Forward-Looking Market Instruments

Abstract

Foreign currency liabilities of firms are due in the future, resulting in a currency exchange risk. This chapter describes hedging instruments that limit or remove the currency risk. Forward markets, futures markets, and options markets are defined and compared. An example of each type of basic hedging instrument is provided to make it easier for students to understand the similarities and differences for each instrument. In addition, a detailed discussion of different swaps markets is included in the chapter.

Keywords

Forward markets; forward premium; forward discount; currency futures; foreign exchange swap; currency swap; credit default swap; futures market; options market; call options; put options; “in the money”; recent practices

In Chapter 1, The Foreign Exchange Market, we considered the problem of a US importer buying Swiss watches. Since the exporter requires payment in Swiss francs, the transaction requires an exchange of US dollars for francs. In the discussion in Chapter 1, The Foreign Exchange Market, it was assumed that the payment was done immediately, thus the chapter discussed the spot market—exchanging dollars for francs today at the current spot exchange rate. In the real world payments are not immediate. Instead the purchaser is usually granted 30, 60, or 90 days to pay for the purchase. Thus, the transaction requires the purchaser and the seller to try to predict the future foreign currency value. This chapter deals with instruments that help cover the risk of a foreign currency value becoming too high when the importer has a foreign currency liability, or too low when the exporter has a foreign currency receivable.

Suppose we return to the example of the US watch importer. Earlier, the importer purchased francs in the spot market to settle a contract payable now. Yet much international trade is contracted in advance of delivery and payment. It would not be unusual for the importer to place an order for Swiss watches for delivery at a future date. For instance, suppose the order calls for delivery of the goods and payment of the invoice in 3 months. Specifically, let’s say that the order is for CHF100,000.

