International Lending and Crises

Abstract

In this chapter international lending crises are explored, looking at both causes and results. The recent financial crisis and the Greek debt crisis are examined in particular detail, in its own sections. IMF loans and IMF conditionality, particularly in the case of Greece, are discussed. The role of corruption on a country’s economic growth is examined, and the chapter concludes with a detailed discussion of the important topic of country risk analysis.

Keywords

BlackRock Sovereign Risk Index; capital flight; country risk analysis; direct foreign investment; Great Recession; Greek debt crisis; IMF conditionality; international lending; International Monetary Fund (IMF)

In many ways, international lending is similar to domestic lending. Lenders care about the risk of default and the expected return from making loans whether they are lending across town or across international borders. In this chapter, we will continue our discussion of capital flows, by looking at international lending. In addition, the chapter will examine the problems that borrowing countries may experience.

International Lending

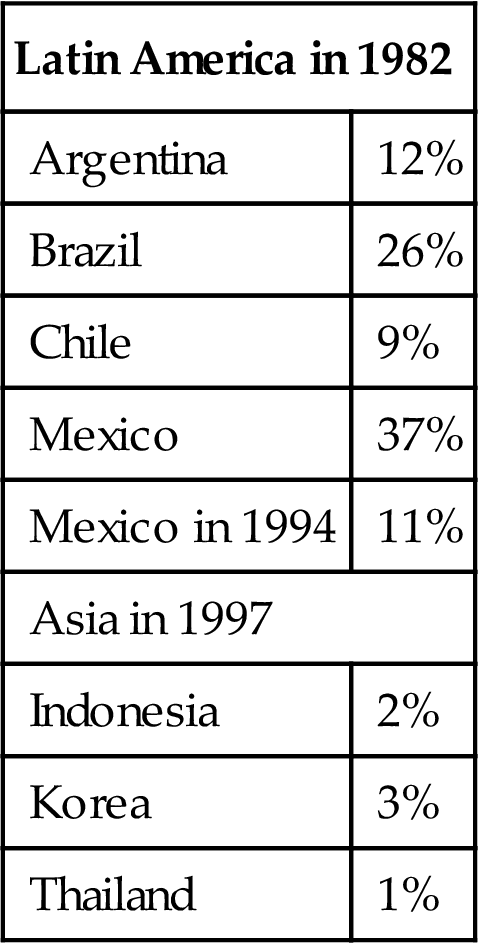

International lending has had recurrent horror stories where regional financial crises have imposed large losses on lenders. In the 1980s, there was a Latin American debt crisis in which many countries were unable to service the international debts they had accumulated. Table 11.1 illustrates the commitment of US banks to lending in each of the crisis areas. The table indicates that the situation from the perspective of US banks was much more dire in the 1982 Latin American crisis than in the more recent cases. The 1980 debtor nations owed so much money to international banks that a default would have wiped out the biggest banks in the world. As a result, debts were rescheduled rather than allowed to default. A debt rescheduling postpones the repayment of interest and principal so that banks can claim the loan as being owed in the future rather than in default now. This way, banks do not have to write off the debt as a loss—which would have threatened the existence of many large banks due to the large size of the loans relative to the capitalization of the bank. For instance, the Mexican debt to US banks in 1982 was equal to 37% of US bank capital. Banks simply could not afford to write off bad debt of this magnitude as loss. By rescheduling the debt, banks would avoid this alternative.

Table 11.1

US bank loans in financial crisis countries as a percentage of US bank capital

| Latin America in 1982 | |

| Argentina | 12% |

| Brazil | 26% |

| Chile | 9% |

| Mexico | 37% |

| Mexico in 1994 | 11% |

| Asia in 1997 | |

| Indonesia | 2% |

| Korea | 3% |

| Thailand | 1% |

Source: From Kamin, S., 1998. The Asian financial crisis in historical perspective: a review of selected statistics. Working Paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

In contrast to the heavy exposure of international banks to Latin American borrowers in 1982, the Asian financial crisis of 1997 involved a much more manageable debt position for US banks. Many international investors lost money in the Asian crisis, but the crisis did not threaten the stability of the world banking system to the extent the 1980s crisis did. However, the debtor countries required international assistance to recover from the crisis in all recent crisis situations. This recovery involves new loans from governments, banks, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Later in this chapter, we consider the role of the IMF in more detail. First, it is useful to think about what causes financial crises.

Causes of Financial Crises

The causes of the recent Asian financial crisis are still being debated. Yet, it is safe to say that certain elements are essential in any explanation, including external shocks, domestic macroeconomic policy, and domestic financial system flaws. Let us consider each of these in turn.

1. External shocks. Following years of rapid growth, the East Asian economies faced a series of external shocks in the mid-1990s that may have contributed to the crisis. The Chinese renminbi and the Japanese yen were both devalued, making other Asian economies with fixed exchange rates less competitive relative to China and Japan. Because electronics manufacturing is an important export industry in East Asia, another factor contributing to a drop in exports and national income was the sharp drop in semiconductor prices. As exports and incomes fell, loan repayment became more difficult and property values started to fall. Since real property is used as collateral in many bank loans, the drop in property values made many loans of questionable value so that the banking systems were facing many defaults.

