5. The Structure of Knowledge

Experience is not a veil that shuts off man from nature, it is a means of penetrating continually further into the heart of nature.

—John Dewey

No account of human learning could be considered complete without an examination of culturally accumulated knowledge, its nature and organization, and the processes whereby individual learners contribute to and partake of that knowledge. Individual learning styles are shaped by the structure of social knowledge and through individual creative acts; knowledge is formed by individuals. To understand learning fully, we must understand the nature and forms of human knowledge and the processes whereby this knowledge is created and recreated. Piaget, in the conclusion to his 1970 book, Genetic Epistemology, describes three approaches to learning and knowledge creation and their relation to learning from experience:

These few examples may clarify why I consider the main problem of genetic epistemology to be the explanation of the construction of novelties in the development of knowledge. From the empiricist point of view, a “discovery” is new for the person who makes it, but what is discovered was already in existence in external reality and there is therefore no construction of new realities. The nativist or apriorist maintains that the forms of knowledge are predetermined inside the subject and thus again, strictly speaking, there can be no novelty. By contrast, for the genetic epistemologist, knowledge results from continuous construction, since in each act of understanding, some degree of invention is involved; in development, the passage from one stage to the next is always characterized by the formation of new structures which did not exist before, either in the external world or in the subject’s mind. [Piaget, 1970a, p. 77]

The empiricist, apriorist (rationalist), and genetic-epistemology (interactionist) perspectives on the acquisition of knowledge have defined epistemological debates in Western philosophy since the classical Greek philosophers. In the seventeenth century came the first challenge to the dogma of religious and political authority. The unitary worldview of medieval scholasticism that had dominated the Christian world up until that time gave way to the development of rational and later, empirical concepts that made possible control and mastery of the material world. In the seventeenth century, knowledge was thought to be accessible to the mind alone through rational analysis and introspection. The rationalist philosophers—most notably Descartes, Spinoza, and Libnetz—posed the thesis that truth was to be discovered by use of the tools of logic and reason. Ideas were real and a priori to the empirical world. Since experiences were merely reflections of ideal forms, it was the ideal forms in the mind that gave meaning to experiences in the world. As Descartes put it:

[God] laid down these laws in nature just as a king lays down laws in his kingdom. There is no single one that we cannot understand if our minds turn to consider it. They are all inborn in our minds just as a king would imprint his laws on the hearts of his subjects if he had enough power to do so. [Cited in Frankfurt, 1977, p. 36]

The eighteenth century gave rise to the antithesis of rationalism—empiricism. According to the empiricist philosophers—Locke, Hobbes, and others—knowledge was to be found in the accumulated associations of our sense impressions of the world around us. The mind was a tabula rasa, recording these accumulated sense impressions but making no contribution of its own save its capacity to recognize “substance.” Truth was to be found in careful observation of the world, a notion that gave rise to a burgeoning of scientific investigation in the eighteenth century.

The nineteenth century saw a synthesis of the rationalist and empiricist positions in the critical idealism of Kant, the first of the interactionist epistemologists. For Kant, the mind possessed a priori equipment that enabled it to interpret experience—specifically, equipment to locate forms in time and space and equipment to understand order and uniformity. Thus, the laws of geometry and logic were considered to be beyond experience and essential for interpreting it. Truth in critical idealism was the product of the interaction between the mind’s forms and the material facts of sense experience.

Apprehension vs. Comprehension—A Dual-Knowledge Theory

This brief overview of the history of epistemological philosophy is perhaps sufficient to frame the contribution of experiential learning theory to the question of how knowledge is acquired. A moment’s reflection on the experiential learning cycle (see Figure 3.1) will suffice to illustrate the limitations of either the rationalist or the empiricist philosophies alone as an epistemological foundation for experiential learning. As we have seen in Chapter 3, experiential learning is based on a dual-knowledge theory: the empiricists’ concrete experience, grasping reality by the process of direct apprehension, and the rationalists’ abstract conceptualization, grasping reality via the mediating process of abstract conceptualization. We are thus left with Piaget in the interactionist position.

The interactionist epistemology of experiential learning theory, however, is different in some significant ways from the Piagetian interactionism of genetic epistemology. As has been suggested, Piaget’s interactionism is decidedly rationalist in spirit. Consider, for example, his explanation of how it is that mathematical formulations have consistently anticipated subsequent empirical findings:

This harmony between mathematics and physical reality cannot in positivist fashion be written off as simply the correspondence of a language with the object it designates. . . . Rather it is a correspondence of human operations with those of object operators, a harmony, then, between this particular operator—the human being as body and mind—and the innumerable operators in nature—physical objects at their several levels. Here we have remarkable proof of that preestablished harmony among windowless monads of which Liebnitz dreamt. . . the most beautiful example of biological adaptation that we know of. [Piaget, 1970a, pp. 40–41]

Substitute the processes of “biological adaptation” for “imprinting of his laws on our hearts,” and the “human operations” of the mind according to Piaget are nearly identical with the “inborn laws” of Descartes in the quote just cited. For both men, the powers of the mind are directly connected with the structure of reality. This rationalist orientation is reflected in the predominant position of action in Piaget’s theory about how knowledge is created. For him, sensations and perceptions are only the starting point of knowing; it is the organization and transformation of these sensations through action, most particularly internalized actions or thoughts, that creates knowledge. Knowledge then, for Piaget, is the progressive internalization of the action transformations through which we construct reality—a decidedly rationalist interactionism in which sensation (or knowing by apprehension) is secondary.

The interactionism of experiential learning theory places knowing by apprehension on an equal footing with knowing by comprehension, resulting in a stronger interactionist position, really a transactionalism, in which knowledge emerges from the dialectic relationship between the two forms of knowing.1 This dialectic relationship is not the Kantian dialectic, in which thesis and antithesis stand only in logical contradiction, but the Hegelian dialectic, in which contradictions and conflicts are borne out of both logic and emotion in a thesis and antithesis of mutually antagonistic convictions.

1. We focus in this chapter on the prehension dimension of apprehension and comprehension rather than the transformation dimension of intention and extension, because the prehension dimension describes the current state of our knowledge of the world—the content of knowledge, if you will—whereas the transformation dimension describes the rates or processes by which that knowledge is changed. Although both content and process are legitimate aspects of structure, it is the content of knowledge and its form that have been the primary concern of epistemology, Piaget’s emphasis on behavioral transformation notwithstanding. This is in a sense a convenience of exposition, since enduring effects of transformation processes will be represented in the content of knowledge just as the rate of water flowing into a tub is reflected in the level of water in the tub.

To better understand the nature of this dialectic, let us examine the nature of the two knowing processes whose opposition fuels it. To begin with, knowing by apprehension is here-and-now. It exists only in a continuously unfolding present movement of apparently limitless depth wherein events are related via synchronicity—that is, a patterned interrelationship in the moment (compare Jung, 1960). It is thus timeless—at once instantaneous and eternal, the dynamic form of perceiving that Werner calls physiognomic (see Chapter 6, p. 204). Comprehension, on the other hand, is by its very nature a record of the past that seeks to define the future; the concept of linear time is perhaps its most fundamental foundation, underlying all concept of causality. As Hume pointed out, the mind cannot learn causal connections between events by experience alone (apprehension). All we learn through apprehension is that event B follows event A. There is nothing in the sense impression to indicate that A causes B. This judgment of causality is based on inferences from our comprehension of A and B.

The interplay between these two forms of knowing in the creation of knowledge is illustrated in what has been a difficult circular-argument problem in physics—the fact that speed is defined by using time and time is measured by speed. In classical mechanics, speed and time are coequal, since speed is defined as the relation between traveled space and duration. In relativistic mechanics, however, speed is more elementary, since it has a maximum velocity (the speed of light). This formulation led Einstein to ask Piaget, when they met in 1928, to investigate from the psychological viewpoint questions as to whether there was a sense of speed that was independent of time and that was more fundamental (acquired earlier). What Piaget and his associates found (Piaget, 1971) was that speed is the more basic notion, based on perception (apprehension), whereas time is a more inferential, complex construct (based on comprehension). Their experiments involved asking children to describe a moving object that passed behind nine vertical bars. Seventy to 80 percent of the subjects reported movement acceleration when the object passed behind the bars. Piaget’s conclusion was that following the moving object with one’s eyes was handicapped in the barred sections by momentary fixations on the bars, causing an impression of greater speed in the moving object. The apprehension of speed thus seems to be based on the muscular effort expended in attending to a moving object. The comprehension of time, however, occurs later developmentally and is much more complex. The apparent circularity of space/time equations in physics therefore appears to be psychologically rooted in the dialectic relationships of knowing speed by apprehension and time by comprehension.

