International Monetary Arrangements

Abstract

International monetary relations are subject to frequent change, with fixed exchange rates, floating exchange rates, and commodity-backed currency all having their advocates. This chapter considers the merits of various alternative international monetary systems, and also provides an interesting and useful historical background of the international monetary system, beginning with the late 19th century when the gold standard began and continuing to present-day systems. International reserve currencies are discussed in detail, with emphasis on the types of foreign exchange arrangements. Major topics covered include currency boards, “dollarization,” choices of exchange rate systems, optimum currency areas, the European Monetary System, and the emergence of the euro.

Keywords

Bretton Woods agreement; closed economy; commodity-backed currency; currency board; dollarization; exchange rate; fixed exchange rate; floating exchange rate; gold standard; International Monetary Fund (IMF); international reserve currencies; optimum currency area; pegged exchange rate; seigniorage

Like most areas of public policy, international monetary relations are subject to frequent proposals for change. Fixed exchange rates, floating exchange rates, and commodity-backed currency all have their advocates. Before considering the merits of alternative international monetary systems, we should understand the background of the international monetary system. Although an international monetary system has existed since monies have been traded, it is common for most modern discussions of international monetary history to start in the late 19th century. It was during this period that the gold standard began.

The Gold Standard: 1880–1914

Although an exact date for the beginning of the gold standard cannot be pinpointed, we know that it started during the period from 1880 to 1890. Under a gold standard, currencies are valued in terms of their gold equivalent (an ounce of gold was worth $20.67 in terms of the US dollar over the gold standard period). The gold standard is an important beginning for a discussion of international monetary systems because when each currency is defined in terms of its gold value, all currencies are linked in a system of fixed exchange rates. For instance, if currency A is worth 0.10 ounce of gold, whereas currency B is worth 0.20 ounce of gold, then 1 unit of currency B is worth twice as much as 1 unit of A, and thus the exchange rate of 1 currency B = 2 currency A is established.

Maintaining a gold standard requires a commitment from participating countries to be willing to buy and sell gold to anyone at the fixed price. To maintain a price of $20.67 per ounce, the United States had to buy and sell gold at that price. Gold was used as the monetary standard because it is a homogeneous commodity (could you have a fish standard?) worldwide that is easily storable, portable, and divisible into standardized units like ounces. Since gold is costly to produce, it possesses another important attribute—governments cannot easily increase its supply. A gold standard is a commodity money standard. Money has a value that is fixed in terms of the commodity gold.

