6. The Experiential Learning Theory of Development

The course of nature is to divide what is united and to unite what is divided.

—Goethe

There is a quality of learning that cannot be ignored. It is assertive, forward-moving, and proactive. Learning is driven by curiosity about the here-and-now and anticipation of the future. It was John Dewey who saw that the experiential learning cycle was not a circle but a spiral, filling each episode of experience with the potential for movement, from blind impulse to a life of choice and purpose (see Chapter 2, “Dewey’s Model of Learning”). He compared this progression in learning from experience to the advance of an army:

Each resting place in experience is an undergoing in which is absorbed and taken home the consequences of prior doing, and unless the doing is that of utter caprice or sheer routine, each doing carries in itself meaning that has been extracted and conserved. As with the advance of an army, all gains from what has been already effected are periodically consolidated, and always with a view to what is to be done next. If we move too rapidly, we get away from the base of supplies—of accrued meanings—and the experience is flustered, thin, and confused. If we dawdle too long after having extracted a net value, experience perishes of inanition. [Dewey, 1934, p. 56]

Learning is thus the process whereby development occurs. This view of the relation between learning and development differs from some traditional conceptions that suggest that the two processes are relatively independent. This latter perspective, which is shared by the intelligence-testing movement and classical Piagetians, suggests that learning is a subordinate process not actively involved in development: To learn, one uses the achievements of development, but this learning does not modify the course of development. In intelligence testing, for example, development is seen as a prerequisite for learning—it is necessary for a child’s mental functions to mature before more complex subject matter can be taught. Similarly, for Piaget, development forms the superstructure within which learning occurs. His research has been guided by the implicit assumption that the sequence of cognitive-developmental stages evolves from an internal momentum and logic, with little influence from environmental circumstance. Recent research by those who might be called neo-Piagetians (such as Bruner et al., 1966) have called this assumption into question by showing in cross-culture studies that the child’s level of cognitive development at a given age is strongly influenced by access to Western-type schooling.

Learning and Development as Transactions between Person and Environment

Without denying the reality of biological maturation and developmental achievements (that is, enduring cognitive structures that organize thought and action), the experiential learning theory of development focuses on the transaction between internal characteristics and external circumstances, between personal knowledge and social knowledge. It is the process of learning from experience that shapes and actualizes developmental potentialities. This learning is a social process; and thus, the course of individual development is shaped by the cultural system of social knowledge.

This position has been best articulated by the Soviet cognitive theorist, L. S. Vygotsky. He used the concept of the zone of proximal development to explain how learning shapes the course of development. The zone of proximal development is defined as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Cole et al., 1978, p. 86). The zone of proximal development is where learning occurs. Through experiences of imitation and communication with others and interaction with the physical environment, internal developmental potentialities are enacted and practiced until they are internalized as an independent development achievement. Thus, learning becomes the vehicle for human development via interactions between individuals with their biologic potentialities and the society with its symbols, tools, and other cultural artifacts. Human beings create culture with all its artificial stimuli to further their own development. Vygotsky’s ideas about how the tools of culture shape development were greatly influenced by Friedrich Engels, who saw culturally created tools as the specific symbol of man’s transformation of nature—that is, production. As Vygotsky himself put it:

The keystone of our method . . . follows directly from the contrast Engels drew between naturalistic and dialectical approaches to the understanding of human history. Naturalism in historical analysis, according to Engels, manifests itself in the assumption that only nature affects human beings and only natural conditions determine historical development. The dialectical approach, while admitting the influence of nature on men, asserts that man in turn affects nature and creates, through his changes in nature, new natural conditions for his existence. . . .

All stimulus response methods share the inadequacy that Engels ascribes to the naturalistic approach to history. Both see the relation between human behavior and history as unidirectionally reactive. My collaborators and I, however, believe that human behavior comes to have that “transforming reaction on nature” which Engels attributed to tools. [Cole et al., 1978, pp. 60–61]

It is this proactive adaptation that is the distinctive characteristic of human learning, a proactive adaptation that is made possible by the use of auxiliary cultural stimuli, social knowledge, to actively transform personal knowledge. For example, the symbolic tools acquired through the internalization of language allow us to anticipate, plan for, and practice reactions to upcoming situations in our life. As the tools of culture change, so too will the course of human development be altered (as with the widespread use of home computers; compare Papaert, 1980). In this sense, the laws and limitations of human development can never be known, since human nature is constantly emerging in the transaction between individuals and their culture.

The process of learning that actualizes development requires a confrontation and resolution of the dialectic conflicts inherent in experiential learning. The process is one that Paulo Freire describes as praxis—using dialogue to stimulate reflection and action on the world in order to transform it. Denis Goulet, in the introduction to Freire’s Education for Critical Consciousness, describes it this way:

Paulo Freire’s central message is that one can know only to the extent that one “problematizes” the natural, cultural and historical reality in which s/he is immersed . . . to “problematize” in his sense is to associate an entire populace to the task of codifying total reality into symbols which can generate critical consciousness and empower them to alter their relations with nature and social forces. This reflective group exercise . . . thrusts all participants into dialogue with others whose historical “vocation” is to become transforming agents of their social reality. Only thus do people become subjects, instead of objects, of their own history. [Freire, 1973, p. ix]

Differentiation and Integration in Development

From the dialectics of learning comes a human developmental progression marked by increasing differentiation and hierarchic integration of functioning. The concepts of differentiation and hierarchic integration are fundamental to virtually all theories of cognitive development and adult development. This principle of psychological development was borrowed from biological observations of evolution and development that show increasing physical differentiation and integration as one moves up the phylogenetic scale, particularly in the evolution of the nervous system.

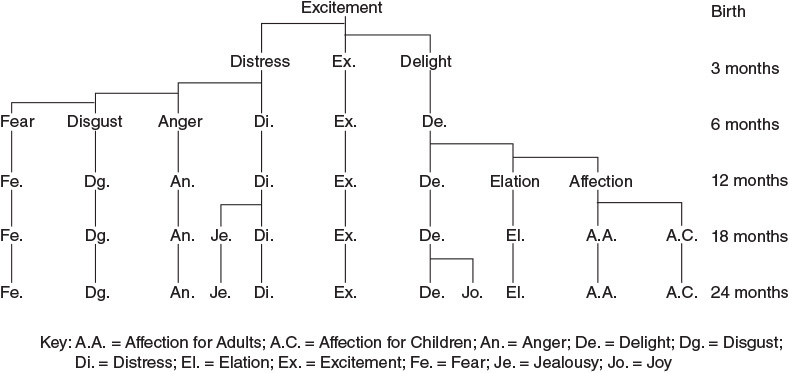

Differentiation has two aspects, an increasing complexity of units and a decreasing interdependence of parts. The course of learning and development is to refine, discriminate, and elaborate the categories of experience and the variety of behavior while at the same time increasing the independence of functioning among these separate parts. An example of differentiation can be seen in the development of the infant’s emotional life. In an early observational study of young children, Katherine Bridges (1932) described the increasing differentiation of the growing infant’s emotions from undifferentiated excitement to the basic distinction between distress and delight, to a refined spectrum of emotions encompassing fear, disgust, anxiety, jealousy, joy, parental affection, and so on (see Figure 6.1).

Source: Katherine Bridges, “Emotional Development in Early Infancy,” Child Development, 3 (1932).

