4

Big Picture

The Enterprise Design approach is based on the idea that in the individual perception of people, any visible manifestation of an enterprise is just a single element along a greater journey of interactions. This applies to everything people can see or use in the enterprise space, like websites, documents, communication channels, or retail stores. Any person in contact with an enterprise experiences a different subset of those elements, depending on the relationship to the enterprise and the activities being carried out.

The relationship between an enterprise and human beings vary in nature, and reflect various roles: people act as customers, partners, employees, or job candidates, sometimes on their own account, and sometimes representing a group or organization.

Instead of addressing each of these business cases, target groups, and communication channels one by one and producing more and more disconnected tools that add to the complexity, the Enterprise Design approach aims to respond to everything a person wants or needs in a coherent and integrated fashion.

By making those pieces work together in an overarching design, an organization can give itself a consistent shape across everything people experience when interacting with it, in a way that ensures no relevant aspect of that interaction happens without explicit intent. This provides a way to address a person’s needs along the entire experience, and to purposefully connect people to each other. Anything an organization owns or influences in the enterprise should be integrated into that design.

Example

Your relationship to a public transport service is determined by being a customer and a passenger. Every engagement with them—going somewhere from A to B—involves a series of steps: looking for a suitable connection, booking a ticket, travelling to the station, boarding the train, finding your seat, showing your ticket, arriving at your destination. Depending on your satisfaction with their services, your experience might also involve dealing with customer service to request compensation for a delay or other problems encountered, or participating in a reward program.

Examples for other relationships to that company include that of an investor holding shares, the clerk at the ticket counter or a train conductor—people fulfilling those roles are stakeholders of the enterprise, and contribute to what people within its realm experience.

This may seem like a huge, overwhelmingly complex task, and in some ways it is. To be able to craft a design for something as abstract and loosely bound as an enterprise, we need to take a step back to look at it again from some distance. By examining the way the enterprise is perceived by people being addressed, and decomposing the elements that constitute it in this perception, we can develop a better understanding of the problem as a whole.

This chapter describes three universal high-level aspects of any enterprise, as an approach to develop a holistic understanding about it as a complex system. It portrays today’s established practices, addressing design concerns related to each of them.

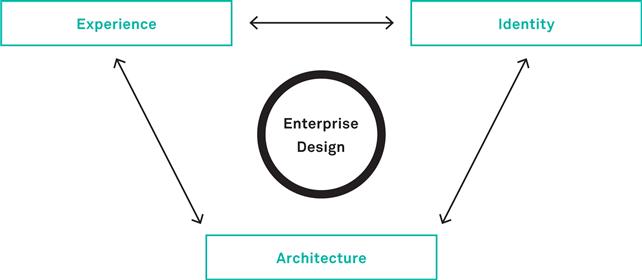

Identity, architecture, and experience

Any enterprise of substantial size is by nature a complex entity. It carries out a huge number of transactions and operations every day, involving the assembly of work products, decision making and communication, in exchanges with customers, suppliers, partners, investors, and other stakeholders. It launches projects and programs, and develops elaborate structures to manage the various assets and relationships it needs to operate and evolve. These challenges apply to commercial businesses as well as to non-profit organizations, public bodies, and other forms of enterprises.

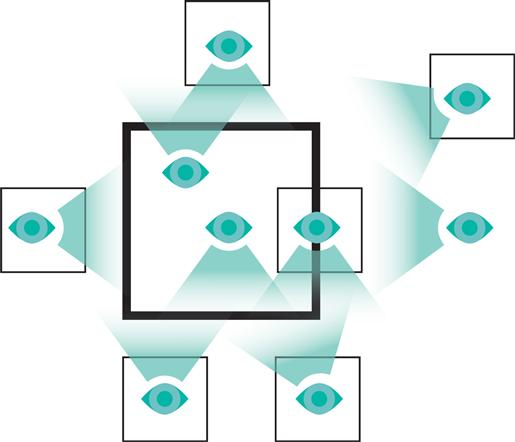

Consequently, addressing the concerns of an enterprise in its entirety requires looking beyond a single organization or market player at the larger ecosystem it is embedded in. Each actor of an enterprise has a different view on it, usually putting itself at the center and related parties at its periphery. All relevant parties like customers, external partners, and stakeholders have to be part of any comprehensive view on the enterprise, looking at that core organization together with every stakeholder it relates to.

Most approaches to thinking about an enterprise in a holistic way involve a certain degree of abstraction and the use of metaphors. This is needed to circumvent the inherent complexity in analyzing or modeling such dynamic and mingled structures. Such models picture the enterprise as a building or a city to be planned and constructed, as a personality with certain characteristics, as a living organism, or as a machine carrying out a given process.

To create a conceptual foundation for the Enterprise Design framework—to determine what actually is to be designed—we use the same type of abstraction to describe in Big Picture terms what constitutes an enterprise in the eyes of people. Using such simplified concepts as a paradigm to form a model of the enterprise helps to understand it as the subject of the design approach, and the context in which that design will be applied.

These aspects describe universal qualities that apply to any enterprise of all kinds and sizes, regardless of whether its management bodies are aware of them and if they have been consciously addressed. They provide a way to understand how an enterprise establishes human relationships, how it is perceived, experienced, and implemented by the people involved in its activities. Any design initiative carried out in an enterprise context aims to interpret and then proactively re-shape these qualities. On the following pages, each aspect is explored in more detail.

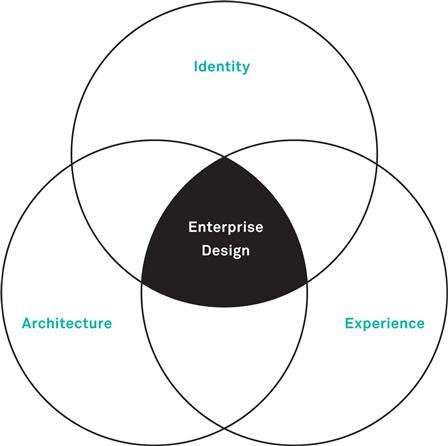

There are three universal qualities of all enterprises used as the Big picture aspects of the Enterprise Design framework:

IDENTITY

what people think and feel about it — the enterprise as a mesh of personalities, impressions, and images in people’s minds, expressed in symbols, language, and culture and reflecting a shared sense of purpose.![]()

ARCHITECTURE

how it works and functions — the enterprise as a purposefully designed system of control structures, resources, assets, processes, and tools being put in place to make it work.![]()

EXPERIENCE

what people get out of it — the enterprise as a space for interactions of people, environments, and artifacts, and how it addresses human motivation, perception, and behavior.![]()

#1 Identity

Whenever people engage in a conversation with others, they somehow present themselves as individuals with a distinct identity, having attitudes and values, conveying beliefs and assumptions. Likewise, when an organization interacts with the people and groups it is related to, it expresses an identity—in the way it looks and communicates, and in the way it behaves as an entity. Its effects range from the short relationship between a small shop and a one-time customer to the relationship of large corporations to entire societies. In the eyes and minds of people, that identity constitutes a certain image, which is the way identity is perceived by others.