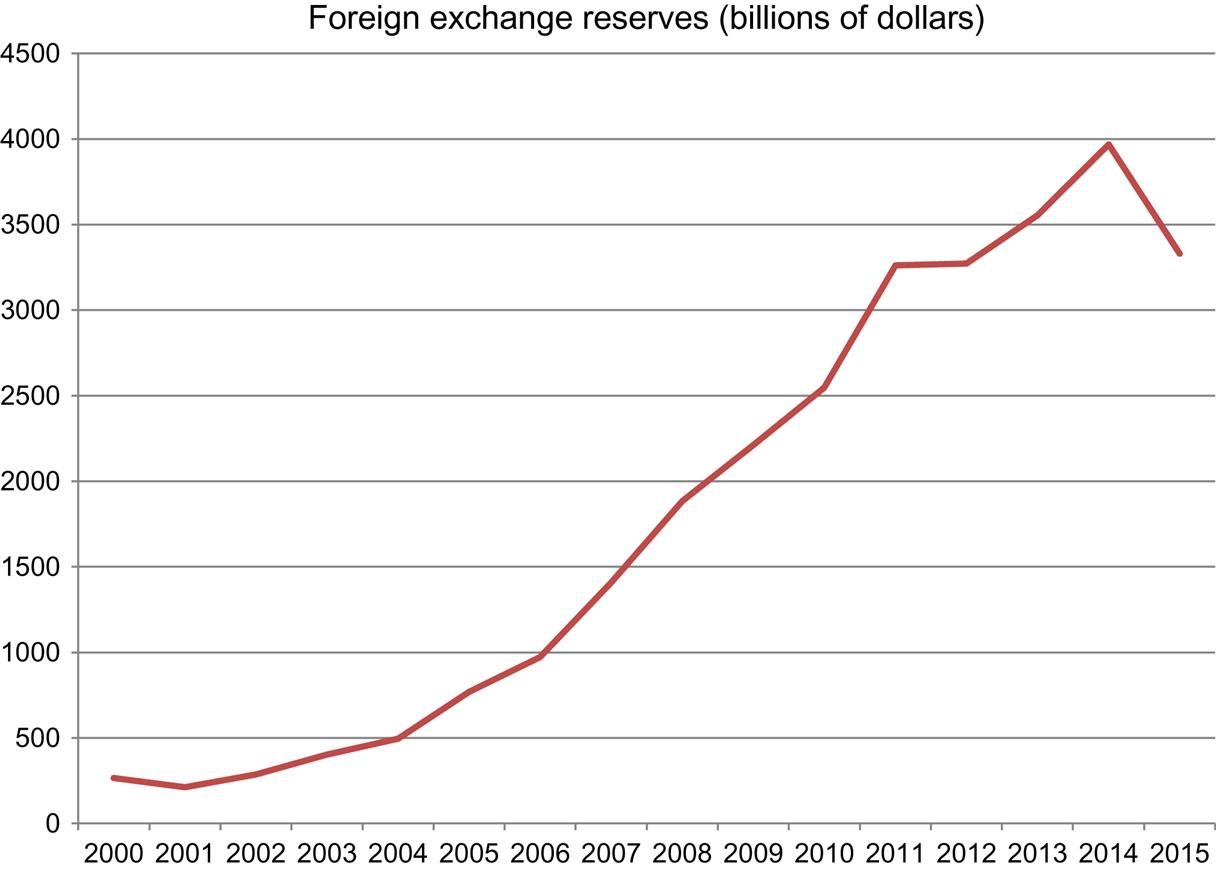

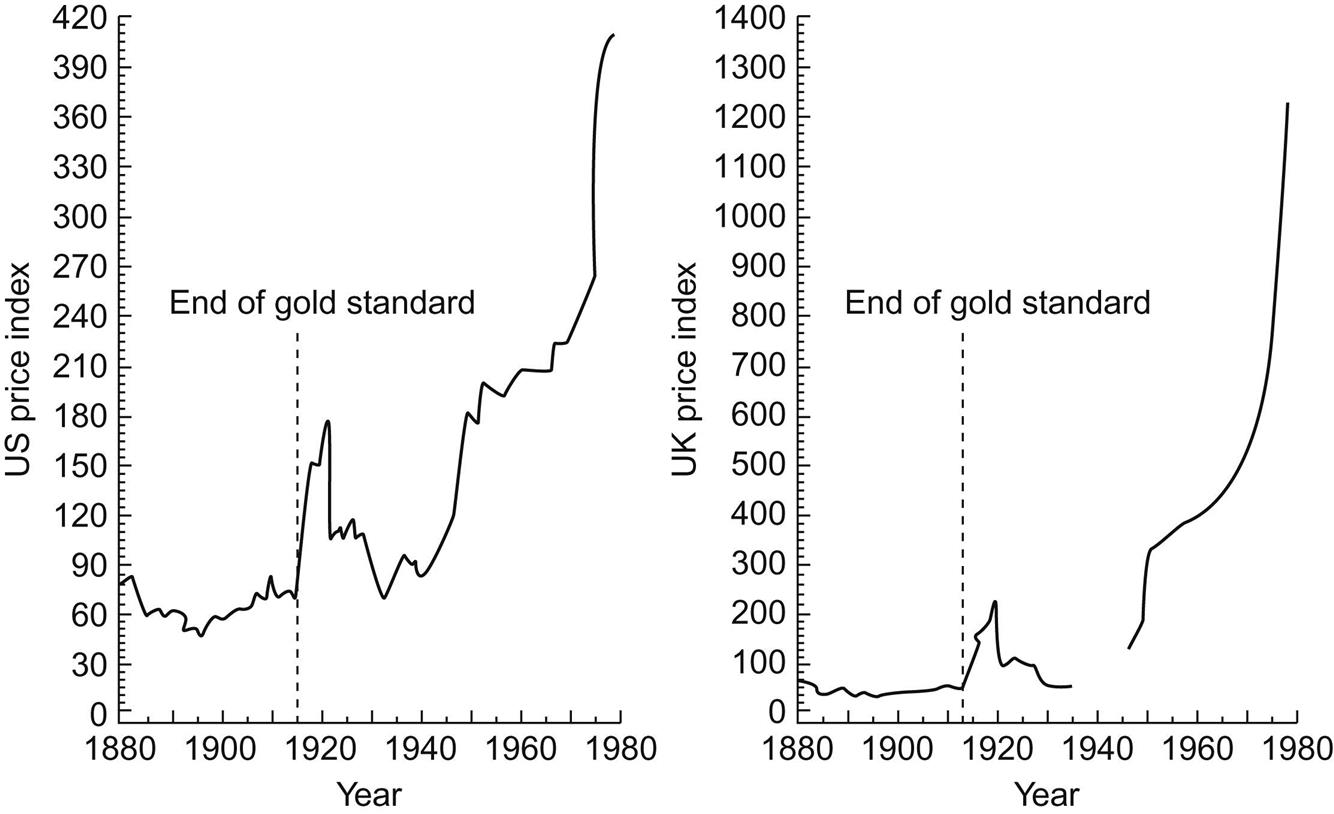

One aspect of a money standard that is based on a commodity with relatively fixed supply is long-run price stability. Since governments must maintain a fixed value of their money relative to gold, the supply of money is restricted by the supply of gold. Prices may still rise and fall with swings in gold output and economic growth, but the tendency is to return to a long-run stable level. Fig. 2.1 illustrates graphically the relative stability of US and UK prices over the gold standard period as compared to later years. However, note also that prices fluctuated up and down in the short run during the gold standard. Thus, frequent small bursts of inflation and deflation occurred in the short run, but in the long run the price level remained unaffected. Since currencies were convertible into gold, national money supplies were constrained by the growth of the stock of gold. As long as the gold stock grew at a steady rate, prices would also follow a steady path. New discoveries of gold would generate discontinuous jumps in the price level, but the period of the gold standard was marked by a fairly stable stock of gold.

People today often look back on the gold standard as a “golden era” of economic progress. It is common to hear arguments supporting a return to the gold standard. Such arguments usually cite the stable prices, economic growth, and development of world trade during this period as evidence of the benefits provided by such an orderly international monetary system. Others have suggested that the economic development and stability of the world economy in those years did not necessarily reflect the existence of the gold standard but, instead, the absence of any significant real shocks such as war. Although we may disagree on the merits of returning to a gold standard, it seems fair to say that the development of world trade was encouraged by the systematic linking of national currencies and the price stability of the system. Since gold is like a world money during a gold standard, we can easily understand how a balance of payments disequilibrium may be remedied. A country running a balance of payments (official settlements) deficit would find itself with net outflows of gold, which would reduce its money supply and, in turn, its prices. A surplus country would find gold flowing in and expanding its money supply, so that prices rose. The fall in price in the deficit country would lead to greater net exports (exports minus imports), and the rise in price in the surplus country would reduce its net exports, so that balance of payments equilibrium would be restored.

In practice, actual flows of gold were not the only, or even necessarily the most important, means of settling international debts during this period. Since London was the financial center of the world, and England the world’s leading trader and source of financial capital, the pound also served as a world money. International trade was commonly priced in pounds, and trade that never passed through England was often paid for with pounds.

The Interwar Period: 1918–1939

World War I ended the gold standard. International financial relations are greatly strained by war, because merchants and bankers must be concerned about the probability of countries suspending international capital flows. At the beginning of the war both the patriotic response of each nation’s citizens and legal restrictions stopped private gold flows. Since wartime financing required the hostile nations to manage international reserves very carefully, private gold exports were considered unpatriotic. Central governments encouraged (and sometimes mandated) that private holders of gold and foreign exchange sell these holdings to the government.

Because much of Europe experienced rapid inflation during the war and in the period immediately following it, it was not possible to restore the gold standard at the old exchange values. However, the United States had experienced little inflation and thus returned to a gold standard by June 1919. The war ended Britain’s financial preeminence, since the United States had risen to the status of the world’s dominant banker country. In the immediate postwar years the pound fluctuated freely against the dollar in line with changes in the price level of each country.

In 1925, England returned to a gold standard at the old prewar pound per gold exchange rate, even though prices had risen since the prewar period. As John Maynard Keynes had correctly warned, the overvalued pound hurt UK exports and led to a deflation of British wages and prices. By 1931, the pound was declared inconvertible because of a run on British gold reserves (a large demand to convert pounds into gold), and so ended the brief UK return to a gold standard. Once the pound was no longer convertible into gold, attention centered on the US dollar. A run on US gold at the end of 1931 led to a 15% drop in US gold holdings. Although this did not lead to an immediate change in US policy, by 1933 the United States abandoned the gold standard.

The depression years were characterized by international monetary warfare. In trying to stimulate domestic economies by increasing exports, country after country devalued, so that the early to mid-1930s may be characterized as a period of competitive devaluations. Governments also resorted to foreign exchange controls in an attempt to manipulate net exports in a manner that would increase gross domestic product (GDP). Of course, with the onslaught of World War II, the hostile countries utilized foreign exchange controls to aid the war-financing effort.

The Bretton Woods Agreement: 1944–1973

Memories of the economic warfare of the interwar years led to an international conference at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944. At the close of World War II there was a desire to reform the international monetary system to one based on mutual cooperation and freely convertible currencies.

There was a need for a system that fixed currencies relative to each other, but did not fix each currency in terms of gold. The Bretton Woods agreement solved this problem by requiring that each country fix the value of its currency in terms of an anchor currency, namely the dollar (this established the “par” value of each currency and was to ensure parity across currencies). The US dollar was the key currency in the system, and $1 was defined as being equal in value to 1/35 ounce of gold. Since every currency had an implicitly defined gold value, through the link to the dollar, all currencies were linked in a system of fixed exchange rates.

Nations were committed to maintaining the parity value of their currencies within 1% of parity. The various central banks were to achieve this goal by buying and selling their currencies (usually against the dollar) on the foreign exchange market. When a country was experiencing difficulty maintaining its parity value because of balance of payments disequilibrium, it could turn to a new institution created at the Bretton Woods Conference: the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF was created to monitor the operation of the system and provide short-term loans to countries experiencing temporary balance of payments difficulties. Such loans are subject to IMF conditions regarding changes in domestic economic policy aimed at restoring balance of payments equilibrium.

In the case of a fundamental disequilibrium, when the balance of payments problems are not of a temporary nature, a country could apply for permission from the IMF to devalue or revalue its currency. Such a permanent change in the parity rate of exchange was rare. Table 2.1 summarizes the history of exchange rate adjustments over the Bretton Woods period for the major industrial countries. The Bretton Woods system, although essentially a fixed, or pegged, exchange rate system, allowed for changes in exchange rates when economic circumstances warranted such changes. In actuality, the system is best described as an adjustable peg. The system may also be described as a gold exchange standard because the key currency, the dollar, was convertible into gold for official holders of dollars (such as central banks and treasuries).

