5

Anatomy

The aspects explored in the previous chapter form the basis to capture and describe what an enterprise actually is in the eyes of the people it is related to. They determine the overall subjective judgment from a human point of view—what it is about, how well it works, and to what extent it contributes value to people’s lives. Although they apply to the enterprise as a whole, having identity, architecture, and experience qualities, there is no single person who has a full view of their entire range. The enterprise as an entity is always quite fuzzy, without clearly defined boundaries and with a lot of inherent complexity and hidden parts obstructing the view.

While business success depends on the delivery of information and services to all of these critical stakeholders in the enterprise, their individual needs, aspirations and levels of insight vary widely. Anyone in touch with the enterprise experiences just a certain part of it, having a limited view on its architecture and a particular image of its identity. Consequently, overarching enterprise qualities manifest themselves differently in individual cases, and become meaningful for people only in the context of a specific relationship to the enterprise. In such instances, the visible and tangible elements of a relationship are perceived and put into use by people as part of their greater experience. They equally play a role in the larger architecture of enterprise operations, and they constitute identity and image. The strategic value of design comes from influencing and transforming these qualities from a human point of view. Key to this is the idea of the enterprise as a shared sense of purpose, with the goal to design every element that occurs in a relationship to contribute to that larger vision.

Example

consider the different stakeholders of an airline, each having a particular view and level of insight on the enterprise. A business passenger only experiences the flight service itself, having some superficial insight into the operations, but not into the background processes. The travel agent who booked the flight only experiences the web-based booking service, the experience with the airline being determined by a completely different set of factors. Inside the company, an operations manager may actually never experience these parts of the operations, but needs detailed data about the activities involved in their execution, and their profitability. in the enterprise as the wider environment, a staff member working for the airport again has a completely different view, facilitating a part of the operations as a service that the airport makes available to the airline.

Because of the specificity of every relationship, this involves looking at the details, and aiming to consciously shape the small elements that make a human interaction a positive and memorable one. It means a shift in perspective, from a macro-level of enterprise-wide qualities to the smaller scale, the enterprise as a microcosm. The elements portrayed in this chapter can be seen as constituent parts of an enterprise-people relationship, to be taken into consideration in any strategic design project.

The elements of enterprise relationships

In their bookPervasivelnformation Architecture, Andrea Resmini and Luca Rosati argue that today’s space of interconnected information systems, media, devices, and tools makes us constantly jump among the elements of a complex system of items and environments, resulting in dynamic and unforeseen behaviors. They describe such systems of connected elements as ubiquitous ecologies, as open systems of linked items in a space with physical and digital layers. Instead of being designed in isolation, elements which act as part of such a system have to support human activities that span all of them.

Classic design disciplines tend to deal with only a distinct and clearly separated subset of those items, visible in the dominance of specialized knowledge areas like web, interior, or editorial design. While such specialization is necessary to account for the particularities of a specific design medium, in a hypercon- nected world any outcome will just one part of a complex space of interconnected elements, with people using different subsets and configurations. It requires designing beyond separate categories, towards an integrative and hybrid approach to design. This is particularly true in the enterprise context, where so many people get in touch with each other, with various artifacts and procedures, interacting in so many different ways.

When approaching a wicked design challenge in an enterprise environment, the number of types of elements that may be relevant quickly becomes overwhelming. Depending on the chosen models, it might involve customer segments, business processes, activities and tasks, media and devices, digital information systems, and a multitude of other elements.

Similar to the universal qualities explored previously, these elements appear everywhere in the enterprise, at all levels and in any activity. Design initiatives can be seen as endeavors to positively affect the system of these elements: enhancing the relationship to certain actors by reaching out to them via relevant touchpoints, defining and delivering new and better services and content. Considering these elements explicitly in the design process is a way to broaden the view beyond the typical low-level focus on a particular artifact or medium, user, or target group, and to understand the broader context of the enterprise-people relationships behind the design.

As every item, be it product, piece of information, or service, is quickly becoming an ecosystem or part of an ecosystem, as such it has to be approached, designed, and consumed.

Andrea Resmini and Luca Rosati

in our consulting work, we found the following generic definitions to be particularly useful to approach a design challenge in the enterprise context with regard to its constituent parts:

ACTORS

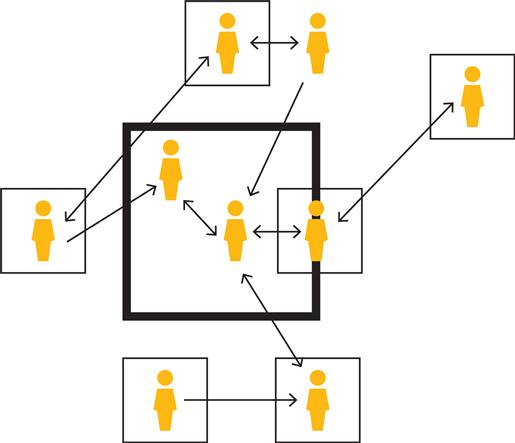

the various stakeholders related to the enterprise, addressed or impacted by its activities, or involved in their execution. ![]()

TOUCHPOINTS

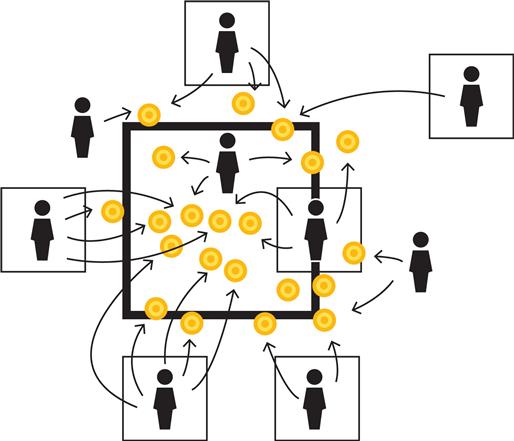

any moment in time and space a person gets in touch with the enterprise in some individual context. ![]()

SERVICES

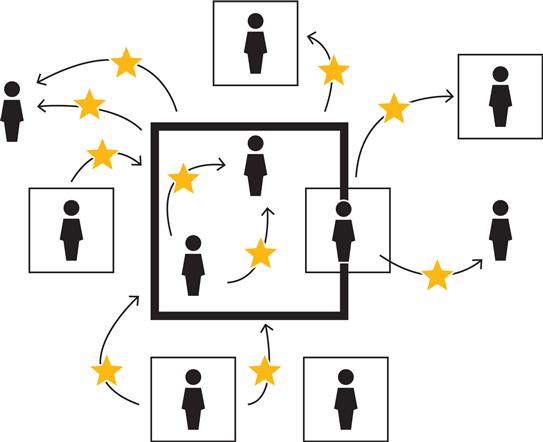

value propositions offered by the enterprise to customers and other stakeholders, and made available as activities and their results. ![]()

CONTENT

pieces of information or data being produced, exchanged and received in all kinds of communication processes in the enterprise. ![]()

On the following pages, each aspect is explored in more detail.

#4 Actors

Any design initiative, be it just a small website or a large program in the enterprise, ultimately targets people. The term actor refers to subsets of these people playing a certain role, reflecting a certain type of relationship — as users, customers, officials, or other types of roles that an organization may choose to explicitly address. Whenever a person acts and does something, he or she incorporates one or more of these roles, representing an actor of a certain type.