2. Domestic macroeconomic policy. The most obvious element of macroeconomic policy in most crisis countries was the use of fixed exchange rates. Fixed exchange rates encouraged international capital flows into the countries, and many debts incurred in foreign currencies were not hedged because of the lack of exchange rate volatility. Once pressures for devaluation began, countries defended the pegged exchange rate by central bank intervention—buying domestic currency with dollars. Because each country has a finite supply of dollars, countries also raised interest rates to increase the attractiveness of investments denominated in domestic currency. Finally, some countries resorted to capital controls, restricting foreigners access to domestic currency to restrict speculation against the domestic currency. For instance, if investors wanted to speculate against the Thai baht, they could borrow baht and exchange them for dollars, betting that the baht would fall in value against the dollar. This increased selling pressure on the baht could be reduced by capital controls limiting foreigners’ ability to borrow baht. However, ultimately the pressure to devalue is too great, as even domestic residents are speculating against the domestic currency and the fixed exchange rate is abandoned. This occurs with great cost to the domestic financial market. Because international debts were denominated in foreign currency and most were unhedged because of the prior fixed exchange rate, the domestic currency burden of the debt was increased in proportion to the size of the devaluation. To aid in the repayment of the debt, countries turn to other governments and the IMF for aid.

3. Domestic financial system flaws. The countries experiencing the Asian crisis were characterized by banking systems in which loans were not always made on the basis of prudent business decisions. Political and social connections were often more important than expected return and collateral when applying for a loan. As a result, many bad loans were extended. During the boom times of the early to mid-1990s, the rapid growth of the economy covered such losses. However, once the growth started to falter, the bad loans started to adversely affect the financial health of the banking system. A related issue is that banks and other lenders expected the government to bail them out if they ran into serious financial difficulties. This situation of implicit government loan guarantees created a moral hazard situation. A moral hazard exists when one does not have to bear the full cost of bad decisions. If institutions or individuals taking the risk are assured of not being held liable for losses, then it creates excessive risk taking. So if banks believe that the government will cover any significant losses from loans to political cronies that are not repaid, they will be more likely to extend such loans.

Considerable resources have been devoted to understanding the nature and causes of financial crises in hopes of avoiding future crises and forecasting those crises that do occur. Forecasting is always difficult in economics, and it is safe to say that there will always be surprises that no economic forecaster foresees. Yet there are certain variables that are so obviously related to past crises that they may serve as warning indicators of potential future crises. The list includes the following:

1. Fixed exchange rates. Countries involved in recent crises, including Mexico in 1993–94, the Southeast Asian countries in 1997, and Argentina in 2002, all utilized fixed exchange rates prior to the onset of the crisis. Generally, macroeconomic policies were inconsistent with the maintenance of the fixed exchange rate. When large devaluations ultimately occurred, domestic residents holding unhedged loans denominated in foreign currency suffered huge losses.

2. Falling international reserves. The maintenance of fixed exchange rates may be no problem. One way to detect whether the exchange rate is no longer an equilibrium rate is to monitor the international reserve holdings of the country (largely the foreign currency held by the central bank and treasury). If the stock of international reserves is falling steadily over time, that is a good indicator that the fixed exchange rate regime is under pressure and there is likely to be a devaluation.

3. Lack of transparency. Many crisis countries suffer from a lack of transparency in governmental activities and in public disclosures of business conditions. Investors need to know the financial situation of firms in order to make informed investment decisions. If accounting rules allow firms to hide the financial impact of actions that would harm investors, then investors may not be able to adequately judge when the risk of investing in a firm rises. In such cases, a financial crisis may appear as a surprise to all but the “insiders” in a troubled firm. Similarly, if the government does not disclose its international reserve position in a timely and informative manner, investors may be caught by surprise when a devaluation occurs. The lack of good information on government and business activities serves as a warning sign of potential future problems.

This short list of warning signs provides an indication of the sorts of variables an international investor must consider when evaluating the risks of investing in a foreign country. Once a country finds itself with severe international debt repayment problems, it has to seek additional financing. Because international banks are not willing to commit new money where prospects for repayment are slim, the IMF becomes an important source of funding. Before we examine the role of the IMF, we will examine the recent financial crisis in the United States and the debt crisis in Greece.

International Lending and the Great Recession

The recent financial crisis shares some similarities with past crises, but is also different in some ways. The recent crisis, starting in the end of 2007, has been called the Great Recession, because of its sharp effect on output across the world. Economists are still debating the causes of the crisis, but some general observations can be made. The Great Recession was caused by an overexpansion of credit and a lack of transparency into the riskiness of the investments. This is similar to the Asian financial crisis. However, the transmission effect of the crisis was a bit different for the Great Recession than the Asian financial crisis. The effects of the US housing crisis were transmitted throughout the international financial world from a highly interconnected global financial market. Specifically, the sharp increase in securitization during the beginning of the 2000s integrated financial markets across the world and led to an unexpected systemic risk. Systemic risk is the possibility that an event, such as a failure of a single firm, could have a serious effect on the entire economy.