Table 2.1

Exchange rates of the major industrial countries over the period of the Bretton woods agreement

| Country | Exchange ratesa |

| Canada | Floated until May 2, 1962, then pegged at C$1.081 = $1. Floated again on June 1, 1970. |

| France | No official IMF parity value after 1948 (although the actual rate hovered around FF350 = $1) until December 29, 1958, when rate fixed at FF493.7 = $1 (old francs). One year later, rate was FF4.937 = $1 when new franc (one new franc was equal to 100 old francs) was created. Devaluation to FF5.554 = $1 on August 10, 1969. |

| Germany | Revalued on March 6, 1961, from DM4.20 = $1 to DM4.0 = $1. Revalued to DM3.66 = $1 on October 26, 1969. |

| Italy | Pegged at Lit625 = $1 from March 30, 1960, until August 1971. |

| Japan | Pegged at ¥360 = $1 until 1971. |

| Netherlands | Pegged at F13.80 = $1 until March 7, 1961, when revalued at F13.62 = $1. |

| United Kingdom | Devalued from $2.80 = £1 to $2.40 = £1 on November 11, 1967. |

aRelative to the US dollar.

Central Bank Intervention During Bretton Woods

By signing the Bretton Woods agreement, countries agreed to protect their exchange rate from moving up or down from the agreed-upon rate. This agreement implied that central banks had to take on a more active role in making sure that market pressure did not change the exchange rate. The various central banks achieved this goal by buying and selling their domestic currencies on the foreign exchange market. The central bank intervention can be illustrated using the trade flow model developed in Chapter 1, The Foreign Exchange Market. Assume that the United States and the United Kingdom are trading with each other, and that the UK residents start demanding more Fords (a US good). In the first chapter you learned that this would imply a shift in the supply curve for pounds. UK traders would be more willing to supply their pounds to banks in exchange for dollars, because the traders want to buy US goods. Banks see more customers supplying pounds and demanding dollars, causing banks to want to depreciate the pound. Fig. 2.2 illustrates the shift in the supply curve causing the banks to want to depreciate the pound from a starting dollar/pound exchange rate of 2.00 to a new equilibrium exchange rate of 1.80.

To prevent the pound from depreciating the Bank of England (the central bank in the United Kingdom) has to intervene in the foreign exchange market. The Bank of England must intervene by buying up pounds and selling dollars that they have already stored in their bank vaults. Fig. 2.2 shows that the Bank of England has to buy a quantity of pounds equivalent to the distance from Q1 to Q3, and sell a quantity of dollars equal to the quantity of pounds multiplied by the 2.00 exchange rate. This action would supply enough dollars to prevent private banks and traders from changing the exchange rate.

Note that the model used to illustrate the intervention is a flow model. This means that in each period the situation will occur. For example, if the period is a year, then the excess supply of pounds will exist every year, as long as the new demand for Fords exists. Thus, the Bank of England has to intervene each year and buy pounds and sell dollars. If the excess supply persists too long, the Bank of England may run out of dollars in their vaults, and would be forced to apply for permission from the IMF to devalue their currency to be in line with the new market exchange rate (in this example 1.80).

The Breakdown of the Bretton Woods System

The Bretton Woods system worked well through the 1950s and part of the 1960s. In 1960, there was a dollar crisis because the United States had run large balance of payments deficits in the late 1950s. Concern over large foreign holdings of dollars led to an increased demand for gold. Central bank cooperation in an international gold pool managed to stabilize gold prices at the official rate, but still the pressures mounted. Although the problem of chronic US deficits and Japanese and European surpluses could have been remedied by revaluing the undervalued yen, mark, and franc, the surplus countries argued that it was the responsibility of the United States to restore balance of payments equilibrium.

The failure to realign currency values in the face of fundamental economic change spelled the beginning of the end for the gold exchange standard of the Bretton Woods agreement. By the late 1960s the foreign dollar liabilities of the United States were much larger than the US gold stock. The pressures of this “dollar glut” finally culminated in August 1971, when President Nixon declared the dollar to be inconvertible and provided a close to the Bretton Woods era of fixed exchange rates and convertible currencies.

The Transition Years: 1971–1973

In December 1971, an international monetary conference was held to realign the foreign exchange values of the major currencies. The Smithsonian agreement provided for a change in the dollar per gold exchange value from $35 to $38.02 per ounce of gold. At the same time that the dollar was being devalued by about 8%, the surplus countries saw their currencies revalued upward. After the change in official currency values the system was to operate with fixed exchange rates under which the central banks would buy and sell their currencies to maintain the exchange rate within 2.25% of the stated parity. Although the realignment of currency values provided by the Smithsonian agreement allowed a temporary respite from foreign exchange crises, the calm was short-lived. Speculative flows of capital began to put downward pressure on the pound and lira. In June 1972, the pound began to float according to supply and demand conditions. The countries experiencing large inflows of speculative capital, such as Germany and Switzerland, applied legal controls to slow further movements of money into their countries.

Although the gold value of the dollar had been officially changed, the dollar was still inconvertible into gold, and thus the major significance of the dollar devaluation was with respect to the foreign exchange value of the dollar, not to official gold movements. The speculative capital flows of 1972 and early 1973 led to a further devaluation of the dollar in February 1973, when the official price of an ounce of gold rose from $38 to $42.22. Still, the speculative capital flows persisted from the weak to the strong currencies. Finally, in March 1973, the major currencies began to float.

International Reserve Currencies

International reserves are the means of settling international debts. Under the gold standard, gold was the major component of international reserves. Following World War II, we had a gold exchange standard in which international reserves included both gold and a reserve currency, the US dollar. The reserve currency country was to hold gold as backing for the outstanding balances of the currency held by foreigners. These foreign holders of the currency were then free to convert the currency into gold if they wished. However, as we observed with the dollar, once the convertibility of the currency becomes suspect, or once large amounts of the currency are presented for gold, the system tends to fall apart.

At the end of World War II, and throughout the 1950s, the world demanded dollars for use as an international reserve. During this time, US balance of payments deficits provided the world with a much-needed source of growth for international reserves. As the rest of the world developed and matured, over time US liabilities to foreigners greatly exceeded the gold reserve backing these liabilities. Yet as long as the increase in demand for these dollar reserves equaled the supply, the lack of gold backing was irrelevant. Through the late 1960s, US political and economic events began to cause problems for the dollar’s international standing, and the continuing US deficits were not matched by a growing demand, so that pressure to convert dollars into gold resulted in the dollar being declared officially no longer exchangeable for gold in August 1971.

