2. The Process of Experiential Learning

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.

—T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets*

* From Little Gidding in FOUR QUARTETS, © 1943 by T.S. Eliot; renewed 1971 by Esme Valerie Eliot. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Experiential learning theory offers a fundamentally different view of the learning process from that of the behavioral theories of learning based on an empirical epistemology or the more implicit theories of learning that underlie traditional educational methods, methods that for the most part are based on a rational, idealist epistemology. From this different perspective emerge some very different prescriptions for the conduct of education; the proper relationships among learning, work, and other life activities; and the creation of knowledge itself.

This perspective on learning is called “experiential” for two reasons. The first is to tie it clearly to its intellectual origins in the work of Dewey, Lewin, and Piaget. The second reason is to emphasize the central role that experience plays in the learning process. This differentiates experiential learning theory from rationalist and other cognitive theories of learning that tend to give primary emphasis to acquisition, manipulation, and recall of abstract symbols, and from behavioral learning theories that deny any role for consciousness and subjective experience in the learning process. It should be emphasized, however, that the aim of this work is not to pose experiential learning theory as a third alternative to behavioral and cognitive learning theories, but rather to suggest through experiential learning theory a holistic integrative perspective on learning that combines experience, perception, cognition, and behavior. This chapter will describe the learning models of Lewin, Dewey, and Piaget and identify the common characteristics they share—characteristics that serve to define the nature of experiential learning.

Three Models of the Experiential Learning Process

The Lewinian Model of Action Research and Laboratory Training

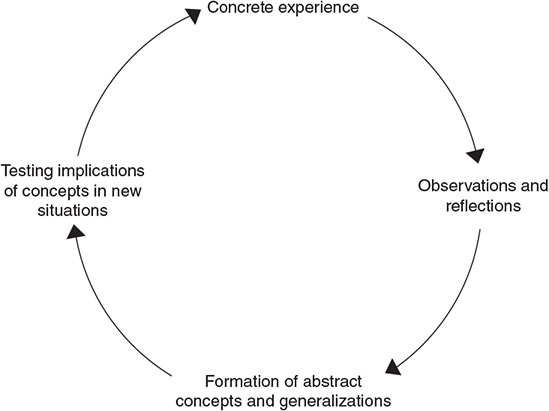

In the techniques of action research and the laboratory method, learning, change, and growth are seen to be facilitated best by an integrated process that begins with here-and-now experience followed by collection of data and observations about that experience. The data are then analyzed and the conclusions of this analysis are fed back to the actors in the experience for their use in the modification of their behavior and choice of new experiences. Learning is thus conceived as a four-stage cycle, as shown in Figure 2.1. Immediate concrete experience is the basis for observation and reflection. These observations are assimilated into a “theory” from which new implications for action can be deduced. These implications or hypotheses then serve as guides in acting to create new experiences.

Two aspects of this learning model are particularly noteworthy. First is its emphasis on here-and-now concrete experience to validate and test abstract concepts. Immediate personal experience is the focal point for learning, giving life, texture, and subjective personal meaning to abstract concepts and at the same time providing a concrete, publicly shared reference point for testing the implications and validity of ideas created during the learning process. When human beings share an experience, they can share it fully, concretely, and abstractly.

Second, action research and laboratory training are based on feedback processes. Lewin borrowed the concept of feedback from electrical engineering to describe a social learning and problem-solving process that generates valid information to assess deviations from desired goals. This information feedback provides the basis for a continuous process of goal-directed action and evaluation of the consequences of that action. Lewin and his followers believed that much individual and organizational ineffectiveness could be traced ultimately to a lack of adequate feedback processes. This ineffectiveness results from an imbalance between observation and action—either from a tendency for individuals and organizations to emphasize decision and action at the expense of information gathering, or from a tendency to become bogged down by data collection and analysis. The aim of the laboratory method and action research is to integrate these two perspectives into an effective, goal-directed learning process.

Dewey’s Model of Learning

John Dewey’s model of the learning process is remarkably similar to the Lewinian model, although he makes more explicit the developmental nature of learning implied in Lewin’s conception of it as a feedback process by describing how learning transforms the impulses, feelings, and desires of concrete experience into higher-order purposeful action.

The formation of purposes is, then, a rather complex intellectual operation. It involves: (1) observation of surrounding conditions; (2) knowledge of what has happened in similar situations in the past, a knowledge obtained partly by recollection and partly from the information, advice, and warning of those who have had a wider experience; and (3) judgment, which puts together what is observed and what is recalled to see what they signify. A purpose differs from an original impulse and desire through its translation into a plan and method of action based upon foresight of the consequences of action under given observed conditions in a certain way. . . . The crucial educational problem is that of procuring the postponement of immediate action upon desire until observation and judgment have intervened. . . . Mere foresight, even if it takes the form of accurate prediction, is not, of course, enough. The intellectual anticipation, the idea of consequences, must blend with desire and impulse to acquire moving force. It then gives direction to what otherwise is blind, while desire gives ideas impetus and momentum. [Dewey, 1938, p. 69]

Dewey’s model of experiential learning is graphically portrayed in Figure 2.2. We note in his description of learning a similarity with Lewin, in the emphasis on learning as a dialectic process integrating experience and concepts, observations, and action. The impulse of experience gives ideas their moving force, and ideas give direction to impulse. Postponement of immediate action is essential for observation and judgment to intervene, and action is essential for achievement of purpose. It is through the integration of these opposing but symbiotically related processes that sophisticated, mature purpose develops from blind impulse.

Piaget’s Model of Learning and Cognitive Development

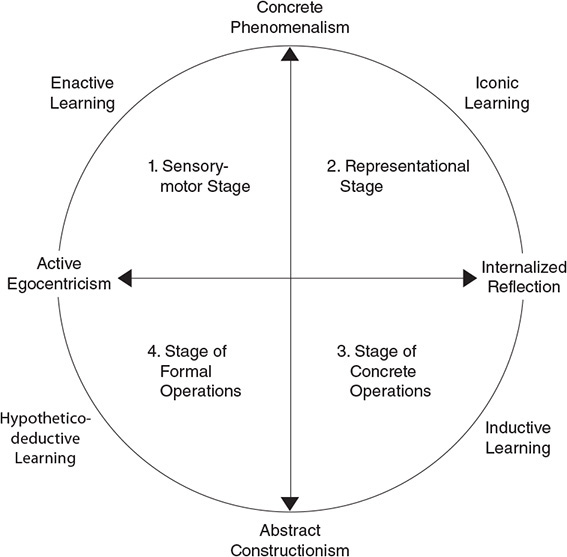

For Jean Piaget, the dimensions of experience and concept, reflection, and action form the basic continua for the development of adult thought. Development from infancy to adulthood moves from a concrete phenomenal view of the world to an abstract constructionist view, from an active egocentric view to a reflective internalized mode of knowing. Piaget also maintained that these have been the major directions of development in scientific knowledge (Piaget, 1970). The learning process whereby this development takes place is a cycle of interaction between the individual and the environment that is similar to the learning models of Dewey and Lewin. In Piaget’s terms, the key to learning lies in the mutual interaction of the process of accommodation of concepts or schemas to experience in the world and the process of assimilation of events and experiences from the world into existing concepts and schemas. Learning or, in Piaget’s term, intelligent adaptation results from a balanced tension between these two processes. When accommodation processes dominate assimilation, we have imitation—the molding of oneself to environmental contours or constraints. When assimilation predominates over accommodation, we have play—the imposition of one’s concept and images without regard to environmental realities. The process of cognitive growth from concrete to abstract and from active to reflective is based on this continual transaction between assimilation and accommodation, occurring in successive stages, each of which incorporates what has gone before into a new, higher level of cognitive functioning.