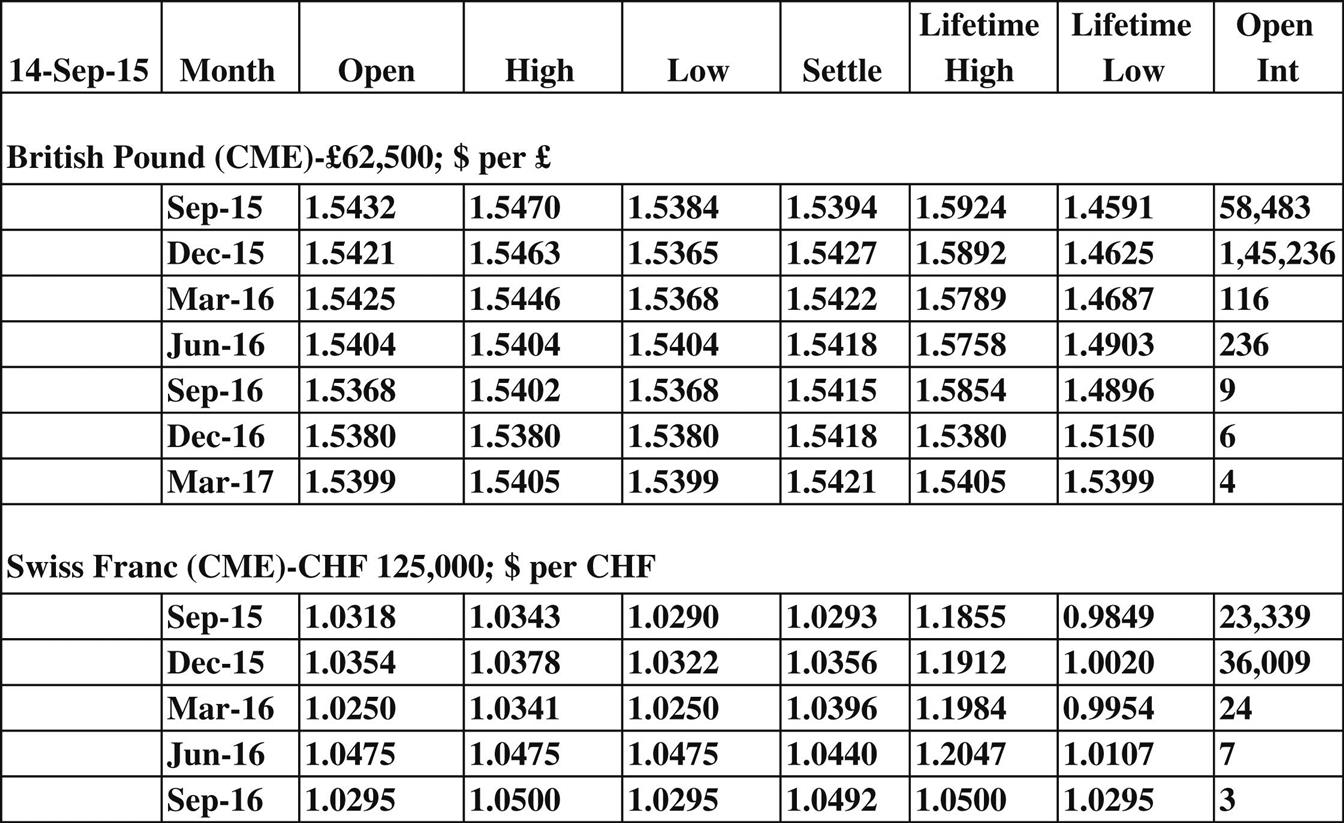

What options does the importer have with respect to payment? One option is to wait 3 months and then buy the francs. A disadvantage of this strategy is that the exchange rate could change over the next 3 months in a way that makes the deal unprofitable. Looking at Fig. 4.1, we see that the current spot rate is CHF0.9937 per $1, or CHF100,000=$100,634 (100,000/0.9937). But there is no guarantee that this exchange rate (and the consequent dollar value of the contract) will prevail in the future. If the dollar were to depreciate against the franc, then it would take more dollars to buy any given quantity of francs. For instance, suppose that 3 months later the future spot rate (which is currently unknown) is CHF0.75=$1. Then it would take $133,333 to purchase CHF100,000, and the watch purchase would not be as profitable for the importer. Of course, if the dollar were to appreciate against the franc, then the profits would be larger. As a result of this uncertainty regarding the dollar/franc exchange rate in the future, the importer may not want to choose the strategy of waiting 3 months to buy francs.

An alternative is to buy the francs now and hold or invest them for 3 months. This alternative has the advantage that the importer knows exactly how many dollars are needed now to buy CHF100,000. But the importer is faced with a new problem of coming up with cash now and investing the francs for 3 months. Another alternative that ensures a certain dollar price of francs is using the forward exchange market. As will be shown in Chapter 6, Exchange Rates, Interest Rates, and Interest Parity, there is a close relationship between the forward market and the former alternative of buying francs now and investing them for 3 months. For now, we will focus on the operation of the forward market.