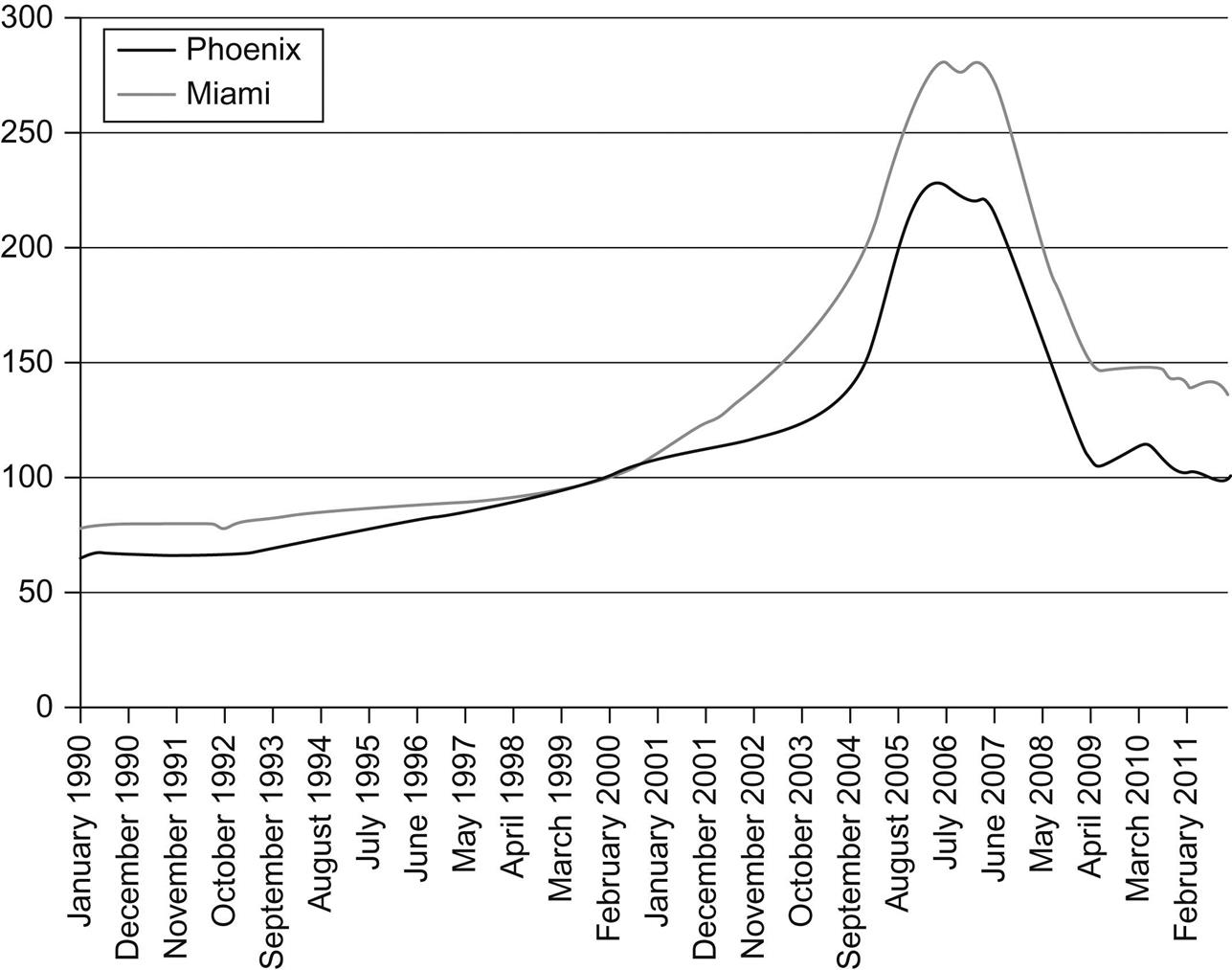

The beginning of the crisis occurred in the housing sectors in five states in the United States, namely: Arizona, California, Florida, Nevada, and Virginia. The housing market crash in these five states caused financial markets across the world to momentarily break down. How could the housing market in a few states cause such a big effect? The answer lies in the way mortgage lending has become an international market. Fig. 11.1 shows the home prices in two big US cities. These two cities are typical for the price behavior in the five states, experiencing the housing market crash. Fig. 11.1 shows how from 2001 to 2006 home prices rapidly increased, and then in 2007 the prices fell back down even faster. Note that, in particular, in 2004–06 the prices in both cities show a remarkable rise.

The sharp fall in home price in the United States appeared to have been a surprise for home speculators and also for some mortgage investors. The delinquency rates on mortgages rose to unprecedented levels, as seen in Fig. 11.2. The large increase in foreclosures and short sales, following the fall of home prices, resulted in mortgage losses to banks and other financial investors. However, such losses were not confined only to the domestic US financial markets. Instead, financial markets across the world were affected by the US mortgage problems.

The reason for the spread of the losses across the world was the high degree of securitization of the US mortgages. The process of home ownership in the United States involves a loan originator, using money from an original lender for the mortgage. The original lender rarely holds the loan, instead bundling mortgages into a Mortgage Backed Security (MBS). This practice enables the loan originator to continue lending, thereby increasing the availability of mortgage funds. The loan originator charges a fee, but does not end up with the risk of the loan not being repaid. The fact that the loan originator did not end up holding the mortgage resulted in less careful screening of individuals applying for home loans.

Once the original lender has a sufficient number of mortgages, the lender will bundle the mortgages into an MBS. An MBS is a number of different mortgages that are bundled together and sold in such a way that different MBS products have different risk levels. In this way, investors can choose how high a risk they are willing to accept. To reduce the risk, one can also buy a hedge for default risk, such as a Credit Default Swap (CDS) that we discussed in Chapter 4, Forward-Looking Market Instruments.

The MBS makes it easy for investors across the world to invest in the US housing market. It is almost impossible for a foreign bank to offer a mortgage to an individual in the United States, because of the monitoring costs of the loan. However, an MBS is a bundle of mortgages with a specific risk. Thus international investors do not need to worry about what the MBS contains. This made international investment in MBSs particularly attractive. In addition, the MBS could be hedged using the CDS market, which made the international investors feel protected. Therefore, loans to individuals that are seen as risky (subprime or nonprime loans) increased with the introduction of the MBS market. According to DiMartino and Duca (2007) nonprime loans increased from 9% of new mortgages in 2001 to 40% in 2006.