Piaget’s work has identified four major stages of cognitive growth that emerge from birth to about the age of 14–16. In the first stage (0–2 years), the child is predominantly concrete and active in his learning style. This stage is called the sensory-motor stage. Learning is predominantly enactive through feeling, touching, and handling. Representation is based on action—for example, “a hole is to dig.” Perhaps the greatest accomplishment of this period is the development of goal-oriented behavior: “The sensory-motor period shows a remarkable evolution from nonintentional habits to experimental and exploratory activity which is obviously intentional or goal oriented” (Flavell, 1963, p. 107). Yet the child has few schemes or theories into which he can assimilate events, and as a result, his primary stance toward the world is accommodative. Environment plays a major role in shaping his ideas and intentions. Learning occurs primarily through the association between stimulus and response.

In the second stage of cognitive growth (2–6 years), the child retains his concrete orientation but begins to develop a reflective orientation as he begins to internalize actions, converting them to images. This is called the representational stage. Learning is now predominantly iconic in nature, through the manipulation of observations and images. The child is now freed somewhat from his immersion in immediate experience and, as a result, is free to play with and manipulate his images of the world. At this stage, the child’s primary stance toward the world is divergent. He is captivated with his ability to collect images and to view the world from different perspectives. Consider Bruner’s description of the child at this stage:

What appears next in development is a great achievement. Images develop an autonomous status, they become great summarizers of action. By age three the child has become a paragon of sensory distractibility. He is victim of the laws of vividness, and his action pattern is a series of encounters with this bright thing which is then replaced by that chromatically splendid one, which in turn gives way to the next noisy one. And so it goes. Visual memory at this stage seems to be highly concrete and specific. What is intriguing about this period is that the child is a creature of the moment; the image of the moment is sufficient and it is controlled by a single feature of the situation. [Bruner, 1966b, p. 13]

In the third stage of cognitive growth (7–11 years), the intensive development of abstract symbolic powers begins. The first symbolic developmental stage Piaget calls the stage of concrete operations. Learning in this stage is governed by the logic of classes and relations. The child in this stage further increases his independence from his immediate experiential world through the development of inductive powers:

The structures of concrete operations are, to use a homely analogy, rather like parking lots whose individual parking spaces are now occupied and now empty; the spaces themselves endure, however, and leave their owner to look beyond the cars actually present toward potential, future occupants of the vacant and to-be-vacant spaces. [Flavell, 1963, p. 203]

Thus, in contrast to the child in the sensory-motor stage whose learning style was dominated by accommodative processes, the child at the stage of concrete operations is more assimilative in his learning style. He relies on concepts and theories to select and give shape to his experiences.

Piaget’s final stage of cognitive development comes with the onset of adolescence (12–15 years). In this stage, the adolescent moves from symbolic processes based on concrete operations to the symbolic processes of representational logic, the stage of formal operations. He now returns to a more active orientation, but it is an active orientation that is now modified by the development of the reflective and abstract power that preceded it. The symbolic powers he now possesses enable him to engage in hypothetico-deductive reasoning. He develops the possible implications of his theories and proceeds to experimentally test which of these are true. Thus his basic learning style is convergent, in contrast to the divergent orientation of the child in the representational stage:

We see, then, that formal thought is for Piaget not so much this or that specific behavior as it is a generalized orientation, sometimes explicit and sometimes implicit, towards problem solving; an orientation towards organizing data (combinatorial analysis), towards isolation and control of variables, towards the hypothetical, and towards logical justification and proof. [Flavell, 1963, p. 211]

This brief outline of Piaget’s cognitive development theory identifies those basic developmental processes that shape the basic learning process of adults (see Figure 2.3).

Characteristics of Experiential Learning

There is a great deal of similarity among the models of the learning process discussed above.1 Taken together, they form a unique perspective on learning and development, a perspective that can be characterized by the following propositions, which are shared by the three major traditions of experiential learning.

1. There are also points of disagreement, which will be explored more fully in the next chapter.

Learning Is Best Conceived as a Process, Not in Terms of Outcomes

The emphasis on the process of learning as opposed to the behavioral outcomes distinguishes experiential learning from the idealist approaches of traditional education and from the behavioral theories of learning created by Watson, Hull, Skinner, and others. The theory of experiential learning rests on a different philosophical and epistemological base from behaviorist theories of learning and idealist educational approaches. Modern versions of these latter approaches are based on the empiricist philosophies of Locke and others. This epistemology is based on the idea that there are elements of consciousness—mental atoms, or, in Locke’s term, “simple ideas”—that always remain the same. The various combinations and associations of these consistent elements form our varying patterns of thought. It is the notion of constant, fixed elements of thought that has had such a profound effect on prevailing approaches to learning and education, resulting in a tendency to define learning in terms of its outcomes, whether these be knowledge in an accumulated storehouse of facts or habits representing behavioral responses to specific stimulus conditions. If ideas are seen to be fixed and immutable, then it seems possible to measure how much someone has learned by the amount of these fixed ideas the person has accumulated.

Experiential learning theory, however, proceeds from a different set of assumptions. Ideas are not fixed and immutable elements of thought but are formed and re-formed through experience. In all three of the learning models just reviewed, learning is described as a process whereby concepts are derived from and continuously modified by experience. No two thoughts are ever the same, since experience always intervenes. Piaget (1970), for example, considers the creation of new knowledge to be the central problem of genetic epistemology, since each act of understanding is the result of a process of continuous construction and invention through the interaction processes of assimilation and accommodation (see Chapter 5, p. 153). Learning is an emergent process whose outcomes represent only historical record, not knowledge of the future.

When viewed from the perspective of experiential learning, the tendency to define learning in terms of outcomes can become a definition of nonlearning, in the process sense that the failure to modify ideas and habits as a result of experience is maladaptive. The clearest example of this irony lies in the behaviorist axiom that the strength of a habit can be measured by its resistance to extinction. That is, the more I have “learned” a given habit, the longer I will persist in behaving that way when it is no longer rewarded. Similarly, there are those who feel that the orientations that conceive of learning in terms of outcomes as opposed to a process of adaptation have had a negative effect on the educational system. Jerome Bruner, in his influential book, Toward a Theory of Instruction, makes the point that the purpose of education is to stimulate inquiry and skill in the process of knowledge getting, not to memorize a body of knowledge: “Knowing is a process, not a product” (1966, p. 72). Paulo Freire calls the orientation that conceives of education as the transmission of fixed content the “banking” concept of education:

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat. This is the “banking” concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits. They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is men themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system. For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, men cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and reinvention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other. [Friere, 1974, p. 58]

Learning Is a Continuous Process Grounded in Experience

Knowledge is continuously derived from and tested out in the experiences of the learner. William James (1890), in his studies on the nature of human consciousness, marveled at the fact that consciousness is continuous. How is it, he asked, that I awake in the morning with the same consciousness, the same thoughts, feelings, memories, and sense of who I am that I went to sleep with the night before? Similarly for Dewey, continuity of experience was a powerful truth of human existence, central to the theory of learning:

. . . the principle of continuity of experience means that every experience both takes up something from those which have gone before and modifies in some way the quality of those which come after. . . . As an individual passes from one situation to another, his world, his environment, expands or contracts. He does not find himself living in another world but in a different part or aspect of one and the same world. What he has learned in the way of knowledge and skill in one situation becomes an instrument of understanding and dealing effectively with the situations which follow. The process goes on as long as life and learning continue. [Dewey, 1938, pp. 35, 44]

Although we are all aware of the sense of continuity in consciousness and experience to which James and Dewey refer, and take comfort from the predictability and security it provides, there is on occasion in the penumbra of that awareness an element of doubt and uncertainty. How do I reconcile my own sense of continuity and predictability with what at times appears to be a chaotic and unpredictable world around me? I move through my daily round of tasks and meetings with a fair sense of what the issues are, of what others are saying and thinking, and with ideas about what actions to take. Yet I am occasionally upended by unforeseen circumstances, miscommunications, and dreadful miscalculations. It is in this interplay between expectation and experience that learning occurs. In Hegel’s phrase, “Any experience that does not violate expectation is not worthy of the name experience.” And yet somehow, the rents that these violations cause in the fabric of my experience are magically repaired, and I face the next day a bit changed but still the same person.