In terms of identity, the enterprise is a space of actors in constant exchange. Organizations, individual people, teams or departments, services and functions — all of these actors have distinct identities and images of each other. In all interactions and conversations that happen inside the enterprise space, identities are communicated and used as differentiators and means of positioning. Just as people dress in a particular way, use language styles, or present themselves in social media to express their identities, organizations make use of visible attributes and messaging to constitute their identity. The identities expressed in an enterprise context reflect the relationships between the actors involved, their roles and responsibilities.

Expressing identity

Over time, every actor in the enterprise develops a set of images in his or her mind, shaped by the impressions that identities made at each point of contact, or touchpoint. In reality, this is the only place where identities in the enterprise come to life: in people’s minds. For an impersonal consumer product, this means the image the target audience projects onto its brand, and its expression of an identity that fits. In the case of a shared organizational identity, it is more about creating a shared understanding between its management, staff, other stakeholders and the public of what it is about and stands for. It is influenced by multiple factors such as the organization’s past, things influential people say or do, and its accomplishments and failures.

Example

The image of major oil companies has fairly suffered in the past decades due to some particularly ignorant behavior, scrutinized by the public—think of the Brent Spar oil platform disposal or the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. In both cases, the identity expressed by the organizations appeared to be largely ignorant of the negative effects of their work on the environment, resulting in a bad image and a seriously damaged relationship to a significant part of the population, leading the companies into serious economic trouble. While these companies might have been conscious of the they identity expressed towards their shareholders, they failed to behave in a way that would ensure a good relationship with the public.

The 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico

To understand the concept of an enterprise as a space of identities, we have to look at the way these identities manifest themselves in an enterprise’s daily business and life. Based on a rather passive idea, identity takes on an active role as the culture emerging in and around an organization, lived in everyday practice. It manifests itself implicitly in the habits, assumptions, beliefs, and attitudes which are shared by its staff and which underpin the organization’s activities. Culture becomes visible to people inside and outside its boundaries in emerging explicit expressions, as symbols, messages, conversations, and behaviors. Examples of visible elements are the way meetings are being facilitated, the design of office interiors, or writing styles applied to email messages.

Neither organizations, nor groups nor individuals are necessarily conscious about their identity. To be effective, management has to align its strategy and vision of an organization’s future with the identity shared by the people important to its success. This includes the culture that people within its boundaries are creating, as well as the images that external stakeholders have of it.

Shaping Identity

Identities are first and foremost abstract concepts inside of people’s minds. As such, they do not only express themselves visibly, but they are constituted by perceivable elements. Messages, symbols and their meanings, behavior of role models and leaders—all those visible elements act as triggers for an emerging identity. They cause changes in individual and shared ideas, and broadly influence the resulting culture.

Any person having an idea of itself and the groups it belongs to has an identity, as have those groups themselves whose members share a common perception of their identity. it is the vision of who you are, who you want to be, and how you want to be seen by others. such ideas exist for people, for companies and other types of groups, but also for services or products in the minds of their creators and consumers. in the enterprise context, different types of identities are relevant:

SHARED IDENTITIES

are those expressed by organizations and groups such as customers, suppliers and partners, but also by departments, countries or other types of groupings inside an organization. in small and young companies, these are largely influenced by the personal identity of influential leaders like a company founder. Shared identity is often subject to branding initiatives, aiming to actively shape the way that identity is expressed to the market and internal or external stakeholders.

are those expressed by organizations and groups such as customers, suppliers and partners, but also by departments, countries or other types of groupings inside an organization. in small and young companies, these are largely influenced by the personal identity of influential leaders like a company founder. Shared identity is often subject to branding initiatives, aiming to actively shape the way that identity is expressed to the market and internal or external stakeholders.

PERSONAL IDENTITIES

of people are the conception and expression of individuality and group affiliations, influences by social, economic, ethnic, or religious backgrounds. in the enterprise, personal identities are intertwined with shared identities since people often act on behalf of organizations, and affiliation with a shared identity in turn becomes part of their personal identity — like being a Mac user or member of a club. The other way around, people express different identities or personas according to contexts, such as private or business communications.

of people are the conception and expression of individuality and group affiliations, influences by social, economic, ethnic, or religious backgrounds. in the enterprise, personal identities are intertwined with shared identities since people often act on behalf of organizations, and affiliation with a shared identity in turn becomes part of their personal identity — like being a Mac user or member of a club. The other way around, people express different identities or personas according to contexts, such as private or business communications.

IMPERSONAL IDENTITIES

are those attributed to an abstract concept or artifact, such as trademarks for products or services. These identities are often created to position an offering in the market or to communicate a certain quality of a product, attempting to give it a personality that is reflected in its brand identity. in some cases, impersonal identities can overlap with the shared identities of groups, such as a team working on a certain product.

are those attributed to an abstract concept or artifact, such as trademarks for products or services. These identities are often created to position an offering in the market or to communicate a certain quality of a product, attempting to give it a personality that is reflected in its brand identity. in some cases, impersonal identities can overlap with the shared identities of groups, such as a team working on a certain product.

Branding

A brand is simply an organization, or a product, or service with a personality. So why all the fuss?

Wally Olins, Chairman, Saffron Brand Consultants

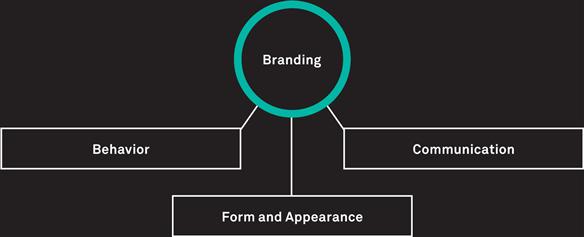

Branding is the practice of actively shaping the way an identity is perceived by audiences important to the person or group it belongs to. While the concept of Branding can be applied to all kinds of shared, impersonal and also personal identities (Personal Branding), the predominant form of use in the enterprise is on the organizational level. This activity is usually referred to as Corporate Branding.

A successful brand project has to be deeply grounded in the strategic vision of its leadership while being aware of the culture and images in the organization. It strives to turn that vision into a comprehensive formulation that communicates it and makes it clear, audible, and visible as a coherent message. It reaches out to everyone important to the organization to shape their perception and image of it, and also seeks to shape the behavior and culture of all people involved in making it run — predominantly employees, but also external partners or even customers.