Because design is fundamentally about successfully addressing people, many design philosophies base the design process on their study and involvement, apparent in paradigms like user-centered or participatory design. In the enterprise context, designers find themselves facing a wide range of potential actors, so that the question of who to address can become quite difficult to answer. Depending on the level, context, and objective of a design initiative, the number and definition of actors to be taken into account vary widely.

Selecting and defining actors therefore is a conscious decision, and can be regarded as a fundamental act of designing. Based on this decision, the intended outcomes can be based on a strong understanding of the actors addressed and their role in the enterprise. This section introduces the concept of enterprise stakeholders as a basis to define, select, and address actors, and make this the foundation for all further design decisions.

From stakeholders to actors

Organizations are dependent on the societies in which they operate. These societies are the market for their offerings, their source for capital, labor, and knowledge, and the larger ecosystem they contribute to. Many management approaches focus on customers and shareholders as their most important stakeholders, yet other significant stakeholders include prospects, internal staff, suppliers, partners, or the public. Only recently businesses are shifting their attention to the full range of stakeholders, realizing that the concerns of those interest groups in the wider enterprise translate directly to their own concerns.

The concept of stakeholders was described by Edward Freeman in 1984, arguing that corporations are established and operated according to a set of social contracts, with the purpose to meet the expectations and demands of their stakeholder community. Every person having an interest—or a stake—in the enterprise, its goals, activities, or results, qualifies as such a stakeholder. According to Freeman, strong business performance depends on honest, open, and balanced relationships to all stakeholders, instead of concentrating too much on one particular interest group.

Stakeholders become actors addressed by an enterprise when they are consciously considered as people targeted by its outcomes. Generic concepts like user or customer often fail to address the particularities of a certain actor. People and their roles are so different that they have to be regarded as separate actors, to achieve a design that recognizes and enhances the relationship to them. The people viewpoint portrayed in the next chapter explores a human- centric design approach in more detail. Here the focus is on identifying the right people to address prior to exploring their context and characteristics.

Actors in the enterprise

Most classic design initiatives happen on a low level, where the scope and target group have already been decided and are part of the design brief, so that they target just one major stakeholder group. In contrast, taking an enterprise -wide point of view often results in a large number of diverse, interrelated actors to be considered.

All of these actors have different values, goals, and concerns to be taken into account. They reflect different roles in the enterprise, different levels of control and influence, and of insight and confidentiality. A business depends on the successful integration of many actors and their conflicting priorities and interests. Consequently, an enterprise design initiative needs to be aware of the stakeholders it considers relevant and addresses as actors. The space of actors to be addressed can become quite complex.

The definition of actors depends largely on the individual context. A single person might incorporate several actors, that are closely interrelated and depend on each other. There might be secondary actors, whose actions are mediated through other actors. Some stakeholders make use of automation to execute activities, so that there are machine actors, which act on behalf of the human actor behind them.

To develop a broad picture of the stakeholders in the enterprise and identify relevant actors to address by a design initiative, think of them in terms of the Big picture aspects:

IDENTITY

think of people, groups, organizations, or brands as images in people’s minds and participants in a dialogue, and consider all of them to be potential actors to involve. Design your own brands to be actors on their own, and match their role in that dialogue, including appearance, behaviors, and messages to convey. ![]()

ARCHITECTURE

think of people involved in executing business activities—communications, management, production, and delivery—and identify actors based on the different roles people play in those activities. Design enterprise structures to integrate these actors and accommodate their particular context. ![]()

EXPERIENCE

think of people interacting with the enterprise and the unique journeys they are taking. Each particular type of relationship or set of experience attributes is a potential starting point to identify and define a distinct actor. Design for actors that share a certain type of relationship, or experience a similar journey. ![]()

Role management

The West conducted a nuanced discussion of identity for centuries, until the industrial state decided that identity was a number you were assigned by a government computer.

Bob Blakeley

Enterprises today face the challenge of managing a wide range of actors, each with a set of roles attributed to his or her identity. People act in the context of job roles, customer segments, project teams, or other types of actor definitions. In order to address them proactively, they have to be identified both in automated architectures and manual interaction, and represented in artifacts and systems. This enables an organization to tailor its services, communications, and offerings to the people it is related to, taking into account the individual relationship.

The need to connect to various actors using digital systems, and to control the communication on a very detailed level has led to the emergence of a knowledge area known as Role or Identity Management, which focuses on identifying and managing how individuals access any sort of system. It is based on the practice of managing identities in digital directories, and using these definitions as a means to be responsive to the individual actors and people incorporating them. In practice, abstract actor definitions then translate into role concepts, groups and individual accounts, being used for identification, personalization, and customized service provisioning.

Applying Identity Management enables the enterprise to explicitly address actors, and to tailor its offerings and communications to the needs of individuals and groups. To be successful, such an initiative must not just tackle the inherent issues of privacy and data protection. The challenge of choosing the right entities, identification levels, and processes is fundamentally related to the enterprise-people relationship to be reflected in the managed identity space. The goal is to capture identities so that the enterprise can to connect people to brands, organizations, services, and each other in a meaningful way.

Managing roles and their identity typically involves multiple aspects, which together can be used to identify and address people in the enterprise:

DISTINGUISHING ENTITIES

a role is associated with an entity of some sort, which can be a person, a group, an • f organization, or even an abstract concept like a brand or a fantasy figure. The level of identification ranges from total anonymity to customizing on an individual level.

a role is associated with an entity of some sort, which can be a person, a group, an • f organization, or even an abstract concept like a brand or a fantasy figure. The level of identification ranges from total anonymity to customizing on an individual level.

ATTRIBUTING ROLES

information about identity can be attributed to physical objects such as a card, to data such as a password, or based on apparent attributes, like a person’s gender or the country a website is accessed from. Identities may be self-attributed, such as a user registration, or assigned by others. The attribution can be purely symbolic (like a logo), or include an identification mechanism.

information about identity can be attributed to physical objects such as a card, to data such as a password, or based on apparent attributes, like a person’s gender or the country a website is accessed from. Identities may be self-attributed, such as a user registration, or assigned by others. The attribution can be purely symbolic (like a logo), or include an identification mechanism.

MANAGING ACCESS

identities are used to grant and restrict access to virtual and physical spaces, setting permissions and privileges. It allows validating attempts to access a resource against an identity and its validity range.

identities are used to grant and restrict access to virtual and physical spaces, setting permissions and privileges. It allows validating attempts to access a resource against an identity and its validity range.

COMMUNICATING IDENTITY

identities are made explicit and visible in profiles and messages, and actively communicated. This is the basis for gaining legitimacy and managing reputation, and positioning identity as means to be perceived by others and create trust and awareness.

identities are made explicit and visible in profiles and messages, and actively communicated. This is the basis for gaining legitimacy and managing reputation, and positioning identity as means to be perceived by others and create trust and awareness.

Example

on the most global level, an organization must involve people acting as customers, suppliers, managers, shareholders or journalists. In a particular context, for example investor relations, these global definitions translate into more concrete actors, such as organizational and private investors, the company’s own financial managers, external analysts, or funds managers. Applied to a concrete outcome such as a website dedicated to the financial community, the choice and definition of actors might be used to conceive different sections suited to particular needs, or role-based access to offer personalized information.

Enterprise stakeholders can be classified into three major categories, all of them to be considered potential actors in the enterprise design:

TARGET GROUPS

people acting on a market the business addresses, such as prospects, customers, job candidates, or investors. The enterprise reaches out to them to place offerings and value propositions.

people acting on a market the business addresses, such as prospects, customers, job candidates, or investors. The enterprise reaches out to them to place offerings and value propositions.

