8. Lifelong Learning and Integrative Development

But yield who will to their separation,

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation

As my two eyes make one in sight.

Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes,

Is the deed ever really done

For Heaven and the future’s sakes.

—Robert Frost*

* From “Two Tramps in Mud Time” from THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1936 by Robert Frost. Copyright © 1964 by Lesley Frost Ballantine. Copyright © 1969 by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Reprinted by permission of Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Publishers and Jonathan Cape Ltd.

There has been in recent years a dramatic preoccupation with adult development through the later stages of adult life driven by the huge baby boom demographic passing through them. This emphasis on adult learning and development has been labeled by some a “revolution in human development” (Brim and Kagan, 1980), and indeed, one cannot fail to be impressed by the burgeoning of self-development techniques and activities—from bookstores’ shelves crowded with self-help books to workshops ranging from AA to TA to TM to Zen. Although some see a dangerous current of narcissism and “me” orientation in these developments, I prefer a more positive interpretation—namely, that the dialectic between social specialization and individual integrative fulfillment is itself reaching toward a higher-level synthesis.

The very diversity and intense specialization that threaten to tear us apart are grist for the integrative mill. Modern communication, the mass media, and the other fruits of the information revolution provide an instantaneous cornucopia of fantasies, ideas, perspectives, value conflicts, and crises that challenge and fuel the integrative capacities of us all. We seek to grow and develop because we must do so to survive—as individuals and as a world community. If there is a touch of aggressive selfishness in our search for integrity, it can perhaps be understood as a response to the sometimes overwhelming pressures on us to conform, submit, and comply, to be the object rather than the subject of our life history.

The challenge of lifelong learning is above all a challenge of integrative development. Consider the careers of two great atomic scientists, the American Edward Teller and the Russian Andrei Sakharov, both of whom early in their careers were central in the development of their countries’ nuclear capabilities. Teller went on to become one of our country’s foremost advocates of nuclear power and a strong defense, whereas Sakharov, who gave his country the hydrogen bomb in the 1950s, was stricken by conscience and became a political dissident and a vigorous defender of human rights. Eventually he was banished from Moscow for his protest against the presence of Soviet troops in Afghanistan.

These moral and ethical decisions to promote or reject one’s own inventions, to support or protest against one’s own country, are qualitatively different from the specialized problem-solving activities of the working scientist. As Piaget (1970b) and others (such as Kuhn, 1962) have documented, the historical development of scientific knowledge has been toward increasing specialization, moving from egocentrism to reflection and from phenomenalism to constructivism—in experiential learning terms, from active to reflective and concrete to abstract. Yet the careers of highly successful scientists follow a different path. These people make their specialized abstract-reflective contributions often quite early in their careers. With recognition of their achievements comes a new set of tasks and challenges with active and concrete demands. The Nobel prizewinner must help to shape social policy and to articulate the ethical and value implications of his or her discoveries. The researcher becomes department chairperson and must manage the nurturance of the younger generation. So in this career, and most others as well, the higher levels of responsibility require an integrative perspective that can help shape cultural responses to emergent issues.

The challenges of integrative development are great, and not everyone is successful in meeting them, no matter how intelligent the person or how highly skilled in the professional specialty. In fact, as we have seen in Chapter 7, one’s professional specialization may inhibit development of an integrative perspective. Charles Darwin, in his autobiography, was puzzled about his lost taste for literature, music, and the fine arts, suspecting that this loss was somehow related to his specialization:

My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the highest tastes depend, I cannot conceive. [Darwin, 1958, pp. 138–139]

Several observers have attributed the problems that Jimmy Carter encountered in his presidency to his strong professional identity as a scientist and engineer (Fallows, 1979; Pfaff, 1979) and his difficulties in adapting to the concrete and reflective demands of the presidency (Gypen, 1980). Clark Clifford, who has been a personal consultant and friend to several presidents, said of Carter:

He prided himself on being an engineer and scientist. . . . And every now and then he would say, “Now, as a scientist I would do this.” “As a scientist I would do that.” And he had good scientific training. What scientists do is, they start at A. And they go from A to B and B to C and C to D and D is their goal. And they know that if they just stay on the line, unquestionably they will reach D. I saw that in the President from time to time—that he had sufficient knowledge and experience to know that if he proceeded along a certain line the result would be there. The trouble is, it doesn’t work in the White House. Because it doesn’t take into consideration the House of Representatives, or the Senate of the United States, or the media, or the American people. . . . All these other factors come in. The problems of the President of the United States are not susceptible to scientific treatment. There’s a lot more that goes into it. The fact is you almost have to disregard it. . . . President Carter came into the White House and after a while he got settled and began to feel more comfortable and began to look around for problems to solve. Well, one of them was the Panama Canal. . . . And that is a perfect issue for a president to bring up in the third year of his second term when he can be a statesman. And he can say, “This is right.” And then he doesn’t have to worry about commitments that he has made. But he picked this one out. Now, interestingly enough, he was right. . . . And courageous. But absolutely wrong to bring up at this time. Because he froze a very substantial part of the populace into a position of eternal and permanent enmity, as far as he was concerned. . . . A broader concept on his part of the presidency would have greatly facilitated that decision-making process. Another twenty-two water projects out in the West. . . . He took a look at that and my recollection is he said about 14 of these have no merit and maybe seven or eight have. Well, right about that time out went California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Colorado. [Bill Moyers Journal, 1981, pp. 6–7]

President Carter’s later successes suggest significant progress toward an integrative response to the demands of his office, particularly in achieving a Mideast agreement through personal diplomacy in the Camp David accords. The early years of his term, however, appear to have suffered because of his specialized scientific perspective.

But the challenges of integrative development are not limited to scientists and presidents. A recent Wall Street Journal survey of chief executives asked them to identify the main strengths that determine a manager’s potential for advancement (Allen, 1980). At the head of the list (cited by 36 percent of chief executives from large firms) was integrity, followed by an ability to get along with others and industriousness. Specialized technical experience or education was mentioned by only a few as critical for success. In fact, there are integrative developmental challenges in all occupations, at all occupational levels, and in our private lives as well. Many first-line supervisors, for example, have created personal job definitions that transcend the specialized boundaries of their trade to include the development of younger workers and the building of meaningful community and family relationships.

These challenges become particularly acute in midlife, when as adults we face what Erikson has termed the crisis of generativity or stagnation:

. . . For we are a teaching species. . . . Only man can and must extend his solicitude over the long parallel and overlapping childhoods of numerous offspring united in households and communities. As he transmits the rudiments of hope, will, purpose and skill, he imparts meaning to the child’s bodily experiences; he conveys a logic much beyond the literal meaning of the words he teaches; and he gradually outlines a particular world image and style of citizenship. . . . Once we have grasped this interlocking of the human life stages, we understand that adult man is so constituted as to need to be needed lest he suffer the mental deformation of self-absorption, in which he becomes his own infant and pet. I have, therefore, postulated an instinctual and psychosocial stage of generativity. Parenthood is, for most, the first, and for many, the prime generative encounter; yet the continuation of mankind challenges the generative ingenuity of workers and thinkers of many kinds. [Erikson, 1961, pp. 159–160]

In acceptance of the fact that we are a “teaching species” as well as a “learning species,” a kind of figure/ground reversal takes place at midlife. Our progressive independence from the care of others, our self-oriented pursuit of individual goals, fades from the foreground of our experience to be replaced by a growing concern for the care of others. In the process, other reversals occur as well. In Jung’s terms, the shadow side of personality emerges and claims dominion in consciousness along with the specialized conscious identity of youth. This is a social as well as personal transition, for many forces in the structure of career paths call for personal reassessment and integrative development. For example:

![]() The career cul de sac—careers that provide advancement and opportunity only to a certain point and then require major adaptation and change, e.g., housewife/mother or engineering.

The career cul de sac—careers that provide advancement and opportunity only to a certain point and then require major adaptation and change, e.g., housewife/mother or engineering.

![]() Withdrawal of reward; e.g., up-or-out tenure systems.

Withdrawal of reward; e.g., up-or-out tenure systems.

![]() Withdrawal of opportunity—organizational career paths that have few opportunities for advancement and responsibility at middle and upper levels.

Withdrawal of opportunity—organizational career paths that have few opportunities for advancement and responsibility at middle and upper levels.