That this is a learning process is perhaps better illustrated by the nonlearning postures that can result from the interplay between expectation and experience. To focus so sharply on continuity and certainty that one is blinded to the shadowy penumbra of doubt and uncertainty is to risk dogmatism and rigidity, the inability to learn from new experiences. Or conversely, to have continuity continuously shaken by the vicissitudes of new experience is to be left paralyzed by insecurity, incapable of effective action. From the perspective of epistemological philosophy, Pepper (1942) shows that both these postures—dogmatism and absolute skepticism—are inadequate foundations for the creation of valid knowledge systems. He proposes instead that an attitude of provisionalism, or what he calls partial skepticism, be the guide for inquiry and learning (see Chapter 5, pp. 162–163).

The fact that learning is a continuous process grounded in experience has important educational implications. Put simply, it implies that all learning is relearning. How easy and tempting it is in designing a course to think of the learner’s mind as being as blank as the paper on which we scratch our outline. Yet this is not the case. Everyone enters every learning situation with more or less articulate ideas about the topic at hand. We are all psychologists, historians, and atomic physicists. It is just that some of our theories are more crude and incorrect than others. But to focus solely on the refinement and validity of these theories misses the point. The important point is that the people we teach have held these beliefs whatever their quality and that until now they have used them whenever the situation called for them to be atomic physicists, historians, or whatever.

Thus, one’s job as an educator is not only to implant new ideas but also to dispose of or modify old ones. In many cases, resistance to new ideas stems from their conflict with old beliefs that are inconsistent with them. If the education process begins by bringing out the learner’s beliefs and theories, examining and testing them, and then integrating the new, more refined ideas into the person’s belief systems, the learning process will be facilitated. Piaget (see Elkind, 1970, Chapter 3) has identified two mechanisms by which new ideas are adopted by an individual—integration and substitution. Ideas that evolve through integration tend to become highly stable parts of the person’s conception of the world. On the other hand, when the content of a concept changes by means of substitution, there is always the possibility of a reversion to the earlier level of conceptualization and understanding, or to a dual theory of the world where espoused theories learned through substitution are incongruent with theories-in-use that are more integrated with the person’s total conceptual and attitudinal view of the world. It is this latter outcome that stimulated Argyris and Schon’s inquiry into the effectiveness of professional education:

We thought the trouble people have in learning new theories may stem not so much from the inherent difficulty of the new theories as from the existing theories people have that already determine practices. We call their operational theories of action theories-in-use to distinguish them from the espoused theories that are used to describe and justify behavior. We wondered whether the difficulty in learning new theories of action is related to a disposition to protect the old theory-in-use. [Argyris and Schon, 1974, p. viii]

The Process of Learning Requires the Resolution of Conflicts between Dialectically Opposed Modes of Adaptation to the World

Each of the three models of experiential learning describes conflicts between opposing ways of dealing with the world, suggesting that learning results from resolution of these conflicts. The Lewinian model emphasizes two such dialectics—the conflict between concrete experience and abstract concepts and the conflict between observation and action.2 For Dewey, the major dialectic is between the impulse that gives ideas their “moving force” and reason that gives desire its direction. In Piaget’s framework, the twin processes of accommodation of ideas to the external world and assimilation of experience into existing conceptual structures are the moving forces of cognitive development. In Paulo Freire’s work, the dialectic nature of learning and adaptation is encompassed in his concept of praxis, which he defines as “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (1974, p. 36). Central to the concept of praxis is the process of “naming the world,” which is both active—in the sense that naming something transforms it—and reflective—in that our choice of words gives meaning to the world around us. This process of naming the world is accomplished through dialogue among equals, a joint process of inquiry and learning that Freire sets against the banking concept of education described earlier:

2. The concept of dialectic relationship is used advisedly in this work. The long history and changing usages of this term, and particularly the emotional and idealogical connotations attending its usage in some contexts, may cause some confusion for the reader. However, no other term expresses as well the relationship between learning orientations described here—that of mutually opposed and conflicting processes the results of each of which cannot be explained by the other, but whose merger through confrontation of the conflict between them results in a higher order process that transcends and encompasses them both. This definition comes closest to Hegel’s use of the term but does not imply total acceptance of the Hegelian epistemology (compare Chapter 5, p. 155).

As we attempt to analyze dialogue as a human phenomenon, we discover something which is the essence of dialogue itself: the word. But the word is more than just an instrument which makes dialogue possible; accordingly, we must seek its constitutive elements. Within the word we find two dimensions, reflection and action, in such radical interaction that if one is sacrificed—even in part—the other immediately suffers. There is no true word that is not at the same time a praxis. Thus, to speak a true word is to transform the world.

An unauthentic word, one which is unable to transform reality, results when dichotomy is imposed upon its constitutive elements. When a word is deprived of its dimension of action, reflection automatically suffers as well; and the word is changed into idle chatter, into verbalism, into an alienated and alienating “blah.” It becomes an empty word, one which cannot denounce the world, for denunciation is impossible without a commitment to transform, and there is no transformation without action.

On the other hand, if action is emphasized exclusively, to the detriment of reflection, the word is converted into activism. The latter—action for action’s sake—negates the true praxis and makes dialogue impossible. Either dichotomy, by creating unauthentic forms of existence, creates also unauthentic forms of thought, which reinforce the original dichotomy.

Human existence cannot be silent, nor can it be nourished by false words, but only by true words, with which men transform the world. To exist, humanly, is to name the world, to change it. Once named, the world in its turn reappears to the namers as a problem and requires of them a new naming. Men are not built in silence, but in word, in work, in action-reflection.

But while to say the true word—which is work, which is praxis—is to transform the world, saying that word is not the privilege of some few men, but the right of every man. Consequently, no one can say a true word alone—nor can he say it for another, in a prescriptive act which robs others of their words. [Freire, 1974, pp. 75, 76]

All the models above suggest the idea that learning is by its very nature a tension-and conflict-filled process. New knowledge, skills, or attitudes are achieved through confrontation among four modes of experiential learning. Learners, if they are to be effective, need four different kinds of abilities—concrete experience abilities (CE), reflective observation abilities (RO), abstract conceptualization abilities (AC), and active experimentation (AE) abilities. That is, they must be able to involve themselves fully, openly, and without bias in new experiences (CE). They must be able to reflect on and observe their experiences from many perspectives (RO). They must be able to create concepts that integrate their observations into logically sound theories (AC), and they must be able to use these theories to make decisions and solve problems (AE). Yet this ideal is difficult to achieve. How can one act and reflect at the same time? How can one be concrete and immediate and still be theoretical? Learning requires abilities that are polar opposites, and the learner, as a result, must continually choose which set of learning abilities he or she will bring to bear in any specific learning situation. More specifically, there are two primary dimensions to the learning process. The first dimension represents the concrete experiencing of events at one end and abstract conceptualization at the other. The other dimension has active experimentation at one extreme and reflective observation at the other. Thus, in the process of learning, one moves in varying degrees from actor to observer, and from specific involvement to general analytic detachment.

In addition, the way in which the conflicts among the dialectically opposed modes of adaptation get resolved determines the level of learning that results. If conflicts are resolved by suppression of one mode and/or dominance by another, learning tends to be specialized around the dominant mode and limited in areas controlled by the dominated mode. For example, in Piaget’s model, imitation is the result when accommodation processes dominate, and play results when assimilation dominates. Or for Freire, dominance of the active mode results in “activism,” and dominance of the reflective mode results in “verbalism.”