AGENTS

people involved in core business activities, such as managers, staff, contractors, service, or outsourcing partners. The enterprise depends on them to operate and evolve the business.

people involved in core business activities, such as managers, staff, contractors, service, or outsourcing partners. The enterprise depends on them to operate and evolve the business.

ENVIRONMENT

actors in the wider periphery of interest groups, such as press, public, authorities, alliances, or neighbors. The enterprise strives to establish and maintain good relationships to them.

actors in the wider periphery of interest groups, such as press, public, authorities, alliances, or neighbors. The enterprise strives to establish and maintain good relationships to them.

Managing actor relationships

A challenge and prerequisite to design for actors is therefore to develop a broad view on stakeholders, and identify characteristics to differentiate them properly, from a major role on the enterprise level down to the individual role an actor fulfills in an activity. This in turn can be used by the enterprise to be responsive to the set of actors incorporated within an individual person. Many organizations struggle to find the right level of granularity to identify, define, and address their actors. The definitions must be fine enough to explicitly address an actor relationship, but also generic enough to achieve this within a reasonable amount of effort.

Working with the concept of actors is a powerful tool, and lets us be conscious of all the actors that an enterprise has to take into account. It allows us to explore their roles, relationships, and individual journeys when dealing with the enterprise. More than that, when applied to managed identities, designing with actors enables organizations to treat people individually, by delivering personalized and customized access channels.

Role Management is a field full of technical challenges—making identities work across several systems, ensuring data quality and security, and dealing with the inherent complexity of individual access levels. To deliver value to people, it must be based on a design that bridges the technical and the social sides. Questions related to confidentiality and information needs, data ownership and privacy, communicated and perceived identities, and reputation and trust are the drivers behind such a design.

The emergence of managed identities in information systems as profiles, permissions, and roles is merely a digital representation of a social reality that needs to be explored. Designing for a variety of actors therefore requires a multi-disciplinary and multi-faceted approach. An enterprise design initiative must be based on a deep exploration of stakeholder relationships, to come up with a set of actors that reflects their structure and relevance. Such a model of actors enables the enterprise to reach out to people with a tailored design, one that is suited to their particular relationship context, and built on managed identities.

The actual communication and interaction with actors usually happens through in a wide range of channels, both direct and mediated. A key challenge is to understand these connections, and to leverage them to reach out to actors.

#5 Touchpoints

Every time someone is in contact with an enterprise, this encounter is mediated by a touchpoint of some sort. Here, a touchpoint designates an interface between a person and an enterprise. The term refers both to the event itself and the physical context where it happens. Touchpoints facilitate activities such as using a service, receiving a message, or seeing an advertisement somewhere — therefore, they apply to brands, services, products, and other types of visible offerings made available by an enterprise to people.

The origins of the concept can be traced back to different practices, such as Service and Brand Management, multi-channel Marketing, and Customer Relationship Management. The emergence of new kinds of embedded digital media and the areas of ubiquitous and pervasive computing further widened the scope of the concept to include human-machine interactions across several devices. Today, the touchpoint concept is being adopted in many design-related knowledge areas, and is being used for all kinds of interactions. Depending on the individual focus, touchpoints might also be called situations, or interfaces. It is this universal applicability and wide scope that makes touchpoints such a useful concept in the enterprise context. It allows us to explore, improve, or completely redefine how a person experiences the enterprise in all its facets. This chapter explores touchpoints further, as the set of real-world links between people and the enterprise.

Mapping stakeholder journeys

The relationship of people and the enterprise can be described as a journey across touchpoints. This concept has been used for quite a while in the context of Customer Experience, but essentially applies to all types of relationships. The journey itself in turn largely depends on the individual relationship: some stakeholders, such as employees, regular customers, or shareholders experience a long and intensive journey, while others just briefly touch the enterprise. All of them can be quite important experiences—a brief encounter might even have more influence than a protracted episode, depending on the context. Looking at encounters enables us to optimize the individual touch- point, while dialogues and episodes are useful for the more intensive interactions. The lifespan view is useful for exploring how the relationship evolves over time, and how to engage people to expand it.

The focus of the touchpoint itself is the individual exchange, rather than the larger relationship or dialogue. It looks at a single instance for such an exchange to take place, focusing on the particularities of that individual context. But depending on what scale of journey you are focusing on, the touchpoint might play a different role. Consequently, the enterprise must see their touchpoints as individual links to people, while being aware of their role in the context of sequences.

Depending on the context, journeys across the enterprise involve different quantities of touchpoints, have varying durations, and can be seen as different levels of the underlying relationship:

ENCOUNTERS

or single touchpoints, are very brief and isolated moments where a person is in contact with the enterprise.

or single touchpoints, are very brief and isolated moments where a person is in contact with the enterprise.

DIALOGUES

or short term journeys, are interactions with a person or a system of some kind, but usually without major interruptions and lasting from minutes to hours.

or short term journeys, are interactions with a person or a system of some kind, but usually without major interruptions and lasting from minutes to hours.

EPISODES

or long-term journeys, are part of a larger activity, and involve multiple dialogues or encounters with interruptions in between. They can last from days to weeks.

or long-term journeys, are part of a larger activity, and involve multiple dialogues or encounters with interruptions in between. They can last from days to weeks.

THE RELATIONSHIP LIFESPAN

or overall journey, covers all touchpoints between a person and an enterprise as a whole. It reflects the entire relationship as a sequence of exchanges.

or overall journey, covers all touchpoints between a person and an enterprise as a whole. It reflects the entire relationship as a sequence of exchanges.

Example

coming back to the example of booking a flight for a business trip, the first encounter could be an advertisement seen somewhere, reading about an airline in a newspaper, or having a flight popping up in an online search. The activities involved such as booking a flight and the activity of travelling itself could be seen as dialogues. this series of dialogues then represents an episode, from awareness to service delivery. in the long run, the relationship lifespan captures aspects like overall customer satisfaction addressed with loyalty programs, which in turn create new touchpoints and dialogues. To switch perspectives to other stakeholders, you might think of the journeys of the traveller’s personal assistant booking the trip, or the one of a commercial pilot, all actors essential to the airline’s business success.

Designing with touchpoints

Designing with touchpoints always involves a strong sensory dimension, because they will be perceived by people. Depending on the nature of the touchpoint, that might involve designing with visual, tangible, or auditory elements. More deeply, the touchpoint exchange also involves intellectual and emotional qualities, if it enables understanding, usage and utility and helps to achieve a good experience. This requires different design aspects to work together to form a coherent whole. The result of designing for a touchpoint can be a tool, environment, or information medium, or any combination.

Used for design work in the enterprise, the concept of touchpoints is a very valuable tool for analyzing the contexts wherein an outcome will be applied, and demands a strategic choice of the touchpoints to consider and explicitly address. Because of their nature as interconnected elements, considering touchpoints makes the designer conscious of the different aspects of the larger system that the design controls, influences, and integrates in. Design that considers the journeys of different actors across touchpoints inevitably also involves the transitions and relations between touchpoints, bridges that enable both linear conversion and non-linear jumps.

In their book This is Service Design Thinking, Marc Stickdorn and Jakob Schneider compare the idea of such journeys to other forms of time-based media, such as music, movies and stage plays. Multiple touchpoints are experienced as a sequence of elements, much like an animated movie is made out of static pictures. To explore the particular qualities of such a journey, it can be useful to look for the typical characteristics of music or film—rhythm and melody, message and drama, in order to capture and influence the experience of a certain actor.

