4. Individuality in Learning and the Concept of Learning Styles

But the complicated external conditions under which we live, as well as the presumably even more complex conditions of our individual psychic disposition, seldom permit a completely undisturbed flow of our psychic activity. Outer circumstances and inner disposition frequently favor the one mechanism, and restrict or hinder the other; whereby a predominance of one mechanism naturally arises. If this condition becomes in any way chronic, a type is produced, namely an habitual attitude, in which the one mechanism permanently dominates; not, of course, that the other can ever be completely suppressed, inasmuch as it also is an integral factor in psychic activity. Hence, there can never occur a pure type in the sense that he is entirely possessed of the one mechanism with a complete atrophy of the other. A typical attitude always signifies the merely relative predominance of one mechanism.

—Carl Jung, Psychological Types

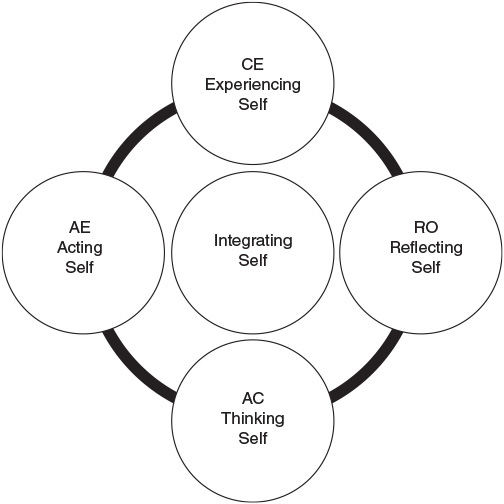

The structural model of the learning process described in the last chapter is a complex one, capable of producing a rich variety of learning processes that vary widely in subtlety and complexity. The model gives the basic prehension processes of apprehension and comprehension independent structural status. The same is true for the transformation processes of intention and extension. In addition, apprehension and comprehension as well as intention and extension are dialectically related to one another, such that their synthesis produces higher levels of learning. Thus, the learning process at any given moment in time may be governed by one or all of these processes interacting simultaneously. Over time, control of the learning process may shift from one of these structural bases for learning to another. Thus, the structural model of learning can be likened to a musical instrument and the process of learning to a musical score that depicts a succession and combination of notes played on the instrument over time. The melodies and themes of a single score form distinctive individual patterns that we will call learning styles.

The Scientific Study of Individuality

In this analogy, I am suggesting that the learning process is not identical for all human beings. Rather, it appears that the physiological structures that govern learning allow for the emergence of unique individual adaptive processes that tend to emphasize some adaptive orientations over others. When the matter is viewed from an evolutionary perspective, there appears to be good reason for this variability and individuality in human learning processes.

Human individuality does not just result from random deviations from a single normative blueprint; it is a positive, adaptive adjustment of the human species. If there are evolutionary pressures toward “the survival of the fittest” in the human species, these apply not to individuals but to the human community as a whole. Survival depends not on the evolution of a race of identical supermen but on the emergence of a cooperative human community that cherishes and utilizes individual uniqueness (compare Levy, 1980).

Attempts to understand the nature of human individuality and to describe the essential dimensions along which individuals vary began long before psychology was a recognized field of inquiry. For example, gnostic philosophers of the second century conceived of human variability as occurring along three dimensions: the pneumatici (thinking orientation), the psychici (feeling orientation), and the hylici (sensation orientation). In the eighteenth century, the poet and philosopher Fredrich Schiller divided people into “naive” and sentimental types, paralleling realist and idealist philosophical orientations. In the century that followed, Nietzsche developed the famous Apollonian and Dionysian typology. In 1923, Carl Jung combined these and other approaches to individuality into what must be considered one of the most important books on individual differences ever written, Psychological Types. Today, psychology abounds with every type of individual difference measures—in traits, values, motives, attitudes, cognitive styles, and so on (compare Tyler, 1978).

The scientific study of human individuality poses some fundamental dilemmas. The human sciences, unlike the physical sciences, place an equal emphasis on the discovery of general laws that apply to all human beings and on the understanding of the functioning of the individual case. In chemistry, for example, a researcher is apt to discard a sample of a given compound if it does not perform as the general laws of chemistry indicate it should. Impurities or contaminants in the sample are usually seen as irrelevant-error variance to be eliminated. In the human sciences, however, each sample is a human being whose uniqueness and individuality are highly prized, particularly by the person him- or herself. We are interested, therefore, not only in general laws of behavior, but in their specific relevance and application for each individual case. The basic dilemma for the scientific study of individual differences, therefore, is how to conceive of general laws or categories for describing human individuality that do justice to the full array of human uniqueness.

Theories describing psychological types or personality styles have been much criticized in this regard. Psychological categorizations of people such as those depicted by psychological “types” can too easily become stereotypes that tend to trivialize human complexity and thus end up denying human individuality rather than characterizing it. In addition, type theories often have a static and fixed connotation to their descriptions of individuals, lending a fatalistic view of human change and development. This view often gets translated into a self-fulfilling prophecy, as with the common educational strategy of “tracking” students on the basis of individual differences and thereby perhaps reinforcing those differences. Another problem with type theories is that they tend to become somewhat idealized. Descriptions tend to be cast in the form of “pure” types, with the caveat that no person actually represents a pure type. We are thus left with the problem of describing and attempting to research an ideal profile that does not exist empirically.

These problems with type theories seem to stem from the underlying epistemology on which they are based. Type theories, like many scientific theories, have tended to be based on the epistemological root metaphor of formism (see Chapter 5 for further elaboration of the role of root metaphors in epistemology). In the formist epistemology, forms or types are the ultimate reality, and individual particulars are simply imperfect representations of the universal form or type. Type theories thus easily fall into the problems identified above. An alternative epistemological root metaphor, one that we will use in our approach to understanding human individuality, is that of contextualism. In contextualism, the person is examined in the context of the emerging historical event, in the processes by which both the person and event are shaped. In the contextualist view, reality is constantly being created by the person’s experience. As Dewey notes, “an individual is no longer just a particular, a part without meaning save in an inclusive whole, but is a subject, self, a distinctive centre of desire, thinking and aspiration” (1958, p. 216).

The implication of the contextualist world view for the study of human individuality is that psychological types or styles are not fixed traits but stable states. The stability and the endurance of these states in individuals comes not solely from fixed genetic qualities or characteristics of human beings; nor, for that matter, does it come solely from the stable, fixed demands of environmental circumstances. Rather, stable and enduring patterns of human individuality arise from consistent patterns of transaction between the individual and his or her environment. Leona Tyler calls these patterns of transaction possibility-processing structures.

We can use the general term possibility-processing structures to cover all of these concepts having to do with the ways in which the person controls the selection of perceptions, activities, and learning situations. Any individual can carry out, simultaneously or successively, only a small fraction of the acts for which his sense organs, nervous system, and muscles equip him. Only a small fraction of the energies constantly bombarding the individual can be responded to. If from moment to moment a person had to be aware of all of these stimulating energies, all of these possible responses, life would be unbearably complicated and confusing. The reason that one can proceed in most situations to act sensibly without having to make hundreds of conscious choices is that one develops organized ways of automatically processing most of the kinds of information encountered. In computer terms, one does what one is “programmed” to do. Much of the programming is the same for all or most of the human race; much is imposed by the structure of particular culture and subcultures. But in addition there are programs unique to individuals, and these are fundamental to psychological individuality (Tyler, 1978, pp. 106–107).

The concept of possibility-processing structure gives central importance to the role of individual choice in decision making. The way we process the possibilities of each new emerging event determines the range of choices and decisions we see. The choices and decisions we make, to some extent, determine the events we live through, and these events influence our future choices. Thus, people create themselves through their choice of the actual occasions they live through. In Tyler’s words, to some degree we write our own “programs.” Human individuality results from the pattern or “program” created by our choices and their consequences.

