Financial Management of the Multinational Firm

Abstract

Since multinational firms are involved in payables and receivables denominated in different currencies, product shipments across national borders, and subsidiaries operating in different political jurisdictions, they face a different set of problems than firms with a purely domestic operation. This chapter looks at the unique attributes of financial management in the multinational firm. Various methods of exercising financial control over foreign operations are covered, emphasizing the particular issues facing multinational companies, such as whether foreign subsidiary profits should be measured and evaluated in foreign currency or domestic currency of the parent company. The challenge of cash management for different currencies is addressed, including dealing with the different financial market regulations and institutions of different countries; real-world examples demonstrate the principles discussed. Letters of credit (LOCs) are defined and discussed in detail, as well as trade financing, intrafirm transfers, and capital budgeting.

Keywords

Adjusted present value; APV; arm’s-length pricing; bill of lading; international financial management; intrafirm fund transfers; import transactions; irrevocable letter of credit; letter of credit; liquid asset; LOC; multinational cash management; multinational company; netting; revocable letter of credit

Since multinational firms are involved in payables and receivables denominated in different currencies, product shipments across national borders, and subsidiaries operating in different political jurisdictions, they face a different set of problems than firms with a purely domestic operation. The corporate treasurer and other financial decision makers of the multinational firms operate in a cosmopolitan setting that offers profit and loss opportunities never considered by the executives of purely domestic firms. This chapter looks at the unique attributes of financial management in the multinational firm. The basic issues—control, cash management, trade credit, intrafirm transfers, and capital budgeting—face all firms. The problems particular to the internationally oriented firm are the ones addressed.

Financial Control

Any business firm must evaluate its operations periodically to better allocate resources and increase income. The financial management of a multinational firm involves exercising control over foreign operations. The responsible individuals at the parent office or headquarters review financial reports from foreign subsidiaries with a view toward modifying operations and assessing the performance of foreign managers.

Typical control systems are based on setting standards with regard to sales, profits, inventory, or other specific variables and then examining financial statements and reports to evaluate the achievement of such goals. There is no “correct” system of control. Methods vary across industries and even across firms in a single industry. All methods have the common goal of providing management with a means of monitoring the performance of the firm’s operations, new strategies, and goals as conditions change. However, establishing a useful control system is more difficult for a multinational firm than for a purely domestic firm. For instance, should foreign subsidiary profits be measured and evaluated in foreign currency or in the domestic currency of the parent firm? The answer to this question depends on whether foreign managers are to be held responsible for currency translation gains or losses.

If top management wants foreign managers to be involved in currency management and international financing issues, then the domestic currency of the parent would be a reasonable choice. On the other hand, if top management wants foreign managers to concern themselves with production operations and behave as other managers in companies in the foreign country would, then the foreign currency would be the appropriate currency for evaluation.

Some multinational firms prefer a decentralized management structure in which each subsidiary has a great deal of autonomy and makes most financing and production decisions subject only to general parent company guidelines. In this management setting, the foreign manager may be expected to operate and think as the stockholders of the parent firm would want, so the foreign manager makes decisions aimed at increasing the parent’s domestic currency value of the subsidiary. The control mechanism in such firms is to evaluate foreign managers based on their ability to increase that value.

Other firms prefer more centralized management in which financial managers at the parent make most of the decisions. They choose to move funds among divisions based on a system-wide view rather than what is best for a single subsidiary. A highly centralized system would have foreign managers evaluated on their ability to meet goals established by the parent for key variables like sales or labor costs. The parent-firm managers assume responsibility for maximizing the value of the firm, with foreign managers basically responding to directives from the top. We then see that the appropriate control system is largely determined by the management style of the parent.

Considering the discussion to this point, it is clear that managers at foreign subsidiaries should be evaluated only on the basis of things they control. Foreign managers often may be asked by the parent to follow policies and relations with other subsidiaries of the firm that the managers would never follow if they sought solely to maximize their subsidiary’s profit. Actions of the parent that lower a subsidiary’s profit should not result in a negative view of the foreign manager. In addition, other actions beyond the foreign manager’s control—changing tax laws, foreign exchange controls, or inflation rates—could result in reducing foreign profits through no fault of the foreign manager. The message to parent company managers is to place blame fairly where the blame lies. In a dynamic world, corporate fortunes may rise and fall because of events entirely beyond any manager’s control.

Cash Management

Cash management involves using the firm’s cash as efficiently as possible. Given the daily uncertainties of business, firms must maintain some liquid resources. Liquid assets are those that are readily spent. Cash is the most liquid asset. But since cash (and the traditional checking account) earns no interest, the firm has a strong incentive to minimize its holdings of cash. There are highly liquid short-term securities that serve as good substitutes for actual cash balances and yet pay interest. The corporate treasurer is concerned with maintaining the correct level of liquidity at the minimum possible cost.

The multinational treasurer faces the challenge of managing liquid assets denominated in different currencies. The challenge is compounded by the fact that subsidiaries operate in foreign countries where financial market regulations and institutions differ.

When a subsidiary receives a payment and the funds are not needed immediately by this subsidiary, the managers at the parent headquarters must decide what to do with the funds. For instance, suppose a US multinational’s Mexican subsidiary receives 500 million pesos. Should the pesos be converted to dollars and invested in the United States, or placed in Mexican peso investments, or converted into any other currency in the world? The answer depends on the current needs of the firm as well as the current regulations in Mexico. If Mexico has strict foreign exchange controls in place, the 500 million pesos will have to be kept in Mexico and invested there until a future time when the Mexican subsidiary will need them to make a payment.

