Diary Studies

Introduction

Field studies (refer to Chapter 12) allow researchers to study users or customers in context and experience firsthand what the users experience; however, conducting field studies is expensive and time-consuming, and even the least privacy-sensitive individuals will rarely allow a researcher to observe them over many days or weeks. Even if you are lucky enough to conduct lengthy observations of participants, it is unlikely you can study a broad sample of your population, leaving one to wonder whether the observations are representative of the broader population.

Diary studies are one way to collect in situ, longitudinal data over a large sample. They “provide a record of an ever-changing present” (Allport, 1942) of the participant’s internal and external experiences in his or her own words. This allows you to understand the user’s experience as seen through his or her eyes, as described in his or her vernacular at the moment of occurrence. The diary can be unstructured, providing no specified format, allowing participants to describe their experience in the way they find best (or easiest). More often, though, diaries are structured, providing participants with a set of questions or probes to respond to. The beauty of diaries is that they can provide both rich qualitative and quantitative data without the need for a researcher to be present. They are ideal when you have a limited set of questions you want to ask participants, the questions are easy for participants to answer, and the experience you want to sample participants about is not so frequent that it will be disruptive for the participant to respond.

Things to Be Aware of When Conducting Diary Studies

Because participants self-report or provide the data without oversight of a researcher, you can never be sure if what you are receiving is complete, unbiased, or accurate. For example, participants are very likely to leave out embarrassing details that could be insightful for the researcher. Additionally, people are busy and will be going about their lives while participating in your diary study, so it should not be surprising that they will occasionally fail to enter useful information in their diaries. You risk disturbing the participant or altering his or her normal behavior if your diary study requires too much effort to participate. To help mitigate these effects, it is recommended that you keep your diary lightweight and instead follow up with other types of studies to probe deeper or collect insights participants may have inadvertently or consciously left out. It may be impossible to know what a participant left out or what you may have missed in any study, regardless of the method; however, if you can collect data via multiple methods, you can obtain a more holistic view and fill in gaps any single method can miss. Follow-up interviews or field studies with a selection of participants can be especially insightful. You may want to follow up on areas that seem conspicuously absent like events during certain times of the day, specific locations, and activities you know are particularly difficult.

Cartoon by Abi Jones

Diary Study Formats to Choose from

The original diary studies were done with pen and paper, but today, there are many additional options available, each with their own risks and benefits. Combining the methods ensures more variety in the data and flexibility for the participants; however, that means you must be flexible in your analysis to be able to handle multiple formats and monitor them all. Regardless of method, it is unlikely that participants will provide the level of detail in their entries that you would note if you were observing them. Making data entry as easy as possible for participants will increase the chances of good-quality data.

Paper

In paper-based diary studies, participants are provided instructions, a return-addressed, postage-paid envelope, and a packet of materials to complete during the study. Most often, the materials include a small booklet of forms to complete. In addition to completing the forms, participants may be asked to take photos throughout to visually record their experiences. With the ubiquity of digital photography, it is quite easy for participants to e-mail you their photos or upload them to your account in the cloud.

Benefits

■ No hardware or software needed so anyone can participate

■ Portable

■ Low overhead to provide photos

■ Cheap

Risks

■ The overhead of mailing back the booklet is surprisingly high, even if a return-addressed, postage-paid envelope is provided. You may end up not collecting any data from a set of participants, even if they filled out some/most of the diary.

■ Handwriting can be terribly difficult to read and interpret.

■ For most analysis methods (see below), you will need to have the diaries transcribed. That takes time and money.

■ Unless you ask participants to mail their entries back throughout the study, which requires more effort for the participants and more expense for you, you must wait for days or weeks until the study is over before you can begin any analysis. All other formats described below allow researchers to monitor data as they are entered and begin manipulating them (e.g., transcription, analysis) as soon as the study is over.

Nearly everyone has access to an e-mail account (although this may not be the case in emerging market countries), so asking participants to periodically e-mail you their entries, include links to websites they visited, and attach digital photos, videos, etc., is doable by most potential participants. You can send a reminder e-mail with your questions/probes at set times (see “Sampling Frequency”) for the participant to reply to.

Benefits

■ Nearly everyone can participate

■ No need to deal with paper and physical mail

■ Everything is typed so no need to decipher someone’s handwriting

■ No need for transcription

■ Instant submissions

Risks

■ Not all user types access their e-mail throughout the day so they may wait to reply until the end of the day, or worse, the following morning, risking memory degradation.

■ Depending on how participants take photos or videos, they may have to download them to a computer before they can attach them to e-mail, decreasing the likelihood of photos actually being included.

■ You will miss out on participants who do not use e-mail. This could mean you undersample certain age groups (e.g., older adults who prefer paper mail or younger adults who prefer texting).