A second difference between knowing by apprehension and knowing by comprehension is that apprehension is a registrative process transformed intentionally and extensionally by appreciation, whereas comprehension is an interpretive process transformed intentionally and extensionally by criticism. Michael Polanyi describes this difference in his comparison of articulate form (comprehension-based knowledge) and tacit knowledge (based on apprehension):

Where there is criticism, what is being criticized is, every time, the assertion of an articulate form. . . . The process of logical inference is the strictest form of human thought, and it can be subjected to severe criticism by going over it stepwise any number of times. Factual assertations and denotations can also be examined critically, although their testing cannot be formalized to the same extent.

In this sense just specified, tacit knowing cannot be critical . . . systematic forms of criticism can be applied only to articulate forms which you can try out afresh again and again. We should not apply, therefore, the terms critical or uncritical to any process of tacit thought by itself any more than we would speak of the critical or uncritical performance of a high jump or a dance. Tacit acts are judged by other standards and are to be regarded accordingly as a-critical. [Polanyi, 1958, p. 264]

The enduring nature of the articulate forms of comprehensive knowledge makes it possible to analyze, criticize, and rearrange these forms in different times and contexts. It is through such critical activity that the network of comprehensive knowledge is refined, elaborated on, and integrated. Any attempt to be critical of knowledge gained through apprehension, however, only destroys that knowledge. Criticism requires a reflective, analytic, objective posture that distances one from here-and-now experience; the here-and-now experience in fact becomes criticizing, replacing the previous immediate apprehension. Since I am an avid golfer, this fact has been illustrated in my experience many times. In approaching a green to putt the ball, I note the distance of the ball from the hole, the slope of the green, the length and bend of the grass, how wet or dry it is, and other relevant factors. I attempt to attend to these factors without analyzing them, for when my mind is dominated by an analytic formula for hitting the ball (for instance, hit it harder because it’s wet), the putt invariably goes awry. What seems to work better is an appreciation of the total situation (the situation being defined by my previous comprehension of relevant aspects to attend to) in which I, the putter, ball, green, and hole are experienced holistically (no pun intended; compare Polanyi, 1966, pp. 18–19).

Much can be said about the process and method of criticism; indeed, most scholarly method is based on it. The process of appreciation is less recognized and understood. Thus, it is worth describing in some detail the character of appreciation. First, appreciation is intimately associated with perceptual attention processes. Appreciation is largely the process of attending to and being interested in aspects of one’s experience. We notice only those aspects of reality that interest us and thereby “capture our attention.” Interest is the basic fact of mental life and the most elementary act of valuing. It is the selector of our experience. Appreciation involves attending to and being interested in our apprehensions of the world around us. Such attention deepens and extends the apprehended experience. Vickers, along with Zajonc (see Chapter 3), suggests that such appreciative apprehensions precede judgments of fact; in other words, that preferences preceded inferences:

For even that basic discriminatory judgment “this” is a “that” is no mere finding of fact, it is a decision to assimilate some object of attention, carved out of the tissue of all that is available to some category to which we have learned, rightly or wrongly, that it is convenient to assimilate such things. [Vickers, 1968, pp. 139–140]

A second characteristic of appreciation, already alluded to, is that it is a process of valuing. Appreciation of an apprehended moment is a judgment of both value and fact:

Appreciative behavior involves making judgments of value no less than judgments of reality. . . . Interests and standards . . . are systematically organized, a value system, distinguishable from the reality system yet inseparable from it. For facts are relevant only by reference to some judgment of value and judgments of value are meaningful only in regard to some configuration of fact. Hence the need for a word to embrace the two, for which I propose the word appreciation, a word not yet appropriated by science which in its ordinary use (as in “appreciation of a situation”) implies a combined judgment of value and fact. [Vickers, 1968, pp. 164–198]

Appreciation of apprehended reality is the source of values. Most mature value judgments are combinations of value and fact. Yet it is the affective core of values that fuel them, giving values the power to select and direct behavior.

Finally, appreciation is a process of affirmation. Unlike criticism, which is based on skepticism and doubt (compare Polanyi, 1958, pp. 269ff.), appreciation is based on belief, trust, and conviction. To appreciate apprehended reality is to embrace it. And from this affirmative embrace flows a deeper fullness and richness of experience. This act of affirmation forms the foundation from which critical comprehension can develop. In Polanyi’s words:

We must now recognize belief once more as the source of all knowledge. Tacit assent and intellectual passions, the sharing of an idiom and of a cultural heritage, affiliation to a like-minded community; such are the impulses which shape our vision of the nature of things on which we rely for our mastery of things. No intelligence, however critical or original, can operate outside such a fiduciary framework. [Polanyi, 1958, p. 266]

Appreciative apprehension and critical comprehension are thus fundamentally different processes of knowing. Appreciation of immediate experience is an act of attention, valuing, and affirmation, whereas critical comprehension of symbols is based on objectivity (which involves a priori control of attention, as in double-blind controlled experiments), dispassionate analysis, and skepticism. As we will see, knowledge and truth result not from the preeminence of one of these knowing modes over the other but from the intense coequal confrontation of both modes.

A third difference between knowing by apprehension and by comprehension is perhaps the most critical for our understanding of the nature of knowledge in its relationship to learning from experience. Apprehension of experience is a personal subjective process that cannot be known by others except by the communication to them of the comprehensions that we use to describe our immediate experience. Comprehension, on the other hand, is an objective social process, a tool of culture, as Engels would call it. From this it follows that there are two kinds of knowledge: personal knowledge, the combination of my direct apprehensions of experience and the socially acquired comprehensions I use to explain this experience and guide my actions; and social knowledge, the independent, socially, and culturally transmitted network of words, symbols, and images that is based solely on comprehension. The latter, as Dewey noted, is the civilized objective accumulation of the individual person’s subjective life experience.

It is commonly assumed that what we are calling social knowledge stands alone from the personal experience of the user. When we think of knowledge, we think of books, computer programs, diagrams, and the like, organized into a coherent system or library. Social knowledge, however, cannot exist independently of the knower but must be continuously recreated in the knower’s personal experience, whether that experience be through concrete interaction with the physical and social world or through the media of symbols and language. With symbols and words in particular, we are often led into the illusion that knowledge exists independently in the written work or mathematical notation. But to understand these words and symbols requires a knower who understands and employs a transformational process in order to yield personal knowledge and meaning. If, for example, I read that a “black hole” in astronomy is like a gigantic spiral of water draining from a bathtub, I can create for myself some knowledge of what a black hole is like (such as the force of gravity drawing things into it) based on my concrete experiences in the bath. This, however, is quite a different knowledge of black holes from that of the scientists who understand the special theory of relativity, the idea that gravity curves space, and so on. Personal knowledge is thus the result of the transaction between the form or structure of its external representational and transformational grammar (social knowledge, such as the bathtub image or the formal theory of relativity) and the internal representational and transformation processes that the person has developed in his or her personal knowledge system.

The Dialectics of Apprehension and Comprehension

Thoughts without content are empty Intuitions without concepts are blind.

—Immanuel Kant

The dynamic relation between apprehension and comprehension lies at the core of knowledge creation. The mind, to use Sir Charles Sharrington’s famous phrase, is “an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern, always a meaningful pattern though never an abiding one. . . .” Normal human consciousness is a combination of two modes of grasping experiences, forming a continuous experiential fabric, the warp of which represents apprehended experiences woven tightly by the weft of comprehended representations. Just as the patterns in a fabric are governed by the interrelations among warp and weft, so too, personal knowledge is shaped by the interrelations between apprehension and comprehension. The essence of the interrelationship is expressed in Kant’s analysis of their interdependence: Apprehensions are the source of validation for comprehensions (“thoughts without content are empty”), and comprehensions are the source of guidance in the selection of apprehensions (“intuitions without concepts are blind”).

Immediate apprehended experience is the ultimate source of the validity of comprehensions in both fact and value. The factual basis of a comprehension is ultimately judged in terms of its connection with sense experience. Its value is similarly judged ultimately by its immediate affective utility. Albert Einstein describes the relation between apprehension and comprehension thus:

For me it is not dubious that our thinking goes on for the most part without use of signs (words) and beyond that to a considerable degree unconsciously. For how otherwise should it happen that sometimes we “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” seems to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts which is already sufficiently fixed in us. Whenever such a conflict is experienced hard and intensively, it reacts back upon our thought world in a decisive way. The development of this thought world is in a certain sense a continuous flight from “wonder.” . . .