Even without legal restrictions on foreign exchange movements, we might invest the pesos in Mexico for 30 days if the subsidiary faces a large payment in 30 days. This assumes that there is no need for the funds in another area of the firm, and that the return on the Mexican investment is comparable to what we could earn in another country on a similar investment (which interest rate parity would suggest). By leaving the funds in pesos, we do not incur any transaction costs for converting pesos to another currency now and then going back to pesos in 30 days. In any case, we would never let the funds sit idly in the bank for 30 days.

There are times when the political or economic situation in a country is so unstable that we keep only the minimum possible level of assets in that country. Even when we will need pesos in 30 days for the Mexican subsidiary’s payable, if there exists a significant threat that the government could confiscate or freeze bank deposits or other financial assets, we would incur the transaction costs of currency conversion to avoid the political risk associated with leaving the money in Mexico.

Multinational cash management involves centralized management. Subsidiaries and liquid assets may be spread around the world, but they are managed from the home office of the parent firm. Through such centralized coordination, the overall cash needs of the firm are lower. This occurs because all subsidiaries do not have the same pattern of cash flows. For instance, one subsidiary may receive a dollar payment and finds itself with surplus cash, while another subsidiary faces a dollar payment and must obtain dollars. If each subsidiary operated independently, there would be more cash held in the family of multinational foreign units than if the parent headquarters directed the surplus funds of one subsidiary to the subsidiary facing the payable.

Centralization of cash management allows the parent to offset subsidiary payables and receivables in a process called netting. Netting involves the consolidation of payables and receivables for one currency so that only the difference between them must be bought or sold. For example, suppose Oklahoma Instruments in the United States sells C$2 million worth of car phones to its Canadian sales subsidiary and buys C$3 million worth of computer frames from its Canadian manufacturing subsidiary. If the payable and receivable both are due on the same day, then the C$2 million receivable can be used to fund the C$3 million payable, and only C$1 million must be bought in the foreign exchange market. Rather than buy C$3 million to settle the payable and sell the C$2 million to convert the receivable into dollars, incurring transaction costs twice on the full C$5 million, the firm has one foreign exchange transaction for C$1 million.

Had the two Canadian operations not been subsidiaries, the financial managers would still practice netting but on a corporate-wide basis, buying or selling only the net amount of any currency required after aggregating the receivables and payables of all subsidiaries overall currencies. Effective netting requires accurate and timely reporting of transactions by all divisions of the firm.

