Eurocurrency Markets and the LIBOR

Abstract

The international deposit and loan market in a nondomestic currency is called the Eurocurrency market, and banks that accept these deposits and make loans are often called Eurobanks. This chapter describes the major points and issues of the Eurocurrency market, providing some pertinent history as well. The reasons for and benefits of offshore banking are discussed. LIBOR, the London Interbank Offered Rate, is covered in detail, because of its use in determining variable interest rates and cost of swaps around the world. Much attention is paid in the chapter to interest rate spreads and risk, with practical examples provided. Also discussed in detail are international banking facilities and offshore banking practices, including syndicates of Eurobanks.

Keywords

Bank syndicates; Eurobanks; Eurocurrency market; Eurodollar market; IBF; international banking; international capital flow; LIBOR; LIBOR rigging; offshore banking

The foreign exchange market is a market in which monies are traded. Money serves as a means of paying for goods and services, and the foreign exchange market exists to facilitate international payments. Just as there is a need for international money payments, there also is a need for international credit or deposits and loans denominated in different currencies. The international deposit and loan market is often called the Eurocurrency market, and banks that accept these deposits and make loans are often called Eurobanks.

The use of the prefix Euro, as in Eurocurrency or Eurobank, is misleading, since the activity described is related to offshore banking (providing foreign currency borrowing and lending services) in general and is in no way limited to Europe. For instance, the Eurodollar market originally referred to dollar banking outside the United States. But now a type of Eurodollar banking also occurs in the United States. The Euroyen market involves yen-denominated bank deposits and loans outside Japan. Similarly there are Euroeuros (the name for euro-denominated bank deposits) and Eurosterling (the name for the UK pound denominated bank deposits).

The distinguishing feature of the Eurocurrency market is that the currency used in the banking transaction generally differs from the domestic currency of the country in which the bank is located. However, this is not strictly the case, as some international banking activity in domestic currency may exist. Where such international banking occurs, it is segregated from other domestic currency banking activities in regard to regulations applied to such transactions. As we learn in the next section, offshore banking activities have grown rapidly because of a lack of regulation, which allows greater efficiency in providing banking services.

Reasons for Offshore Banking

The Eurodollar market began in the late 1950s. Why and how the market originated have been subjects of debate, but there is agreement upon certain elements. Given the reserve currency status of the dollar, it was only reasonable that the first external money market to develop would be for dollars. Some argue that the Communist countries were the source of early dollar balances held in Europe, since these countries needed dollars from time to time but did not want to hold these dollars in US banks for fear of reprisal should hostilities flare up. Thus the dollar deposits in UK and French banks owned by the Communists would represent the first Eurodollar deposits.

Aside from political considerations, the Eurobanks developed as a result of profit considerations. Since costly regulations are imposed on US banks, banks located outside the United States could offer higher interest rates on deposits and lower interest rates on loans than their US competitors. For instance, US banks are forced to hold a fraction of their deposits in the form of noninterest-bearing reserves. Because Eurobanks are essentially unregulated and hold much smaller reserves than their US counterparts, they can offer narrower spreads on dollars. The spread is the difference between the deposit and loan interest rate. Besides lower reserve requirements, Eurobanks also benefit from having no government-mandated interest rate controls, no deposit insurance, no government-mandated credit allocations, no restrictions on entry of new banks (thus encouraging greater competition and efficiency), and low taxes. This does not mean that the countries hosting the Eurobanks do not use such regulations. What we observe in these countries are two sets of banking rules: various regulations and restrictions apply to banking in the domestic currency, whereas offshore banking activities in foreign currencies go largely unregulated.