Forward Rates

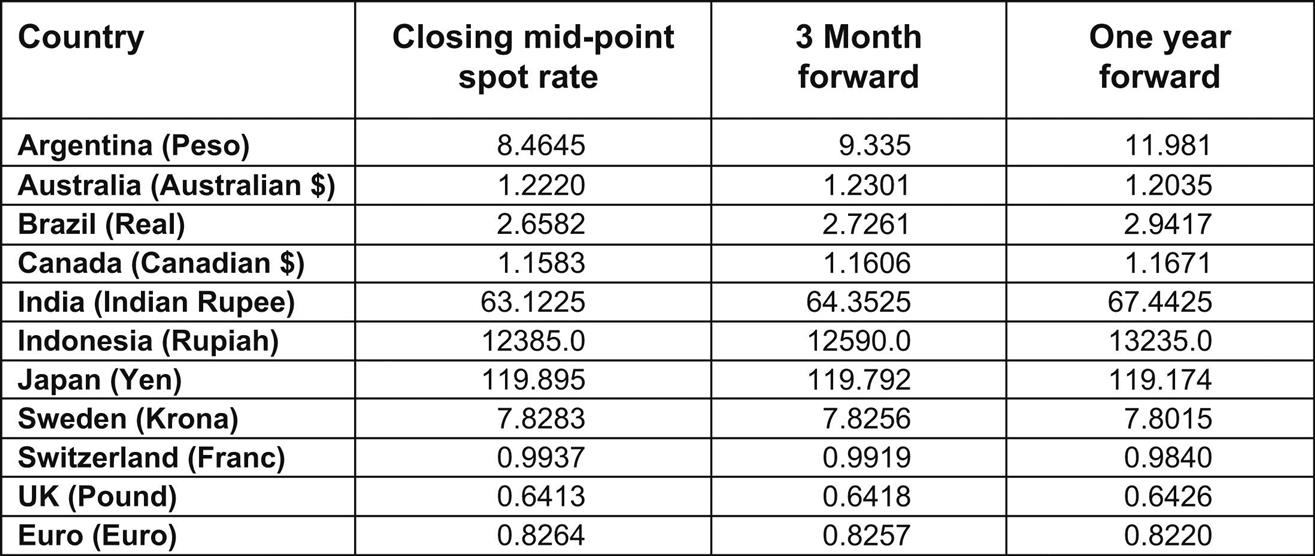

The forward exchange market refers to buying and selling currencies to be delivered at a future date. Fig. 4.1 includes forward exchange rates for the major traded currencies, including the Swiss franc. Most countries in the world have forward markets and maturities and amounts are set in each transaction. Thus, this figure only represents a small selection of the available quotes. Note in the figure that the 3-month or 90-day forward rate on the Swiss franc is CHF0.9919=$1. Note that Fig. 4.1 also shows 1-year forwards. Often 1-month and 6-month forward rates are also quoted, as these are also commonly traded maturities.

The advantage of the forward market is that we have established a set exchange rate between the dollar and the franc and do not have to buy the francs until they are needed in 90 days. This may be preferred to the option of buying francs now and investing them for 3 months, because it is neither necessary to part with any funds now nor to have knowledge of investment opportunities in francs. (However, the selling bank may require that the importer hold “compensating balances” or “margin” until the 90-day period is up—that is, leave funds in an account at the bank, allowing the bank to use the money until the forward date.) With a forward rate of $1.00817=CHF1 (1/0.9919), CHF100,000 will sell for $100,817. The importer now knows with certainty how many dollars the watches will cost in 90 days. In addition, note that the importer only pays a small amount above the spot exchange rate for this forward contract. Instead of paying $100,634 for 100,000 Swiss franc in the spot market, the importer can pay an additional $183 for a contract that delivers the CHF100,000 in 90 days.

If the forward exchange price of a currency exceeds the current spot price, that currency is said to be selling at a forward premium. A currency is selling at a forward discount when the forward rate is less than the current spot rate. The forward rates in Fig. 4.1 indicate that the British pound is selling at a discount against the dollar, but the Japanese yen is selling at a premium. A forward premium or discount is expressed in annualized percent terms to make it comparable to interest rates. In the above case of the Swiss franc, the franc has a forward premium of 0.725 percent. To compute this we find the expected percent change [(Ft-St)/St]*100 and then multiply it by 4 to annualize the results. Note that the result will indicate a negative result, but that refers to the dollar, because the exchange rates in Table 4.1 are in terms of foreign currency per dollar. Thus there is a discount of 0.725 percent on the dollar and a premium of 0.725 percent on the Swiss franc. The implications of a currency selling at a discount or premium will be explored in coming chapters. In the event that the spot and forward rates are equal, the currency is said to be flat.

Table 4.1

Foreign exchange market turnover

| Average daily turnover (billions of US dollars) | ||||||

| Instrument | 2001 | 2004 | 2007 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 |

| Spot transactions | 386 | 631 | 1,005 | 1,488 | 2,046 | 1,654 |

| Outright forwards | 130 | 209 | 362 | 475 | 679 | 700 |

| Foreign exchange swaps | 656 | 954 | 1,714 | 1,759 | 2,239 | 2,383 |

| Currency swaps | 7 | 21 | 31 | 43 | 54 | 96 |

| FX options and other products | 60 | 119 | 212 | 207 | 337 | 254 |

| Total foreign exchange instruments | 1,239 | 1,934 | 3,324 | 3,971 | 5,355 | 5,087 |

Source: Bank for International Settlements, Triennial Central Bank Survey, September 2016.

Swaps

A foreign exchange swap is an arrangement where there is a simultaneous exchange of two currencies on a specific date at a rate agreed at the time of the contract, and a reverse exchange of the same two currencies at a date further in the future at a rate agreed at the time of the contract. Swaps are an efficient way to meet the firm’s need for foreign currencies because they combine two separate transactions into one, thus cutting transactions costs in half. The firm avoids any foreign exchange risk by matching the liability created by borrowing foreign currencies with the asset created by lending domestic currency, both to be repaid at the known future exchange rate. This is known as hedging the foreign exchange risk.