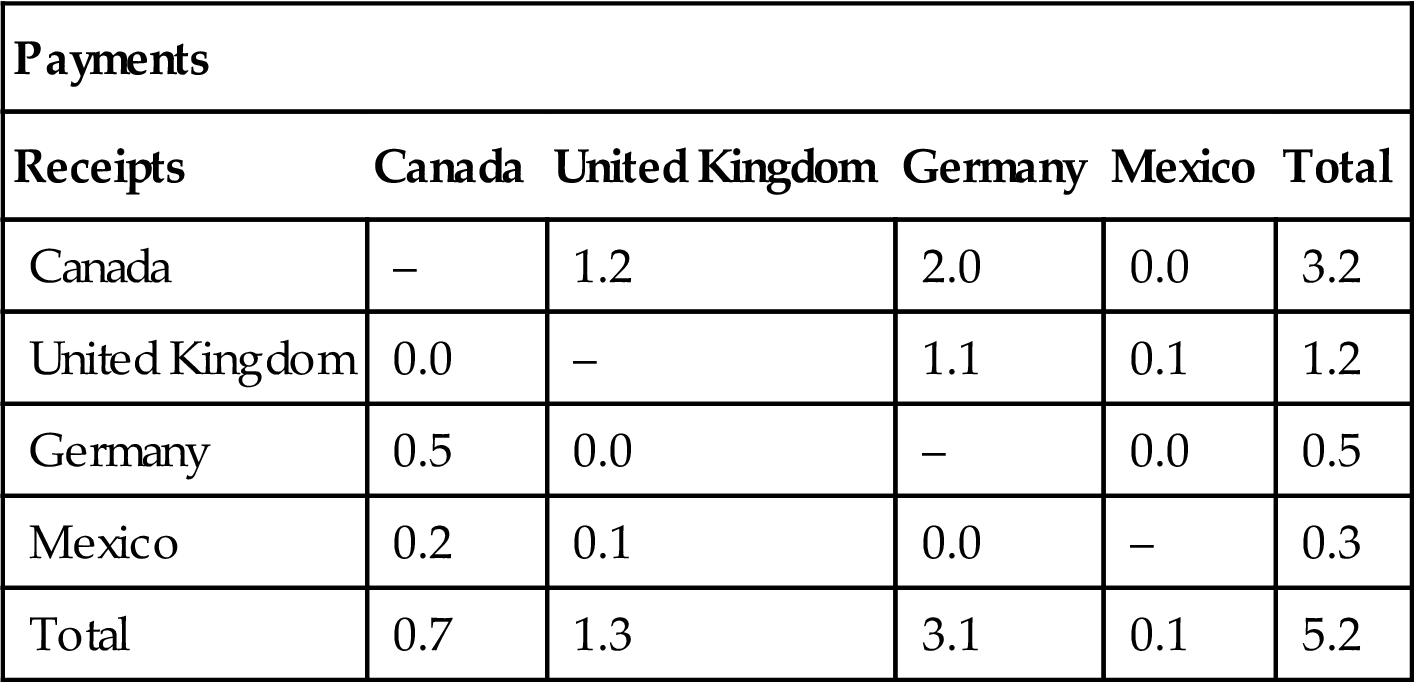

As an example of intrafirm netting, let us consider a US parent firm with subsidiaries in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Mexico. Table 9.1 sets up the report for the week of January 15. We assume that netting occurs weekly. Each division’s scheduled payments and receipts are converted to dollars so that aggregation across all units can occur. Table 9.1 indicates that the Canadian subsidiary will pay $0.7 million (total of column 2) and receive $3.2 million (total of row 1), so it will have a cash surplus of $2.5 million. The UK subsidiary will pay $1.3 million and receive $1.2 million, so it will have a cash shortage of $0.1 million. The German subsidiary will pay $3.1 million and receive $0.5 million, so it has a shortage of $2.6 million, and, finally, the Mexican subsidiary will pay $0.1 million and receive $0.3 million, so it has a surplus of $0.2 million. The parent financial managers determine the net payer or receiver position of each subsidiary for the weekly netting. Only these net amounts are transferred within the firm. The firm does not have to change $0.7 million worth of Canadian dollars into the currencies of Germany and Mexico to settle the payable of the Canadian subsidiary and then convert $3.2 million worth of pounds, euros, and pesos into Canadian dollars. Only the net cash surplus flowing to the Canadian subsidiary of $2.5 million must be converted into Canadian dollars.

Table 9.1

Intrafirm payments for netting million-dollar values (week of January 15)

| Payments | |||||

| Receipts | Canada | United Kingdom | Germany | Mexico | Total |

| Canada | – | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| United Kingdom | 0.0 | – | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Germany | 0.5 | 0.0 | – | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Mexico | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | – | 0.3 |

| Total | 0.7 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 5.2 |

So far we have considered netting when the currency flows occur at the same time. What if the payments and receipts are not for the same date? Suppose in our Oklahoma Instruments example that the C$3 million payable is due on October 1, and the C$2 million receivable is due September 1. Netting could still occur by leading or lagging currency flows. The sales subsidiary could lag its C$2 million payment by 1 month, or the C$3 million could lead 1 month and be paid on September 1. Leads and lags increase the flexibility of parent financial managers, but require excellent information flows between all divisions and headquarters.

Letters of Credit

Once a company decides to export a good, they want to make sure that a payment will be made by the importer of the good. Because it is difficult to enforce contracts across countries, an intermediary is often necessary to enforce the contract. A letter of credit (LOC) is a written instrument issued by a bank at the request of an importer that obligates the bank to pay a specific amount of money to an exporter. The time at which payment is due is specified, along with conditions regarding necessary documents to be presented by the exporter prior to payment. The LOC may stipulate that a bill of lading be presented that evidences no damaged goods. A bill of lading is a detailed list of the content that is shipped, and can be used to identify missing or damaged items. Perhaps some minimal level of damage (like 2% of the boxes or crates) is stipulated. In any case such conditions in an LOC allow the importer to retain some quality control prior to payment.