Voice

Allowing participants to leave voice messages of their entries can provide much richer descriptions along with indications of their emotional state at the time of the entry, although it can be difficult to interpret emotions (e.g., what sounds like excitement to you may actually be experienced as anxiety by the participant). Some voice mail services like Google Voice will provide transcripts, but these do not work well if the background is noisy or if the participant’s dialect is difficult for the system to interpret. You can also just do voice recordings on a smartphone that can be e-mailed.

Benefits

■ Low overhead for the participant to submit

■ Richer data

Risks

■ Participants may not be able to make phone calls when they wish to submit an entry (e.g., in a meeting), so they will have to make a note of it and call later. The emotion of the moment may have passed by that time.

■ No voice mail system will be 100% accurate in its transcription. A human being will need to listen to every entry for accuracy and fill in what is missing or incorrect.

Video Diary Study

Video diaries are popular and can be an engaging method of data collection for both the participant and the researcher. A large percentage of the population can record video on their phones or tablets and many people in the US have desktops or laptops with a webcam. If you are interested in studying a segment of the population that does not have these tools available, you may choose to loan out webcams or cheap cell phones with video-recording capability. Be aware that different user types prefer different video services (e.g., YouTube, Vimeo) so choose a service that you think your users are most likely to currently use.

Benefits

■ Videos provide rich audio and visual data, making it excellent for getting stakeholders to empathize with the user.

■ It is also easier to accurately detect emotion than from voice alone.

Risks

■ Not all situations allow participants to record and submit videos at the moment (e.g., in a meeting, no Internet connection) so they may have to wait, risking memory degradation.

■ Depending on bandwidth availability, some participants may have difficulty uploading their videos or may be charged a fee if attempting to do it via their mobile network rather than Wi-Fi. Speak with participants in advance to understand their situation and ways to work around them (e.g., download videos onto a portable drive and mail it to you, provide mobile data credits).

■ Unless participants keep the instructions in front of them when creating the video entries, it is possible they may forget to answer all of the questions and include all of the information you are seeking. This format is also prone to digression so you may have additional content to sort through that is not helpful to your study.

■ Transcription will be required for certain types of data analysis (see below), which requires time and money.

SMS (Text Message)

Like voice diaries, researchers can create a phone/message account to accept text messages (SMS messages). This option can be especially appealing to younger users that prefer texting over other forms of written communication.

Benefits

■ Submissions are already transcribed.

■ Easy for participants to quietly submit entries in nearly all situations.

■ Photos can easily be sent via MMS if taken with one’s phone.

Risks

■ Depending on the participant’s mobile plan, this can cost participants money to participate (and quite a lot, if the participant has overage fees). You will need to reimburse participants, on top of the incentive.

■ Typing on a mobile phone may discourage lengthy explanations. Typos and bizarre autocorrections can make interpreting some entries difficult, although amusing!

Social Media

Some user types spend a significant portion of their day on social networks so collecting diary study entries via Facebook, Google +, Tumblr, Twilio, or Twitter (just to name a few) can be ideal for real-time data collection.

Benefits

■ You may be able to see their study entries alongside the rest of their content, providing additional context and insight to your participants.

■ It is easy to include photos, videos, and links with their submissions.

■ If participants are already on their social networks, it is less likely they will delay their diary submissions until later in the day.

Risks

■ If participants are not sharing their entries privately (e.g., via Direct Messaging on Twitter), they may constrain what they tell you even more than via other formats because of what their followers may think, so it is important that you encourage private sharing.

■ Some services limit the content that can be shared (e.g., tweets are limited to 140 characters), so you may miss out on important information.

■ It is difficult to provide a specific format for participants to respond to.

Online Diary Study Services or Mobile Apps

Several online services and mobile apps have been developed to conduct diary studies. A web search for “online diary tool” and/or “diary app” will show you the most current tools available. Features vary between tools. Some integrate with Twitter, while others allow verbal or video entries to be submitted. Most tools have web UIs to monitor data collection.

Benefits

■ Data are collected specifically for the purpose of analysis, so transcription is not needed.

■ Notifications automatically remind participants when to submit their entries. All of the other methods listed require the researcher to manually (e.g., e-mail, SMS, phone call) remind participants to submit his or her entries.

■ Participants who have smartphones can access these services or apps anytime, anyplace.

■ You may be able to capture the participant’s location at the time of his or her entry, but you need to be transparent about any data you are automatically collecting.

Risks

■ Not all user types have smartphones, so you will need to offer additional data collection methods if you want to cover a representative sample of your population.

■ Depending on your participant’s data plan, submitting entries over his or her mobile network can be costly, so you will need to reimburse participants in addition to the incentives.