Branding initiatives have the goal to strengthen consistency, build reputation, and generate meaning for all stakeholders concerned. They typically result in a new or evolved visual design appliedto visible artifacts produced by the organization, such as messages, products, and events. To be have an impact beyond the visible, they also address new guidelines for communication or personal conduct, such as the tone of voice used in messages.

To have profound impact on the daily business—for example to change the way customers are treated by staff or the quality of customer service—brand initiatives have to engage in extensive change management and influence everything and everyone involved in its activities.

In particular, Branding initiatives usually attempt to give a shape to three different manifestations of identity:

FORM AND APPEARANCE

everything an organization produces that is visible to its various stakeholders, including products and services, physical and virtual environments, documents,and other kinds of artifacts.

COMMUNICATION

everything an organization says in public or in private to people inside or outside its boundaries, including press releases, advertising, and communication with individuals.

BEHAVIOR

everything an organization does when dealing with individuals or groups of any kind, including service execution, behavior of representatives, and operations visible to the public.

The central problem of brand building is to get a complex organization to execute a simple idea.

Marty Neumeier, author of Zag and The Brand Gap

Today, Branding is entering a period where it engages not just customers and employees, but all members of the enterprise of which it is part.

Mary Jo Hatch & Majken schultz in Taking Brand Initiative

When leaders of an established organization perceive a gap between their vision and the reality of its identity as lived in daily business, they seek ways to recreate or clarify the idea shared by everyone of what the organization is about—whether consciously making this part of a corporate identity program or informally pursuing similar goals. Startup businesses face a similar challenge when they invent a new identity from scratch to establish a new enterprise as an ecosystem to do business with. This is the goal of branding initiatives, to make the vision visible for employees, customers, and other stakeholders in the enterprise.

Identities in the enterprise

Identity is a ubiquitous quality of every activity in the enterprise. It is expressed as behaviors, messages, and symbols. It drives the creation and delivery of products and services, the content and style of communication activities, the design of physical and digital environments, and the behavior towards internal and external stakeholders. It touches every part of an enterprise, every audience, always and everywhere.

In its quest to define and shape identity, Branding as a professional discipline has overcome its fixation on the relationship to consumers and products, and evolved from being a pure Marketing function to a common effort that involves all parts of the organization. All activities, regardless of whether they are traditionally part of Marketing, HR, Communication, Finance, or IT, are building on the corporate brand as a channel to reach out to people, and as a way to establish a shared identity.

We believe rebrands should create symbols of change, not just a change of symbol.

Simon Manchipp (someoneinlondon.com)

Brands equals interface not surface.

Oliver Reichenstein (informationarchitects.jp)

To deal with the complexity and dynamics of the enterprise with its wide diversity of stakeholder relationships, Branding initiatives themselves need to become much more flexible and dynamic than before. As a static collection of visuals and guidelines, communication and messaging, or a series of internal events, they fall short of their promise of transforming the way the enterprise actually works and reaching and engaging all relevant stakeholders.

A platform for social exchange

Instead of a one-way communication activity, branding initiatives addressing the enterprise with all its activities have to establish identities in ongoing conversations. They have to become symbols exchanged in a constantly changing, highly dynamic environment of social relationships. Reaching beyond traditional control zones such as product packaging, the corporate intranet, or office interiors, they must be present in all conversations going on in the enterprise, among a variety of stakeholders, and across all communication channels.

From a people perspective, this means that brands are perceived more as an identity, as a person rather than as a style or property. Just as with a person you meet on the street, people have to be convinced and persuaded to engage in a relationship with a brand, and have a clear idea of what it can do for them. Therefore, brands must provide a context for interaction to encourage social exchange and participation, acting as welcoming hosts for the people they address.

A brand that acts as such a platform is embedding the question of who we are in daily operations and behavior, and encouraging information exchange among all stakeholders in shared spaces. It is visible in traditional media, physical environments, communication channels, and digital media such as Facebook or virtual workspaces shared with business partners. It seeks to influence rather than control, and flexibly supports Co-Branding with other identities, sometimes as host and sometimes as guest. It is fluid, adaptive to context, tangible, and approachable. In all these situations, it is consistent and clear in what it says and does, and reliably delivers on its promises.

In order to become a ubiquitous platform for everything an enterprise is doing, identities have to be implemented in concrete designs. The qualities to be expressed must be encoded in the messages, behaviors, and appearances experienced by people.

The identity aspect helps to understand how the intended result of a design process interprets, expresses and influences identity, and thereby shapes the way actors in the enterprise are perceived by others. By looking at the way an identity is seen by a stakeholder, a design can purposefully interpret and transform it into something visible and usable, to express its qualities in the distinctive signatures driving their experiences. Programs to shape identities are not easily implemented—after their definition and introduction, they have to be lived in everyday business, and constantly adapted to new conditions. This is where the Architecture aspect comes into play, the formal structures underpinning the enterprise and all its activities.

#2 Architecture

Any enterprise, regardless of type and size, is based on a complex set of fundamental structures facilitating its daily operations. The term architecture, when applied to an enterprise, refers to all the formal structures put in place to make it work. It represents the way an enterprise is constructed and functions as a consciously designed, man-made socio-technical system. Architectural structures underpin all activities going on between the actors involved in its endeavors.

Working with the architecture quality of the enterprise involves anything that enables organizing work and facilitating communication, automating business processes with the help of technical systems, establishing rules and policies, managing assets, resources, and events, as well as running the programs and projects to transform the way these elements work together.

Many of the people involved and impacted by these structures and dealing with the enterprise in some sort of stakeholder relationship, the architecture implementing the enterprise is largely beyond view. The results of its work, however, are quite visible: architecture determines how well an organization can assure service quality, how quickly decisions ripple through its reporting lines, or in what way it reacts to one out of hundreds of customer requests. Every time people interact with or within an enterprise, its architecture largely affects what they get back from it.

Exploring architecture

The architecture aspect captures how the enterprise does what it has been created for. This includes a large number and variety of connected structures and substructures. Just as there is not only one identity in the enterprise, there is no single architecture, but a complex system of intertwined and overlapping structures, some of them describing the same elements but focusing on different aspects, and using varying terms.

Depending on the chosen perspective, an architectural description might encompass the structures of a single organization, or the entire supply and sales operation system including structures shared with customers and suppliers. It might describe how to produce and deliver products and services, communication channels, and management systems, or how the enterprise relates to investors and raises investments.