Figure 6.1 Differentiation of Infant’s Emotional Life

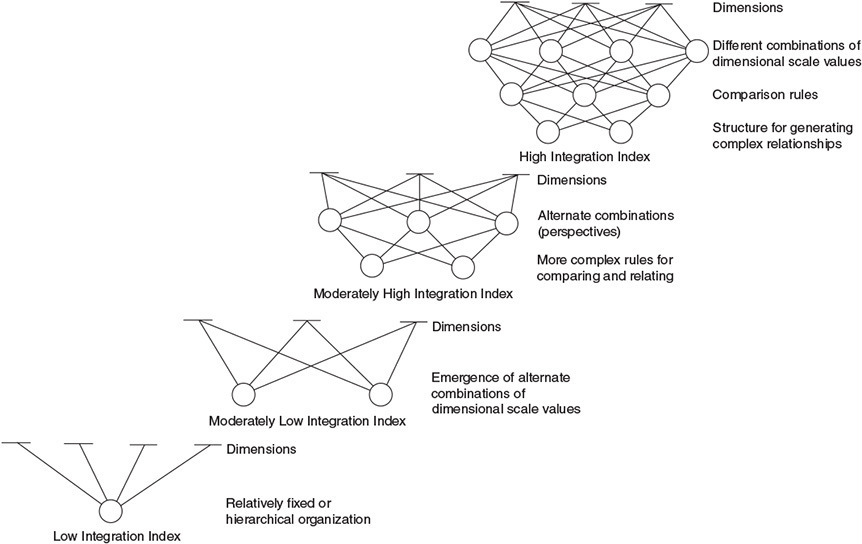

Hierarchic integration is the organism’s organizing response to the complexity and diffusion caused by increasing differentiation. Hierarchic integration is multilevel. At the first level are simple fixed rules for organizing differentiated dimensions of experience in an absolutistic way. For example, experience may be classified as either good or bad. At a somewhat higher level, alternative interpretive rules emerge, allowing for alternative interpretations of situations. The absolutistic right-wrong view of the world becomes somewhat more flexible by the use of simple contingency thinking; for instance, in situation A, this rule is true, but in situation B, another rule holds. At a still higher level, more complex rules than simple contingency thinking are developed for determining the perspective taken on experience. These rules are more “internalized,” free from fixed application based on past experience or the external stimulus. The highest level of integration adds still another system of rules that forms a structure for generating very complex relationships. This highest level allows great flexibility in the integration and organization of experience, making it possible to cope with change and environmental uncertainty by developing complex alternative constructions of reality. These four levels of hierarchic integration, as they are described by Schroder, Driver, and Streufert (1967), are shown graphically in Figure 6.2.

Source: H. M. Schroder, M. J. Driver, and S. Streufert, Human Information Processing (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1967).

Figure 6.2 Levels of Hierarchic Integration

Through hierarchic integration, the individual maintains integrity and wholeness through the creation of superordinate schema, including concepts, sentiments, acts, and observations. These schema organize and control the deployment of subordinate, differentiated concepts, sentiments, acts, and observations. In the example above of differentiation of the infant’s emotional life, the growing child develops progressively higher-order sentiments to control the application of these refined emotions to different settings and persons, introducing continuity and meaning to his or her experience. The unity and consistency of experience that at birth was the benefit of an undifferentiated view of the world must increasingly be purchased by integrative organizational efforts. Yet the dividends of these developmental processes are great—an increasingly conscious awareness and sophisticated control of ourselves in the world around us. In Lewin’s conception, integration was presumed to lag behind differentiation, producing cyclic patterns of development alternating between stages dominated by the diffusion of differentiation and stages dominated by the unity of hierarchic integration—a description not unlike Dewey’s advancing-army metaphor quoted earlier.

Unilinear vs. Multilinear Development

The experiential learning theory of development differs significantly from most Piaget-inspired theories of adult development in its emphasis on development as a multilinear process. The Piagetian theories of cognitive and adult development portray the course of development as unilinear, as some form of movement toward increasing differentiation and hierarchic integration of the structures that govern behavior. This is true of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development (Flavell, 1963), Loevinger’s theory of ego development (1976), Kohlberg’s theory of moral development (1969), Perry’s theory of moral and intellectual development (1970), the conceptual systems approach of Harvey, Hunt, and Schroeder (1961) and its derivatives by Hunt in education (1974), by Schroder et al. in information processing (1967), and by Harvey in personality theory (1966). Although experiential learning theory recognizes the overall linear trend in development from a state of globality and lack of differentiation to a state of increasing differentiation, articulation, and hierarchic integration, it takes issue with the exclusive linearity of the Piagetian approach in three respects.

First, it recognizes individual differences in the developmental process. In Piagetian schemes, individuality is manifest only in differential progression along the single yardstick of development—progression toward the internalized logic of scientific rationality. Individuals are different only insofar as they are at different stages of development. In experiential learning theory, however, individuality is manifest not only in the stage of development but also in the course of development—in the particular learning style the person develops. In this respect, the theory follows the Gestalt development approach of Heinz Werner:

The orthogenetic law, by its very nature, is an expression of unilinearity of development. But, as is true of the other polarities discussed here, the ideal unilinear sequence signified by the universal developmental law does not conflict with the multiplicity of actual developmental forms . . . coexistence of unilinearity and multiplicity of individual developments must be recognized for psychological just as it is for biological evolution. In regard to human behavior in particular, this polarity opens the way for a developmental study of behavior not only in terms of universal sequence, but also in terms of individual variations, that is, in terms of growth viewed as a branching-out process of specialization. . . . [Werner, 1948, p. 137]

A second difference arises from the transactional perspective of experiential learning that conceptualizes development as the product of personal knowledge and social knowledge. Since a person’s state of development is the product of the transaction between personal experience and the particular system of social knowledge interacted with, it is unreasonable to conceive of this state as solely a characteristic of the person, the view held by Piaget.1 The developmental structures observed in human thought are just as likely to be characteristics of the social knowledge system; thus the findings that children with Western schooling display Piaget’s developmental progressions more consistently than those whose schooling is embedded in other cultural knowledge systems (Bruner et al., 1966). This is an important proposition, for it argues that the paths of development can be as varied as the many systems of social knowledge. David Feldman has developed the ramifications of this view most thoroughly, suggesting a continuum of developmental regions ranging from the universals of intellect studied by Piaget (such as object permanance) through cognitive skills that are specific to a given culture, to a discipline-based knowledge system, and finally to idiosyncratic and unique capabilities that are developed by individuals through interactions with specialized or unique environments. Some of these unique accomplishments are judged to be creative, Feldman argues, and are fed back into the system of social knowledge, perhaps ultimately achieving disciplinary, cultural, or even universal status.

1. “We have seen that there exist structures that belong only to the subject, that they are built, and that this is a step-by-step process. We must therefore conclude that there exist stages of development” (Piaget, 1970a, p. 710).

Emphasis on the specialized paths of development leads to the third difference with Piagetian theories. For Piaget, all development is cognitive development. Experiential learning theory describes four development dimensions—affective complexity, perceptual complexity, symbolic complexity, and behavioral complexity—all interrelated in the holistic adaptive process of learning. The recognition of separate developmental paths helps to explain certain developmental phenomena that are anomalous in the Piagetian scheme. Werner gives one such example, the case of physiognomic perception. This affective mode of perceiving, in which perception and feeling are fused (for example, a gloomy landscape), is characteristic of young children but also seems to be highly developed in the adult artist:

To illustrate, “physiognomic” perception appears to be a developmentally early form of viewing the world, based on the relative lack of distinction between properties of persons and properties of inanimate things. But the fact that in our culture physiognomic perception, developmentally, is superseded by logical, realistic, and technical conceptualization poses some paradoxical problems, such as, What genetic standing has adult aesthetic experience? Is it to be considered a “primitive” experience left behind in a continuous process of advancing logification, and allowed to emerge only in sporadic hours of regressive relaxation? Such an inference seems unsound; it probably errs in conceiving human growth in terms of a simple developmental series rather than as a diversity of individual formations, all conforming to the abstract and general developmental conceptualization. Though physiognomic experience is a primordial manner of perceiving, it grows, in certain individuals such as artists, to a level not below but on a par with that of “geometric-technical” perception and logical discourse. [Werner, 1948, p. 138]

Similar questions can be raised about the highly developed intuitive and behavioral skill of the executive (Mintzberg, 1973), which resembles in structure the child’s trial-and-error enactive learning process.

Another example is what Turner (1973) calls recentered thinking, in which the relationship of social knowledge to the specific knowing individual must be established in order for people to particularize general cognitive principles. This particularization requires the synthesis of affective and cognitive components. Although Piaget’s developmental theory specifies how concepts gain independence from concrete experience, it does not specify the processes by which concepts are revisited with personal experience. In Piaget’s terms, assimilation ultimately takes priority over accommodation in his theory of development.