Sampling Frequency

Once you have decided the format for your study, you have to decide how often you want participants to enter data. Regardless of which format you choose, you should allow participants to submit additional entries whenever they feel appropriate. Perhaps they remembered something they forgot to mention in a previous entry or there was some follow-up consequence from a previous incident that they could not have known about at the time of their last entry. Allowing additional entries can provide immense benefit in understanding the participant’s experience. If there are a minimum number of entries you are asking participants to submit per day, balance this with the length of the study.

End of Day

The quickest and lightest-weight method of data collection is to ask participants to provide feedback at the end of each day. Hopefully, they have taken notes throughout the day to refer to, but if they have not, it is likely participants will have forgotten much about what they experienced, the context, how they felt, etc. This is the least valid and reliable method.

Incident Diaries

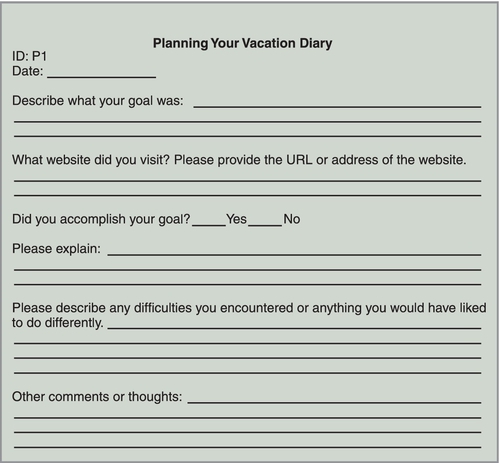

Incident diaries are given to users to keep track of issues they encounter while using a product. Participants decide when it is appropriate to enter data (i.e., neither the researcher nor the tool to submit data notifies the participant when it is time to submit an entry). Worksheets may ask users to describe a problem or issue they encountered, how they solved it (if they did), and how troublesome it was (e.g., Likert scale). The purpose of incident diaries is to understand infrequent tasks that you might not be able to see even if you observed the user all day. In the example shown (see Figure 8.1), planning a vacation often happens over an extended period and during unplanned times. You cannot possibly be there to observe on all of those occasions, and you do not want to interrupt their natural behavior:

■ They are best used when problems or tasks are relatively infrequent. It is important to remember that frequency does not equate with importance. Some very important tasks happen rarely, but you need to capture and understand them. Frequent tasks can and should be observed directly, especially since participants are usually unwilling to complete diary entries every few minutes for frequent tasks.

■ When you are not present, there is a chance that the participants will not remember (or want) to fill out the diary while they are in the middle of a problem. There is no way of knowing whether the number of entries matches the number of problems actually encountered.

■ The participant may lack the technical knowledge to accurately describe the problem.

■ User perception of the actual cause or root of the problem may not be correct.

Set Intervals

If you know the behavior you are interested in studying happens at regular intervals throughout the day, you may want to remind participants at set times of the day to enter information about that behavior. For example, if you are developing a website to help people lose weight, you will want to notify participants to submit entries about their food consumption during meal times. It is ideal if the participants can set the exact times themselves since it would be time-consuming for you to collect this information from each participant.

Random or Experiential Sampling

Experience sampling methodology (ESM) was pioneered by Reed Larson and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983). This method randomly samples participants about their experiences at that moment in time. You are not asking about what happened earlier in the day but rather what is happening right now and how the participant is experiencing it. Typically, the participant receives random notifications five to ten times per day. Because this is random, you may not “catch” the participant during an infrequent but critical moment. As a result, this sampling frequency may not be appropriate. However, if you want to learn about experiences that are more frequent or longer-lasting, this is ideal. For example, the case study in this chapter discusses Google’s Daily Information Needs ESM study. People need information throughout their day, but these needs are often so fleeting that we are not even conscious of them. An ESM study is likely to catch participants during many of those information-need moments. By drawing the participants’ attention to the need, they can describe their experiences (e.g., what triggered the need, where they are, where they are looking for the information).

Preparing to Conduct a Diary Study

If a diary study will be part of a multiphase research plan including follow-up surveys or interviews, you will need to include enough time for a pilot study and analysis of the diary study data before proceeding to the next steps. No matter how large or small your study is, a pilot is always advised.

Identify the Type of Study to Conduct

The format of your diary study should be influenced by your user type, as well as the behavior you are studying. If your users do not have smartphones, loaning them a smartphone in order to ensure easy data collection via a diary study app may backfire when participants struggle with the technology rather than focus on the behavior you are trying to study. If you have a diverse population, you may need to collect data via multiple methods, so now is the time to figure out how you will combine the data from each method into one coherent data set for analysis.