Example

Think about the last time you used a logistics or postal service. Did they pick up and deliver your package on time without delays or errors? Did it arrive in the shape that you expected, or was it broken on the way? Were you able to track the delivery process on the web? All those aspects of their service depend on the formal structures that make the enterprise work, including vehicle and route management, data exchange, manual and automated workflows. To be successful, the architecture behind the service has to be designed for speed of execution, quality assurance, exception handling, and steady communication across the delivery process.

Working with architecture

Running an enterprise inevitably involves putting these structures in place, either consciously or just as they emerge in daily business. Processes, roles and responsibilities, information exchange, and some kind of office space are elements you will find in any organization. Their importance in individual cases depends on various factors such as the individual industry, the number of actors involved, or the size of the organization.

Enterprise relationships captured in architectural descriptions form a complex and intertwined structure of structures, undergoing constant change. Individual substructures cannot be viewed and addressed as static constructs in isolation, since they are difficult to separate and largely depend on each other to work—changing one means affecting others as well. Many formal structures in the enterprise, like social and organizational configurations, tend to change very quickly. Any attempt to capture a holistic enterprise-wide architecture can only capture a moment in this development or lay out the direction of this transformation, by modeling a current or a desired state.

For those reasons, any work on architecture deals primarily with the complexity and ambiguity that comes with the large elaborate structures in constant transition that you typically find in an enterprise. While it is impossible to control such a system as a whole, initiatives aiming to shap e architecture have to influence it by establishing controlled substructures, understanding the linkages between them, and managing change and development.

As the set of structures driving all execution, architecture is intrinsically subject to all transformation processes in an enterprise. To be aligned with strategic intent and vision, it needs to be understood as it emerges dynamically, and consciously transformed to fulfill the purpose of the enterprise. This is true even if the goal of this transformation is to maintain the status quo of the enterprise by adapting to changed conditions.

To understand these structures and inform management, decision making and governance, architecture models are used to describe or visualize all structures in the enterprise. They show stakeholders both a view on the current situation and alternative developments to be considered. The instrument of choice for this is Enterprise Architecture, a discipline that aims to make architecture visible to stakeholders involved in or impacted by a transformation.

Example

IT Network architecture to enable data exchange between computers or other devices is quite important for most businesses to operate, but it is certainly more important for certain industries. For an internet service provider it is at the heart of the business, while it might be tolerable for a farm to be cut off from the internet for a few hours. For other industries, it might be physical facilities, financial resources, or other structures that turn out to be particularly relevant. The amount of effort and investment spent in designing, implementing, and optimizing a specific aspect of architecture therefore varies from case to case, and is dependent on the business model that applies.

CERN Computer Center

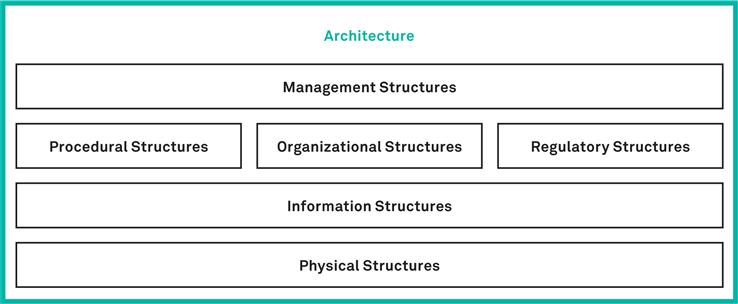

To develop an understanding of the structures relevant for a design problem, architecture has to be discovered and described, and focus on particular types of structures depending on what is relevant for that purpose:

Management Structures

and governance systems to steer operations, performance, and development of organizations and lead the enterprise to desired results, described as performance measurement and reporting structures and used in scorecards or evaluations.

PROCEDURAL STRUCTURES

to execute operations, create products and services, collaborate with external partners, implement business functions, and take care of exceptions and emergencies, described as linked steps of business processes and used to manage activities.

REGULATORY STRUCTURES

establishing guidelines, policies, and rules described as decision statements and control structures as a basis to guide business decisions, and used to direct human and automated decision making and control financial transactions.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES

dividing organizations into business units to manage work and choices being made, measure success, and handle processes with human involvement, described as formal relationships between people and groups, and used to define and manage roles and responsibilities.

INFORMATION STRUCTURES

implemented in systems and communication channels to handle and exchange data, implement asset inventories, messaging systems or knowledge repositories, described as technical components on different layers and used to manage information availability.

PHYSICAL STRUCTURES

used for operations such as buildings and facilities, machines, and energy supply and transportation systems, described as assets used to enable business operations.

Enterprise Architecture

That set of descriptive representations (models) that are relevant for describing an Enterprise such that it can be produced to management’s requirements (quality) and maintained over the period of its useful life (change).

John A. Zachman (zachman.com)

Architecting as a discipline is probably among the most ancient activities of humankind. It has emerged to deal with the complexity of structural decisions involved in creating stable and durable buildings serving a wide range of purposes. Today, business leaders find themselves in a similar situation when planning and crafting their businesses, making decisions steering their development. Enterprise Architecture is an instrument to implement a strategy by exploring and reshaping structures in the enterprise. It translates business vision into execution by understanding how an enterprise works, modeling its potential future, and informing management and governance to drive decision making. The outcomes of Enterprise Architecture initiatives are maps of all kinds of systems in the enterprise and their relationships, along with goal-directed analysis, optimization, and restructuring to make the enterprise more efficient, robust, and integrated.

The use of multiple viewpoints enables those initiatives to address specific stakeholders individually and to deliver insights relating to their particular concerns. Such a view concentrates on a specific subset of details while leaving others out of the picture. Examples of such a view include models of the business processes, models on technology usage, or models illustrating information flows and critical paths. Viewpoints of Enterprise Architecture have the goal of capturing just the right amount of information to inform stakeholders without providing too much detail.

As an endeavor potentially touching every aspect of daily business, Enterprise Architecture initiatives must have the connections, authority, and alignment needed to bridge between organizational silos, and to trigger transformation processes just about everywhere in the enterprise. Business strategy and policies must form the foundation of the architectural principles used to inform the creation of those structures. Such initiatives face not only the complexity challenge of developing holistic and accurate models, but also of turning a redesigned model into projects, products, and processes that will have a real impact on the actual structures that drive the enterprise.

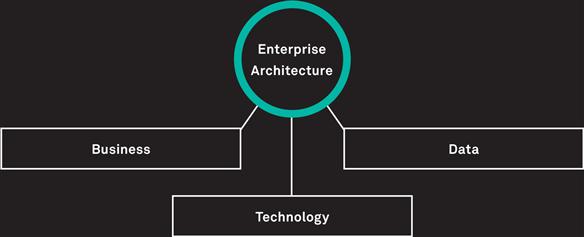

Today’s frameworks typically concentrate on three major topics:

BUSINESS

illustrating the business model as system of financial streams, business capabilities, process and events, organizational structures and policies.