Touchpoint orchestration

The term orchestration with respect to touchpoints was used in 1984 by Lynn Shostack in her concept of Service Blueprinting, and implies that it deals both with the analysis and evaluation of existing touchpoints, and with the transformation, creation, and alignment of new or changed touchpoints. It borrows from the world of music, emphasizing that different touchpoints work together like musicians, to bring a service to life.

In his book Brand-Driven Innovation, Erik Roscam Abbing defines the practice of touch- point orchestration in more detail. It breaks the journey of actors into different steps and contexts. Depending on the nature of the touchpoint, it allows us to repartition the tasks of designing the details across different design professions, while being conscious of the interrelations between those individual contributions. It permits designers to innovate and bring the brand promise to life at individual touchpoints. Although a dedicated approach to touchpoint orchestration is a fairly young professional practice, it will have to become part of the toolkit of anyone dealing with design on a strategic level.

in the literature on the subject of Touchpoint orchestration, practitioners are particularly interested in identifying touchpoints that stand out for people in some way:

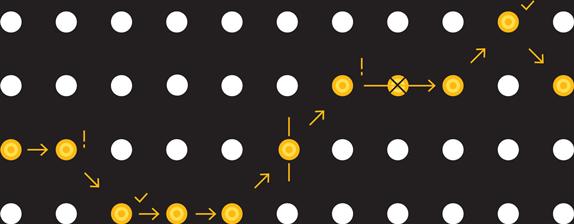

CRITICAL INCIDENTS

![]() touchpoints that make a strong impression and result in a memorable experience, both in a positive way (pleasure points) or a negative way (pain points).

touchpoints that make a strong impression and result in a memorable experience, both in a positive way (pleasure points) or a negative way (pain points).

MOMENTS OF TRUTH

![]() touchpoints that provide an opportunity for the enterprise to achieve an outstanding performance in an exchange with an actor, leading to a better relationship.

touchpoints that provide an opportunity for the enterprise to achieve an outstanding performance in an exchange with an actor, leading to a better relationship.

CONNECTION POINTS

touchpoints that are used to transition from one state into another, taking the journey on a new level, such as a customer conversion or a switch to another medium.

touchpoints that are used to transition from one state into another, taking the journey on a new level, such as a customer conversion or a switch to another medium.

REDUNDANT POINTS

![]() touchpoints that could be avoided, unnecessary steps that could have been saved, or encounters that place needless burdens on the actor.

touchpoints that could be avoided, unnecessary steps that could have been saved, or encounters that place needless burdens on the actor.

The enterprise as a contextual universe

The idea of touchpoints is fundamentally about the context of experiences. Any design, at any level, integrates into a given context, and creates new contexts with its perceivable outcomes. This makes them comparable to the physical places the enterprise makes available to facilitate its exchanges with people.

Many touchpoints actually happen in physical environments, such as stores and offices, while others exist in a virtual space and can be reached using communication technology—from calling a phone line to a web-based project space. In the enterprise, touchpoints therefore correspond to the physical and virtual places people use to get in touch, and the context they provide to the exchange. It is where prospects become aware of offerings, buy or use them, where employees work, meet, exchange, and collaborate—virtually and physically, along shorter and longer journeys.

Designing for enterprise touchpoints involves exploring the community of actors, to bring them together in shared contexts. It also implies a careful prioritization to determine the relevant subset, and striving for convergence and divergence where it makes sense. This enables the organization to introduce new touchpoints and remove weak ones, to make them work together as a strong chain. In that sense, the concept of services is useful, since it focuses on the greater purpose beyond orchestration.

The quality of actor journeys across the touchpoints with your enterprise usually varies widely. this has to do with the complexity involved in addressing so many different ways to exchange, and varying degrees of understanding about the touchpoints’ characteristics:

INFLUENCE

on some touchpoints, the organizations can exercise full control, such as their corporate stores. In other cases, like a social network, the control is much weaker. In other instances, like press articles, there is little influence at all. ![]()

MATERIALITY

a touchpoint may be primarily of virtual or physical nature, of a mixture of both. It involves engaging different senses, like the smell of a store or a product, or a specific way to interact with a interactive system. ![]()

CONNECTIVITY

touchpoints may appear to be rather separate, or deeply embedded into a network of other touchpoints. They might connect various people and enable social interaction or be used by a single person in isolation.

In the enterprise context, touchpoints can be described as exchanges incorporating the universal enterprise qualities towards actors. To explore them further, look at them in terms of these qualities:

IDENTITY

the way you express your identity at touchpoints with actors as perceivable symbols, apparent in artifacts, messages, and behavior. this translates to the sensory, behavioral, and communicative implementation of brands in individual instances. ![]()

ARCHITECTURE

the way you consider touchpoints in the architecture of your enterprise, plan to use them to deliver information and value, and make them part of your operations. Architectural elements are used to implement touchpoints as communication channels.![]()

EXPERIENCE

the part the touchpoints play in the individual experiences of people related to the enterprise, and the way you attempt to influence that experience by redefining their journeys. This is the basis to decide what touchpoints to consider and address in a design.![]()

#6 Services

An idea which has gained a lot of traction in recent decades is the notion of services as the basis for business activities. It is reflected in the idea of a service economy— a constantly expanding business sector that dominates Western economies—and also a development where the service part of more traditional business models becomes a more important and relevant aspect.

There are numerous examples for the domination of the service paradigm in today’s markets. Beyond purely service-based industries like finance, logistics, or the public sector, other economic sectors are adopting service orientation as a way to change and extend their offerings. Hardware and software providers turn their products into platforms and markets for virtual goods—by establishing service ecosystems around traditionally manufactured products, by integrating service provision to complement a product, or by switching to a rent model. In any case, the offering shifts from a transfer of ownership to an integrated product-service continuum that focuses on an ongoing managed relationship instead of a one-time sell.

Another case of service orientation applies to the field of information technology. The idea of Service-Oriented Architectures (SOA) describes the concept of breaking big information systems into a network of small, connected services. Following that technical definition, a service executes a single function that may be needed to run an automated part of a larger business process. It makes this function available to other services, so that an entire automated process can be executed by a chain of service interactions. Compared to traditional applications, services in an SOA can be recomposed in new ways more easily, reused for new purposes, and replaced with better or different services when the need arises. This is the basis for all the automated services offered by technology companies, both large and small, now commonly referred to as being in the cloud.

The different views on services mentioned above demonstrate a large variety of different concepts and definitions. Regardless of the respective idea and focus, all of them reflect the same basic idea of encapsulating and specifying a certain activity, be it automated, manual, or both, to generate a benefit for some actor other than those providing the service.

By that definition, services can be described in terms of the benefits they realize for an external beneficiary, the service consumer (result-oriented view). Those benefits and the way they are produced can be subjected to planning, analysis, engineering, and design approaches, undertaken by the service provider to accomplish the best possible service.

This interpretation of services as benefit generators makes them a valuable concept in any strategic design initiative, aiming to deliver a benefit to actors in the enterprise across different touchpoints. They are dynamic processes, being produced at least to some extent the same time they are consumed. To develop a more detailed understanding about services as design elements, you have to look at their inherent characteristics.

The service qualities described here allow an understanding of the large variety of forms services can take. In terms of the qualities, any combination is possible—services directed at people or machines, services with any degree of automation and visibility, isolated or highly interdependent services. In reality, there are few examples of extremes, and many services show mixed characteristics.