Recruiting Participants

As with any research study, you need to be transparent with participants about what will be expected of them during the study. Communicate clearly the length of the study, how often they will need to submit information, how they need to submit it, and how much effort is expected of them. If you underestimate the time or effort required, participants may feel deceived and stop participating.

There is no guideline for the recommended number of participants in a diary study. Sample sizes in HCI studies are typically between 10 and 20 participants, but in the case study in this chapter, Google recruited 1200 participants. The sample size should be based on how variable your user population is and how diverse the behavior is that you want to study. The more diverse your population and behavior, the larger your sample size should be.

Diary Materials

List your research questions and then identify the ones that are best studied longitudinally and in the users’ context. Are these questions that participants can actually answer (e.g., possess technical knowledge to describe what they experienced accurately)? Are they too personal or is there any reason a participant might not honestly or completely report? Is the phenomenon you wish to study too infrequent to capture over several days or weeks?

Identify the key questions you want to ask users in each report so you can study the same variables over time, for example (e.g., where they were at the time of the experience, how easy or difficult it was, who else was present at the time). To learn more about question design, refer to Chapter 9, Interviews and Chapter 10, Surveys. Remember that the more you ask, the less likely you will have a high compliance rate. Pilot testing is crucial to test your instructions, the tool you plan to use, the clarity of your questions, the quality of the data you are getting back, and the compliance rate of your participants.

Length and Frequency

As with field studies, you will want to know if the time you plan to study your users is indicative of their normal experience or out of the ordinary (e.g., holidays). You also need to determine how long it is likely to take for the participants in your study to experience the behavior you are interested in a few times. For example, if you are studying family vacation planning, you may need to collect diary entries over a period of weeks, rather than days. On the other hand, if you are studying a travel-related mobile app used at the airport, you may only need to collect diary entries for one day (the day of the flight). You will likely need to do some up front research to determine the right length of the study and how often to sample participants.

Fewer interruptions/notifications for entries will result in high compliance with the study because participants will not get burnt out. On the downside, because sampling is infrequent, you may miss out on good data. More interruptions may lead to a lot of data in the beginning of the study, but participants will burn out and may decrease the quality or quantity of data submitted over time. A pilot study should help you determine the right balance, but in general, five to eight notifications per day are ideal.

If you are able to collect data from a large sample of your population, you may wish to break up the data collection into waves. For example, instead of collecting data from 1000 participants during the same two-week period, you could conduct the study with 250 participants every two weeks, spread out over a two-month period. If you suspect that differences may arise during that two-month period, spreading out data collection can help you study that, assuming that participants are randomly distributed between waves and all other independent variables are constant.

Incentives

Determining the right level of incentives is tricky for longitudinal studies. Research ethics require that participants be allowed to withdraw without penalty from your study at any time. However, how do you encourage participants to keep submitting data for days or weeks? One option is to break the study into smaller pieces and provide a small incentive for every day that they submit an entry. You can provide a small bonus incentive to those that submit entries every day of the study. It should not be so large as to coerce participants into submitting incorrect entries just to earn the incentive. The actual incentive amounts can vary greatly depending on the amount of effort required and length of study (e.g., $25 to $200). If it is possible to go a whole day or several days without actually encountering the behavior you are studying (e.g., planning a vacation), then providing daily incentives is likely too frequent, so move to weekly incentives.

The amount of the incentive should be commensurate with the level of effort the study requires. Frequent, random notifications for information can be highly disruptive, so make sure the incentive is enough to be motivating. Periodic, personal e-mails thanking the participant for his or her effort can also go a long way!

Conducting a Diary Study

Train the Participants

When recruiting participants, you need to set expectations about the level of effort required for the study. You will also need to remind them in the instructions you send them when the study begins.

If you want participants to include photos in their diary entries, provide instructions about what the photos should be about. Give clear examples about what kind of photos are helpful and what kind are not. For example, “selfies” may be useful if you are studying user emotions or dieting but are unlikely to be helpful if you are studying information needs.

Monitor Data Collection

If you are conducting the study electronically, do not wait until the study is over to look at the data. Check each day for abnormalities. If this is a study where you expect participants to submit entries multiple times every day, look for participants that are not submitting any data and check in with them. Is there a problem with the tool? Have they forgotten about the study or have they changed their mind about participating? Alternatively, does the data from some participants look … wrong? For example, the entries do not make sense or the fragments they are providing are simply not enough to be useful? Contact participants to give feedback about their participation (or lack thereof). If they are doing a great job, tell them to keep up the good work!

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Depending on the number of participants, number of daily notifications, and length of your study, you may have thousands of data points to analyze. There are a few options available depending on your data, time, and skill set.