The final point of difference lies in the practical implications of the issues above. As was indicated in the first chapter, Piagetian theories have had a profound influence on American education, primarily through Jerome Bruner’s introduction of Piaget’s work at the prestigious Woods Hole conference on education in 1958. This conference, which framed our nation’s educational response to the Sputnik challenge, found in Piaget’s developmental theory the ideal framework for emphasizing and rationalizing the technoscientific dominance of education. In the race to regain the lead over the Soviets in technological supremacy, the educational system embraced scientific thinking as the way of knowing. Nurtured by federal largesse, educational institutions were transformed into technological institutions where scientific inquiry prospered and other approaches to knowing—the affective expression of the arts, the metaphysical reflection of philosophy and religion, and the integrative ideals of liberal education—all atrophied. Without in any way denigrating the intrinsic value or achievements of scientific inquiry, the multilinear developmental perspective of experiential learning suggests that science and technology alone are not enough. It rejects the view that other forms of inquiry must be subjected to science; that what ought to be is discovered in empirical investigation of what is; that the role of the humanities is to help us understand and cope with technological change rather than shape its directions. The true path toward individual and cultural development is to be found in equal inquiry among affective, symbolic, perceptual, and behavioral knowledge systems. Its intelligent direction requires integrated judgments about the future of humanity born from conflict and dialogue among these perspectives (compare Chapter 8, pp. 327–333).

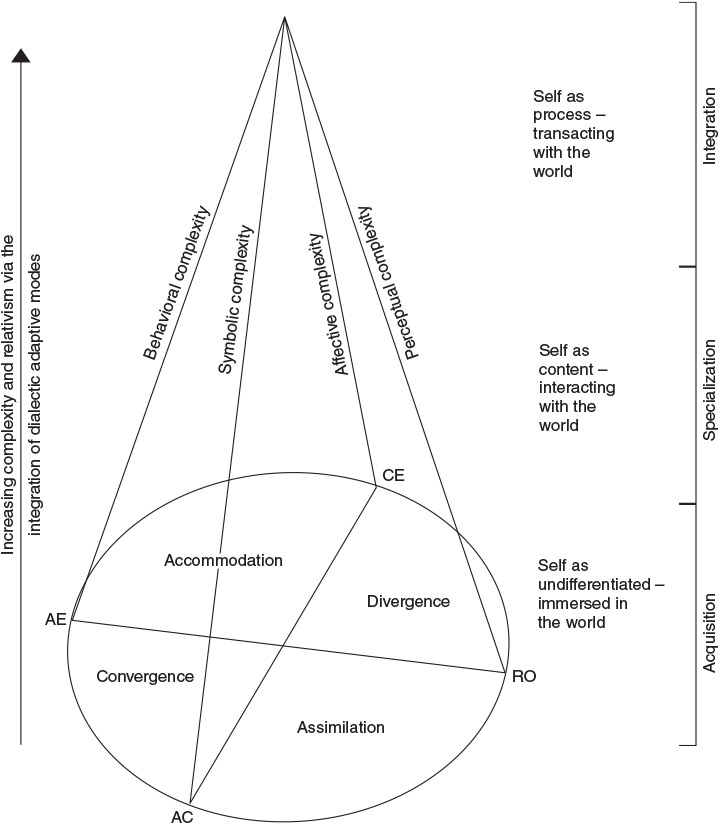

The Experiential Learning Theory of Development

The way learning shapes the course of development can be described by the level of integrative complexity in the four learning modes—affective complexity in concrete experience results in higher-order sentiments, perceptual complexity in reflective observation results in higher-order observations, symbolic complexity in abstract conceptualization results in higher-order concepts, and behavioral complexity in active experimentation results in higher-order actions. Figure 6.3 illustrates this experiential learning model of development. The four dimensions of growth are depicted in the shape of a cone, the base of which represents the lower stages of development and the apex of which represents the peak of development—representing the fact that the four dimensions become more highly integrated at higher stages of development. Development on each dimension proceeds from a state of embeddedness, defensiveness, dependence, and reaction to a state of self-actualization, independence, proaction, and self-direction. This process is marked by increasing complexity and relativism in dealing with the world and one’s experience and by higher-level integrations of the dialectic conflicts among the four primary learning modes. In the early stages of development, progress along one of these four dimensions can occur with relative independence from the others. The child and young adult, for example, can develop highly sophisticated symbolic proficiencies and remain naive emotionally. At the highest stages of development, however, the adaptive commitment to learning and creativity produces a strong need for integration of the four adaptive modes. Development in one mode precipitates development in the others. Increases in symbolic complexity, for example, refine and sharpen both perceptual and behavioral possibilities. Thus, complexity and the integration of dialectic conflicts among the adaptive modes are the hallmarks of true creativity and growth.

The human developmental process is divided into three broad development stages of maturation: acquisition, specialization, and integration. By maturational stages we refer to the rough chronological ordering of ages at which developmental achievements become possible in the general conditions of contemporary Western culture. Actual developmental progress will vary depending on the individual and his or her particular cultural experience. Even though the stages of the developmental growth process are depicted in the form of a simple three-layer cone, the actual process of growth in any single life history probably proceeds through successive oscillations from one stage to another. Thus, a person may move from stage 2 to stage 3 in several separate subphases of integrative advances, followed by consolidation or regression into specialization.

Stage One: Acquisition

This stage extends from birth to adolescence and marks the acquisition of basic learning abilities and cognitive structures. This, the most intensively studied period of human development, is described by Piaget as having four major substages (Chapter 2, pp. 34–36). The first stage, from birth until about 2 years, is called the sensorimotor stage, because learning is primarily enactive; that is, knowledge is externalized in actions and the feel of the environment. Thus, accommodative learning, apprehension transformed by extension, is the dominant mode of adaptation. The second stage, from 2 to 6 years, is called the iconic stage, because at this point, internalized images begin to have independent status from the objects they represent. It is at this stage that early forms of divergent learning, apprehension transformed by intention, are acquired. The third stage, from 7 to 11 years, marks the beginning of symbolic development in what Piaget calls the stage of concrete operations. Here the child begins development of the logic of classes and relations and inductive powers—in other words, assimilative learning via the transformation of comprehension by intention. The final stage of development in Piaget’s scheme occurs in adolescence (12 to 15 years). Here, symbolic powers achieve total independence from concrete reality in the development of representational logic and the process of hypothetical deductive reasoning. These powers enable the child to imagine or hypothesize implications of purely symbolic systems and test them out in reality—convergent learning via transformation of comprehensions by extension. Development in the acquisition phase is marked by the gradual emergence of internalized structures that allow the child to gain a sense of self that is separate and distinct from the surrounding environment. This increasing freedom from undifferentiated immersion in the world begins with basic discrimination between internal and external stimuli and ends with that delineation of the boundaries of selfhood that Erikson (1959) has called the identity crisis.

Stage Two: Specialization

This stage extends through formal education and/or career training and the early experiences of adulthood in work and personal life. People shaped by cultural, educational, and organizational socialization forces develop increased competence in a specialized mode of adaptation that enables them to master the particular life tasks they encounter in their chosen career (in the broadest sense of the word) paths. Although children in their early experiences in family and school may already have begun to develop specialized preferences and abilities in their learning orientations (see Hudson, 1966), in secondary school and beyond they begin to make choices that will significantly shape the course of their development. The choice of college versus trade apprenticeship, the choice of academic specialization, and even such cultural factors as the choice of where to live begin to selectively determine the socialization experiences people will have and thereby influence and shape their mode of adaptation to the world. The choices a person makes in this process tend to have an accentuating, self-fulfilling quality that promotes specialization.

In the experiential learning theory of adult development, stability and change in life paths are seen as resulting from the interaction between internal personality dynamics and external social forces in a manner much like that described by Super et al. (1963). The most powerful developmental dynamic that emerges from this interaction is the tendency for there to be a closer and closer match between self characteristics and environmental demands. This match comes about in two ways: (1) Environments tend to change personal characteristics to fit them (socialization), and (2) people tend to select themselves into environments that are consistent with their personal characteristics. Thus, development in general tends to follow a path toward accentuation of personal characteristics and skills (Feldman and Newcomb, 1969; Kolb and Goldman, 1973), in that development is a product of the interaction between choices and socialization experiences that match these choice dispositions such that resulting experiences further reinforce the same choice disposition for later experience. This process is inherent in the concept of learning styles as possibility-processing structures that govern transactions with the environment and thereby define and stabilize individuality.