For example, suppose Citibank wants pounds now, and wants to hold the pounds for 3 months. Instead of borrowing the pounds, Citibank could enter into a swap agreement wherein they trade dollars for pounds now and pounds for dollars in 3 months. The terms of the arrangement are obviously closely related to conditions in the forward market, since the swap rates will be determined by the discounts or premiums in the forward exchange market.

Suppose Citibank wants pounds for 3 months and works a swap with HSBC. Citibank will trade dollars to HSBC and in return will receive pounds. In 3 months the trade is reversed. Citibank will payout pounds to HSBC and receive dollars (of course, there is nothing special about the 3-month period used here—swaps could be for any period). Suppose the spot rate is $/£=$2.00 and the 3-month forward rate is $/£=$2.10, so that there is a $0.10 premium on the pound. These premiums or discounts are actually quoted in basis points when serving as swap rates (a basis point is 1/100%, or 0.0001). Thus the $0.10 premium converts into a swap rate of 1000 points, which is all the swap participants are interested in; they do not care about the actual spot or forward rate since only the difference between them matters for a swap.

Swap rates are usefully converted into percent per annum terms to make them comparable to other borrowing and lending rates (remember a swap is the same as borrowing one currency while lending another currency for the duration of the swap period). The swap rate of 1000 points or 0.1000 was for a 3-month period. To convert this into annual terms, we find the percentage return for the swap period and then multiply this by the reciprocal of the fraction of the year for which the swap exists. The percentage return for the swap period is equal to the

The fraction of a year for which the swap exists is

And the reciprocal of the fraction is

Thus, the percent per annum premium (discount) or swap rate is

This swap, then, yields a return of 20% per annum, which can be compared to the other opportunities open to the bank.

An alternative swap agreement is a currency swap. A currency swap is a contract in which two counterparties exchange streams of interest payments in different currencies for an agreed period of time and then exchange principal amounts in the respective currencies at an agreed exchange rate at maturity. Currency swaps allow firms to obtain long-term foreign currency financing at lower cost than they can by borrowing directly. Suppose a Canadian firm wants to receive Japanese yen today with repayment in 5 years. If the Canadian firm is not well known to Japanese banks, the firm will pay a higher interest rate than firms that actively participate in Japanese financial markets. The Canadian firm may approach a bank to arrange a currency swap that will reduce its borrowing costs. The bank will find a Japanese firm desiring Canadian dollars. The Canadian firm is able to borrow Canadian dollars more cheaply than the Japanese firm, and the Japanese firm is able to borrow yen more cheaply than the Canadian firm. The intermediary bank will arrange for each firm to borrow its domestic currency and then swap the domestic currency for the desired foreign currency. The interest rates paid on the two currencies will reflect the forward premium in existence at the time the swap is executed. When the swap agreement matures, the original principal amounts are traded back to the source firms. Both firms benefit by having access to foreign funds at a lower cost than they could obtain directly.

Table 4.1 presents data on the volume of activity in the foreign exchange market. In 2016 about 33% of the transactions reported by the banks surveyed are spot transactions. Foreign exchange swaps constitute 47% of the business, while currency swaps are quite small. Outright forwards account for around 14%. Thus, foreign exchange swaps have more than three times the volume of outright forwards. Foreign exchange options are relatively small at about 5%.

In foreign exchange trading, the ultimate buyers and sellers of currency do not always trade directly with one another but often use someone in the middle—a broker. If a bank wants to buy a particular currency, several other banks could be contacted for quotes, or the bank representative could input an order with an electronic broker where many banks participate and the best price at the current time among the participating banks is revealed. While trading in the broker’s market is in progress, the names of the banks making bids and offers are not known until a deal is reached. This anonymity may be very important to the trading banks, because it allows banks of different sizes and market positions to trade on an equal footing.