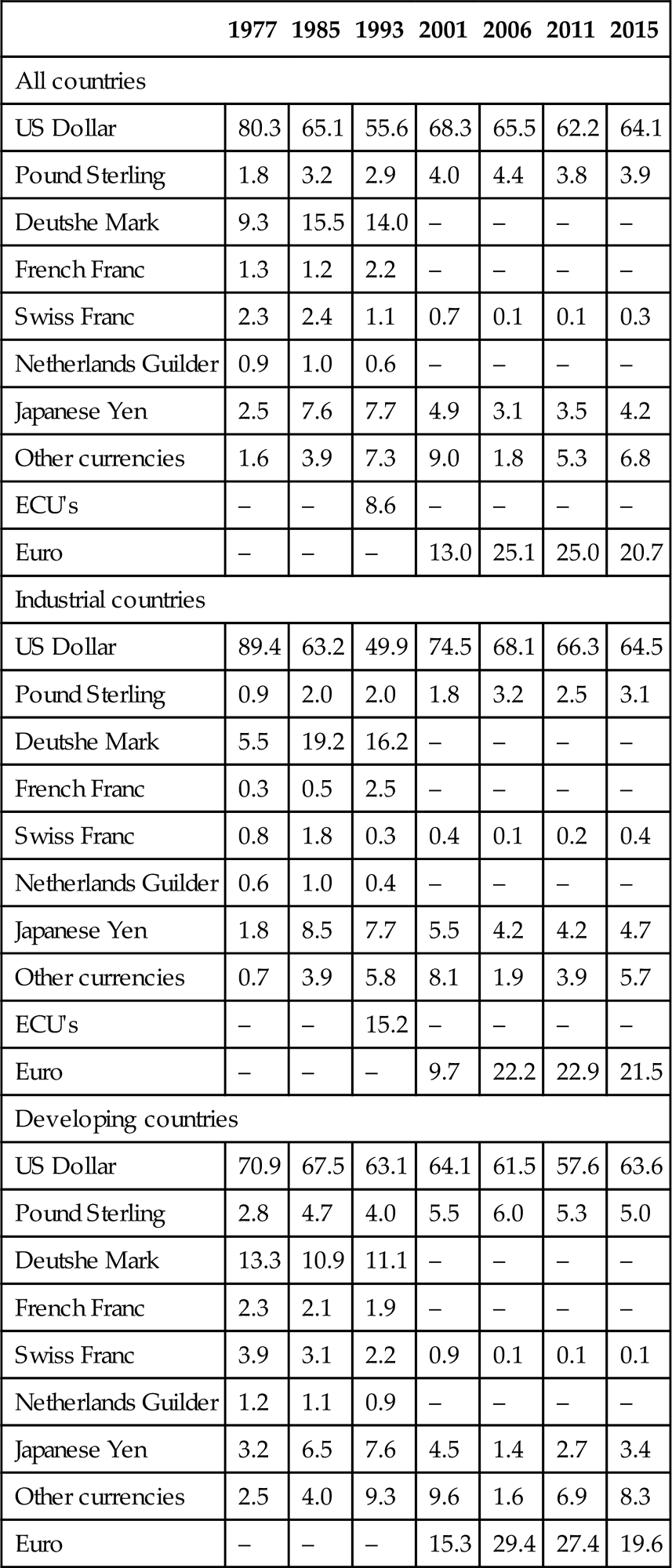

Table 2.2 illustrates the diversification of the currency composition of foreign exchange reserves since the mid-1970s. The table shows a falling share of international reserves devoted to dollars until the beginning of the 1990s. The mark and yen gained larger shares of the international reserve portfolio from the mid-1970s to mid-1990s. In the 2000s the dollar share once again increased. Although the share of the dollar in 2015 is not as high as in the mid-1970s, it still exceeds 60% of the international reserves. Furthermore, the euro has a substantial share of reserves, at 20.7%, but it has not threatened the dominance of the dollar.

Table 2.2

Share of national currencies in total identified official holdings of foreign exchange (in %)

| 1977 | 1985 | 1993 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | 2015 | |

| All countries | |||||||

| US Dollar | 80.3 | 65.1 | 55.6 | 68.3 | 65.5 | 62.2 | 64.1 |

| Pound Sterling | 1.8 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| Deutshe Mark | 9.3 | 15.5 | 14.0 | – | – | – | – |

| French Franc | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.2 | – | – | – | – |

| Swiss Franc | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Netherlands Guilder | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 | – | – | – | – |

| Japanese Yen | 2.5 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 4.9 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4.2 |

| Other currencies | 1.6 | 3.9 | 7.3 | 9.0 | 1.8 | 5.3 | 6.8 |

| ECU's | – | – | 8.6 | – | – | – | – |

| Euro | – | – | – | 13.0 | 25.1 | 25.0 | 20.7 |

| Industrial countries | |||||||

| US Dollar | 89.4 | 63.2 | 49.9 | 74.5 | 68.1 | 66.3 | 64.5 |

| Pound Sterling | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Deutshe Mark | 5.5 | 19.2 | 16.2 | – | – | – | – |

| French Franc | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.5 | – | – | – | – |

| Swiss Franc | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Netherlands Guilder | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | – | – | – | – |

| Japanese Yen | 1.8 | 8.5 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.7 |

| Other currencies | 0.7 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 8.1 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 5.7 |

| ECU's | – | – | 15.2 | – | – | – | – |

| Euro | – | – | – | 9.7 | 22.2 | 22.9 | 21.5 |

| Developing countries | |||||||

| US Dollar | 70.9 | 67.5 | 63.1 | 64.1 | 61.5 | 57.6 | 63.6 |

| Pound Sterling | 2.8 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.0 |

| Deutshe Mark | 13.3 | 10.9 | 11.1 | – | – | – | – |

| French Franc | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.9 | – | – | – | – |

| Swiss Franc | 3.9 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Netherlands Guilder | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | – | – | – | – |

| Japanese Yen | 3.2 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 3.4 |

| Other currencies | 2.5 | 4.0 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 1.6 | 6.9 | 8.3 |

| Euro | – | – | – | 15.3 | 29.4 | 27.4 | 19.6 |

Source: IMF, Currency Compilation of Official Foreign Reserves (COFER), September, 2015; Data for 2015 is first quarter data.

At first glance, it may appear very desirable to be the reserve currency and have other countries accept your balance of payments deficits as a necessary means of financing world trade. The difference between the cost of creating new balances and the real resources acquired with the new balances is called seigniorage. Seigniorage is a financial reward accruing to the issuer of currency. The central bank’s seigniorage is the difference between the cost of money creation and the return to the assets it acquires. In addition to such central bank seigniorage, a reserve currency country also receives additional seigniorage when foreign countries demand the currency issued and put those in its vaults, as this reduces the inflationary pressure that money creation causes.

Table 2.2 indicates that the dollar is still, by far, the dominant reserve currency. Since the US international position has been somewhat eroded in the past few decades, the question arises as to why we did not see the Japanese yen, or Swiss franc emerge as the dominant reserve currency. Although the yen and Swiss franc have been popular currencies, the respective governments in each country have resisted a greater international role for their monies. Besides the apparently low additional seigniorage return to the dominant international money, there is another reason for these countries to resist. The dominant money producer (country) finds that international shifts in the demand for its money may have repercussions on domestic operations. For a country the size of the United States, domestic economic activity is large relative to international activity, so international capital flows of any given magnitude have a much smaller potential to disrupt US markets than would be the case for Japanese, or Swiss markets, where foreign operations are much more important. In this sense, it is clear why these countries have withstood the movement of the yen and franc to reserve currency status. Over time, we may find that the euro emerges as a dominant reserve currency as the combined economies of the euro-area countries provide a very large base of economic activity. However, Table 2.2 shows that the euro still only accounts for 20.7% of total international reserves, so it is not close to the 64.1% share taken by the dollar. In addition, the euro share seems to have stabilized at around 21–22% of the reserve holdings. Most of the growth in the euro reserve holdings has come at the expense of other currencies than the dollar, effectively creating a dual currency reserve system with the dollar and the euro dominating the international reserves.

In domestic monetary theory, economists often identify three roles of money. Money is said to serve as (1) a unit of account, (2) a medium of exchange, and (3) a store of value. Likewise, in an international context we can explain the choice of a reserve currency according to criteria relevant for each role. Table 2.3 summarizes the roles of a reserve currency. First, the role of the international unit of account results from information costs. We find that primary goods like coffee, tin, or rubber are quoted in terms of dollars worldwide. Since these goods are homogeneous, at least relative to manufactured goods, information regarding their value is conveyed more quickly when prices are quoted in terms of one currency worldwide. The private use as an invoicing currency in international trade contracts arises from the reserve currency’s informational advantage over other currencies. Besides being a unit of account for private contracts, the reserve currency also serves as a base currency to which other currencies peg exchange rates.

Table 2.3

| Function | Resulting from private role | Official role | |

| 1. International unit of account | Information costs | Invoicing currency | Pegging currency |

| 2. International medium of exchange | Transaction costs | Vehicle currency | Intervention currency |

| 3. International store of value | Stable value | Banking currency | Reserve currency |

A currency’s role as an international medium of exchange is the result of transaction costs. In the case of the US dollar, the dollar is so widely traded that it is often cheaper to go from currency A to dollars to currency B, than directly from currency A to currency B. Thus, it is efficient to use the dollar as an international medium of exchange, and the dollar serves as the vehicle for buying and selling nondollar currencies. The private (mainly interbank) role as a vehicle currency means that the dollar (or the dominant reserve currency) will also be used by central banks in foreign exchange market intervention aimed at achieving target levels for exchange rates.

Finally, a currency’s role as an international store of value results from the stability of its value. In other words, certainty of future value enhances a currency’s role as a store of purchasing power. The US dollar’s role in this area was diminished in the 1970s, and it seems likely that further instability in US monetary policy would contribute to a further fall. The private market use of the dollar for denominating international loans and deposits indicates the role of the dominant reserve currency in banking. In addition, countries will choose to hold their official reserves largely in the dominant reserve currency.

