8

Rendering

The range of aspects described in the previous chapters is meant to help a multidisciplinary team consider the intangible dimensions of strategic design work. Thoughts about suitable interactions, the organization of information, the business model or domain structures behind a certain solution, questions of brand identity or the choice of actors to address — all these elements lay the foundation for making informed design decisions and drawing a picture of the future. When working on a project meant to have strategic significance for an organization, project teams are often tempted to keep the design process on an abstract level for quite some time. The diversity of stakeholders and concerns, and the mass of questions posed and thoughts being exchanged make it easy to lose yourself in high level decisions while avoiding the concrete—this is often visible in team discussions about abstract concepts such as customer loyalty or brand values. To become reality, any design process needs to turn this abstract foundation into concrete results that have a determinate impact on people’s lives.

Design is always about making, and as such it is a craft that requires us to work with materials, production techniques, and creative expression, mastering their usage and effects. Every decision made, conceptual model applied, or transformation intended that comes out of a design process must eventually result in something visible and tangible in order to come to life. Using design strategically in the enterprise does not imply abandoning this form-giving process that differentiates a design approach from a purely intellectual planning exercise. Although it starts on a conceptual level deeply grounded in strategic thinking, research activities, and systematic modeling, it is the concrete results that count.

The Enterprise Design framework is about defining and shaping these results as a web of connected elements rather than as isolated artifacts, and designing them to play a certain role in the enterprise as a bigger system. Conceptual aspects form the basis for deciding what to make in order to achieve what effect. The three remaining aspects of the framework portrayed in this chapter are about bringing them together and giving them a form as parts of a desired future state of the enterprise.

Visible futures

The way we perceive the world and interact with it is largely driven by our nature as embodied physical beings. The environments that surround us and the objects we use are so closely connected to our thinking and behavior that we make use of them to arrange and structure our lives. Every morning, we move from the bedroom to the bathroom, go to work, come home again later on, and using physical environments to organize our activities. We "have a glass of good wine" together with some friends, we collect souvenirs from our vacation trips to help us remember, we associate sensations picked up from our environment with memories, places, or activities.

Physical objects or places and their configurations serve us as focal points to help make sense of the world, as symbols and contexts for our thinking and acting. We use physical metaphors such as "rising stock prices" or "going into a project phase" to describe entirely non-physical things. This universal role of physical categories is also visible in the way we apply them to activities within digital environments, where we are opening and closing application windows, moving around on the web, or "poking" someone on Facebook without leaving our computer, illustrating how the physical world rules our increasingly virtual lives. The continuing digitization of our environment makes us constantly shift between the virtual and the physical even when dealing with a single artifact.

Being an intangible conceptual construct, the enterprise comes to life only in real-life situations, as its substantial manifestation. Any intended transformation requires a translation into a set of concrete elements to be designed, produced, and introduced, turning the underlying intangible concept into perceivable signs, tangible things, and habitable places. As strategic design initiatives by definition have to start without a predefined outcome in mind, the choice of what concrete results to produce, and what shape they should assume fully rely on the ideas of the team members and the possibilities at hand. Each conceptual aspect previously described can be taken into account as an external reference to develop this set of outcomes.

One of the particular strengths of a design approach to difficult challenges is its inherent emphasis on crafting visible results that are fully controlled and envisioned by the designer who creates them. As part of this framework, we suggest three aspects to pave the way from strategic thinking to the crafted outcomes of a design process:

Signs

![]() are carriers of messages and symbols that people are exposed to. The enterprise and its actors produce and place signs, but to make them perceivable they have to be encoded media of some kind, such as written words, visual or auditory messages. signs are generally created to reach a specific audience with a certain effect in mind, such as making a message heard, enabling understanding through communication, conveying an identity, or supporting wayfinding.

are carriers of messages and symbols that people are exposed to. The enterprise and its actors produce and place signs, but to make them perceivable they have to be encoded media of some kind, such as written words, visual or auditory messages. signs are generally created to reach a specific audience with a certain effect in mind, such as making a message heard, enabling understanding through communication, conveying an identity, or supporting wayfinding.

Things

![]() are objects people use, own, consume, take with them, or create. In the context of design, the term refers to various kinds of man-made artifacts such as goods, devices, and tools. In the enterprise context, there is a mass of things being produced, utilized, and exchanged. designing things, thereby defining shape, characteristics, and materials, has the goal of supporting usage or marketization.

are objects people use, own, consume, take with them, or create. In the context of design, the term refers to various kinds of man-made artifacts such as goods, devices, and tools. In the enterprise context, there is a mass of things being produced, utilized, and exchanged. designing things, thereby defining shape, characteristics, and materials, has the goal of supporting usage or marketization.

Places

![]() are where people go, where they live or stay, meet or work. They provide the environments for activities and interactions in the enterprise, but at the same time they are also the stimuli for personal associations, memories and moods, as well as social connotations. designing places means generating context for people by shaping their surroundings.

are where people go, where they live or stay, meet or work. They provide the environments for activities and interactions in the enterprise, but at the same time they are also the stimuli for personal associations, memories and moods, as well as social connotations. designing places means generating context for people by shaping their surroundings.

The aspects described in this chapter are meant to support the choice of outcomes, and employ the large variety of the arts, and classic fields of design, to make them reality. They are about giving enterprise elements a form—for example, as interiors, websites, pieces of software, print media, or signage, and making these elements work together as a system. Because of the large field of design disciplines, the practices portrayed are archetypes for individual design expertise to be called in. Depending on what best translates your vision of a future enterprise into action, you might need to involve web or mobile app designers, interior or landscape architects, or a mix of editors and illustrators, just to name a few.

The conceptual background based on the previously described aspects is the basis for working with specialist designers, envisioning the outcomes of a strategic design project. Nevertheless, it provides just the intellectual framework to guide the creative process. At this level, the myriad of strategic considerations and conceptual decisions essentially becomes a checklist for a designer to consider when coming up with a design proposal. The center of attention then shifts to a mastery of the selected creative domain and the tiny details of the design.

Bringing a strategic design initiative to a state of tangible outcomes can prove quite challenging, especially since these activities are traditionally considered to be merely tasks to be executed. They are often relegated to the lowest organizational level or carelessly left to external service providers. In reality, these outcomes are the only bridge connecting a strategic design project to the results it seeks to achieve. Neglecting their importance risks spoiling everything, and even the best conceptual approach will not help if the details of the outcomes are badly designed.

To be effective, the crafted outcomes have to embody all conceptual decisions and turn them into perceivable qualities and usable functions, to trigger a transformation of the enterprise as a system. This is exactly what distinguishes mere reactive beautification from a strategic design approach. The challenge therefore lies in turning the concrete outcomes into a rendering of a strong concept about the enterprise, and achieving the translation from thinking to creating while preserving excellence in creative work and professional craftsmanship.

#18 Signs

The term signs in the context of this framework refers to all kinds of messages encoded in visual display devices or other types of media, created to convey a message to someone in the enterprise. Being an important part of our culture, signs and symbols permit recognition, convey information and meaning, enable wayfinding and usage of machines, trigger complex chains of thoughts, and cause profound emotional reactions. They can be used as a common communication device based on associations shared between people, making a message speak on different levels of the dialogue. Consequently, the creation and use of signs and symbols is the most straightforward way to make connections between an enterprise and its audiences.