I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions which are laid down in books. The relations between the concepts and propositions among themselves and each other are of a logical nature, and the business of logical thinking is strictly limited to the achievement of the connection between concepts and propositions among each other according to firmly laid down rules which are the concern of logic. The concepts and propositions get “meaning,” viz. “content,” only through their connection with sense-experiences. The connection of the latter with the former is purely intuitive, not itself of a logical nature. The degree of certainty with which this relation, viz. intuitive connection, can be undertaken, and nothing else differentiates empty phantasy from scientific “truth.” [Schilpp, 1949]

More directly, the physicist David Bohm says, “All knowledge is a structure of abstractions, the ultimate test of the validity of which is, however, in the process of coming into contact with the world that takes place in immediate perception” (1965, p. 220).

Comprehensions, on the other hand, guide our choices of experiences and direct our attention to those aspects of apprehended experience to be considered relevant. Comprehension is more than a secondary process of representing selected aspects of apprehended reality. The process of critical comprehension is capable of selecting and reshaping apprehended experience in ways that are more powerful and profound. The power of comprehension has led to the discovery of ever-new ways of seeing the world, the very connection between mind and physical reality that Piaget noted earlier (compare Dewey, 1958, pp. 67–68). Dewey describes the powers of comprehension over the immediacy of apprehension in his reference to William James:

Genuine science is impossible as long as the object esteemed for its own intrinsic qualities is taken as the object of knowledge. Its completeness, its immanent meaning, defeats its use as indicating and implying.

Said William James, “Many were the ideal prototypes of rational order: teleological and esthetic ties between things . . . as well as logical and mathematical relations. The most promising of these things at first were of course the richer ones, the more sentimental ones. The baldest and least promising were mathematical ones; but the history of the latter’s application is a history of steadily advancing successes, while that of the sentimentally richer ones is one of relative sterility and failure. Take those aspects of phenomena which interest you as a human being most . . . and barren are all your results. Call the things of nature as much as you like by sentimental moral and esthetic names, no natural consequences follow from the naming. . . . But when you give the things mathematical and mechanical names and call them so many solids in just such positions, describing just such paths with just such velocities, all is changed. . . . Your “things” realize the consequences of the names by which you classed them.”

A fair interpretation of these pregnant sentences is that as long as objects are viewed telically, as long as the objects of the truest knowledge, the most real forms of being, are thought of as ends, science does not advance. Objects are possessed and appreciated, but they are not known. To know means that men have become willing to turn away from precious possessions; willing to let drop what they own, however precious, in behalf of a grasp of objects which they do not as yet own. Multiplied and secure ends depend upon letting go existent ends, reducing them to indicative and implying means. [John Dewey quoting William James, 1958, pp. 130–131]

Dialectics, Doubt, and Certainty

The relationship between apprehension and comprehension is dialectic in the Hegelian sense that although the results of either process cannot be entirely explained in terms of the other, these opposite processes merge toward a higher truth that encompasses and transcends them. The process whereby this synthesis is achieved, however, is somewhat mysterious; that is, it cannot be explained by logical comprehension alone. Thus the development of knowledge, our sense of progress in the refinement of ideas about ourselves and the world around us, proceeds by a dynamic that in prospect is filled with surprising, unanticipated experiences and insights, and in retrospect makes our earlier earnest convictions about the nature of reality seem simplistic and dogmatic. As learners, engaged in this process of knowledge creation, we are alternatively enticed into a dogmatic embrace of our current convictions and threatened with utter skepticism as what we thought were adamantine crystals of truth dissolve like fine sand between our grasping fingers. The posture of partial skepticism, of what Perry (1970) calls commitment within relativism, that is needed to openly confront the conflict inherent in the dialectic process is difficult to maintain. The greatest challenge to the development of knowledge is the comfort of dogmatism—the security provided by unquestioned confidence in a statement of truth, or in a method for achieving truth—or even the shadow dogmatism of utter skepticism (for to be utterly skeptical is to dogmatically affirm that nothing can be known).

Our primitive ancestors leaned toward a dogmatic affirmation of apprehension and a tenacious reliance on immediate sensation and feelings, a concrete approach to knowledge that was manifest in the formulation of animistic world views and a “science of the concrete” (Levi-Strauss, 1969). In Plato’s Phaedrus, the ancients’ mistrust of comprehension is nicely portrayed in the mythical conversation between the Egyptian god Thoth, who invented writing, and Thamus, a god-king who chastises Thoth for his invention:

This discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence; and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without its reality. [From Sagan, 1977, pp. 222–223]

The modern tendency, however, is to embrace the comprehension pole of the knowledge dialectic and to view with suspicion the intuitions of subjective experience. The clearest and most extreme intellectual expressions of modern reliance on comprehension are manifest in the domination of American psychology by behaviorist theories and methodologies and in the epistemological philosophy that spawned behaviorism—logical positivism. In a zeal born out of the upending of the tidy system of classical physics before the discoveries of modern twentieth-century physics, positivism sought to affirm that all knowledge must ultimately be based on empirical or logical data. In this way, the most dogmatic of the positivists denied the existence of subjective experiences (apprehensions) except insofar as these were verifiable by a community of observers following logical and scientific conventions (comprehensions).

In response to the positivists’ dogmatic embrace of comprehension, Polanyi proposes an equally dogmatic embrace of apprehension to confront the modern supremacy of analytic powers:

As I surveyed the operations of the tacit coefficient in the act of knowing, I pointed out how everywhere the mind follows its own self-set standards, and I gave my tacit or explicit endorsement to this manner of establishing truth. Such an endorsement is an action of the same kind as that which it accredits and is to be classed therefore as a consciously a-critical statement.

This invitation to dogmatism may appear shocking; yet it is but the corollary to the greatly increased critical powers of man. These have enhanced our mind with a capacity for self-transcendence of which we can never divest ourselves. We have plucked from the Tree a second apple which has forever emperiled our knowledge of Good and Evil, and we must learn to know these qualities henceforth in the blinding light of our new analytical powers. Humanity has been deprived a second time of its innocence, and driven out of another garden which was, at any rate, a Fool’s Paradise. Innocently, we had trusted that we could be relieved of all personal responsibility for our beliefs by objective criteria of validity—and our own critical powers have shattered this hope. Struck by our sudden nakedness, we may try to brazen it out by flaunting it in a profession of nihilism. But modern man’s immorality is unstable. Presently his moral passions reassert themselves in objectivist disguise and the scientistic Minotaur is born. [Polanyi, 1958, p. 268]

We are thus led to the conclusion that the proper attitude for the creation of knowledge is neither a dogmatism of apprehension or comprehension nor an utter skepticism, but an attitude of partial skepticism in which the knowledge of comprehension is held provisionally to be tested against apprehensions, and vice versa. The critical difference between personal and social knowledge is the presence of apprehension as a way of knowing in personal knowledge. It should be clear that the apprehensional portion of personal knowledge is all that prevents us from losing our identity as unique human beings, to be swallowed up in the command feedback loops of the increasingly computerized social-knowledge system. Because we can still learn from our own experience, because we can subject the abstract symbols of the social-knowledge system to the rigors of our own inquiry about these symbols and our personal experience with them, we are free. This process of choosing to believe is what we feel when we know that we are free to chart the course of our own destiny.

The Structure of Social Knowledge: World Hypotheses

Since all social knowledge is learned, it is reasonable to suspect that there is some isomorphism between the structure of social knowledge and the structure of the learning process. Thus it seems likely that some systems of knowledge will rely heavily on comprehension and others will rely on apprehension; some will be oriented to extension and practical application and others will be oriented toward intention and basic understanding. The philosopher Stephen Pepper, in his seminal work, World Hypotheses, proposes just such a framework for describing the structure of knowledge based on the fundamental metaphysical assumptions or “root metaphors” of systems for developing refined knowledge from common sense:

This tension between common sense and expert knowledge, between cognitive security without responsibility and cognitive responsibility without full security, is the interior dynamics of the knowledge situation. The indefiniteness of much detail in common sense, its contradictions, its lack of established grounds, drive thought to seek definiteness, consistency, and reasons. Thought finds these in the criticized and refined knowledge of mathematics, science, and philosophy, only to discover that these tend to thin out into arbitrary definitions, pointer readings, and tentative hypotheses. Astounded at the thinness and hollowness of these culminating achievements of conscientiously responsible cognition, thought seeks matter for its definitions, significance for its pointer readings, and support for its wobbling hypotheses. Responsible cognition finds itself insecure as a result of the very earnestness of its virtues. But where shall it turn? It does, in fact, turn back to common sense, that indefinite and irresponsible source which it so lately scorned. But it does so, generally, with a bad grace. After filling its empty definitions and pointer readings and hypotheses with meaning out of the rich confusion of common sense, it generally turns its head away, shuts its eyes to what it has been doing, and affirms dogmatically the self-evidence and certainty of the common-sense significance it has drawn into its concepts. Then it pretends to be securely based on self-evident principles or indubitable facts. If our recent criticism of dogmatism is correct, however, this security in self-evidence and indubitability has proved questionable. And critical knowledge hangs over a vacuum unless it acknowledges openly the actual, though strange, source of its significance and security in the uncriticized material of common sense. Thus the circle is completed. Common sense continually demands the responsible criticism of refined knowledge, and refined knowledge sooner or later requires the security of common-sense support. [Pepper, 1942, pp. 44–46]*

* Reprinted from World Hypotheses by Stephen C. Pepper by permission of the University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Root metaphors are drawn from experiences of common sense and are used by philosophers to interpret the world. Each of the major philosophies has cognitively refined one of these root metaphors into a set of categories that hang together and claim validity by all evidence of every kind. From the seven or eight such clues or root metaphors in the epistemological literature, Pepper argues that there are only four that are relatively adequate in precision (how accurately they fit the facts) and scope (the extent to which all known facts are covered) and can thus claim the status of a world hypothesis.