Learning Styles as Possibility-Processing Structures

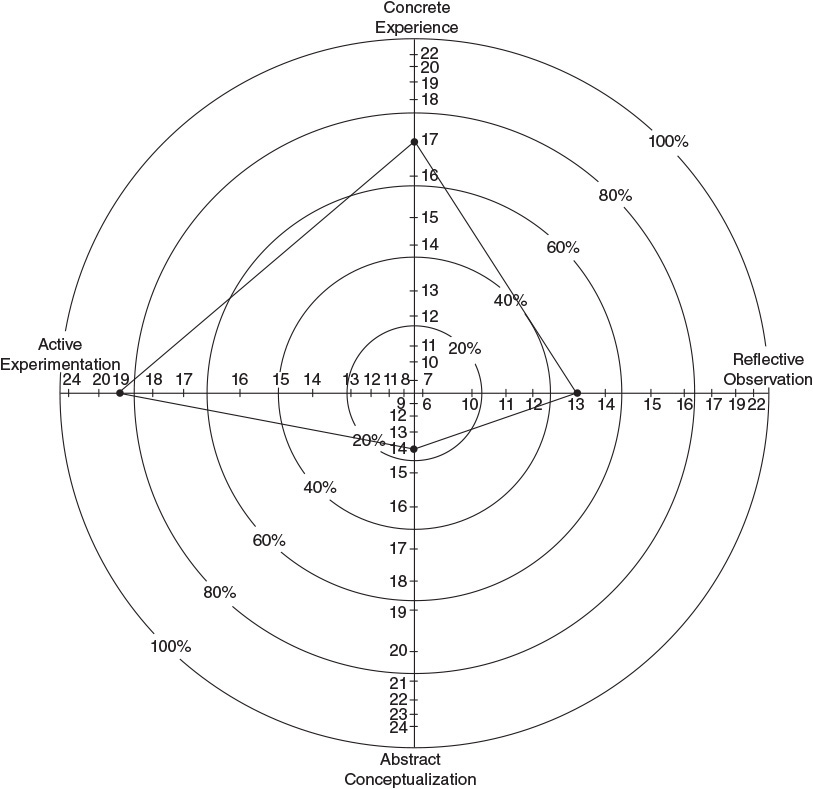

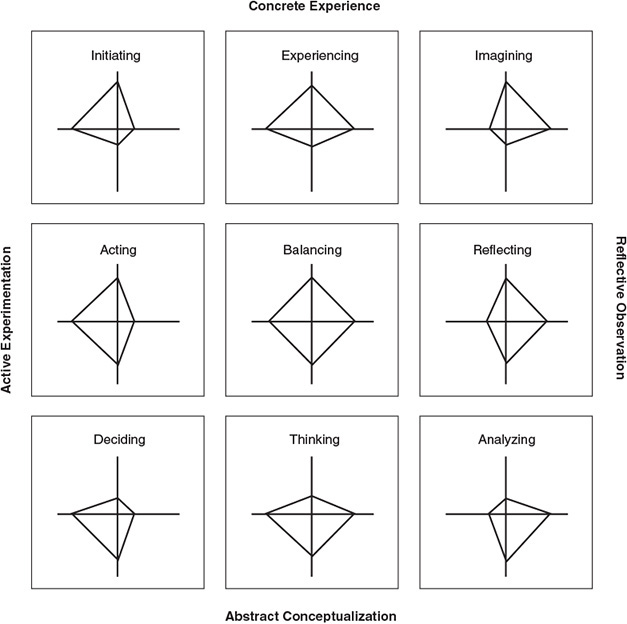

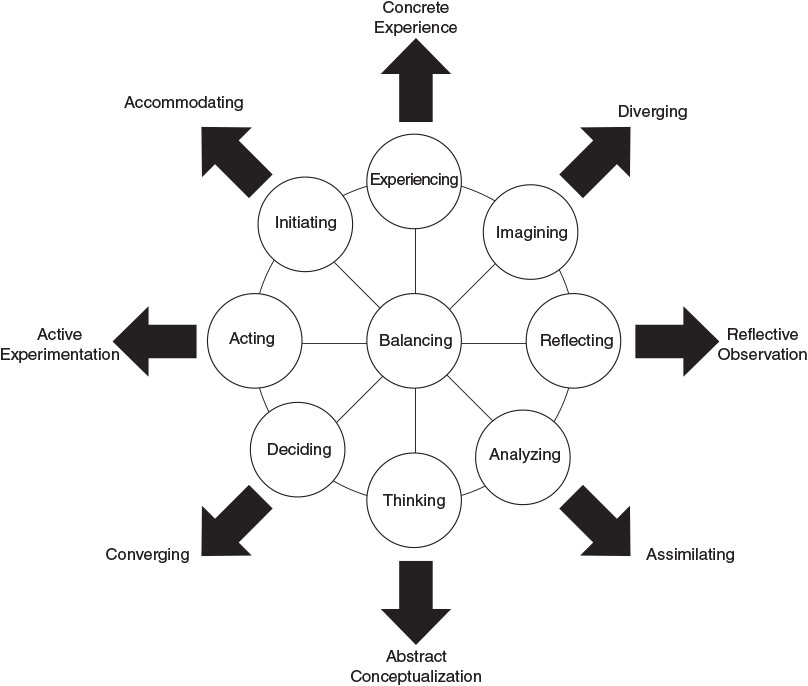

The complex structure of learning allows for the emergence of individual, unique possibility-processing structures or styles of learning. Through their choices of experience, people program themselves to grasp reality through varying degrees of emphasis on apprehension or comprehension. Similarly, they program themselves to transform these prehensions via extension and/or intention. This self-programming conditioned by experience determines the extent to which the person emphasizes the four modes of the learning process: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2 for examples).

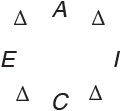

To illustrate the variety and complexity of the learning process, let us examine in some detail how these processes unfold in the specific situation of playing and learning the game of pool. Pool players, be they novice or expert, use a variety of learning strategies in the course of their play. In some of these strategies, we see very clearly the four basic elemental forms of learning: AΔI, apprehension transformed by intention; AΔE, apprehension transformed by extension; CΔI, comprehension transformed by intention; and CΔE, comprehension transformed by extension. In addition, we also see higher-order combinations of these basic elemental forms—for example, AΔIΔC, apprehension linked via intentional transformation with comprehension.

![]() CΔE—A very common learning strategy in playing pool is comprehension transformed by extension. Here the pool player uses an abstract model or theory about how the ball will travel when it is struck with the cue to predict a course for the cue ball such that it will strike the object ball into the pocket. The player may explicitly recall basic physics, that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, and may actually measure out on the table the corresponding angles necessary. This strategy emphasizes the abstract conceptualization and active experimentation modes of the learning process.

CΔE—A very common learning strategy in playing pool is comprehension transformed by extension. Here the pool player uses an abstract model or theory about how the ball will travel when it is struck with the cue to predict a course for the cue ball such that it will strike the object ball into the pocket. The player may explicitly recall basic physics, that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, and may actually measure out on the table the corresponding angles necessary. This strategy emphasizes the abstract conceptualization and active experimentation modes of the learning process.

![]() AΔE—Another common approach is apprehension transformed by extension. This learning strategy does not rely on a theoretical model about how the cue ball and object ball will travel, but rather focuses on the concrete position of the balls on the table. The player relies on a global intuitive feel of the situation. In this situation, the player often seems to be making minor adjustments before hitting the ball, with the criteria for these adjustments being not some theoretical calculation but the finding of a position that “feels right.” Here, concrete experience and active experimentation are the dominant learning modes used.

AΔE—Another common approach is apprehension transformed by extension. This learning strategy does not rely on a theoretical model about how the cue ball and object ball will travel, but rather focuses on the concrete position of the balls on the table. The player relies on a global intuitive feel of the situation. In this situation, the player often seems to be making minor adjustments before hitting the ball, with the criteria for these adjustments being not some theoretical calculation but the finding of a position that “feels right.” Here, concrete experience and active experimentation are the dominant learning modes used.

![]() AΔI—Since pool is an active game, learning through intentional transformations is less obvious. Intentional transformation of apprehensions may take the form of watching one’s opponent or partner as he or she shoots, or of reflecting on the course of one’s own shots. Here, one learns in fairly concrete ways by modeling or picking up hints from someone else’s approach to the game or trying to do again what one did on the last shot. This strategy relies on reflective observation and concrete experience.

AΔI—Since pool is an active game, learning through intentional transformations is less obvious. Intentional transformation of apprehensions may take the form of watching one’s opponent or partner as he or she shoots, or of reflecting on the course of one’s own shots. Here, one learns in fairly concrete ways by modeling or picking up hints from someone else’s approach to the game or trying to do again what one did on the last shot. This strategy relies on reflective observation and concrete experience.

![]() CΔI—Intentional transformation of comprehensions, on the other hand, is a kind of inductive model-building process relying on abstract conceptualization and reflective observation. For example, one might try to understand the consequences of applying “English” to the ball by compiling and organizing into laws one’s observations of the various attempts by oneself and others.

CΔI—Intentional transformation of comprehensions, on the other hand, is a kind of inductive model-building process relying on abstract conceptualization and reflective observation. For example, one might try to understand the consequences of applying “English” to the ball by compiling and organizing into laws one’s observations of the various attempts by oneself and others.

All the learning strategies above taken separately have a certain incompleteness to them. Although one can analytically identify certain learning achievements in each of the four elementary learning modes just described, more powerful and adaptive forms of learning emerge when these strategies are used in combination. For example, if the theory of “English” that I develop through comprehension transformed by intension—CΔI—is combined with the empirical testing of hypotheses derived from that theory—CΔE—I have developed a way of checking the validity of my inductive process that uses three of the four modes of the learning process: reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation (IΔCΔE). Similarly, if I combine these hypotheses about the effects of “English” (CΔE) with my concrete feel of the situation (AΔE), these abstract ideas about how to impart English to the ball will be translated into the appropriate motor and perceptual behavior: I will increase my confidence that my hypotheses about “English” have in fact been adequately tested; that is, I did actually hit the ball the way I had planned to (CΔEΔA). Thus, these pairwise combinations of elementary learning strategies that share a common prehension or transformation mode produce a somewhat higher level of learning beyond the elementary forms. This second-order learning includes not only some goal-directed behavior, such as deriving a hypothesis from a theory or garnering observations from a specific experience, but also some process for testing out how adequately that goal-directed activity has been carried out. This second-order feedback loop stimulates the development of the learning modality in common between the two elementary learning modes. Thus, in the example just cited, the linking of apprehension and comprehension through extension allows for increasing sophistication in extensional learning skills. When apprehension/extension (AΔE) is combined with apprehension/intention (AΔI), a similar result occurs. That is, when I relax and hit the ball (AΔE) and then watch carefully where it goes (AΔI), my awareness of the situation becomes more sophisticated and higher-level (EΔAΔI).

The combination of all four of the elementary learning forms produces the highest level of learning, emphasizing and developing all four modes of the learning process. Here, the specialized achievements of the four elementary learning strategies combine in a unified adaptive process. Here our pool player observes the events around him/her (AΔI), integrates these into theories (IΔC) from which he or she derives hypotheses, which are then tested out in action (CΔE), creating new events and experiences (EΔA). Any new observations are used to modify theories and adjust action, thereby creating an increasingly sophisticated adaptive process that is progressively attuned to the requirement of the game:

If you were to analyze your own approach to learning the game of pool or to spend some time observing players at your local pool hall, I suspect you would find that very few people follow this highest level of learning much of the time. Some people just step up and hit the ball without bothering to look very carefully at where their shot went unless it went in the pocket. Others seem to go through a great deal of analysis and measurement but seem a bit hesitant on the execution. Thus there seem to be distinctive styles or strategies for learning and playing the game. Yet even when people have distinctive styles that rely heavily on one of the elementary learning strategies, there are occasions in their learning process when they rely on other of the elementary forms and combine these with their preferred orientation into the second and third orders of learning.

Individual styles of learning are complex and not easily reducible into simple typologies—a point to bear in mind as we attempt to describe general patterns of individuality in learning. Perhaps the greatest contribution of cognitive-style research has been the documentation of the diversity and complexity of cognitive processes and their manifestation in behavior. Three important dimensions of diversity have been identified:

![]() Within any single theoretical dimension of cognitive functioning, it is possible to identify consistent subtypes. For example, it appears that the dimension of cognitive complexity/simplicity can be further divided into at least three distinct subtypes: the tendency to judge events with few variables versus many; the tendency to make fine versus gross distinctions on a given dimension; and the tendency to prefer order and structure versus tolerance of ambiguity (Vannoy, 1965).

Within any single theoretical dimension of cognitive functioning, it is possible to identify consistent subtypes. For example, it appears that the dimension of cognitive complexity/simplicity can be further divided into at least three distinct subtypes: the tendency to judge events with few variables versus many; the tendency to make fine versus gross distinctions on a given dimension; and the tendency to prefer order and structure versus tolerance of ambiguity (Vannoy, 1965).

![]() Cognitive functioning will vary among people as a function of the area of content it is focused on, the so-called cognitive domain. Thus, a person may be concrete in his interaction with people and abstract in his work (Stabell, 1973), or children will analyze and classify persons differently from nations (Signell, 1966).

Cognitive functioning will vary among people as a function of the area of content it is focused on, the so-called cognitive domain. Thus, a person may be concrete in his interaction with people and abstract in his work (Stabell, 1973), or children will analyze and classify persons differently from nations (Signell, 1966).