However, when we consider the higher forms of adaptation—the process of creativity and personal development—conflict among adaptive modes needs to be confronted and integrated into a creative synthesis. Nearly every account of the creative process, from Wallas’s (1926) four-stage model of incorporation, incubation, insight, and verification, has recognized the dialectic conflicts involved in creativity. Bruner (1966a), in his essay on the conditions of creativity, emphasizes the dialectic tension between abstract detachment and concrete involvement. For him, the creative act is a product of detachment and commitment, of passion and decorum, and of a freedom to be dominated by the object of one’s inquiry. At the highest stages of development, the adaptive commitment to learning and creativity produces a strong need for integration of the four adaptive modes. Development in one mode precipitates development in the others. Increases in symbolic complexity, for example, refine and sharpen both perceptual and behavioral possibilities. Thus, complexity and the integration of dialectic conflicts among the adaptive modes are the hallmarks of true creativity and growth.

Learning Is an Holistic Process of Adaptation to the World

Experiential learning is not a molecular educational concept but rather is a molar concept describing the central process of human adaptation to the social and physical environment. It is a holistic concept, much akin to the Jungian theory of psychological types (Jung, 1923), in that it seeks to describe the emergence of basic life orientations as a function of dialectic tensions between basic modes of relating to the world. To learn is not the special province of a single specialized realm of human functioning such as cognition or perception. It involves the integrated functioning of the total organism—thinking, feeling, perceiving, and behaving.

This concept of holistic adaptation is somewhat out of step with current research trends in the behavioral sciences. Since the early years of this century and the decline of what Gordon Allport called the “simple and sovereign” theories of human behavior, the trend in the behavioral sciences has been away from theories such as those of Freud and his followers that proposed to explain the totality of human functioning by focusing on the interrelatedness among human processes such as thought, emotion, perception, and so on. Research has instead tended to specialize in more detailed exploration and description of particular processes and subprocesses of human adaptation—perception, person perception, attribution, achievement motivation, cognition, memory—the list could go on and on. The fruit of this labor has been bountiful. Because of this intensive specialized research, we now know a vast amount about human behavior, so much that any attempt to integrate and do justice to all this diverse knowledge seems impossible. Any holistic theory proposed today could not be simple and would certainly not be sovereign. Yet if we are to understand human behavior, particularly in any practical way, we must in some way put together all the pieces that have been so carefully analyzed. In addition to knowing how we think and how we feel, we must also know when behavior is governed by thought and when by feeling. In addition to addressing the nature of specialized human functions, experiential learning theory is also concerned with how these functions are integrated by the person into a holistic adaptive posture toward the world.

Learning is the major process of human adaptation. This concept of learning is considerably broader than that commonly associated with the school classroom. It occurs in all human settings, from schools to the workplace, from the research laboratory to the management board room, in personal relationships and the aisles of the local grocery. It encompasses all life stages, from childhood to adolescence, to middle and old age. Therefore it encompasses other, more limited adaptive concepts such as creativity, problem solving, decision making, and attitude change that focus heavily on one or another of the basic aspects of adaptation. Thus, creativity research has tended to focus on the divergent (concrete and reflective) factors in adaptation such as tolerance for ambiguity, metaphorical thinking, and flexibility, whereas research on decision making has emphasized more convergent (abstract and active) adaptive factors such as the rational evaluation of solution alternatives.

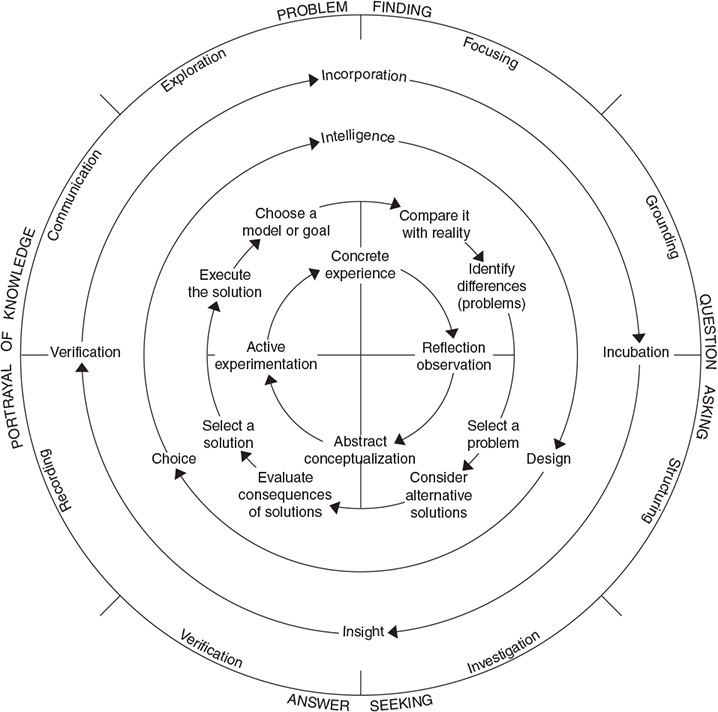

The cyclic description of the experiential learning process is mirrored in many of the specialized models of the adaptive process. The common theme in all these models is that all forms of human adaptation approximate scientific inquiry, a point of view articulated most thoroughly by the late George Kelly (1955). Dewey, Lewin, and Piaget in one way or another seem to take the scientific method as their model for the learning process; or to put it another way, they see in the scientific method the highest philosophical and technological refinement of the basic processes of human adaptation. The scientific method, thus, provides a means for describing the holistic integration of all human functions.

Figure 2.4 shows the experiential learning cycle in the center circle and a model of the scientific inquiry process in the outer circle (Kolb, 1978), with models of the problem-solving process (Pounds, 1965), the decision-making process (Simon, 1947), and the creative process (Wallas, 1926) in between. Although the models all use different terms, there is a remarkable similarity in concept among them. This similarity suggests that there may be great payoff in the integration of findings from these specialized areas into a single general adaptive model such as that proposed by experiential learning theory. Bruner’s work on a theory of instruction (1966b) shows one example of this potential payoff. His integration of research on cognitive processes, problem solving, and learning theory provided a rich new perspective for the conduct of education.

Figure 2.4 Similarities Among Conceptions of Basic Adaptive Processes: Inquiry/Research, Creativity, Decision Making, Problem Solving, Learning

When learning is conceived as a holistic adaptive process, it provides conceptual bridges across life situations such as school and work, portraying learning as a continuous, lifelong process. Similarly, this perspective highlights the similarities among adaptive/learning activities that are commonly called by specialized names—learning, creativity, problem solving, decision making, and scientific research. Finally, learning conceived holistically includes adaptive activities that vary in their extension through time and space. Typically, an immediate reaction to a limited situation or problem is not thought of as learning but as performance. Similarly at the other extreme, we do not commonly think of long-term adaptations to one’s total life situation as learning but as development. Yet performance, learning, and development, when viewed from the perspectives of experiential learning theory, form a continuum of adaptive postures to the environment, varying only in their degree of extension in time and space. Performance is limited to short-term adaptations to immediate circumstance, learning encompasses somewhat longer-term mastery of generic classes of situations, and development encompasses lifelong adaptations to one’s total life situation (compare Chapter 6).

Learning Involves Transactions between the Person and the Environment

So stated, this proposition must seem obvious. Yet strangely enough, its implications seem to have been widely ignored in research on learning and practice in education, replaced instead by a person-centered psychological view of learning. The casual observer of the traditional educational process would undoubtedly conclude that learning was primarily a personal, internal process requiring only the limited environment of books, teacher, and classroom. Indeed, the wider “real-world” environment at times seems to be actively rejected by educational systems at all levels.