![]() The “fur-lined trap” and achievement addiction—organizational and career reward systems that so effectively reward specialized role performance that individuals have little energy remaining for broader development, family, and private life.

The “fur-lined trap” and achievement addiction—organizational and career reward systems that so effectively reward specialized role performance that individuals have little energy remaining for broader development, family, and private life.

![]() Career demands for integrative development—the extent to which a given career requires and/or allows development beyond specialization. For example, management at top levels requires an integrative perspective and organizations have policies such as job rotation to facilitate the development of this perspective.

Career demands for integrative development—the extent to which a given career requires and/or allows development beyond specialization. For example, management at top levels requires an integrative perspective and organizations have policies such as job rotation to facilitate the development of this perspective.

![]() Opportunities for creativity/role innovation (Schein, 1972)—the extent to which a career offers continuing challenges and opportunities for changing roles and job functions.

Opportunities for creativity/role innovation (Schein, 1972)—the extent to which a career offers continuing challenges and opportunities for changing roles and job functions.

The developmental model of experiential learning theory holds that specialization of learning style typifies early adulthood and that the role demands of career and family are likely to reinforce specialization. However, this pattern changes in midcareer. Specifically, as people mature, accentuation forces play a smaller role. To the contrary, the approach of the middle years brings with it a questioning of one’s purposes and aspirations, a reassessment of life structure and direction. For many, choices made earlier have led down pathways no longer rewarding, and some kind of change is needed. At this point, many finally face up to the fact that they will never realize their youthful dreams and that new, more realistic goals must be found if life is to have purpose. Others, even if successful in their earlier pursuits, discover that they have purchased success in career at the expense of other responsibilities (such as to spouse and children) or other kinds of human fulfillment. Continued accentuation of an overspecialized version of oneself eventually becomes stultifying—one begins to feel stuck, static, in a rut. The vitality of earlier challenges is too easily replaced by routinized application of well-established solutions. In the absence of new and fresh challenges, creativity gives way to merely coping and going through the motions. Many careers plateau at this time, and one faces the prospect of drying up and stretching out the remaining years in tedium. Finding new directions for generativity is essential.

Perhaps it is inevitable that specialization precede integration in development, inevitable that youth be spent in a search for identity in the service of society, until in a last reach for wholeness we grasp that unified consciousness that has eluded us. As William Butler Yeats so eloquently put it, “Nothing can be sole and whole that has not been rent.” For wholeness cannot be fully appreciated save in contrast to the experience of fragmentation, compartmentalization, and specialization. Kurt Lewin’s observation that pulsation from differentiation to integration is the throb of the great engine of development is writ large as a universal social pattern of socialization.

Adaptive Flexibility and Integrative Development

There is considerable agreement among adult-development scholars that growth occurs through processes of differentiation and hierarchic integration and that the highest stages of development are characterized by personal integration and integrity. From the perspective of experiential learning theory, this goal is attained through a dialectic process of adaptation to the world. Fulfillment, or individuation, as Jung calls it, is accomplished by expression of nondominant modes of dealing with the world and their higher-level integration with specialized functions. With integrative development comes an increasing freedom from the dictates of immediate circumstance and the potential for creative response. This structural potential is expressed behaviorally by the individual’s adaptive flexibility. As Werner put it:

In general, the more differentiated and hierarchically organized the structure of an organism is, the more flexible its behavior. This means that if an activity is highly hierarchized, the organism, within a considerable range, can vary the activity to comply with the demands of the varying situation. [Werner, 1948, p. 55]

Adaptive flexibility and the mobility it provides are the primary vehicles of integrative development. They are the means by which people transcend the fixity of their specialized orientation. Fixity can be inferred from the intrinsic trend of any evolution toward an end stage of maximum stability. Such maximum stability, as the end stage of a developmental sequence, implies the closing of growth—the permanence, for instance, of specialized reaction patterns. But fixity would finally lead to rigidity of behavior if not counter-balanced by adaptive flexibility. As most generally conceived, adaptive flexibility implies “becoming” as opposed to “being.”

Assessing Adaptive Flexibility: The Adaptive Style Inventory

One consequence of integrative development for those scientists who wish to predict and control human behavior is a certain amount of frustration, for with integrative development and its attendant adaptive flexibility comes increasing difficulty in the prediction of behavior. It is easy to predict behavior consequences in a low-level system (say, turning on a light switch) but far more difficult to predict behavior of higher-level systems capable of hierarchic integration (as with a computer). This problem is confounded when the attempt is made to characterize individuals as whole persons at a given stage of development. Developmental theorists have recognized this problem and attempted to deal with it in a number of ways—for example, by ad hoc concepts, as in Piaget’s concept of horizontal decalage (variability in cognitive structure from task to task in a given time period; compare Flavell, 1963, p. 23) or by simply averaging this variability and thus ignoring it.1

1. This averaging of stage variability is Loevinger’s approach: “One must immediately admit that most samples of behavior, e.g., test protocols, contain evidence of functioning on diverse levels. . . . Nonetheless, the first step in bringing the concept within scientific compass is measurement. A probabilistic modification of the hierarchies model both accommodates the complexities and assimilates them to the requirements of measurement” (1966, p. 202).

Another approach to these measurement problems is to use the level of adaptive flexibility itself as an indicator of the level of integrative development. Thus, if people show systematic variability in their response to different environmental demands, we can infer a higher level of integrative development. To accomplish this assessment, however, requires that two conditions be met. First, a holistic system of environmental demands that samples the person’s actual and potential life space is required. As Scott (1966) has pointed out, adaptive flexibility is meaningful only if there is some situation or circumstance being adapted to. Variability alone is not necessarily adaptive flexibility; it must be systemic variation in response to varying environmental demands. Second, the dimensions of personal-response flexibility and situation demand should be defined in commensurate terms. Flexibility of response should be measured along a dimension so that situation/person matches or mismatches can be identified that are related to the situation responded to. The theory of experiential learning provides a framework within which these conditions can be met. Toward this end, a modified version of the Learning Style Inventory called the Adaptive Style Inventory (ASI) was created. This instrument profiles the transactions between persons and their environment by providing them with a series of situations in the form of sentence stems (for example, “When I start to do something new”), which they complete by choosing between two responses, each response representing an adaptive mode (such as, “I rely on my feelings to guide me”—concrete experience; “I set priorities”—abstract conceptualization).

The ASI instrument is divided into four situations that the respondent must “adapt” to. These situations correspond to the four learning styles—divergent situations, assimilative situations, convergent situations, and accommodative situations. Each situation is characterized by two sentence stems, each with six pairs of response choices that present the four adaptive-mode responses in paired comparison fashion. The ASI thus yields an adaptive profile for the four different learning-style environments and an average adaptive profile across all four situations.

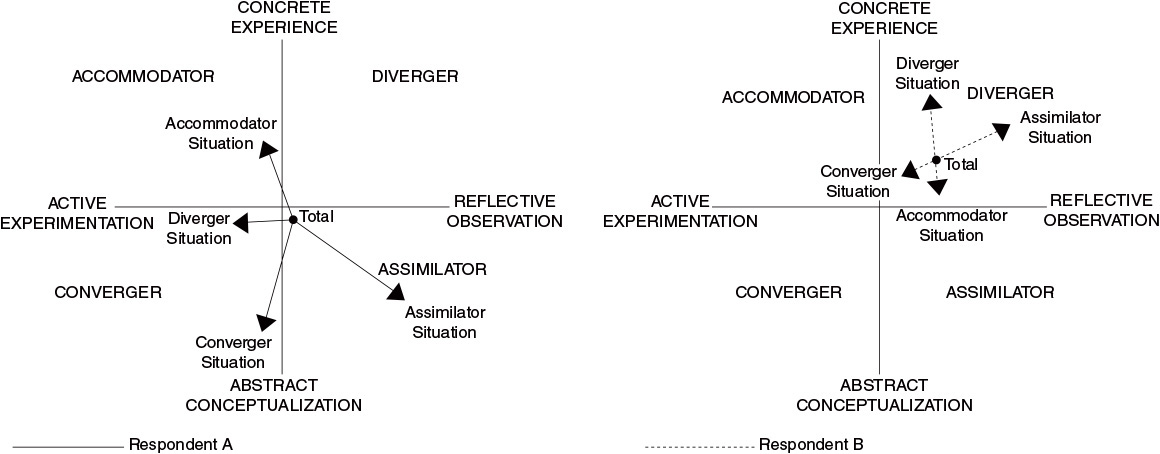

Responses to the ASI can be portrayed in a way that shows one’s adaptive orientations as points on a two-dimensional learning space. One point represents average responses across all situations. It is achieved by noting scores on the abstract-concrete dimension (AC-CE) and scores on the active-reflective dimension (AE-RO) and plotting a point at the juncture of these two points on the learning grid (see Figure 8.1). The same procedure is followed to portray how the person responded in each of the four kinds of situations. Arrows are then drawn from the total score to each of the situational scores. These arrows indicate the direction of the person’s response to each kind of situation. The amount of adaptive flexibility from situation to situation is indicated by the length of the arrows.