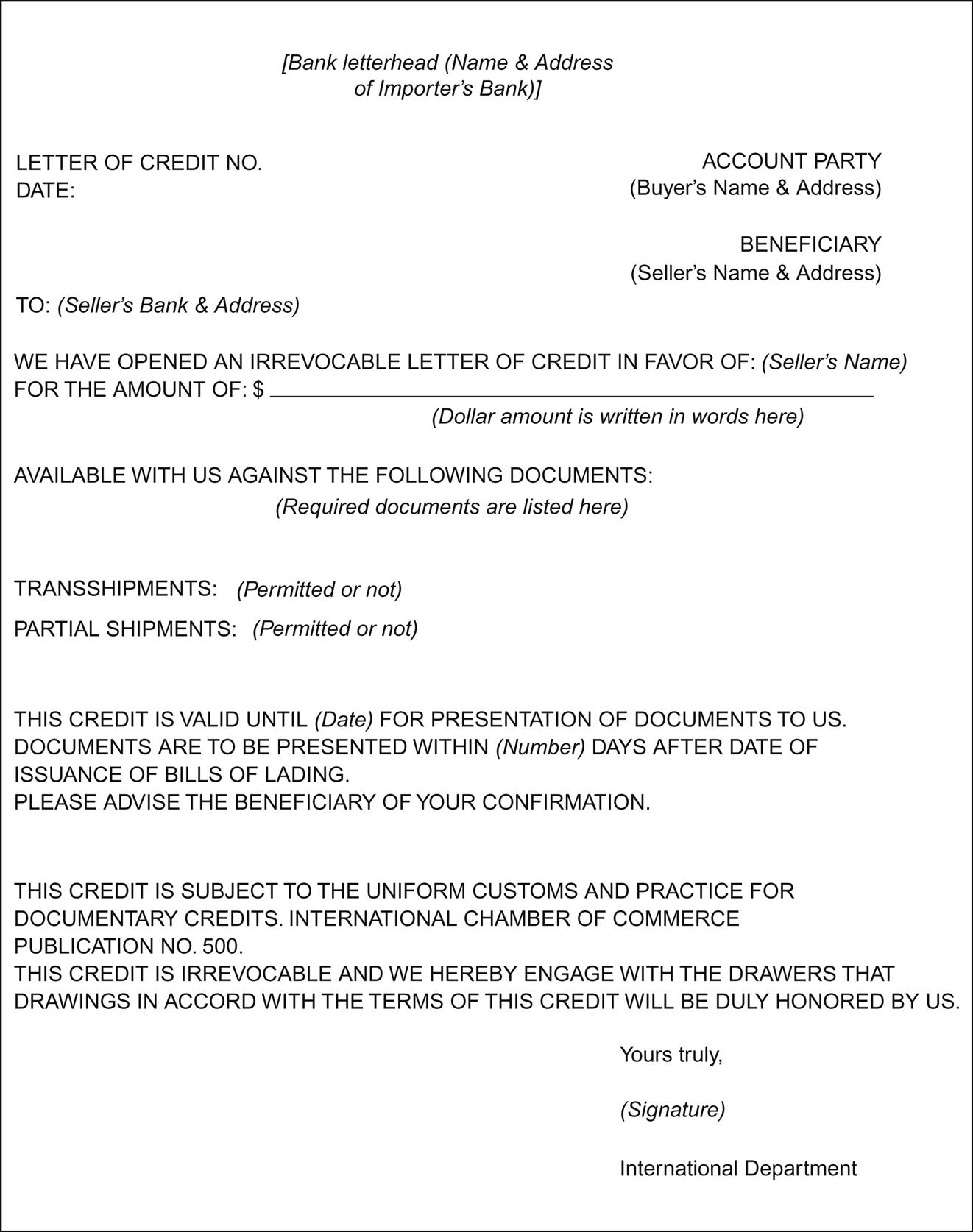

Fig. 9.1 illustrates a simple LOC. Note that this is an irrevocable LOC. This means that the agreement cannot be modified without the express permission of all parties. Most LOCs are of this type. A revocable LOC may be altered by the account party—the importer buying the goods. Since the importer is free to alter the LOC, we might wonder why any exporter would ever accept a revocable LOC. The exporter may interpret the issuance of the LOC as a favorable credit report on the buyer. The exporter will call the issuing bank prior to shipment to make sure that the LOC has not been altered or revoked, and then present the necessary documents and collect payment as soon as possible. The revocable LOC is still safer than shipping goods based only on the importer’s promise to pay, with no bank credit backing up the transaction. Still revocable LOCs primarily are used only when there is no question of revocation. This form of LOC may save bank fees, which are higher with irrevocable LOCs; so if there is no chance of revocation, it may pay to use the revocable LOC.

The sales contract stipulates the method of payment. The use of LOCs is widespread, so let us assume the contract calls for payment by LOC. The importer must then apply for an LOC from a bank. The importer requests that the LOC stipulate no payment until appropriate documents are presented by the exporter to the bank. These document stipulations cannot violate the sales contract since the bank is at risk to ensure that the documents are in order at the time of payment.

If the bank considers the importer an acceptable credit risk, the LOC is issued and sent to the exporter. The exporter then examines the LOC to ensure that it conforms to the sales contract. If it does not, then modifications must be made before the goods are shipped. Once the exporter fulfills all obligations in delivering the goods, the documentary proof is presented to the bank for examination. If the documents conform to the LOC, payment is made, with the bank collecting from the importer and then paying the exporter.

If the importer does not pay the bank, the bank is still obligated to pay the exporter. The exporter is then satisfied, and any problems must be settled between the importer and the bank. Banks may or may not require that the underlying goods serve as collateral for the LOC. If the bank does require an interest in the goods, then the bill of lading is consigned to the bank. With an unsecured LOC, the bank assumes the credit risk of a buyer default. With a secured LOC, the bank assumes the risk of changes in the value of the goods and the cost of disposal. Even if the importer is a sound credit risk, the bank assumes the risk that it misses a document discrepancy and that the importer refuses to pay as a result.

What are the risks for the buyer and seller? The exporter faces the risk of shipping goods without being able to meet all terms listed in the LOC. If the goods are shipped and a document discrepancy exists, then the seller will not be paid. The buyer risks fraud from the seller. The goods may not meet the specifications ordered, but the seller fraudulently prepares documents stating otherwise. The bank is not responsible for such fraudulent documents, so the risk is the buyer’s.

Banks charge a flat fee for issuing and amending LOCs. A percentage of the amount paid is also charged at the time payment is made. These charges generally apply to the importer, unless the parties agree otherwise.