Thus, in the specialization stage of development, the person achieves a sense of individuality through the acquisition of a specialized adaptive competence in dealing with the demands of a chosen “career.” One’s sense of self-worth is based on the rewards and recognition received for doing “work” well. The self in this stage is defined primarily in terms of content—things I can do, experiences I have had, goods and qualities I possess. The primary mode of relating to the world is interaction—I act on the world (build the bridge, raise the family) and the world acts on me (pays me money, fills me with bits of knowledge), but neither is fundamentally changed by the other. Paulo Freire describes this stage-2 sense of self and the “banking” concept of education that serves to reinforce it:

Implicit in the banking concept is the assumption of a dichotomy between man and the world: Man is merely in the world, not with the world or with others; man is spectator, not re-creator. In this view, man is not a conscious being; he is rather the possessor of a consciousness; an empty “mind” passively open to the reception of deposits of reality from the world outside. . . . This view makes no distinction between being accessible to consciousness and entering consciousness. The distinction, however, is essential: The objects which surround me are simply accessible to my consciousness not located within it.

It follows logically from the banking notion of consciousness that the educator’s role is to regulate the way the world “enters into” the students. His task is to organize a process which already occurs spontaneously, to “fill” the students by making deposits of information which he considers to constitute true knowledge. And since men “receive” the world as passive entities, education should make them more passive still, and adapt them to the world. The educated man is the adapted man, because he is better “fit” for the world. [Freire, 1974, p. 62]

Stage Three: Integration

The specialized developmental accomplishments of stage 2 bring social security and achievement, often paid for by the subjugation of personal fulfillment needs. The restrictive effects that society’s socializing institutions have on personal fulfillment have been a continuing theme of Western thought, particularly since the Enlightenment. Freud and his followers in psychoanalysis developed the socioemotional dimensions of this conflict between individual and society—libidinous instincts clashing with repressive social demands. In modern organization theory, this conflict has been most clearly articulated by Argyris (1962). Yet it is Carl Jung’s formulation of this conflict and the dimensions of its resolution in his theory of psychological types that is most relevant here. The Jungian theory of types, like the experiential learning model, is based on a dialectic model of adaptation to the world. Fulfillment, or individuation, as Jung calls it, is accomplished by higher-level integration and expression of nondominant modes of dealing with the world. This drive for fulfillment, however, is thwarted by the needs of civilization for specialized role performance.

The needs of Western specialized society have long stood in conflict with individuals in their drive for integrative development. In 1826, the German poet and historian, Friedrich Schiller, wrote:

When the commonwealth makes the office or function the measure of the man; when of its citizens it does homage only to the memory in one, to a tabulating intelligence in another, and to a mechanical capacity in a third; when here, regardless of character, it urges only towards knowledge while there it encourages a spirit of order and law-abiding behavior with the profoundest intellectual obscurantism—when, at the same time, it wishes these single accomplishments of the subject to be carried to just as great an intensity as it absolves him of extensity—is it to be wondered at that the remaining faculties of the mind are neglected, in order to bestow every care upon the special one which it honors and rewards? [Schiller, 1826, p. 23]

Commenting on this passage by Schiller, Jung says:

The favoritism of the superior function is just as serviceable to society as it is prejudicial to the individuality. This prejudicial effect has reached such a pitch that the great organizations of our present day civilization actually strive for the complete disintegration of the individual, since their very existence depends upon a mechanical application of the preferred individual functions of men. It is not man that counts but his one differentiated function. Man no longer appears as man in collective civilization; he is merely represented by a function—nay, further, he is even exclusively identified with this function and denied any responsible membership to the level of a mere function, because this it is what represents a collective value and alone affords a possibility of livelihood. But as Schiller clearly discerns, differentiation of function could have come about in no other way: “There was no other means to develop man’s manifold capacities than to set them one against the other. This antagonism of human qualities is the great instrument of culture; it is only the instrument, however, for so long as it endures man is only upon the way to culture.” [Jung, 1973, p. 94]

The transition from stage 2 to stage 3 of development is marked by the individual’s personal, existential confrontation of this conflict. The personal experience of the conflict between social demands and personal fulfillment needs and the corresponding recognition of self-as-object precipitates the individual’s transition into the integrative stage of development. The experience can develop as a gradual process of awakening that parallels specialized development in stage 2, or it can occur dramatically as a result of a life crisis such as divorce or losing one’s job. Some may never have this experience, so immersed are they in the societal reward system for performing their differentiated specialized function.

With this new awareness, the person experiences a shift in the frame of reference used to experience life, evaluate activities, and make choices. The nature of this shift depends upon the specifics of the person’s dominant and nonexpressed adaptive modes. For the reflective person, the awakening of the active mode brings a new sense of risk to life. Rather than being influenced, one now sees opportunities to influence. The challenge becomes to shape one’s own experience rather than observing and accepting experiences as they happen. For the person who has specialized in the active mode, the emergence of the reflective side broadens the range of choice and deepens the ability to sense implications of actions. For the specialist in the concrete mode, the abstract perspective gives new continuity and direction to experience. The abstract specialist with a new sense of immediate experience finds new life and meaning in abstract constructions of reality. The net effect of these shifts in perspective is an increasing experience of self as process. A learning process that has previously been blocked by the repression of the nonspecialized adaptive modes is now experienced deeply to be the essence of self.

Consciousness, Learning, and Development

In the experiential learning model of development, there are three distinct levels of adaptation, representing successively higher-order forms of learning. These forms of learning are governed by three qualitatively different forms of consciousness. We will refer to these three levels of adaptation as performance, learning, and development.

In the acquisition phase of development, adaptation takes the form of performance governed by a simple registrative consciousness. In the specialization phase of development, adaptation occurs via a learning process governed by a consciousness that is increasingly interpretative. The integrative phase of development marks the achievement of a holistic developmental adaptive process governed by a consciousness that is integrative in its structure. Thus, each developmental stage of maturation is characterized by acquisition of a higher-level structure of consciousness than the stage preceding it, although earlier levels of consciousness remain; that is, adults can display all three levels of consciousness: registrative, interpretative, and integrative. These consciousness structures govern the process of learning from experience through the selection and definition of that experience.

How Learning Shapes Consciousness

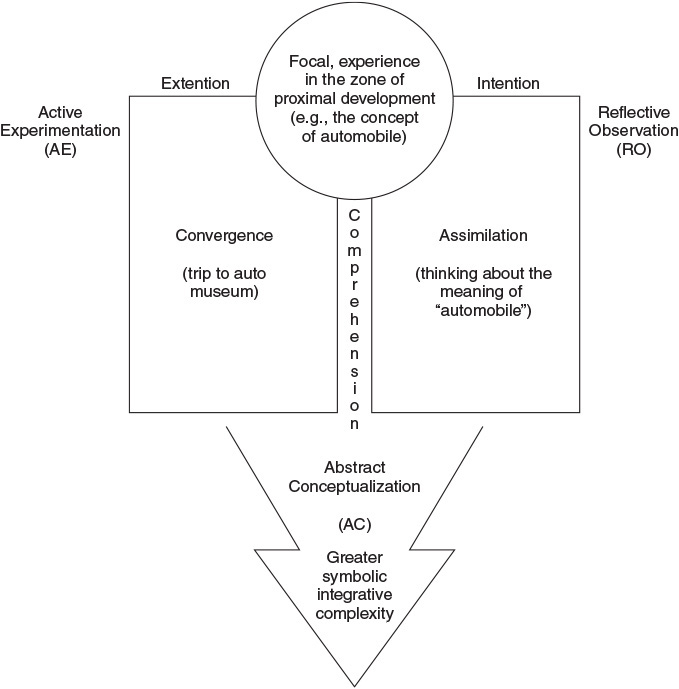

To understand the role of consciousness in learning and development requires further examination of the structural learning model proposed earlier. Previous chapters have described four elementary forms of learning—accommodation, assimilation, convergence, and divergence—and alluded to higher-order forms of learning that emerge from combinations of these elementary forms. In the developmental terms of differentiation and integration, the elementary learning processes are the primary means for differentiation of experience; the higher-order combinations of the elementary forms represent the integrative thrust of the learning process. The conscious focus of experience that is selected and shaped by one’s actual developmental level is refined and differentiated in the zone of proximal development by grasping and transforming it.

To illustrate, take the example of my recent trip to the auto museum. Preoccupied as I was with explaining how learning from experience is developmental, I found myself during the visit focusing on how I was developing my concept of automobile. First, I walked around and found many forms and variations of cars to refine and elaborate the concept; here I was learning via convergence, differentiating my concept through extension. Later I began learning about automobiles via assimilation, intensively transforming the concept to search for its precise meaning and critical attributes: How is an auto different from a bicycle? Must an automobile have an engine? In both cases, I was differentiating my conscious experience of the automobile concept.