Data Cleaning

As diligent as you may have been in preparing for data analysis, instructing participants, and testing your data collection materials, you will likely have some data that should be discarded prior to analysis. This might include participants that did not follow instructions and provided inappropriate responses, those that included personally identifying information (PII), such as phone numbers, or those that dropped out early in the study. Decide in advance what your rules are for excluding data and then write R, SPSS, SAS, etc. scripts or macros in Excel to clean your data.

Affinity Diagram

An affinity diagram is one of the most frequently used methods for analyzing qualitative data. Similar findings or concepts are grouped together to identify themes or trends in the data and let you see relationships. A full discussion of affinity diagrams is presented in Chapter 12, “Focus Groups” on page 363.

Qualitative Analysis Tools

Several tools are available for purchase to help you analyze qualitative data (e.g., diaries, interviews, focus groups, field study notes). These tools can help you look for patterns or trends in your data or quantify your data, if that is your goal. Some allow you to create categories and then search for data that match those categories, whereas others are more suited for recognizing emergent themes. A few can even search multimedia files (e.g., graphics, video, audio).

Because most of these programs require that the data be in transcribed rather than audio format, they are best used only when you have complex data (e.g., unstructured interviews) and lots of it. If you have a small number of data points and/or the results are from a very structured interview, these tools would be unnecessary and likely more time-consuming. A simple spreadsheet or affinity diagram would better serve your purposes.

Prior to purchasing any tool, you should investigate each one and be familiar with its limitations. For example, many of the products make statements like “no practical limit on the number of documents you can analyze” or “virtually unlimited number of documents.” By “documents,” they mean the number of transcripts or notes the tool is able to analyze. The limits may be well outside the range of your study, but investigate to be sure. The last thing you want is to enter in reams of data only to hit the limit and be prevented from doing a meaningful analysis. In addition, a program may analyze text but not content. This means that it may group identical words but is not intelligent enough to categorize similar or related concepts. That job will be up to you.

Below is a list of a few of the more popular tools on the market today:

■ ATLAS.ti® supports qualitative analysis of large amounts of textual, graphical, audio, and video data.

■ Coding Analysis Toolkit (CAT) is the only free, open-source analysis software in our list. It supports qualitative analysis of text data.

■ The Ethnograph by Qualis Research Associates analyzes data from text-based documents.

■ HyperQualLite is available as a rental tool for storing, managing, organizing, and analyzing qualitative text data.

■ NVivo10™ by QSR is the latest incarnation of NUD*IST™ (Non-numerical Unstructured Data-Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing), a leading content analysis tool.

■ MAXQDA™ supports qualitative and quantitative analysis of textual, graphical, audio, video, and bibliographic data.

Crowd Sourcing

You may have a taxonomy in mind that you want to use for data organization or analysis. For example, if you are collecting feedback from customers about their experience using your travel app, the categories might be the features of your app (e.g., flight search, car rental, account settings). If so, you can crowd source the analysis among volunteers within your group/company or people outside your company (e.g., Amazon’s Mechanical Turk). You would ask volunteers to “tag” each data point with one of the labels from your taxonomy (e.g., “flight search,” “website reliability”). This works well if the domain is easy for the volunteer to understand and the data points can stand alone (i.e., one does not need to read an entire diary to understand what the participant is reporting).

If you do not have any taxonomy in mind, you can create one by conducting an affinity diagram on a random subset of your data. Because this is a subset, it will likely be incomplete, so allow volunteers the option to say “none of the above” and suggest their own label.

If you have the time and resources, it is best to have more than one volunteer categorize each data point so you can measure interrater reliability (IRR) or interrater agreement. IRR is the degree to which two or more observers assign the same rating or label to a behavior. In this case, it is the amount of agreement between volunteers coding the same data points. If you are analyzing nominal data (see next section), IRR between two coders is typically calculated using Cohen’s kappa and ranges from 1 to − 1, with 1 meaning perfect agreement, 0 meaning completely random agreement, and − 1 meaning perfect disagreement. Refer to Chapter 9, “Interviews” on page 254 to learn more about Cohen’s kappa. Data points with low IRR should be manually reviewed to resolve the disagreement.

Quantitative Analysis

Regardless of which method you use, if you are categorizing your data in some way, you can translate those codes into numbers for quantitative data analysis (e.g., diary entries about shopping equal “1,” work-related entries equal “2”). This type of data is considered “nominal data.” Additionally, if you included closed-ended questions in your diary, you can conduct descriptive statistics (e.g., average, minimum, maximum), measures of dispersion (e.g., frequency, standard deviation), and measures of association (e.g., comparisons, correlations). If your sample size is large enough, you can also conduct inferential statistics (e.g., t-tests, chi-square, ANOVA). A more detailed discussion of quantitative analysis can be found in the “Data Analysis and Interpretation” section in Chapter 10 on page 290.