Signs can be seen as individual interpretations of a set of impressions to our senses, for example, a pattern of colors that is picked up by the eye. The subsequent processing in our brain then enables us to recognize shapes and figures, distinguish figures from their background, and to make all of these interpretations the subject of our recognition and thinking processes, making up our minds about what a sign stands for and what it means to us.

Considering this process, although it happens quite quickly and on an unconscious level, is the basis to make use of signs in a way that they direct people’s attention and have an actual impact. Anything being made in the enterprise can be seen as a contribution to a dynamic exchange of signs being created and perceived. The shapes and configurations of these signs drive the interactions with people. Because this is the perceivable part of the enterprise, it has to be addressed as one of the key aspects pertaining to the rendered results of strategic design initiatives.

Signs as a subject of strategic design

The world is flooded with man-made systems of signs. The process of producing signs is continuously happening and accelerating, with everyone being able to participate. At the same time, there is a steadily growing number of different media transporting these signs to their audiences. Road signs share the urban space with advertisements and street art, while print and broadcast media is used in various formats to inform and educate, and tell stories in books, magazines, radio messages, and other forms of media. The Internet and interactive forms of media add to the mass, so all these channels intersect and converge and make users constantly transition between them.

Instead of disappearing completely, legacy media often just exists alongside the new media — for extended periods of time such as newspapers, or in a niche like vinyl discs. Today, it becomes clearer that although the digital revolution has hit the media landscape with all its force, the paperless world is still far away, if ever to arrive. Paper-based media like books, magazines, and office paper still prevail. Other than shortcomings of display devices, there is something special about paper as a medium, a sensation-filled experience of haptic qualities, smell, and usage that makes it difficult to substitute.

In the context of strategic design work, this translates to the challenge of dealing with an intermingled mass of media. Virtually all organizations make extensive use of such systems to encode and deliver messages to their stakeholders, in the form of advertising, email messages, websites, packaging, stationery, or signage on their campuses. More often than not, organizations deal with signs in a limited and chaotic way, applying a set of visual brand elements just to their official mass communications for external target groups, while leaving their other roles, aspects, and audiences to chance. Such a superficial approach neglects the true significance of signs for the enterprise, as carriers for making meaningful impressions on people and to facilitate exchange and interaction.

Example

As an example for signs used ubiquitously across different purposes, consider a national flag. Depending on the context of use, they indicate the country where a car is registered, an embassy in a foreign country, but may also be used by hotels to decorate their entrance in an "international" fashion. On a pragmatic level, flags are also often used to depict a language on websites or in restaurant menus, despite all the ambiguity there is in such representations. Beyond these specific purposes, flags are highly iconic symbols loaded with a wide range of interpretations, visible in the UK’s Union Flag used in pop culture, or when people enthusiastically wave specific flags in street demonstrations—or burn them instead.

To be strategically relevant, systems of signs have to be designed according to the enterprise environment they seek to support — making them take up their role to get relevant messages across, thereby underpinning the enterprise. A design team has to consider all suitable media channels to shape a system of signs that makes the enterprise in all its facets visible to the actors it is addressing.

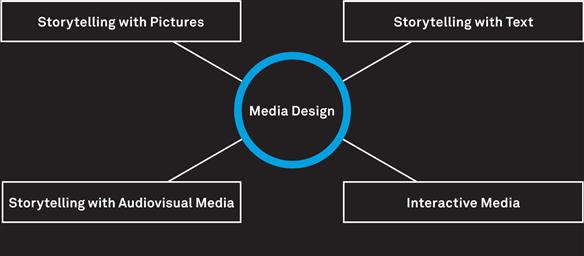

Media Design

Media Design in this context is in fact an umbrella term, used mainly in European countries to describe a dynamic field of specialized design disciplines, all with dealing the design and production of some sort of media. The field is also often called communication design or visual communication, all referring to slightly different aspects of the same task, which consists of giving a form to messages the to be conveyed to a targeted audience using a specific medium such as paper or the web.

Because of their shared roots, this area overlaps with the fine arts, having similar means but different purposes in mind. when talking about media and design, there is traditionally an implied emphasis on creative practice addressing visual perception, such as in graphic design or photography. Applying a broader view, the field today presents itself with a large variety disciplines and sub-disciplines with varying degrees of specialization.

the professional use of media for the purposes of strategic design depends on the collaboration of expert designers from these different fields. it might also involve other disciplines such as musicians or artists, or be completely independent of a recording technology, as in the case of a live performance for events. but more importantly, it has to be based on the larger vision of the enterprise and the way it uses media to make that vision happen, and encode its messages effectively into perceivable and significant systems of signs.

The fields of media design boil down to the creation of narratives using different media devices:

STORYTELLING WITH PICTURES

this area is about disciplines concerned with the creation of visuals, such as Graphic Design, Photography, and Illustration. Visual signs are often used as a universal language, to evoke cultural associations, generate attention, or make an emotional impression. They are the basis for printed publications, interactive interfaces, and web media, as well as iconographic signage systems.

STORYTELLING WITH TEXT

design of text-based media consists of two related aspects, the authoring and the communication of textual content. Like graphics, text is part of virtually any medium, and regroups disciplines such as Copywriting and Editing. Textual signs can be produced as for visual media requiring Typography and Layout work, or for reading out loud in an acoustic medium.

STORYTELLING WITH AUDIOVISUAL MEDIA

disciplines dealing with moving images and sound, such as Film, Sound Design, Motion Design, and Animation. Depending on the selected medium, the professional creation and production of these types of media involves a wide range of designers and other practitioners such as the performing arts.

INTERACTIVE MEDIA

are yet the most advanced form of media, mixing all three forms with interaction and behavior.

Signs In The Enterprise

IDENTITY

![]() manifesting a chosen brand in signs as a perceivable identity, such as a logo, appearance, sounds, and smells.

manifesting a chosen brand in signs as a perceivable identity, such as a logo, appearance, sounds, and smells.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() using systems of signs that make the enterprise work, as in instructions, notifications, or news updates.

using systems of signs that make the enterprise work, as in instructions, notifications, or news updates.

EXPERIENCE

![]() making signs meaningful to people in terms of language, tone of voice, and message conveyed, like in a personal letter.

making signs meaningful to people in terms of language, tone of voice, and message conveyed, like in a personal letter.

ACTORS

![]() adapting signs to the nature of the relationship, engaging investors and convincing partners or customers.

adapting signs to the nature of the relationship, engaging investors and convincing partners or customers.

TOUCHPOINTS

![]() choosing the right signs for a given context, such as a mobile app to take with you, a display for wayfinding, or a movie.

choosing the right signs for a given context, such as a mobile app to take with you, a display for wayfinding, or a movie.

SERVICES

![]() making signs support and facilitate services, for example, what call-center staff members tell you about an offering.

making signs support and facilitate services, for example, what call-center staff members tell you about an offering.

