Organization

Although there is a lot to learn from good examples, we usually tell our clients at eda.c that there is no point in trying to be Apple (or SAP, Google, Facebook or Microsoft for that matter). In our experience, every successful enterprise is a unique entity. Organizations are certainly able to learn from role models, but they risk losing their core idea and unique identity when mindlessly incorporating elements from others.

One of the stories worth exploring for any enterprise is how Apple formally made design part of their organizational structures and business practice. Although the cultural basis and the systemic approach both are necessary ingredients of the way Apple embraces design, these elements seem to incorporate the underlying attitude into operational processes, reporting lines, and project work.

Apple’s design group benefits from a direct reporting line to the CEO, giving design professionals a powerful position in the organization. What comes out of a design process is therefore part of the company’s strategic direction, being the result of a dialogue between strategy and design to put that vision into a visible picture. This is radically different from most companies even in the same market segments as Apple, and a way to systematically circumvent design-by- committee, where too many people insist on including their own wish list.

To bridge the vision with the feasible, Apple puts a design concept into implementation even before a clear target state has been defined. In an interview for Technology Review, Apple’s former Industrial Design chief Robert Brunner indicated that Apple sends teams of designers into factories sometimes for periods of weeks, pushing manufacturers to find new solutions and making technical decisions together. This expands the design task and the ownership to actors outside the boundaries of Apple’s organization, and enables the joint experimenting and product making that is behind the company’s remarkable products and services.