![]() Cultural experience plays a major role in the development and expression of cognitive functioning. Lessor (1976) has shown consistent differences in thinking style across different American ethnic groups; Witkin (1976) has shown differences in global and abstract functioning in different cultures; and Bruner et al. (1966) have shown differences in the rate and direction of cognitive development across cultures. Although the evidence is not conclusive, it would appear that these cultural differences in cognition, in Michael Cole’s words, “reside more in the situations to which cognitive processes are applied than in the existence of a process in one cultural group and its absence in another” (1971, p. 233). Thus, Cole found that African Kpelle tribesmen were skillful at measuring rice but not at measuring distance. Similarly, Wober (1967) found that Nigerians function more analytically than Americans when measured by a test that emphasizes proprioceptive cues, whereas they were less skilled at visual analysis.

Cultural experience plays a major role in the development and expression of cognitive functioning. Lessor (1976) has shown consistent differences in thinking style across different American ethnic groups; Witkin (1976) has shown differences in global and abstract functioning in different cultures; and Bruner et al. (1966) have shown differences in the rate and direction of cognitive development across cultures. Although the evidence is not conclusive, it would appear that these cultural differences in cognition, in Michael Cole’s words, “reside more in the situations to which cognitive processes are applied than in the existence of a process in one cultural group and its absence in another” (1971, p. 233). Thus, Cole found that African Kpelle tribesmen were skillful at measuring rice but not at measuring distance. Similarly, Wober (1967) found that Nigerians function more analytically than Americans when measured by a test that emphasizes proprioceptive cues, whereas they were less skilled at visual analysis.

Our investigation of learning styles will begin with an examination of generalized differences in learning orientations based on the degree to which people emphasize the four modes of the learning process as measured by a self-report test called the Learning Style Inventory. From these investigations we will draw a clearer picture of the programs or patterns of behavior that characterize the four elementary forms of learning. With these patterns as a rough map of the terrain of individuality in learning, the next chapter will examine the relationships among these styles of learning and the structure of knowledge. Chapter 6 will consider the higher levels of learning and the relation between learning and development.

Assessing Individual Learning Styles: The Learning Style Inventory

To assess individual orientations toward learning, the Learning Style Inventory (LSI) was created. The development of this instrument was guided by four design objectives: First, the test should be constructed in such a way that people would respond to it in somewhat the same way as they would a learning situation; that is, it should require one to resolve the opposing tensions between abstract-concrete and active-reflective orientations. In technical testing terms, we were seeking a test that was both normative, allowing comparisons between individuals in their relative emphasis on a given learning mode such as abstract conceptualization, and ipsative, allowing comparisons within individuals on their relative emphasis on the four learning modes—for instance, whether they emphasized abstract conceptualization more than the other three learning modes in their individual approach to learning.

Second, a self-description format was chosen for the inventory, since the notion of possibility-processing structure relies heavily on conscious choice and decision. It was felt that self-image descriptions might be more powerful determinants of behavioral choices and decisions than would performance tests. Third, the inventory was constructed with the hope that it would prove to be valid—that the measures of learning styles would predict behavior in a way that was consistent with the theory of experiential learning. A final consideration was a practical one. The test should be brief and straightforward, so that in addition to research uses, it could be used as a means of discussing the learning process with those tested and giving them feedback on their own learning styles.

The final form of the test is a nine-item self-description questionnaire. Each item asks the respondent to rank-order four words in a way that best describes his or her learning style. One word in each item corresponds to one of the four learning modes—concrete experience (sample word, feeling), reflective observation (watching), abstract conceptualization (thinking), and active experimentation (doing). The LSI measures a person’s relative emphasis on each of the four modes of the learning process—concrete experience (CE), reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC), and active experimentation (AE)—plus two combination scores that indicate the extent to which the person emphasizes abstractness over concreteness (AC-CE) and the extent to which the person emphasizes action over reflection (AE-RO). The four basic learning modes are defined as follows:

![]() An orientation toward concrete experience focuses on being involved in experiences and dealing with immediate human situations in a personal way. It emphasizes feeling as opposed to thinking; a concern with the uniqueness and complexity of present reality as opposed to theories and generalizations; an intuitive, “artistic” approach as opposed to the systematic, scientific approach to problems. People with concrete-experience orientation enjoy and are good at relating to others. They are often good intuitive decision makers and function well in unstructured situations. The person with this orientation values relating to people and being involved in real situations, and has an open-minded approach to life.

An orientation toward concrete experience focuses on being involved in experiences and dealing with immediate human situations in a personal way. It emphasizes feeling as opposed to thinking; a concern with the uniqueness and complexity of present reality as opposed to theories and generalizations; an intuitive, “artistic” approach as opposed to the systematic, scientific approach to problems. People with concrete-experience orientation enjoy and are good at relating to others. They are often good intuitive decision makers and function well in unstructured situations. The person with this orientation values relating to people and being involved in real situations, and has an open-minded approach to life.

![]() An orientation toward reflective observation focuses on understanding the meaning of ideas and situations by carefully observing and impartially describing them. It emphasizes understanding as opposed to practical application; a concern with what is true or how things happen as opposed to what will work; an emphasis on reflection as opposed to action. People with a reflective orientation enjoy intuiting the meaning of situations and ideas and are good at seeing their implications. They are good at looking at things from different perspectives and at appreciating different points of view. They like to rely on their own thoughts and feelings to form opinions. People with this orientation value patience, impartiality, and considered, thoughtful judgment.

An orientation toward reflective observation focuses on understanding the meaning of ideas and situations by carefully observing and impartially describing them. It emphasizes understanding as opposed to practical application; a concern with what is true or how things happen as opposed to what will work; an emphasis on reflection as opposed to action. People with a reflective orientation enjoy intuiting the meaning of situations and ideas and are good at seeing their implications. They are good at looking at things from different perspectives and at appreciating different points of view. They like to rely on their own thoughts and feelings to form opinions. People with this orientation value patience, impartiality, and considered, thoughtful judgment.

![]() An orientation toward abstract conceptualization focuses on using logic, ideas, and concepts. It emphasizes thinking as opposed to feeling; a concern with building general theories as opposed to intuitively understanding unique, specific areas; a scientific as opposed to an artistic approach to problems. A person with an abstract-conceptual orientation enjoys and is good at systematic planning, manipulation of abstract symbols, and quantitative analysis. People with this orientation value precision, the rigor and discipline of analyzing ideas, and the aesthetic quality of a neat conceptual system.

An orientation toward abstract conceptualization focuses on using logic, ideas, and concepts. It emphasizes thinking as opposed to feeling; a concern with building general theories as opposed to intuitively understanding unique, specific areas; a scientific as opposed to an artistic approach to problems. A person with an abstract-conceptual orientation enjoys and is good at systematic planning, manipulation of abstract symbols, and quantitative analysis. People with this orientation value precision, the rigor and discipline of analyzing ideas, and the aesthetic quality of a neat conceptual system.

![]() An orientation toward active experimentation focuses on actively influencing people and changing situations. It emphasizes practical applications as opposed to reflective understanding; a pragmatic concern with what works as opposed to what is absolute truth; an emphasis on doing as opposed to observing. People with an active-experimentation orientation enjoy and are good at getting things accomplished. They are willing to take some risk in order to achieve their objectives. They also value having an influence on the environment around them and like to see results.

An orientation toward active experimentation focuses on actively influencing people and changing situations. It emphasizes practical applications as opposed to reflective understanding; a pragmatic concern with what works as opposed to what is absolute truth; an emphasis on doing as opposed to observing. People with an active-experimentation orientation enjoy and are good at getting things accomplished. They are willing to take some risk in order to achieve their objectives. They also value having an influence on the environment around them and like to see results.

Norms for scores on the LSI were developed from a sample of 1,933 men and women ranging in age from 18 to 60 and representing a wide variety of occupations. These norms, along with reliability and validity data for the LSI, are reported in detail elsewhere (Kolb, 1976, 1981). The following sample LSI profiles are included along with the respondents’ self-descriptions to illustrate the kind of self-assessment information generated by the inventory. The first profile is that of a 20-year-old female social worker currently completing a graduate degree in social work (see Figure 4.1). Her high scores on concrete experience and active experimentation are evident not only in the content of the following excerpts from her self-analysis but also in the way the analysis is written, with its strong feeling tone:

The Learning Style exercise and assignment had a tremendous effect on me, forcing me to take stock of my standard learning and problem solving pattern. And, obviously, these patterns more or less represent my general life patterns and attitudes. In the past, I have noted my methods of handling specific problems, but the assignment really pulled it all together, which was more than a little terrifying. . . . [She describes her recent experience in choosing an apartment.]

Those are the specifics. I can recall many other examples where my learning and problem solving style was exactly the same. In fact, I’m writing this paper right now, twenty minutes after class, as a direct result of my poor score on the paper just returned to me. If I sat and analyzed what it meant to receive a poor mark, I would become too upset. I had to do something about it, to fix it, so I immediately went home and sat down to write a good paper to prove I could do better.

The general process is clear: When I first become emotionally concerned with a problem, the only way I can see to relieve the worry is to jump into action, “solving” the problem as quickly as possible. It’s too hard, too hurting, to sit and think and analyze. When a problem touches me on a gut level, be it a love affair or a beautiful pair of shoes in a store window, I jump to concrete action; I accommodate.

During the aforementioned apartment search, as during most of my escapades, a little voice in the back of my head knew what was going on and warned and cautioned me. Yet I proceeded just the same. It’s as if my process is compulsive and inevitable; I feel it to be almost beyond any conscious control on my part.

I realize that my problem solving process is not 100% destructive. My instincts are often very good, and I’m just as likely to make the right decision as not, based on my experience. In fact, this same compulsive need to act has led me into many beautiful and exciting adventures which I wouldn’t have missed for the world. What frightens me is my apparent inability to try out other problem solving techniques.

My accommodator style [see below, under “Characteristics of the Basic Learning Styles”] most concerns me in the context of professional situations. When working with a client, I tend to promote and encourage action choices or solutions before we have fully analyzed the problem at hand; it breaks my heart to see a client suffer, so I want to relieve his or her pain with the same medicine I use on myself. I am always trying to slow down, to check and double check, to consider a wide range of options. But on the other hand, my action instincts have many times procured immediate vital services for a client, while my more reflective colleagues were still putzing around on paper.