Fig. 5.1 portrays the standard relationship between the US domestic loan and deposit rates and the Euroloan and Eurodeposit rates. The figure shows that US spreads exceed Eurobank spreads. Eurobanks are able to offer a lower rate on dollar loans and a higher rate on dollar deposits than their US competitors. Without these differences the Eurodollar market would likely not exist, since Eurodollar transactions, lacking deposit insurance and government supervision, are considered to be riskier than are domestic dollar transactions in the United States. This means that with respect to the supply of deposits to Eurobanks, the US deposit rate provides an interest rate floor for the Eurodeposit rate, since the supply of deposits to Eurobanks is perfectly elastic at the US deposit rate (this means that if the Eurodeposit rate fell below this rate, Eurobanks would have no dollar deposits). With respect to the demand for loans from Eurobanks, US loan rates provide a ceiling for Euroloan rates because the demand for dollar loans from Eurobanks is perfectly elastic at the US loan rate (any Eurobank charging more than this would find the demand for its loans falling to zero).

Interest Rate Spreads and Risk

Interest rates on a particular currency might be constrained by capital controls. Controls on international capital flows could include quotas on foreign lending and deposits or taxes on international capital flows. For instance, if Switzerland limits inflows of foreign money, then we could have a situation where the domestic Swiss deposit interest rate exceeds the external rate on Swiss franc deposits in other nations. Although foreigners would prefer to have their Swiss franc deposits in Swiss banks in order to earn the higher interest, the legal restrictions on capital flows might prohibit such a response.

It is also possible that a perceived threat to private property rights could lead to seemingly perverse interest rate relations. If the United States threatens to confiscate foreign deposits, the funds would tend to leave the United States and shift to the external dollar market. This could result in the Eurodollar deposit rate falling below the US deposit rate.

In general risk contributes to the domestic spread exceeding the external spread. In domestic markets government agencies help ensure the sound performance of domestic financial institutions, whereas the Eurocurrency markets are largely unregulated, with no central bank ready to come to the rescue. There is an additional risk in international transactions in that investment funds are subject to control by the country of currency denomination (when it is time for repayment) as well as the country of the deposit bank. For instance, suppose a US firm has a US dollar bank deposit in Hong Kong. When the firm wants to withdraw those dollars—say, to pay a debt in Taiwan—not only is the transaction subject to control in Hong Kong (the government may not let foreign exchange leave the country freely), but the United States may control outflows of dollars from the United States, so that the Hong Kong bank may have difficulty paying back the dollars. It should be recognized that even though domestic and external deposit and loan rates differ, primarily because of risk, all interest rates tend to move together. When the domestic dollar interest rate is rising, the external rate will also tend to rise.

The growth of the Eurodollar market is the result of the narrower spreads offered by Eurobanks. We have seen the size of the Eurodollar market grow as the total demand for dollar-denominated credit has increased and as dollar banking has moved from the United States to the external market. The shift of dollar intermediation has occurred as the Eurodollar spread has narrowed relative to the domestic spread or as individual responsiveness to the spread differential has changed.

Over time important external markets have developed for the other major international currencies (euro, pound, yen, Canadian dollar, and Swiss franc). But the value of activity in Eurodollars (which refers to offshore banking in US dollars) dwarfs the rest. In the end of 2015, the Bank for International Settlements estimated the currency composition of the Eurocurrency market to be: US dollar, 58%; euro, 26%; yen, 3%; British pound, 6%; with other currencies taking the remainder.

Fig. 5.2 illustrates the foreign assets held by banks of different nations. The major role of the United Kingdom and the United States in international banking is obvious. Note that the figure distinguishes between bank assets, including interbank claims and credit extended to nonbanks. Interbank claims are deposits held in banks in other countries. If we want to know the actual amount of credit extended to nonbank borrowers, we must remove the interbank activity. Fig. 5.2 illustrates the huge size of the interbank market in international finance. An example of interbank deposits versus credit extended to nonbanks is provided later in this chapter.