DATA

illustrating the use and flow of information in the enterprise, including consolidated data models on entities and their relationships, metadata and quality management, reporting and analytics.

TECHNOLOGY

illustrating the technical structures the enterprise uses to operate, such as applications, network infrastructure, computing resources, machines and appliances, or technical standards.

It’s always about people. No matter how technical a problem may seem, ultimately it’s always a people- problem.

Tom Graves, Enterprise Architect and Principal, Tetradian Consulting

The human side of architecture

Historically, the discipline of Enterprise Architecture concentrated on shaping complex IT and technology architectures in alignment with business requirements. Today’s practitioners expand their scope to address all structures that constitute an enterprise and make it work. Organizational reporting lines, information systems delivering data, processes driven by automated systems and human decisions—all these structures are just different aspects of the same system. The resulting architecture is the foundation of every single step the enterprise takes, from sending a receipt to a customer to a merger with another organization. Just as buildings are structures made for people to live in and look at, enterprises are structures made by people for people as a space for interactions and transactions. In consequence, people themselves cannot be seen as assets to be incorporated in an architectural description, only the enterprise’s relationship to them. Any person in touch with an enterprise is both a user of its architecture and a contributor to it.

Designing visible architectures

The structures described in an Enterprise Architecture model ultimately enable the enterprise to reach out to people, facilitating all transactions and interactions with them. The systems constituting the architectural elements of an enterprise are driving these exchanges. They are visible to people as tools and services to solve tasks and make decisions, as information assets, communication channels, and workflows. They take concrete form in physical and virtual spaces, in personal conversations, phone calls, or web-based transactions, enabling people to interact with the enterprise.

Instead of being approached as a pure background process, Enterprise Architecture initiatives need to be aware of this role and design architectures that deliver real value to people in accessible systems. They should implement the strategic vision in a systematic fashion to address customers, employees, and other stakeholders by designing systems suited to their particular needs. They should result in concrete designs visible to and usable by people.

Applying the architecture aspect helps to explain how a design depends on the structure of the enterprise, and how it implements architectural decisions and principles to form a part of the same structure. Architecture as universal quality of the enterprise is an inherent part of every design that largely influences how it works and what people get out of it in individual experiences.

#3 Experience

The identity and architecture aspects described earlier are both attempts to understand and describe the enterprise as an entity, the way it works and the way it expresses its personality. In the real world, the enterprise as a whole remains an abstract concept, largely invisible to people. The only things people in touch with or related to an enterprise actually get to see are a subset of its concrete manifestations.

The term experience refers to the individual interactions with these manifestations. Every time a person is exposed to the products and services, buildings and spaces, messages and dialogues, or websites and information systems of an enterprise, those offerings become an element within that person’s experience. The experience aspect of the enterprise defines it as a space wherein people are experiencing its concrete appearances, represented by other people, technology, or artifacts, everywhere and all the time. In that space, every stakeholder, every customer, employee, investor, or other person with a relationship to the enterprise is experiencing it in some way through these appearances. This viewpoint is not about how the enterprise works on the inside or what values and qualities it is associated with, because in their daily lives, people rightfully don’t care much about these things. The experience aspect allows us to look at the enterprise as the direct impact it has, on real people, and in the real world.

Understanding experience

Everything going on in an enterprise has an impact on and is impacted by people’s experiences. When a person engages with a service, organization, brand, environment, or product—virtually everything visible that the enterprise produces—his or her experience is determined by the way those offerings are designed, and how well these designs address human qualities and context.

Experiences are highly subjective impressions, so that their nature, duration, and perceived quality vary from case to case, as does their individual relevance and impact in the enterprise. A single experience might take a few minutes, days, or even much longer—it depends on how long the person involved experiences its duration, and when a new experience begins. Regardless how well established and intense an enterprise’s relationship to a person might be, its appearances will only play a limited role in that person’s experience.

Example

Everything is experience—consider experience in the context of the previous examples:

An Enterprise Architecture function planning to redesign a company’s network architecture strives to ensure continuous availability of information, just as redesigning the logistics structure of a postal service has the goal of ensuring timely deliveries. Both are ultimately put in place to impact the experience of customers and employees.

Equally, a Branding initiative that positions an oil company as a responsible actor with regard to environmental issues is only visible in actual behavior and messages, again experienced by employees, customers and other stakeholders such as the public.

Also, when using a public transport service, people usually do not care very much about exactly how trains operate or are maintained, or how the transport company thinks about itself. They just want to get from A to B, comfortably, on time, for a fair price and without trouble. Using a train for this voyage is just a means to achieve the real goal, like visiting some friends.

People are having experiences with the visible appearances of the enterprise, everywhere and all the time. Every activity being carried out, every dialogue or decision by anyone related to the enterprise, qualifies as such an experience. In turn, every interaction, transaction, or other endeavor depends on the associated experiences of the people involved. Consequently, every offering made available to people addresses some kind of experiential concern.

Shaping experience

In business reality, most projects to transform the enterprise start with an experiential concern in mind — ultimately, some person or group is the target audience, the people who see and use the results. But instead of deeply exploring and analyzing this target experience to come to a design that fits, many projects lose sight of it early in the process. More often than not, an initially clear vision of the intended experience gets replaced by more and more product features together with technical considerations, derailing the original goal. Decisions are made without considering their impact on the experience, resulting in offerings that fail to adequately address the human qualities and context in which they are intended to be used.

To overcome this issue, decisions about and within transformation projects in the enterprise must be made with their experiential impact in mind. The design of a product or service itself is not what matters in the end, but its meaning and usefulness for the people it addresses. All technical systems and their interfaces, all products, artifacts, and visible elements, are just there to support that goal.

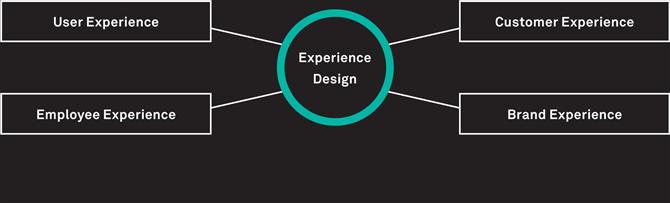

There is a range of emerging practices aiming to proactively understand and shape those elements that influence people’s experiences for the better. This activity is commonly referred to as Experience Design.

Experience Design

While everything, technically, is an experience of some sort, there is something important and special to many experiences that make them worth discussing. In particular, the elements that contribute to superior experiences are knowable and reproducible, which make them designable.