Figure 8.1 shows two sample responses to the ASI. Respondent A has a total score near the center of the grid, indicating a relative balance in the person’s average adaptive style. The responses to each environmental press are consonant with the press in three of the four instances. The modal response to the diverger situations is heavily active and does not differ significantly from the total score on the abstract-concrete dimension. It could be said that this person responded to three situational presses—accommodator, converger, assimilator—in terms consonant with those presses; that is, she responded to the situations by increasing emphasis on the adaptive modes “pulled for.” However, in diverger situations, the respondent responded primarily in an active mode, acting against the press of the situation.

Respondent B, on the other hand, has a total score well within the diverger quadrant, indicating a tendency to respond to all situations in a concrete and reflective mode. Each of the situational presses was responded to in terms other than conformity to the press of the environment (relative to the total score), except in converger situations. In diverger situations, this person responds to very concrete ways but also responds in slightly more active ways.

The response to diverger situations would be interpreted as more consonant with accommodator situations. (Admittedly, the response in terms of the total grid is still in the diverger quadrant, which makes the response still consonant with the situational press. However, the reference point for each person is not the theoretical center of the grid, but his or her own total score.) In accommodator situations, the person responds in a more abstract way and in a somewhat reflective way, contrary to the accommodator situational press, which demands a concrete and active response. In assimilator situations, respondent B responded in a reflective way, as would be demanded by the situation, but also responded in a concrete way, which is contrary to the assimilator situational press. Finally, this respondent responded to converger situations in ways appropriate to the converger situational press.

To assess the level of adaptive flexibility quantitatively, formulas were devised to determine how much the respondent varied his or her adaptive orientation from situation to situation. Five such variables were created: concrete experience adaptive flexibility (CEAF), reflective observation adaptive flexibility (ROAF), abstract conceptualization adaptive flexibility (ACAF), active experimentation adaptive flexibility (AEAF), and total adaptive flexibility (TAF).2 CEAF, for example, is the extent to which people vary their concrete experience orientation across the four situations. The total adaptive flexibility score (TAF) is the sum of CEAF, ROAF, ACAF, and AEAF. It should be noted that these scores do not take into account the direction of the person’s adaptation to a given situational demand but simply the degree of variation in adaptive modes from situation to situation, since adaptive flexibility is composed of both movement toward the press of a situation and movement in other directions.

The Relation between Adaptive Flexibility and Integrative Development

Armed with this ASI-based operational definition of adaptive flexibility, we can investigate the relation between adaptive flexibility and integrative development empirically. To do so, we studied three samples of midlife adults: a selected sample of 47 professional engineers and 23 professional social workers from the alumni study described in the last chapter, and a group of 39 midlife men and women of varying occupations who were participants in an intensive study of midlife adult development issues (see Kolb and Wolfe, 1981, for details). This latter group participated in an intensive series of self-assessment workshops over a three-year period, thus affording an in-depth assessment of their personalities and life situations.

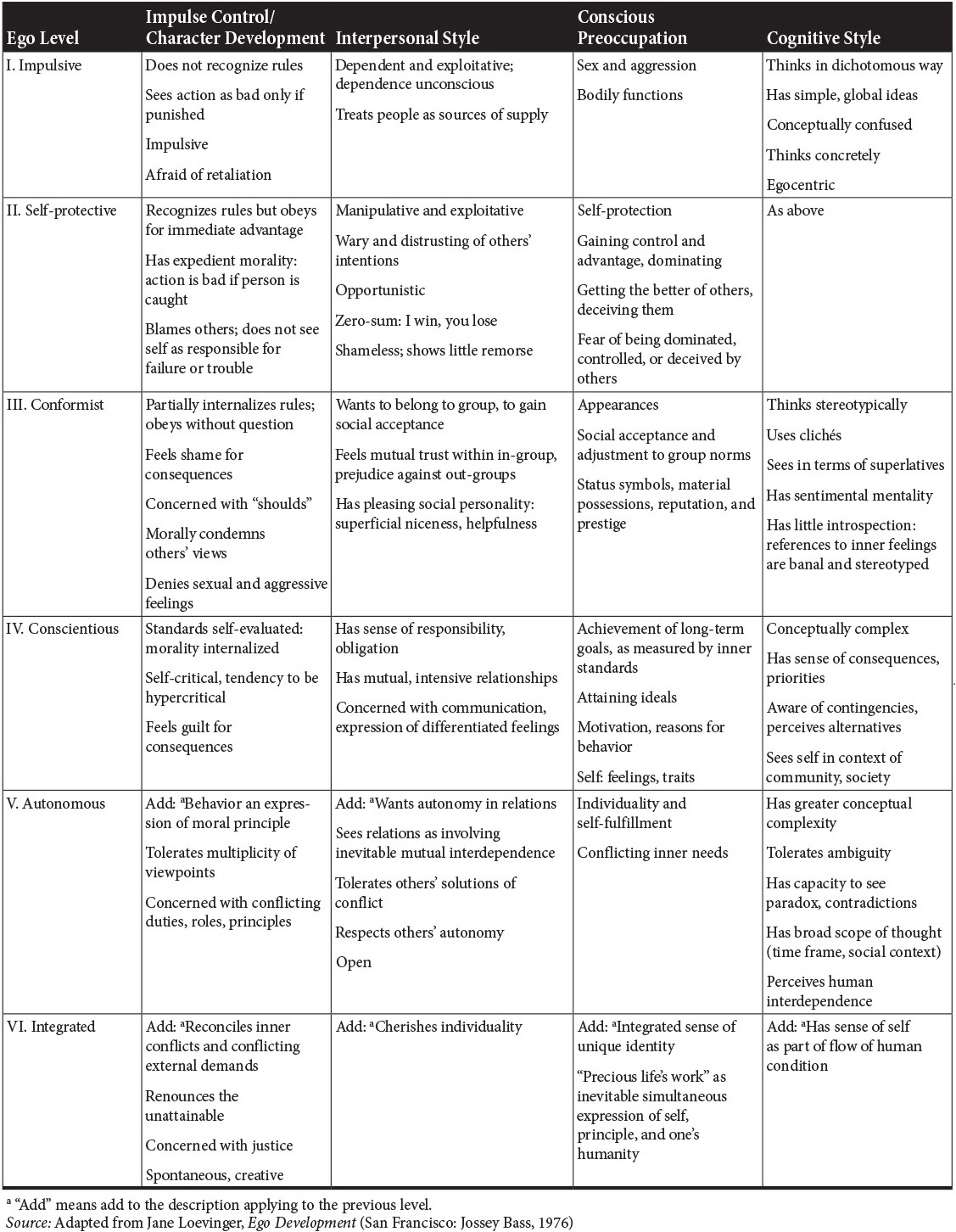

Ego Development One widely used measure of integrative development is Loevinger’s Sentence Completion Instrument (Loevinger, 1976). In developing her model of the stages of adult ego development, Loevinger drew heavily on the work of Piaget, Kohlberg, and Perry, as well as the psychoanalytic school of ego psychology, most notably Erik Erikson. Scores on the Sentence Completion Test give an indication of a person’s level of ego development as defined by her hierarchy of six ego-development stages—impulsive, self-protective, conformist, conscientious, autonomous, and integrated. As can be seen from Table 8.1, these stages are related to the six levels of adaptation defined in the experiential learning theory of development (see Table 6.1). In addition, Loevinger sees adaptive flexibility as a hallmark of development in her framework:

Flexibility in the exchanges with the environment is no less an important property for survival. Because organisms are dependent on environments and open to them, and because environments can change, organisms need to adjust and accommodate, to substitute a new response for a once successful one. . . . The degree of flexibility . . . may be an indication of the organism’s development. [Loevinger, 1976, p. 34]

For these reasons, we predicted a relationship between adaptive flexibility as measured by the ASI and a person’s level of ego development. As a test for this relationship, the three samples of midlife adults were given the ASI and the Sentence Completion Instrument, which was scored according to instructions in the Loevinger test manual (Loevinger and Wessler, 1970). Most respondents scored in the middle range of Loevinger’s scheme. There were no “impulsive” (level 1) or “self-protective” (level 2) people and no “integrated” (level 6) people in the sample. There was one “autonomous” person. Even with this restricted range of ego development, however, there was a significant positive relationship between total adaptive flexibility and ego-development level (r = .26, p < .003). Most of this covariation in adaptive flexibility occurred in reflective observation and abstract conceptualization (for instance, ego level with ROAF, r = .20, p < .02; with ACAF, r = .22, p < .01). To the extent that the ego-development measure is an indication of integrative development, we can conclude that the ASI measures of adaptive flexibility are also indicative of integrative development. A more detailed analysis of the data suggests, however, that the Loevinger instrument is perhaps more attuned to development of adaptive flexibility in the reflective and abstract adaptive modes than in the concrete and active orientation.