The first of these, Pepper calls formism (also known as realism), whose root metaphor is the observed similarity between objects and events. The second is mechanism (also called naturalism or materialism), whose root metaphor is the machine. The third is contextualism (better known as pragmatism), with the root metaphor of the changing historical event. The final relatively adequate world hypothesis is organicism (absolute idealism), whose root metaphor is achievement of harmonious unity. None of these world hypotheses is reflected in pure form in the work of any single philosopher, since most philosophers tend to be somewhat eclectic in their use of world hypotheses. For purposes of understanding, however, we can say that formism originated in the classical works of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and mechanism in the works of Democritus, Lucretius, and Galileo. Contextualism is more modern, originating in the works of Dewey, James, Peirce, and Mead, as is organicism, developed primarily in the work of Hegel and Royce.

The isormorphism between Pepper’s system of world hypotheses and the structure of the learning process becomes apparent in his analysis of the interrelationships among the four world hypotheses. Formism and mechanism, the two world hypotheses underlying modern science, are primarily analytic in nature, wherein elements and factors are the basic facts from which any synthesis is a derivative. Contextualism and organicism, on the other hand, are synthetic, wherein the basic facts are contexts and complexes such that analysis of components is a derivative of the synthetic whole. Within both the analytic and synthetic world hypotheses there is a further polarity between dispersive and integrative strategies of inquiry. Formism and contextualism are both dispersive in their plan, explaining facts one by one without systematic relationship to one another. Indeed, both formism and contextualism see the world as indeterminate and unpredictable. Organicism and mechanism are integrative in their plan, believing in an integrated world order where indeterminance is simply a reflection of inadequate knowledge. Because they seek integrative determinant explanations, the strength of the integrative world hypotheses (organicism and mechanism) is precision and predictability; their weakness is lack of scope, their inability to achieve an integrated explanation of all things. The dispersive world hypotheses, on the other hand, are weak in precision, offering several possible interpretations for many events, but strong in scope, since their explanatory range is not restricted by any integrative principle.

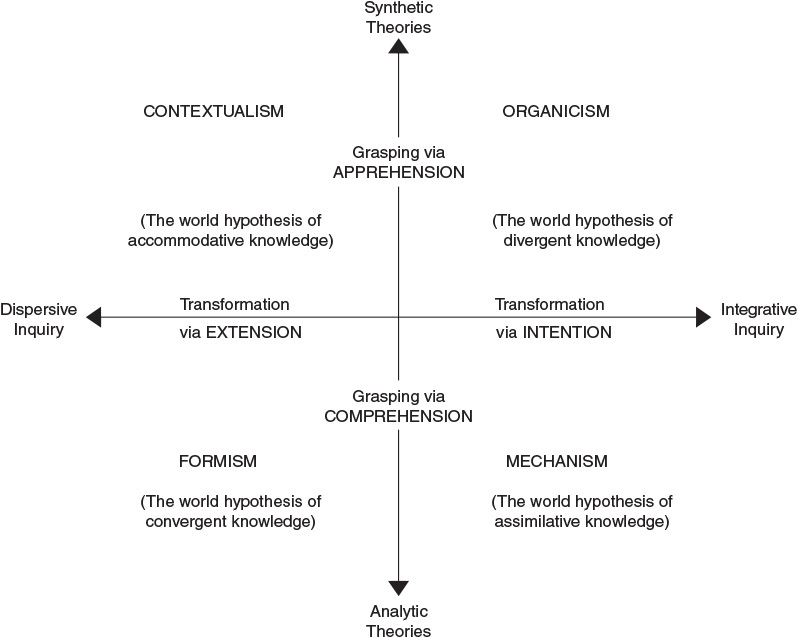

Figure 5.1 shows Pepper’s system of world hypotheses overlaid on the structural dimensions of the learning process. The analytic world views emphasize knowing by comprehension, and the synthetic world views give primary emphasis to knowing by apprehension. The dispersive philosophies emphasize transformation by extension, the discovery and explanation of laws and events in the external world; the integrative philosophies emphasize transformation by intention, the search for underlying principles and integrated meaning.

Formism and Mechanism—The Analytic World Hypotheses Based on Comprehension

Inquiry in modern science rests primarily on the metaphysical foundations of formism and mechanism. The modern version of formism, realism, incorporates many of the characteristics of mechanism, such as an emphasis on space/time location, so that the two root metaphors are often indistinguishable. E. A. Burtt describes this interrelationship between the two analytic world hypotheses by illustrating how both are central to the concept of law:

In its very essence this concept [law] preserves something vital in the formistic conception of “form” as well as something vital in the mechanistic conception of “regular interrelationship” among the parts of a machine. And I can think of no statement of either formism or mechanism as a metaphysical view, calculated to appear at all persuasive to any modern mind, which has not somewhere drawn upon those features of modern science which synthesize earlier formism and mechanism in precisely this fashion. [Burtt, 1943, p. 600]

There is, however, an important sense in which the two analytic world hypotheses support different modes of inquiry based on the dispersive nature of formism and the integrative nature of mechanism. Mechanism as an integrative strategy is better suited as a foundation for basic research in the physical sciences and mathematics, whereas formism’s dispersive plan is more attuned to inquiry in the applied sciences and the science-based professions, where the dictates of practical circumstance often take precedence over the achievement of integrative frameworks. Even though the dispersive nature of formism creates constant difficulties of precision because of the many interpretations to which a single fact is amenable, from a practical standpoint this variety offers flexibility in problem solving.

Formism’s root metaphor of similarity is based on the commonsense perception of similar things. It is reliance on this root metaphor that allows the creation of systems of classifications based on similarity, such as the periodic table of elements or biological phyla. It is also the basis by which the validity of models, maps, and mathematical relationships is judged—that is, by similarity of these symbolic comprehensions to the reality being studied. Thus, the formist theory of truth is correspondence; the truth of a description lies in its degree of correspondence to the object of reference.

The modern formist inquiry strategy, sometimes called scientific empiricism, places great emphasis on the judgments of concrete existence through reports of sense experience controlled by the conventions of logic and scientific method. In this sense, even logical positivism, which adamantly denies any metaphysical foundation, is based on formism, since similar judgments by scientists of their sense experience are the basis for confidence in positivistic statements. Knowledge in modern formist inquiry is created when the community of scientists is able to agree on the reliable and accurate location of phenomena in time and space—to answer the inquiry questions, “When?” and “Where?” Singer (1959) traces the Platonic origins of such space/time individuation and compares this empirical approach to the rationalist Leibnitzian approach:

As for the tradition, it goes back at least as far as to Plato, who in his Timaeus makes space the “pure matter” that individuates general qualities (i.e., takes care of the distinction between this thing and that other precisely like thing). And from Plato’s time down, it would be possible to trace an imposing history of spacetime individuation. As for practical sanctions, our courts of justice recognize the all-important difference between the evidence established by “identification by minute description” and the evidence established by “individuation by space-time coordinates.” The former, Leibnitzian, method of identification is exactly the one underlying our present method of “police identification.” With sufficient refinement of detail, Bertillon measurements may be made to constitute an indefinitely minute description of the kind of man a certain individual is. But suppose the accused “identified” with the culprit to the limit of available description; how long would he remain in the dock could he establish an “alibi”? In insisting that the same individual cannot be in two places at the same time, in admitting that two individuals, however like, can be, the law throws the whole weight of its authority on the side of Kant and against Leibnitz. [Singer, 1959, p. 43]

The basic units of knowledge in formism are empirical uniformities and natural laws. The emphasis is on the analysis, measurement, and categorization of observable experience and the establishment of empirical uniformities defining relationships between observed categories—that is, natural laws—with a minimum of reliance on inferred structures or processes that are not directly accessible to public experience.