CONTENT

![]() turning content into narratives and chains of signs, like a commercial proposal or by introducing a behavioral code.

turning content into narratives and chains of signs, like a commercial proposal or by introducing a behavioral code.

making signs support business goals, informing decision makers about what’s happening or placing up-selling offerings.![]()

PEOPLE

adapting signs to the audience it is intended for, such as Braille or advertising for a specific profession.![]()

FUNCTION

shaping the signs so that it fulfills its purpose, like using visualizations to enable decision making.![]()

STRUCTURE

representing the subjects the sign is referring to, using consistent wording or providing accurate illustrations.![]()

COMMUNICATION

using signs to convey a message and support the respective communication modes, like polls to foster participation.![]()

INFORMATION

placing signs to make information accessible and support understanding, such as icons for recurring categories.![]()

INTERACTION

shaping signs to trigger behaviors and engage people to act, like an audio warning signal.![]()

OPERATIONS

shaping signs to support business activities and enable operations such as a roadsign or a car plate.![]()

ORGANIZATION

designing signs to support team collaboration, for example, an Employee of the Month initiative.![]()

TECHNOLOGY

placing signs using media technologies and techniques such as projection or mobile devices.![]()

Sign systems for enterprise rhetoric

Too often, design projects are initiated with a specific target medium predefined by a commissioning party, directly addressing specialist designers such as web or motion design agencies. Applying the conceptual aspects portrayed in the previous chapters permits us to rephrase a complex enterprise-design problem as a design challenge, and to conceptualize solution approaches on a level that is initially agnostic to whatever concrete media might be used. This puts a design team in a position to question these preconceptions, and to determine suitable target media in the course of the project. Envisioning a system of signs and media in terms of its role in the enterprise makes a large part of the design decisions a logical consequence of the underlying concept.

Shaping messages into systems of signs in context of an enterprise can be seen as telling a story to its audiences. Depending on the individual purpose of the signs and the context wherein they are used, different aspects of the enterprise come into play and have to be brought together in a coherent way, such as concerns of security and operational safety, sales and Marketing, knowledge and intelligence. All of these messages are part of the same story about the enterprise, and enable its various actors to see themselves in it, define their role, commit, and participate.

In written or spoken language, the art of using words to inform, persuade, or motivate an audience is known as rhetoric. Just as speakers turn their discourse into a considerate flow of statements and figures, a system of signs arranges elements in a way that they effectively work together to convey the message. The task of design in that regard is to define these elements and rules for their application. It is the rhetoric of the enterprise, exposing some parts while hiding others, directing attention, and getting its story across.

Example

Think of a corporate intranet as the primary workplace environment of employees. It is used as a medium to deliver a wide range of messages to its audiences, from product and sales information to self-service offerings and work-related tools, regulations, and critical safety information. Creating a system of signs that guides the attention of intranet users to the most relevant parts is a challenging task, also because it is often a tool that is highly disputed between different departments such as Communications, IT, and HR. Applying the conceptual aspects will help to define the key stories the intranet should convey, and turning them into a system to encode messages, present information, and guide user choices. Instead of decoration and ornamentation or running after visual trends, a thoughtful application of typography, signs, and space can visually convey its essence without distraction.

The extensive work with the conceptual aspects of the Enterprise Design framework predefines the story to be told, and how to tell it effectively. It is the basis for defining a vocabulary of signs to encode it in media, making the rules and relationships between them transparent. The logic applied to that system and its components should not be arbitrary, but motivated from the underlying rhetoric, and turned into decipherable messages both visually and by other means.

While this translation is a key step of strategic design, it is not the whole story — as good design lives off of good ideas, it is often external inspiration and the work of experienced and talented craftspeople that turns a solid design job into a great one. The goal of working in a systematic fashion is not to find a reason for everything, but to generate options that combine the rational with the inspired.

#19 Things

We have always been cyborgs

Michael Shanks, Stanford University

Organizations and individuals make, buy, sell, and use things as part of their activities. Such things are most commonly industrially created objects for usage and consumption. The practice of design applied to things encompasses a wide range of different objects being subjected to a creative process, from toys and household appliances, tools, and furniture made for private consumption, to industrial appliances, machines, or software applications being used as invested assets in organizations, with a great deal of overlap between those areas. Most objects we use in our daily lives are so embedded in our activities that we often don’t even notice they are there. Of course watching TV requires the possession of or access to a TV set, but also more profound human needs rely heavily on objects — we sleep in beds, write with pens, read books, and call people with phones. There are numerous examples where the activity is called after the tool or device used to perform it, such as in vacuuming or (more recently) googling the web.

In the fields of archeology and anthropology, artifacts recovered from excavations are examined as objects of cultural relevance. They deliver insight into the way people lived, how they performed daily activities or individual tasks, and allow us to draw conclusions about the cultural particularities of extinct civilizations and human life in former times. These insights in turn can be used to recreate their experiences and habits — making sense of the intangible by studying the material evidence in the light of history. In his research, archeologist Michael Shanks from Stanford University makes the case that this evidence, the things we use in our lives, cannot be separated from our nature. Objects and artificial extensions to our bodies are an intrinsic part of human existence, issued from a joint evolution of the natural and the artificial — we shape our tools as much as our tools shape us.

In a similar way, contemporary artifacts being designed, produced, and used today have to be regarded in terms of their role as extensions of ourselves, applied in a certain cultural context. They are made to be a part of everyday reality, with their shape, characteristics, and functions designed to contribute to our existence in a meaningful fashion. Designing things should reflect their role as cultural artifacts for the people addressed by the enterprise.

Designing things as enterprise artifacts

Organizations produce and use things for a large variety of reasons and purposes. A large part of the economy involves creating and selling things, such as cars or other machines, manufactured products like clothing or food. In these product- led industries, design and related disciplines are used to create the products that are offered to the market, being seen as a part of the product development cycle. As a function applied to the value chain of the organization, the role of design is to translate the aspects of use and the symbolic character of the brand into a form suitable for production.

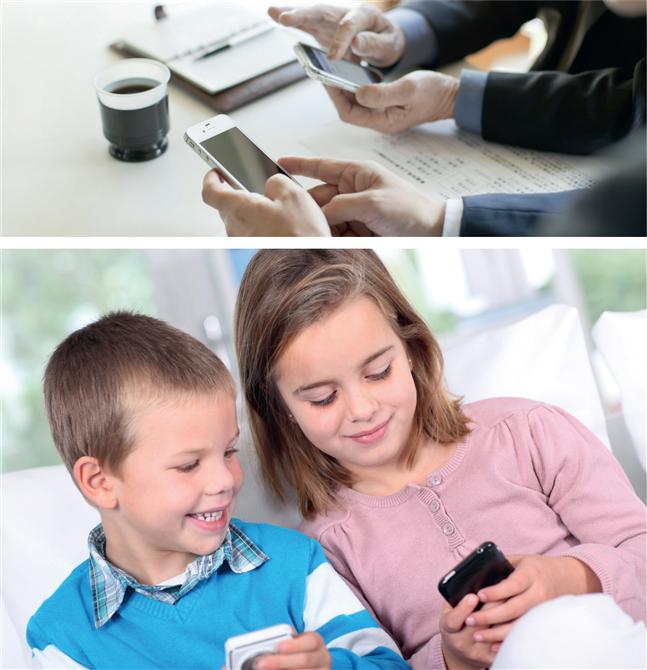

Because of the continuing digitization of various types of products, product designers today often need to address physical materials together with software components and interfaces as part of the same product, with an increasing significance of its digital parts.

Example

The task of designing a cell phone has changed significantly within the past decades. Originally a task of bringing together ergonomics and aesthetics applied to mechanical artifacts, recent generations of phones are closer to computer platforms than they resemble their predecessors. The task of the designer has shifted from defining the form of a physical thing to defining the interface and behavior of its screen contents and other channels, amplifying the need for Interaction Design and Information Architecture specialists. Moreover, the phone has become an open platform for apps (essentially virtual tools or things), enabling organizations to address specific needs in a design tailored to their audiences — including customers, employees, or others.