Integrative learning occurs when two or more elementary forms of learning combine to produce a higher-order integration of the elementary differentiations around their common learning mode(s). In the automobile example, if I use the assimilative and convergent forms of learning together, I search the museum for cars without engines and find none, although I do find a tricycle-like contraption with a small motor. The result is an incremental increase in the symbolic integrative complexity of my concept of automobile. Not only do I have a more extensive population of cars in my concept (acquired via convergence) and a more refined elaboration of the essential and nonessential attributes of the concept (acquired via assimilation), but in their combination, my comprehension of automobiles is increased. In determining that automobiles have some form of self-propulsion as an essential attribute and that “looking like a bicycle” is a nonessential attribute, my automobile concept has become more complex and integrated—an increase in actual developmental level. As such, it now asserts a greater measure of control over the choice and definition of my future focal experiences; for example, I now begin to see motorcycles as a special subcategory of automobiles.

In serving as the integrative link between dialectically opposed learning orientations, the common learning mode of any pair of elementary learning forms becomes more hierarchically integrated, thereby giving that common learning orientation a greater measure of organization and control over the person’s experience. This process is depicted in Figure 6.4 using the automobile example. Here, in the classic confrontation of the dialectic between intention and extension of a concept, we find a unique resolution via the refinement of the concept to encompass greater differentiation via hierarchic integration—that is, an increase in symbolic integrative complexity.

Similar increases in hierarchic integration of the common learning mode occur with other pairs of elementary learning forms. When convergence and accommodation combine, the result is an increase in behavioral integrative complexity via the resolution of the dialectic between comprehension and apprehension. In the pool-playing example cited in Chapter 4, convergent problem solving suggesting that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, combined with the accommodative feel of the table, the cue stick, and the position of the balls produces refined behavioral skills in controlling the course of the cue ball. This refinement results from the comprehension of the basic laws of physics and the apprehension of the internal body cues and external physical circumstances integrated through extension—behavioral acts that operationalize the abstract concept in the concrete physical setting. The behavioral acts are guided and refined by a negative feedback loop between the goal defined by comprehension and the actual circumstance experience by apprehension; I keep practicing until I can hit the ball to the position I predict.

When the elementary learning forms of accommodation and divergence combine, the result is an increase in affective integrative complexity via the resolution of the dialectic between intention and extension. The artist stands before the canvas, brush in hand, experiencing a flow of images and feelings (divergence). The stroke of color applied (accommodation) externalizes the internal flow of experience, creating a frozen record of a dynamic process. The extent to which the stroke is successful in capturing that internal process is measured by its ability to recreate the internal gestalt of the moment of its birth, thus allowing the wholeness of that re-created experience to carry forward into the second stroke . . . and the third. It is from this cycle of action and reaction that sentiments are crystalized and refined, sentiments whose level of development is measured by their ability to sustain and carry forward experience (Gendlin, 1964).

The combination of the divergent and assimilative learning forms produces increases in perceptual integrative complexity via the resolution of the dialectic between apprehension and comprehension. The inductive model building of assimilation in combination with the apprehended observations of divergence produces more integratively complex categories of perception. Detective stories offer numerous examples of the synthesis of these two elementary learning forms, wherein the investigator is simultaneously inducing scenarios of how the crime was committed from the clues gathered and creating new clues and observations by juxtaposing scenarios with actual events. The creative synthesis of the comprehended scenario and apprehended events is illustrated by the fact that these new observations are not only about what happened but also about what did not happen but should have happened if a given scenario or alibi were correct. Thus, higher-order perceptual observations are not carbon copies of reality but integrations of what “is” and what “ought to be.”

Registrative, Interpretative, and Integrative Consciousness

To illustrate further the levels of consciousness in learning, let us return to my automobile museum trip. The focal experience in this case was my concept of automobile. In my learning from that experience using the elementary convergent form of learning, my comprehension of the automobile concept was extended by my examination of the array of cars in the local auto museum. In this process, the concept of automobile was elaborated via a consciousness that was basically registrative. Each car I examined was “filed away” as another instance of an automobile. The focal experience “concept of automobile” did not change but was elaborated through grasping it via comprehension and transforming it via extension. When this convergent learning process was combined with assimilation (thinking about the meaning and critical attributes of the concept of automobile), my consciousness took on an interpretive quality that began to alter the focal experience itself; that is, the combination of these two learning forms produced an increase in the symbolic complexity of my concept “automobile,” which in turn modified the focal experience to include bicycle-like self-propelled vehicles.

This second-level interpretative consciousness has two important characteristics that are lacking in the first-level registrative consciousness associated with the elementary learning forms. First, the combination of the two elementary learning modes creates an evaluative process that selectively interprets the focal experience. This is accomplished in the dialectic resolution of opposing learning modes (intention and extension, in the auto example). Second, this interpretation of the focal experience alters it selectively, redefining it and carrying it forward in terms of the hierarchically integrated learning mode. The combination of assimilative and convergent learning about the concept automobile refined the concept and enhanced the abstract/symbolic focus of the experience.

Thus the (second) interpretative level of consciousness associated with pairwise combinations of the elementary learning forms serves to define and shape the flow of experience, channeling it into more highly integrated forms of affective, perceptual, symbolic, and behavioral complexity. This level of consciousness gives direction and structure to the unfocused elaboration of registrative consciousness. But how then is the direction of the interpretative level of consciousness determined? How does one choose what experience to attend to and how to define it, either affectively, perceptually, symbolically, or behaviorally? In the absence of third-order integrative consciousness, the process is the one of random accentuation described in the specialization phase of development. An experience is chosen (concept of automobile) that “pulls for” a particular orientation (comprehension), and the refinement of the orientation (via increases in symbolic complexity) further increases the “pull” for that orientation, creating a positive feedback loop that serves to channel experience more and more in that direction.

Integrative consciousness introduces purpose and focus to this random process via integration of the opposition between the grasping dialectic of apprehension and comprehension and the transformation dialectic of intention and extension. This “centering” of experience, although not easily achieved, serves to answer the more strategic questions of life, such as, why think about automobiles anyway? And why focus on the concept of automobile as opposed to the apprehension and aesthetic appreciation of particular cars? In this particular case, I choose automobiles more or less randomly to illustrate a point about the learning process. I choose to focus on the “concept” of automobile because the example of the dialectic between intention and extension is clearest for abstract concepts (see Chapter 3, pp. 77–78). As I now try to push the example to explain integrative consciousness, I experience a kind of “stuckness.” The example seems academic, trivial, and unrelated to me personally; I am lacking any apprehension about the focal experience, “concept of automobile.” In searching for this personal relevance, I recall thinking, at the museum, that I would like to own a classic car, and further, that I often pause in airports to admire and get literature about those classic-car kits one builds on a Volkswagen chassis. On impulse, I have even bought a set of mechanic’s tools with this idea vaguely in mind. By my bringing these accommodative learning experiences to bear on my conscious focal experience, its nature changes to include apprehensions of my personal feelings and desires about cars. The focal experience changes from concept of car to include specific cars and my relation to them, including the attractive fantasy of building one from a classic-car kit. Suddenly I begin to experience questions, and a fourth perspective on the experiences emerges—divergence, the transformation of these apprehensions by intention. How much of my self-image, money, and time do I really want to invest in a car? There is something vaguely decadent and ostentatious about fancy cars. And come to think of it, the whole concept of a self-propelled vehicle makes little sense in my life, where most things are close by and I need the exercise.

Even though this example may be a bit strained, it serves to illustrate the nature of integrative consciousness. To interpretative consciousness, integrative consciousness adds a holistic perspective. Interpretative consciousness is primarily analytic; experiences can be treated singly and in isolation. Integrative consciousness is primarily synthetic, placing isolated experiences in a context that serves to redefine them by the resulting figure-ground contrasts. Another feature of integrative consciousness is its scope. Its concern is more strategic than tactical, and as a result, issues in integrative consciousness are defined broadly in time and space. Finally, integrative consciousness creates integrity by centering and carrying forward the flow of experience. This centering of experience is created by a continuous learning process fueled by successive resolutions of the dialectic between apprehension and comprehension and intention and extension.