Mechanism as a world hypothesis is less trusting of the appearances of sense experience and relies more on rationalist principles to analytically separate appearances from reality. The root metaphor of mechanism is the machine, and knowledge in mechanism is refined by analyzing the world as if it were a machine. Central to this analysis is the distinction between primary and secondary qualities. Primary qualities are those features and characteristics that are essential to describing the functioning of the machine. The traditional primary qualities have been size, shape, motion, solidity, mass, and number. In the case of a lever, for example, the primary qualities would be the length of the lever, the location of the fulcrum, and the weights applied at either end. Secondary qualities would be all other characteristics of the lever, such as its color and the material the weights are made of, that are not essential to explaining its functioning. As Democritus, one of the classical founders of mechanism, put it, “By convention colored, by convention sweet, by convention bitter; in reality only atoms and the void.” There are six steps or categories in mechanistic analysis:

1. Specification of the field of location in time and space. (In mechanism, everything that exists exists somewhere, unlike classical formism, where form exists independently of particulars in time and space.)

2. Identification of primary qualities.

3. Description of laws governing primary qualities.

4. Description of secondary qualities.

5. Principles for connecting secondary qualities and primary qualities.

6. Laws for regularities among secondary qualities.

The theory of truth in mechanism is somewhat problematic, since, as Pepper points out, primary qualities can be known only by inference from secondary qualities; in other words, they are comprehensions:

. . . all immediate evidence seems to be of the nature of secondary qualities (all ultimate primary qualities such as the properties of electrons and the cosmic field being far from the range of immediate perceptions); moreover, this evidence seems to be correlated with the activities of organisms, specifically with each individual organism that is said to be immediately aware of evidence. All immediate evidence is, therefore, private to each individual organism. It follows that knowledge of the external world must be symbolic and inferential. . . . So that in a mature mechanism, the primary qualities and all the primary categories are not evidence but inference, or if you will, speculation. [Pepper, 1942, pp. 221 and 224]

The proper theory of truth for mechanism thus lies in the correlation of primary qualities with secondary qualities in what Pepper calls the causal adjustment theory of truth: Does knowledge of the machine in question allow the person to make causal adjustments with predictable consequences for secondary qualities?

The basic units of knowledge in mechanism are the primary qualities or structures that make up the world. Structuralism is thus a modern variant of mechanism. Model building is a typical inquiry method of mechanism that seeks to answer the basic inquiry question, “What is real? What are the basic structures of reality?”—as, for example, in the discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule.

We must stand in awe of the achievements of modern science and thereby give great credibility to the scientific inquiry methods based on formism and mechanism. These represent the highest refinement of human powers of comprehension. Yet ironically, the greatest achievement of scientific inquiry may be the discovery of its own limitations. The history of science is marked by the successive overthrow of widely accepted views of the nature of reality in favor of new, more all-encompassing but more question-provoking views. Today there is little dogma in enlightened scientific inquiry, for the assumptions on which scientific systems of comprehension are based have been challenged by scientific discoveries at the forefront of knowledge. The invention and later validation of non-Euclidian geometry in Einstein’s theory of space and time brought down the principles of nineteenth-century science and the “self-evident” Kantian a priori forms on which they were based. A number of subsequent discoveries brought into question the very notion of permanent external objects independent of the observer. Whether light is a wave or particle depends on how it is measured. The so-called “bootstrap” theory of the nucleus suggests that subatomic particles inside the nucleus of the atom have no self-sufficient existence, since their properties are determined by their neighbors, and vice versa. Thus, particles in the nucleus gain existence only when they are knocked out of the nucleus by a scientist. The well-known Heisenberg principle of indeterminacy showed that one cannot measure both the location and the momentum of a particle with certainty. In Heisenberg’s words, “What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our methods of questioning.”

There are corresponding limitations and indeterminacies in formal systems of logic. In 1931, Kurt Gödel showed that no consistent formal system sufficiently rich to contain elementary arithmetic can by its own principles of reasoning demonstrate its own consistency, a theorem that defined the limits of comprehension as a way of knowing. From Gödel’s theorem we are led to the conclusion that to judge the logical consistency of any complex formal system, we must go outside it. Commenting on this indeterminate characteristic of formal systems, a characteristic that he calls tacit meaning, Polanyi says:

Thus to speak a language is to commit ourselves to the double indeterminacy due to our reliance both on its formalism and on our own continued reconsideration of this formalism in its bearing on our experience. For just as, owing to the ultimately tacit character of all our knowledge, we remain ever unable to say all that we know, so also in view of the tacit character of meaning, we can never quite know what is implied in what we say. [Polanyi, 1958, p. 95]

Contextualism and Organicism—The Synthetic World Hypotheses Based on Apprehension

The recently recognized limitations of comprehension-based knowledge structures have undoubtedly given sustenance to the development of the synthetic world hypotheses based on apprehension. John Dewey, in Experience and Nature, argued that the earlier dogmatic intellectualism of science created an unnatural separation of primary experience from nature in which nature became indifferent and dead and human beings were alienated from their own subjective experience, their hopes and dreams, fears and sorrows:

The assumption of intellectualism goes contrary to the facts of what is primarily experienced. For things are objects to be treated, used, acted upon and with, enjoyed and endured, even more than things to be known. They are things had before they are things cognized. . . . When intellectual experience and its material are taken to be primary, the cord that binds experience and nature is cut. [Dewey, 1958, pp. 21 and 23]

The systems of social knowledge based on the synthetic world hypotheses operate under something of a handicap, since they must express understandings stemming from apprehension in the social language of comprehension. When the linear, digital descriptions of language and mathematics are used to describe the holistic, analogic context of apprehended experience, the result often seems exceedingly complex and abstract. Yet organicism and contextualism have proven themselves strong in the field of human values and practical affairs—areas where the analytic world theories are weak. Pepper states, for example:

It may be pointed out that the mechanistic root metaphor springs out of the commonsense field of uncriticized physical fact, so that there would be no analogical stretch, so to speak, in the mechanistic interpretations of this field, while the stretch might be considerable in the mechanistic interpretation of the commonsense field of value; and somewhat the same, in the reverse order, with respect to organistic interpretations. Moreover, mechanism has for several generations been particularly congenial to scientists and organicism to artists and to persons of religious bent. Also, the internal difficulties which appear from a critical study of the mechanistic theory seem to be particularly acute in the neighborhood of values, and counterwise the internal difficulties of organicism seem to be particularly acute in the neighborhood of physical fact. [Pepper, 1942, p. 110]

Like mechanism and formism, the synthetic world theories contextualism and organicism tend to combine and:

. . . are so nearly allied that they may almost be called the same theory, the one with a dispersive, the other with an integrative plan. Pragmatism has often been called an absolute idealism without an absolute; and, as a first approximate description, this is acceptable. So a little more emphasis on integration, as Dewey for instance shows in his Art as Experience, produces a contextualistic-organistic eclecticism; as likewise a little less emphasis on final integration in organicism, as is characteristic of Royce. Royce even called himself somewhere a pragmatic idealist. [Pepper, 1942, p. 147]

The contextualist approach, however, has a certain affinity to the world of practical affairs in business, politics, and the social professions, whereas the organistic approach, with its emphasis on absolute values and ideals, is more attuned to the humanities, arts, and social sciences.

The root metaphor of organicism is what Burtt calls harmonious unity. The metaphor stems from the biological organism growing to its fulfillment. The central concern of organismic worldviews is growth and development, with a focus on the processes whereby the ideal is realized from the actual. These processes are most often conceived as some process of differentiation and higher-order integration. This process is teleological toward the absolute, not evolutionary as in the biological principles of natural selection, which are closer to contextualism’s open-ended developmental processes. The organismic view of development is the basis of modern humanistic developmental psychology—most notably, Abraham Maslow’s theory of self-actualization—and in somewhat more dispersive, contextual, evolutionary forms, organicism is the basis for research in cognitive and adult development. Much historical analysis is loosely based on the organistic world hypothesis, although Hegel’s teleological progression to the Absolute is widely questioned. To modern organicists, Hegel’s view of development was a dogmatic and unnecessarily narrow progression from maximum fragmentation to his ultimate integration via the dialectic process:

Hegel was right, say these later organicists, in the inevitability of the trend of cognition toward a final organization in which all contradictions vanish. He was right in his observation that the nexes of fragments lead out toward other fragments which develop contradictions and demand coherent resolution. He was right in his idea that these nexes have a particular attraction for those relevant traits which are peculiarly recalcitrant to harmonization with the facts already gathered. It was the aberrations in the orbit of Uranus, those recalcitrant data which refused to harmonize with the Newtonian laws, that particularly attracted the attention of astronomers and led to the discovery of Neptune. In all these things Hegel was right. But he was wrong and invited undeserved ridicule for the organistic program by his fantastic, arbitrary, and rigid picture of the path of progress. [Pepper, 1942, pp. 294–295]

The theory of truth in organicism is coherence and is derived from the endpoint of development, the Absolute—an organic whole that includes everything in a totally determinant order. Thus, the truth of a proposition is the degree to which it is inclusive, determinant, and organized in an organic whole where every element relates to every other in an interdependent system. There is a certain similarity in this description of organismic truth to the primary quality structures of mechanism, but in mechanism, the emphasis is on structures, whereas in organicism, it is on the processes by which progress is made to the determinant orderliness of the whole.