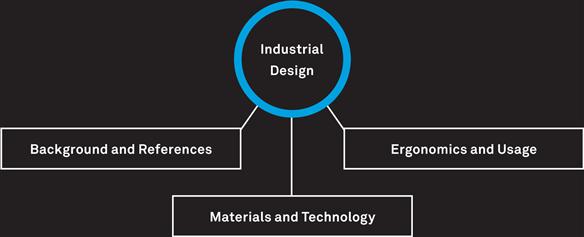

Industrial Design

The professional field of design applied to things for serial production is known as Industrial or Product Design. The practice is about shaping the form of a physical object with regards to its use and its meaning for people. There is a wide spectrum of branches and specialized disciplines within the field, applying the practice of design to fashion, furniture, cars, electronic devices, or industrial machines.

As in the other traditional fields of design, Industrial Design deals increasingly with things that use software components to a large degree, turning the attention of design from the outer form to the design of interface elements and their behavior. Examples of considerate Industrial Design achieve a symbiosis of the physical and the virtual elements of a product, designing for the User Experience as a whole.

The field of Industrial Design is probably the best known domain of design, being also the area of many notable designers. In professional practice, however, the task of envisioning, designing, and delivering a product is the result of interdisciplinary teamwork involving many different areas of expertise and the mastery of professional tools. This effort pays off handsomely, given the ubiquitous role tools and other things are playing in our professional and private lives. Their characteristics and shapes are a key element in any desired change.

The task of coming up with a solution requires balancing different considerations to be taken into account to define a suitable form:

BACKGROUND AND REFERENCES

designing a product to express the goals and values behind its creation, also sometimes referred to as the styling of a product. This aspect can be defined as the embedding of references into the form. such references can be based on the personality of a famous designer, on the brand identity of the company offering it, or the culture and context of use it is made for.

ERGONOMICS AND USAGE

working on the relationship between an object and its user, and adapting the form to the activities that it is supposed to support. This refers to the functional character of a product, choosing its form based on the tasks and needs of people, their characteristics and abilities. The designer might also enhance the product’s functions or combine functions that go well together.

MATERIALS AND TECHNOLOGY

considering technology, raw materials, and engineered solutions as part of the design process is an intrinsic part of the industrial design discipline. This is especially true in technology-centric industries, where design is employed to make technical innovations accessible in a product. In the context of physical things, this involves making materials, technical components, and manufacturing considerations a part of the design process.

Things In The Enterprise

IDENTITY

![]() designing things as symbols representing identities and their characteristics, such as luxury furniture in a hotel lobby.

designing things as symbols representing identities and their characteristics, such as luxury furniture in a hotel lobby.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() designing artifacts adapted to their role in the enterprise, like a handheld device for an operative job.

designing artifacts adapted to their role in the enterprise, like a handheld device for an operative job.

EXPERIENCE

![]() shaping artifacts according to their meaning for people, for example, a tool to help you wake up more easily.

shaping artifacts according to their meaning for people, for example, a tool to help you wake up more easily.

ACTORS

![]() designing things to support a specific relationship to the enterprise, like an employee access card.

designing things to support a specific relationship to the enterprise, like an employee access card.

TOUCHPOINTS

![]() designing artifacts according to the context in which they are used, such as mobile devices suited for postal service.

designing artifacts according to the context in which they are used, such as mobile devices suited for postal service.

SERVICES

![]() designing things to make a service run, such as a kitchen bell or a self-service kiosk.

designing things to make a service run, such as a kitchen bell or a self-service kiosk.

CONTENT

![]() designing things to make useful content available and enable exchange, like the starter pack for a new bank account.

designing things to make useful content available and enable exchange, like the starter pack for a new bank account.

BUSINESS

designing things to match and support a business model, for example selling a cheap device with profitable consumables.![]()

PEOPLE

designing things to adapt to people’s characteristics, like a cell phone that matches the needs of kids.![]()

FUNCTION

designing things to fulfill a need or requirement according to a defined purpose, like a dentist chair.![]()

STRUCTURE

designing things to enhance and fit into a given structure of related objects, such as a jet bridge connecting gate and airplane.![]()

COMMUNICATION

designing things to facilitate communication processes and social exchange, like furniture for work in small groups.![]()

INFORMATION

designing artifacts to convey information related to their usage, such as labels on a stereo.![]()

INTERACTION

designing things to support and convey a range of defined interaction possibilities, like a touch screen or a knob.![]()

OPERATIONS

designing artifacts to facilitate operations in the enterprise, such as a device for train conductors.![]()

ORGANIZATION

designing things to play a certain role in organizational reality, such as the water cooler as a meeting point.![]()

TECHNOLOGY

designing things to make technology accessible and usable, for example, a user interface for a complex business application.![]()

Designing things, both in the physical and the virtual sense, is not limited to the design of salable products. Even if not directly sold, things are a part of any offering made to the market, and of all processes or services carried out in the enterprise. In any given context, things are being made or employed to carry out tasks and support interactions between people. As cultural artifacts of the enterprise, things are focal points to support and engage people, so their design should be subject to initiatives that aim at a holistic transformation. By designing things that are meaningful to people as a result of a strategic design process, we can purposefully transform the activities, habits, and practices of enterprise actors to support the underlying strategy and conceptual thinking.

Using things in the enterprise

Things have multiple roles and meanings in the enterprise — as cultural artifacts, as tools to support human activities, as products to be offered to the market, or as an interface for service provision or process execution. Redesigning these components of the enterprise in a way means redesigning the enterprise. The conceptual aspects deliver the background needed to inform a thoughtful and holistic Industrial Design process. They bring clarity to questions of function and usage, references and goals, as well as technical possibilities and constraints.

Designing things is at the core of the design disciplines. While the focus of the field is moving towards achieving strategic transformation through a design approach, the products resulting from a design process are the focal point for such a transformation to happen.

Nick Marsh, Design Director at the UK design consultancy Sidekick, wrote about such a product-centered approach to design in his blog. He uses the term New Product to describe a new generation of networked products that bring together the physical and the digital in a way that sparks great experiences for their users. These products make interactions with the web and live data exchange a part of their characteristics, while still considering the physical context of their usage as a key factor in the design process.

When people talk about the New Product they’re generally describing businesses that provide a mix of content, service and experience. But the way they make that tangible is by focusing on product.

Nick Marsh (choosenick.com)

Putting the emphasis of the design process on the things to be made helps a design team to adopt the solution-oriented mindset that is critical in design work. While the objective of achieving and sustaining a lasting change that has an impact on the enterprise prevails, focusing on the making of things allows us to turn ideas into a tangible form. We can bring together strategic thinking and conceptual aspects in real objects, ready for experimentation and prototyping, validation, and iteration. This immersion into the physical use context of an object allows the design work to focus on illustrating conceptual decisions through their implications for the things to be created.

For companies that make and sell things, designing their products is obviously the most relevant use of design—but also in other industries, designing things matters. Expanding on the role of things in the enterprise, as operational tools and cultural artifacts, their design can be defined as the creation of boundary objects to trigger and sustain a transformation to a desired target state. For the enterprise as a web of things, this translates to an active consideration of product design for all actors to be addressed, and taking form factors into account when deciding what to build or buy to make things a part of commercial offerings and business operations.