Self-direction Perhaps a more active indicator of integrative development is people’s ability to direct their own lives, to be an “origin” rather than a “pawn” (deCharms, 1968) in their life activities. The self-assessment workshops conducted for the group of midlife adults allowed researchers to rate participants on how self-directed they were in their current life situations (see Crary, 1981, for details). The criterion used for these ratings was the extent to which a person’s set of life contexts determined that person’s behavior as opposed to the behavior’s being controlled by the person.

The relationship between total adaptive flexibility and the person’s degree of self-directedness was significantly positive (r = .26, p < .05) and, as might be predicted, determined primarily by adaptive flexibility in active experimentation (self-directedness with AEAF, r = .28, p < .05). This suggests that those at higher levels of integrative development as measured by the ASI are more self-directed and display that self-directedness through choiceful variation of their active behavior in different situations.

Cognitive Complexity in Relationships The experiential learning theory of development describes affective development in concrete experience as a process of increasing complexity in one’s conception of personal relationships (see Table 6.1), resulting from integration of the four learning modes. Thus we would predict that increasing adaptive flexibility, particularly in the realm of concrete experience, would be associated with increased richness in construing one’s interpersonal world. A major component of internal structural complexity is the constructions, as expressed in the words one uses, which can be called upon to describe and manipulate one’s thoughts and interactions with the interpersonal environment. This notion was operationalized in the context of the self-assessment workshops. In the workshops, the midlife adults engaged in a number of exercises in which they portrayed the configuration of their life structures graphically and by analogy. During these exercises, the facilitating researchers noted the words each respondent used to describe his or her life structures. A list of each person’s words was later presented to the respondent for verification as the person’s own terminology. Each respondent had the opportunity to eliminate or add words in order to make the list truly representative of his or her set of constructs. The final list of constructs became the variable we are using here called “number of constructs.”

As predicted, total adaptive flexibility was positively correlated with the total number of constructs a person used to describe his or her interpersonal world (r = .25; p < .06). This relationship was most significantly evidenced in the area of concrete experience (CEAF with number of constructs, r = .28, p < .04).

Taken together, the results above suggest that overall adaptive flexibility and adaptive flexibility in the four adaptive modes are meaningful indicators of integrative development. Total adaptive flexibility as measured by the ASI is significantly related to the level of ego development, to self-direction, and to the complexity of one’s interpersonal constructs. Ego development, at least as it is measured in the Loevinger model, is most strongly associated with adaptive flexibility in reflection and conceptualization, reflecting the development and manipulation of internalized hierarchical structures for construing the world that characterizes higher levels of cognitive and ego development. Increased self-direction is more associated with flexibility in behavioral actions, and richness in one’s constructs about the interpersonal world is associated most strongly with flexibility in concrete experiencing. These results, although limited to one sample, are promising, for they offer a measure of integrative development via the ASI that is sensitive both to development as a unitary process and to specialized development in different adaptive modes.

The Integrated Life Style

What can be said of the nature of the integrated life? How do people cope with the integrative challenges of adult life, and what can we learn from their example? Further results from our ASI study of adaptive flexibility, along with the case-by-case examination of the individual lives in our study of midlife adults, suggest some important characteristics of the integrated lifestyle.

Proactive Adaptation First, integrated people both adapt to and create their life structures. Their relationship with the world and others around them is transactional, in that they are proactive in the creation of their life tasks and situations and are shaped and molded by these situations as well. Paulo Freire describes this integrative stance toward one’s life context as follows:

Integration with one’s context, as distinguished from adaptation, is a distinctively human activity. Integration results from the capacity to adapt oneself to reality plus the critical capacity to make choices and to transform that reality. To the extent that man loses his ability to make choices and is subjected to the choices of others, to the extent that his decisions are no longer his own because they result from external prescriptions, he is no longer integrated. Rather, he has adapted. He has “adjusted.” Unpliant men, with a revolutionary spirit, are often termed “maladjusted.”

The integrated person is person as subject. In contrast, the adaptive person is person as object, adaptation representing at most a weak form of self-defense. If man is incapable of changing reality, he adjusts himself instead. Adaptation is behavior characteristic of the animal sphere; exhibited by man, it is symptomatic of his dehumanization. Throughout history men have attempted to overcome the factors which make them accommodate or adjust, in a struggle—constantly threatened by oppression—to attain their full humanity.

As men related to the world by responding to the challenges of the environment, they began to dynamize, to master, and to humanize reality. They add to it something of their own making, by giving temporal meaning to geographic space, by creating culture. This interplay of men’s relations with the world and with their fellows does not (except in cases of repressive power) permit societal or cultural immobility. As men create, re-create, and decide, historical epochs begin to take shape. And it is by creating, re-creating, and deciding that men should participate in these epochs. [Freire, 1973, pp. 3–4]

We found tantalizing suggestions of this proactive stance among integrated people when we examined the ASI adaptive flexibility scores of low- and high-ego-development people in our samples of adult professionals and midlife persons. Low-ego-development people, as we have already seen, showed less flexibility and variation from situation to situation. In addition, a case-by-case examination suggests that most of this variation was toward the press of the situation, such as becoming more active and concrete in accommodative situations or more abstract and reflective in assimilative situations. This pattern is suggestive of adjustment, or what Freire calls adaptation. High-ego-development people, on the other hand, showed greater variation, and much of this variation was counter to the press of the situation, such as responding reflectively in active situations or concretely in abstract situations. Here it appears that integrated people respond more creatively to situations supplying perspectives that from a holistic-learning point of view are missing. Thus, high-ego-development persons may respond to the abstract task of understanding the basic principles of something by seeking and exploring concrete examples, or they may deal with an active task such as completing a task on time by reflectively creating a plan.

This integrated response produces a creative tension between the person and his or her life situations, a tension that may in fact be essential for the creative response that integrative development engenders. Howard Gruber describes the importance of being one’s own person in the creative process:

This obligation to move back and forth between radically different perspectives produces a deep tension in every creative life. In the course of ordinary development similar tensions begin to appear. What we mean by such terms as adaptation and adjustment is the resolution of these tensions. But that is not the path of the creative person. He or she must safeguard the distance and the specialness, live with the tension. [Feldman, 1980, p. 180]

Rich Life Structures A second characteristic of the integrated life style is seen in the life structures of integrated people. The life structures of integrated persons mirror the integrative complexity of their personalities. It was Kurt Lewin (1951) who first noted the isomorphism between the person’s development level and the level of complexity of his or her life space. When we examine the life structures of those who score high on the ASI measures of adaptive flexibility, we see complex, flexible, and highly differentiated life structures. These people experience their lives in ways that bring variety and richness to them and the environment. They engage with their environments by flexibly moving within those environments, by creating highly differentiated life spaces and relationships, and by building networks of relationships and contexts. Marcy Crary has defined these dimensions thus:

Some people lead lives with a great deal of freedom of movement and variation in involvement within their different contexts. Either through their own person and/or the nature of the contexts they engage within, there is an appearance of a great deal of flexibility in their life structures. The contrasting lifestyle is one in which there is much routine, pre-arranged structuring of day-to-day events, likely leading to much repetition of events, activities, relationships within each of the person’s contexts. Low rating on this scale would likely imply a higher degree of role-bounded situations and involvements. A high rating implies a relatively greater amount of “spontaneous” living. [Crary, 1979, p. 20]