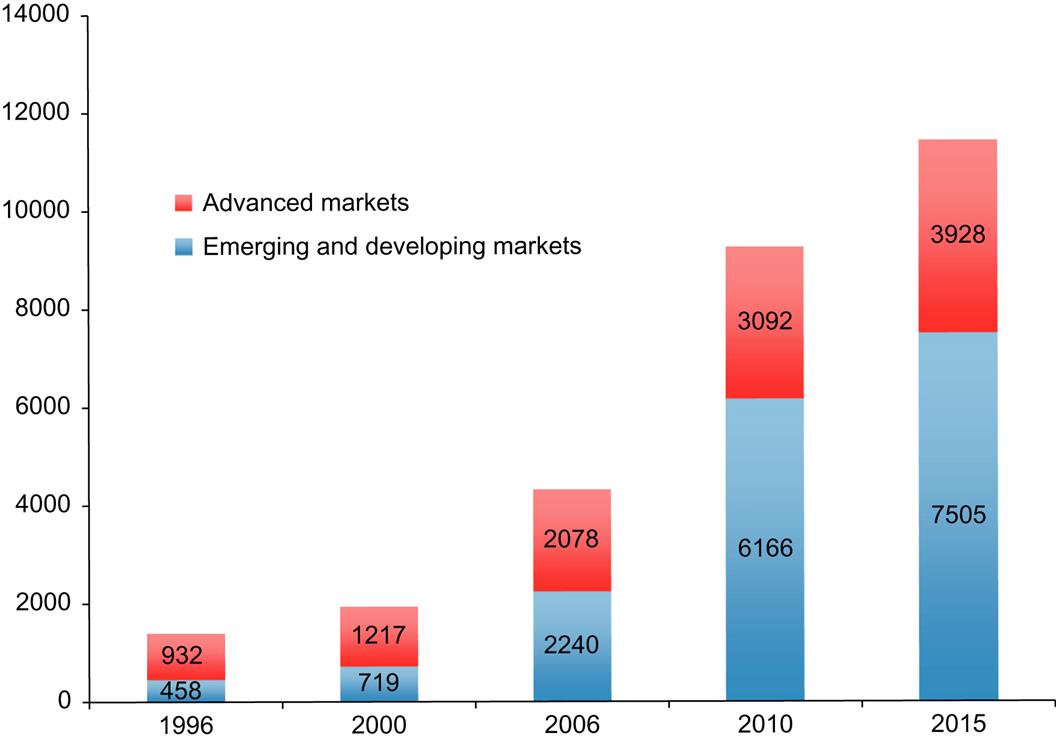

Fig. 2.3 shows the sharp growth in foreign reserves that has occurred in the last decade. During the Bretton Woods period the size of the foreign reserves was a topic of interest, but became less important in the 1970s and 1980s. This topic has rebounded again as foreign reserve holdings have grown enormously in the 2000s. In particular emerging economies, dominated by China, have added tremendous amounts of foreign exchange reserves. This sharp growth has been accompanied by sharp imbalances in trade balances, which will be a topic in the next chapter. However, before we can address the question of trade imbalances, we need to explore how exchange rate systems changed once the Bretton Woods agreement collapsed.

Post Bretton Woods: 1973 to the Present

Although we refer to the exchange rate system in existence since 1973 as a floating rate system, few countries completely allow the market to define the exchange rate. In such a case we would call the exchange rate system a “purely floating” one. Instead, a multitude of methods to partly or completely control the exchange rate has emerged. This choice of exchange rate system also dictates limitations on the ability of the central bank to conduct its monetary policy. Fig. 2.4 illustrates the major categories of exchange rate arrangements and the effect that such arrangements have on the monetary policy independence of a country. The types of exchange rate systems, in Fig. 2.4, range from (1), “dollarization” where the central bank of the country has completely given up control of the money supply to adopt some other country’s currency, to the other extreme of (6), purely floating, where the central bank retains domestic control over the currency in the country. In between, the central bank has some degree of control over the money supply.

The above categories can be summarized under three headings: peg, mixed, and floating, as shown in Fig. 2.5. All pegs involve a fixed rate that is selected by the government, whereas all the floating rates are to some degree market determined. The target bands and crawling pegs are exchange rate systems, somewhere in between the peg and floating, sharing some features of each. For example the target bands allow the exchange rate to be market determined within some range, but the rate is not allowed to go outside a range that is predetermined by the government.

We provide a brief description of each of the types of foreign exchange arrangements, starting with the exchange rate system with the most independent monetary policy to the one with the least independent monetary policy:

Free floating—The exchange rate is market determined, and any intervention is aimed at moderating fluctuations rather than determining the level of the exchange rate.

Managed floating—The monetary authority (usually the central bank) influences the exchange rate periodically through active foreign exchange market intervention with no preannounced path for the exchange rate.

Horizontal bands or Target Bands—The exchange rate fluctuates within an upper and lower band around a fixed central target rate. Such target bands allow for a moderate amount of exchange rate fluctuation while tying the currency to the target central rate.

Crawling pegs—The exchange rate is adjusted periodically in small amounts at a fixed, preannounced rate or in response to certain indicators (such as inflation differentials against major trading partners).

Crawling bands—The exchange rate is maintained within certain fluctuation margins around a central rate that is periodically adjusted at a fixed, preannounced rate or in response to certain indicators.

Fixed peg or Conventional Peg—The exchange rate is fixed against a major currency or some basket of currencies. Active intervention may be required to maintain the target pegged rate.

Currency board—A fixed exchange rate is established by a legislative commitment to exchange domestic currency for a specified foreign currency at a fixed exchange rate. New issues of domestic currency are typically backed in some fixed ratio (like one-to-one) by additional holdings of the key foreign currency.

“Dollarization” or No separate legal tender—Another country’s currency is unilaterally adopted as the legal tender.

In Appendix A specific country examples of each of the above currency arrangements are provided.

The Choice of an Exchange Rate System

Perfectly fixed or pegged exchange rates would work much as a gold standard does. All currencies would fix their exchange rate in terms of another currency, say, the dollar, and thereby would fix their rate relative to every other currency. Under such an arrangement each country would have to follow the monetary policy of the key currency in order to experience the same inflation rate and keep the exchange rate fixed.

Flexible or floating exchange rates occur when the exchange rate is determined by the market forces of supply and demand. As the demand for a currency increases relative to supply, that currency will appreciate, whereas currencies in which the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded will depreciate.

Economists do not all agree on the advantages and disadvantages of a floating as opposed to a pegged exchange rate system. For instance, some would argue that a major advantage of flexible rates is that each country can follow domestic macroeconomic policies independent of the policies of other countries. To maintain fixed exchange rates, countries have to share a common inflation experience, which was often a source of problems under the post–World War II system of fixed exchange rates. If the dollar, which was the key currency for the system, was inflating at a rate faster than, say, Japan desired, then the lower inflation rate followed by the Japanese led to pressure for an appreciation of the yen relative to the dollar. Thus the existing pegged rate could not be maintained. Yet with flexible rates, each country can choose a desired rate of inflation and the exchange rate will adjust accordingly. Thus, if the United States chooses 8% inflation and Japan chooses 3%, there will be a steady depreciation of the dollar relative to the yen (absent any relative price movements). Given the different political environment and cultural heritage existing in each country, it is reasonable to expect different countries to follow different monetary policies. Floating exchange rates allow for an orderly adjustment to these differing inflation rates.

Still there are those economists who argue that the ability of each country to choose an inflation rate is an undesirable aspect of floating exchange rates. These proponents of fixed rates indicate that fixed rates are useful in providing an international discipline on the inflationary policies of countries. Fixed rates provide an anchor for countries with inflationary tendencies. By maintaining a fixed rate of exchange to the dollar (or some other currency), each country’s inflation rate is “anchored” to the dollar, and thus will follow the policy established for the dollar.