An Example of Trade Financing

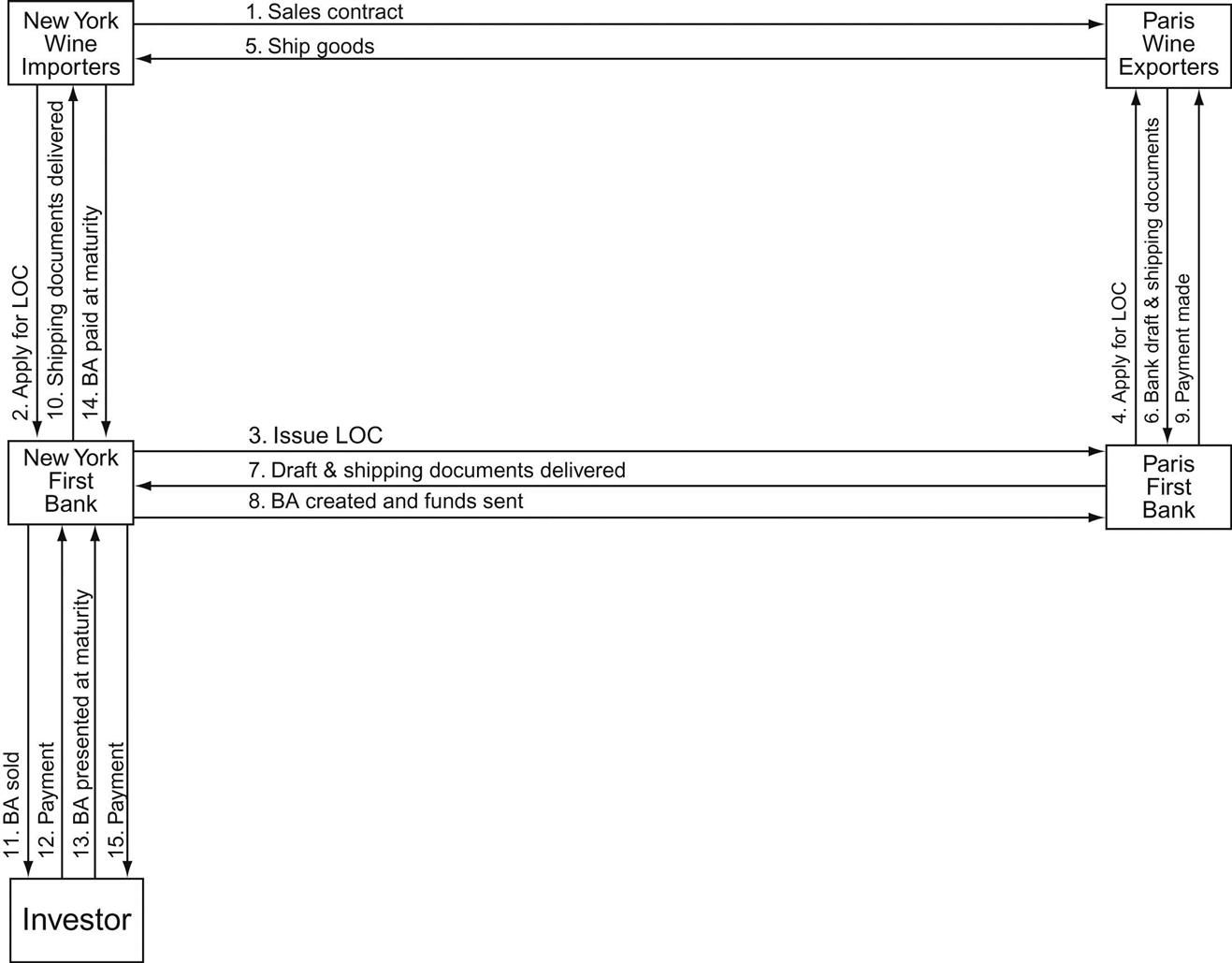

Let us consider an example that applies some of the issues covered so far. Suppose a US firm, New York Wine Importers, wants to import wine from a French firm, Paris Wine Exporters. Fig. 9.2 illustrates the steps involved in the transaction. First, the importer and exporter must agree on the basics of the transaction. The sales contract will stipulate the amount and kind of wine, price, shipping date, and payment method.

Following the sales contract, the importer requests a LOC from its bank, New York First Bank. The bank issues an LOC that authorizes Paris Wine Exporters to draw a bank draft on New York First Bank for payment. The bank draft is like a check, except that it is dated for maturity at some time in the future when payment will be made. Paris Wine Exporters ships the wine and gives its bank, Paris First Bank, the bank draft along with the necessary shipping documents for the wine. Paris First Bank then sends the bank draft, shipping documents, and LOC to New York First Bank.

When New York First Bank accepts the bank draft, a bankers’ acceptance (BA) is created. A banker’s acceptance is a contractual obligation of a bank for a future payment. At this point, Paris Wine Exporters may receive payment of a discounted value of the BA, as the BA does not mature until sometime in the future. New York First Bank discounts the BA and sends the funds to Paris First Bank for the account of Paris Wine Exporters. New York First Bank delivers the shipping documents to New York Wine Importers, and the importer takes possession of the wine.

New York First Bank is now holding the BA after paying a discounted value to Paris First Bank. Instead of holding the BA until maturity, New York First Bank sells it to an investor. Upon maturity, the investor will receive the face value of the BA from New York First Bank, and New York First Bank will receive the face value from New York Wine Importers.

Intrafirm Transfers

Since the multinational firm is made up of subsidiaries located in different political jurisdictions, transferring funds among divisions of the firm often depends on what governments will allow. Beyond the transfer of cash, as covered in the preceding section, the firm will have goods and services moving between subsidiaries. The price that one subsidiary charges another subsidiary for internal goods transfers is called a transfer price. The setting of transfer prices can be a sensitive internal corporate issue because it helps to determine how total firm profits are allocated across divisions. Governments are also interested in transfer pricing since the prices at which goods are transferred will determine tariff and tax revenues.

The parent firm always has an incentive to minimize taxes by pricing transfers in order to keep profits low in high-tax countries and by shifting profits to subsidiaries in low-tax countries. This is done by having intrafirm purchases by the high-tax subsidiary made at artificially high prices, while intrafirm sales by the high-tax subsidiary are made at artificially low prices.

Governments often restrict the ability of multinationals to use transfer pricing to minimize taxes. The US Internal Revenue Code requires arm’s-length pricing between subsidiaries—charging prices that an unrelated buyer and seller would willingly pay. When tariffs are collected on the value of trade, the multinational has the incentive to assign artificially low prices to goods moving between subsidiaries. Customs officials may determine that a shipment is being “underinvoiced” and may assign a value that more truly reflects the market value of the goods.