Nathan Shedroff

As explored in the previous part, design always seeks to have an impact on people’s thinking, feeling, or activities. As such, all design projects are transformations that seek to influence experience. The emerging practice of Experience Design is a process with a specific regard to this impact on experience, and differs from traditional design processes in that it puts a lot of effort in understanding the factors that make a great experience, and does not necessarily focus on a specific medium or technique.

In the enterprise context, Experience Design is a strategic instrument to establish and transform different kinds of relationships in the enterprise. It allows us to make design decisions based on a deep understanding of the influence a product, service, process, or other kind of solution to a problem has on the experience of its audience.

Design practices applied in this field are based on a deep understanding of the people you are designing for, their lives, characteristics, needs, and aspirations. Therefore, designers employ a human-centered attitude and use methods to engage in an active exchange with people. They employ extensive research techniques and attempt to develop empathy for the audience of a design, and to capture the emotional, aspirational, and contextual parameters that will make an experience a great and memorable one. They synthesize these findings into tangible prototypes of the final design that serve to validate and iterate it before anything gets actually implemented.

Depending on the individual context where it is applied, Experience Design addresses different types of experiences corresponding to different stakeholder relationships:

USER EXPERIENCE

looks at the way people use products, services, and other kinds of systems, and the quality of the resulting experience. Having roots in the digital realm, it focuses on technology, automated behaviors, and interfaces to complex multi-state systems.

CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

addresses commercial relationships in the enterprise, from being aware of a need to its fulfillment using a product or service. Having emerged from Marketing and Customer Service, the discipline focuses on customer satisfaction and retention.

EMPLOYEE EXPERIENCE

seeks to optimize the relationship between an organization and its employees by addressing their experiential needs and concerns along their career. This internal view of Experience Design is often seen as prerequisite for a good Customer Experience since employee behavior has a big influence on its success.

BRAND EXPERIENCE

has emerged from the more traditional practice of Branding, and attempts to look at a Brand from the perspective of the people addressed and transforming their experience when interacting with it.

Whether or not an experience with a product—anything an enterprise makes available is valuable and desirable to people depends on how well it addresses its audience and the context in which it is used. The better the enterprise deals with these factors, the more useful and delightful it becomes for the people it addresses:

HUMAN QUALITIES

how a design addresses a person’s perceptions, individual preconceptions and motivations, cognitive and physical abilities as well as attitudes, emotions, and affections. in the mind of people, it’s not the offering itself that counts, but the meaning, utility, and subjective satisfaction it adds to their lives.

CONTEXT

how an offering integrates in individual contexts of use, such as social structures and culture, physical contexts and individual situations. This includes elements such as language, symbols and codes, and behavioral norms, and whether people are in a private or a professional context, on the move, at home, or in the office.

Experiencing the enterprise

Seen from the perspective of a person, an enterprise can be described as a sequence of experiences. Everything going on in the enterprise ultimately impacts the experiences of those it is related to. For people, there are no business processes and technologies, just activities and tools they use to accomplish tasks. Content, information, and messages are merely means to inform choices and generate ideas or knowledge. Collectively shared identity, symbols and meanings inspire the emergence of culture and the creation of visible artifacts. These are produced and lived by people every day, becoming part of their experiences.

Every business objective or technical concern driving a project or process also can be expressed as an experiential goal of a specific stakeholder group or an individual. Successfully addressing its implications means influencing the experience of those people. It requires understanding their needs and aspirations to design a solution that helps them to achieve their goals.

Consequently, experience is a universal quality of the enterprise that impacts its relationship to anyone involved in its endeavors. Every project, every solution to a problem can be seen as part of a design to influence the experience of people, even if that experience is not consciously considered.

Experience Design applied in the enterprise context aims to proactively influence the relevant experiences of important stakeholders, equally applicable to a manager, a customer, or another person related to the enterprise. Using it successfully means making every factor of a design that influences the human experience a conscious, explicit decision. It is dependent on insights about the people you are designing for, and empathy is a prerequisite for developing this understanding.

Because of its broad scope, the results of an Experience Design approach are manifold. They range from the basic considerations of how a product or service integrates into a business strategy and meets human needs, to all the visible and usable elements that people interact with, like the conduct of a phone agent or the structure and appearance of a website or piece of software.

Example

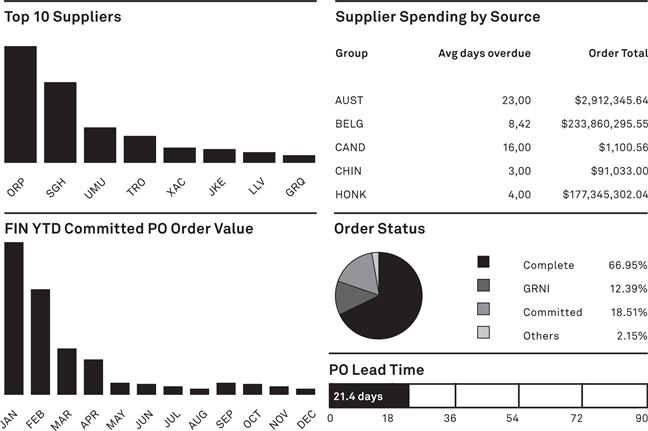

A manager responsible for a purchasing department of a large furniture company is a typical internal stakeholder. His or her job is to ensure availability and quality of materials, good prices and efficient supply chain operations. This translates to experiential goals such as the need to be informed about the market situation and prices, to be able to control and prioritize deliveries, and to establish a trustful working relationship to people inside and outside his organization. part of an Employee Experience initiative would be to find out about this experience, and designing everything to support these goals. A possible outcome could be a new reporting system, that delivers all relevant information for specific business roles in a dashboard.

A dashboard for a purchasing manager role, a specific part of a larger Employee Experience

Experience strategy

Because of this ubiquitous presence and fundamental relevance of experience in the enterprise, it is an important success factor for any organization, but largely ignored today. Deliberately addressing this factor as part of an Experience Design initiative can help organizations to gain competitive advantage by optimizing their relationship to people and the interactions with them.

On an organizational level, this can be achieved by formulating a globally applicable experience strategy. Such a strategy expresses what stakeholder experiences in the enterprise should be like, and guides all decisions about elements influencing these experiences.

The individual objectives and qualities addressed vary widely depending on the particular stakeholder relationship. An experience strategy targeted at your customers starts from an external perspective, the result of your work, and can be used to transform your organization to make their experience with your products and services a great one. This in turn might depend on an internal experience strategy that seeks to integrate people into the business, to give them what they need to do their jobs, to encourage their personal growth, and to inspire the working culture as it is lived every day.