International Banking Facilities

In December 1981 the Federal Reserve permitted US banks to engage in Eurobanking activity on US soil. Prior to this time, US banks engaged in international banking by processing loans and deposits through their offshore branches. Many “shell” bank branches in places like the Cayman Islands or the Bahamas really amounted to nothing more than a small office and a telephone. Yet by using these locations for booking loans and deposits, US banks could avoid the reserve requirements and interest rate regulations that applied to normal US banking.

In December 1981 international banking facilities, or IBFs, were legalized in the US. IBFs did not involve any new physical presence in US bank offices. Instead they simply required a different set of books for an existing bank office to record the deposits and loans permitted under the IBF proposal. IBFs are allowed to receive deposits from, and make loans to, nonresidents of the United States or other IBFs. These loans and deposits are kept separate from the rest of the bank’s business because IBFs are not subject to reserve requirements, interest rate regulations, or Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation deposit insurance premiums applicable to normal US banking.

The goal of the IBF plan is to allow banking offices in the United States to compete with offshore banks without having to use an offshore banking office. The location of IBFs reflects the location of banking activity in general. It is not surprising that New York State, as the financial center of the country, has over 75% of IBF deposits. Aside from New York, California and Illinois are the only states with a significant IBF business. After IBFs were permitted, several states encouraged their formation by granting low or no taxes on IBF business. The volume of IBF business that resulted mirrored the preexisting volume of international banking activity, with New York dominating the level of activity found in other states.

Since IBFs grew very rapidly following their creation, we may ask where the growth came from. Rather than new business that was stimulated by the existence of IBFs, it appears that much of the growth was a result of shifting business from Caribbean shell branches to IBFs. After the first month of IBF operation, $29.1 billion in claims on foreign residents existed. During this same period, the claims existing at Caribbean branches of US banks fell $23.3 billion. Since this time IBF growth has continued with growth of Eurodollar banking in general. As of June 2011 the IBFs surpassed the $700 billion mark, almost entirely as interbank claims.

Offshore Banking Practices

The Eurocurrency market handles a tremendous volume of funds. Because of the importance of interbank transactions, the gross measure overstates the actual amount of activity regarding total intermediation of funds between nonbank savers and nonbank borrowers, as Fig. 5.2 shows. To measure the amount of credit actually extended through the Eurobanks, we use the net size of the market—subtracting interbank activity from total deposits or total loans existing. To understand the difference between the gross and net volume of Eurodollar activity, consider the following example.