I’m also concerned about the effect of this style on my life plans. I’ve jumped from major to major in college, and recently from career to career, without much careful, consistent reflection and analysis. Again, the benefits are a variety of rich experiences at a relatively young age; I have never felt stagnant or bored. The consequences are that, up to now, I’ve never allowed myself to realize potential in any field. I am presently trying very hard to break that pattern. I am focusing, to the best of my ability, on social work, both academic and practical. I’m attempting to discover the joys of thoroughness. It’s not easy. I’m tempted to jump around like a little flea. . . .

The process of sorting my thoughts for this paper has meant a great deal to me. It took me an hour to sort it out. That may not be much for most people, but a concentrated hour of attempting to calmly and reflectively sort my thoughts represents a minor miracle for me! And I must admit that it feels good.

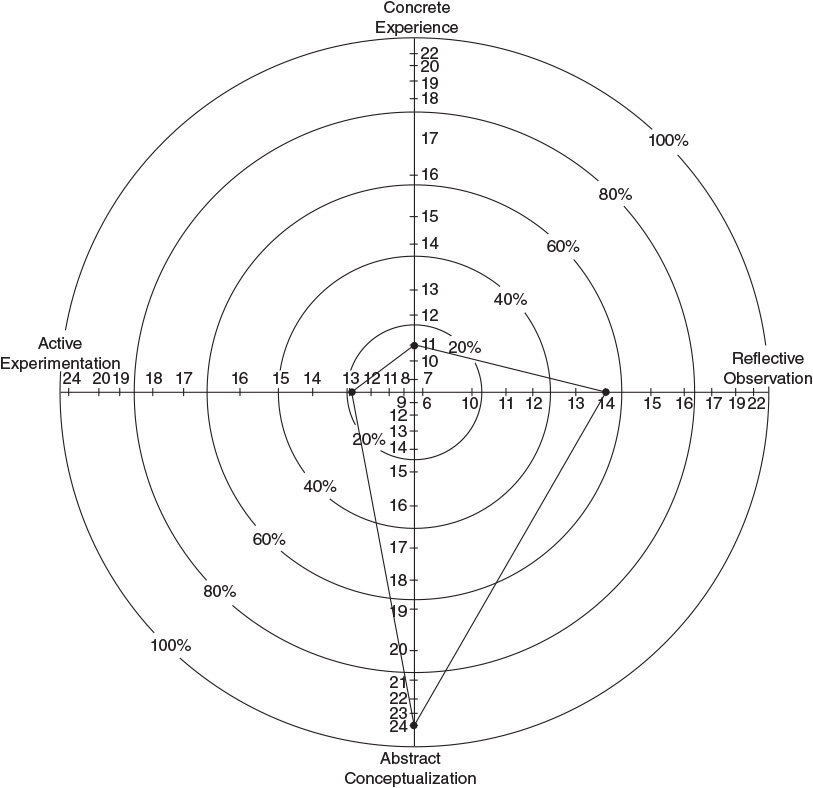

The second example is a very different one. It is from a 32-year-old M.B.A. student (see Figure 4.2). This man’s high scores on abstract conceptualization and reflective observation are reflected in a self-interpretation report that is more formal and academic in its tone. In addition, he describes his difficulties in valuing and learning from the experiential learning approach taken in the organization behavior course where he completed the LSI. In a rather dramatic way, this case demonstrates the powerful effect that learning styles can have on the learning process and at the same time reminds us that experiential learning techniques per se are not preferred by everyone:

“They, assimilators [see below], are often frustrated and benefit little from unstructured ‘discover’ learning approaches such as exercises and simulations.” Falling onto the extreme edge of the assimilator category, I, too, have experienced frustration with the experiential learning approach and much of the content of the course to date. This first conceptual paper will briefly describe my learning style, recount some of my experiences in the course, relate my feelings, present my intellectual reactions to those experiences and feelings, and outline my expected future course of action.

Since the learning process is a dynamic, circular one of building on past experience and learning, some description of my background is needed to understand my learning style preference. The Learning Styles Inventory very clearly identified my assimilator predisposition. Both concrete experience and active experimentation scores were inside the twentieth percentile circle. Reflective observation was in the middle range, while abstract conceptualization fell on the outer circle. This result corresponds well with my formal educational and professional experience. Typically, both mathematicians and economists are assimilators, drawing on theoretical models to describe reality. My degrees in these areas reflect my strength in and affinity for that style of learning. Kolb reports that members of the research and planning departments of organizations tend to be the most assimilative group. Prior to entering the M.B.A. program, I had spent two years in such a capacity, leaving __________ college as Associate Director of Institutional Research and Planning.

Entering the organizational behavior class, I anticipated difficulty, but did not anticipate the wholesale assault on my value system which I encountered. Detailing those incidents and my reactions comprises the body of this essay. Prior to describing concrete situations, I need to present my definition of concrete and active as they apply to learning. Basically, I propose to generalize from the physical definitions to include those activities of the mind which are active and concrete, rather than passive and imprecise. For example, much of the active part of active listening is a mental, rather than a physical, activity. Similarly, for me, active participation in a novel, textbook, or journal article is more “active” than engaging in typical sporting activities. To view my learning as balanced, rather than ivory-towerish, one must surmount what economists term the “fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” Cerebral as well as sensual participation in life can be concrete and active.

Experiences with classmates, instructors, and the texts have all contributed to my feelings of isolation, defensiveness, and frustration. During my group’s first discussion session I expressed my distaste for experiential learning. I noted that it seemed to be the opposite of normal science or education, where the goal of furthering man’s knowledge required building upon the work and achievements of others, rather than egocentrically assuming that individuals would be able to replicate past acts of genius. I was motivated to get my views on the table so that future discussion on my part would be understood in the proper light. Unwittingly, I was combatting what Argyris terms “double loop learning.” I was immediately questioning the rules of the game by putting my views forward.

Reaction by some other members of the group was swift and harsh. Replies such as, “You can’t learn anything from books,” and “Books are irrelevant to business, you learn by doing,” shocked me. Coming from an institution (___________ College) where life revolved almost entirely around intellectual activities, I was surprised to find that students at an apparently similar school possessed anti-intellectual attitudes.

Our group leader reported this discussion as, “One of our members said that he preferred passive learning, had gone to a school where experiential learning was used, and did not like it.” The whole group’s reaction was surprise. I felt embarrassed and misunderstood, wanted to defend my views and straighten out the group leader. Feelings of isolation and serious questioning of my reasons for being in business school followed that session.

During the second group session, a number of our group members discussed the Learning Styles Inventory. One member questioned the validity of the measurement and what it really measured. I presented my views on inductive versus deductive reasoning and the difficulty of constructing an index which is unidimensional. One group member remarked, “I never know what he’s talking about,” leading to snickers from the group. Score crushed ego and feelings a third time.

The physical placement of students on the Learning Styles Inventory grid in the lounge further confirmed my feelings of isolation. From my perspective, four students were extreme assimilators, eight others were assimilators near the center, ten were convergers, twelve were divergers, and twenty were accommodators. The four members of our group discussed the advantages and disadvantages of assimilation as a learning style, questioned the realism of our goals in management vis-á-vis our learning orientation, and related the LSI to our majors and computer programming. I felt a sense of community and cohesion forming in the group. In particular, a lawyer and I confirmed our commonality of vision.

This activity did result in constructive reflection on my part. It appears to me that people under stress or feeling isolated seek others with similar feelings for security. In addition, the experience spurred me to look in the reader for more information. The last article presented findings on the distribution of academics majors on the LSI grid which satisfied some of my curiousity about the applicability of the inventory. . . .

Evidence for the Structure of Learning

The structural model of learning developed in the preceding chapter postulates two fundamental dimensions of the learning process, each describing basic adaptive processes standing in dialectical opposition. The prehension dimension opposes the process of apprehension and an orientation toward concrete experience against the comprehension process and an orientation toward abstract conceptualization. The transformation dimension opposes the process of intention and reflective observation against the process of extension and active experimentation. We have emphasized that these dimensions are not unitary theoretically, such that a high score on one orientation would automatically imply a low score on its opposite, but rather that they are dialectically opposed, implying that a higher-order synthesis of opposing orientations makes highly developed strengths in opposing orientations possible. If this reasoning is applied to scores on the Learning Style Inventory, we would predict a moderate (but not perfect) negative relation between abstract conceptualization and concrete experience and a similar negative relation between active experimentation and reflective observation. Other correlations should be near zero. Intercorrelations of the scale scores for a sample of 807 people shows this to be the case (see Kolb, 1976, for details). CE and AC were negatively correlated (−.57, p < .001). RO and AE were negatively correlated (−.50, p < .001). Other correlations were low but significant because of the large sample size (CE) with RO = .13, RO with AC = −.19, AC with AE = −.12, and AE with CE = −.02). All but the last are significant (p < .001). As a result of the intercorrelations, we felt justified in creating two combination scores to measure the abstract/concrete dimension (AE-CE) and active/reflective dimension (AE-RO). With the abstract/concrete dimension, CE correlated −.85 and AC correlated .90. With the active/reflective dimension, AE correlated .85 and RO correlated -.84. Subsequent studies with more limited and specialized populations have shown patterns of correlation similar to those described above. One longitudinal study of changes in learning style during college examined the relationship between the Learning Style Inventory and commonly used instruments designed to measure cognitive development according to Piaget, Kohlberg, Loevinger, and Perry theoretical descriptions of growth. Analyses of the interrelationships of college student performance on these measures found that the concrete/abstract dimension correlated with these measures. The reflective/active dimension did not. For these college students, dimensions of learning and development designed to tap cognitive growth do not reflect movement on the reflective/active dimension. The latter dimension also does not correlate with age at entrance to college for younger or older students, which supports the idea that the two dimensions are independent (Mentkowski and Strait, 1983).

A more rigorous test of these hypothesized relationships requires controlling for the built-in negative correlations in the LSI caused by the forced-ranking procedure and validation of the scales against external criteria. It is possible to control for the “bias” introduced by the forced-choice format of the LSI by using data from a study by Certo and Lamb (1979), who generated 1,000 random responses to the LSI instrument and intercorrelated the resulting scale scores. The resulting correlations measure the magnitude of the inbuilt negative correlations in the LSI. If these correlations are used as the null hypothesis instead of the traditional zero point to test for significance of difference, the hypothesized negative relationships between AC and CE and between AE and RO can be tested with the forced-ranking effect partialed out. Thus, when Certo and Lamb’s random correlations are compared to the empirical correlations obtained from 807 subjects using the formula provided by McNemar (1957, p. 148), both the AC/CE correlations and AE/RO correlations are significantly more negative than the random correlations (random AC/CE = −.26, empirical = −.57, p of difference < .001; random AE/RO = −.35, empirical = −.50, p of difference < .001).