The MBS and CDS markets grew sharply in 2004–07. The CDS market was $6.4 trillion in 2004 and grew to $57.9 trillion in 2007. However, the protection had one flaw: There still was a counterparty risk. A counterparty risk is the risk that a firm that is part of the hedge defaults. Thus, one can set up a perfect hedge against default risk of the MBS, but if one firm that sold you the CDS defaults then your investment is suddenly unhedged. Once your portfolio is unhedged, your chance of default increases. Thus, one firm defaulting can have a spreading effect across financial institutions and individuals across the globe. In general, this systemic risk seems to have been unanticipated by the financial market.

In March 2008, the first major problem appeared with Bear Stearns, an investment bank in the United States, nearing bankruptcy. Bear Stearns was highly interconnected with both domestic and international financial markets through MBSs and CDSs. To forestall the systemic risk possibility, the Federal Reserve and Treasury decided to intervene. However, when Lehman Brothers ran into the same type of problem in October 2008, it was allowed to go into bankruptcy. At the time of its bankruptcy, Lehman had close to a million CDS contracts, with hundreds of firms all over the world. Therefore the ripple effects from Lehman Brothers default were felt throughout the world with the cost of risk hedges increasing sharply and many banks and financial firms edging closer to bankruptcy. In the United States, Countrywide (the largest US mortgage lender) failed and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the largest backers of mortgages in the United States) were taken over by the government. In addition, the world’s largest insurance company, AIG, became virtually bankrupt in October 2008, primarily due to CDS problems. In the rest of the world, major financial companies defaulted or were taken over by the government. For example, in the United Kingdom Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley were taken over by the UK government, while in Iceland the whole banking system defaulted pushing the entire country into default in October 2008.

The reason for the multitude of bankruptcies across the world was the high levels of leverage for many financial institutions. Financial institutions need to have equity to back up the loans they make. The more equity they have, the lower the leverage level. Let us assume that you have $1, and lend it to Sam for 10% interest. You now will receive an interest payment of 10 cents when the loan matures. In this example the leverage level is one, because your equity (the cash you invested in the company) is equal to your assets (the loan you made). Now assume that you want to lend $10 more to Joe. You are out of cash to lend Joe so you borrow money from Roger (at 5%) to lend to Joe (at 10%). You now have $1 in equity plus $10 in liabilities (to Roger) and assets of $11. Your leverage level is now 11 to 1. Note that the higher the leverage level, the higher your profit will be, unless someone defaults. If Joe defaults on his loan then you do not have any equity to pay back your loan, and consequently have to go bankrupt. The higher the leverage level is, the higher the risk that you will become bankrupt from a bad loan.

Traditional banks have to hold liquid capital to back up their asset portfolios. The riskier the assets are, the higher the capital that is required to hold. To prevent bank insolvency, the Bank for International Settlements, located in Switzerland, sets the international rules for capitalization of banks. The most recent framework is called the Basel III rules. In addition to the Basel III regulation, the Federal Reserve sets additional rules for US banks. In contrast, investment banks and hedge funds have fewer rules. Thus, they may have higher leverage levels than traditional banks. At the start of the Great Recession, many investment banks had leverage ratios of 30 to 1, meaning that 30 dollars of assets had only 1 dollar of equity. Even a small reduction in the value of the assets wiped out the equity, making the financial institution insolvent.

International Lending and the Greek Debt Crisis

The Greek debt crisis of 2010 followed the Great Recession and was related to the response of the financial industries to the financial crisis. Greece has struggled with fiscal deficits for a long time and succeeded in reducing the fiscal deficit far enough to join the Eurozone in 2001. Fig. 11.3 shows the fiscal deficit shrinking from more than 10% of GDP in 1995 to slightly less than 4% in 2001. However, the fiscal deficits grew worse again in the 2000s. Gradually the fiscal deficit returned to the 10% mark in 2008 and bottomed out at 16% in 2009!

In addition to the fiscal deficit, Fig. 11.3 also shows the current account deficit. In the 2000s the fiscal deficit and the current account deficits both increase rapidly. This implies that the cause of the current account deficit was foreign capital flows financing the fiscal deficit. In Chapter 3, The Balance of Payments, we discussed such a situation as a case of “twin deficits.” Government borrowing pressured up interest rates and attracted financial investment from Germany and other countries. The use of foreign funds to finance the government borrowing made it easier for Greek people to continue consuming, because they did not have to buy government debt themselves. In addition, the foreign financial flows meant that the Greek government was not pressured to reduce government spending or raise taxes to eliminate the fiscal deficit.