#20 Places

The last aspect of the Enterprise Design framework is about the environments used in the enterprise to facilitate activities and interactions among actors. Organizations are designing places and use real estate for various purposes. In fact, the way physical space is organized is a critical factor in many organizations of the service sectors such as hotels and restaurants, where the facilities offered and the ambiance created are parts of the differentiation to the market.

Some businesses require a network of local stores to get near their customers, while others just work with offices and warehouses. Others again perform their activities in environments made available by other actors in the enterprise, such as market spaces or customer sites. Depending on the respective industry background and chosen business model, there are many different concerns being addressed with such structures, requiring different kinds of spaces for different purposes. Production plants are designed to support the operational flows, and strive for the most effective use of space. By contrast, corporate headquarters and environments for customer interaction are designed with representation and persuasion in mind.

Seen as infrastructure of the enterprise, spaces are created or used to bring people together. They support teams that collaborate, service staff that interact with customers, or other actors engaging in some sort of interaction. In such cases, the physical surroundings have to support the sometimes divergent needs of different actors, and provide adequate facilities for their interactions. Basic environmental factors like the floor plan, the temperature, and acoustics are mixed with questions of furniture and equipment, style, and interior design.

The ongoing shifts in the way we live and work also bring a change in the way people and organizations make use of real estate in general. While the meaning of buildings shifts towards external communication and operations of a physical nature, more and more of what is happening in an enterprise is moving to virtual spaces.

Tasks that required consumers to visit stores or markets are now performed using digital channels, such as shopping for books or opening a savings account. People are no longer required to be in an office to do their jobs, especially those performing a function dealing with information and communication. For such tasks, digital platforms and devices to access them serve as equivalents to the physical places that used to fulfill a similar purpose.

This does not mean that people are no longer leaving their homes, but that the virtual and the physical spaces overlap and form a blended spatial construct. Every virtual space can only be used when embedded into the physical space the user is accessing it from—think of tablet devices often used to surf the web in a lean back situation, sitting on a couch.

Designing where the enterprise happens

Whatever task people do in the context of an enterprise relationship, they do it in some environment — at their office desk, on a train, on the couch at home, or in a café. Each of these physical contexts imposes an environment for our activities, with certain possibilities and limitations — their effects on our lives are obvious, ranging from ideal environments such as an inspiring busy café to a loud railway station spoiling a customer call. Given the complexity of owned and shared spaces, the varying degree of influence on physical spaces and their virtual extensions, and the new freedom of taking places with you, dealing with space as a domain for design is a challenging task for organizations.

Example

Many jobs today are not bound to a certain location the way they used to be. As an example, imagine the activities of a lawyer—consultations with clients to discuss cases, going into court for the actual oral argument before a judge or jury. Connected by digital media and devices, there are several tasks that can be done from anywhere in theory, such as researching law texts, drafting court papers or contracts, and even communication with clients or experts. Activities that required traveling or dealing with large amounts of documents on paper now are done by going to virtual places, which allow pulling out information into different physical contexts whenever it is required.

Designing space for the enterprise is essentially about providing suitable contexts for everything happening as part of the activities being performed in its realm. To make the aspect of space accessible for the purposes of design, it must be viewed in terms of how people use and experience it, rather than a geometrical entity or abstract infrastructure.

A key concept of how people deal with their environment is the notion of place, a subjective and personal idea of where we go and why. A place entails subjective notions of purpose, memories or emotions, and can be distinguished from the objective and rather detached concept of space. Adopted by professional architects in the last few decades, place differs from space in that it is about what a certain location and situation means to someone, and how to design spaces to become places where people go to spend their time. In their book Pervasive Information Architecture, Andrea Resmini and Luca Rosati describe the heuristic of Place-Making as laying the foundation for being there —the capability to help users reduce disorientation, build a sense of place, and increase legibility and way-finding across digital, physical, and cross-channel environments.

When you focus on place, you do everything differently.

The Project for Public Spaces

When thinking about our favorite places, it becomes clear that it is not about space alone. The association of memories, sensation, and behaviors makes the difference between a great place and some location we just happen to be. Applying the concept of place to the design of enterprise environments enables a design team to get a grip on the complexity of potential spaces and contexts to consider, and allows focusing on creating meaningful places for people to go and stay in when dealing with the enterprise. The basis of this work of place-making is to ground the shaping of environments in the community of actors the space is being made for, and working with local realities.

Enterprise place-making

Research findings and conceptual design decisions are the basis for learning about the places that are potentially relevant. Place-making is an approach with origins in the design of public spaces and urban environments, with a powerful idea at heart — designing great places requires engaging local communities to collaboratively envision and develop their future. Such an approach enables a design team to actively consider what places to create or reshape, instead of solely relying on a client briefing or statistics. Applied to the enterprise, the concept puts the question of how to make places accessible and meaningful for people at the center of the design challenge.

Places are a major part of the fabric of an enterprise, providing the infrastructure for every activity that goes on. In order to make places that make sense for people, they have to be created in a way that implements a larger conceptual vision about the enterprise. To do so, places cannot be designed in isolation, but as a system that considers their meanings, their relationships, connections and shortcuts between them, and the paths people take when traversing them as part of their activities.

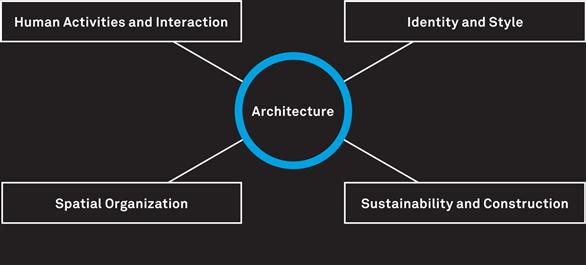

Architecture

The professional field of Architecture is about giving form to the physical environments for human existence. As for many other disciplines, the term architecture in this case refers not to a single practice, but to an entire range of related fields. There are many areas in the wider design and architecture industry concerned with the design of space for people to dwell in. This includes areas such as urban Planning, Landscape Architecture, Building Architecture, and Interior Design, as well as more specific areas such as flight decks or event spaces.

While all of them are concerned with the design of space for humans to dwell in, they are working on different scales of the spectrum and have to work together in order to get the task completed. Architecture is one of the oldest design disciplines, if not the oldest one, since planning and building homes and organizing spaces must have appeared as soon as humankind settled down. As such, the different domains of Architecture enjoy a particularly long tradition and history, with schools of thought, approaches, and philosophies.

As the other design disciplines, Architecture transcends the boundaries between different levels of work on interiors, buildings, and landscapes or urban environments by working with abstract concepts. An architectural project initially works with a topological concept of space, focusing on the relationships and meanings of places to be considered rather than their locations and forms in a geometrical space. The meaning associated to places in turn has to be based on the conceptual aspects of the enterprise they are made for.

As in most design disciplines, the practice of Architecture involves addressing a large variety of considerations:

HUMAN ACTIVITIES AND INTERACTION

designing a space to match and support human behavior. This area involves exploring the purposes and usage scenarios of a space, and their consequences for design decisions. considerations range from large-scale matters like staircase locations to the interior design addressing light, acoustics, signage, color, and furniture.