A related dimension is that of differentiation within a person’s life space. Crary states:

This dimension relates to the degree of heterogeneity of contexts within a person’s life-space. A life-space which is differentiated is multifaceted, containing a variety of components or regions within its boundaries. . . . Applied to the life-space as a whole (within and across contexts) the low end of the scale denotes a life space in which not one of the contexts seem to stand apart from the others in terms of the person’s experience of them. The high rating refers to a life style in which the person clearly experiences variation and contrasts within and across their different contexts. [Crary, 1979, p. 10]

When Crary’s ratings on these dimensions of life structure were correlated with adaptive-flexibility scores, significant relationships emerged. Flexible life structures were significantly associated with the integrated adaptively flexible people (TAF with flexibility in life structure, r = .36, p < .01; for AEAF, r = .41, p < .005; for ACAF, r = .37, p < .01; N.S. for ROAF and CEAF). Differentiation in life structure was also associated with adaptive flexibility (TAF with differentiation in life structure, r = .35, p < .01; for AEAF, r = .34, p < .02; for ACAF, r = .40, p < .005; for ROAF, r = .30, p < .03; N.S. for CEAF). The integrated person seems capable of constructing a rich, complex, and flexible life space that sustains him or her and provides new opportunities for growth.

Conflict A key to the ability to manage complexity lies in a final characteristic of the integrated lifestyle identified in our research—harmony, the constructive management of conflict. We found in our sample of midlife adults no significant difference overall between high-adaptive-flexibility and low-adaptive-flexibility people in the amount of stress and change they had to cope with in their lives. Yet when we measured the amount of conflict these people experienced in their lives, the adaptively flexible, integrated persons experienced much less conflict than those with low adaptive flexibility. A panel of researchers evaluated each respondent on a number of dimensions, including the degree of conflict. Conflict was defined as the extent of “incompatibilities, force and counter-force” (Crary, 1979) a person experiences among the various settings in his or her life, without regard to the number or complexity of the relationships among these settings. This rating was based on various exercises that respondents completed in the self-assessment workshops. These exercises served to portray the respondents’ life space, their relationships with others, and a longitudinal view of their past and possible future.

When this rating was correlated with ASI adaptive-flexibility scores, high adaptive flexibility was associated with low conflict. (TAF with degree of conflict, r = −.34, p < .02; for AEAF, r = −.30, p < .03; for ACAF, r = −.24, p < .06; for CEAF, r = −.27, p < .05; N.S. for ROAF.) Further analysis, controlling for the amount of conflict in each individual life structure, showed that adaptively flexible people experienced the least stress in their lives in spite of the fact that their life structures, as we have seen, are the most complex. This harmony in life structure occurred in the context of the more balanced life structure that characterized most of those in our midlife sample (Kolb and Wolfe, 1981). Early in their lives, people have life structures that are heavily oriented around work (mainly for men) or family (for women). At midlife comes more balance in life investment, a balance that may be the foundation for the harmony and lower conflict in the lives of integrated people.

On Integrity and Integrative Knowledge

The pinnacle of development is integrity. It is that highest level of human functioning that we strive consciously and even unconsciously, perhaps automatically, to reach. The motivation to achieve integrity is a profound gift of humanity—a desire to reach out, understand, become, and grow, a pervasive motivation for mastery that Robert White has called motivation for competence. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language (Stein, 1966) offers three definitions of integrity: “1. soundness of and adherence to moral principle and character . . . ; 2. the state of being whole, entire, or undiminished . . . ; 3. sound, unimpaired, or perfect condition” (p. 738). All these usages of the term are essential to define the concept as it is used here, but Warren Bennis’s definition of integrity is perhaps more instructive of its meaning for the theory of experiential learning:

Integrity. Integration. The integral personality. Such permutations are permissible plays on the word, which shares roots with integer, the untouchable (in and tanger) whole number which links the most abstract of endeavors, mathematics, to the human condition. I am talking about the kind of unity—of purpose, goals, ideas, and communication—that makes three musketeers, Three Musketeers. It’s a merging of identities and resolves into a coherent and effective whole. [Bennis, 1981–82, p. 4]

In the theory of experiential learning, integrity is a sophisticated, integrated process of learning, of knowing. It is not primarily a set of character traits such as honesty, consistency, or morality. These traits are only probable behavioral derivations of the integrated judgments that flow from integrated learning. Honesty, consistency, and morality are usually, but not always, the result of integrated learning. One need only reflect on the “immoral” behavior of men like Copernicus and Galileo to realize that integrity is the learning process by which intellectual, moral, and ethical standards are created, not some evaluation based on current moral standards and worldviews.

It is misleading to confuse these products of integrity, absolute and reasonable as they appear, with the process that creates them, for creators precede their creations in time and must create with no fixed absolutes to guide them. Integrity as a way of knowing embraces the future and the unknown as well as the codified conventions of social knowledge that are, by their nature, historical record. The prime function of integrity and integrative knowledge is to stand at the interface between social knowledge and the ever-novel predicaments and dilemmas we find ourselves in; its goal is to guide us through these straits in such a way that we not only survive, but perhaps can make some new contribution to the data bank of social knowledge for generations to come.

The knowledge structure of integrity does not comform to any one of the four knowledge structures identified in Chapter 5; it is usually some integrative synthesis of these in the emergent historical moment. As such, integrative knowing is essentially eclectic, if by the term is meant, “not consistent with current forms.” It stands with one foot on the shore of the conventions of social knowledge and one foot in the canoe of an emergent future—a most uncomfortable and taxing position, one that positively demands commitment to either forging ahead or jumping back to safety. Stephen Pepper proposes the following guidelines for a reasonable eclecticism:

In practice, therefore, we shall want to be not rational but reasonable, and to seek, on the matter in question, the judgment supplied from each of these relatively adequate world theories. If there is some difference of judgment, we shall wish to make our decision with all these modes of evidence in mind, just as we should make any other decision where the evidence is conflicting. In this way we should be judging in the most reasonable way possible—not dogmatically following only one line of evidence, not perversely ignoring evidence, but sensibly acting on all the evidence available. [Pepper, 1942, pp. 330–331]

Thus, in integrative learning, knowledge is refined by viewing predicaments through the dialectically opposed lenses of the four basic knowledge structures and then “acting sensibly.”

The way in which this process is carried out is in many ways the topic of Pepper’s last book, Concept and Quality. Here, Pepper proposes a fifth world hypothesis for integrative learning—selectivism—with the root metaphor purposive act. For it is in a single act of purpose that the psychological world of feeling, thought, and desire (“I want that goal”) and the physical world (myself and the world as physical/chemical substances) are integrated, that value and fact, quality and concept, are fused. It is here that goal meets reality, “ought” meets “is.” Selectivism as a world hypothesis turns out to be very much like contextualism or modern-day pragmatism in its emphasis on novelty and uncertainty as the basic adaptive problem facing the human species. The basic paradigm of selectivism is one where, seeking goals as judgments of value, we pursue realities based on judgments of fact. Reality in this paradigm is “what pushes back,” to use E. A. Singer’s (1959) apt phrase. Reality allows our conceptions of it, it does not cause them. Von Glasersfeld describes the selectivist paradigm thus:

Roughly speaking, concepts, theories, and cognitive structures in general are viable and survive as long as they serve the purposes to which we put them. . . .

If we accept this concept of viability, it becomes clear that it would be absurd to maintain that our knowledge is in any sense a replica or picture of reality. . . . [W]hile we can know when a theory or model knocks against the constraints of our experiential world, the fact that it does not knock against them but “gets by” and is still viable, does in no way justify the belief that the theory or model therefore depicts a “real” world. . . .

[W]e must never say that our knowledge is “pure” in the sense that it reflects an ontologically real world. Knowledge neither should nor could have such a function. The fact that some construct has for some time survived experience—or experiments for that matter—means that up to that point it was viable in that it bypassed the constraints that are inherent in the range of experience within which we were operating. But viability does not imply uniqueness, because there may be innumerable other constructs that would have been as viable as the one we created. [von Glasersfeld, 1977, pp. 7–14]

An important implication of this constructionist view of reality is that theories are always combinations of value and fact, since it is value judgments that determine which aspects of reality are selected to be explored and how that exploration will take place. As a result, a primary dialectic that must be resolved in integrative knowledge is that of value and fact. Integrity requires the thoughtful articulation of value judgments as well as the scientific judgment of fact. The essential character of this dialectic integration is one of valuing via apprehension and creating facts via comprehension. The sense in which civilization is a race between such integrated learning and chaos is captured beautifully in Hegel’s image of the owl of Minerva, the symbol of wisdom, beginning its flight just as darkness threatens.