There is an analogous situation in psychological research on learning and development. In theory, stimulus-response theories of learning describe relationships between environmental stimuli and responses of the organism. But in practice, most of this research involves treating the environmental stimuli as independent variables manipulated artificially by the experimenter to determine their effect on dependent response characteristics. This approach has had two outcomes. The first is a tendency to perceive the person-environment relationship as one-way, placing great emphasis on how environment shapes behavior with little regard for how behavior shapes the environment. Second, the models of learning are essentially decontextualized and lacking in what Egon Brunswick (1943) called ecological validity. In the emphasis on scientific control of environmental conditions, laboratory situations were created that bore little resemblance to the environment of real life, resulting in empirically validated models of learning that accurately described behavior in these artificial settings but could not easily be generalized to subjects in their natural environment. It is not surprising to me that the foremost proponent of this theory of learning would be fascinated by the creation of Utopian societies such as Walden II (Skinner, 1948); for the only way to apply the results of these studies is to make the world a laboratory, subject to “experimenter” control (compare Elms, 1981).

Similar criticisms have been made of developmental psychology. Piaget’s work, for example, has been criticized for its failure to take account of environmental and cultural circumstances (Cole, 1971). Speaking of developmental psychology in general, Bronfenbrenner states, “Much of developmental psychology as it now exists is the science of the strange behavior of children in strange situations with strange adults for the briefest possible periods of time” (1977, p. 19).

In experiential learning theory, the transactional relationship between the person and the environment is symbolized in the dual meanings of the term experience—one subjective and personal, referring to the person’s internal state, as in “the experience of joy and happiness,” and the other objective and environmental, as in, “He has 20 years of experience on this job.” These two forms of experience interpenetrate and interrelate in very complex ways, as, for example, in the old saw, “He doesn’t have 20 years of experience, but one year repeated 20 times.” Dewey describes the matter this way:

Experience does not go on simply inside a person. It does go on there, for it influences the formation of attitudes of desire and purpose. But this is not the whole of the story. Every genuine experience has an active side which changes in some degree the objective conditions under which experiences are had. The difference between civilization and savagery, to take an example on a large scale, is found in the degree in which previous experiences have changed the objective conditions under which subsequent experiences take place. The existence of roads, of means of rapid movement and transportation, tools, implements, furniture, electric light and power, are illustrations. Destroy the external conditions of present civilized experience, and for a time our experience would relapse into that of barbaric peoples. . . .

The word “interaction” assigns equal rights to both factors in experience—objective and internal conditions. Any normal experience is an interplay of these two sets of conditions. Taken together . . . they form what we call a situation.

The statement that individuals live in a world means, in the concrete, that they live in a series of situations. And when it is said that they live in these situations, the meaning of the word “in” is different from its meaning when it is said that pennies are “in” a pocket or paint is “in” a can. It means, once more, that interaction is going on between an individual and objects and other persons. The conceptions of situation and of interaction are inseparable from each other. An experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his environment, whether the latter consists of persons with whom he is talking about some topic or event, the subject talked about being also a part of the situation; the book he is reading (in which his environing conditions at the time may be England or ancient Greece or an imaginary region); or the materials of an experiment he is performing. The environment, in other words, is whatever conditions interact with personal needs, desires, purposes, and capacities to create the experience which is had. Even when a person builds a castle in the air he is interacting with the objects which he constructs in fancy. [Dewey, 1938, pp. 39, 42–43]

Although Dewey refers to the relationship between the objective and subjective conditions of experience as an “interaction,” he is struggling in the last portion of the quote above to convey the special, complex nature of the relationship. The word transaction is more appropriate than interaction to describe the relationship between the person and the environment in experiential learning theory, because the connotation of interaction is somehow too mechanical, involving unchanging separate entities that become intertwined but retain their separate identities. This is why Dewey attempts to give special meaning to the word in. The concept of transaction implies a more fluid, interpenetrating relationship between objective conditions and subjective experience, such that once they become related, both are essentially changed.

Lewin recognized this complexity, even though he chose to sidestep it in his famous theoretical formulation, B = f (P, E), indicating that behavior is a function of the person and the environment without any specification as to the specific mathematical nature of that function. The position taken in this work is similar to that of Bandura (1978)—namely, that personal characteristics, environmental influences, and behavior all operate in reciprocal determination, each factor influencing the others in an interlocking fashion. The concept of reciprocally determined transactions between person and learning environment is central to the laboratory-training method of experiential learning. Learning in T-groups is seen to result not simply from responding to a fixed environment but from the active creation by the learners of situations that meet their learning objectives:

The essence of this learning experience is a transactional process in which the members negotiate as each attempts to influence or control the stream of events and to satisfy his personal needs. Individuals learn to the extent that they expose their needs, values, and behavior patterns so that perceptions and reactions can be exchanged. Behavior thus becomes the currency for transaction. The amount each invests helps to determine the return. [Bradford, 1964, p. 192]

Learning in this sense is an active, self-directed process that can be applied not only in the group setting but in everyday life.

Learning Is the Process of Creating Knowledge

To understand learning, we must understand the nature and forms of human knowledge and the processes whereby this knowledge is created. It has already been emphasized that this process of creation occurs at all levels of sophistication, from the most advanced forms of scientific research to the child’s discovery that a rubber ball bounces. Knowledge is the result of the transaction between social knowledge and personal knowledge. The former, as Dewey noted, is the civilized objective accumulation of previous human cultural experience, whereas the latter is the accumulation of the individual person’s subjective life experiences. Knowledge results from the transaction between these objective and subjective experiences in a process called learning. Hence, to understand knowledge, we must understand the psychology of the learning process, and to understand learning, we must understand epistemology—the origins, nature, methods, and limits of knowledge. Piaget makes the following comments on these last points:

Psychology thus occupies a key position, and its implications become increasingly clear. The very simple reason for this is that if the sciences of nature explain the human species, humans in turn explain the sciences of nature, and it is up to psychology to show us how. Psychology, in fact, represents the junction of two opposite directions of scientific thought that are dialectically complementary. It follows that the system of sciences cannot be arranged in a linear order, as many people beginning with Auguste Comte have attempted to arrange them. The form that characterizes the system of sciences is that of a circle, or more precisely that of a spiral as it becomes ever larger. In fact, objects are known only through the subject, while the subject can know himself or herself only by acting on objects materially and mentally. Indeed, if objects are innumerable and science indefinitely diverse, all knowledge of the subject brings us back to psychology, the science of the subject and the subject’s actions.

. . . it is impossible to dissociate psychology from epistemology . . . how is knowledge acquired, how does it increase, and how does it become organized or reorganized? . . . The answers we find, and from which we can only choose by more or less refining them, are necessarily of the following three types: Either knowledge comes exclusively from the object, or it is constructed by the subject alone, or it results from multiple interactions between the subject and the object—but what interactions and in what form? Indeed, we see at once that these are epistemological solutions stemming from empiricism, apriorism, or diverse interactionism. . . . [Piaget, 1978, p. 651]

It is surprising that few learning and cognitive researchers other than Piaget have recognized the intimate relationship between learning and knowledge and hence recognized the need for epistemological as well as psychological inquiry into these related processes. In my own research and practice with experiential learning, I have been impressed with the very practical ramifications of the epistemological perspective. In teaching, for example, I have found it essential to take into account the nature of the subject matter in deciding how to help students learn the material at hand. Trying to develop skills in empathic listening is a different educational task, requiring a different teaching approach from that of teaching fundamentals of statistics. Similarly, in consulting work with organizations, I have often seen barriers to communication and problem solving that at root are epistemologically based—that is, based on conflicting assumptions about the nature of knowledge and truth.