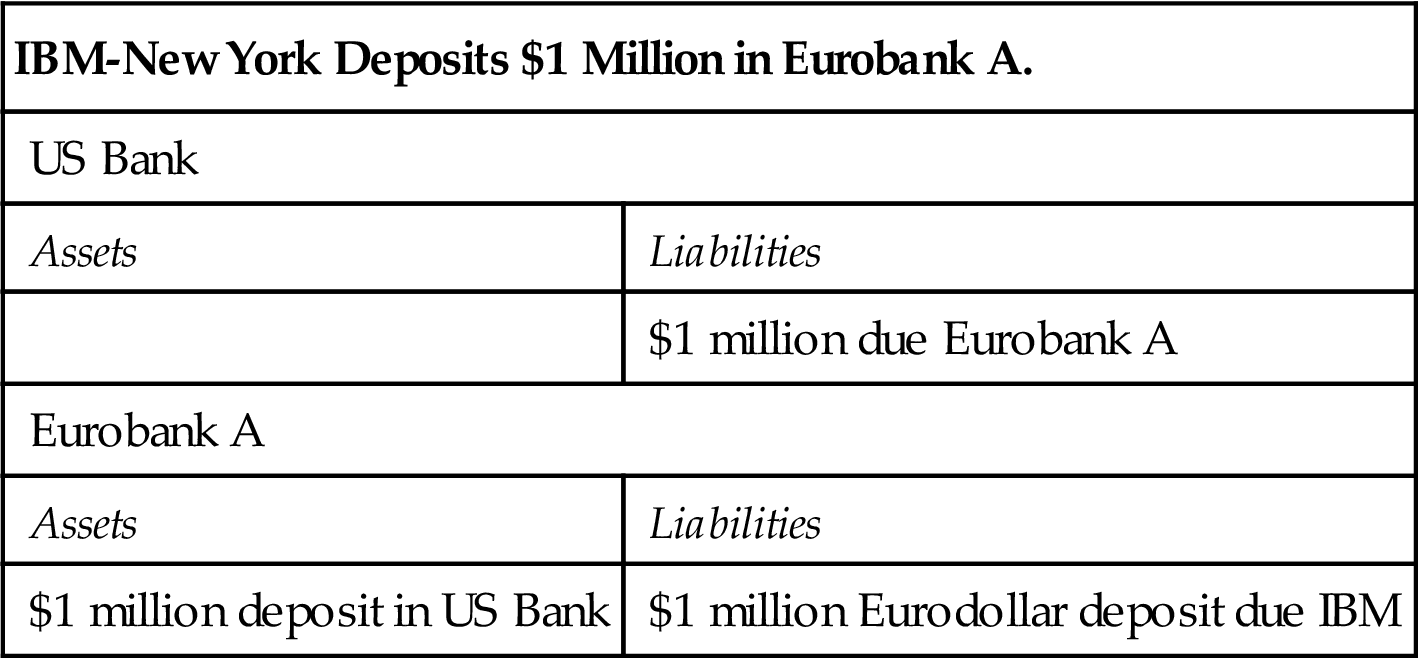

Suppose that a US firm, IBM in New York, shifts $1 million from its US bank to a Eurobank, Eurobank A, to receive a higher return on its deposits. Table 5.1 shows the T-accounts recording this transaction. The US bank now has a liability (recorded on the right-hand side of its balance sheet) of $1 million owed to Eurobank A, since the ownership of the $1 million deposit has shifted from IBM to Eurobank A. Eurobank A records the transaction as a $1 million asset in the form of a deposit it owns in the US bank, plus a $1 million liability from the deposit it has accepted from IBM. Now suppose that Eurobank A does not have a borrower waiting for $1 million (US), but another Eurobank, Eurobank B, does have a borrower. Eurobank A will deposit the $1 million with Eurobank B, earning a fraction of a percent more than it must pay IBM for the $1 million.

Table 5.1

| IBM-New York Deposits $1 Million in Eurobank A. | |

| US Bank | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million due Eurobank A | |

| Eurobank A | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million deposit in US Bank | $1 million Eurodollar deposit due IBM |

Table 5.2 shows that after Eurobank A deposits in Eurobank B, the US bank now owes the US dollar deposit to Eurobank B, which is shown as an asset of Eurobank B, matched by the deposit liability of $1 million from Eurobank B to Eurobank A.

Table 5.2

| Eurobank A Deposits $1 Million in Eurobank B. | |

| US Bank | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million due Eurobank B | |

| Eurobank A | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million Eurodollar deposit in Eurobank B | $1 million Eurodollar deposit due IBM |

| Eurobank B | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million deposit in US Bank | $1 million Eurodollar deposit due Eurobank A |

Finally in Table 5.3, Eurobank B makes a loan to BMW in Munich. Now the US bank has transferred the ownership of its deposit liability to BMW (Whenever dollars are actually spent following a Eurodollar transaction, the actual dollars must come from the United States—only the United States creates US dollars; the Eurodollar banks simply act as intermediaries.). The gross size of the market is measured as total deposits in Eurobanks, or $2 million ($1 million in Eurobank A and $1 million in Eurobank B). The net size of the market is found by subtracting interbank deposits, and thus is a measure of the actual credit extended to nonbank users of dollars. In the example, Eurobank A deposited $1 million in Eurobank B. If we subtract this interbank deposit of $1 million from the total Eurobank deposits of $2 million, we find the net size of the market to be $1 million. This $1 million is the value of credit actually intermediated to nonbank borrowers.