Transfer pricing may also be used for “window-dressing”—i.e., to improve the apparent profitability of a subsidiary. This may be done to allow the subsidiary to borrow at more favorable terms, since its credit rating will be upgraded as a result of the increased profitability. The higher profits can be created by paying the subsidiary artificially high prices for its products in intrafirm transactions. The firm that uses transfer pricing to shift profits from one subsidiary to another introduces an additional problem for financial control. It is important that the firm be able to evaluate each subsidiary on the basis of its contribution to corporate income. Any artificial distortion of profits should be accounted for so that corporate resources are efficiently allocated.

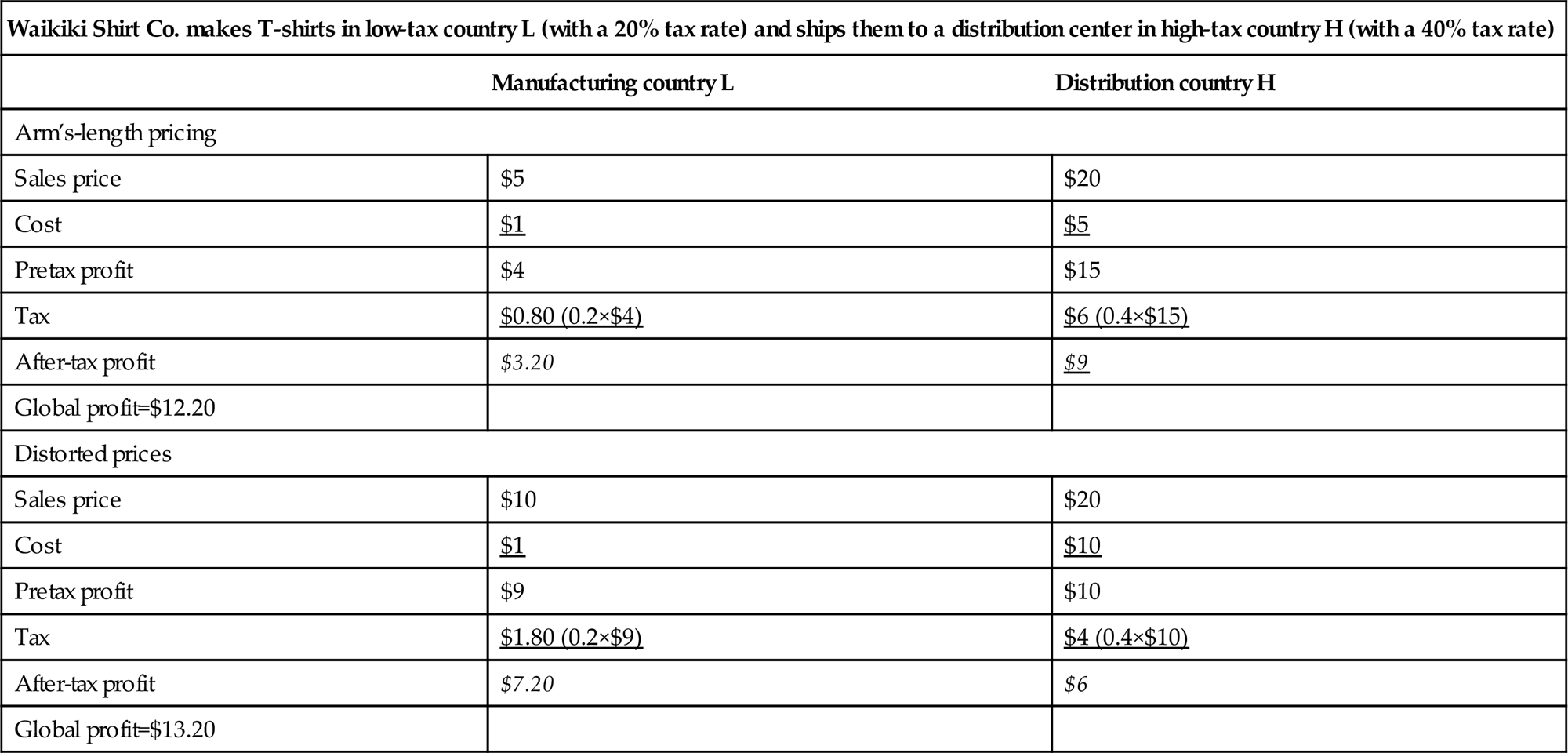

Table 9.2 provides an example of transfer pricing for the Waikiki Shirt Co. Waikiki Shirt Co. manufactures shirts in a low-tax country, country L, and then ships the shirts to a distribution center in a high-tax country, country H. The tax rate in L is 20% and the tax rate in H is 40%. Given these differential tax rates, Waikiki Shirt Co. will increase its global profit if profits earned by the high-tax distribution operation in country H are transferred to country L, where they would be taxed at a lower rate. The top half of the table provides the outcome when the firm uses arm’s-length pricing in transferring shirts from the manufacturing operation to the distribution operation. The manufactured shirts produced in country L are sold to the distribution operation in country H at a price of $5. Since shirts cost $1 to produce, the pretax profit in country L is $4 per shirt. With a tax rate of 20%, there is a tax of $0.80 per shirt so that the after-tax profit of the manufacturing operation is $3.20. The distribution center pays $5 per shirt and then sells the shirts for $20, earning a pretax profit of $15 per shirt. With a 40% tax rate in country H, the firm must pay $6 tax per shirt so that the after-tax profit is $9 per shirt. By summing the after-tax profit earned in countries L and H, the firm earns a global profit of $12.20 per shirt.