The basic inquiry question of organicism is one of ultimate values—why things are as they are. Whereas mechanism relies on symbols and the denotative functions of language, there is a tendency in organicism to rely on images and the connotative aspects of language to describe the apprehensions (appearances) from which reality emerges. DeWitt identifies five characteristics of organic concepts: They are holistic, visually apprehended, organized aesthetically and neatly, and functionally based:

In sum [these characteristics] emphasize the relation of organic concepts to ordinary experience; that is, experience in a universe where straight parallel lines meet at infinity, where the sun visibly rises and sets, where the earth is flat (at least its curvature is of no practical importance), where cause and effect have a direct sequential relationship, where action does not take place without an immediate objective as the motive of the action, where objects are visibly finite. This is the universe which accounts for almost all our everyday experiences but represents a very limited range of experience—involving, if you will, the statistical fallacy that frequency of occurrence is an index of importance. [DeWitt, 1957, p. 182]

The final world hypothesis is contextualism. Although Pepper treats each of the four systems evenhandedly in his 1942 book, later, in Concept and Quality (1966), he embraces a modified version of contextualism (he calls his new world hypothesis “selectivism”) as the most adequate of the existing world hypotheses. The advantage of contextualism (selectivism) over the other three world hypotheses is that it integrates fact and value in an open-minded and open-eyed way—a way that is emergent and slightly optimistic, with no dogma of method or tool save a commitment to humanity. The root metaphor of contextualism is the historical event—not the past historical event, but the immediate event, alive in the present—actions in their context evolving and creating the future. Contextualism as a synthetic world hypothesis is concerned with the concrete event as experienced in all its complexity. The one constant in contextualism is change. Reality is constantly being created and re-created. Thus, the permanent forms of formism or structures of mechanism cannot exist in the contextualist worldview. Whitehead (1933, p. 255) puts it this way: “Thus the future of the universe, though conditioned by the immanence of its past, awaits for its complete determination the spontaneity of the novel individual occasions as in their season they come into being.”

Inquiry in contextualism is focused on the quality and texture of the immediate event as experienced; hence its association with phenomenology. Lewin’s (1951) conception of the person’s life space as a field of forces in which behavior is determined by ahistorical causation (only forces existing in the moment, such as a memory, determine behavior) is a primary example of contextually based theory. In this theory of truth, the contextualist works from the present event outward in what is called the operational theory of truth. The basic inquiry question is how to act or think. Actions are true if they are workable; that is, if they lead to desired end states in experience. Hypotheses are true when they give insight into—are verified by—the quality and texture of the event to which they refer. Hypotheses thus achieve qualitative confirmation by the experiences to which they refer. In pure contextualism, however, the truth of a hypothesis gives no insight into the qualities of nature; for nature is constantly emerging and changing. A hypothesis is only a tool for controlling nature. “It does not mirror nature in the way supposed by the correspondence theory, nor is it a genuine partial integration of nature in the way supposed by the coherence theory of organicism” (Pepper, 1942, p. 275).

Summary

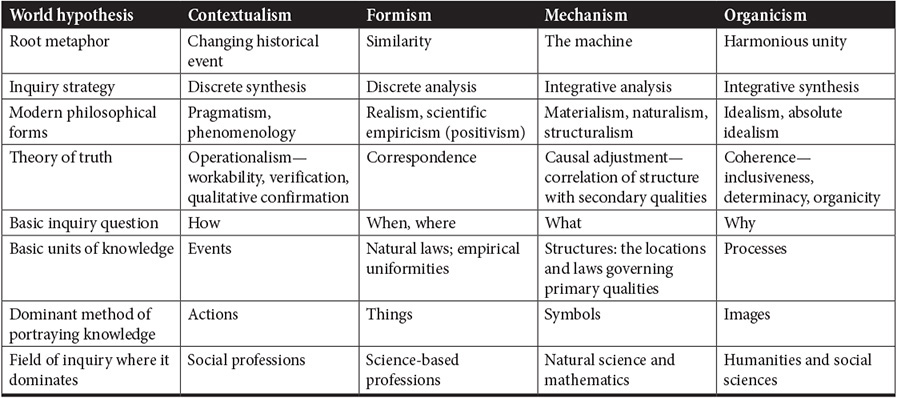

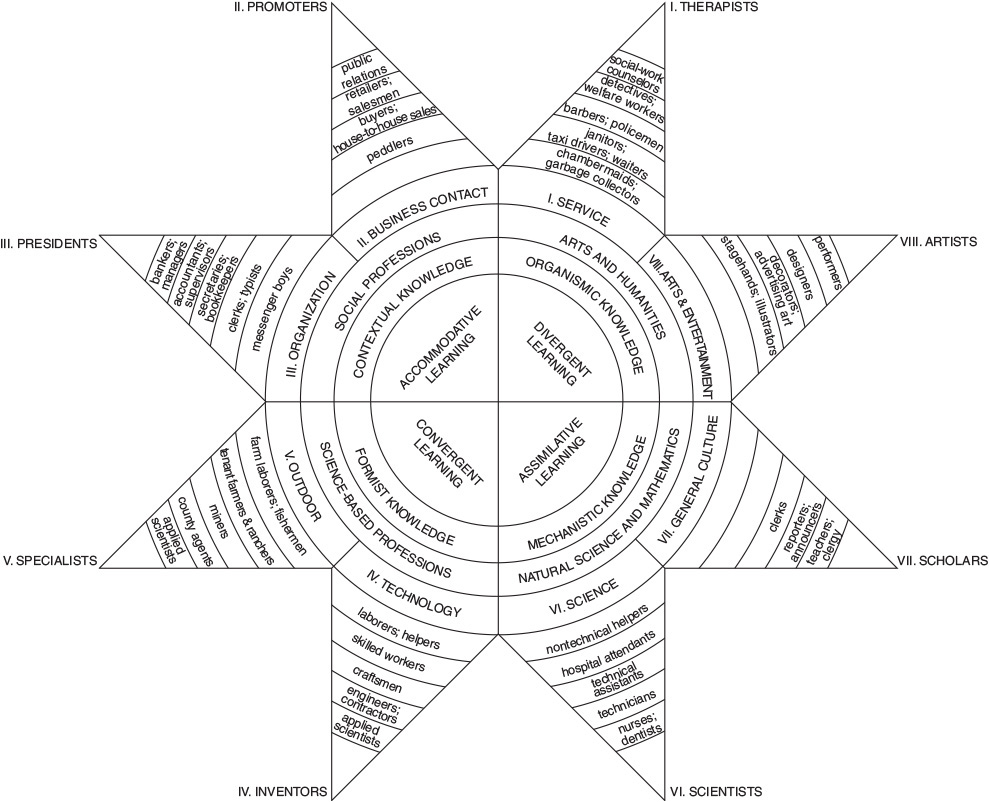

Table 5.1 summarizes the characteristics of the four world hypotheses—contextualism, organicism, formism, and mechanism—relating them to the fields of inquiry in which they seem to flourish best: respectively, the social professions, the humanities and social science, the science-based professions, and natural science and mathematics. The significance of Pepper’s metaphysical analysis lies in the identification of the basic inquiry structures for refining knowledge. These are derived from simple metaphors of common sense, which lay bare the root assumptions on which knowledge in each system is based. His typology introduces some order to the tangled, fast-growing thicket of social knowledge. The system is perhaps best treated in the framework of contextualism—as a set of hypotheses to be verified, as useful tools for examining knowledge structures in specific contexts. It is to just such an analysis that we now turn.

Table 5.1 A Typology of Knowledge Structures (World Hypotheses) and Their Respective Fields of Inquiry

Social Knowledge as Living Systems of Inquiry—The Relation between the Structure of Knowledge and Fields of Inquiry and Endeavor

Knowledge does not exist solely in books, mathematical formulas, or philosophical systems; it requires active learners to interact with, interpret, and elaborate these symbols. The complete structure of social knowledge must therefore include living systems of inquiry, learning subcultures sharing similar norms and values about how to create valid social knowledge. Academic disciplines, professions, and occupations are homogeneous cultures that differ on nearly every dimension associated with the term. There are different languages (or at least dialects). There are strong boundaries defining membership and corresponding initiation rites. There are different norms and values, particularly about the nature of truth and how it is to be sought. There are different patterns of power and authority and differing criteria for attaining status. There are differing standards of intimacy and modes for its expression. Cultural variation is expressed in style of dress (lab coats and uniforms, business suits, beards and blue jeans), furnishings (wooden or steel desks, interior decoration, functional rigor, or “creative disorder”), architecture, and use of space and time. Most important, these patterns of variation are not random but have a meaning and integrity for the members. There is in each discipline or profession a sense of historical continuity and, in most cases, historical mission.