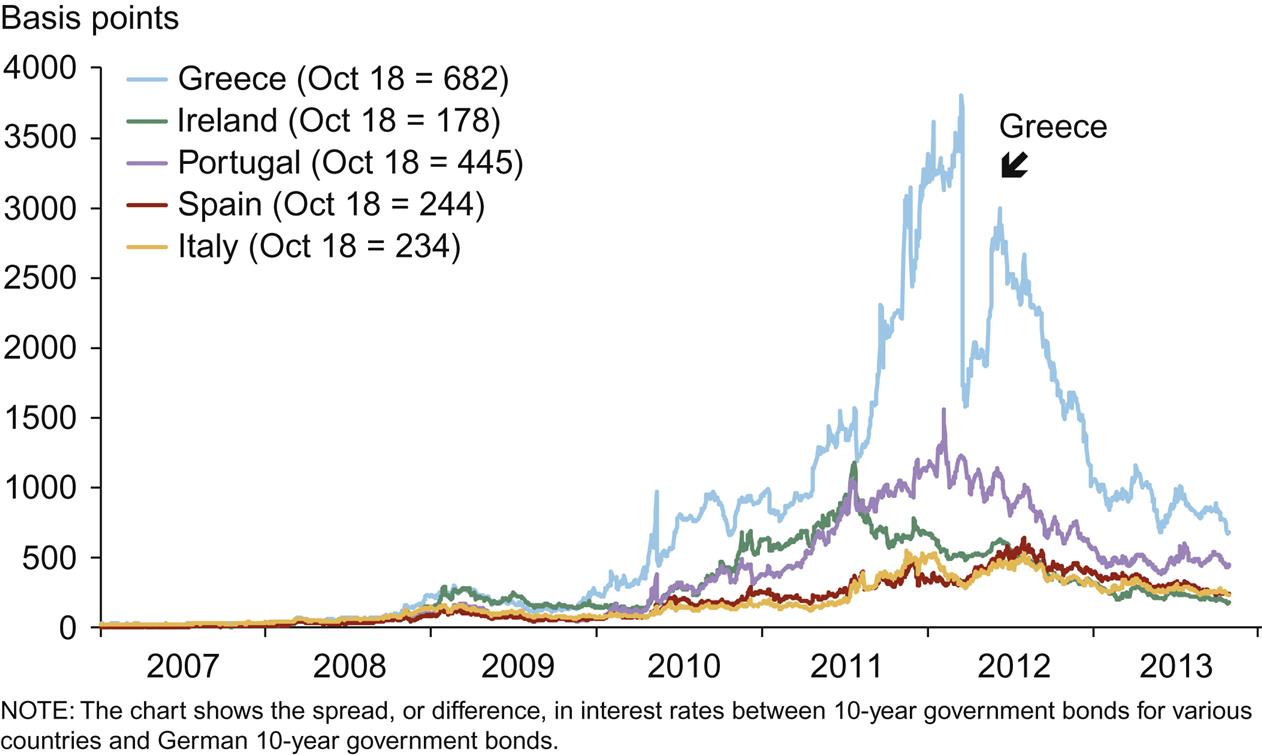

The convenient position of using foreign financial flows to pay for the fiscal deficit came to an end after the Great Recession. When the US financial crisis spread through the world in 2008, financial firms became cautious about taking on risk, following the default of several major financial firms. The lack of risk appetite led to a sharp increase in the cost of hedging risk. This affected firms, municipalities, states, and countries that had high indebtedness. Among the countries affected was Greece, which saw its cost of funds increasing sharply. Fig. 11.4 illustrates the added cost of borrowing for selected countries in comparison to the cost of borrowing for Germany. The figure illustrates that the cost of borrowing for Greece was at par with Germany in 2007 and only slightly more in 2008–09. However, in the 2010–12 period the cost of borrowing skyrocketed for Greece. At one point Greece had to pay over 3500 basis points (35 percentage points) more than Germany! The tremendously high borrowing costs meant that the Greek government had to increase its borrowing just to finance the cost of borrowing. Clearly this was not a sustainable position. In May 2010 Greece had no choice but to ask the IMF for assistance. In the next section, we look at how the role of the IMF has changed from supervising the Bretton Woods system to a lender of last resort.

IMF Conditionality

The IMF has been an important source of loans for debtor nations experiencing repayment problems. The importance of an IMF loan is more than simply having the IMF “bail out” commercial bank and government creditors. The IMF requires borrowers to adjust their economic policies to reduce balance of payments deficits and improve the chance for debt repayment. Such IMF-required adjustment programs are known as IMF conditionality.

Part of the process of developing a loan package includes a visit to the borrowing country by an IMF mission. The mission comprises economists who review the causes of the country’s economic problems and recommend solutions. Through negotiation with the borrower, a program of conditions attached to the loan is agreed upon. The conditions usually involve targets for macroeconomic variables, such as money supply growth or the government deficit. The loan is disbursed at intervals, with a possible cutoff of new disbursements if the conditions have not been met.

The importance of IMF conditionality to creditors can now be understood. Loans to sovereign governments involve risk management from the lenders’ point of view just as loans to private entities do. Although countries cannot go out of business, they can have revolutions or political upheavals leading to a repudiation of the debts incurred by the previous regime. Even without such drastic political change, countries may not be able or willing to service their debt due to adverse economic conditions. International lending adds a new dimension to risk since there is neither an international court of law to enforce contracts nor any loan collateral aside from assets that the borrowing country may have in the lending country. The IMF serves as an overseer that can offer debtors new loans if they agree to conditions. Sovereign governments may be offended if a foreign creditor government or commercial bank suggests changes in the debtor’s domestic policy, but the IMF is a multinational organization of over 180 countries. The members of the IMF mission to the debtor nation will be of many different nationalities, and their advice will be nonpolitical. However, the IMF is still criticized at times as being dominated by the interests of the advanced industrial countries. In terms of voting power, this is true.

Votes in the IMF determine policy, and voting power is determined by a country’s quota. The quota is the financial contribution of a country to the IMF and it entitles membership. Each country receives 250 votes, plus one additional vote for each SDR100,000 of its quota. (At least 75% of the quota may be contributed in domestic currency, with less than 25% paid in reserve currencies or SDRs.) Table 11.2 shows that the United States has by far the most votes, at 16.6% of the total votes. Japan and China follow with slightly more than 6% of the votes. Although the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) are becoming more powerful in terms of votes, the United States, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom together have almost 40% of the votes in the IMF. With such a large share of the votes, these five developed countries can dominate voting, especially with the help of other smaller European countries.