Communicating the Findings

Because the data collected during diary studies are so rich, there are a wide variety of ways in which to present the data. For example, data may be used immediately for persona development, to develop an information architecture, or to inform product direction. There is no right or wrong answer; it all depends on the goals of your study, how your data stack up, and the method you feel best represents your data. In the end, a good report illuminates all the relevant data, provides a coherent story, and tells the stakeholders what to do next. Below, we offer some additional presentation techniques that work especially well for diary data. For a discussion of standard presentation techniques for any requirements method, refer to Chapter 15, Concluding Your Activity on page 450.

Three frequently-used methods for presenting or organizing your data are the artifact notebook, storyboards, and posters:

■ Artifact notebook. Rather than storing away the photos, videos, and websites participants shared with you, create an artifact notebook. Insert each artifact collected, along with information about what it is and the implications for design. These can be print notebooks if your materials lend themselves well to that medium (e.g., photos), but they may work better as an electronic file. Video and audio files offer such a rich experience for stakeholders to immerse themselves in, so making these easy to access is critical. These can serve as educational materials or inspiration for the product development team.

■ Storyboards. You can illustrate a particular task or a “day in the life” of the user through storyboards (using representative images to illustrate a task/scenario/story). Merge data across your users to develop a generic, representative description. The visual aspect will draw stakeholders in and demonstrate your point much faster. This is also an excellent method for communicating the emotion participants may have experienced in their submissions. Showing pure joy or extreme frustration can really drive home the experience to stakeholders.

■ Posters. Create large-scale posters and post them around the office to educate stakeholders about the most frequent issues participants reported, photos they shared, insightful quotes, personas you developed based on the data, new feature ideas, etc.

Hackos and Redish (1998) provides a table summarizing some additional methods for organizing or presenting data from a field study, but this also works well for diary studies. A modified version is reproduced here as Table 8.1.

Table 8.1

Method for organizing or presenting data (Hackos & Redish, 1998)

| Analysis method | Brief description |

| Lists of users | Examine the types and range of users identified during your study, including estimates of their percentages in the total user population and a brief description of each. |

| Lists of environments | Examine the types and range of environments identified during your study, including a brief description of each. |

| Task hierarchies | Tasks are arranged in a hierarchy to show their interrelationships, especially for tasks that are not performed in a particular sequence. |

| User/task matrix | Matrix to illustrate the relationship between each user type identified and the tasks they perform. |

| Procedural analysis | Step-by-step description examining a task, including the objects, actions, and decisions. |

| Task flowcharts | Drawings of the specifics of a task, including objects, actions, and decisions. |

| Insight sheets | List of issues identified during the field study and insights about them that may affect design decisions. |

| Artifact analysis | Functional descriptions of the artifacts collected, their use, and implications/ideas for design. |

Pulling It All Together

In this chapter, we have discussed a way of collecting longitudinal data across a large sample of your population. Diary studies provide insights about how your target population lives and/or works in their own words. This information can be used to jump-start field studies, interviews, or other methods. They can also stand alone as a rich data set to develop personas and scenarios and inspire new feature creation.

At Google, we take a somewhat different approach. We do not try to build exactly what people tell us they want, but we do respect our users’ ability to tell us generally what they need. In fact, one reason for Google’s success is that we have done an excellent job using what people tell us they want to improve search results. People tell us what they want millions of time a day by typing or speaking queries into search boxes. Teams then create new products and features that are often first tested in our usability labs and then live tested post-launch to ensure that the changes actually improve the user experience.

There is a subtle distinction between listening to our click stream and asking users what they want. In Ford’s example, people want a specific solution to a general problem. A faster horse is a specific solution to a general need for faster transportation. In many cases with Google, people can articulate general needs, but not specific ways to meet them. For example, people may know that they are hungry. They typically do not know that they want go to a “Mexican restaurant near Mountain View that has 4 + stars.” In response to a query like “restaurants,” we provide a list of potential ways to meet their need and let them choose which one works best for them. Listening to our users is not our only source of innovation, but we believe that it can be a useful one.

One consistent ingredient of innovation is the identification of needs. In fact, Engelberger (1982) asserted that only three ingredients are needed for innovation: (1) a recognized need, (2) competent people with relevant technology, and (3) financial support. Google has incredibly talented, passionate, and hardworking people. We have technology that produces relevant results. And we have more than adequate financial support. Only the recognition of needs remains.

A first step toward innovation is thus the identification of needs that people have but that they do not currently enter into Google Search. We began to take tentative steps toward identifying needs in 2011 through what would come to be called “Daily Information Needs” (DIN) studies. The DIN method is predicated on the belief, built through experience with the query stream, that people are able to articulate at least some of their needs. It posits that even if Henry Ford was right that we should not ask users to design specific solutions, people can tell us about their needs, which should inform the solutions we design.