In the electronic brokers market, computer programs take offers to buy and sell from different agents and match them. In addition to the electronic brokers, there are electronic dealing systems. Rather than talking directly over the telephone dealer-to-dealer, computer networks allow for trades to be executed electronically. The use of electronic broker systems varies greatly across countries. Approximately 54% of trading in the United States goes through such networks, compared to 66% in the United Kingdom and 48% in Japan.

Futures

The foreign exchange market we have discussed (spot, forward, and swap transactions) is a global market. Commercial banks, business firms, and governments in various locations buy and sell foreign exchange using telephone and computer systems with no centralized geographical market location. However, additional institutions exist that have not yet been covered, one of which is the foreign exchange futures market. The futures market is a market where foreign currencies may be bought and sold for delivery at a future date. The futures market differs from the forward market in that only a few currencies are traded; moreover, trading occurs in standardized contracts and in a specific geographic location. Note that futures contracts are traded on organized exchanges, such as the International Monetary Market (IMM) of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), which is the largest currency futures market. An exchange facilitates buying and selling and guarantees that all commitments are honored. CME futures are traded on the British pound, Canadian dollar, Japanese yen, Swiss franc, Australian dollar, Mexican peso, and euro. The contracts involve a specific amount of currency to be delivered at specific maturity dates. Contracts mature on the third Wednesday of March, June, September, and December. In the forward market, contracts are typically 30, 90, or 180 days long, but can be for any term agreed by the parties, and are maturing every day of the year. Forward market contracts are written for any amount agreed upon by the parties involved. In the CME futures market the contracts are written for fixed amounts: GBP62,500, CAD100,000, JPY12,500,000, CHF125,000, MXN500,000, and EUR125,000.

The futures table shows the dollar prices quoted for each unit of the contract. In Fig. 4.2 the columns for each contract are:

Month – Month that the contract matures

Open – The price that contract had at the beginning of the trading day

High – The highest price the contract reached during the day

Low – The lowest price the contract reached during the day

Settle – The price the contract had at closing of the day

Lifetime High – The highest price the contract has reached at any point during the contract life

Lifetime Low – The lowest price the contract has reached at any point during the contract life

The futures markets provide a hedging facility for firms involved in international trade, as well as a speculative opportunity. Speculators will profit when they accurately forecast a future price for a currency that differs significantly (by more than the transaction cost) from the current contract price. For instance, if we believe that in September the pound will sell for $1.70, and the September futures contract is currently priced at $1.5415 (the settle price), we would buy a September contract. To buy a British pound contract we need to pay 1.5415×62,500=$96,343.75. However, we are only obligated to pay that when the contract matures in September. Since the futures exchange guarantees the settlement of all contracts, they request that participants deposit cash to help ensure that the contract will be honored (in forward contracts the bank will know the participants and might not require any security). For example, the exchange might ask for 10% of the contract value, or $9634.38 as a security or margin. The margin is a cushion for potential losses that you may incur on the contract, to make sure you will honor your contract.

Each day the futures market will quote the September contract that we now own, until the maturity date, so the value of the contract changes on a daily basis. At maturity each pound will cost $1.5415, but the contract does not have to be kept until maturity. For example, assume that the price of the pound contract goes to $1.65 in August. We can now sell our contract for $1.65×62,500=$103,125 for a profit of $6,781.25 (less transactions costs), or we can wait and hope that the September rate will be even more favorable. Note also that the security deposit is returned to us if we sell the contract. In contrast, a fall in the value of the pound in August will hurt our financial position. If the pound falls to $1.50 then our pound position is only worth $93,750. If we still believe that the pound price will go up in September then it makes sense to wait and hold onto the contract. In cases when the negative position becomes serious, the seller might be worried that we will not be able to honor the position in September. Therefore, they might ask for more security, for example an extra $2,593.75 to make the total margin $12,228.13. This is called a margin call.

As the preceding examples show, a futures contract may not be held to maturity by the initial purchaser. Only the last holder of the contract has to take delivery of the foreign exchange. Thus, the futures market can be used to hedge risk, but can also be used by speculators. The speculators can take ownership of a fairly large contract with a small initial investment. Thus, speculators can be highly leveraged and have futures contracts worth lots more than the net worth of the individual. This is how Nick Leeson caused Barings Bank to collapse. In a 3-month period Nick bought 20,000 futures contracts worth about 180,000 pounds each. He was speculating that the contracts would increase in value, but instead the contracts lost almost $1 billion (see www.nickleeson.com, for more details.).