Table 9.2

| Waikiki Shirt Co. makes T-shirts in low-tax country L (with a 20% tax rate) and ships them to a distribution center in high-tax country H (with a 40% tax rate) | ||

| Manufacturing country L | Distribution country H | |

| Arm’s-length pricing | ||

| Sales price | $5 | $20 |

| Cost | $1 | $5 |

| Pretax profit | $4 | $15 |

| Tax | $0.80 (0.2×$4) | $6 (0.4×$15) |

| After-tax profit | $3.20 | $9 |

| Global profit=$12.20 | ||

| Distorted prices | ||

| Sales price | $10 | $20 |

| Cost | $1 | $10 |

| Pretax profit | $9 | $10 |

| Tax | $1.80 (0.2×$9) | $4 (0.4×$10) |

| After-tax profit | $7.20 | $6 |

| Global profit=$13.20 | ||

Now suppose the firm uses distorted transfer pricing to lower the global tax liability and increase the global profit. This involves having the manufacturing operation in the low-tax country L charge a price above the arm’s-length (true market) value for the shirts it sells to the distribution operation in the high-tax country H. The bottom half of Table 9.2 illustrates how this might work. Now the manufacturing operation sells the shirts to the distribution operation for $10 per shirt. The cost of production is still the same $1 so the pretax profit is $9 per shirt. A 20% tax rate means that a tax of $1.80 per shirt must be paid, and the after-tax profit is $7.20 per shirt. The distribution operation now pays $10 for the shirt and still sells it for $20, so the pretax profit is $10. At 40%, the tax is $4 per shirt, and the after-tax profit is $6. Summing the after-tax profit of the operations in country L and country H, we find that the global profit is $13.20 per shirt.

The firm is able to increase the profit per shirt by $1 through the transfer pricing distortion of the value of the shirt transferred from country L to country H. In this manner, firms can increase profits by shifting profits from high-tax to low-tax countries. Of course, the tax authorities in country H would not permit such an overstatement of the transfer value of the shirt (and consequent underpayment of taxes in country H), if they could determine the true arm’s-length shirt value. For this reason, tax authorities frequently ask multinational firms to justify the prices they use for internal transfers.

Capital Budgeting

Capital budgeting refers to the evaluation of prospective investment alternatives and the commitment of funds to preferred projects. Long-term commitments of funds expected to provide cash flows extending beyond 1 year are called capital expenditures. Capital expenditures are made to acquire capital assets, like machines or factories or whole companies. Since such long-term commitments often involve large sums of money, careful planning is required to determine which capital assets to acquire. Plans for capital expenditures are usually summarized in a capital budget.

Multinational firms considering foreign investment opportunities face a more complex problem than do firms considering only domestic investments. Foreign projects involve foreign exchange risk, political risk, and foreign tax regulations. Comparing projects in different countries requires a consideration of how all factors will change over countries.

There are several alternative approaches to capital budgeting. A useful approach for multinational firms is the adjusted present value approach. We work with present value because the value of a dollar to be received today is worth more than a dollar to be received in the future, say 1 year from now. As a result we must discount future cash flows to reflect the fact that the value today will fall depending on how long it takes before the cash flows are realized. The Appendix A to this chapter reviews present value calculations for readers unfamiliar with the concept.

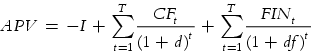

For multinational firms, the adjusted present value approach is presented here as an appropriate tool for capital budgeting decisions. The adjusted present value (APV) measures total present value as the sum of the present values of the basic cash flows estimated to result from the investment (operations flows) plus all financial effects related to the investment, or

(9.1)

(9.1)

(9.1)

where −I is the initial investment or cash outlay, Σ is the summation operator, t indicates time or year when cash flows are realized (t extends from year 1 to year T, where T is the final year), CFt represents estimated basic cash flows in year t resulting from project operations, d is the discount rate on those cash flows, FINt is any additional financial effect on cash flows in year t (these will be discussed shortly), and df is the discount rate applied to the financial effects.

CFt should be estimated on an after-tax basis. Problems of estimation include deciding whether cash flows should be those directed to the subsidiary housing the project, or only to those flows remitted to the parent company. The appropriate combination of cash flows can reduce the taxes of the parent and subsidiary.

Several possible financing effects should be included in FINt. These may include depreciation charges arising from the capital expenditure, financial subsidies, or concessionary credit terms extended to the subsidiary by a government or official agency, deferred or reduced taxes given as incentive to undertake the expenditure, or a new ability to circumvent exchange controls on remittances.

Each of the flows in Eq. (9.1) is discounted to the present. The appropriate discount rate should reflect the uncertainty associated with the flow. CFt is not known with certainty and could fluctuate over the life of the project. Furthermore the nominal cash flows from operations will change over time as inflation changes. The discount rate, d, could be equal to the risk-free rate plus a risk premium that reflects the systematic risk of the project. The financial terms in FINt are likely to be fixed in nominal terms over time. In this case current market interest rates may be acceptable as discount rates, df.

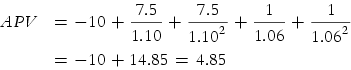

Consider this example to illustrate the APV approach to capital budgeting decisions. Suppose Midas Gold Extractors has an opportunity to enter a small, developing country and apply its new gold recovery technique to some old mines that no longer yield profitable amounts of ore under conventional mining. Midas estimates that the cost of establishing the foreign operation will be $10 million. The project is expected to last for 2 years, during which period the operating cash flows from the new gold extracted will be $7.5 million/year. In addition, the new operating unit will allow Midas to repatriate an additional $1 million/year in funds that have been tied up in the developing country by capital controls. If Midas applies a discount rate of 10% to operating cash flows and 6% to the funds that will be freed from controls, then the APV is:

So the adjusted present value of the gold recovery project equals $4.85 million. The firm can compare this value to the APV of other projects it is considering in order to budget its capital expenditures in the optimum manner.