The DIN Method

Overview

Our DIN method is a modern interpretation of a traditional diary study methodology, Csikszentmihalyi’s experience sampling method (ESM) (Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983), and Kahneman’s day reconstruction method (DRM) (Kahneman, 2011; Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004). Traditionally, ESM studies capture rich time slices of how people experience everyday life. By randomly interrupting recruited participants during the course of their days during the study, ESM hopes to capture fleeting states, such as emotions, and to avoid confounds created by retrospective reconstruction and memory of daily experiences. We used an end-of-day (EOD) survey to capture the DRM component of our study. It gives participants the opportunity to see what they reported throughout the day and then elaborate or reflect further without getting in the way of ordinary life. DIN studies are also similar to diary studies in that self-reported data are collected from the same participants over multiple days.

DIN studies are not for the disorganized or the unmotivated. They require a large amount of work up front for planning and recruitment. Researchers and other team members must keep wayward participants on task, and during analysis, they must wade through the mountains of data that are collected. While a typical usability study may require 8-12 hours of interaction with participants over a couple days, DIN studies require consistent monitoring of participants over days, weeks, and even months. Literally dozens of people worked on each DIN study. Team members included internal recruiters, external recruiting vendors, product team members, software engineers, designers, and researchers. They helped at different times and in different ways, but we had at least one researcher coordinating activities full-time during the entire course of each study, which have lasted from several weeks to several months depending on the number of participants in the study. Without such a large and dedicated team, DIN studies would not be possible, at least not at Google scale.

We ran our first, much less ambitious DIN pilot study in 2011. Our goal was to capture information needs of real users that may not be reflected in query logs. We sought to minimize intrusiveness and maximize naturalism, which is what led us to our composite DIN methodology. We started with 110 participants in a three-day study. Each year, we have expanded the number of participants recruited and length of the study, so that our 2013 study (described below) involved data collected from 1000 + compensated participants across five contiguous days. We collected the data in waves over multiple months. Each year, we have improved the quality of the study, and we have expanded to some countries outside the US as well.

Participants

In a perfect world, participants would be a random sample from the population to which we planned to generalize results. In our case, this would have been a random sample of international web users. Due to multiple pragmatic, logistic, and technological constraints, we most often used a representative sample of US Internet users based upon age, gender, location, and other demographic/psychographic characteristics. To increase representativeness, some participants were recruited by Google recruiters, and some were recruited by an external recruiting agency. Participants were motivated to participate by a tiered compensation system that was tied to the number of daily pings to which they responded and the number of EOD survey responses they completed. Each person participated for five consecutive days. The start dates of participant cohorts were staggered so that needs were collected for each day of the week for approximately three months.

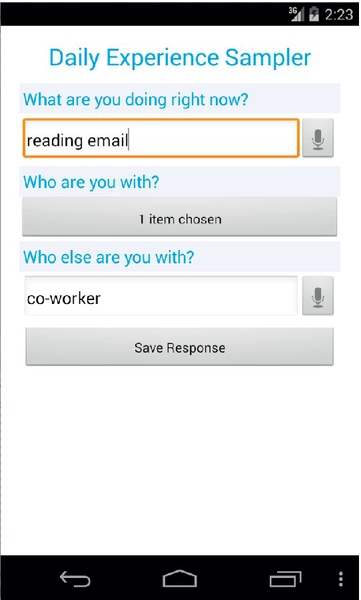

Tools

We used an open-source tool developed by Google engineer Bob Evans called the Personal Analytics Companion (PACO) app to collect data. This is a free tool anyone can download from Google Play and Apple iStore (see Figure 8.2). Working closely with Bob allowed us to customize the tool and data collected to meet our unique needs. Participants installed PACO (www.pacoapp.com) on their Android device and then joined the appropriate study. At the time of the study, the app was available only on Android devices.

We also created websites to support the needs of both Google research assistants and study participants. These sites included text instructions, video instructions, FAQs, and clear paths of escalation for issues that were not sufficiently addressed by site content. It took a lot of time and effort to develop the materials, but it was time well spent. The sites answered scheduling, study setup, and incentive-related questions and, in so doing, freed researchers to focus on more important tasks.

Procedure

DIN pings: Capturing the Experiencing Self

Participants were pinged by PACO at eight random times during normal waking hours during the five days of the study. Participants responded to pings by answering four simple questions on their mobile device: (1) What did you want to know recently? (2) How important was it that you find this information? (3) How urgently did you need the information? and (4) What is the first thing that you did to find this information? These questions were pretested to generate high-quality data and were designed to allow completion in about a minute. This was done via pilot testing and getting feedback from participants about the questions, what they were able to articulate about their experiences, what was difficult to answer, and which questions received the clearest, most useful data. In case participants missed pings, they were instructed to enter DIN as they occurred throughout the day. Participants could respond to pings by text or voice entry and could include pictures of their information need as well. Figures 8.3–8.5 show representative photos of actual needs submitted. (To protect participant privacy, these are not the actual photos submitted but replicas.)