In comparing the types of participants in the futures market and forward markets, we have already concluded that futures markets can be used for speculation as well as hedging. In addition, the futures contracts are for smaller amounts of currency than are forward contracts, and therefore serve as a useful hedging vehicle for relatively small firms. Forward contracts are within the realm of wholesale banking activity and are typically used only by large financial institutions and other large business firms that deal in very large amounts of foreign exchange.

The financial crisis of 2008 highlighted another important difference between forwards and futures. When one trades a forward, the counterparty is a bank. As became evident with the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008, banks are subject to credit risk. If the bank that is the counterparty to your forward contract fails during the life of the contract, then the contract will not be honored, leaving you with a foreign exchange risk exposure. In contrast, futures contracts are traded on an exchange and the exchange guarantees the performance of each contract. So to the extent that bank credit risk is important, futures may be attractive relative to forwards.

Options

Besides forward and future contracts, there is an additional market where future foreign currency assets and liabilities may be hedged; it is called the options market. A foreign currency option is a contract that provides the right to buy or sell a given amount of currency at a fixed exchange rate on or before the maturity date (these are known as “American” options; “European” options may be exercised only at maturity). A call option gives the right to buy currency and a put option gives the right to sell. The price at which currency can be bought or sold is called the strike price or exercise price.

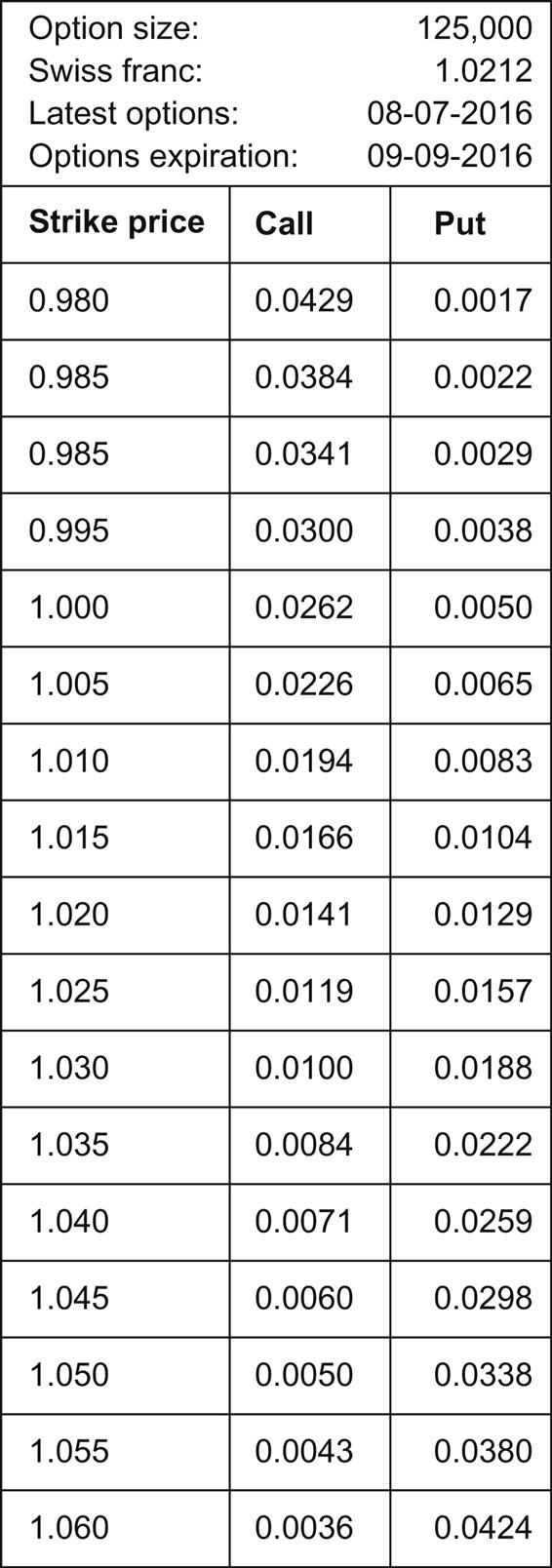

The use of options for hedging purposes is straightforward. Suppose a US importer is buying equipment from a Swiss manufacturer, with a CHF1 million payment due in September. The importer can hedge against a franc appreciation by buying a call option that confers the right to purchase francs until the September maturity, at a specified price. To find the right contract, the US importer has a large choice of strike prices to choose from. Fig. 4.3 shows the options prices for a CHF125,000 contract. Note that contracts are in fixed amounts with fixed maturity dates, just like the futures contracts on organized exchanges like the Philadelphia Exchange. However, large multinational firms often buy options directly from banks. Such custom options may be for any size or date agreed to and therefore provide greater flexibility than is possible on organized exchanges.