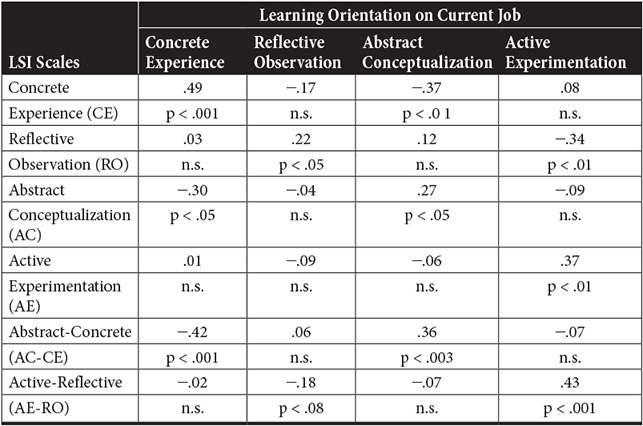

External validation of these negative relationships comes from a recent study by Gypen (1980). He correlated ratings by professional social workers and engineers of the extent to which they were oriented toward each of the four learning modes in their current job with their LSI scores obtained four to six months earlier. Each mode was rated separately on a seven-point scale describing the learning mode in a way that attempted to minimize social-desirability bias. Table 4.1 shows the correlations between the subjects’ LSI scores and self-ratings of their current job orientation. These results provide strong support for the negative relation between concrete experience and abstract conceptualization, and somewhat weaker support for the negative relation between active experimentation and reflective observation. The Gypen study and the “corrected” internal correlations among LSI scales both demonstrate empirical support for the bipolar nature of the experiential learning model that is independent of the forced-ranking method used in the LSI.

Table 4.1 Pearson Correlation Coefficients between the Learning Style Inventory Scales and Ratings of Learning Orientations at Work (N = 58)

Although these data do not prove validity of the structural learning model, they do suggest an analytic heuristic for exploring with the LSI the characteristics of the four elemental forms of knowing proposed by the model (refer to Figure 3.1). If for purposes of analysis we treat the abstract-concrete (AC-CE) and active-reflective (AE-RO) dimensions as negatively related in a unidimensional sense, it is possible to create a two-dimensional map of learning space that can be used to empirically characterize differences in the four elementary forms of knowing: convergence, divergence, assimilation, and accommodation. In so doing, I will save the third dimension for depicting in Chapter 6 the process of development and higher forms of knowing achieved through the dialectic synthesis of action/reflection and abstract/concrete orientations.

Since the AC and CE scales and AE and RO scales are not perfectly negatively correlated, two other types of LSI scores do in fact occur occasionally: those that are highest on AC and CE, and those that are highest on AE and RO. These so-called “mixed” types of people, on the basis of what fragmentary evidence we have, seem to be those who rely on the second- and third-order levels of learning. Thus, through integrative learning experiences, these people have developed styles that emphasize the dialectically opposed orientations. Some support for this argument comes from Rita Weathersby’s study of adult learners at Goddard College (1977). The important point, however, is that the LSI measures differences only in the elementary knowledge orientations, since the forced-ranking format of the inventory precludes integrative responses.

Characteristics of the Basic Learning Styles

In using the analytic heuristic of a two-dimensional-learning-style map, it is proposed that a major source of pattern and coherence in individual styles of learning is the underlying structure of the learning process. Over time, individuals develop unique possibility-processing structures such that the dialectic tensions between the prehension and transformation dimensions are consistently resolved in a characteristic fashion. As a result of our hereditary equipment, our particular past life experience, and the demands of our present environment, most people develop learning styles that emphasize some learning abilities over others. Through socialization experiences in family, school, and work, we come to resolve the conflicts between being active and reflective and between being immediate and analytical in characteristic ways, thus lending to reliance on one of the four basic forms of knowing: divergence, achieved by reliance on apprehension transformed by intention; assimilation, achieved by comprehension transformed by intention; convergence, achieved through extensive transformation of comprehension; and accommodation, achieved through extensive transformation of apprehension.

Some people develop minds that excel at assimilating disparate facts into coherent theories, yet these same people are incapable of or uninterested in deducing hypotheses from the theory. Others are logical geniuses but find it impossible to involve and surrender themselves to an experience. And so on. A mathematician may come to place great emphasis on abstract concepts, whereas a poet may value concrete experience more highly. A manager may be primarily concerned with the active application of ideas, whereas a naturalist may develop his observational skills highly. Each of us in a unique way develops a learning style that has some weak and some strong points. Evidence for the existence of such consistent unique learning styles can be found in the research of Kagan and Witkin (Kagan and Kogan, 1970). They find, in support of Piaget, that there is a general tendency to become more analytic and reflective with age, but that individual rankings within the population tested remain highly stable from early years to adulthood. Similar results have been found for measures of introversion/extraversion. Several longitudinal studies have shown introversion/extraversion to be one of the most stable characteristics of personality from childhood to old age. Although there is a general tendency toward introversion in old age, studies show that people tend to retain their relative ranking throughout their life span (Rubin, 1981). Thus, they seem to develop consistent stable learning or cognitive styles relative to their age mates. The following is a description of the characteristics of the four basic learning styles based on both research and clinical observation of these patterns of LSI scores.

![]() The convergent learning style relies primarily on the dominant learning abilities of abstract conceptualization and active experimentation. The greatest strength of this approach lies in problem solving, decision making, and the practical application of ideas. We have called this learning style the converger because a person with this style seems to do best in situations like conventional intelligence tests, where there is a single correct answer or solution to a question or problem (Torrealba, 1972; Kolb, 1976). In this learning style, knowledge is organized in such a way that through hypothetical-deductive reasoning, it can be focused on specific problems. Liam Hudson’s (1966) research on those with this style of learning (using other measures than the LSI) shows that convergent people are controlled in their expression of emotion. They prefer dealing with technical tasks and problems rather than social and interpersonal issues.

The convergent learning style relies primarily on the dominant learning abilities of abstract conceptualization and active experimentation. The greatest strength of this approach lies in problem solving, decision making, and the practical application of ideas. We have called this learning style the converger because a person with this style seems to do best in situations like conventional intelligence tests, where there is a single correct answer or solution to a question or problem (Torrealba, 1972; Kolb, 1976). In this learning style, knowledge is organized in such a way that through hypothetical-deductive reasoning, it can be focused on specific problems. Liam Hudson’s (1966) research on those with this style of learning (using other measures than the LSI) shows that convergent people are controlled in their expression of emotion. They prefer dealing with technical tasks and problems rather than social and interpersonal issues.

![]() The divergent learning style has the opposite learning strengths from convergence, emphasizing concrete experience and reflective observation. The greatest strength of this orientation lies in imaginative ability and awareness of meaning and values. The primary adaptive ability of divergence is to view concrete situations from many perspectives and to organize many relationships into a meaningful “gestalt.” The emphasis in this orientation is on adaptation by observation rather than action. This style is called diverger because a person of this type performs better in situations that call for generation of alternative ideas and implications, such as a “brainstorming” idea session. Those oriented toward divergence are interested in people and tend to be imaginative and feeling-oriented.

The divergent learning style has the opposite learning strengths from convergence, emphasizing concrete experience and reflective observation. The greatest strength of this orientation lies in imaginative ability and awareness of meaning and values. The primary adaptive ability of divergence is to view concrete situations from many perspectives and to organize many relationships into a meaningful “gestalt.” The emphasis in this orientation is on adaptation by observation rather than action. This style is called diverger because a person of this type performs better in situations that call for generation of alternative ideas and implications, such as a “brainstorming” idea session. Those oriented toward divergence are interested in people and tend to be imaginative and feeling-oriented.

![]() In assimilation, the dominant learning abilities are abstract conceptualization and reflective observation. The greatest strength of this orientation lies in inductive reasoning and the ability to create theoretical models, in assimilating disparate observations into an integrated explanation (Grochow, 1973). As in convergence, this orientation is less focused on people and more concerned with ideas and abstract concepts. Ideas, however, are judged less in this orientation by their practical value. Here, it is more important that the theory be logically sound and precise.

In assimilation, the dominant learning abilities are abstract conceptualization and reflective observation. The greatest strength of this orientation lies in inductive reasoning and the ability to create theoretical models, in assimilating disparate observations into an integrated explanation (Grochow, 1973). As in convergence, this orientation is less focused on people and more concerned with ideas and abstract concepts. Ideas, however, are judged less in this orientation by their practical value. Here, it is more important that the theory be logically sound and precise.

![]() The accommodative learning style has the opposite strengths from assimilation, emphasizing concrete experience and active experimentation. The greatest strength of this orientation lies in doing things, in carrying out plans and tasks and getting involved in new experiences. The adaptive emphasis of this orientation is on opportunity seeking, risk taking, and action. This style is called accommodation because it is best suited for those situations where one must adapt oneself to changing immediate circumstances. In situations where the theory or plans do not fit the facts, those with an accommodative style will most likely discard the plan or theory. (With the opposite learning style, assimilation, one would be more likely to disregard or reexamine the facts.) People with an accommodative orientation tend to solve problems in an intuitive trial-and-error manner (Grochow, 1973), relying heavily on other people for information rather than on their own analytic ability (Stabell, 1973). Those with accommodative learning styles are at ease with people but are sometimes seen as impatient and “pushy.”

The accommodative learning style has the opposite strengths from assimilation, emphasizing concrete experience and active experimentation. The greatest strength of this orientation lies in doing things, in carrying out plans and tasks and getting involved in new experiences. The adaptive emphasis of this orientation is on opportunity seeking, risk taking, and action. This style is called accommodation because it is best suited for those situations where one must adapt oneself to changing immediate circumstances. In situations where the theory or plans do not fit the facts, those with an accommodative style will most likely discard the plan or theory. (With the opposite learning style, assimilation, one would be more likely to disregard or reexamine the facts.) People with an accommodative orientation tend to solve problems in an intuitive trial-and-error manner (Grochow, 1973), relying heavily on other people for information rather than on their own analytic ability (Stabell, 1973). Those with accommodative learning styles are at ease with people but are sometimes seen as impatient and “pushy.”