The theory of experiential learning provides a perspective from which to approach these practical problems, suggesting a typology of different knowledge systems that results from the way the dialectic conflicts between adaptive modes of concrete experience and abstract conceptualization and the modes of active experimentation and reflective observation are characteristically resolved in different fields of inquiry (compare Chapter 5). This approach draws on the work of Stephen Pepper (1942, 1966), who proposes a system for describing the different viable forms of social knowledge. This system is based on what Pepper calls world hypotheses. World hypotheses correspond to metaphysical systems that define assumptions and rules for the development of refined knowledge from common sense. Pepper maintains that all knowledge systems are refinements of common sense based on different assumptions about the nature of knowledge and truth. In this process of refinement he sees a basic dilemma. Although common sense is always applicable as a means of explaining an experience, it tends to be imprecise. Refined knowledge, on the other hand, is precise but limited in its application or generalizability because it is based on assumptions or world hypotheses. Thus, common sense requires the criticism of refined knowledge, and refined knowledge requires the security of common sense, suggesting that all social knowledge requires an attitude of partial skepticism in its interpretation.

Summary: A Definition of Learning

Even though definitions have a way of making things seem more certain than they are, it may be useful to summarize this chapter on the characteristics of the experiential learning process by offering a working definition of learning.3 Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. This definition emphasizes several critical aspects of the learning process as viewed from the experiential perspective. First is the emphasis on the process of adaptation and learning as opposed to content or outcomes. Second is that knowledge is a transformation process, being continuously created and recreated, not an independent entity to be acquired or transmitted. Third, learning transforms experience in both its objective and subjective forms. Finally, to understand learning, we must understand the nature of knowledge, and vice versa.

3. From this point on, I will drop the modifier “experiential” in referring to the learning process described in this chapter. When other theories of learning are discussed, they will be identified as such.

Update and Reflections

The Learning Cycle and the Learning Spiral

The people who ‘learn by experience’ often make great messes of their lives, that is, if they apply what they have learned from a past incident to the present, deciding from certain appearances that the circumstances are the same, forgetting that no two situations can ever be the same. . . . All that I am, all that life has made me, every past experience that I have had—woven into the tissue of my life—I must give to the new experience. That past experience has indeed not been useless, but its use is not in guiding present conduct by past situations. We must put everything we can into each fresh experience, but we shall not get the same things out which we put in if it is a fruitful experience, if it is part of our progressing life . . . We integrate our experience, and then the richer human being that we are goes into the new experience; again we give ourself and always by giving rise above the old self.

—Mary Parker Follett, 1924, pp. 136–137

Chapter 2 defines the experiential learning cycle particularly as represented in the theories of Lewin and Dewey. It further suggests that Piaget’s more linear model of development is consistent with the learning cycle adding his two dialectical dimensions of concrete phenomenalism/abstract constructionism and active ego-centrism/internalized reflection.

The learning cycle and the concept of learning style are the most widely known and used concepts in experiential learning theory; although there is considerable confusion and misunderstanding of the concepts often resulting from being taken out of the context of the wider experiential learning theory framework. This update will address these issues with regard to the learning cycle (the Chapter 4 update will do so for the concept of learning style).

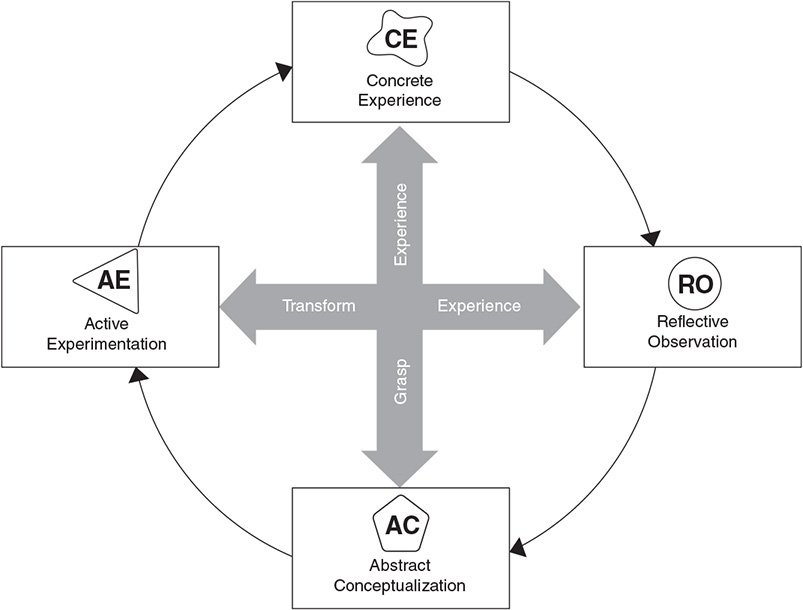

Understanding the Learning Cycle

In its most current statement (Kolb and Kolb, 2013) experiential learning theory is described as a dynamic view of learning based on a learning cycle driven by the resolution of the dual dialectics of action/reflection and experience/abstraction. Learning is defined as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (Chapter 2, p. 49). Knowledge results from the combination of grasping and transforming experience. Grasping experience refers to the process of taking in information, and transforming experience is how individuals interpret and act on that information. The experiential learning theory learning model portrays two dialectically related modes of grasping experience—Concrete Experience (CE) and Abstract Conceptualization (AC)—and two dialectically related modes of transforming experience—Reflective Observation (RO) and Active Experimentation (AE). Learning arises from the resolution of creative tension among these four learning modes. This process is portrayed as an idealized learning cycle or spiral where the learner “touches all the bases”—experiencing (CE), reflecting (RO), thinking (AC), and acting (AE)—in a recursive process that is sensitive to the learning situation and what is being learned. Immediate or concrete experiences are the basis for observations and reflections. These reflections are assimilated and distilled into abstract concepts from which new implications for action can be drawn. These implications can be actively tested and serve as guides in creating new experiences (see Figure 2.5).

This cycle of learning has been widely used and adapted in the design and conduct of countless educational programs. A Google image search of “learning cycle” produces a seemingly endless array of reproductions and variations of the cycle from around the world.

While I have been personally gratified by the scholarship and pragmatic utility generated by the concept, others have been alarmed and concerned by its apparent simplicity and failure to “problematize” experience. Reijo Miettinen asks, “Why is this conception so popular within adult education? . . . Perhaps the idea of experiential learning forms an attractive package for adult educators. It combines spontaneity, feeling, and deep individual insights with the possibility of rational thought and reflection. It maintains the humanistic belief in every individual’s capacity to grow and learn, so important for the concept of lifelong learning. It comprises a positive ideology that is evidently important for adult education. However, I fear that the price of this package for adult education and research is high . . . the belief in an individual’s capabilities and his individual experience leads us away from the analysis of cultural and social conditions of learning that are essential to any serious enterprise of fostering change and learning in real life.” (2000, pp. 70–71). In an editorial in the Adult Education Quarterly, the editors echo this concern about the “unquestioned notion of experience in the pragmatic tradition”: “Kolb’s learning cycle has become as ubiquitous as Maslow’s hierarchical triangle. This is not just unfortunate, but limiting, because it restricts the way we see and understand experience which thus limits the way we can learn in-from-to experience” (Wilson and Hayes, 2002, p. 174).

In a way I also, on occasion, have been disturbed by oversimplified interpretations and applications of the learning cycle. Many times this seems to be because the cycle has been taken out of the wider context of experiential learning theory, and/or I have failed to explain my perspective adequately. The Adult Education Quarterly editors should not be worried, for among the thousands of scholarly articles published about experiential learning theory, I have found over 50 that have examined and critiqued experiential learning theory from their perspective as well as others. The views expressed represent a wide range of opinion and theoretical orientations, sometimes contradicting each other. Collectively they open a valuable conversation about the future of experiential learning research and practice. Experiential Learning was not the first word on the subject (as we have seen in Chapter 1 and its update), and it certainly was not intended to be the last. With the help of the thoughtful critiques I will address some of these views from my perspective today.