Example

An interaction between a customer refueling a car at a gas station and the company behind that service usually lasts just a few minutes. It is embedded in a broader context of getting from A to B, and is just one element within that experience. The company has only that short time span to influence the customer’s experience.

A clerk at the gas station on the other hand shares the whole work day with that company, so that the influence on his experience is much higher. How well the particularities of his or her professional life are addressed is in turn influencing the experience of the customer.

Every person or group involved in activities in the enterprise is a stakeholder and potential target group, such as customers, suppliers and partners, or investors. The strategy may be applied to designs targeting very narrowly defined groups, limited to specific roles such as journalists or job candidates, or temporary relationships like visitors or readers. It may also attempt to very broadly influence the experience of everyone in touch with an organization. As it is being applied today, however, on the level of individual products, media, or services, Experience Design often falls short of its potential to have a real, business-critical impact on key stakeholder experiences.

Used on the enterprise as a whole, considering the experience quality allows us to understand it truly from the perspective of people, to explore their experiences and to design for them on a strategic level. Accordingly, it has to be used in conjunction with identity and architecture, to look beyond the individual experience at everything that constitutes the enterprise behind it.

Designing With Big Picture Aspects

After exploring the nature of enterprises in some detail based on universal qualities, it is important to point out again that all of them are describing the same things, just with a different focus. Identity, architecture, and experience are always there, in any enterprise. In other words, regardless of what element you are focusing on, it is still the same enterprise.

The Enterprise Design approach places design at the intersection of identity, architecture, and experience. Looking at the enterprise from these perspectives allows us to explore it as the context wherein a design initiative is meant to be applied, and as the system that it seeks to reshape and transform.

Considering the enterprise in such a way allows a design to act as the face of the enterprise to people. It can implement identity as a visible and approachable personality, turn architectural systems into usable and useful interfaces, and integrate these elements into people’s experiences.

A strategic design initiative is an attempt to align these qualities on a common course. It allows us to approach enterprise transformation processes from the outside in, starting with the intended experience of the people you are designing for, and subsequently influencing identity and architecture to achieve outstanding experience qualities.

Successfully designing for these qualities requires revealing them to people in many concrete manifestations, and orchestrating these solutions to play a meaningful role in people’s experiences. In the next chapter, we will continue with the individual elements that compose such manifestations at a more detailed level.

In practice, any transformation of one of the three qualities means also (often unknowingly) changing the others as well:

IDENTITY

![]() has to be perceived and lived as concrete manifestations in people’s experiences to come to life as shared ideas, which depends on behaviors, messages, and values expressed in business operations facilitated by architectural structures. In turn, experiences then shape these ideas and thus influence identity.

has to be perceived and lived as concrete manifestations in people’s experiences to come to life as shared ideas, which depends on behaviors, messages, and values expressed in business operations facilitated by architectural structures. In turn, experiences then shape these ideas and thus influence identity.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() describes a set of artificial structures, put in place around a group of human beings. In order to work, architecture has to reach out to people’s experiences, produce useful, valuable systems and interfaces, and address and implement identity in daily operations as concrete behavior, appearance, and communication.

describes a set of artificial structures, put in place around a group of human beings. In order to work, architecture has to reach out to people’s experiences, produce useful, valuable systems and interfaces, and address and implement identity in daily operations as concrete behavior, appearance, and communication.

EXPERIENCE

![]() can be seen as a short-lived, volatile space in which the results of architecture and identity become visible manifestations. Achieving a positive experience depends on the orchestration of these visible elements, in a way that makes sense and creates value for people, becoming a part of their lives.

can be seen as a short-lived, volatile space in which the results of architecture and identity become visible manifestations. Achieving a positive experience depends on the orchestration of these visible elements, in a way that makes sense and creates value for people, becoming a part of their lives.

In consequence, these qualities have to be addressed as one.

AT A GLANCE

Identity, Architecture, and Experience are aspects that capture universal qualities of any enterprise, touching everything it does, and being both the context of any strategic design initiative and subject to its outcomes. They determine how the enterprise is seen by people, how it works and achieves its goals, and the role it plays in people’s lives.

Recommendations

Use branding to transform your space of identities, designing brands to be dynamic platforms for social exchange rather than static symbols or messages

Develop a thorough understanding about the architecture that makes your enterprise work, and design to leverage and evolve the underlying structure

Base all design work on an experience-driven view, designing to enhance and reshape people’s experience and transforming the enterprise to match this

Use the Big Picture aspects to explore the enterprise as an overarching, dynamic ecosystem, and to put designs and their results into context

Case Study _ Ikea

IKEA’S ENTERPRISE

Becoming the world leader in functional furniture and accessories, combining design excellence with accessible pricing.

IKEA is not completely perfect. It irritates me to death to hear it said that IKEA is the best company in the world. We are going the right way to becoming it, for sure, but we are not there yet.

Ingvar Kamprad, Founder

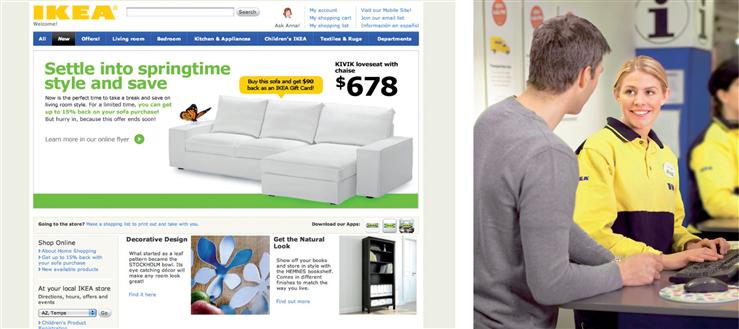

To many, IKEA is one of the world’s most fascinating companies. Founded in 1943 in Sweden, IKEA is today the world’s largest and most successful retailer in the furniture sector. In Europe, it is hard to find people who do not own at least some IKEA products, and for most students it seems to be the only place to go for equipping an apartment. When looked at from some distance, the company seems to be a stunning, well thought through system of elements that work together seamlessly. Everything fits together, and the elements of the enterprise work the same way across the borders of countries, languages, market segments, and cultures. Even across its stores, catalogue, and website, IKEA appears, communicates, and acts the same way. To achieve such a remarkable level of coherence, IKEA puts an equally remarkable effort into the systematic design of its enterprise, and excels at aligning different aspects and components on a common course.