Table 11.2

Top 10 countries with most votes in the IMF 2016

| Country | Votes (in %) |

| United States | 16.6 |

| Japan | 6.2 |

| China | 6.1 |

| Germany | 5.3 |

| France | 4.1 |

| United Kingdom | 4.1 |

| Italy | 3 |

| India | 2.6 |

| Russia | 2.6 |

| Brazil | 2.2 |

Source: From http://IMF.org

The IMF has been criticized for imposing conditions that restrict economic growth and lower living standards in borrowing countries. The typical conditionality involves reducing government spending, raising taxes, and restricting money growth. For example, in May 2010, Greece signed a €30 billion loan agreement with the IMF. In addition, the European Union agreed to provide funds making the total financing package reach €110 billion. At the heart of the agreement Greece would impose fiscal discipline that would reduce the budget deficit from its 15.4% level in 2009, to well below 3% of GDP by 2014. To accomplish this the Greek authorities committed to reduce government spending and increase taxes. Note that in this case monetary growth was not an issue as Greece belonged to the Eurozone and cannot adjust monetary growth.

In the original statement by the IMF and Greek authorities, it is recognized that the austerity package could lead to short-run output contraction. However, the view was that the structural reforms and fiscal discipline would improve the competitiveness and long-run recovery of the economy. Such policies may be interpreted as austerity imposed by the IMF, but the austerity is intended for the borrowing government in order to permit the productive private sector to play a larger role in the economy.

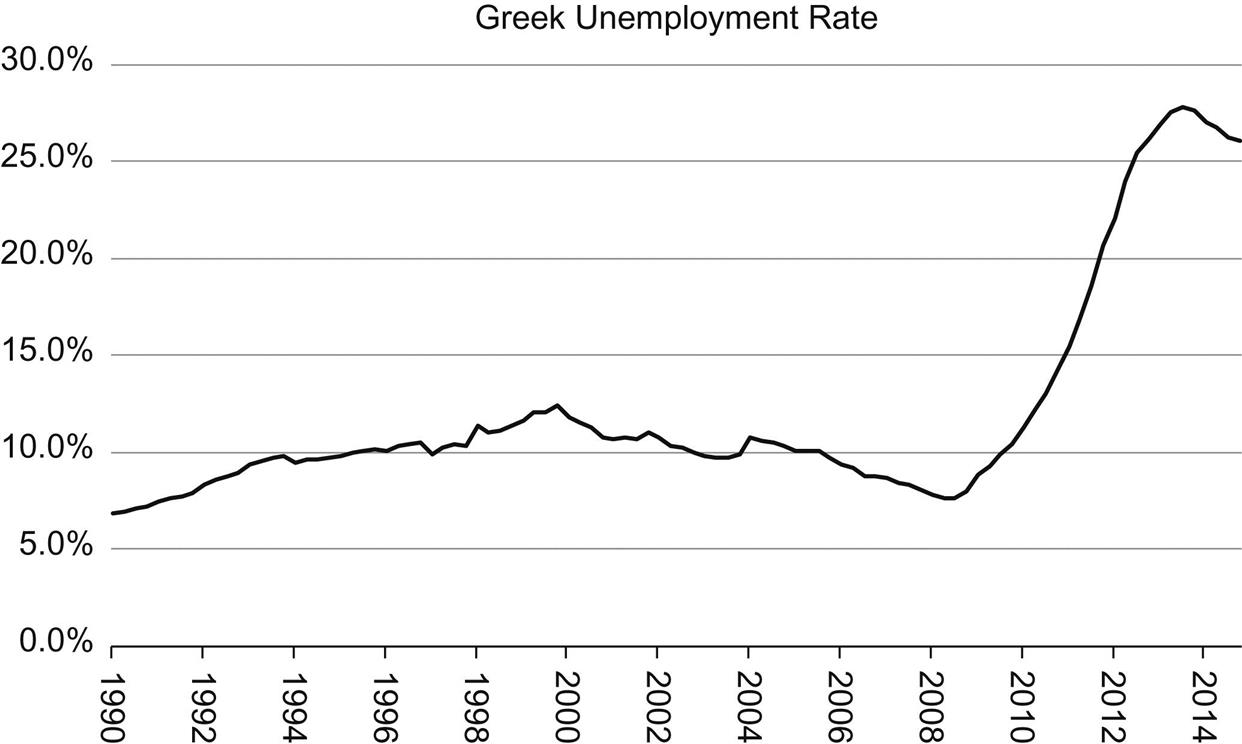

The view of the IMF is that adjustment programs are unavoidable in debtor countries facing repayment difficulties. However, the short-run contraction can be quite burdensome. In Greece, for example, the unemployment rate increased substantially. Fig. 11.5 shows the Greek unemployment rate. From a usual unemployment at or below 10% the unemployment skyrocketed to over 25% in a 5-year period. With one in four unemployed it leaves citizens with much time to be upset about the current conditions. Consequently it is no surprise that Greece has had more than a half dozen changes in government since 2009. The IMF maintains that adjustments required are those that promote long-run growth. While there may indeed be short-run costs of adjusting to a smaller role for government and fewer and smaller government subsidies, in the long run the required adjustments should stimulate growth to allow debt repayment.

The Role of Corruption

Corrupt practices by government officials have long reduced economic growth. Payment of money or gifts in order to receive a government service or benefit is quite widespread in many countries. Research shows that there is a definite negative relationship between the level of corruption in a country and both investment and growth.