IDENTITY AND STYLE

embodying values and beliefs in the architecture, going back to the very beginnings of the discipline and visible in government buildings, churches, or other constructions. Today’s company headquarters are often identity landmarks, representing the company or organization using them to customers and the public.

SPATIAL ORGANIZATION

dealing with the definition and separation of areas and rooms through walls, aisles, pillars, and other means of creating zones. This involves defining the relationships between topological locations based on activities and scenarios to support, and mapping these to a geometrical space.

SUSTAINABILITY AND CONSTRUCTION

working with the implementation aspects of Architecture, in terms of economic realities and budget, physical issues of engineering and construction, integration of technology, and meeting regulatory requirements.

Cyberspace is not a place you go to but rather a layer tightly integrated into the world around us.

Institute for the Future

Not long ago, many saw the future of how we use places in Virtual Reality, digital simulations of three-dimensional environments. The possibilities of bringing our physical world into the digital seemed endless, with the prospect of translating largely physical experiences into virtual worlds, such as shopping in a store. Except for specific purposes of games or simulations, we see the opposite is happening— we are not living in a virtual reality, but there is a virtual space expanding into our physical world through touch devices, projections, and other forms of media technologies. Today we find a hidden virtual dimension entering our physical reality, with digital media acting as our loopholes.

For a lot of people working with virtual organizations, the world of work already takes place primarily in that other dimension and only occasionally involves physically going somewhere, with collaboration tools and digital workplace technology for substituting the traditional office space. This does not mean that the physical context of work disappears, but it shifts out of control of the employer and into a private environment. Ensuring a good work environment is just one of the challenges modern enterprises face with regards to their places.

While Architecture as a discipline is clearly focused on the design of physical environments, the principles of place-making can be applied to these virtual spaces as well. Initially much like empty buildings, places occur once people associate them with activities and themes. This applies regardless of the fabric of the space to be designed—essentially because the virtual and the physical are part of the same experience. For the practice of Architecture, Interior Design, and wayfinding, designing places is essentially designing for this blended reality.

Places in the Enterprise

IDENTITY

![]() designing environments to be places where culture manifests itself, think of an office or event space.

designing environments to be places where culture manifests itself, think of an office or event space.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() designing spaces to support the business activities of the enterprise like production facilities.

designing spaces to support the business activities of the enterprise like production facilities.

EXPERIENCE

![]() designing places for experiencing the enterprise and to make people feel comfortable, such as a café.

designing places for experiencing the enterprise and to make people feel comfortable, such as a café.

ACTORS

![]() designing environments to match different actors and support their interactions, such as a trade show.

designing environments to match different actors and support their interactions, such as a trade show.

TOUCHPOINTS

![]() designing environments to act as the physical contexts of human/enterprise interaction — think of online banking.

designing environments to act as the physical contexts of human/enterprise interaction — think of online banking.

SERVICES

![]() designing environments to support carrying out services, for example the Sushi Circle concept.

designing environments to support carrying out services, for example the Sushi Circle concept.

CONTENT

![]() designing environments to support the reception and exchange of content, like the menu display in a restaurant in its interior.

designing environments to support the reception and exchange of content, like the menu display in a restaurant in its interior.

designing environments to support your business model and enable transactions, for example department stores.![]()

PEOPLE

adapting environments to people, such as a university campus with dedicated spaces to study, hear a lecture, or relax.![]()

FUNCTION

designing environments in a way that supports their purpose and functional context, such as calmness in a library.![]()

STRUCTURE

designing environments to reflect a structure, as in production halls organized according to teams or products.![]()

COMMUNICATION

designing narrative environments to enable communication and social interaction, like at a drinks reception.![]()

INFORMATION

designing environments that support wayfinding and information retrieval, for example, in an underground garage.![]()

INTERACTION

designing environments embedding tools and appliances to support user behaviors, such as security checkpoints at the airport.![]()

OPERATIONS

designing environments to facilitate business operations, such as a canteen that supports a smooth flow of guests at lunch time.![]()

ORGANIZATION

designing environments to support team collaboration and organizational structures, like team spaces in an office.![]()

TECHNOLOGY

embedding technology in environments, for example, by placing power outlets.![]()

Rendering The Enterprise Across Channels

The enterprise comes into existence in the tangible elements that it makes available to the people it addresses. We move around in it, changing environments and contexts for certain activities, we deal with objects and artifacts, and we see and interpret various types of messages and symbols. These elements have to be treated as a web of connected elements. People dealing with this reality of hybrid systems transcend the virtual and the physical in overarching journeys. Instead of seeing signs, things, and places as isolated elements, they have to be linked together, a concept also known as cross-channel design.

The blending of channels and the way people use them results in an increased complexity of the design task, accounting for the increasing convergence and tight network of links between them. Design practice is shifting from a world- view of separation to an approach that brings disparate elements together. In general, traditional approaches to the design of signs, things, and places work surprisingly well if applied to the their virtual and blended counterparts, with one peculiarity: they share characteristics of all three concepts at the same time, forcing design practice to adapt and take all these aspects into account. Instead of confining design work on one single medium, this requires us to base the concrete elements on a larger conceptual vision, and to turn this into a rendering.

Enterprise evidencing

The term rendering may seem a bit misplaced when used in the context of an enterprise. This last chapter of the Enterprise Design framework describes the outcomes of a strategic design project, the generation of visible signs, things and places with the intent to have them enter the world. The term is an analogy similar to how it is used in the field of 3D graphics, where a realistic image is created from a carefully crafted model. It involves mastering a set of sophisticated techniques to bring the model to life, considering materials, textures, lights, shadows, and reflections. Rendering the enterprise works in a similar way. The conceptual work delivers a blueprint of the intangible aspects of the enterprise. The tangible outcomes of a design process have to work together as a system to implement the conceptual vision. This comes with a larger degree of complexity, so the conceptual aspects take on a more important role. Initially everything seems equally important, leading to confusion and making it hard to focus. But in our experience it is this task of balancing a proposed solution against the tradeoffs, constraints, and ideas arising from the concept that makes the task of design so interesting. The conceptual aspects have to be behind all design decisions, which is essentially what the Enterprise Design framework is about—connecting design to the reality of life and business that it seeks to reshape.

Example

The field of Game Design is a good example of an emerging subfield, designing outcomes that fall in multiple categories. Games are essentially systems of signs, making a player react to certain messages or symbols on a screen or a physical game board. At the same time, they show characteristics of things — you buy a card game in a box, you can keep it on the shelf in your living room, and it consists of tangible objects. Finally, games can also be seen as places bringing people together — think of virtual multiplayer games, enabling people to spend their time together in a designed environment.

It isn’t a coincidence that it’s much easier to have an opinion on color or font size than it is to make a decision on product positioning.

Luke Wroblewski (lukew.com)

The term cross-channel is mostly used in the context of Media Design, but essentially applies to all kinds of design work. It refers to the practice of considering individual items as part of a larger experience, and designing them as a system that reaches across traditionally separate delivery channels. Every individual part is seen in terms of its role in an overall composite design. This includes physical, virtual, and blended channels, however the characterization depends on the way a device or medium is used.

PHYSICAL

![]() channels are those which are part of the physical environment we live in. Interaction with these channels happens directly through our body.

channels are those which are part of the physical environment we live in. Interaction with these channels happens directly through our body.