Adaptation, Consciousness, and Development

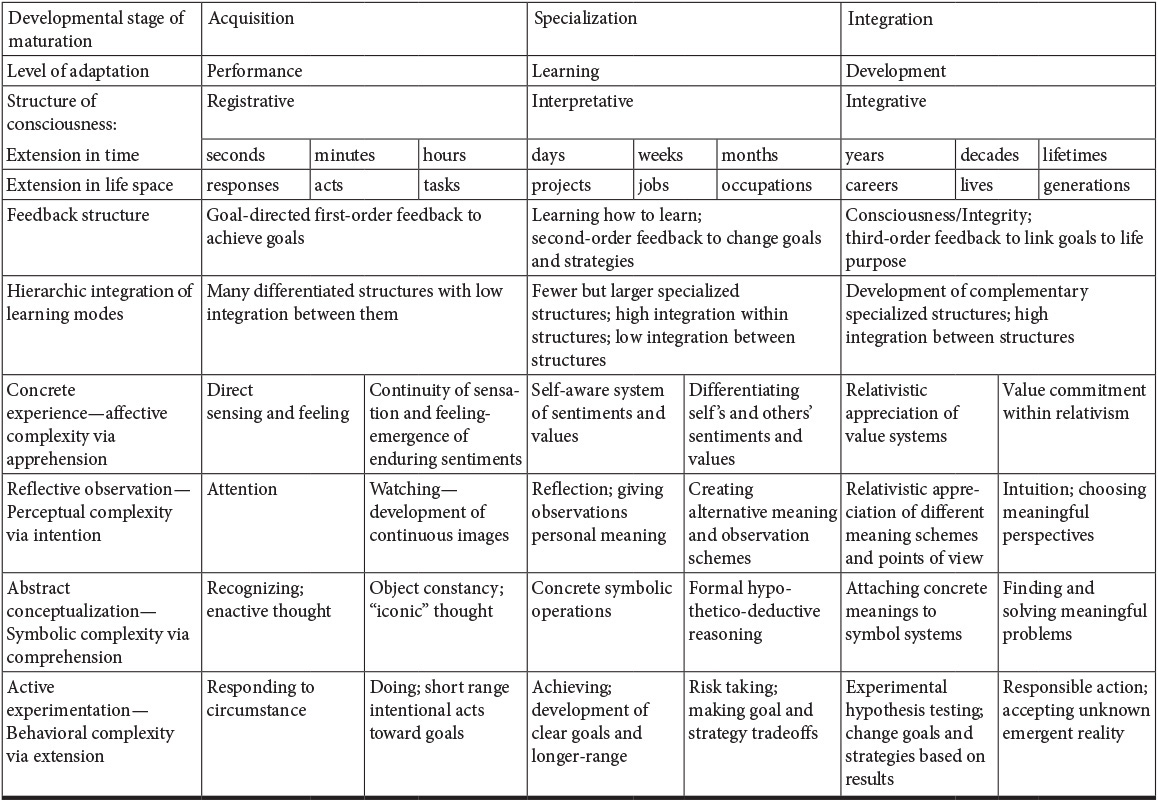

With this example as a starting point, let us now turn to a more systematic formulation of the interrelationships among the stages of developmental maturation, the levels of adaptation, and the structure of consciousness as summarized in Table 6.1. It was Kurt Lewin who first articulated how consciousness increases in time/space extension with developmental maturation:

Table 6.1 Experiential Learning Theory of Development: Levels of Adaptation and the Structure of Consciousness

The three-month-old child living in a crib knows few geographical areas around him, and the areas of possible activities are comparatively few. The child of one year is familiar with a much wider geographical area and a wider field of activities. He is likely to know a number of rooms in the house, the garden, and certain streets. . . .

During development, both the space of free movement and the life space usually increase. The area of activity accessible to the growing child is extended because his own ability increases, and it is probable that social restrictions are removed more rapidly than they are erected as age increases, at least beyond the infant period. . . . The widening of the scope of the life space occurs sometimes gradually, sometimes in rather abrupt steps. The latter is characteristic for so-called crises in development. This process continues well into adulthood.

A similar extension of the life space during development occurs in what may be called the “psychological time dimension.” During development, the scope of the psychological time dimension of the life space increases from hours to days, months, and years. In other words, the young child lives in the immediate present; with increasing age, an increasingly more distant psychological past and future affect present behavior. [Lewin, 1951, pp. 103–104]

As the extension of consciousness increases, the same behavioral action is imbued with broader significance, representing an adaptation that takes account of factors beyond the immediate time and space situation. The infant will instinctively grasp the shiny toy before it; the young child may hesitate before picking up her brother’s toy gun, knowing it will make him angry; an adult may ponder the purchase of that same toy gun, considering the moral implications of letting her child play with guns. Thus, what is considered the correct or appropriate response will vary depending on the conscious perspective used to judge it. When we judge performance, our concern is usually limited to relatively current and immediate circumstances. When we judge learning, the time frame is extended to evaluate successful adaptation in the future, and the situational circumstance is enlarged to include generically similar situations. When we evaluate development, the adaptive achievement is presumed to apply in all life situations throughout one’s lifetime; and if the achievement is recorded as a cultural “tool,” the developmental scope may extend even beyond one’s lifetime.

Along with this relatively continuous expansion of the scope of consciousness, there are also discontinuous qualitative shifts in the organization of consciousness as growth occurs. These shifts represent the hierarchic addition of more complex information-processing structures, giving consciousness an interpretative and integrative capability to supplement the simple registrative consciousness of infancy. William Torbert, in his seminal book, Learning from Experience: Toward Consciousness, has described the hierarchic structure of consciousness as a three-tiered system of higher-order feedback loops. As in our approach, he uses this three-level structure of consciousness to solve problems that arise in explaining how the focus of experience (what constitutes feedback, in his terms) is determined. He explains his model as follows:

Recognition of these problems [of what constitutes feedback] has led social systems theorists to attempt to deal with them by postulating two orders of feedback over and above goal-directed feedback (Deutsch, 1966; Mills, 1965). Goal-directed feedback is referred to as first-order feedback. Its function is to redirect a system as it negotiates its outer environment towards a specific goal. The goals and boundaries of the system are assumed to be defined, so feedback is also defined. . . . The two higher orders of feedback can be viewed as explaining how goals and boundaries come to be defined. Second-order feedback has been named “learning” by Deutsch. Its function is to alert the system to changes it needs to make within its own structure to achieve its goal. The change in structure may lead to a redefinition of what the goal is and always leads to a redefinition of the units of feedback (Buckley, 1967). Third-order feedback is called “consciousness” by Deutsch. Its function is to scan all system-environment interactions immediately in order to maintain a sense of the overall, lifetime, autonomous purpose and integrity of the system.

The terms “purpose” and “integrity,” critical to the meaning of “consciousness,” can be elaborated as follows: The “inner” conscious purpose can be contrasted to the “external” behavioral goal. Goals are subordinate to one’s purpose. Goals are related to particular items and places, whereas purpose relates to one’s life as a whole, one’s life as act. Purpose has also been termed “intention” (Husserl, 1962; Miller, Galanter, and Pribram, 1960) and can be related to the literary term “personal destiny.”

The concept of integrity can be related to Erikson’s (1959) life-stage that has the same name. A sense of integrity embraces all aspects of a person, whereas the earlier life-stage in Erikson’s sequence, named “identity,” represents the glorification of certain elements of the personality and the repudiation of others (Erikson, 1958, p. 54). The distinction between a system’s identity and a system’s integrity can be sharpened by regarding identity as the particular quality of a system’s structure, whereas integrity reflects the operation of consciousness. In this sense, consciousness provides a system with “ultrastability” (Cadwallader, 1968). Ultrastability gives the system the possibility of making changes in its structure because the system’s essential coherence and integrity are not dependent upon any given structure. [Torbert, 1972, pp. 14–15]

A simple example will illustrate these three levels of feedback and their interrelationship in determining behavior. The classic example of first-order feedback is the household thermostat. The setting of the thermostat represents the goal, and the built-in thermometer is the sensory receptor that starts the furnace when the reading is below the setting and stops it when the set temperature is reached. A similar thermostat inside the human body performed this same registrative function of consciousness in our earlier time, when feeling cold led our ancestors to throw another log on the fire. Second-order feedback is created by the structure that governs how we set the thermostat. One person may set the thermostat at 70°F. The decision is based on a structure designed to maximize personal comfort. Another person may set the thermostat at 65°F. Her decision is based on a structure designed to save money. The units of feedback here are dollars. Thus, second-order feedback structures are interpretive, governing both goals and the meaning (units) of feedback. Most of us share in some degree both these personal-comfort and economic structures, as well as others based on patriotic energy conservation, concern for one’s health, and so on. Third-order feedback provides the integrative perspective or integrity that allows for consistent choice about which structure or combination of structures to apply to this particular problem. It governs the process whereby we trade off the values and units of feedback defined by noncompatible structures and answer such questions as, how much will I pay to avoid feeling chilly at times? and, how much personal comfort will I sacrifice for the good of the planet?