To say one more word about preaching what the world ought to be like, philosophy always arrives too late for that. As thought of the world it appears at a time when actuality has completed its developmental process and is finished. What the conception teaches history also shows as necessary, namely, that only in a maturing actuality the ideal appears and confronts the real. It is then that the ideal rebuilds for itself this same world in the shape of an intellectual realm, comprehending this world in its substance. When philosophy paints its gray in gray, a form of life has become old, and this gray in gray cannot rejuvenate it, only understand it. The owl of Minerva begins its flight when dusk is falling. [Hegel, 1820]

Integrity requires that we learn to speak unselfconsciously about values in matters of fact. We need to develop, in the arena of values, inquiry methods that are as sophisticated and powerful as the methods of science have been in matters of fact.

No less significant for the attainment of integrative knowledge is the resolution of the dialectic between relevance and meaning. Western industrial societies have nearly run amok in their embrace of the extroverted materialism of relevance, ignoring and even actively denying the meaning of religious, humanistic, and spiritual ideals. Cast adrift from any meaningful connection with relevant work in the material world, internal lives can become wastelands of existential angst or sensual hedonism. The challenge of integrative knowledge, here, is to reimbue the pragmatic short-term choices and judgments that have given us polluted air and water, the threat of instant nuclear annihilation, the creation of a permanent underclass, and other such harmful side effects of our particular form of technological civilization, with the long-range perspective of meaning that arises from reflection on the human condition and the history of civilization. What we need is a theory of intentional action to guide us through these choices, to lay bare the plan whereby humanity has made these judgments in the past, and to suggest new “rules” for current circumstances.

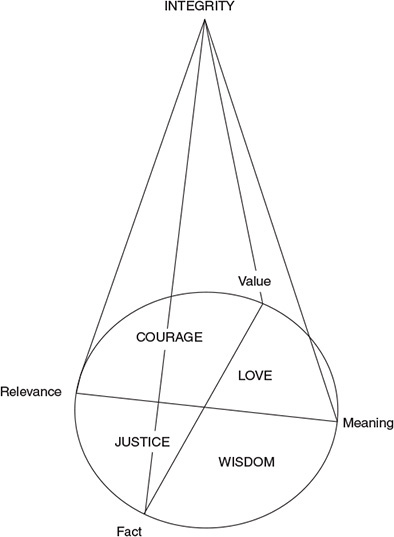

In resolving the dialectic conflicts between value and fact, meaning and relevance, integrity is the master virtue. In a way that is similar to the identification of learning styles we can see in typical resolutions of these two dialectics, more specialized virtues (see Figure 8.2) whose primary function is to preserve and protect one pole of each dialectic: wisdom, the protector of fact and meaning; justice, the protector of fact and relevance; courage, the protector of relevance and value; and love, the protector of value and meaning. These specialized virtues are counterpress behavioral injunctions: they instruct us to act against the demand characteristic of life situations, to create, not adjust. Wisdom dictates that we do not blindly follow the implications of knowledge but that we be choicefully responsible in the use of knowledge. Courage tells us to push forward when circumstance signals danger and retreat. Love requires that we hold our selfish acts in check until we have viewed the situation from the perspective of the other—the Golden Rule. And justice demands fair and equitable treatment for all against the expedience of the special situation.

Figure 8.2 Integrity as the Master Virtue Integrating Value and Fact, Meaning and Relevance, and the Specialized Virtues of Courage, Love, Wisdom, and Justice

The late Niels Bohr once remarked that his interest in complementarity in physics had been stimulated by the thought that one cannot know another human being at the same time in the light of love and in the light of justice. Thus, the specialized virtues have a bias in favor of the dialectic poles they protect. It remains for integrity and integrated knowing to rise above these biases for the truly integrated judgment.

The Experience of Integrity—The Mandala Symbol

The experience of integrity and the characteristics of integrated knowing can be illustrated by the structure of the symbol that has represented them throughout the history of humanity. The mandala symbol is the most important symbol in the Jungian panoply of the symbols and archetypes that populate the human psyche. This symbol of wholeness, unity, and integrity is to be found in most of the world’s religions—the Christian cross, the star of David, and the intertwined fishes of yin and yang. Its value as a tool for meditation is renowned, producing a timeless centering of consciousness in which “you unify the world, you are the world itself, and you are unified by the world.” Jung (1931) collected examples of the mandala symbol from paleolithic to modern times, from Eastern religions to Western art and literature. He saw in these symbols the characteristics of individuation, of integrity.

Mandala means a circle, especially a magic circle, signifying the integrity of experience, an eternal process where endings become beginnings again and again. “The mandala form is that of a flower, cross or wheel with a distinct tendency towards quadripartite structures” (Jung, 1931, p. 100). The typical four-part structure of the mandala often represents dual polarities, as in the Tibetian Buddhist Tantric mandala shown here (Figure 8.3). Here, double dorjes (dorje = “thunderbolt” of knowledge that cuts through confusion with penetrating wisdom) form a cross representing the interconnection of the earth realm (matter) and the realm of heaven (spirit).

It is the integration of these polarities that fuels the endless circular process of knowing. “Psychologically this circulation would be the ‘turning in a circle around oneself’; whereby, obviously, all sides of the personality become involved. They cause the poles of light and darkness to rotate. . . .” (1931, p. 104).

The product of this dialectic circulation process is a centering of one’s experience. “The mandala symbol is not only a means of expression but works an effect. It reacts upon its maker. . . . [By meditating on it] the attention or, better said, the interest, is brought back to an inner sacred domain, which is the source and goal of the soul. . . .” [1931, pp. 102–103]. Warren Bennis, in his recent study of effective leaders in all walks of life, has noted that this “centeredness” is a common trait among many of them (1980, p. 20). With centering comes the experience of transcendence, the conscious experience of hierarchic integration where what was before our whole world is transformed into but one of a multidimensional array of worlds to experience. In interviewing the associates of people who are perceived to “have integrity,” I have been struck by the awe in which their integrative judgments are held; judgments that, like Solomon’s decision to cut the baby in half, appear to rise above the confines of justice to include love; judgments that are seen as not only wise but courageous. The capacity for such integrated judgment seems to be borne out of transcendence, wherein the conflicts that those of us at lower levels of insight perceive as win-lose are recast into a higher form that can make everyone a winner, or can make winning and losing irrelevant. And finally, with centering comes commitment in the integration of abstract ideals in the concrete here-and-now of one’s life. When we act from our center, the place of truth within us, action is based on the fusion of value and fact, meaning and relevance, and hence is totally committed. Only by personal commitment to the here-and-now of one’s life situation, fully accepting one’s past and taking choiceful responsibility for one’s future, is the dialectic conflict necessary for learning experienced. The dawn of integrity comes with the acceptance of responsibility for the course of one’s own life. For in taking responsibility for the world, we are given back the power to change it.

Update and Reflections

Lifelong Learning and the Learning Way

“For he had learned some of the things that everyman must find out for himself, and he had found out about them as one has to find out, through errors and through trial, through fantasy and delusion, through falsehood and his own damn foolishness, through being mistaken and wrong and an idiot and egotistical and aspiring and hopeful and believing and confused. As he lay there he had gone back over his life, and bit by bit, had extracted from it some of the hard lessons of experience. Each thing he learned was so simple and so obvious once he grasped it, that he wondered why he had not always known it. . . . Altogether, they wove into a kind of leading thread, trailing backward through his past and out into the future. And he thought now, perhaps he could begin to shape his life to mastery, for he felt a sense of new direction deep within him, but whither it would take him he could not say.”