The attributes of an individual service have great impact on its success in delivering the benefit it was created for, and can make it work or break in certain situations. While automation and the use of technology are critical success factors for many services, it is important to keep in mind that any machine involved works on behalf of a person, so that the final actors appearing in a service are human.

Example

To illustrate these further, think of these qualities as they become apparent in gastronomic services. Depending on the individual business model, you might find yourself dealing with people or machines, have little choice, or be engaged an extensive dialogue. A restaurant can be based on fast automated delivery of standard food like Mcdonalds, or careful preparation of hand-made food relying on the chef’s distinctive talent.

The enterprise as a service delivery system

The notion of services has proven quite valuable as a paradigm to design complex socio-economic and socio-technical systems, mainly because the inherent people, business, and technology aspects are all very present. This makes the concept of services also applicable beyond classic service offerings targeted at customers, to the enterprise as a whole. Essentially, all business offerings and activities considered part of the enterprise can be captured in terms of services. The concept is useful as a way to think about the enterprise and what it does to achieve stakeholder benefits.

Services can be understood by a set of distinct qualities, although they vary widely depending on the individual case. Applying Lynn Shostack’s model, these qualities allow us to make conscious design decisions, and to develop a blueprint of the service production process:

INTERACTION MODE

![]() the type of interaction between service consumers and service providers during the course of the service, represented by activities that involve customer tasks. Variants range from personal services delivered by people to people, to automated services where both actors are represented by machines, and various mixed modes. A very common mode is self-service, where the service consumer interacts with an appliance that acts on behalf of the service provider.

the type of interaction between service consumers and service providers during the course of the service, represented by activities that involve customer tasks. Variants range from personal services delivered by people to people, to automated services where both actors are represented by machines, and various mixed modes. A very common mode is self-service, where the service consumer interacts with an appliance that acts on behalf of the service provider.

CONSUMER VISIBILITY

the degree of visibility to the service consumer of activities involved in service production. Extremes are back-office services that consumers are completely unaware of, and those services with a great involvement of a front-office, dependent on a lot of exchange between provider and consumer. Services can be delivered as a black box whose inner functions are hidden from the consumer, or completely transparently, or anything in between.

the degree of visibility to the service consumer of activities involved in service production. Extremes are back-office services that consumers are completely unaware of, and those services with a great involvement of a front-office, dependent on a lot of exchange between provider and consumer. Services can be delivered as a black box whose inner functions are hidden from the consumer, or completely transparently, or anything in between.

It’s no surprise that companies outside the economic service sector explore services as a paradigm to deliver experiences, bring identity to life, and connect products and environment in a meaningful way.

Erik Roscam Abbing in Brand-Driven Innovation

PRODUCTION AUTOMATION

the degree to which the production of a service is automated using information technology or other means. There are services completely delivered by machines and computers, while others depend on a large degree of manual work to come to life. Many services designed for mass consumption today rely on a mixed strategy: as much automation as possible for the standardized delivery, while relying on manual interventions to deal with exceptions.

INTERDEPENDENCE

services are never provided or consumed in isolation, but as part of a larger environment of activities, interactions, and other services. This makes them interdependent with elements outside their own scope and reach, and beyond their control. while services can be designed to operate as independently as possible, at the very least they depend on their consumers to be successful. in other cases, services rely heavily on their integration with an outside context.

In his book The Service-Oriented Enterprise, Tom Graves argues that you could be rethinking any activity in the enterprise as a service. Such a definition would include services provided to customers, internal services such as HR and the canteen, but also yearly audits or broad business activities such as Marketing, or management in general. Services add the time dimension to the relationship between enterprises and the actors they address, making their offerings and activities part of their larger journeys across touchpoints. They are the conceptual frame that turns these touchpoints into the service-related business events that appear everywhere in the enterprise, in all exchanges with actors. They bring the enterprise to life—including the architecture used to deliver the service, the identity conveyed with it and the effects on people’s experience.

Designing with services

In the context of an enterprise design initiative, services can be used to express what an enterprise offers—or should offer—to its various stakeholders, which take the role of the consumers of a particular service. It allows us to define the final benefit, the value an enterprise realizes for people. It also helps to avoid losing sight of this goal because another intermediary goal gets in the way, such as the manufacturing of a product, or the construction of a machine.

A design approach applied to services has to be cross-disciplinary and adaptive to the individual context in which the service is produced and consumed. Depending on that service context, it might require a wide range of different business, design, and engineering skills to define the service offering, involving physical environments, interactive media, or communications—the scope covered in the area of Service Design.

A service-oriented view on the enterprise can be applied to virtually any offering, capturing it as the set of purposeful activities it carries out to provide benefits to its actors. Within this context, service design is a powerful thinking tool for complex relationship challenges, because it applies a holistic view on the service to be designed, starting with people’s experiences. Service production and consumption are the exchanges between actors in the enterprise, represented by the content being exchanged across touchpoints.

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!

Theodore Levitt

services are omnipresent in the enterprise, since they are the activities that allow delivering the stakeholder benefits that the organization has been created for. As with actors and touchpoints, consider the role services play in the manifestation of universal enterprise qualities:

IDENTITY

in terms of identity, services are instances of organizational behavior planned in advance, and executed to deliver a benefit to stakeholders. services make an organization act — think of it like a person serving other people in the enterprise, as the proactive implementation of your brand, both shaping and shaped by behavior.![]()

ARCHITECTURE

services are connected to the architecture of an enterprise in two ways: they are dependent on the structures as a service delivery system, and in turn become a part of that structure themselves. service architecture refers to the way a service is implemented and operates as part of the business activities.![]()

EXPERIENCE

all services contribute to the goal of achieving a benefit for some human actor in the enterprise, resulting in a particular service experience for the consumer. But the experience quality also applies to actors involved in the service provision, both success factors usually being quite closely related and dependent on each other.![]()

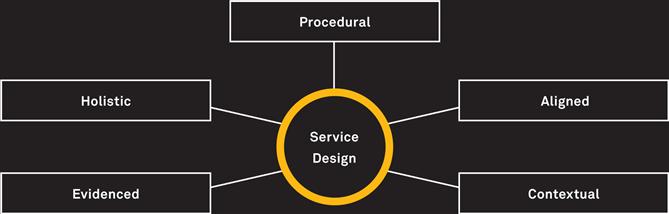

Service design

The emerging approach of Service Design aims to respond to the specifics of designing services, regardless of their individual implementation in artifacts, messages, and environments. It concentrates on the specific characteristics of service provision and consumption, and the aspects of services as procedural designs involving both tangible and intangible aspects. Service Design embraces the difficulty of applying a design approach to something as complex and hard to outline as services.

Service Design is a cross-discipline approach uniting many design skills involved in conceptualizing, implementing, and delivering services. The service design itself happens on a meta-level, using methods and approaches from related disciplines and adding them to the blend. Designing services involves a high degree of variability and ambiguity, because the end is unclear at the beginning of such a project. Moreover, unlike manufactured products a Service Design cannot be completely prescribed—they come into existence at the same time they are provided and used. It is this comfort with ambiguity, combined with high-level thinking, that makes the Service Design approach so well suited for strategic design in the enterprise.

practitioners are applying an inclusive and open view:

HOLISTIC

designing services involves a mindset beyond predetermined media of established design disciplines. It requires thinking of the design as a sequence or process, as a system with states and layers, with parts delivered by automated machines as well as human elements, and considering this to be part of a larger environment. It also takes the wider cultural and social aspects into account.