The thermostat is a good model for registrative consciousness. Events are registered in consciousness on the basis of a structure that defines goals and units of feedback, but at this first level of consciousness we have no awareness of the higher-level structure that governs the process of registering experience. We respond automatically in terms of that structure, just as a thermostat would respond by turning on the furnace when it got dark if we replaced the thermometer with a light sensor. We undoubtedly share this first level of consciousness with the higher animals, whose second-order interpretive structures are largely instinctively determined. At this level of consciousness, the hierarchic integration of the four learning modes is low. Concrete experience is limited to stimulus-bound sensations and feelings. The emergence of enduring sentiments that exist in the absence of their referent sets the stage for the beginning of interpretive consciousness. Similarly, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation are all immediate and bound up in the stimulus situation in the first stage of registrative consciousness, and they move toward a constancy of images, concepts, and actions as interpretative consciousness begins.

With the hierarchic integration of the four learning modes and increasing affective, perceptual, symbolic, and behavioral complexity come the emergence of interpretative consciousness and second-order “learning” feedback.2 This is the distinctively human consciousness that most of us associate with the term. In addition to the simple registration of experience, there is an awareness of an “I” who is doing the registering and guiding the choice and definition of a focal experience. As we have seen, this control of the choice and definition of our experiences is achieved by the development of higher-order sentiments, observations, concepts, and actions that interpret experience selectively. These highest-order structures can be seen as learning heuristics that control the definition and elaboration of experience by giving a priori preference to some interpretations over others.

2. The reason that other animals do not develop the higher levels of consciousness may lie in the fact that they lack the symbolic comprehension powers associated with the left brain and thus cannot participate in the triangulation of experience that results from the dialectic between apprehension and comprehension producing hierarchic integration of experience.

An example of how learning heuristics operate to interpret consciousness is found in Adriaan de Groot’s (1965) research on how chess masters and novices perceive game situations and formulate chess strategy. It was originally thought that chess masters were more skilled than novices because they thought further ahead and examined more possible moves. It turns out that masters do not think further ahead and, in fact, examine only a few possible moves. Instead, they think about the game at a higher level than novices do, perceiving grouped patterns of pieces that act as a kind of filter to ignore “bad” moves, much as an amateur might use similar but simpler patterns in order not to perceive illegal moves, such as moving the rook diagonally. These higher-level learning heuristics serve to simplify and refine moves in the game by eliminating from consideration a vast array of potential moves that are of little value in viewing the game. Harry Harlow (1959) has argued that all learning is based on this process of inhibiting incorrect responses, creating internalized programs or learning sets that selectively interpret new experiences.

With specialized development, each learning mode organizes clusters of learning heuristics based upon that particular learning orientation. With increased affective complexity comes a self-aware system of sentiments and values to guide one’s life, a system that at higher levels becomes differentiated from a growing awareness of the values and sentiments of others. Increasing perceptual complexity is reflected in the development of perspectives on experience that have personal meaning and coherence. At higher levels of interpretative consciousness, one develops the ability to observe experience from multiple perspectives. Increasing symbolic complexity results first in Piaget’s stage of concrete symbolic operations and later in formal hypothetico-deductive reasoning. Increased behavioral complexity results in achievement/action schemes—longer-term goals with complex action strategies to reach them. At higher levels of behavioral complexity, these action schemes are combined and traded off in a process that recognizes the necessity of risk taking.

Integrative consciousness based on third-order feedback represents the highest level of hierarchic integration of experience. In Torbert’s view, it is a level of consciousness that few achieve in their lifetime. The reason that integrative consciousness is so difficult to achieve is that interpretative consciousness has a self-sealing, self-fulfilling character that deceives us with the illusion of a holistic view of an experience when it is in fact fragmented and specialized (see Argyris and Schon, 1978). Precisely because interpretative consciousness selects and defines the flow of experience by excluding aspects of the experience that do not fit its structure, interpretative consciousness contains no contradictions that would challenge the validity of the interpretation. The person highly trained in, say, the symbolic interpretation of her experience rests at the center of that interpretative consciousness confident of the certainty and sufficiency of her view of the world. It is only at the margins that this view seems shaky, as with logical analysis of personal relationships; and only the most advanced forms of symbolic inquiry, such as Gödel’s theorem in logic, call its comprehensive application into question.

To achieve integrative consciousness, one must first free oneself from the domination of specialized interpretative consciousness. Jung called this transition to integrative consciousness the process of individuation, whereby the adaptive orientations of the conscious social self are integrated with their complementary nonconsciousness orientations. In Psychological Types, he gives numerous examples of the power of the dominant conscious orientation (interpretative consciousness, in our terms) in thwarting this integration and of the strong measures needed to overcome it:

For there must be a reason why there are different ways of psychological adaptation; evidently one alone is not sufficient, since the object seems to be only partly comprehended when, for example, it is either merely thought or felt. Through a one-sided (typical) attitude there remains a deficit in the resulting psychological adaptation, which accumulates during the course of life; from this deficiency a derangement of adaptation develops which forces the subject towards a compensation. But the compensation can be obtained only by means of amputation (sacrifice) of the hitherto one-sided attitude. Thereby a temporary heaping up of energy results and an overflow into channels hitherto not consciously used though already existing unconsciously. [Jung, 1973, p. 28]

Jung’s prescription for the amputation of the dominant function is dramatized by his illustrative example of Origin, a third-century Christian convert from Alexandria, who marked his conversion by castration so that, in Origin’s words, “all material things” could be “recast through spiritual interpretation into a cosmos of ideas.” Betty Edwards, in her system for learning to draw by using the right side of the brain, suggests a less drastic approach for getting around the dominance of the specialized left-brain interpretative consciousness.

Since drawing a perceived form is largely a right brain function, we must keep the left brain out of it. Our problem is that the left brain is dominant and speedy and is very prone to rush in with words and symbols, even taking over jobs which it is not good at. The split brain studies indicated that the left brain likes to be boss, so to speak, and prefers not to relinquish tasks to its dumb partner unless it really dislikes the job—either because the job takes too much time, is too detailed or slow or because the left brain is simply unable to accomplish the task. That’s exactly what we need—tasks that the dominant left brain will turn down. [Edwards, 1979, p. 42]

Because we are ensnared by our particular specialized interpretative consciousness and reinforced for this entrapment through the specialized structure of social institutions, we know little of the nature of integrative consciousness. Most descriptions of this state have come from the mystical or transcendental religious literature, descriptions that fall on deaf ears for those at the interpretative level of consciousness who find the rapturous prose about “golden flowers” and the “Clear Light” to be so much baloney. The problem, of course, is that integrative consciousness by its very nature cannot be described by any single interpretation. Thus, all these descriptions have an elusive and even contradictory quality, such as that which characterizes Zen Koans. For example:

Jōshū asked the teacher, Nansen, “What is the true Way?”

Nansen answered, “Everyday; way is the true Way.”

Jōshū asked, “Can I study it?” Nansen answered, “The more you study, the further from the Way.”

Jōshū asked, “If I don’t study it, how can I know it?”

Nansen answered, “The Way does not belong to things seen: Nor to things

unseen. It does not belong to things known: Nor to things unknown. Do not

seek it, study it, or name it. To find yourself and it, open yourself wide as the sky.

[Zen Buddism, 1959, p. 22]

The transcendent quality of integrative consciousness is precisely that, a “climbing out of” the specialized adaptive orientations of our worldly social roles. With that escape come the flood of contradictions and paradoxes that interpretative consciousness serves to stifle. It is through accepting these paradoxes and experiencing their dialectical nature fully that we achieve integrative consciousness in its full creative force. This state of consciousness is not reserved for the monastery but is a necessary ingredient for creativity in any field. Albert Einstein once said, “The most beautiful and profound emotion one can feel is a sense of the mystical. . . . It is the dower of all true science.”