Table 5.3

| Eurobank B Loans $1 Million to BMW. | |

| US Bank | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million due BMW | |

| Eurobank A | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million Eurodollar deposit in Eurobank B | $1 million Eurodollar deposit due IBM |

| Eurobank B | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million loan to BMW | $1 million Eurodollar deposit due Eurobank A |

| BMW-Munich | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| $1 million deposit in US Bank | $1 million loan owed to Eurobank B |

Since the Eurodollar market deals with such large magnitudes, it is understandable that economists and politicians are concerned about the effects the Eurodollar market can have on domestic markets. In the United States, Eurodollar deposits are counted in the M3 definition of the money supply. Measures of the US money supply are used by economists to evaluate the resources available to the public for spending. Eurodollars are not spendable money but, instead, are money substitutes like time deposits in a domestic bank. Because Eurodollars do not serve as a means of payment, Eurobanks are not able to create money as banks can in a domestic setting. Eurobanks are essentially intermediaries; they accept deposits and then loan these deposits.

Even though Eurodollars do not provide a means of payment, they still may have implications for domestic monetary practice. For countries without efficient money markets, access to the very efficient and competitive Eurodollar market may reduce the demand for domestic money, because the domestic company need not use domestic currency for its transactions anymore.

All banks are interested in maximizing the spread between their deposit and loan interest rates. In this regard, Eurobanks are no different from domestic banks. All banks are also concerned with managing risk, the risk associated with their assets and liabilities. Like all intermediaries, Eurobanks tend to borrow short term and lend long term. Thus if the deposit liabilities were reduced greatly, we would see deposit interest rates rise very rapidly in the short run. The advantage of matching the term structures of deposits and loans is that deposits and loans are maturing at the same time, so that the bank is better able to respond to a change in demand for deposits or loans.

Deposits in the Eurocurrency market are for fixed terms, ranging from days to years, although most are for less than 6 months. Certificates of deposit are considered to be the closest domestic counterpart to a Eurocurrency deposit. Loans in the Eurocurrency market can range up to 10 or more years. The interest rate on a Eurocurrency loan is usually stated as some spread over LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) and is adjusted at fixed intervals, like every 3 months. These adjustable interest rates serve to minimize the interest rate risk to the bank.

Large loans are generally made by syndicates of Eurobanks. Syndicates of banks are an organized group of banks. The syndicate will be headed by a lead or managing bank; other banks wishing to participate in the loan will join the syndicate and help fund the loan. By allowing banks to reduce their level of participation in any loan, syndicates can participate in more loans. Thus each individual bank reduces their risk by having a diversified loan portfolio.

LIBOR

As of the end of 2010 the NYSE market capitalization was slightly over $13 trillion dollars, and we hear news every day of what happened to the stock market. The LIBOR affects financial assets worth at least 25 times more, but rarely receives any press. LIBOR stands for London Interbank Offered Rate and is the interest rate at which a group of large London banks could borrow from each other each morning. Loans of $10 trillion and Swaps worth about $350 trillion around the world are directly tied to the LIBOR, according to the British Bankers Association. For example, approximately half of the United States adjustable mortgages are estimated to be tied to the LIBOR.

The BBA LIBOR

In February 2014 the LIBOR changed from the BBA LIBOR to the ICE LIBOR. To understand the reasons for this we are first going to discuss the way the LIBOR was traditionally computed and then compare it to today’s methodology. The BBA LIBOR was collected by the British Bankers’ Association (BBA). The LIBOR established a value each day at 11:00 a.m. London time for each major currency. LIBOR is the key rate for fixing interest rates around the world. For instance a variable interest rate loan in some currency may be priced at 2% points above LIBOR and adjusted annually. Once a year the interest rate on the loan would be adjusted to the currency value of LIBOR plus 2% points.