—Thomas Wolfe, You Can’t Go Home Again

When I was doing the research for Experiential Learning, I was aided immensely by our Organization Behavior Department’s project on Lifelong Learning and Development funded by two large grants from the Spencer Foundation (Wolfe and Kolb, 1980) and the National Institute for Education (Kolb and Wolfe, 1981) aimed at increasing understanding of two topics that sparked a lot of national attention at the time: lifelong learning and adult development. Since then “lifelong learning” has steadily moved from an inspiring aspiration to a necessary reality. The transformative global, social, economic, and technological conditions that were envisioned over forty years ago have come to fruition in a way that requires a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between learning and education. From a front-loaded, system-driven educational structure dominated by classroom learning, we are in the process of transitioning to a new reality where individual learners are becoming more responsible for the direction of their own learning in a multitude of learning environments that span their lifetime. This transition parallels other self-direction requirements that have been placed on individuals by the emergence of the global economy such as responsibility for one’s own retirement planning and health care. Aspin and Chapman (2000) in their review of these developments identify what they call the triadic nature of lifelong learning encompassing three areas with different learning needs—learning for economic progress and development, learning for personal development and fulfilment, and learning for the development of a just and thriving democracy. The challenge of lifelong learning is not just about learning new marketable skills in an ever-changing economy. It is about the whole person and their personal development in their many roles as family member, citizen, and worker.

The solution is not a world of self-taught autodidacts. Social institutions, government policy makers, and educators face fundamental changes to support lifelong learners. While the individual is primarily responsible for his or her learning, it must happen in an interdependent relationship with others. Hinchcliffe, in his critical rethinking of lifelong learning, describes the situation thusly, “For in embracing the concept of lifelong learning one also embraces a whole pedagogy: one cannot have a lifelong learner without bringing in the associated features of the reflective learner, teaching through facilitation, the emphasis on the transferability of learning and the importance of self-direction and self-management. One cannot be a lifelong learner unless one absorbs a whole discourse of pedagogy. . . a person has to live a whole ideology so that one must ‘acquire the self-image of a lifelong learner’” (2006, p. 97). In his rethinking, he emphasizes the organic learner who is an interdependent actor, a becoming self immersed in the contextual world of practices. He emphasizes “the activity-based nature of learning which is experiential, collaborative, and often activated by individual learners rather than trainers or teachers” (2006, p. 99). Su adds the importance of a “being” versus “having” approach to lifelong learning: “The ability that a lifelong learner is expected to demonstrate changes from a focus on how much ‘static’ knowledge one has to the development of a dynamic ability to make sense of knowledge in order to be within change. This dynamic ability, which insists on human agency, and thereby on the possibility of flexibility, serves as the foundation for the transformation and development of adult learners into lifelong learners” (Su, 2011, p. 58). Peter Vaill in Learning as a Way of Being (1996) makes a similar point stressing the importance of approaching the turbulent change of an emerging world of “permanent white water” with a beginner’s mind.

The Learning Way

Experiential learning theory provides a framework for such a program for the lifelong learner; helping learners understand and adapt to these new circumstances through deliberate experiential learning (Passarelli and Kolb, 2011). Learning can have magical transformative powers. It opens new doors and pathways, expanding our world and capabilities. It literally can change who we are by creating new professional and personal identities. Learning is intrinsically rewarding and empowering, bringing new avenues of experience and new realms of mastery. In a very real sense, you are what you learn.

The learning way is about approaching life experiences with a learning attitude. It involves a deep trust in one’s own experience and a healthy skepticism about received knowledge. It requires the perspective of quiet reflection and a passionate commitment to action in the face of uncertainty. The learning way is not the easiest way to approach life, but in the long run, it is the wisest. Other ways of living tempt us with immediate gratification at our peril. The way of dogma, the way of denial, the way of addiction, the way of submission, and the way of habit; all offer relief from uncertainty and pain at the cost of entrapment on a path that winds out of our control. The learning way requires deliberate effort to create new knowledge in the face of uncertainty and failure, but opens the way to new, broader, and deeper horizons of experience.

The Learning Way Is a Way of Experiencing It is a way of being present with the world in the way it is, a way of becoming through being. Opening oneself to experience is necessary for learning and renewal. James March described experience as ambiguous, while William James saw pure experience as having infinite depth, mysterious and even spiritual. The first three quarters of the learning cycle from experiencing to acting all happens in our heads. The last quarter, from after we act to the ensuing experiences, happens in what we naively call “the real world.” Here there is novelty, uncertainty, pain and joy, unexpected consequences, and wonderful surprises. D. H. Lawrence describes it as “Terra Incognita”:

There are vast realms of consciousness still undreamed of

vast ranges of experience, like the humming of unseen harps,

we know nothing of, within us.

Oh when man escaped from the barbed wire entanglement

of his own ideas and his own mechanical devices

there is a marvellous rich world of contact and sheer fluid beauty

and fearless face-to-face awareness of now-naked life

and me, and you, and other men and women

and grapes, and ghouls, and ghosts and green moonlight

and ruddy-orange limbs stirring the limbo

of the unknown air, and eyes so soft

softer than the space between the stars.

And all things, and nothing, and being and not-being

alternately palpitant,

when at last we escape the barbed-wire enclosure

of Know Thyself, knowing we can never know,

we can but touch, and wonder, and ponder, and make our effort

and dangle in a last fastidious fine delight

as the fuchsia does, dangling her reckless drop

of purpose after so much putting forth

and slow mounting marvel of a little tree. (Lawrence, 1920, p. 1)

Ideally we would live each successive life experience fully—present and aware in the moment, taking it in fully. Yet, many of us live our daily lives making little or no conscious effort to learn from our experiences. While research in many areas has shown that experience alone does not produce much learning, many tend to assume that effective learning happens automatically and give little thought to how they learn or how they might improve their learning capability. Research on automaticity described earlier suggests that many of the activities of our daily lives are conducted on “automatic pilot” without conscious awareness and intention (Bargh and Chartrand, 1999). When I first read about the Theraveda Buddhism concept of moment experiencing as a string of pearls and Kahneman’s (Kahneman and Riis, 2005) estimate that we have 20,000 such moments every day, accumulating a half billion moments in 70 years, my spontaneous reaction was, “Wow, I have sure missed a lot in my life!” (Chapter 4 Update and Reflections, pp. 138–139)

The Learning Way Is the Way of Self-Creation Looking back, your life can be seen as a succession of these experiences, some of which you created for yourself and some that were thrust upon you. These life events are strung together like beads on a string defining that remarkable continuity that determines who you are. Looking forward to the future, the beads are only dreams and distant visions of future experiences. Your experience in this present moment is all that actually exists. In it you are fashioning a bead of meaning for the past and choosing the next experience ahead. The next experience offers new potentialities for meaning and choice, and so on in a lifelong process of self-creation and learning. As Oprah Winfrey has said, “With every experience, you alone are painting your own canvas, thought by thought, choice by choice.”

The learning way is about awakening the learning life force that lies within all of us. It is a power that we share with all living things, autopoeisis, the power of self-making. To open oneself and receive this life energy conveys magical powers of self-transformation. Learning from conscious experience is the highest form of the learning life force. Every human invention and achievement is the result of this process. In some spiritual traditions we humans are thought to be basically “asleep”; going through this process in a semi-conscious way, strangely disengaged from our own lives. The learning way is about awakening to attend consciously to our experience and deliberately choose how it influences our beliefs and how we will live our lives. The spiral of learning from experience is the process through which we consciously choose, direct, and control life experiences. By placing conscious experience at the center of the learning process we can literally create ourselves through learning.

The Learning Way Is a Way of Humility In the face of the infinite depth and breadth of experience one cannot help but be humbled by our limited partaking of it, drinking from the ocean of experience teacup by teacup, recognizing that our previous conceptions must always be tested by new emerging realities and a desire to learn. Humility is characterized by open-mindedness, a willingness to make mistakes and seek advice (Tangney, 2000). The humble way eschews self-preoccupation and is a process of becoming “unselved” (Templeton, 1997); recognizing our place as one of our 6 billion fellow humans on this small planet in the wider universe.

The Learning Way Is a Moral Way This last chapter of Experiential Learning describes integration and integrity as the culmination of the lifelong process of learning from experience, uniting the virtues of love, justice, courage, and wisdom. Critics have described experiential learning as a self-centered liberal humanism unconcerned about others: “Underneath the avowal that community is indispensable is a longing for a unitary, authentic self, untouched by the demands of human mutuality. . . . Experiential learning encourages psychic growth by freeing us from the oppression of other people’s choices” (Michelson, 1999, p. 140). Yet empathy, the deep experiencing of others, must be the motivational source of the emotional compassion that drives the imperative to act morally with others. I have already described (Chapter 6 Update and Reflections) Rogers’ theory that morality emerges from the deep experiencing of the human being. It is an inside-out process rather than the outside-in prescription from the imposition of an external moral system or dogma. The experiential learning theory way suggests that abstract moral principles must be integrated into the experience and context of the person in order to guide moral action.