VIRTUAL

![]() channels are hidden, and have to be accessed with the help of a device of some sort. They are characterized by the immersion that takes place when we use them, forgetting about the physical world for a while.

channels are hidden, and have to be accessed with the help of a device of some sort. They are characterized by the immersion that takes place when we use them, forgetting about the physical world for a while.

BLENDED

![]() channels share characteristics of both groups, and generally pertain to usage patterns jumping between the physical and the virtual as part of the same activity.

channels share characteristics of both groups, and generally pertain to usage patterns jumping between the physical and the virtual as part of the same activity.

The field of Service Design (which is subject to the services aspect described in Chapter 5) is perhaps the most conceptual and abstract professional field of design that is widely practiced today. In the research of Lynn Shostack, one of the most influential contributors to the field, the visible and tangible components resulting from a design process are referred to as evidences—elements that reveal to the customer an intangible service going on in the background. The pioneering Service Design consultancy live|work used this concept in their work as a means to approach the design of concrete outcomes as potential future evidences of a future service. On their website, they refer to this activity of evidencing as archeology of the future, or digging out what might be.

Applied to strategic design, evidencing is a powerful concept. Although the shift in thinking happens on an abstract level, there is a subtle difference between envisioning an artifact — say, a website — as a design proposal for today, or as tangible evidence of a future implementation of your concept. The idea of shaping signs, things, and places in the enterprise as evidence of a desirable future state is at the heart of the Enterprise Design framework. It aims at the application of conceptual work to produce a visible rendering of the future enterprise. Evidencing helps us translate a conceptual design into an actionable scope of work, to be taken up by the more traditional design practices of creative form-giving.

Embracing design practice

The aspects considered in this chapter make the connection to the sphere of traditional design disciplines, which can be seen as a process of crafting and making artifacts of some sort for a given purpose. It is a professional field combining a long history from different roots and influences with rapidly changing trends. Public opinion sees the discipline mainly through a few star designers in the field of industrial or fashion design, while the profession is slowly recognized as a mainstream discipline that can help in every aspect of life and business. In that endeavor, essential design philosophies such as the teachings of the Bauhaus from 1919 are still applicable and valid in today’s practice.

The large variety of subjects that could be taken on as part of a design process has led to the emergence of so many design fields and specializations that it is sometimes difficult to determine the discipline best suited for a problem, even before struggling to find the right expert designer for the job. On the other hand, the designer’s role is one of integration, of coming up with something concrete grounded in the abstract thinking which is was least initially neutral of a particular medium or field.

The key issue in managing the design process is creating the right relationship between design and all other areas of the corporation.

Donald E. Petersen, Former Ford CEO

Working with the diversity of the field is as much a challenge for its practitioners as it is for their clients commissioning design work. For a p erson with a strong focus on a classic field like Graphic or Product Design, other creative areas often are a blind spot. Mastery of their main medium, through talent, experience, and skills, does not easily translate to another one. There is a need for overlap and collaboration, such as designers and architects working together to put together an exhibition or a signage system, but it is hard for them to break out of their respective boxes. As mentioned before, the emergence of a blended reality of interconnected artifacts that combine the characteristics of signs, things, and places blurs the boundaries. It sparks the need both for generalists and for experts in certain creative subfields.

For strategic design initiatives in the enterprise context, there is a need to bring together generalists and specialists, talent and collaborators, as well as rational conceptual thinking and opportunistic external inspiration. Design professionals rely on the ability to walk through the world with open eyes, an open mind, and the possibility to transfer things from here to there. The best ideas and approaches in design often come unexpectedly and from somewhere outside the thinking about the design challenge itself, or from dialogues between experts in seemingly unrelated fields. The tension between these different approaches makes the case for actively managing the way design is practiced in an organization, and adapting it to the specific situation and challenges of the enterprise.

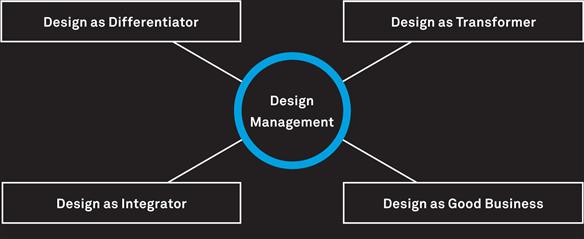

Design Management

The professional area of Design Management is about making design work as a competency for an organization. It is concerned with putting into place the formal structures that such leverage requires, but also sparking and sustaining a culture of creative experimentation in all aspects of the business. on a more concrete level, Design Managers need to establish systems of governance and asset management, manage internal design resources and external partners commissioned with design work, and facilitate the integration of this work into the functions and business areas of the organization.

Although many organizations realize the potential and the need to employ design as part of their capability set to achieve innovation and market differentiation, the aspect of formally managing design is often neglected or overlooked — instead, the practice is vaguely seen in the area of creativity, often assumed to be rather unmanageable both in terms of processes and people. This is reflected in the teachings of some business schools, putting out dogmas like "never hire a designer" for the reason of not to stifle their creativity by a nine to five job.

To advance to the next level of integration beyond a superficial and therefore ineffective use of design, it has to be managed systematically as a strategic competency much as any other. This involves orchestrating a complex piece of teamwork, aligned with a long-term vision where to go. It requires putting into place design programs, strategy, governance processes and change Management to embed it into the regular business practice of the organization. In the next part of Intersection, we will share our experience on how to make a strategic design initiative happen as a program and capability.

The Four Powers of Design: A Value Model in Design Management, Design Management Review, Vol. 17(2) 2006, Pages 44–53

French scientist Brigitte Borja de Mozota developed a scientific model on the role of design in organizations. The Four Powers of Design differentiate levels of integration:

DESIGN AS DIFFERENTIATOR

Establishing a design competency for Marketing purposes, as a means to differentiate products and influence customer behavior. It uses Communication Design to position brands in advertising, product packaging and visual brand identity, while the products and services themselves are untouched.

DESIGN AS INTEGRATOR

The design competency is used for its creative input for the enterprise, as a management tool for innovation. The integration happens on the level of idea generation and exploitation, and focusing on human-centric approaches. It employs product-oriented disciplines such as Industrial and Interaction Design.

DESIGN AS TRANSFORMER

The design competency is seen as a strategic enabler for all sorts of problems, supported by senior management and firmly grounded in the organizational culture. It focuses on creating business opportunities, and is therefore linked with Business Design and Architecture and Organizational Design.

DESIGN AS GOOD BUSINESS

The third level of design integration into an organization is both broad and deep, touching virtually every area and function. Design is part of the DNA of the company and therefore an intrinsic part of every endeavor.

To deliver on its promise to draw a picture of the future, any strategic design initiative needs to result in visible and tangible outcomes as evidence of an evolved enterprise. This requires working with talented designers of relevant fields, embodying abstract concepts, and generating ideas for a hybrid system that spans the virtual and the physical reality of the enterprise.

Recommendations

Design systems of signs that effectively encode the overall story of the enterprise and its key messages into media, and apply them consistently

Produce things according to their roles both as useful tools and artifacts of the enterprise as a cultural space, adapting them to their use context and causing behavioral change

Provide personal, meaningful places as environments to support the activities of the enterprise, and enable people to find their ways and inhabit places important to them

Use the Rendering aspects to map and create paths and links between all these designed elements as part of an overarching Design Management, accounting for their role as triggers for the intended change to happen

Case Study _ Bbva

BBVA’S ENTERPRISE

Simplifying banking and delighting customers, to become the people’s favorite bank - working towards a better future for people.