ALIGNED

because of the important human element in the creation and delivery of services, service Design needs to consider every person involved in service provision and consumption, both as stakeholder and as part of the system to be designed.

EVIDENCED

any artifact that appears as part of how a service is viewed is considered with regard to the wider role it plays in the service choreography, instead of as an isolated entity. service Design makes use of prototyping to capture these tangible evidences of a service.

CONTEXTUAL

because services are experienced by people in a certain spatial environment (known as Servicescape), service Design is based on the physical context and environment in which it happens.

PROCEDURAL

it uses time-based techniques such as role-play or staging to capture service consumption and provision as a sequence over time, and specifies processes of interrelated activities performed in a certain sequence. services are defined as scripts or scenarios, together with environments and artifacts.

#7 Content

Content is not a feature.

Kristina Halvorson

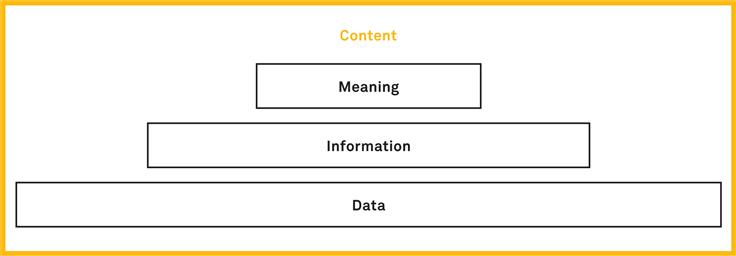

The term content is widely used today in various professional areas, such as web communications, social media, and knowledge management. In all these contexts, it refers to any piece of information or data that is contained in some sort of medium, exchange, or system, and made available to people. It covers all messages, documents, and other types of packaged information being produced and exchanged in some sort of communication process.

Because of the sheer mass of data and content appearing and the difficulty of working with it, the ways to manage content for websites have made significant progress in the past two decades. Based on the idea of separating the content from its delivery and presentation, there is a whole industry that specializes in storing, managing, and delivering content in Content Management Systems (CMS). Building on the same idea, managing content in the enterprise is an even more profound challenge. Large organizations today use sophisticated Enterprise Content Management (ECM) systems to control and use all their content, including systems for document and records management and data warehouses, to control and use all their content. These systems are used in professional areas like Knowledge and Information Management, and form the basis for any managed use of content in the enterprise context.

However, these approaches are based on the assumption that there is a mass of content that needs to be managed and governed. To understand content in the context of strategic design in the enterprise, we have to take a step back and look at the overall nature of content in business, and the role and purpose it fulfills for people in touch with the enterprise. This detailed understanding allows us to create and sustain content that is meaningful and useful to these people, and is a valuable business asset to the enterprise.

Content as a business asset

Based on such a comprehensive view, all bits of information that appear in a business context can be considered content, and potentially as a part of the efforts to manage, develop, and utilize it. It includes documents and files, messages and conversations, and all sorts of data stored in databases or other kinds of repositories. It can be calculated numbers and structured data, but also any kind of textual, visual, audio, or video information.

In an organization, content elements are assets that are vital for its success, both for internal activities and the relationship to the outside world. On the inside, it is the intellectual capital that supports all kinds of business activities with context and insights, touching every department and role. On the outside, it is everything the organization communicates to its external stakeholders.

The example illustrates the wide range and tremendous amount of content produced in a typical business environment. The different types, formats, scopes, and media reflect the various purposes content is produced for, to play some role in a communication process in the larger business context. How well an individual piece of content fulfills that purpose depends on its ability to create meaning for those being addressed.

Example

Think of information generated around the products of a car maker. The production process comes with internal policies, guidelines, procedure descriptions, and information about the products themselves, stored in some database used for internal purposes. The same information is partly also used on the corporate website or in catalogues, together with written text, photos, videos, tables, and figures.

Moreover, products ship with technical manuals, and are subject to advertising campaigns and promotion, again producing content. They are referred to in press releases and communications, but also in transactional messages around the sales process such as phone conversations or emails. There is content produced by the carmaker itself, but also a whole sphere of media coverage, conversations in social media, and descriptions of cars on trade platforms. In the car itself, there are signs and signals, symbols and labels, content produced to help drivers use it.

To have an impact on the daily business, content needs to be defined first and foremost in terms of the meaning it creates for its audience. Meaning is inferred not from the content itself in isolation, but also from the context wherein it is perceived by people. That context includes what the content is about, who the originator and recipients are, as well as the chosen medium and structures to communicate it.

Beyond the pure data, content is a representation for real-world objects and activities. Think of financial values represented in an invoice or an account statement, representing the transfer or possession of actual money—having as much “real” impact as doing the same transaction with physical banknotes. For people dealing with content, these referents therefore become a part of the things contained in the medium, and are subject to exchange processes together with the information or data portion of the content.

Therefore, content can be seen as the substance of any exchange going on, in every business activity. Anything that generates meaning for the actors addressed by an enterprise can be considered part of its content, regardless of the medium or format, amount of data, or level of editorial care. Turning data into content meaningful for stakeholders therefore requires looking at the roles and functions of content in the enterprise, the larger context where it is put into use.

The purpose of content in business contexts can be described using three levels of usage, loosely inspired by the Data /Information /Knowledge/ Wisdom hierarchy (DIKW) known in information science:

MEANING

is the content interpreted and implicitly applied in a specific context, used to generate knowledge through validation, inspiration or reasoning. It is used to form opinions, make decisions, and guide actions.

is the content interpreted and implicitly applied in a specific context, used to generate knowledge through validation, inspiration or reasoning. It is used to form opinions, make decisions, and guide actions.

INFORMATION

in this definition is the level where content is made explicit to deliver insight to people, by informing people about something. on this level, content needs to be expressed and presented in a way that enables understanding by the target audience.

in this definition is the level where content is made explicit to deliver insight to people, by informing people about something. on this level, content needs to be expressed and presented in a way that enables understanding by the target audience.

DATA

is a group of attributes and their values made explicit on the lowest abstraction layer. On this level, content is being captured, processed, consolidated, and stored. It is about getting the right data, and improving its quality or consistency to prepare for a specific use.

is a group of attributes and their values made explicit on the lowest abstraction layer. On this level, content is being captured, processed, consolidated, and stored. It is about getting the right data, and improving its quality or consistency to prepare for a specific use.

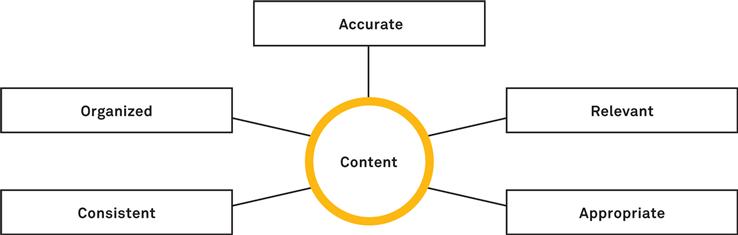

Content strategy

Whether content fulfills its purpose depends on a wide range of strategic decisions, from topics and messages to the tools and processes used to acquire, create, and manage it. content strategy helps to make these decisions, in order to manage the creation, use, and lifecycle of all kinds of content.