The learning cycle describes an individual model of learning that ignores the historical, cultural, and social context of learning. Some critics (Hopkins, 1993; Seaman, 2008; Reynolds, 1997, 1998; Michelson, 1997, 1998, 1999; Fenwick, 2000, 2003) along with Miettinen and the journal editors have found the learning cycle and experiential learning theory in general to be too psychological and individualistic. Reynolds, for example, says experiential learning theory “is highly individualizing, and its psychological perspective, whether orthodox or humanist, ignores or downgrades the social context . . . being psychological in conception it takes little or no account of the meaning of difference in terms of social or political process” (1997, p. 128).

Michelson poses her critique from a broader historical perspective suggesting:

“that mainstream theories of experiential learning . . . rest on an interiorized subjectivity that emerged only with the Enlightenment, when inner consciousness came to be seen as a ‘space’ to be explored, a realm separate from and discontinuous with any external reality . . . (and) reproduce the Enlightenment relationship between psychic and cognitive interiority and political and economic agency. Just as in the writings of Locke, the autonomy of privatized inner experience is what grounds our rights and liberties under the social contract: according to David Kolb, the fact that we are ‘still learning from our experience’ means that ‘we are free’ and able to ‘chart the course of our own destiny’ (Kolb, 1984, p. 109). Indeed, the conjoining of privatized experience with the claims to political agency is made explicit in the quotation by John Dewey with which Kolb (1984, p. 1) begins Experiential Learning: ‘The modern discovery of inner experience, of a realm of purely personal events that are always at the individual’s command and that are his [sic] exclusively . . . is also a great and liberating discovery. It implies a new worth and sense of dignity in human individuality’”(1999, p. 144).

Agreeing with Dewey, my aim for experiential learning theory was to create a model for explaining how individuals learn and to empower learners to trust their own experience and gain mastery over their own learning. My psychological training as a personality theorist has made me a great advocate of individuality. Each of us is deeply unique, and we have an imperative to embrace and express that uniqueness, for the good of ourselves and for the world. Martha Graham said it well, “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening, that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique, and if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and will be lost.” Individuality is different than individualism, which is egocentric. In individualism, “the individual is not viewed as an integral part of his or her social world; the feeling of belonging to a group is not seen as giving life purpose and direction. Rather society is viewed as either corrupting or civilizing our basically asocial nature” (Guisinger and Blatt, 1994, p. 105).

Individuality and relatedness in experiential learning theory are poles of a fundamental dialectic of development, “. . . the capacities to form a mutual relationship with another, to participate in society, and to be dedicated to one’s own self-interest and expression emerge out of the integration and consolidation of individuality and relatedness in the development of a self-identity . . .” (Guisinger and Blatt, 1994, pp. 108–109). Similarly, Susanne Cook-Greuter (1999) and David Bakan (1966) argue that there is a human need to fulfill the double goals of autonomy (differentiation, independence, mastery) and homonomy (integration, participation, belonging).

It is true that Experiential Learning is not a discourse on social and political factors that influence what people learn and believe in the tradition of critical theory. This was not my purpose, though I believe that experiential learning theory is not incompatible with these approaches. Both views together enhance our full understanding of experiential learning. Among the experiential learning theory foundational scholars, Dewey and Follett were leaders in the Progressive movement, and Freire’s life was one of struggle for social justice in his country. Vygotsky’s work is foundational for activity theory and social constructivism. From their contributions, experiential learning theory has much to offer critical cultural theory in pedagogy, feminist theory, post-structural scholarship, social constructionism, post-colonial, and indigenous culture studies.

The learning cycle is constructivist and cognitivist. These terms have been used to characterize the learning cycle as portraying learning in a way that separates the individual from the environment. Fenwick defines constructivism as a process where “the learner reflects on lived experience and then interprets and generalizes this experience to form mental structures. These structures are knowledge, stored in memory as concepts that can be represented, expressed, and transferred to new situations (2000, p. 248). . . . In the constructivist view, the learner is still viewed as fundamentally autonomous from his or her surroundings. The learner moves through context, is in it and affected by it, but the learner’s meanings still exist in the learner’s head and move with the learner from one context to the next. Knowledge is thus a substance, a third thing created from the learner’s interaction with other actors and objects and bounded in the learner’s head. Social relations of power exercised through language or cultural practices are not theorized as part of knowledge construction” (2000, p. 250).

Michelson seems to ignore the holistic characteristic of experiential learning theory (Chapter 2, pp. 43–45) when she argues that the constructivism of the learning cycle portrays learning as occuring in the mind alone, “. . . the mind accesses information about the world and uses that information to produce learning. The body functions essentially as sensate medium and testing instrument, while the emotions and the spirit do not participate at all” (1997, p. 48).

Constructivism, of course, originated in the work of Piaget and Vygotsky whose ideas play a big role in experiential learning theory. However, I modified the constructivist view in significant ways (see Chapter 3, p. 66; Chapter 6, pp. 201–205). Holman, Pavlica, and Thorpe use the somewhat pejorative term “cognitivist” preferred by critical theorists and social constructionists to at first acknowledge these modifications and then discount them, “KELT is rarely linked to, and often considered fundamentally different from cognitive learning schools. Indeed Kolb himself has sought to distance his theory from a strict Paigetiatian cognitivism by stressing its roots in pragmaticism and social action theories. . . . However, while KELT may have its roots in Dewey and Lewin, Kolb’s reworking of these and other theorists upon whom he draws embeds his work in a number of cognitivist assumptions which relate to the nature of self and thought . . . to produce a work that is fundametally cognitivist” (1997, p. 136). The “cognitivist assumptions” they cite include the person is independent of the social/historical/cultural context, representational thinking and mental process can be studied in isolation.

What I think the critics from this perspective have missed in their reading of Experiential Learning is the posited transactional relationship of the individual and the social environment. The Gestalt foundational scholars, Kurt Lewin and Mary Parker Follett, William James (radical empiricism), and John Dewey (depiction of the difference between interaction and transaction), all portray an embedded and integrated view of the individual and the world that stands in contrast to Piaget’s description of an individual developmental process that is universal across contexts (see Chapter 6, pp. 201–205). In the section describing learning as a transaction between the person and environment in Chapter 2 (pp. 45–48), I summarize the issue: “The word transaction is more appropriate than interaction to describe the relationship between the person and the environment in experiential learning theory because the connotation of interaction is somehow too mechanical, involving unchanging separate identities that become intertwined but retain their separate identities . . . The concept of transaction implies a more fluid interpenetrating relationship between objective conditions and subjective experience, such that once they become related, both are essentially changed.” (See “The Learning Spiral” section below.) Mary Parker Follett describes this process which she calls “circular response” in human relationships: “Through circular response we are creating each other all the time . . . Accurately speaking the matter cannot be expressed by the phrase used above, I-plus-you meeting you-plus-me. It is I plus the-interweaving-between-you-and-me meeting you plus the-interweaving-between-you-and-me, etc., etc. ‘I’ can never influence ‘you’ because you have already influenced me; that is, in the very process of meeting, by the very process of meeting, we both become something different” (1924, pp. 62–63).

The Experiential Learning Cycle is an oversimplified view of learning describing a mechanical step-by-step process that distorts both learning and experience. Seaman, who calls for an end to the “Learning Cycles Era,” suggests that “the definition of experiential learning as an orderly series of steps is either false . . . or represents only a narrow type of experiential learning. . . . The intent of this article is not to suggest that the routine patterns used in different experiential practices . . . should be abandoned. This approach has unquestionably served many practitioners throughout the years. Rather, this article has argued against the claim that experiential learning can be fundamentally understood as equivalent to these patterns” (2008, p. 15). Others have also viewed the distinct sequential stages of the learning cycle as an oversimplified description of learning (DiCiantis and Kirton, 1996; Holman, 1997; Smith, 2010; Jarvis, 1987, 1995).