As one of the biggest financial groups in the world, Spanish Grupo BBVA today serves over 50 million clients in 32 countries, with various offerings in banking, insurance, and related services, and looks back on over 150 years of history. A strong market segment of the company is the retail business, where the bank is present in many markets with a network of branch offices and a wide range of services for personal and small business banking.

Driven by a management paradigm that focuses on value creation for people, the group has launched the BBVA Innovation Center. Its initiatives reach across all business units, functional departments, and services. Although the banking sector is one of the oldest in the world, management believed that there is still a lot of innovation possible in the area of dealing with people. tte company strives to make people’s lives easier by offering transparent and simple solutions, integrated into daily activities. This innovation initiative is approached like an industrial process, creating value for people in a sustainable way.

As part of these activities, BBVA launched a strategic design program with a strong focus on cross-area innovation. In a series of projects, BBVA addressed a variety of design themes, using a design-driven approach to produce remarkable outcomes as part of the Rendering of their enterprise. tte group has worked with some of the most renowned design consultancies such as IDEO, Saffron, Continuum, and Fjord. All design work is embedded in a network of academic partners and technology vendors. Achieving such outcomes would be impossible without the underlying conceptual decisions, bringing together enthusiasm, strategic vision, and attention to detail. Although BBVA’s design program is about producing tangible results, it is their role for people in touch with the enterprise that makes them meaningful.

The future of innovation can only have one purpose: to make people’s lives easier. It is useful, practical, focused on actual solutions, meaningful, user-centered, functional and ergonomic. It must add value, to close gaps.

Ignacio Villoch

Signs

![]() As in all large companies, BBVA group is in constant exchange with a large and diverse enterprise environment. As part of the innovation initiative, the company looked for new ways to engage its entire range of stakeholders and drive the communication process. As a result of the design process, the company overhauled the media elements of its brand identity, and applied it across all its messages, communication platforms and other sign-based systems facilitating this exchange. Elements such as a defined visual language and tone of voice are the basis for a coherent presentation across all these Rendering elements.

As in all large companies, BBVA group is in constant exchange with a large and diverse enterprise environment. As part of the innovation initiative, the company looked for new ways to engage its entire range of stakeholders and drive the communication process. As a result of the design process, the company overhauled the media elements of its brand identity, and applied it across all its messages, communication platforms and other sign-based systems facilitating this exchange. Elements such as a defined visual language and tone of voice are the basis for a coherent presentation across all these Rendering elements.

Based on the paradigm of open communication, BBVA moved away from the traditional ways of corporate communications such as publishing polished reports. Instead, it concentrates on formats such as online media, videos, and micro-blogging, developing new channels to distribute its messages and facilitate a two-way conversation. Driven by the goal of a better future, the group addresses topics of sustainable and inclusive banking, openly co-creating new solutions with their environment. These formats enable BBVA to tell the story of their enterprise beyond the one-way messaging of the past. This ranges from visualizations based on the group’s huge base of transactional data, to sponsoring Spain’s national soccer league, connecting to people by placing signs in their reality.

The same fundamental sign systems are used to shape the Customer Experience of BBVA. The conceptual design decisions behind BBVA’s offerings are based on radical simplification, equally represented in the visual clarity of signs used for Marketing materials or tangible elements of a product offering like different credit card options, designed to communicate the difference instantaneously and unambiguously. Another task of sign systems is structuring BBVA’s digital systems across different services and devices, offering a system of simple, elegant, and reduced tools to the client—but also to internal systems for employees, reporting for investors, and communications to the public. The conceptual design choices about the way people interact and communicate are the basis for a systematic use and distribution of signs within BBVA’s enterprise environment.

Things

BBVA’s innovation initiative turns the design themes identified into vision projects, always with the goal of translating ideas into concrete outcomes. In such open-ended settings, BBVA is indifferent whether such an outcome would reside in Marketing, internal operations, products and services, or other functions, or span multiple areas. Any activity by a stakeholder group that could be supported is a potential case for a tool, a physical or virtual artifact created to address a concrete need.![]()

One of the most famous projects of the BBVA Innovation Center is ABIL, its next- generation vision of the ATM — a field where not much has changed for decades. Initially looking at ways to bring more offerings into the self-service channel, BBVA quickly discovered that many of the current functions of their kiosk systems were not used. Apart from cash withdrawal, most customers preferred waiting in queues for a human operator, even though the functionality was available in the self-service environment. So instead of adding new functions, the design team realized it had to make the existing ones much more accessible, simpler, and better adapted to the customer.

In a four-year project, the BBVA Innovation Center adopted a design-led approach together with the American consultancy IDEO, starting with extensive research and conceptual design to bring together human activities and the corresponding interactions and transactions. Based on a collaboration of over 30 professionals from many different fields of design and related areas as well as finance and technology professionals, the design team conceived, prototyped, tested and iteratively defined the ATM of the future, which is currently being rolled out in branches. It addresses issues of privacy, security, transparency, and efficiency with an elegant and dynamic interface design, making interactions much more fluid and humane than any of its predecessors.

In similar projects, BBVA redesigned its online services, produced apps for mobile banking and investment, and physical evidences such as credit cards — all considered as part of a larger customer journey. Moreover, BBVA produces tools for internal or external use with the same approaches. BBVA makes heavy use of custom iPad apps for staff activities, aiming to make their workforce more productive in any situation, including interactions with customers.

Places

As a company active in the retail banking sector, BBVA is at the forefront of the shift from physical to virtual environments where their business is happening, resulting in a set of highly disruptive developments. Many customers interact exclusively via online banking, mobile apps, and other distance services. Employees are empowered to work from home, working with a cloud-based intranet and remote tools. Even face-to-face meetings in the branches are facilitated using these tools, bringing in experts from other locations as needed using video calls. Finally, conversations move to entirely different virtual places, including social media such as YouTube, Twitter, or Facebook, both with customers and other stakeholders.![]()

BBVA has recognized that this new reality has to be addressed by making places that fit their context of use, bringing together elements of physical, virtual, and hybrid spaces. These places are the basis for interaction and conversation that drive business processes, customer interactions, stakeholder communication, and other essential activities of the enterprise. Led by the BBVA Innovation Center and based on a large conceptual body of work, the group introduced places on the web dedicated to various themes, target groups, and activities. They all are part of one larger, overarching concept, providing paths from one to another and guiding people on their individual journeys.

The blog platform Bancaparatodos (a bank for all) is an example of an owned place dedicated to an open exchange with the whole stakeholder community— including everyone interested in participating. Focusing on social topics such as financial inclusion and service availability to everyone, responsible investing, and financial literacy, it is a place to discuss and share ideas. It gives the innovation center a place to co-create the future of banking with others.

In any case, the design of the spaces strives to make places that relate to the purpose and activities to be addressed. Physical facilities such as branch offices and interiors, and virtual or hybrid places, are made to drive interactions and conversations. They combine connections on a social level with working touch- points for the actual interactions — for example, the bank’s Twitter team is ready to discuss the future of banking with you, or help you with a problem in your online service. With their place-making strategy, BBVA attempts to be where people are — a strategy also reflected in sponsoring Spain’s LigaBBVA.