Research shows that corruption thrives in countries where government regulations create distortions between the economic outcomes that would exist with free markets and the actual outcomes. For instance, a country where government permission is required to buy or sell foreign currency will have a thriving black market in foreign exchange where the black market exchange rate of a US dollar costs much more domestic currency than the “official rate” offered by the government. This distortion allows government officials an opportunity for personal gain by providing access to the official rate.

Generally speaking, the more competitive a country’s markets are, the fewer the opportunities for corruption. So policies aimed at reducing corruption typically involve reducing the discretion that public officials have in granting benefits or imposing costs on others. This may include greater transparency of government practices and the introduction of merit-based competitions for government employment. Due to the sensitive political nature of the issue of corruption in a country, the IMF has only recently begun to include this issue in its advisory and lending functions. When loans from the IMF or World Bank are siphoned off by corrupt politicians, the industrial countries providing the major support for such lending are naturally concerned and pressure the international organizations to include anticorruption measures in loan conditions. In the late 1990s, both the IMF and World Bank began explicitly including anticorruption policies as part of the lending process to countries when severe corruption is ingrained in the local economy.

Country Risk Analysis

International financial activity involves risks that are missing in domestic transactions. There are no international courts to enforce contracts and a bank cannot repossess a nation’s collateral, because typically no collateral is pledged. Problem loans to sovereign governments have received most of the publicity, but it is important to realize that loans to private firms can also become nonperforming because of capital controls or exchange rate policies. In this regard, even operating subsidiary units in foreign countries may not be able to transfer funds to the parent multinational firm, if foreign exchange controls block the transfer of funds.

It is important for commercial banks and multinational firms to be able to assess the risks involved in international deals. Country risk analysis has become an important part of international business. Country risk analysis refers to the evaluation of the overall political and financial situation in a country and the extent to which these conditions may affect the country’s ability to repay its debts. In determining the degree of risk associated with a particular country, we should consider both qualitative and quantitative factors. The qualitative factors include the political stability of the country. Certain key features may indicate political uncertainty:

1. Splits between different language, ethnic, and religious groups that threaten to undermine stability.

2. Extreme nationalism and aversion to foreigners that may lead to preferential treatment of local interests and nationalization of foreign holdings.

3. Unfavorable social conditions, including extremes of wealth.

4. Conflicts in society evidenced by frequency of demonstrations, violence, and guerrilla war.

Besides the qualitative or political factors, we also want to consider the financial factors that allow an evaluation of a country’s ability to repay its debts. Country risk analysts examine factors such as these:

1. External debt. Specifically, this is the debt owed to foreigners as a fraction of GDP or foreign exchange earnings. If a country’s debts appear to be relatively large, then the country may have future repayment problems.

2. International reserve holdings. These reserves indicate the ability of a country to meet its short-term international trade needs should its export earnings fall. The ratio of international reserves to imports is used to rank countries according to their liquidity.

3. Exports. Exports are looked at in terms of the foreign exchange earned as well as the diversity of the products exported. Countries that depend largely on one or two products to earn foreign exchange may be more susceptible to wide swings in export earnings than countries with a diversified group of export products.

4. Economic growth. Measured by the growth of real GDP or real per capita GDP, economic growth may serve as an indicator of general economic conditions within a country.

Although no method of assessing country risk is foolproof, by evaluating and comparing countries on the basis of some structured approach, international lenders have a base on which they can build subjective evaluations of whether to extend credit to a particular country.

Recognizing the desire of investors to have reliable information about country risk, BlackRock Investment Institute launched a new ranking of country risk in 2011. This ranking ranks countries according to the likelihood of debt default, devaluation of the currency or above-trend deflation. Foreign investors would not only be concerned about a country defaulting on the debt, but would also be concerned about a sharp loss of the foreign currency value by a high inflation or devaluation of the currency.

There are four components to BlackRock’s country risk analysis:

1. Fiscal Space, with a 40% weight, examines several macroeconomic factors that could lead to a debt path that is unsustainable.

2. External Finance Position, with a 20% weight, examines the vulnerability of a country to external shocks.

3. Financial Sector Health, with a 10% weight, measures the risk exposure that the private sector banks impose on the country’s financial health.