IKEA perceives the design competency as the key enabler to its business, and applies it to everything that can possibly be designed, bringing together the purpose, values, and strategic goals of the group. The underlying IKEA concept is above all well thought through in its very details. It is a complex system of systems that took years to create, refine, and grow, which involved a myriad of conceptual design decisions and concrete transformation projects to get to its current state. In these efforts, the universal qualities of identity, architecture, and experience are addressed as the universal qualities behind the enterprise, reflected in everything the company is, says, and does. All operational and development activities contribute to embedding and sustaining these qualities in IKEA’s enterprise.

Identity

![]() The group’s enterprise identity is based on a strong core idea, which is communicated to every important stakeholder—clients, staff, suppliers and other actors in the enterprise environment. IKEA is following the vision of contributing to people’s lives by being your partner in making yourself a home. This idea is conveyed in a way that is simple and clear, and is represented in the variety of identities that the group creates and communicates.

The group’s enterprise identity is based on a strong core idea, which is communicated to every important stakeholder—clients, staff, suppliers and other actors in the enterprise environment. IKEA is following the vision of contributing to people’s lives by being your partner in making yourself a home. This idea is conveyed in a way that is simple and clear, and is represented in the variety of identities that the group creates and communicates.

A well-organized system of brand identities holds all of this together. The binding element is the IKEA brand, aiming to represent the sum of ideas, offerings, and values the company represents. Unlike other corporate brands in the consumer world such as P&G or Daimler, the IKEA corporate brand takes a strong position in every instance of enterprise-people touchpoints and is a focal point for IKEA’s consistent perception by people. The name is associated with the underlying concept, holds the different sub-brands and identities together, and is a vehicle to convey the company’s key messages to its audiences.

The ubiquity of the IKEA brand elements is visible in the application of its characteristics. Drawing upon the group’s origin from Smaland, IKEA appears openly Swedish, reflected in the choice of colors and other visual elements. But reaching far beyond the visual, this heritage is also represented in the choice of product identities based on terms from the Nordic countries. Each category draws on a different set of words, such as places, islands, or given names, sometimes with a semantic connection—for example, bathroom articles are named after Scandinavian lakes, rivers, and bays. This system gives the portfolio a coherent identity system, reflecting the brand’s characteristics and being easy to remember.

Moreover, this aspect of the brand is communicated by using speakers with a Swedish accent in advertising, and putting Swedish books into all shelves in the stores. Other values of IKEA’s brand identity are visible in every aspect of the business. All channels are seen as a means to convey and reinforce IKEA’s identity to all stakeholders. The uncomplicated, direct, and friendly appearance is reflected in all messaging, from official communications to error messages in their online kitchen planner. The culture promotes open exchange and empowers co-workers, making everyone a brand ambassador in communication and behavior.

IKEA combines self-service elements with a very personal communication style.

Architecture

![]() The IKEA enterprise works like a highly structured and thought-through system. The architecture considerations touch many different types of structures, but their interconnections reveal an overarching, enterprise-wide system of related system components and interactions. Key areas of IKEA’s architecture include the product portfolio, logistics and supply chain, finance and cost control, information systems, and operational business processes. Following the same core idea as the brand identity to be conveyed, this architecture is the prerequisite to execute on IKEA’s promise of excellent products at low cost.

The IKEA enterprise works like a highly structured and thought-through system. The architecture considerations touch many different types of structures, but their interconnections reveal an overarching, enterprise-wide system of related system components and interactions. Key areas of IKEA’s architecture include the product portfolio, logistics and supply chain, finance and cost control, information systems, and operational business processes. Following the same core idea as the brand identity to be conveyed, this architecture is the prerequisite to execute on IKEA’s promise of excellent products at low cost.

All products are based on a set of highly standardized parts and construction principles, allowing the group to benefit from huge economies of scale. Moreover, the assembly of the product itself is done by the customer, turning the principle of shared responsibility between the customer and IKEA into a collaborative model—we deliver all the parts, you build it yourself. Products delivered in parts can be optimized for efficient packing and transportation to the store network. This illustrates the idea of leveraging capabilities of external actors in the enterprise ecosystem, in this case the customer providing an expensive capability that is considered essential for a furniture business. To enable this shared model, the construction itself is simplified and described in visual manuals, again following strict standards to be easy to use. Besides the clear instructions, using visual explanation makes a single manual internationally applicable.

Customers encounter the same product multiple times across their journey.

With the same rigor, IKEA addresses architecture aspects related to physical, operational, financial, or IT structures. Money flows across a network of companies, separating the IKEA concept from the store operations and background processes. Core processes of production, logistics or sales are supported with a role-based and localized intranet to give every Co-worker the information and tools he or she needs. Customers are part of this system, contributing essential processes such as check-out, assembly, and home transport. Virtually everything is organized in a coherent way—this is visible in the universal information architecture underpinning the store layouts, web navigation menu, printed catalogue and IT systems everywhere in the world.

Experience

![]() Given the level of rigor and attention to detail IKEA puts into defining and applying its Architecture and Identity, it is easy to assume that these two elements are at the heart of their enterprise. In reality, however, they are merely the effects of designing everything coherently, and of the purposeful execution of a strong vision. And that vision is fundamentally about Experience.

Given the level of rigor and attention to detail IKEA puts into defining and applying its Architecture and Identity, it is easy to assume that these two elements are at the heart of their enterprise. In reality, however, they are merely the effects of designing everything coherently, and of the purposeful execution of a strong vision. And that vision is fundamentally about Experience.

IKEA defines its mission in terms of the Customer Experience it wants to create —contributing to people’s lives with its products, and partnering with customers to save money together. All elements of the enterprise contribute to this very well-defined experiential vision, applying design disciplines and related areas of creative transformation to make it reality. IKEA’s products are designed to include all functions of home furnishing, thereby providing a large diversity of styles, variants, and price ranges to have something for everyone. The high regard for product design at IKEA is visible in the systematic way of making items fit together in product families and combinations. The do-it-yourself philosophy is an essential part of this experience, turning the shortcomings of assembly and transport into a benefit, and making items cheap and easy to transport. Digital Self-Services make it easy for clients to transact with automated tools.

IKEA’s Experience Design efforts reach well beyond their products. The stores are designed around the activities of people who want to make themselves a comfortable place at home, facilitating a journey across a set of well-designed elements. This includes presenting products not as objects, but as cozy spaces with a character—connecting to people’s ideas about their own home and giving them inspiration, but also bringing together products in designed arrangements. With the well-known restaurants and cheap hot dogs, IKEA’s food division cares for people’s breakfast or lunch. The company also provides the Smaland day care during the stay, extending well beyond the core offering of furniture based on identified experiential concerns.

Design at IKEA centers on the customer, but extends to brand, employee and user experience approached in unison. In conclusion, it is not just Identity and Architecture producing these solutions—it is the other way around, making their strategy tangible as a global experience.