In accepting and experiencing fully the dialectic contradictions of experience, one’s self becomes identified with the process whereby the interpretative structures of consciousness are created, rather than being identified with the structures themselves. The key to this sense of self-as-process lies in the reestablishment of a symbiosis or reciprocity between the dialectic modes of adaptation such that one both restricts and establishes the other, and such that each in its own separate sphere can reach its highest level of development by the activity of the other. Carl Rogers, in his description of the peak of human functioning, describes as well as anyone the process-centered nature of integrative consciousness:

There is a growing and continuing sense of acceptant ownership of these changing feelings, a basic trust in his own process. . . . Experiencing has lost almost completely its structure bound aspects and becomes process experiencing—that is, the situation is experienced and interpreted in its newness, not as the past. . . . The self becomes increasingly simply the subjective and reflexive awareness of experiencing. The self is much less frequently a perceived object, and much more frequently something confidently felt in process. . . . Personal constructs are tentatively reformulated, to be validated against further experience, but even then to be held loosely. . . . Internal communication is clear, with feelings and symbols well matched, and fresh terms for new feelings. There is the experiencing of effective choice of new ways of doing. [Rogers, 1961, pp. 151–52]

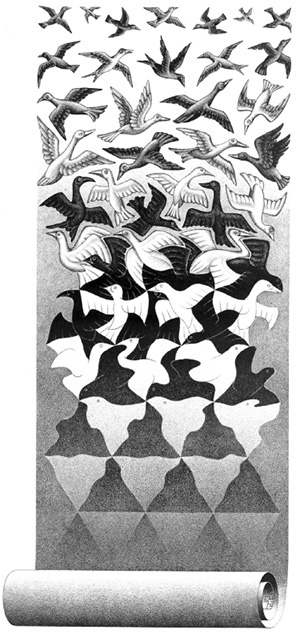

The development of integrative consciousness begins with the transcendence of one’s specialized interpretative consciousness and continues with, first, the exploration of the previously nonexpressed adaptive orientations and, later, the full acceptance of the dialectic relationship between the dominant and nondominant orientation. This embrace of the dialectic nature of experience leads to a self-identification with the process of learning. As can be seen in the description of the highest levels of hierarchic integration in the four learning modes (Figure 6.5), this process orientation is reflected in the incorporation of dialectic opposites in each of the modal descriptions. The integrative levels of affective complexity begin with the relativistic appreciation (in the fullest sense of the term) of value systems and conclude with an active value commitment in the context of that relativism (compare Perry, 1970). Integration in perceptual complexity begins with a similar relativistic appreciation of observational schemes and perspectives and concludes with intuition—the capacity for choosing meaningful perspectives and frameworks for interpreting experience. With integrative consciousness, symbolic complexity achieves first the ability to match creatively symbol systems and concrete objects and finally the capacity for finding and solving meaningful problems. Behavioral complexity at the integrative level begins with the development of an experimental, hypothesis-testing approach to action that introduces new tentativeness and flexibility to goal-oriented behavior—a tentativeness that is tempered in the final stage by the active commitment to responsible action in a world that can never be fully known because it is continually being created.

In his 1955 lithograph entitled “Liberation,” M. C. Escher captures the essence of the three developmental stages of experiential learning. The bottom third of the figure (Figure 6.5) shows the emergence of figures from an undifferentiated background, as in the acquisition stage of development. The middle third of the figure shows the articulation of form in tightly locked interaction between figure and ground, much as development in the specialization stage is achieved by finding one’s “niche” in society. The top of the figure shows the birds in free flight, emphasizing the process of flying over the content of their form, symbolizing the freedom and self-direction of integrative development.

Update and Reflections

I believe that when human beings are inwardly free to choose whatever they deeply value, they tend to value those objects, experiences and goals which make for their own survival, growth and development and development of others. . . . Instead of universal values “out there,” or a universal value system imposed by some group—philosophers, rulers, priests, or psychologists—we have the possibility of universal human value directions emerging from the experiencing of the human organism.

—Carl Rogers

The experiential learning theory of adult development described in Chapter 6 starts with the premise that development occurs through the process of learning from experience viewed as transactions between individual characteristics and external circumstances—between personal knowledge and social knowledge. Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development is outlined as an example of how these transactions integrate personal knowledge and social knowledge (see p. 198). Developmental progression in the theory is viewed as increasing differentiation and hierarchic integration of functioning, with the former preceding the latter in successive cycles of increasing integrative complexity. The Gestalt theorist Heinz Werner provides the basis for the multilinear experiential learning theory developmental model (Figure 6.3) which differentiates it from the Piaget-based unilinear models of adult development—e.g., Kohlberg, Perry, Kegan, and Loevinger. Unlike the Piagetian approaches, experiential learning theory considers individual differences in development, allows for the influence of culture and context, and recognizes development as multidimensional, encompassing affective, perceptual, and behavioral dimensions in addition to the exclusive Piagetian focus on cognitive development. Foregoing the detailed structural stages of the Piagetian models, development is broadly divided into three stages inspired by Jung—acquisition, specialization, and integration. The model then describes three levels of consciousness—registrative, interpretive, and integrative—and three levels of adaptation—performance, learning, and development—corresponding to the three stages respectively (Table 6.1). Since the publication of Experiential Learning, research has added support to the experiential learning theory development framework in some areas and suggested modifications in others. The update will review some of these insights.

Culture and Context

Piaget’s structural genetic epistemology was a bold effort to describe the child’s development toward the internalized logic of scientific rationality solely as an internal developmental process independent of culture and context. But unfortunately his reach exceeded his grasp. As much as his structuralism illuminated how the mind works, as Jerome Bruner notes, there is much his structural approach does not explain:

Even from within the Piagetian fold, the research of Kohlberg, Colby, and others point to the raggedness and irregularity of the so-called stages of moral development. Particularly, localness, context, historical opportunity, all play so large a role that it is embarrassing to have them outside Piaget’s system rather than within. But they cannot fit within. . . the system failed to capture the particularity of Everyman’s knowledge, the role of negotiations in establishing meaning, the tinkerer’s way of encapsulating knowledge rather than generalizing it, the muddle of ordinary moral judgment. As a system it. . . failed to yield a picture of self and of individuality. [Bruner, 1986, p. 147]

Vygotsky provided a strong counterpoint focusing as he did on the cultural tools, particularly language, and contexts that influence development; though still on a unilinear cognitive track. For Vygotsky language influenced thought giving new meanings and ideas, whereas for Piaget thought develops through its own internal, logic that is not determined by language; language is the medium for the expression of thought. For both men the relationship between thought and language is interactional, not transactional as is the enactivist learning spiral described in Chapter 2 Update and Reflections. Vygotsky’s famous example of how Marxist ideas improve the conceptual development of the mind and even his proximal zone of development where a more developed consciousness aids a lesser developed consciousness seem one-way and unilateral. Compare this with the transactional emergence of Gadamer’s (1965) conversation, which is larger than the consciousness of any player, or of Freire’s (1970) dialogue among equals.

Bruner argues that theories of development are more than descriptions of human growth; they acquire a normative influence that gives a social reality to the principles of the theory. He states, “. . . the truths of theories of development are relative to the cultural contexts in which they are applied. . . a question of congruence of values that prevail in the culture. It is this congruence that gives development theories—proposed initially as mere descriptions—a moral face once they have become embodied in the broader culture” (1986, p. 135). Barbara Rogoff (2003) gives a striking example in her research comparing educational practices in indigenous communities of the Americas with those of Western European heritage societies. In the Western societies children are organized by tight age grades and segregated from the mature activities of the community, spending their time in institutions such as schools where they are taught generalized abstract knowledge to prepare them for their later life in the society. This system is supported and justified by models of development based on reason and abstract universal knowledge from the Enlightenment to Piaget. In the indigenous communities children of all ages have wide access to community activities in which they will be expected to engage. They engage in direct learning from ongoing experience, through observation, collaboration, and ongoing support from others. Ethnographic studies of these communities suggest that children are more attentive and collaborative than Western middle-class children.

Individual Differences and Multilinear Development