Critics of flexible exchange rates have also argued that flexible exchange rates would be subject to destabilizing speculation. By destabilizing speculation we mean that speculators in the foreign exchange market will cause exchange rate fluctuations to be wider than they would be in the absence of such speculation. The logic suggests that, if speculators expect a currency to depreciate, they will take positions in the foreign exchange market that will cause the depreciation as a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. But speculators should lose money when they guess wrong, so that only successful speculators will remain in the market, and the successful players serve a useful role by “evening out” swings in the exchange rate. For instance, if we expect a currency to depreciate or decrease in value next month, we could sell the currency now, which would result in a current depreciation. This will lead to a smaller future depreciation than would occur otherwise. The speculator then spreads the exchange rate change more evenly through time and tends to even out big jumps in the exchange rate. If the speculator had bet on the future depreciation by selling the currency now and the currency appreciates instead of depreciates, then the speculator loses and will eventually be eliminated from the market if such mistakes are repeated.

Research has shown that there are systematic differences between countries choosing to peg their exchange rates and those choosing floating rates. One very important characteristic is country size in terms of economic activity or GDP. Large countries tend to be more independent and less willing to subjugate domestic policies with a view toward maintaining a fixed rate of exchange with foreign currencies. Since foreign trade tends to constitute a smaller fraction of GDP the larger the country is, it is perhaps understandable that larger countries are less attuned to foreign exchange rate concerns than are smaller countries.

The openness of the economy is another important factor. By openness, we mean the degree to which the country depends on international trade. The greater the fraction of tradable (i.e., internationally tradable) goods in GDP, the more open the economy will be. A country with little or no international trade is referred to as a closed economy. As previously mentioned, openness is related to size. The more open the economy, the greater the weight of tradable goods prices in the overall national price level, and therefore the greater the impact of exchange rate changes on the national price level. To minimize such foreign-related shocks to the domestic price level, the more open economy tends to follow a pegged exchange rate.

Countries that choose higher rates of inflation than their trading partners will have difficulty maintaining an exchange rate peg. We find, in fact, that countries whose inflation experiences are different from the average follow floating rates, or a crawling-peg-type system in which the exchange rate is adjusted at short intervals to compensate for the inflation differentials.

Countries that trade largely with a single foreign country tend to peg their exchange rate to that country’s currency. For instance, since the United States accounts for the majority of Barbados trade, by pegging to the US dollar, Barbados imparts to its exports and imports a degree of stability that would otherwise be missing. By maintaining a pegged rate between the Barbados dollar and the US dollar, Barbados is not unlike another state of the United States as far as pricing goods and services in United States–Barbados trade. Countries with diversified trading patterns will not find exchange rate pegging so desirable.

The evidence from previous studies indicates quite convincingly the systematic differences between peggers and floaters, which is summarized in Table 2.4. But there are exceptions to these generalities because neither all peggers nor all floaters have the same characteristics. We can safely say that, in general, the larger the country is, the more likely it is to float its exchange rate; the more closed the economy is, the more likely the country will float; and so on. The point is that economic phenomena, and not just political maneuvering, ultimately influence foreign exchange rate practices.

Table 2.4

Characteristics associated with countries choosing to peg or float

| Peggers | Floaters |

| Small size | Large size |

| Open economy | Closed economy |

| Harmonious inflation rate | Divergent inflation rate |

| Concentrated trade | Diversified trade |

There is also concern about how the choice of an exchange rate system affects the stability of the economy. If the domestic policy authorities seek to minimize unexpected fluctuations in the domestic price level, then they will choose an exchange rate system that best minimizes such fluctuations. For instance, the greater the foreign tradable goods price fluctuations are, the more likely there will be a float, since the floating exchange rate helps to insulate the domestic economy from foreign price disturbances. The greater the domestic money supply fluctuations are, the more likely there will be a peg, since international money flows serve as shock absorbers that reduce the domestic price impact of domestic money supply fluctuations. With a fixed exchange rate, an excess supply of domestic money will cause a capital outflow because some of this excess supply is eliminated via a balance of payments deficit. With floating rates, the excess supply of money is contained at home and reflected in a higher domestic price level and depreciating domestic currency. Once again, the empirical evidence supports the notion that real-world exchange rate practices are determined by such economic phenomena.

Currency Boards and “Dollarization”

Developing countries with a long history of unstable exchange rates often find it difficult to convince the public that government policy will maintain stable exchange rates in the future. This lack of credibility on the part of a government can be overcome if some sort of constraint is placed on the discretionary policy-making ability of the authorities with control over monetary and exchange rate policy. One such form of constraint is a currency board. This form became the prototype for successful exchange rate pegging in the 1990s with the success of Argentina and Hong Kong in maintaining their currency value. However, the failure of the Argentinian currency board in 2001 led to a search for a new way to solve the credibility problem. With both Ecuador and El Salvador becoming “dollarized” to solve the credibility problem, this section also discusses the potential for solving the credibility problem by adopting another currency unilaterally.

The typical demise of a fixed exchange rate system comes when the central bank runs out of foreign currency to exchange for domestic currency and ends up devaluing the domestic currency. Currency boards achieve a credible fixed exchange rate by holding a stock of the foreign currency equal to 100% of the outstanding currency supply of the nation. As a result of such foreign currency holdings, people believe that the board will always have an adequate supply of foreign currency to exchange for domestic currency at the fixed rate of exchange. Critics of currency boards point to such reserve holdings as a cost of operating a currency board. However, since the board holds largely short-term, interest-bearing securities denominated in the foreign currency rather than actual noninterest-bearing currency to back its own currency, these interest earnings tend to make currency boards profitable.

During the Asian financial crisis in 1997–1998, the debate over currency boards was heightened by a proposed currency board for Indonesia. The Indonesian government wanted to introduce a currency board to buy credibility for the rupiah and halt a rapid rupiah depreciation. Critics emphasized several potential problems with a currency board that eventually led to the abandonment of the Indonesian plan. Critics emphasized that a currency board can only succeed if a sustainable fixed rate of exchange between the domestic currency and the US dollar is chosen. An obvious problem is what exchange rate is correct? If the exchange rate overvalues the domestic currency, then the currency board would be “attacked” by speculators exchanging domestic currency for dollars, betting on a devaluation of the domestic currency. Because the currency board has a finite supply of dollars, an exchange rate fixed at unsustainable levels would eventually lead to a large loss of dollar reserves so that the currency board collapses and the exchange rate is eventually devalued. Another problem related to a currency board is that the requirement to maintain foreign currency backing for the domestic currency would constrain the central bank from responding to a domestic financial crisis where the central bank might act as a “lender of last resort” to financial institutions. Because the central bank cannot create domestic currency to lend to domestic institutions facing a “credit crunch,” the financial crisis could potentially erupt into a national economic crisis with a serious recession.

It is important to remember that boards do not engage in the monetary policy actions typical of central banks like the Federal Reserve in the United States. Their sole function is to provide for a fixed exchange rate between the domestic currency and some major currency like the US dollar. To promote public confidence in the banking system, some currency board countries also have central banks that simultaneously provide supervision of the domestic banking system and act as lenders of last resort to troubled banks. However, such central banks have no discretionary authority to influence the exchange rate; if they did, the public would likely doubt the government’s commitment to maintaining the fixed exchange rate.

Appendix A shows that there are a substantial number of countries with currency boards. The ECCU member countries, Djibouti and Hong Kong, use the US dollar as the pegged currency for their currency boards. Some other countries, such as Bosnia-Herzegovina and Bulgaria, have chosen to peg the euro using a currency board. The choice of fixed versus floating exchange rates is often a difficult one for governments. In the case of developing countries that have made a choice for fixed rates, but face a skeptical public due to past policy mistakes, a currency board may be a reasonable way to establish a credible exchange rate system. Hong Kong has had a long successful currency board that even survived the Asian financial crisis. However, the recent experience of Argentina shows that a currency board is no guarantee of success.