Deliberate Experiential Learning

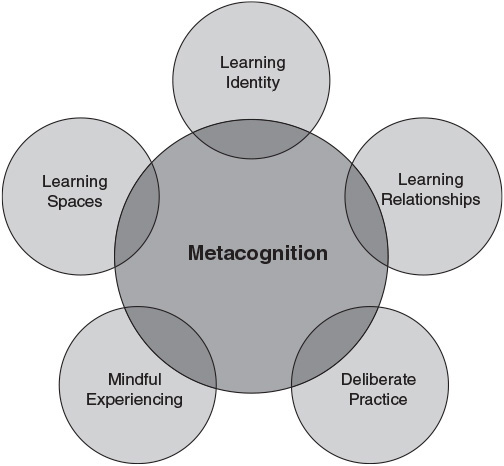

This process of experiencing with awareness to create meaning and make choices is what we call deliberate experiential learning. Deliberate learning requires mastery of experiential learning, or more particularly, it requires a personal understanding of one’s unique way of learning from experience and the ability to intentionally direct and control one’s learning. In short, one needs to be in charge of their learning to be in charge of their life. We have identified five metacognitive practices that can awaken and enhance the power of learning that lies within (Kolb and Kolb, 2009; Passarelli and Kolb, 2011; Kolb and Yeganeh, 2015). The five areas of metacognitive regulation are: learning identity, learning spaces, learning relationships, mindful experiencing, and deliberate practice (see Figure 8.4).

Metacognition—The Key to Deliberate Learning

Deliberate experiential learning requires individual conscious metacognitive control of the learning process that enables monitoring and selecting learning approaches that work best in different learning situations. James Zull described metacognition as the culmination of the journey from brain to mind—the mind’s ability to reflect on itself and control its own process. “In many ways, a learner’s awareness and insight about development of her own mind is the ultimate and most powerful objective of education; not just thinking, but thinking about thinking. It is when our mind begins to comprehend itself that we can say we are making progress. This ability may be the highest and most complex mental capability of the human brain. It is the thread that weaves back and forth through the cloth of the mind. . . . Gaining a metacognitive state of mind offers greater possibilities for experiencing the joy of learning than, perhaps, any of the other objectives or goals discussed so far” (2011, Chapter 10).

The concept of metacognition originated in the work of William James in his examination of the role of attention in experience and his ideomotor theory of action described in his two-volume magnum opus, The Principles of Psychology (1890). For James, attention plays its focus “like a spotlight” across the field of consciousness in a way that is sometimes involuntary, as when a bright light or loud noise “captures” our attention, but often voluntary. Voluntary attention is determined by one’s interest in the object of attention. He defines a spiral of interest-attention-selection that creates a continuous ongoing flow of experience summarized in the pithy statement—“My experience is what I agree to attend to” (1890, p. 403). He defines interest as an “intelligible perspective” that directs attention and ultimately selection of some experiences over others. Selection feeds back to refine and integrate a person’s intelligible perspective, serving as “the very keel on which our mental ship is built” (James cited in Leary 1992, p. 157). In his chapter on will, James developed a theory of intentional action which is essential for any metacognitive knowledge to be useful in improving one’s learning ability. His ideomotor action theory states that an idea firmly focused in consciousness will automatically issue forth into behavior—“Every representation of a movement awakens in some degree the actual movement which is the object; and awakens it in a maximum degree whenever it is not kept from so doing by an antagonistic representation present simultaneously to the mind” (James, 1890, p. 526).

Flavell (1979) re-introduced the concept of metacognition in contemporary psychology, dividing metacognitive knowledge into three sub-categories: (1) knowledge of person variables referring to general knowledge about how human beings learn and process information, as well as individual knowledge of one’s own learning processes; (2) task variables including knowledge about the nature of the task and what it will require of the individual; (3) knowledge about strategy variables including knowledge about ways to improve learning as well as conditional knowledge about when and where it is appropriate to use such strategies. Until recently, research on metacognitive learning has explored the influence of only relatively simple models of learning. For example, a study of fifth grader self-paced learning of stories found that the best students spent more time studying difficult versus easy stories, while there was no difference in study times for the poorer students. The findings suggest that the poorer students lacked a metacognitive model that dictated a strategy of spending more time on difficult learning tasks (Owings, Peterson, Bransford, Morris, and Stein, 1980).

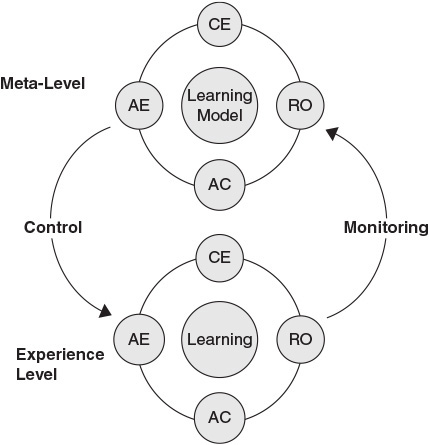

More recently Nelson (1996) and his colleagues have developed a model that emphasizes processes of monitoring and control in metacognition. An individual monitors their learning process at the experience level and relates the observations to a model of their learning process at the meta-level. The results of the conscious introspection are used to control actual learning at the experience level. We (Kolb and Kolb, 2009) have suggested a modification of Nelson’s metacognitive model based on experiential learning theory that can help learners gain a better understanding of the learning process, themselves as learners, and the appropriate use of learning strategies based on the learning task and environment (see Figure 8.5). Here an individual is engaged in the process of learning something at the level of direct concrete experience. His reflective monitoring of the learning process he is going through is compared at the abstract meta-level with his idealized experiential learning model that includes concepts such as: whether he is spiraling through each stage of the learning cycle, the way his unique learning style fits with how he is being taught, and the learning demands of what he is learning. This comparison results in strategies for action that return him to the concrete learning situation through the control arrow.

Figure 8.5 Nelson’s Metacognitive Model Modified to Include the Experiential Learning Theory Learning Cycle

When individuals engage in the process of learning by reflective monitoring of the learning process they are going through, they can begin to understand important aspects of learning: how they move through each stage of the learning cycle, the way their unique learning style fits with how they are being taught, and the learning demands of what is being taught. This comparison results in strategies for action that can be applied in their ongoing learning process.

Learning Identity

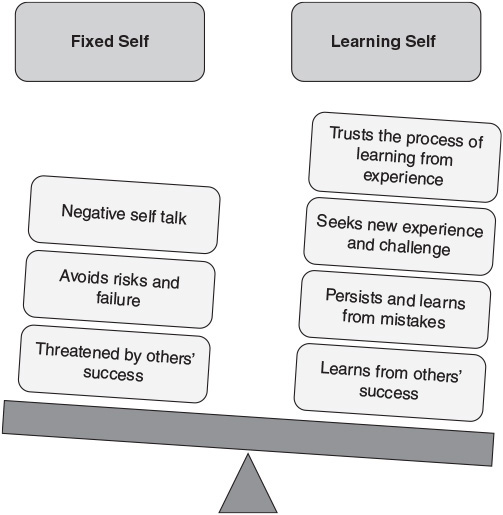

A primary metacognitive arena of deliberate learning is one’s self-image as a learner, addressing such questions as: Can I learn? How do I learn? How can I improve my learning capability? At the extreme, if a person does not believe that they can learn, they won’t. Learning requires conscious attention, effort, and “time on task.” These activities are a waste of time to someone who does not believe that they have the ability to learn. On the other hand, there are many successful individuals who attribute their achievements to a learning attitude. Oprah Winfrey, for example, has said, “I am a woman in process. I’m just trying like everybody else. I try to take every conflict, every experience, and learn from it. Life is never dull.”

People with a learning identity see themselves as learners, seek and engage life experiences with a learning attitude, and believe in their ability to learn. Having a learning identity is not an either/or proposition. A learning identity develops over time from tentatively adopting a learning stance toward life experience, to a more confident learning orientation, to a learning self that is specific to certain contexts, and ultimately to a learning self-identity that permeates deeply into all aspects of the way one lives one’s life. This progression is sustained and nurtured through growth-producing relationships in one’s life.