Capital budgeting is an imprecise science, and forecasting future cash flows is sometimes viewed as more art than science. The typical firm experiments with several alternative scenarios to test the sensitivity of the budgeting decision to different assumptions. One of the key assumptions in projects considered for unstable countries is the level of political risk that must be accounted for. Cash flows should be adjusted for the threat of loss resulting from government expropriation or regulation.

Summary

1. Financial control is necessary in order to monitor the multinational firm’s operations.

2. The firm’s management style determines whether to decentralize or centralize its financial management between the parent and the foreign subsidiaries.

3. Multinational cash management involves managing the firm’s liquid assets (in domestic and foreign currencies) as efficiently as possible.

4. Cash management is centralized management, which allows the parent firm to offset subsidiary payables and receivables such that the overall cash needs for the firm are low.

5. Netting is the consolidation of payables and receivables in a currency so that only the difference between them must be bought or sold.

6. A LOC is a contract written by a bank to guarantee that the bank will pay the exporter the amount of money owed by the importer.

7. The LOC stipulates that payment will be made only upon presentation of required documents by the exporter to the bank. Once the exporter fulfills all obligations, the payment will be made with the bank collecting from the importer to pay the exporter. Failure to pay by the importer will not affect the exporter’s receivable.

8. A bill of lading is a record of the shipper’s receipt and the shipment of goods.

9. A bankers’ acceptance is a draft drawn on a firm and accepted by banks as payable at maturity.

10. A transfer price is the price that one subsidiary charges another subsidiary of internal good transfers.

11. Transfer prices may be used by the multinational firms to minimize taxes on profits from subsidiaries in high-tax countries and shift profits to subsidiaries in low-tax countries.

12. Capital budgeting is a process by which the firm decides which long-term investments to make. It involves the calculation of each project’s future cash flow by period, the present value of the cash flows after considering the time value of money, the number of years it takes for a project’s cash flow to pay back the initial cash investment, an assessment of risk, and other factors.

13. The adjusted present value is the sum of the project’s initial investment cost, the present values of cash flows, and all financial effects related to the investment.

Exercises

1. Suppose that the Japanese firm Sanpo will receive $1.5 million from its US sales subsidiary on June 3. Moreover, on June 3 a US bank is due $2.3 million from Sanpo as repayment of a loan. Explain how netting by Sanpo would apply to this example, and what the advantages are?

2. What could be done if Question 1 is modified so that Sanpo owes the $2.3 million on June 13, but the $1.5 million receivable is still scheduled for June 3?

3. Give an example of how transfer pricing can be used to

a. shift profits to a low-tax subsidiary in Ireland?

b. reduce the tariff on a shipment of computer parts from a subsidiary in Taiwan to a subsidiary in Brazil?

c. increase profits in a French subsidiary that will soon be applying for a loan?

4. What is arm’s-length pricing?

5. Suppose a US multinational firm estimates that a $150 million capital expenditure in a new plant in an unstable developing country will have a life of 2 years before it is confiscated by the foreign government. During this 2-year period, the operating cash flows will be $100 million each year. In addition, the firm will be able to use the new facility to repatriate $10 million each year in funds that have been held in the country involuntarily. If the discount rate for the operations cash flows is 10% and the discount rate for the exchange control avoidance is 8%, what is the adjusted present value of the project?

Appendix A Present Value

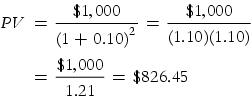

What would you pay today to receive $1000 in 1 year? The answer will vary from individual to individual, but we would all want to pay less than $1000 today. How much less depends on the discount rate—a measure, like an interest rate or rate of return, that we would use to discount to the present the $1000 to be received in 1 year.

Suppose that I require a 10`% return on all my investments. Then one way of viewing present value is as the principal amount today that when invested at 10% simple interest would be worth $1000 when the principal and interest are summed after 1 year. To find the required principal amount, we divide the future value (FV) of $1000 by 1 plus the discount rate (d) of 10%, or the present value (PV) formula, which is

(9A.1)

I would pay $909.09 for the right to receive $1000 in 1 year. Another way of stating this is to say that the present value of $1000 to be received in 1 year is $909.09.

For amounts to be received at some year n in the future, the formula is modified to

(9A.2)

In the example just used, the $1000 is received in 1 year, so n equals 1. What if the $1000 is to be received in 2 years? Then the formula gives us

(9A.3)

(9A.3)

(9A.3)The present value of $1000 to be received in 2 years is $826.45. The farther into the future we go, the lower the present value of any future value. Furthermore the higher the discount rate, the lower the present value of any future value to be received.

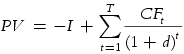

If a capital outlay will generate a stream of earnings to be received over many years, we simply sum the present value of each individual year to obtain the present value of the future cash flows associated with the expenditure. Then we subtract the initial investment or cash outflow to find the present value of the project. If Σ is the summation operator and t denotes time (like years), then the present value of an investment of I dollars today yielding cash flows of CFt over each year t in the future for T years is

(9A.4)

(9A.4)

(9A.4)If we can estimate the after-tax cash flows (CFt) associated with a capital expenditure (I) today, and we can choose an appropriate discount rate (d), then the present value of the project is indicated by Eq. (9A.4).