Fig. 4.3 shows the options quotes for the Swiss franc contract that matures in September, 2016. The quotes are from July 8, 2016 when the spot Swiss franc value was $1.0212. The first column in the figure shows the strike prices available. Each strike price has a cost in terms of dollars per Swiss franc for a call or put option in the remaining columns. For example, a put option would be quoted in the third column.

Returning to our trader who has a payment of CHF1 million in September, the liability in September is presently costing the company $1,021,200 (CHF1 million @ $1.0212). If the franc appreciated to $1.10 over the next 3 months, then using the spot market in 3 months would change the value of the imports to $1,100,000 (CHF1,000,000×$1.1), an increase in the cost of the imports of $78,800. A call option will provide insurance against such change. But there are many options to choose from. If we are only interested in a substantial increase in the value of the Swiss franc, we should choose a higher strike price because it is cheaper. If we cannot tolerate much movement at all, we would pick a lower strike price, but be willing to pay a higher upfront cost. For example, if we choose to protect ourselves against a substantial movement in the Swiss franc we might choose 1.060 as a strike price. This strike price would give us the right to buy Swiss francs at $1.06. It will cost us $0.0036 per Swiss franc. Thus, the CHF125,000 contract would cost us $450 (0.0036 ×125,000). However, we need eight contracts to cover our liability so the total cost for the option cover is $3,600.

With the options contract, we can now avoid any increase in the cost of the currency above 1.06, and at the same time take advantage of any reduction in the cost of the Swiss franc. For example, if the Swiss franc next month falls in value to $1.00, we can let the option expire and buy Swiss francs on the spot market at a cost of $1,000,000, a savings of $21,200 from our initial liability. But having the option not to exercise the trade comes at a cost. Even if we do not exercise the option contract, we still have to pay the full amount of the option premium of $3,600.

An option is said to be in the money when the strike price is less than the current spot rate for a call option, or greater than the current spot rate for a put option. Returning to our example of the US importer buying CHF1 million of equipment to be paid for in September, the current spot rate is $1.0212 per CHF. If the importer buys a September call option with a strike price of 1.010, then this contract can already be exercised to buy cheap currency. By exercising the option the importer can already buy Swiss francs at $1.01, and could then turn around and sell them on the spot market for $1.0212. This type of contract is “in the money” and would cost more than a contract that is not “in the money.” Similarly a strike price that is above the current spot rate would be “in the money” for a put option.

If we knew with certainty what the future exchange rate would be, there would be no market for options, futures, or forward contracts. In an uncertain world, risk-averse traders willingly pay to avoid the potential loss associated with adverse movements in exchange rates. An advantage of options over futures or forwards is greater flexibility. A futures or forward contract is an obligation to buy or sell at a set exchange rate. An option offers the right to buy or sell if desired in the future and is not an obligation.

Other Forward-Looking Instruments

The growth of options contracts since the early 1980s has stimulated the development of new products and techniques for managing foreign exchange assets and liabilities. One recent development combines the features of a forward contract and an option contract. Terms such as break forward, participating forward, or FOX (forward with option exit) refer to forward contracts with an option to break out of the contract at a future date. In this case, the forward exchange rate price includes an option premium for the right to break the forward contract. The incentive for such a contract comes from the desire of customers to have the insurance provided by a forward contract when the exchange rate moves against them and yet not lose the potential for profit available with favorable exchange rate movements.

One might first wonder whether a break-forward hedge could not be achieved more simply by using a straight option contract. There are several attractive features of the break-forward contract that do not exist with an option. For one thing, an option requires an upfront premium payment. The corporate treasurer may not have a budget for option premiums or may not have management approval for using options. The break forward hides the option premium in the forward rate. Since the price at which the forward contract is broken is fixed in advance, the break forward may be treated as a simple forward contract for tax and accounting purposes, whether the contract is broken or not.