As I described in the introduction, I, too, initially used the learning cycle in a simplistic way as a pragmatic tool to organize learning events. It was only after I saw the resulting rich experience and learning that was created for learners that I began to search for a theoretical explanation of the learning process in the work of the experiential learning theory foundational scholars. The concept of learning style was created later, based on the emerging theory of experiential learning. Our observations of different styles of learning were in fact different ways of engaging the learning cycle (Kolb and Kolb, 2013a). The insight that led me to think that the cycle of learning from experience was more complex was the identification of the two dialectically related dimensions of grasping experience via concrete experience and abstract conceptualization and transforming experience via active experimentation and reflective observation. I first noticed the dimensions in the theories of Lewin, Dewey, Piaget, and Freire and developed them further with the aid of Jung’s introversion/extraversion transformation dialectic and with James’ apprehension/comprehension grasping dialectic. (For my explanations of these dialectic dimensions and their relationship to the learning process, see Chapter 2, pp. 40–42; Chapter 3, pp. 65–86; Chapter 5, pp. 159–163; Chapter 6, pp. 199, 210–215; and Chapter 8, pp. 328–333.)

Introduction of the dialectic dimensions confuses structure and process. However, for Hopkins, an avid phenomenologist, the introduction of the dialectic structural analysis to the stage model doesn’t work: “Kolb’s theory as a formalistic reification of experiential process cannot withstand phenomenological reflection . . .” (1993, p. 54) He argues with Nelson and Grinder (1985) that my combination of structure and process doesn’t work because it fails to “untangle” the relation between the two. Miettinen agrees that the stage model is not helped by the introduction of the dialectic dimensions: “The phases remain separate. . . . Kolb does not present any concept that would connect the phases to each other. . . . Kolb continuously speaks about ‘dialectic tension’ between experiential and conceptual. However, he resolves the tension simply by taking both as a separate phase to his model. There is surely no dialectics in this. Dialectic logic would show how these two are indispensable related to each other and are determined through other” (2000, p. 61).

For me, these dialectic opposites opened a space for experiencing that embraced the multidimensional aspects of experience and all modes of the learning cycle as described in James’ radical empiricism and in phenomenology (Introduction, pp. xxii–xxiii). Experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting are not separate independent entities but inextricably related to one another in their dialectic opposition. They are mutually determined and in dynamic flux. The dialectic dimensions also formed the basis of the concept of learning style; a habit of learning that is formed when one or more of the learning modes is preferred over others to shape experience, resulting in a constriction and limiting of the experiencing space around the mode(s). The ranking format of the Learning Style Inventory was chosen precisely to describe the interdependent holistic relationship among the modes (generating considerable controversy about the resulting ipsativity of the data, to be discussed later in the Chapter 4 update). Miettinen has it backwards when he says, “The separateness of the phases and corresponding modes of learning are also based on the fact that the model is constructed to substantiate the validity of the learning style inventory. The construction of distinct styles makes it necessary to postulate distinct modes of adaptation. In this way the technological starting point partly dictates the mode and content of the ‘theoretical’ model” (2000, p. 61).

The conflicts between opposing dialectics help explain the dynamic nature of experience (Bassechess, 1984, 2005): as in Piaget’s ongoing to-and-fro between assimilating experiences into existing concepts and accommodation of concepts to new experiences, or in Dewey’s recursive uniting of desire and idea to form purpose. There may be pragmatic utility in organizing education around an idealized cycle that begins with concrete experience, is followed by reflection alone or with others, introducing concepts and theory to organize and conclude the meaning of the experience, and then concludes with action to test the conclusions in new experience. However, as learners, our experiences are seldom so orderly. In one moment we may be lost in thought only to be jolted to awareness of a dramatic event, sparking immediate action or cautious observation depending on our habit of learning. Our learning style may dictate where we begin a process of learning and/or the context may shape it. Learning usually does not happen in one big cycle but in numerous small cycles or partial cycles. Thinking and reflection can continue for some time before acting and experiencing. Experiencing and reflecting can also continue through much iteration before concluding in action.

The primary importance of reflection for learning and development is not emphasized. A number of important experiential learning theorists such as David Boud (Boud, Keogh, and Walker, 1985; Boud and Miller, 1996), Jack Mezirow (1990, 1996), Stephen Brookfield (1987, 1995), and Donald Schon (1983) place reflection as the primary source of the transformation that leads to learning and development. Unlike these advocates of reflective practice, reflection in experiential learning theory is not the sole determinant of learning and development but is one facet of a holistic process of learning from experience that includes experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting. As we have seen, the shock of direct concrete experience may be necessary to initiate it. Reflection in isolation can become retroflection, a turning in on itself that isolates the learners in their own self-confirming world unable to reach conclusions or test them in action. When reflection is structured in a critical theory framework, Kegan (1994) and Kayes (2002) have argued that it can have dysfunctional effects. “Critical approaches may help individuals gain insight into their social context, but this often leaves the individual stranded in a complex world without the appropriate tools to reorder this complexity. The newly ‘emancipated’ may experience more repression that ever as they become stripped of their own capacity to respond to new, more challenging demands that come with emancipation” (Kayes, 2002, p. 142).

Mary Parker Follett (1924) stresses the intimate relationship between experience, action, and reflection. “We often hear people talk of the interpretation of experience as if we first had an experience and then interpreted it, but there is a closer and different connection between these two; my behavior in that experience is as much a part of my interpretation as my reflection upon it afterwards; my intellectual, post-facto, reflective interpretation is only part of the story.” Reflection also requires cognitive complexity and the capacity for critical thinking, the abstract conceptualization phase of the learning cycle. Deep reflection requires a rich and integrated cognitive structure to be able to adopt different perspectives and analytical strategies.

In experiential learning theory reflection is defined as the internal transformation of experience. This broad definition includes several more specific reflective processes that vary by learning style and developmental level. The three reflective learning styles in the KLSI 4.0 (Kolb and Kolb, 2011, 2013) define a continuum of reflection. The Imagining style is focused on iconic transformation of images that are still somewhat immersed in the concrete experiences of sensation and affect. At the other extreme is the Analyzing style, where reflection is more systematic manipulation of abstract symbols fully independent of experience and context. In between, the Reflecting style explores deeper meanings to integrate image and symbol.

The three stages of development in the experiential learning theory developmental frame work—acquisition, specialization, and integration each are characterized by different reflective processes. These processes have been articulated most clearly by Humphrey (2009) as reflection, reframing and reform.

![]() Reflection. Reflection at this elementary level constitutes spontaneous reflective observation of direct experiences. In Zull’s depiction of experiential learning and the brain, direct sensory experiences are connected to memories, images and emotions in the temporal integrative cortex.

Reflection. Reflection at this elementary level constitutes spontaneous reflective observation of direct experiences. In Zull’s depiction of experiential learning and the brain, direct sensory experiences are connected to memories, images and emotions in the temporal integrative cortex.

![]() Reframing. Dewey distinguished what he called casual spontaneous reflection at the first level from a more intense reflective process he called critical reflection (1933, p. 14). Critical reflection entails an examination and critique of reflective observations from specialized theories and analytic frameworks. The framework is used to examine assumption and reframe issues, adopting alternative perspectives that produce a deeper understanding. Critical reflection is often associated with critical theory (Brookfield, 1995, 2009) and post-structural deconstruction (Fook, 2002), frameworks for unmasking power manipulations and hidden forms of social control. However, other disciplined systems of inquiry, for example, aesthetics (Dewey, 1934; Rasanen, 1997), can also offer possibilities for reframing that produce creative new perspectives.