If the central mission of the university is learning in the broadest sense, encompassing the student in the introductory lecture course and the advanced researcher in the laboratory, library, or studio, then it seems reasonable to hypothesize that different styles of learning, thinking, and knowledge creation are the focal points for cultural variation among disciplines. Different styles of learning manifest themselves in variations among the primary tasks, technologies, and products of disciplines—criteria for academic excellence and productivity, teaching methods, research methods, methods for recording and portraying knowledge—and in other patterns of cultural variation—differences in faculty and student demographics, personality and aptitudes, values and group norms. For example, Anthony Biglan (1973b) has found significant variations in departmental concerns and organization. In the soft areas (social professions and humanities/social science), there is less faculty interaction than in the hard areas (science-based professions and natural science/mathematics); and in the hard areas, this interaction is strongly associated with research productivity. Hard-area scholars produce fewer manuscripts but more journal articles. The emphasis in soft areas is on teaching, and in hard areas on research. Applied areas (social and science-based professions) show more faculty social connectedness than do basic areas (humanities/social science, natural science/mathematics). Their research goals are influenced more by others, including outside agencies, although they are less interested in research than are their basic area colleagues. They publish more technical reports than their basic area colleagues, whose interest in research is not reflected in the time they spend on it.

In reviewing other research on differences among academic disciplines, one is struck by the fact that relatively little comparative research has been done on academic disciplines and departments. The reason for this lies in the same difficulties that characterize all cross-cultural research—the problem of access and the problem of perspective. The relatively closed nature of academic subcultures makes access to data difficult, and it is equally difficult to choose an unbiased perspective for interpreting data. To analyze one system of inquiry according to the ground rules of another is to invite misunderstanding and conflict and further restrict access to data.

To study disciplines from the perspective of learning offers some promise for overcoming these difficulties, particularly if learning is defined not in the narrow psychological sense of modification of behavior but in the broader sense of acquisition of knowledge. The access problem is eased, because every discipline has a prime commitment to learning and inquiry and has developed a learning style that is at least moderately effective. Viewing the acquisition of knowledge in academic disciplines from the perspective of the learning process promises a dual reward—a more refined epistemology that defines the varieties of truth and their interrelationships, and a greater psychological understanding of how people acquire knowledge in its different forms. Twenty years ago, Carl Bereiter and Mervin Freedman envisioned these rewards:

There is every reason to suppose that studies applying tests of these sorts to students in different fields could rapidly get beyond the point of demonstrating the obvious. We should, for instance, be able to find out empirically whether the biological taxonomist has special aptitudes similar to his logical counterpart in the field of linguistics. And there are many comparisons whose outcomes it would be hard to foresee. In what fields do the various memory abilities flourish? Is adaptive flexibility more common in some fields than in others? Because, on the psychological end, these ability measures are tied to theories of the structure or functioning of higher mental processes, and because, on the philosophical end, the academic disciplines are tied to theories of logic and cognition, empirical data linking the two should be in little danger of remaining for long in the limbo where so many correlational data stay. [Bereiter and Freedman, 1962, pp. 567–568]

It is surprising that with the significant exception of Piaget’s pioneering work on genetic epistemology, few have sought to reap these rewards.

The research that has been done has instead focused primarily on what, from the perspective above, are the peripheral norms of academic disciplines rather than the pivotal norms governing learning and inquiry. Thus, studies have examined political/social attitudes and values (Bereiter and Freedman, 1962), personality patterns (Roe, 1956), aspirations and goals (Davis, 1965), sex distribution and other demographic variables (Feldman, 1974), and social interaction (Biglan, 1973b; Hall, 1969). The bias of these studies is no doubt a reflection of the fact that psychological research has until quite recently been predominantly concerned with the social/emotional aspects of human behavior and development. Concern with cognitive/intellectual factors has been neatly wrapped into concepts of general intelligence. Thus, most early studies of intellectual differences among disciplines were interested only in which discipline has the smarter students (for example, Wolfe, 1954; Terman and Oden, 1947).

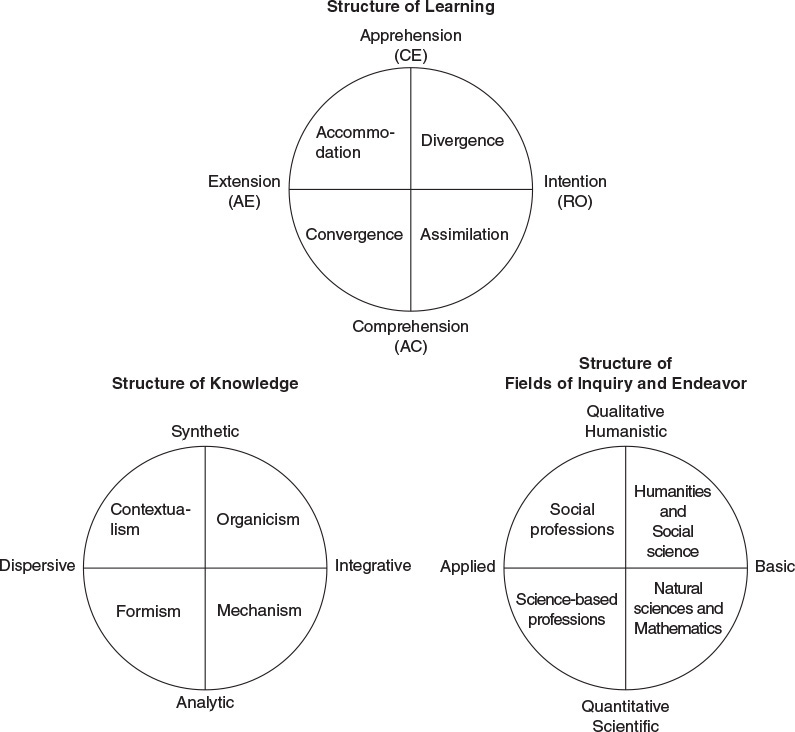

The hypothesis to be explored in this section is that since learning, broadly conceived as adaptation, is the central mission of every discipline and profession, the cultural variations among fields of inquiry and endeavor will be organized in a way that is congruent with the structure of the learning process and the structure of knowledge. When one examines academic disciplines in the four major groupings we have identified—the social professions, the science-based professions, humanities/social science, and natural science/mathematics—it becomes apparent that what constitutes valid knowledge in these four groupings differs widely. This is easily observed in differences in how knowledge is reported (for instance, numerical or logical symbols, words or images), in inquiry method (such as case studies, experiments, logical analysis), and in criteria for evaluation (say, practical vs. statistical significance). Figure 5.2 illustrates the specific relationship predicted among fields of inquiry, the structure of knowledge, and the structure of the learning process. We have in the preceding section elaborated on the relation between knowledge structures and the learning process and have seen in this analysis suggestions concerning the relation of knowledge and learning to living systems of inquiry. Synthetic knowledge structures learned via apprehension are associated with qualitative, humanistic fields, whereas analytic knowledge structures learned via comprehension are related to the quantitative scientific fields, dispersive knowledge structures learned via extension are related to the professions and applied sciences, and integrative knowledge structures learned via intention are related to the basic academic disciplines.

Figure 5.2 Relationships Among the Structure of the Learning Process, the Structure of Knowledge, and Fields of Inquiry and Endeavor

The Structure of Academic Fields

The first suggestion that experiential learning theory might provide a useful framework for describing variations in the inquiry norms of academic disciplines came in Chapter 4, when we examined the undergraduate majors of practicing managers and graduate students in management (see Figure 4.4). Although these people shared a common occupation, variations in their learning styles were strongly associated with their undergraduate educational experience. There was a good fit with the predictions outlined in Figure 5.2, showing a relation between the structure of learning as measured by individual learning style and one’s chosen field of specialization in college. Undergraduate business majors tended to have accommodative learning styles; engineers, on the average, fell in the convergent quadrant; history, English, political science, and psychology majors all had divergent learning styles; mathematics and chemistry majors had assimilative learning styles, as did economics and sociology majors; and physics majors were very abstract, falling between the convergent and assimilative quadrants. These data suggested that undergraduate education was a major factor in shaping individual learning style, either by the process of selection into a discipline or socialization while learning in that discipline, or, as is most likely the case, both.