For a decade, Argentina maintained a currency board arrangement that supported an exchange rate of 1 peso per US dollar. However, large fiscal deficits resulted in the essential insolvency of the government. At the same time that the government amassed large debts denominated in US dollars, economic fundamentals were consistent with peso devaluation. The fixed exchange rate of the currency board was no longer consistent with the economic realities created by the expansionary fiscal policy, and an economic crisis erupted in late 2001 and early 2002 that resulted in a run on dollars as people tried to exchange pesos for dollars at the obviously overvalued exchange rate of 1 peso per dollar. The crisis in Argentina saw rioting in the streets, the resignations of two presidents in quick succession, a freeze on bank deposit withdrawals, and a break with the fixed exchange rate. Once the currency board arrangement was ended, the peso quickly fell in value from one-to-one parity with the US dollar to a level of 3 pesos per dollar. The Argentine case serves as a warning that currency boards are not a guarantee of forever-fixed exchange rates. If government policy is inconsistent with the fixed exchange rate, the currency board cannot last.

Appendix A shows that there are thirteen countries that have “dollarized.” Eight of the “dollarized” countries are using the US dollar as the official currency, three use the euro, and two use the Australian dollar. One major advantage of a “dollarized” economy is that there is no possibility of speculative attacks. In addition, the inflation rate comes from the adopted currency, generally leading to lower inflation rates for the “dollarized” economy. Finally, trade between the “dollarized” economy and other countries using the target currency becomes transparent, without any need to convert currencies or prices.

However, there are some drawbacks also with “dollarization.” The central bank of a “dollarized” economy does not perform in the usual way. They do not engage in the monetary policy actions typical of central banks. The central bank of Ecuador, for example, does not have any influence over the money supply in Ecuador. This means that the central bank loses its ability to serve as a lender of last resort to troubled banks. In addition, it loses all seigniorage benefits. As the bank no longer issues currency, it cannot collect any seigniorage revenue. Even in the currency board case some seigniorage revenue exists, although it is tied to the foreign currency returns rather than domestic currency. However, in a “dollarized” economy the seigniorage return goes to the issuer of the currency rather than the “dollarized” country.

Most “dollarized” countries are small in geographic size. For example, the Republic of San Marino is a small country, with about 30,000 inhabitants, surrounded by Italy. Because of its small size and geographic position, it is not surprising that the Republic of San Marino has chosen the euro as its currency. Note that even though the Republic of San Marino uses the euro, it is not part of the European Monetary Union and cannot vote in the European Central Bank (ECB). It has adopted the euro on its own, rather than apply for admission to the euro system. Because many of the traditional “dollarized” countries are small, the success or failure of using “dollarization” as a solution for developing countries is still debated. However, recently countries such as Ecuador and El Salvador have “dollarized.” In time these larger countries will provide more information about the applicability of “dollarization” to major developing economies.

Optimum Currency Areas

The optimum currency area can be defined as the geographical area that would maximize economic benefits by keeping the exchange rate fixed within the area. Looking at the real world, we might suggest that North America and Western Europe appear to be likely currency areas given the geographic proximity of Canada, Mexico, and the United States, as well as the geographic position of the Western European nations. Since exchange rates between US and Canadian dollars and the Mexican peso seem closely linked (certainly the peso and the US dollar had a long history of fixed exchange rates), we might expect these three countries to maintain pegged exchange rates with each other and to float versus the rest of the world. Europeans, in fact, have explicitly adopted such a regional optimum currency area arrangement with the euro.

One necessary criterion for an optimum currency area is that the region should have relatively costless mobility of the factors of production (labor and capital). As an illustration of this theory, suppose we have two countries, A and B, producing computers and cotton, respectively. Suddenly there is a change in tastes resulting in a shift of demand from computers to cotton. Country A will tend to run a deficit balance of trade and have an excess supply of labor and capital since the demand for computers has fallen, whereas country B will run a surplus and have an excess demand for labor and capital because of the increase in demand for its cotton.

To correct the balance of trade deficit, factors of production could move from A to B and thereby establish new equilibrium wages and prices in each region. If factors can freely and cheaply migrate from an area lacking jobs to an area where labor is in demand, then the mobility will restore equilibrium. This is because the unemployment in one area is remedied by migration. Thus, fixed exchange rates within the area will be appropriate.

If factors are immobile, then the equilibrium will have to be restored solely through a relative price change. Such a relative price change could take place, if A and B have different currencies. Therefore a geographic area that does not have free movement of factors of production would likely benefit from dividing the geographic area into two or more flexible exchange rate zones.

The European Monetary System and the Euro

The optimum currency area literature suggests that in a regional setting like Western Europe a system of fixed exchange rates might be appropriate. While the establishment of the common euro currency may be viewed as a kind of permanently fixed exchange rate, prior to the euro, a system to link currencies and limit exchange rate flexibility had been in place since the late 1970s. The European Monetary System (EMS) was established in March 1979. The EMS committed the member countries to maintaining small exchange rate fluctuations among themselves, while allowing for large fluctuations against outside currencies. The EMS worked quite well through the 1980s and led to optimism that the member nations eventually could evolve into a system with one ECB and one currency. It was in this spirit that the Maastricht Treaty was signed in December 1991 and a timetable for the evolution of the system was spelled out. The treaty called for:

![]() The immediate removal of restrictions on European flows of capital and greater coordination of monetary and fiscal policy.

The immediate removal of restrictions on European flows of capital and greater coordination of monetary and fiscal policy.

![]() The establishment of a European Monetary Institute (EMI) in January 1994 to coordinate monetary policies of the individual central banks and make technical preparations for a single monetary policy.

The establishment of a European Monetary Institute (EMI) in January 1994 to coordinate monetary policies of the individual central banks and make technical preparations for a single monetary policy.

![]() The irrevocable fixing of exchange rates among all member countries, with a common currency and a ECB in January 1997, at the earliest, and by January 1999, at the latest.

The irrevocable fixing of exchange rates among all member countries, with a common currency and a ECB in January 1997, at the earliest, and by January 1999, at the latest.

This last step did not occur until January 1999. The countries that moved to this last step of monetary union required their macroeconomic policy to converge to that of the other EMS countries. Convergence was defined as occurring when (a) the country’s inflation rate did not exceed the average of the lowest three member country rates by more than 1.5% points; (b) its interest rate on long-term government bonds did not exceed those of the three lowest-inflation members by more than 2% points; and (c) the country’s government budget deficit did not exceed 3% of GDP, and outstanding government debt did not exceed 60% of GDP.

The new European currency, the euro, made its debut on January 1,1999. The symbol is €, and the ISO code is EUR. Euro notes and coins began to circulate on January 1, 2002. In the transition years of 1999–2001, people used the euro as a unit of account, denominating financial asset values and transactions in euro amounts. Bank accounts were available in euros and credit transactions were denominated in euros. However, actual cash transactions were not made with euros until euro cash started circulating in 2002.

Prior to the beginning of the euro, the value of each of the “legacy currencies” of the euro-area countries was fixed in terms of the euro. Table 2.5 shows the exchange rates at which each of the old currencies was fixed in terms of the euro. For instance, 1 euro is equal to 40.3399 Belgian francs or 1.95583 German marks. Of course, the prior monies of each of the Eurozone countries no longer are used, having been replaced by the euro.