LIBOR was fixed daily for the following 10 currencies: the British pound (GBP), Canadian dollar (CAD), Danish krone (DKK), euro (EUR), US dollar (USD), Australian dollar (AUD), Japanese yen (JPY), New Zealand dollar (NZD), Swedish krona (SKR), and Swiss franc (CHF). There were 15 maturities for which LIBOR was set each day, from an overnight rate all the way up to 12 months. Thus a total of 150 rates were set each day.

The daily value of LIBOR was drawn from a panel of contributing banks chosen based upon their reputation, level of activity in the London market, and perceived expertise in the currency concerned. For example, for the US dollar 16 different respected banks submitted quotes, and the four highest and four lowest quotes were eliminated. The borrowing costs for the remaining eight banks were averaged into the LIBOR rate. Shortly before 11:00 a.m. each business day, each bank reported the rate at which it could borrow funds of a reasonable market size by accepting interbank offers from banks other than the LIBOR panel of contributing banks.

Recently an investigation has begun into a possible collusion between banks to set the LIBOR. It has been alleged that there have been significant departures from the actual costs of borrowing by a number of banks. The potential misreporting can pay off greatly for banks. According to Snider and Youle (2010) a collusion among the banks to change the LIBOR by 0.25% could earn a single bank as much as $3.37 billion in a single quarter. Thus the incentive to quote incorrect rates or to collude exists.

LIBOR Rigging

Traders at many influential banks were accused of rigging the LIBOR rate, during 2006–2010. A large number of banks that have been accused of receiving excess profits from LIBOR rigging have agreed to pay large fines. Table 5.4 shows that banks have already agreed to pay almost $9 billion in fines related to LIBOR rigging, as of July, 2016.

Table 5.4

Fines Paid by Banks for LIBOR Cheating

| Bank | Date | Amount (in millions of US dollars) |

| UBS | May 20, 2015 | $203 |

| Deutsche Bank | April 23, 2015 | $2,500 |

| Lloyds TSB Bank | July 28, 2014 | $380 |

| Citigroup | December 04, 2013 | $95 |

| Deutsche Bank | December 04, 2013 | $984 |

| JP Morgan | December 04, 2013 | $108 |

| Royal Bank of Scotland | December 04, 2013 | $530 |

| Societe Generale | December 04, 2013 | $600 |

| Rabo Bank | October 29, 2013 | $1,066 |

| JP Morgan | October 21, 2013 | $92 |

| ICAP | September 25, 2013 | $87 |

| Royal Bank of Scotland | February 06, 2013 | $612 |

| UBS | December 19, 2012 | $1,500 |

| Barclays Bank | June 27, 2012 | $450 |

Source: Nytimes.com, March 23, 2016; ft.com, December 04, 2013.

In addition to fining banks, prosecutors have also charged individual traders with rigging the LIBOR. One such trader at UBS and Citigroup, Tom Hayes, was accused of setting up a network of brokers and traders to rig the LIBOR rate to create huge profit for the banks. On August 3, 2015 Tom Hayes was convicted of conspiring to rig the LIBOR rate, and sentenced to 14 years in jail later reduced to 11 years and a $1.2 million fine. In November, 2015 two Rabobank traders were convicted of LIBOR rigging, followed by three Barclays traders that were convicted in July, 2016.1 Many other people have been also charged and are awaiting trials or have pleaded guilty already.

With such massive cheating the LIBOR rate needed to be overhauled. In February 2014 the new ICE LIBOR was introduced that remedied certain weakness of the BBA LIBOR.

The ICE LIBOR

The LIBOR was published by the British Bankers Association from January, 1986 until January, 2014. In February, 2014 the LIBOR continued to be published by an organization called the ICE Benchmark Administration. This organization has refined the process of submitting quotes and reduced the number of currencies and maturities. The reduction in currencies and maturities happened, because some maturities were thinly traded and some currencies less popular resulting in more volatility in the LIBOR and more of a temptation to fix rates. Therefore LIBOR is currently limited to five currencies: USD, GBP, EUR, JPY, and CHF, with seven maturities from overnight to 12 months.