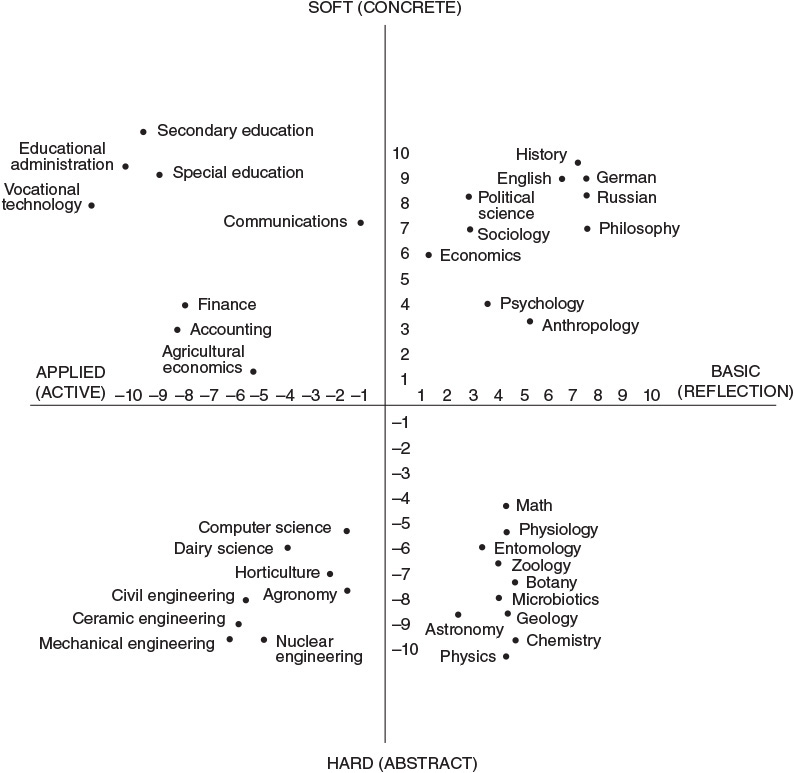

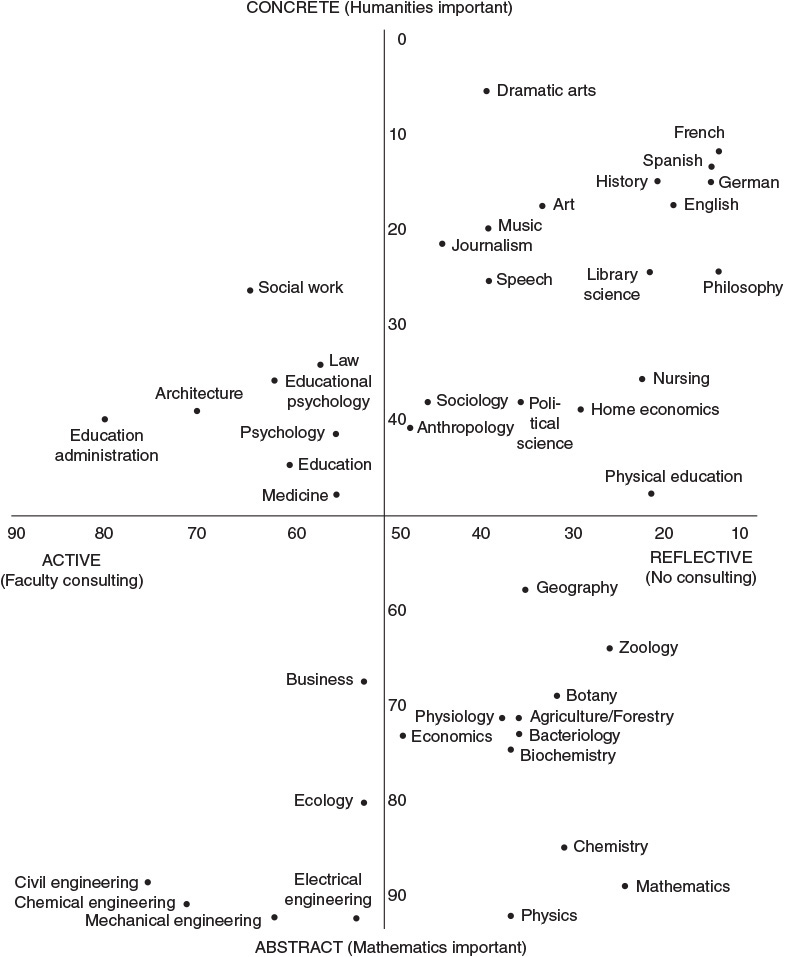

We now examine how others perceive the differences between academic disciplines and whether these perceptions are congruent with the structure of knowledge and learning. Anthony Biglan (1973a) used a method well suited to answer these questions in his studies of faculty members at the University of Illinois and a small western college. Using the technique of multidimensional scaling, he analyzed the underlying structures of scholars’ judgments about the similarities of subject matter in different academic disciplines. The procedure required faculty members to group subject areas on the basis of similarity without any labeling of the groupings. Through a kind of factor analysis, the similarity groupings are then mapped onto an n-dimensional space where n is determined by goodness of fit and interpretability of the dimensions. The two dimensions accounting for the most variance in the University of Illinois data were interpreted by Biglan to be hard-soft and pure-applied. When academic areas at Illinois are mapped on this two-dimensional space (Figure 5.3), we see a great similarity between the pattern of Biglan’s data and the structure of knowledge and learning described in Figure 5.2. Business (assumed equivalent to accounting and finance) is accommodative in learning style and contextualist in knowledge structure. Engineering fits with convergent learning and formist knowledge. Physics, mathematics, and chemistry are related to assimilative learning and mechanistic knowledge, and the humanistic fields—history, political science, English, and psychology—fall in the divergent, organistic quadrant. Foreign languages, economics, and sociology were divergent in Biglan’s study rather than assimilative as in Figure 4.4. Biglan also reported that the pattern of academic-area relationships in the small-college data was very similar to that in the Illinois data.

Source: Adapted from A. Biglan, “The Characteristics of Subject Matter in Different Academic Areas,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 57 (1973).

Figure 5.3 Similarities Among 36 Academic Specialties at the University of Illinois

These two studies suggest that the two basic dimensions of experiential learning theory, abstract/concrete and active/reflective, are major dimensions of differentiation among academic disciplines. A more extensive database is needed, however. The learning-style data came from a single occupation, and in the case of some academic areas, sample sizes were small. Biglan’s study, on the other hand, was limited to two universities, and differences here could be attributed to the specific characteristics of these academic departments.

In search of a more extensive and representative sample, data collected in the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education’s 1969 study of representative American colleges and universities were examined. These data consisted of 32,963 questionnaires from graduate students in 158 institutions and 60,028 questionnaires from faculty in 303 institutions. Using tabulations of these data reported in Feldman (1974), ad hoc indices were created of the abstract/concrete and active/reflective dimensions for the 45 academic fields identified in the study. The abstract/concrete index was based on graduate student responses to two questions asking how important an undergraduate background in mathematics or humanities was for their fields. The mathematics and humanities questions were highly negatively correlated (−.78). The index was computed using the percentage of graduate-student respondents who strongly agreed that either humanities or mathematics was very important:

Thus, high index scores indicated a field where a mathematics background was important and humanities was not important.

The active/reflective index used faculty data on the percentage of faculty in a given field who were engaged in paid consultation to business, government, and so on. This seemed to be the best indicator on the questionnaire of the active, applied orientation of the field. As Feldman observed, “Consulting may be looked upon not only as a source of added income but also as an indirect measure of the ‘power’ of a discipline; that is, as a chance to exert the influence and knowledge of a discipline outside the academic setting” (1974, p. 52). The groupings of academic fields based on these indices are shown in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 Concrete/Abstract and Active/Reflective Orientations of Academic Fields Derived from the Carnegie Commission Study of American Colleges and Universities

The indices produce a pattern of relationships among academic fields that is highly consistent with Biglan’s study and the managerial learning-style data. The results suggest that the widely shared view that cultural variation in academic fields is predominantly unidimensional, dividing the academic community into two camps—the scientific and the artistic (for example, Snow, 1963; Hudson, 1966)—is usefully enriched by the addition of a second dimension of action/reflection or applied/basic. When academic fields are mapped on this two-dimensional space, a fourfold typology of disciplines emerges. In the abstract/reflective quadrant, the natural sciences and mathematics are clustered; the abstract/active quadrant includes the science-based professions, most notably the engineering fields; the concrete/active quadrant encompasses what might be called the social professions, such as education, social work, and law; the concrete/reflective quadrant includes the humanities and social sciences.