4. Willingness to Pay, with a 30% weight, measures how a country’s institutions can handle debt payment.

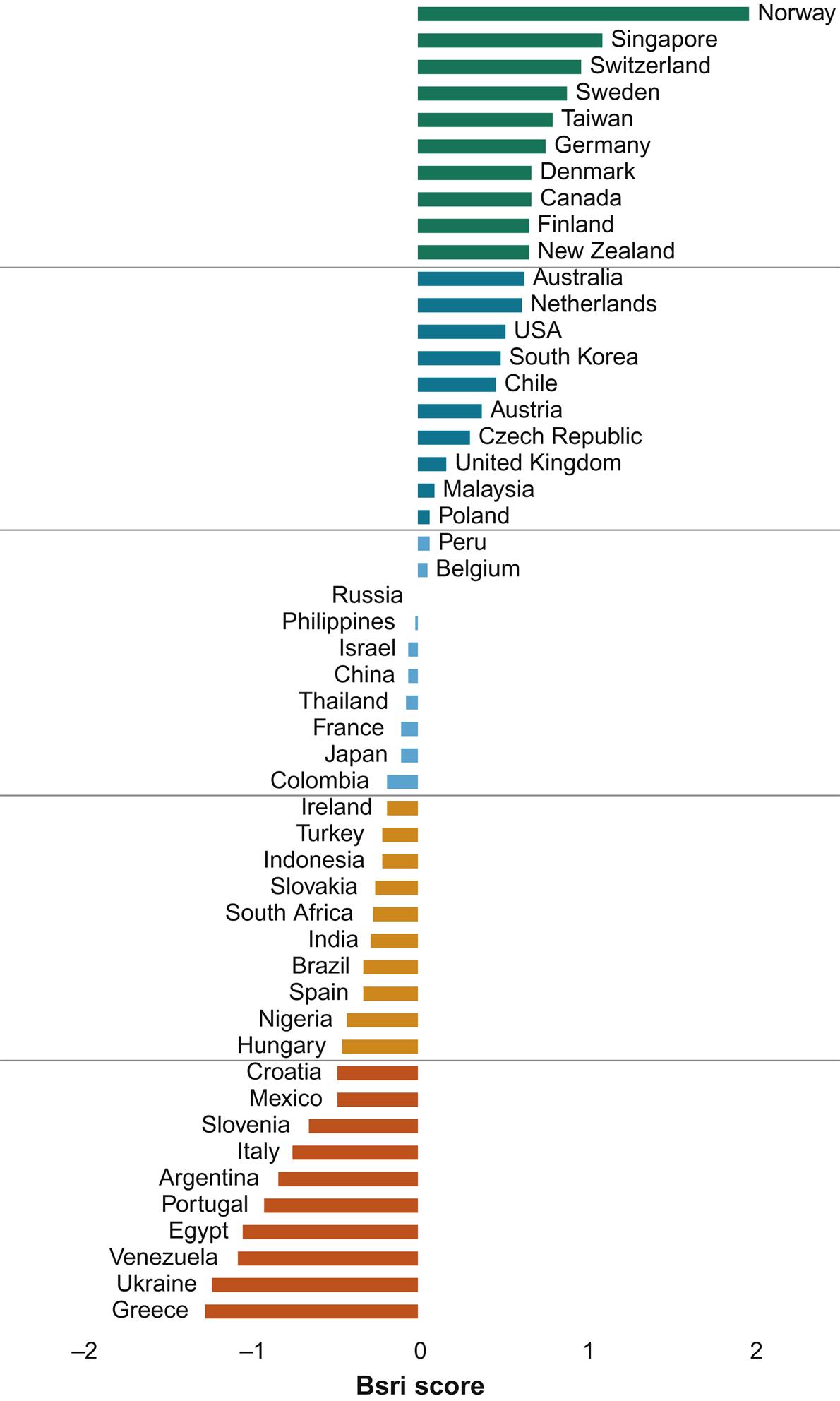

The first three components deal with a country’s ability to pay, whereas the last one deals with the willingness to pay. Fig. 11.6 shows the results of the July 2015 ranking of country risk.

The Scandinavian countries are ranked very high in the index. Norway leads the index, with Sweden, Finland, and Denmark also in the top 10. Norway has extremely low levels of debt and has strong institutions backing the country. On the other extreme are countries with large levels of debt or high political instability. The Euro debt crisis still remains a problem resulting in Greece, Portugal, Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy ranking among the lowest 10 countries. Others among the bottom 10 countries are having political instability, such as Ukraine, Venezuela, and Egypt. The United States ranks 13th, close to the top among the second tier of countries in the risk index. Note also that the differences are small between the score that United States has and the scores of the five countries ahead, implying that from the view of riskiness, the top 20 countries in the ranking have a relatively low riskiness.

Summary

1. The Latin American debt crisis in the 1980s had threatened the solvency of large banks and creditors, so debts were rescheduled to postpone the repayments rather than allowed for default.

2. The causes of the Asian financial crisis of 1997 were external shocks, weak macroeconomic fundamentals, and domestic financial system flaws.

3. A fixed exchange rate system, a decline in foreign reserves, and a lack of transparency in governmental activities could serve as warning indicators of potential financial crisis.

4. The Great Recession of 2008–09 in the United States spread to global financial markets because foreign investors had invested in MBSs backed by US mortgages.

5. Since the risk of MBS could be hedged by using CDS market, many investors felt protected and highly leveraged their investments. This practice led to bankruptcies of several giant investment banks.

6. When a country seeks financial assistance from IMF to overcome its problem, the government is subject to a set of agreed macroeconomic policy changes and structural reforms, known as the IMF conditionality, to ensure ability to repay the loan.

7. The IMF has included a clause of anticorruption into its lending process.

8. Country risk analysis is the evaluation of a country’s overall political and financial situations that may influence the country’s ability to repay its loans.

9. Country risk analysis is based on structural modeling of variables such as the amount of external debt to GDP, international reserve holdings, the volume of exports, and the pace of economic growth.

Exercises

1. Why would a debtor nation prefer to borrow from a bank rather than the IMF, other things being equal? Can “other things” ever be equal between commercial bank and IMF loans?

2. Pick three developing countries and create a country risk index for them. Rank them ordinally in terms of factors that you can observe (like exports, GDP growth, reserves, etc.) by looking at International Financial Statistics published by the IMF. Based on your evaluation, which country appears to be the best credit risk? How does your ranking compare to that found in the most recent BlackRock Investment survey?

3. How did each of the following contribute to the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s: external shocks, domestic macroeconomic policy, and domestic financial system flaws?

4. Explain how the fixed exchange rate arrangement could lead to a financial crisis.

5. Imagine yourself in a job interview for a position with a large international bank. The interviewer mentions that, recently, the bank has experienced some problem loans to foreign governments. The interviewer asks you what factors you think the bank should consider when evaluating a loan proposal involving a foreign governmental agency. How do you respond?

6. Explain what a highly leveraged investment practice is. How does it relate to financial crisis?