It is a young field that follows the idea that what enterprises should be after is not more content, but the right content. content strategy is about understanding, strategizing, planning, and controlling how, when and why what content is being generated. content strategy professionals turn the set of core topics and key messages into a coherent approach, analyze and audit current content, and use these insights to formulate goals, and to define structures, formats, attributes, and styles.

From a content audience point of view, content strategy addresses the quality aspects of message and meaning, format and type, as well as access and media in a holistic fashion. To achieve such high quality content, practitioners develop a plan for the use of tools and workflows for content creation, acquisition, publishing, management, and governance. Although it touches technical questions on content interoperability, storing, aggregation, and transformation, these aspects are merely means to an end: achieving better content with less effort.

Moreover, putting a content strategy in place helps organizations to communicate in a world where the line between authors and readers, or producers and consumers, becomes blurrier and blurrier. Actors in the enterprise are now contributing participants in content ecosystems, and actively produce new or repurpose existing content by composition or commentary. To leverage and benefit from social content as a strategic resource, it has to be addressed with a strategy.

Content strategy can be universally applied in many areas in the enterprise, including communications, Knowledge and information Management, social media and collaboration. with the ever-growing amount and influence of information, its greatest potential lies in the application to all content in the enterprise.

A content strategy typically consists of several aspects:

CREATION

generating, structuring, and formatting content; defining its attributes, styles, and ownership depending on the individual context.

COMMUNICATION

defining key topics and messages, communication channels and comprehensiveness; ensuring findability, usefulness, and consistency across all instances.

GOVERNANCE

auditing and cataloging content; publishing workflows, editorial calendar and continuous improvement; managing the content lifecycle, transformation, and aggregation.

Enterprise content

Content is the basis for all understanding, collaboration, and decision making in the enterprise. It is the substance in all exchanges between the different actors, and across all touchpoints. It is part of any service or offering, and is both by-product and resource of any activity. As a concept, it enables the capture of any kind of encapsulated information, regardless of its individual purpose, format, or origin. Anything the enterprise makes available to people related to it depends on the quality of the content used and generated.

Today, content elements are only seldom regarded as assets for a potential enterprise-wide use. It is much more common to produce or acquire content in an isolated fashion in various places and groups across the enterprise. Even the content of a single department or around a single service is often generated in isolation, for a particular purpose or medium. This is particularly visible in the mass of potentially relevant content lying asleep in archived email threads.

The effects of this lack of coordination and alignment are not only the inefficiencies of redundant content produced and maintained in parallel, but also inconsistency for the actors addressed with a particular content. Key to achieving high quality content is to address it as part of a strategic enterprise-wide design initiative.

Designing with content

More than just the technical issues of storing content in a flexible way, a design addressing content on a global level has to make a wide range of strategic design decisions. The objective of design with regards to content must be to enhance the meaning of a content element. Content must be considered as the substance of services provided for and by enterprise actors across all touchpoints, striving for high quality content in every instance.

Applying content strategy globally in today’s world of constant content production and exchange offers a tremendous opportunity to organizations. Thinking about content strategically enables us to explore and leverage synergies and cross-content effects to get key messages across to all audiences in a coherent way. Moreover, it permits us to reduce cost of creating, managing, and distributing content through reuse and alignment.

To better understand the role of content in the enterprise, think of it in terms of the universal enterprise qualities:

IDENTITY

![]() the messages you convey in communication processes toward actors in the enterprise. It describes what a brand says, how to engage audiences, how people are involved in content creation and dialogues. Content production as well as its tone and style reflect the organizational culture, and constitute identity.

the messages you convey in communication processes toward actors in the enterprise. It describes what a brand says, how to engage audiences, how people are involved in content creation and dialogues. Content production as well as its tone and style reflect the organizational culture, and constitute identity.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() the operational side of the enterprise as a working system depends on communication processes among its constituent parts. Content in that sense is about the formal structures put in place to create, manage, analyze, and publish information, and how the enterprise depends on the exchange of content elements.

the operational side of the enterprise as a working system depends on communication processes among its constituent parts. Content in that sense is about the formal structures put in place to create, manage, analyze, and publish information, and how the enterprise depends on the exchange of content elements.

EXPERIENCE

![]() the way a person receives, perceives, and understands content to derive meaning from it in the context of his or her particular experiential context. It refers to the subjective nature of content, its individual quality and success depending on the interpretation of a person and the meaning it creates in that context.

the way a person receives, perceives, and understands content to derive meaning from it in the context of his or her particular experiential context. It refers to the subjective nature of content, its individual quality and success depending on the interpretation of a person and the meaning it creates in that context.

High quality content in the enterprise can be characterized by a set of characteristics that make it meaningful for people exposed to it:

ACCURATE

content elements should be current, not contain false or misleading information, and convey these messages clearly and unambiguously.

RELEVANT

content elements should be valuable and useful for their audience and be usable by them to achieve that purpose.

APPROPRIATE

content elements should be adaptive to the individual use context and media, and convey messages in a comprehensive, well-presented, and digestible way.

CONSISTENT

content elements should fit into the larger system of information exchange, integrative and coherent with complementing or related content elements.

ORGANIZED

content elements should be easy to find and self-describing, as well as efficient to produce, manage, organize, and reuse.

Designing with relationship elements

The aspects explored in this chapter are the building blocks of an enterprise-wide design initiative. They are modular, interconnected parts of any interaction with a system which constitute the underlying relation. Organizations provide, reuse, and recombine relationship elements to shape and transform their enterprise. They are the building blocks of the enterprise as a system of relationships.

The result is a constant exchange: the enterprise makes services available as content exchanges via touchpoints, to play a role in the journeys of actors. In that dialogue, elements are always co-produced with the people you address, in the moment they come to life. Engaging in a dialogue with the enterprise requires embodying a certain role, and equally there is no service without interaction between provider and consumer, no touchpoint without an environmental and physical context, and no content without meaning for someone. Therefore, a design can only partially control and predict the configuration and implementation of relationship elements in an individual exchange.

In the enterprise, these elements appear as fractal, recurring structures, regardless of what level you look at. They play a role in human interactions with small systems such as websites, but also in large scale systems such as entire markets or the criminal justice system. As such, they form a hierarchy of larger and smaller elements that have to be orchestrated for a design to succeed on the enterprise level. They are intangible in terms of the means of bringing them to life, but also appear as tangible, visible elements which are perceived and used by people.

Unlike the Big Picture aspects described in the previous chapter, relationship elements can be actively incorporated into a design initiative, and addressed with a transformation. They are among the topics most design initiatives address in one way or another, although sometimes in an implicit or accidental way. When designs get more strategic and large-scale, it is quite valuable to make them explicit. Outcomes can be expressed in terms of actors addressed across a set of touchpoints, services provided, and content produced. They are design materials you can collect, catalogue, monitor, analyze, orchestrate, and reshape.

The elements portrayed in this section are so useful because they are universally applicable in different situations and levels. How to interpret, collect and translate them depends on the individual context and frame applied. To put them into perspective, we need to look at a design challenge from different angles, which is what the next chapter is about.

Relationships are determined by the interplay of various elements over time, coming to life as part of a larger dialogue. These elements recur across all scales and domains. Incorporating these elements explicitly as part of strategic design initiatives permits us to actively transform that dialogue, thereby transforming the relationships it embodies.