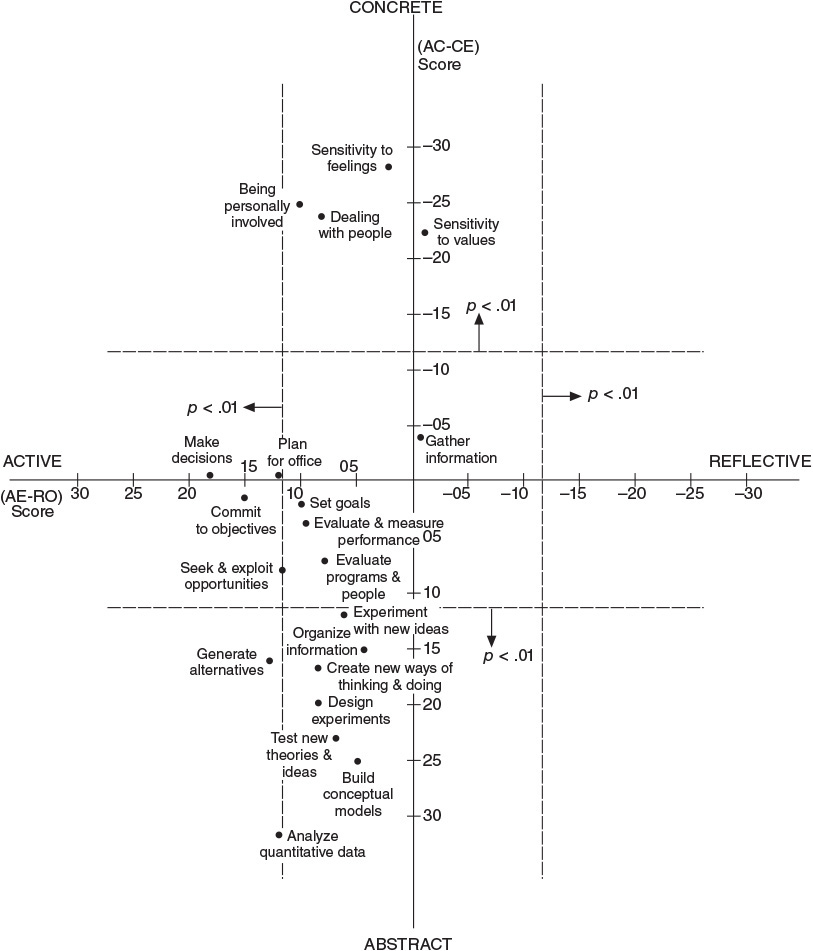

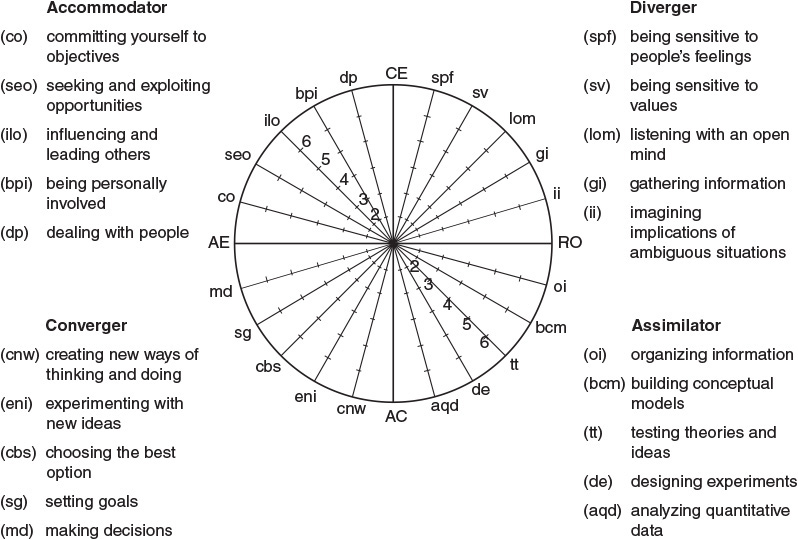

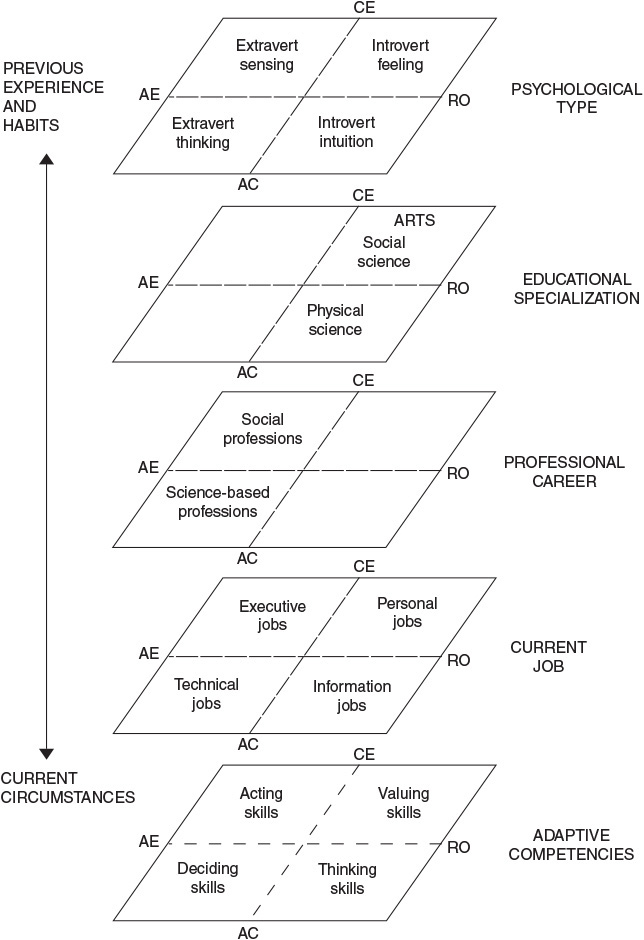

The patterns of behavior associated with these four learning styles are shown consistently at various levels of behavior, from personality type to specific task-oriented skills and behaviors. We will examine these patterns at five such levels: (1) Jungian personality type, (2) early educational specialization, (3) professional career, (4) current job, and (5) adaptive competencies.

Personality Type and Learning Style

We have already acknowledged and examined to some extent the indebtedness of experiential learning theory to Jung’s theory of psychological types. Now we examine more specifically the relations between Jung’s types and the four basic learning styles. In his theory of psychological types, Jung developed a holistic framework for describing differences in human adaptive processes. He began by distinguishing between those people who are oriented toward the external world and those oriented toward the internal world—the distinction between extravert and introvert examined in the last chapter. He then proceeded to identify four basic functions of human adaptation—two describing alternative ways of perceiving, sensation and intuition; and two that describe alternative ways of making judgments about the world, thinking and feeling. In his view, human individuality develops through transactions with the social environment that reward and develop one function over another. He saw that this specialized adaptation is in service of society’s need for specialized skills to meet the differentiated, specialized role demands required for the survival of and development of culture. Jung saw a basic conflict between the specialized psychological orientations required for the development of society and the need for people to develop and express all the psychological functions for their own individual fulfillment. His concept of individuation describes the process whereby people achieve personal integrity through the development and reassertion of the nonexpressed and nondominant functions integrating them with their dominant specialized orientation into a fluid, holistic adaptive process. He describes the conflict between specialized types and individual development in this way:

The natural, instinctive course, like everything in nature, follows the principle of least resistance. One man is rather more gifted here, another there; or, again, adaptation to the early environment of childhood may demand either relatively more restraint and reflection or relatively more sympathy and participation, according to the nature of the parents and other circumstances. Thereby a certain preferential attitude is automatically moulded, which results in different types. Insofar then as every man, as a relatively stable being, possesses all the basic psychological functions, it would be a psychological necessity with a view to perfect adaptation that he should also employ them in equal measure. For there must be a reason why there are different ways of psychological adaptation: Evidently one alone is not sufficient, since the object seems to be only partially comprehended when, for example, it is either merely thought or merely felt. Through a one-sided (typical) attitude there remains a deficit in the resulting psychological adaptation, which accumulates during the course of life; from this deficiency a derangement of adaptation develops, which forces the subject towards a compensation. [Jung, 1923, p. 28]

Thus, his conception of types or styles is identical to that proposed here—a basic but incomplete form of adaptation with the potential for development via integration with other basic types into a fluid, holistic adaptive process.

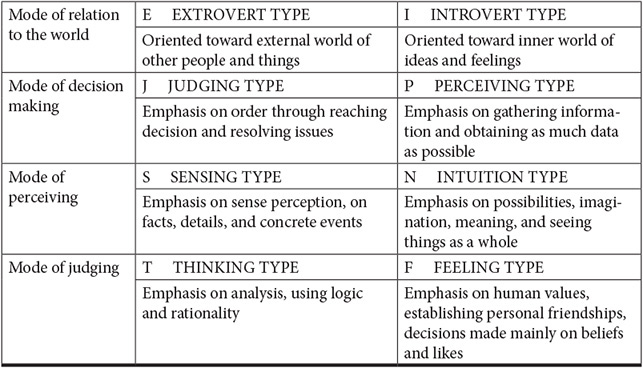

Jung’s typology of psychological types includes four such pairs of dialectically opposed adaptive orientations, describing individuals’ (1) mode of relation to the world via introversion or extroversion, (2) mode of decision making via perception or judgment, (3) preferred way of perceiving via sensing or intuition, and (4) preferred way of judging via thinking or feeling. These opposing orientations are described in Table 4.2.

As was indicated in the preceding chapter, there is a correspondence between the Jungian concepts of introversion and the experiential learning mode of reflective observation via intentional transformation, and between extraversion and active experimentation via extension. In addition, concrete experience and the apprehension process are clearly associated with both the sensing approach to perception and the feeling approach to judging. Abstract conceptualization and the comprehension process, on the other hand, are related to the intuition approach to perceiving and the thinking approach to judging. Predictions about perception and judgment types are difficult to make, since this preference is a second-order one; for instance, if I prefer perception, I could perform it via sensing or intuition. Myers-Briggs states, “In practice the JP preference is a by-product of the choice as to which process, of the two liked best (N over S or T over F), shall govern one’s life” (1962, p. 59).

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is a widely used psychological self-report instrument used to assess people’s orientation toward the Jungian types (Myers, 1962). Correlations between individuals’ scores on the MBTI and the LSI should give some empirical indication of validity of relationships between Jung’s personality types and the learning styles proposed above. Some caution in using such data is appropriate, however. First, both the LSI and the MBTI instruments are based on self-analysis and report. Thus, we are testing whether those who take the two tests agree with our predictions of the similarity between Jung’s concepts and those of experiential learning theory; we are not testing, except by inference, their actual behavior. Second, it is not clear how adequately the MBTI reflects Jung’s theory. In particular, the items in the MBTI introversion/extraversion scale seem to be heavily weighted in favor of the American conception of the dimension mentioned earlier—extraversion as social and interpersonal ease, and introversion as shyness and social awkwardness.