One of the more difficult problems in hedging foreign exchange risk arises in bidding on contracts. The bidder submits a proposal to perform some task for the firm or government agency that will award a contract to the successful bidder. Since there may be many other bidders, the bidding firms face the foreign exchange risk associated with the contract only if they are, in fact, awarded the contract. Suppose a particular bidder assesses that it has only a 20% chance of winning the contract. Should that bidder buy a forward contract or option today to hedge the foreign exchange risk it faces in the event it is the successful bidder? If substantial foreign exchange risk is involved for the successful bidder, then not only the bidders but also the contract awarder face a dilemma. The bids will not be as competitive in light of the outstanding foreign exchange risk as they would be if the exchange rate uncertainty were hedged.

One approach to this problem is the Scout contract. Midland Bank developed the Scout (share currency option under tender) as an option that is sold to the contract awarder, who then sells it to the successful bidder. The awarding agency now receives more competitive, and perhaps a greater number of, bids because the bidders now know that the foreign exchange hedge is arranged.

Over time, we should expect a proliferation of new financial market products aimed at dealing with future transactions involving foreign exchange. If there is a corporate interest in customizing an option or a forward arrangement to a specific type of transaction, an innovative bank will step in and offer a product. The small sample of new products discussed in this section is intended to suggest the practical use of these financial innovations.

Summary

1. Many international transactions involve future delivery of goods and payments, subjecting traders to uncertainty about future exchange rate fluctuations at the time of delivery. Therefore, several forward-looking market instruments exist to reduce traders’ currency risk.

2. The forward exchange market is composed of commercial banks buying and selling foreign currencies to be delivered at a future date.

3. When the forward price of a currency is greater than (less than) the spot price, the currency is said to sell at a forward premium (discount). When the forward price is equal to the spot price, a currency is sold at a forward flat.

4. The advantage of the forward exchange market is that a specified exchange rate between currencies has been established and no buying/selling of the currency is needed until a specified date in the future.

5. The forward exchange swap is a combination of spot and forward transactions of the same amount of the currency delivered in two different dates. The two steps are executed in one single step.

6. The currency swap is a contract between two parties to exchange the principal and interest payments of a loan in one currency to the equivalent term of loan in another currency. Both parties benefit from having access to a long-term foreign currency financing at a lower cost than they could obtain directly.

7. Foreign currency futures are standardized contracts traded on established exchanges for delivery of currencies at a specified future date.

8. The futures market differs from the forward market in that only a few currencies are traded; each currency has a standardized contract of a fixed amount and predetermined dates; and contracts are traded only in a specific location. The participants in the futures market also include speculators, since the future contracts can be bought and sold before the contracts mature.

9. Foreign currency options are contracts that give the buyer the right to buy (call option) or sell (put option) currencies at a specified price within a specific period of time. The strike price is the price at which the owner of the contract has the right to transact.

Exercises

1. Use Fig. 4.1 to determine whether each of the currencies listed here is selling at a 3-month forward premium or discount against the dollar:

2. Calculate the per annum premium (discount) of a 3-month forward contract on Canadian dollars based on the information in Fig. 4.1.

3. List at least three ways in which a futures contract differs from a forward contract.

4. Assume US corporation XYZ needs to arrange to have £10,000 in 90 days. Discuss the alternatives available to the corporation in meeting this obligation. What factors are important in determining which strategy is best?

5. Suppose you are the treasurer of a large US multinational firm that wants to hedge the foreign exchange risk associated with a payable of 1,000,000 UK pound due in 90 days. How many futures contracts would cover your risk?

6. Suppose you are the treasurer of a US multinational firm that wants to hedge the foreign exchange risk associated with your firm’s sale of equipment to a Swiss firm worth CHF1,000,000. The receivable is due in 6 months. You want to ensure that Swiss francs are worth at least $0.90 when the francs are received so you want a strike price of $0.90. How many options contracts do you need to hedge this risk? Do you want a call or put on Swiss francs? What has to happen to the spot rate in 6 months for you to let the option expire?