Table 2.5

Exchange rates of old national currencies replaced by the euro

| Former currency | 1 Euro |

| Belgian franc | BEF40.3399 |

| German mark | DEM1.95583 |

| Spanish peseta | ESP166.386 |

| Finnish markka | FIM5.94753 |

| French franc | FRF6.55957 |

| Greek drachma | GRD340.750 |

| Irish pound | IEP0.787564 |

| Italian lira | ITL1936.27 |

| Luxembourg franc | LUF40.3399 |

| Netherlands guilder | NLG2.20371 |

| Austrian schilling | ATS13.7603 |

| Portuguese escudo | PTE200.482 |

One currency requires one central bank, and the euro is no exception. The ECB began operations on June 1, 1998, in Frankfurt, Germany, and now conducts monetary policy for the Eurozone countries. The national central banks like the Bank of Italy or the German Bundesbank are still operating and perform many of the functions they had prior to the ECB, such as regulating and supervising banks and facilitating payments systems in each nation. In some sense they are like the regional banks of the Federal Reserve System in the United States. Monetary policy for the euro-area countries is conducted by the ECB in Frankfurt just as monetary policy for the United States is conducted by the Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C. Yet the national central banks of the euro-area play an important role in each of the respective countries. The entire network of national central banks and the ECB are called the European System of Central Banks. Monetary policy for the euro-area is determined by the Governing Council of the ECB. This council is comprised of the heads of the national central banks of the euro-area countries plus the members of the ECB Executive Board. The board is made up of the ECB president and vice-president and four others chosen by the heads of the governments of the euro-area nations.

The original 11 countries, that adopted the euro, were: Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, and Finland. The original 11 became 12, before the euro cash even circulated, when Greece joined in 2001. Recently several new member countries have been added. The EU members that have been added are: Cyprus, Estonia, Malta, Slovakia, Slovenia, Latvia, and Lithuania. That makes it 19 eurozone members as of May, 2016. In addition, small countries that are not part of the EU have unilaterally adopted the euro, for example, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican. In contrast, three member countries of the European Union in 1999 that were eligible have not adopted the euro and still maintain their own currencies and monetary policies. These three countries are Denmark, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It remains to be seen when, and if, these countries will ever become part of the Eurozone.

Summary

1. During the gold standard (1880–1914), currencies were convertible into gold at fixed exchange rates.

2. Fixed exchange rates broke down during the Interwar period (1918–1939). Many governments allowed their currencies to float as they suffered rapid inflation.

3. The Bretton Woods system (1944–1970) was an adjustable peg system, with every country fixing their currencies to an anchor currency (the US dollar) and the value of the anchor currency was fixed to gold. It is also called the “gold exchange standard” system.

4. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was created in 1944 to monitor the operations of the Bretton Woods system.

5. The Bretton Woods system was ended in 1973. Since then the major developed nations began floating their exchange rates.

6. SDR is a special currency issued by the IMF to use as international reserves and settle international accounts between central banks.

7. Reserve currencies serve as an international unit of account, a medium of exchange, and a store of value.

8. The current exchange rate arrangements range from peg (such as dollarization, currency board, and standard peg) to floating (such as managed floating and free floating).

9. Countries with a floating exchange rate tend to have large, closed economies, with inflation rates that differ from those of their trading partners, and trade diversified across many countries.

10. The optimum currency area is the geographical region that could gain economic efficiency by fixing exchange rates within a group and floating exchange rates with the rest of the world. An example of an optimum currency area arrangement is the euro.

11. One of the necessary conditions for the optimal currency area is perfect mobility of the factors of production.

12. The EMS was established in March 1979 to maintain small exchange rate fluctuations among member countries, while allowing for floating against outside currencies. The EMS has evolved into a system with one currency, the euro, and one ECB in 1999.

Exercises

1. What type of exchange rate system was the gold standard? Explain how it is operated.

2. How does the gold standard eliminate the possibility of continuous balance of payments disequilibria?

3. How did the Bretton Woods system differ from the gold standard? What was the primary purpose of the IMF under the Bretton Woods? Why did the Bretton Woods system finally collapse?

4. What is seigniorage? Does the United State possess an unfair advantage in world commerce due to seigniorage?

5. What is the difference between “dollarization” and a currency board?

6. What is the difference between managed floating and free floating exchange rates?

7. Discuss the common economic reasons for why a country should adopt a fixed exchange rate arrangement.

8. Explain and graphically illustrate how speculators can attack a currency under the fixed exchange rate system.

9. How can a target zone help create a more stable exchange rate? Explain.

10. In what way is the Euro system of central banks similar to the Federal Reserve System?

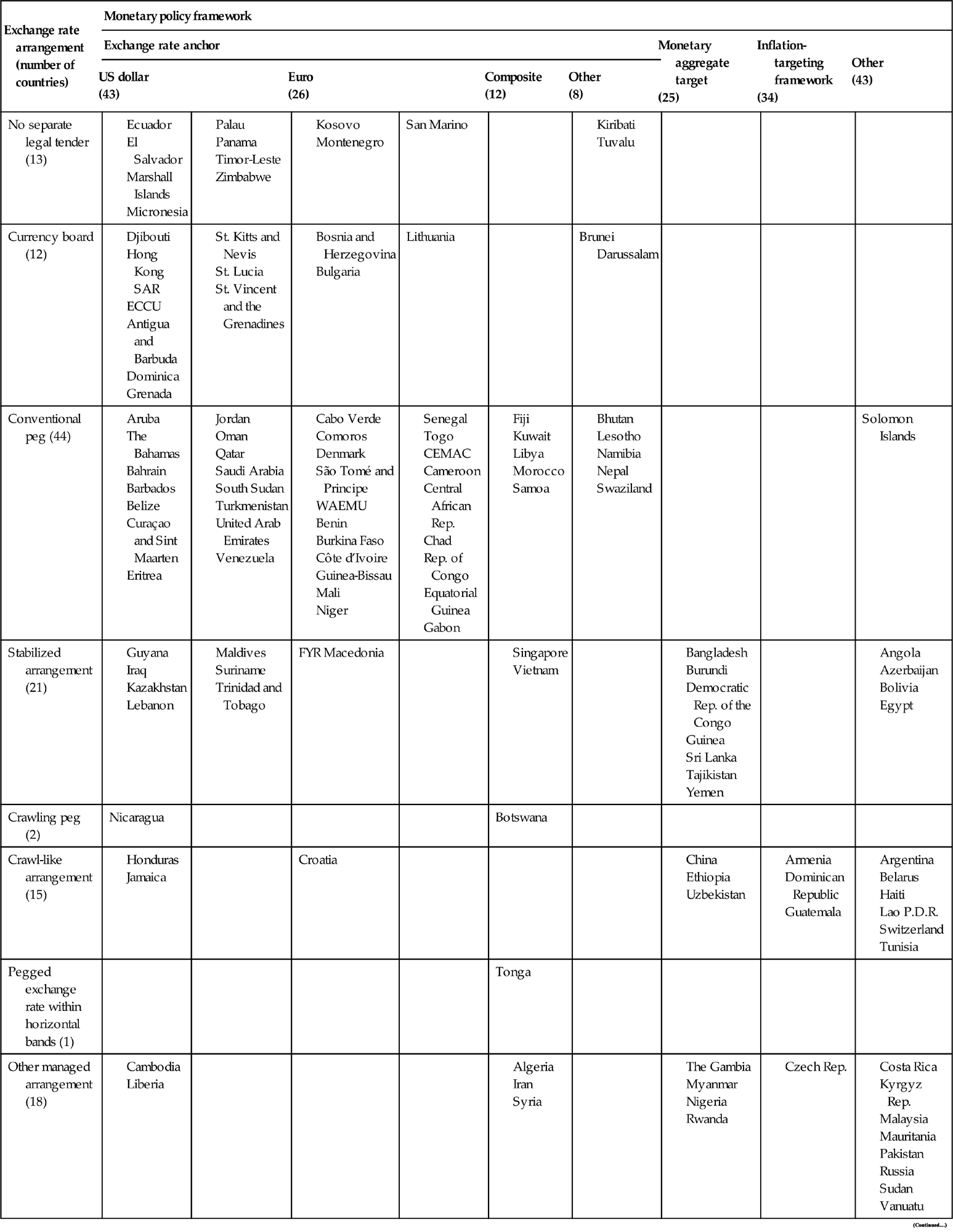

Appendix A Current Exchange Rate Arrangements

Table A.1 lists the exchange rate arrangements of the IMF member countries. In addition, information about the type of monetary policy framework that is used in the member countries is provided.

Table A.1

Source: Annual exchange rate arrangements and restrictions, October 2014, from IMF.org, 2015.