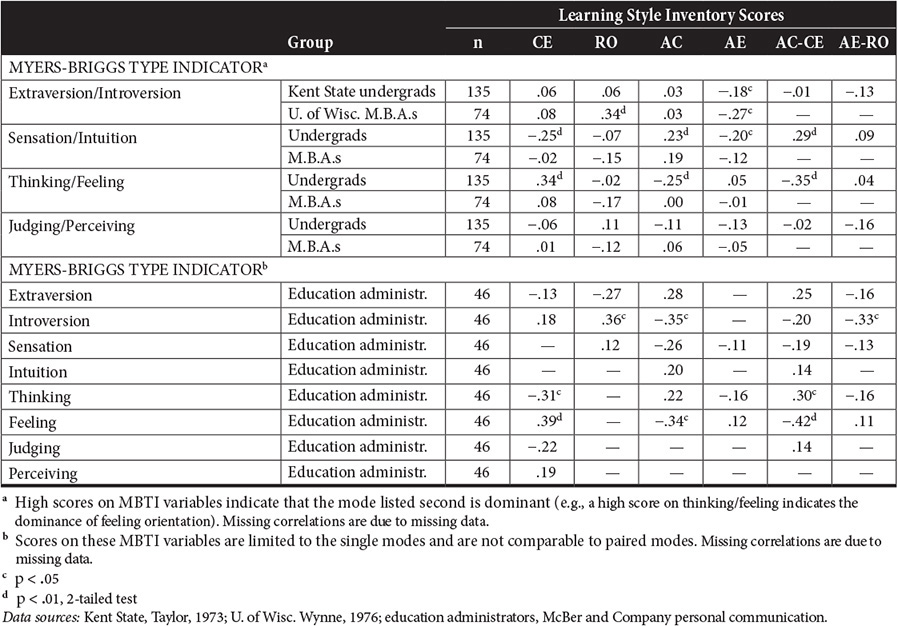

Table 4.3 reports data from three studies by different investigators of three populations: Kent State undergraduates (Taylor, 1973), University of Wisconsin M.B.A.s (Wynne, 1975), and education administrators (McBer and Company, personal communication). The data in Table 4.3 tend to support our hypotheses, but not consistently in all groups: The strongest and most consistent relationships appear to be between concrete/abstract and feeling/thinking and between active/reflective and extravert/introvert.

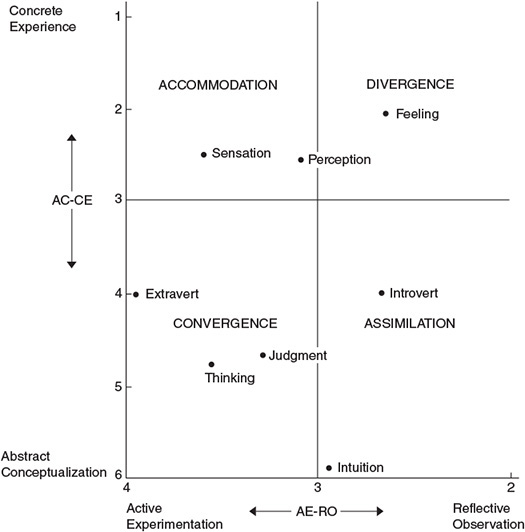

In a more systematic study of 220 managers and M.B.A. students, Margerison and Lewis (1979) investigated the relations between LSI and MBTI scores using the technique of canonical correlation. They found a significant canonical correlation of .45 (p < .01) between the two sets of test scores. When the resulting pattern of psychological types is plotted on the two-dimensional LSI learning-space, relationships between the Jungian types and learning styles become clear and consistent with our predictions (see Figure 4.3). The sensing type is associated with the accommodative learning style, and the intuitive type falls in the assimilative quadrant; the feeling personality type is divergent in learning style, and thinking types are convergent.

Source: Adapted from C. J. Margerison and R. G. Lewis, How Work Preferences Relate to Learning Styles (Bedfordshire, England: Cranfield School of Management, 1979).

Figure 4.3 The Relations between Learning Styles and Jung’s Psychological Types

Regarding introversion and extraversion, Margerison and Lewis conclude:

It is clear that extroverts describe themselves as very active in learning situations. This is to be expected, in that extroverts use their energy to go out into their environment and enjoy contact with people and things. In contrast, introverts are far more reflective as would be expected. However, it is noticeable that both extroverts and introverts prefer involvement in learning situations which are neither excessively detached nor concrete. Clearly, while there is a fair degree of variance, the evidence from our sample illustrates that there is little difference between introverts and extroverts overall in this aspect. The real difference is in their emphasis on a preference for active as against reflective types of role. [Margerison and Lewis, 1979, p. 13]

They also find judgment related to the abstract-conceptualization mode and perception related to concrete experience, but unrelated to action or reflection.

Taken together, these studies suggest that the Jungian personality type associated with the accommodative learning style is extraverted sensing.1 This personality type as described by Myers is remarkably similar to our description of the accommodative learning orientation:

This combination makes the adaptable realist, who good-naturedly accepts and uses the facts around him, whatever they are. He knows what they are, since he notices and remembers more than any other type. He knows what goes on, who wants what, who doesn’t, and usually why. And he does not fight those facts. There is a sort of effortless economy in the way he goes at a situation, never uselessly bucking the line.

Often he can get other people to adapt, too. Being a perceptive type, he looks for the satisfying solution, instead of trying to impose any “should” or “must” of his own, and people generally like him well enough to consider any compromise that he thinks “might work.” He is unprejudiced, open-minded, and usually patient, easygoing and tolerant of everyone (including himself). He enjoys life. He doesn’t get wrought up. Thus he may be very good at easing a tense situation and pulling conflicting factions together. . . .

Being a realist, he gets far more from first-hand experience than from books, is more effective on the job than on written tests, and is doubly effective when he is on familiar ground. Seeing the value of new ideas, theories and possibilities may well come a bit hard, because intuition is his least developed process. [Myers, 1962, p. A5]

1. The procedure for determining types and dominant and auxiliary processes is complicated (see Myers, 1962, pp. 51–62, and Appendix A1–A8). Basically, the choice of introversion or extraversion plus the choice of a single perceiving or judgment mode determines a dominant process.

The divergent learning style is associated with the personality type having introversion and feeling as the dominant process. Here again, Myers’s description of this type fits ours:

An introverted feeling type has as much wealth of feeling as an extraverted feeling type, but uses it differently. He cares more deeply about fewer things. He has his warm side inside (like a fur-lined coat). It is quite as warm but not as obvious; it may hardly show till you get past his reserve. He has, too, a great faithfulness to duty and obligations. He chooses his final values without reference to the judgment of outsiders, and sticks to them with passionate conviction. He finds these inner loyalties and ideals hard to talk about, but they govern his life.

His outer personality is mostly due to his auxiliary process, either S or N, and so is perceptive. He is tolerant, open-minded, understanding, flexible and adaptable (though when one of his inner loyalties is threatened, he will not give an inch). Except for his work’s sake, he has little wish to impress or dominate. The contacts he prizes are with people who understand his values and the goals he is working toward.

He is twice as good when working at a job he believes in, since his feeling for it puts added energy behind his efforts. He wants his work to contribute to something that matters to him, perhaps to human understanding or happiness or health, or perhaps to the perfecting of some product or undertaking. He wants to have a purpose beyond his paycheck, no matter how big the check. He is a perfectionist wherever his feeling is engaged, and is usually happiest at some individual work involving personal values. With high ability, he may be good in literature, art, science, or psychology. [Myers, 1962, p. A4]

The assimilative learning style is characterized by the introverted intuitive type. Myers’s description of this type is similar to the description of the assimilative conceptual orientation but suggests a slightly more practical orientation than we indicate:

The introverted intuitive is the outstanding innovator in the field of ideas, principles and systems of thought. He trusts his own intuitive insight as to the true relationships and meanings of things, regardless of established authority or popularly accepted beliefs. His faith in his inner vision of the possibilities is such that he can remove mountains—and often does. In the process he may drive others, or oppose them, as hard as his own inspirations drive him. Problems only stimulate him; the impossible takes a little longer, but not much.

His outer personality is judging, being mainly due to his auxiliary, either T or F. Thus he backs up his original insight with the determination, perseverance, and enduring purpose of a judging type. He wants his ideas worked out in practice, applied and accepted, and spends any time and effort necessary to that end. [Myers, 1962, p. A8]

The convergent learning style is characterized by the extraverted thinking type. Here, Myers’s description is very consistent with the learning orientation of convergence:

The extraverted thinker uses his thinking to run as much of the world as may be his to run. He has great respect for impersonal truth, thought-out plans, and orderly efficiency. He is analytic, impersonal, objectively critical, and not likely to be convinced by anything but reasoning. He organizes facts, situations, and operations well in advance, and makes a systematic effort to reach his carefully planned objectives on schedule. He believes everybody’s conduct should be governed by logic, and governs his own that way so far as he can.

He lives his life according to a definite set of rules that embody his basic judgments about the world. Any change in his ways requires a conscious change in the rules.

He enjoys being an executive, and puts a great deal of himself into such a job. He likes to decide what ought to be done and to give the requisite orders. He abhors confusion, inefficiency, halfway measures, and anything aimless and ineffective. He can be a crisp disciplinarian, and can fire a person who ought to be fired. [Myers, 1962, p. A1]

Educational Specialization

A major function of education is to shape students’ attitudes and orientations toward learning—to instill positive attitudes toward learning and a thirst for knowledge, and to develop effective learning skills. Early educational experiences shape individual learning styles; we are taught how to learn. Although the early years of education are for the most part generalized, there is an increasing process of specialization that develops beginning in earnest in high school and, for those who continue to college, developing into greater depth in the undergraduate years. This is a specialization in particular realms of social knowledge; thus, we would expect to see relations between people’s learning styles and the early training they received in an educational specialty or discipline.