In addition to removing thin maturities, the new LIBOR has a much stronger oversight over the rates that are submitted by banks. The structure of the ICE LIBOR has independent directors overseeing the survey with participation from the Federal Reserve System, Swiss National Bank and Bank of England. The new LIBOR focuses on accountability of the banks. The senior manager from the bank that submits rate has to be able to provide evidence to support the rate submitted, and the manager is held personally liable. In this way a manager can be prosecuted for entering a false rate. In addition, analysts have been hired to examine statistical evidence to detect if any discrepancy in the submissions can be found.

The ICE LIBOR is published on a daily basis, except for certain holidays. Table 5.5 shows the rates on July 7, 2016 for all currencies and maturities. For all currencies the longer maturities have higher rates. Across currencies rates are grouped in two groups. The dollar and pound are very similar with positive rates. The other three currencies have negative rates, with the Swiss franc being strongly negative, the euro substantially negative and the yen slightly negative.

Table 5.5

LIBOR rates as of July 7, 2016

| Maturity | Currencies | ||||

| US Dollar | Pound Sterling | Swiss Franc | Japanese Yen | Euro | |

| Spot Next/Overnight | 0.4127 | 0.4787 | −0.7988 | −0.0677 | −0.4013 |

| 1 Week | 0.4378 | 0.4862 | −0.8258 | −0.0703 | −0.3871 |

| 1 Month | 0.4743 | 0.4772 | −0.8166 | −0.0529 | −0.3617 |

| 2 Month | 0.5552 | 0.4915 | −0.7916 | −0.0309 | −0.3289 |

| 3 Month | 0.6646 | 0.5187 | −0.7802 | −0.0285 | −0.3037 |

| 6 Month | 0.9349 | 0.6106 | −0.7066 | −0.0254 | −0.1917 |

| 1 Year | 1.2465 | 0.8449 | −0.5910 | 0.0625 | −0.0693 |

Summary

1. The Eurocurrency market is the offshore banking market where commercial banks accept deposits and extend loans in a currency other than the domestic currency.

2. The Eurodollar, the US dollar-denominated deposits and loans outside the US, has the highest value of activity among other currency offshore banking.

3. Compared to domestic banks, the Eurobanks have lower operating costs and are less regulated. Therefore they are able to offer narrower spread than domestic banks.

4. Because of fewer regulations, the Eurobanking has gained more popularity among investors and grown rapidly.

5. The Eurocurrency market improves efficiency of international finances. Efficiency comes from access to low-cost borrowing, lack of government regulations, and strong competition among the Eurobanks.

6. LIBOR is an important interest rate that the Eurodollar market uses as a benchmark interest rate to set its loan rates.

7. The LIBOR is collected by the ICE Benchmark Administration since February 2014.

8. International banking facilities (IBFs) are departments of US banks that are permitted to engage in Eurocurrency banking.

9. The net size of the Eurodollar market measures the amount of credit actually extended to nonbanks.

Exercises

1. Why must Eurobanks operate with narrower spreads than domestic banks? What would happen if the spreads were equal in both markets?

2. Use T-accounts to explain the difference between the gross and net size of the Eurodollar market.

3. Create an example of $10 million being deposited in the Eurodollar market by a US manufacturing firm, Motorola. Your example should include at least one interbank transaction before the dollars are borrowed by a French public utility firm, Paris Electric. How is the gross size of the Eurodollar market affected by your example? What about the net size?

4. Discuss how the Eurobanks can survive when they operate with such a small spread.

5. What could be the risks for depositors if they decide to use the Eurocurrency market for their deposits?

6. What are the IBFs? Why did the Federal Reserve authorize the establishment of the IBFs? Explain.