Recommendations

Consider and explore the actors critical to your business, and their journeys across various touchpoints, to set priorities for developing the enterprise

Understand and redesign the activities of the enterprise as a set of services across those touchpoints, engaging with actors in exchanges of content

Use the fractal and co-creative nature of enterprise elements as a strategic tool to transform the enterprise, in small steps but on all levels

Use these elements as the raw materials in your designs, establishing a system that makes sense to people by constituting and shaping identity, architecture, and experience

Case Study _ Vda

VDA’S ENTERPRISE

Supporting member agencies and their talent pool by facilitating the exchange between different actors of the film industry

The Verband der Agenturen (VdA) is a non-profit organization working on a national level, and regroups talent agencies all over Germany working for actors, directors, and authors. The organization understands itself as a trade association, representing its member agencies to the government, other associations and international counterparts. The sector is characterized by the collaboration of many actors and specialized professions in the context of film and theater productions.

Like any other industry, the entertainment sector is undergoing a transformation in light of digitization. Companies store profiles, pictures and videos, and other information on actors and other professionals in digital databases, communicate largely via email, and support process with information systems. Member agencies make their websites a catalogue of the clients they represent, along with content on their projects and news.

In 2007, the VdA approached the web agency °visualcosmos with a powerful idea. In their strategic planning meetings, the association’s board members had noticed that most of the content its members managed, published, and exchanged was comparatively static content, since profiles, curriculum vitae, and media changed only relatively slowly. Yet the effort to keep this content up-to-date was quite high, due to all different places and formats where it was needed. More than that, the other actors in the industry such as casting networks used the same data, resulting in a lot of replication and manual updating. The VdA wanted to expand its role beyond mere representation, and create a platform for data exchange.

The outcome of this project, the VdA Pool platform, set the standards for an automated exchange of talent profiles. It transformed the German entertainment industry, and shifted the effort of agents away from data maintenance to more valuable activities. Its design was the result of a deep dive into the Anatomy of the enterprise.

Actors

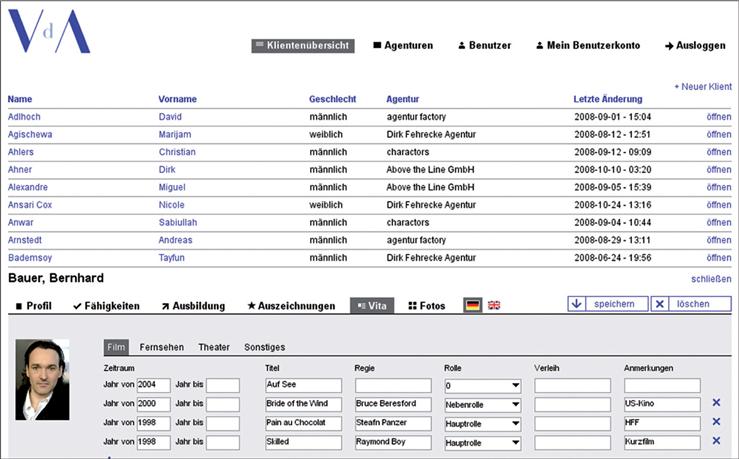

![]() Together with the client, we started investigating the stakeholder landscape, to develop an understanding of the actors the VdA needed to address with a platform for digital data exchange. A key user group would be the member agencies, who would provide the input of data into the system in collaboration with their clients, update information, and make it available to the entertainment market.

Together with the client, we started investigating the stakeholder landscape, to develop an understanding of the actors the VdA needed to address with a platform for digital data exchange. A key user group would be the member agencies, who would provide the input of data into the system in collaboration with their clients, update information, and make it available to the entertainment market.

The market actors to be addressed then included a wide range of actors with different needs. The core target group was comprised of casting agencies and production offices trying to find talents for their projects. Looking at the wider ecosystem, there were also providers of third party web portals, theaters and independent film companies, and TV channels.

The list of stakeholders was then used to create a detailed mapping of roles and relationships. In a later phase of the project, this mapping provided a basis to develop use scenarios and business cases, to inform the technical implementation of user roles, and access permissions and profiles.

Touchpoints

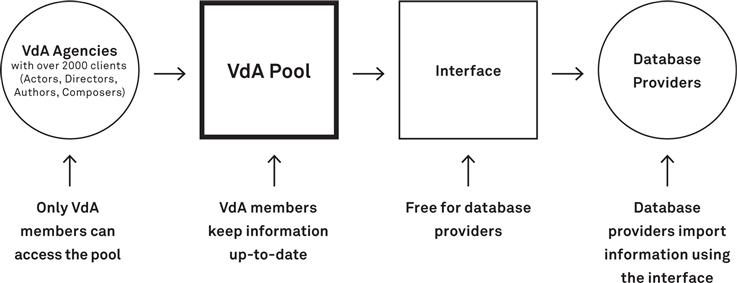

As the VdA Pool was conceived to drive all communication processes related to client profiles, there was a wide range of touchpoints to be considered. All actors should be enabled to participate in these processes according to their roles and particular needs. The choice of touchpoints to be included was largely influenced by business considerations. For example, it was a conscious decision of the members that the VdA as a non-profit organization would not make the data available publicly on the web, thereby engaging in a competitive business. Also, it was in the interest of member agencies to drive traffic to their website and sharpen their own brand identity rather than being just a data provider to a shared industry portal.![]()

This led to the decision to make the data available to market actors only in an XML format via a digital machine interface. To download data into their own database, users would have to develop their own import mechanism. The web was used to present that offering to the market, and to allow member agencies to enter and maintain their data into the VdA Pool. The VdA also provided support by phone, email, and web documentation for all actors directly accessing the pool.

Services

![]() As the VdA decided to evolve from a pure representative function to the facilitator of a data exchange process, it also had to adapt its service offerings both to member organizations and other actors in the industry. Once the target state was defined as a vision prototype of the future service, we collaboratively developed a new service model and shifted some of the existing member services.

As the VdA decided to evolve from a pure representative function to the facilitator of a data exchange process, it also had to adapt its service offerings both to member organizations and other actors in the industry. Once the target state was defined as a vision prototype of the future service, we collaboratively developed a new service model and shifted some of the existing member services.

The core services of the VdA Pool could be defined as a web interface to manually enter and update client profiles, and a machine interface to export datasets to load them into another database. In the course of the project, however, it became apparent that this scope would be extended by a machine-based service to import data into the VdA Pool, to be used by member agencies already using their own internal databases. Later, also the export mechanism was used by the association’s members to load their own data into other systems, such as databases to drive their public websites.

These new services enabled the VdA to deliver a benefit to both its members and the market they served. The organization decided to outsource service provision related to technical assets and data maintenance, and concentrate their own efforts on driving adoption of the new services.

Content

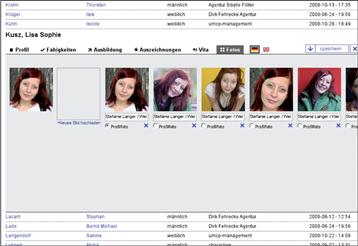

The VdA Pool initiative focused on the client profiles as the content central to the new offering, being exchanged and shared with the market. Consequently, addressing the issues of content structure, presentation and governance were a key part of the design process.![]()

The design team conducted a series of workshops with the different stakeholders to elaborate a content model that worked for all actors, aligning a large variety of formats into one standardized model, validated in the subsequent phases of the design process and also undergoing several iterations after launch. By now, this model has advanced to be the industry standard to document talent profiles, for both presentation and electronic exchange.

Together with the VdA, we elaborated a Content Strategy approach to ensure the quality, timeliness, and consistency of the pool’s content, adopting a mix of member self-service and professional governance.