EOD Survey Pings: Capturing the Remembering Self

At the end of each study day, PACO messaged and e-mailed participants reminders to complete the EODs. We recommended that participants completed the survey using a desktop or laptop computer because of the difficulty to view the form and respond with complete answers on a mobile device. The EOD survey included all of the DIN information that participants submitted during the day and asked them to elaborate on each need. Selected questions included the following:

1. Why did you need the information?

2. How did you look for the information?

3. How successful were you in finding the information?

4. Where were you when you needed the information?

5. What devices did you use to find the information?

Some of these questions were forced-choice, and some were free text.

Limitations

No study is perfect, and despite the assiduous work of our entire team, DIN is no exception. Some of the issues below are likely to be addressed in subsequent DIN studies, while others are inherent to the method itself. Different balances could be struck, but some limitations can never be completely eliminated.

Technological Limitations

One limitation of our early DIN studies is that PACO was available only for the Android operating system. We therefore were unable to collect needs from iOS users and cannot be sure that our data reflect the needs of all users. An iOS version of PACO is now available, and future DIN studies will address this limitation.

Incentive Structure

We created an incentive structure that we felt would provide an optimal balance between data quality and data quantity. We sought to motivate participants that had valid information needs to report the needs when they otherwise may not have, but we did not want to create so much motivation that participants would make up fake needs just so that they could earn the maximum incentive. After some trial and error, we settled on a tiered structure that provided incentives for initial study setup, response to a minimum number of pings, and submission of a minimum number of EOD surveys. Inspection of our data suggests that the tiered structure worked well for us, but we encourage to you to think carefully about what you want to maximize and to experiment with different structures. In the end, this limitation cannot be eliminated, but we feel that it can be managed.

Findings

We discovered several interesting findings in 2013. One area we examined was around the value of photos in ESM studies (Yue et al., 2014). Women and participants over 40 were significantly more likely to submit photos than others. Although many of the photos participants provided did not aid our analysis (e.g., selfies, photos that did not include information beyond what was in the text), we did find that text submissions that included photos were of better quality than those without photos. We compared the submissions of those that submitted photos versus those that did not and also looked within the submissions of those that submitted any photos. In both cases, responses that included photos included richer text descriptions.

The data collected in our annual study are a source of innovation for product teams across all of Google, not just within Search. For example, in Google Now (Google’s mobile personal assistant application), DIN data led to 17 new notification cards and two voice actions, identified eight user-driven contexts, and improved 22 existing cards. Roles across the company including UX, engineering, product management, consumer support, and market research ask for the DIN data and use it to inform their work.

Lessons Learned

Pilot Studies

Although running a pilot study feels like a distraction from important preparation for the “real” study and takes serious time when you may be under pressure to begin collecting data, we strongly encourage you to run at least one. Pilots with team members and colleagues revealed typos, unclear instructions, technical installation issues with specific phone models, time zone logging issues, extraneous and missing pings, and other assorted issues. In addition, pilots with external participants were invaluable in refining the method and the creation of complete, accurate FAQs. Pilots saved time for us, when it really mattered with real participants.

Unfortunately, we did not do an analysis of the pilot data we collected and so we did not catch issues with data collection in a couple of the questions. This was caught during the data cleaning stage of our final analysis, but if it had been caught during the pilot, significant time and effort could have been saved in the cleaning phase.

Analysis

Preparation for DIN studies takes weeks. Running the studies takes days. Processing and analyzing the data takes months. This is due to the sheer volume of the data, the complexity of the data, and the numerous ways it can be coded and analyzed. There is seldom a “right” way to analyze qualitative data, but there are ways that are more and less useful, depending on your needs. Over the course of a literature review, several affinity diagramming exercises, and substantial hand coding, we developed a coding scheme that works for us, but it took time. Expect coding and analysis to take longer than planning and running the study combined.

Conclusion

Henry Ford and Steve Jobs’ famous quotes are often used to justify the exclusion of users from the innovation process. We disagree and believe that users and user research can play a critical role. While it is clear that user wants and needs do not provide step-by-step instructions for innovation, user needs can provide important clues and data points that teams may not be able to get in any other way. For those of us for whom the understanding of needs and their solutions is less intuitive than for Ford and Jobs, DIN-like studies can be an important part of a data-driven innovation process. We hope that our experience encourages you to both adapt it to your needs and to avoid some of the mistakes we made while developing it.