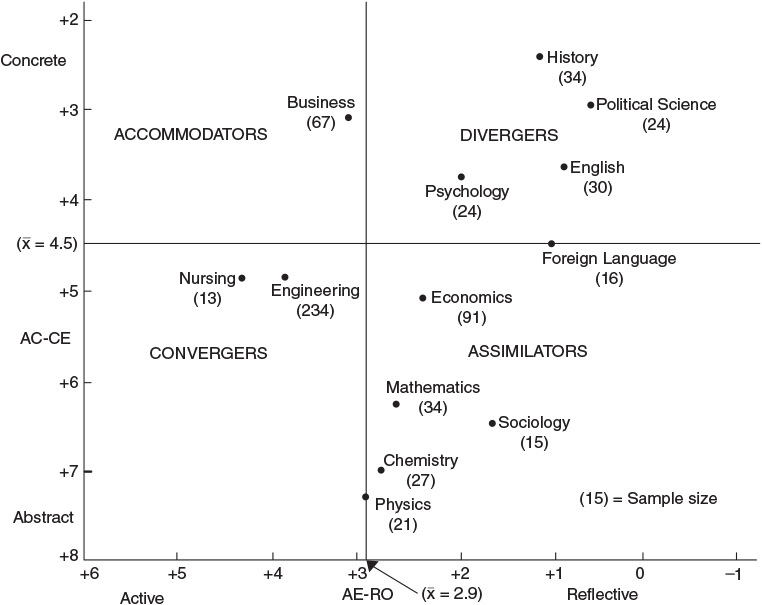

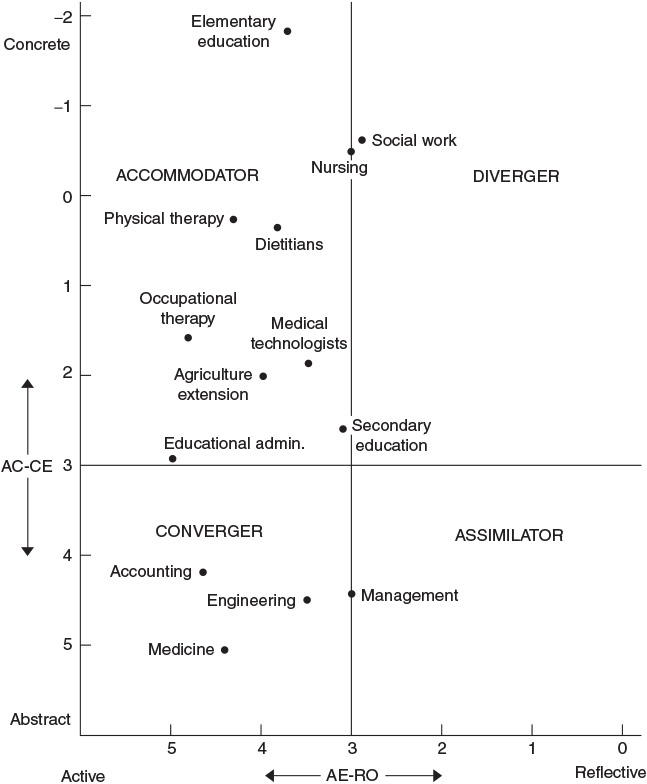

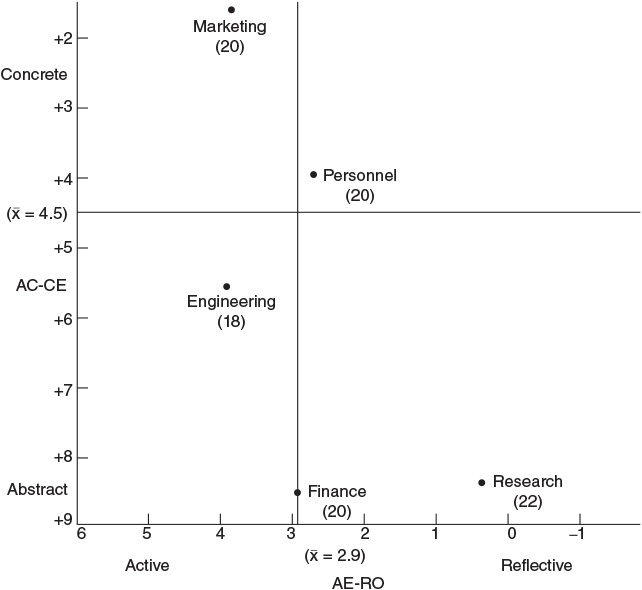

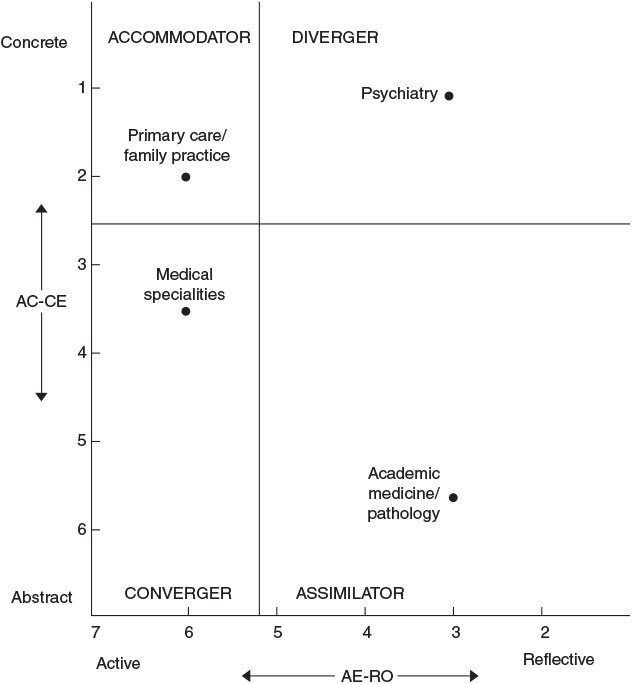

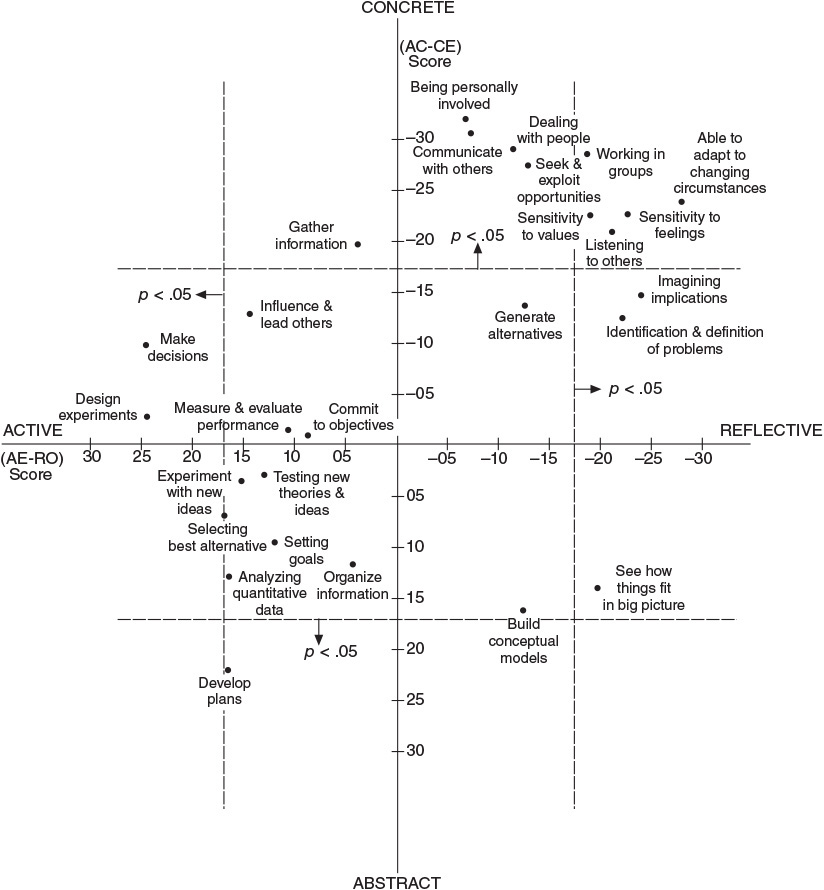

These differences in learning styles can be illustrated graphically by the correspondence between people’s LSI scores and their undergraduate majors. This is done by plotting the average LSI scores for managers in our sample who reported their undergraduate college major; only those majors with more than ten people responding are included (see Figure 4.4). When we examine these people who share a common professional commitment to management, we see that some of the differences in their learning orientations are explained by their early educational specializations in college. Undergraduate business majors tend to have accommodative learning styles; engineers on the average fall in the convergent quadrant; history, English, political science, and psychology majors all have divergent learning styles; mathematics, economics, sociology, and chemistry majors have assimilative learning styles; physics majors are very abstract, falling between the convergent and assimilative quadrants.

Figure 4.4 Average LSI Scores on Active Reflective (AE-RO) and Abstract/Concrete (AC-CE) by Undergraduate College Major

Some cautions are in order in interpreting these data. First, it should be remembered that all the people in the sample are managers or managers-to-be. In addition, most of them have completed or are in graduate school. These two facts should produce learning styles that are somewhat more active and abstract than those of the population at large (as indicated by total sample mean scores on AC-CE and AE-RO of +4.5 and +2.9, respectively). The interaction among career, high level of education, and undergraduate major may produce distinctive learning styles. For example, physicists who are not in industry may be somewhat more reflective than those in this sample. Second, undergraduate majors are described only in the most gross terms. There are many forms of engineering or psychology. A business major at one school can be quite different from one at another.

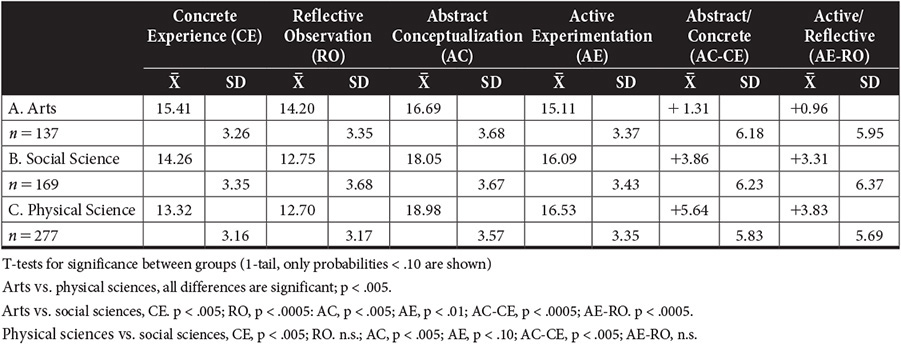

Liam Hudson’s (1966) work on convergent and divergent learning styles predicts that people with undergraduate majors in the arts would be divergers and that those who major in the physical sciences would be convergers. Social-science majors should fall between these two groups. In order to test Hudson’s predictions about the academic specialities of convergers and divergers, the data on undergraduate majors were grouped into three categories: the arts (English, foreign language, education/liberal arts, philosophy, history, and other miscellaneous majors such as music, not recorded in Figure 4.4, total n = 137); social science (psychology, sociology/anthropology, business, economics, political science, n = 169); and physical science (engineering, physics, chemistry, mathematics, and other sciences, such as geology, n = 277). The prediction was that the arts should be concrete and reflective and the physical sciences should be abstract and active, with the social sciences falling in between. The mean scores for these three groups of the six LSI scales are shown in Table 4.4. All these differences are highly significant and in the predicted direction, with the exception that the social sciences and physical sciences do not differ significantly on the active/reflective dimension.