1. How We Got Here and Where We Are Going

In the seven years since we published the first edition of this book, society has evolved significantly. Some of that evolution is a consequence of the continual integration of technology into our lives, and some a consequence of major geopolitical events. The two are intertwined. Although this book is not about societal evolution, we do intently explore one of the greatest forces at work for the advancement of free societies. We refer to this force as Retailing: The Trojan Horse of Global Freedom and Prosperity.1

In this chapter, we look at how retailing changed in the last century to accommodate and facilitate the growing prosperity and freedom of Western societies. We focus on how retailing, and retailers, must continue to evolve to meet the demands of newly prosperous societies around the globe as they apply new technologies that change how they shop for and acquire an ever-growing list of available products. We do not spend a lot of time prognosticating on the future. As Niels Bohr noted, “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.” This should not deter us, however, from noting obvious trajectories and preparing ourselves for the inevitable zigs and zags as society and retailing continue their pas de deux into an exciting and promising future.

We begin by defining selling in microdetail. I assume if you are reading this book that you are prepared for a series of deep discussions on various topics concerning the present state of retailing. The meaning of selling is perhaps the single most important of these topics. In this chapter, I offer my own paradigm for thinking about selling.

We examine how and why the self-service retail business, magnificent engine that it is, got to its current state. The foundations of modern self-service retail were laid 100 years ago. Without knowing something of the history, it is impossible to understand why things work the way they do today.

And finally, we look at how the science of selling, and basic economics, define the way online and offline retail, clicks and bricks, must converge into a single, even more efficient retail engine than either one alone could possibly achieve.

What Is Selling?

Think about the 360-degree view in the aisle of any self-service store in the world, as seen in Figure 1.1:

Figure 1.1 One shopper, thousands of items, yields only one, or a few, purchases. (Image by fStop Images—Patrick Strattner).

Now, ask yourself what the retailer wants to sell the shopper in that aisle? Think about it and you will realize the absurdity of the question. The retailer is not selling the shopper anything! The retailer cares very little about what the shopper buys. His function is not to sell any one thing; rather he is here to provide a wide range of products from which the shopper may select. The shoppers sell to themselves. This is how self-service retail evolved and nothing in its history would have caused the retailer to think about the actual sales process, with few exceptions.

Selling Requires a Salesperson, Not a Retailer

The selling that we refer to here is what automobile, life insurance, and real estate salespeople do. In these industries, professionals assist their clients in identifying and selecting the products that best meet their desires and needs while simultaneously working to move product and generate profit. This is true selling. Those in the business of selling study and celebrate their craft as an art and science. The general public has a poor understanding of the fine intricacies of this type of selling. Most retailers fall into this category as well. I am fortunate in having been indoctrinated very early in life in the principle that nothing happens until somebody sells something! You can learn more about personal selling from Joe Girard, who holds the Guinness World Record as the World’s Greatest Salesman, averaging more than two automobile sales per day over a 15-year period.2

Let’s return now to our shopper standing alone in an aisle surrounded by hundreds, possibly thousands, of products and trying to decide what she wants to buy. Bear in mind that if she buys anything in this aisle at all it will most likely be just one item. At most, she will purchase two or three items in this aisle. Half of the shoppers that walk down this aisle on any given day will buy five or fewer items from the entire store.

This is a hard fact that, fortunately for you, most of your competition absolutely refuses to believe. One retailer told me, “Our target demographic is the stock-up shopper.” In other words, he ignores half or more of his shoppers as non-target. The flaw in this common thinking is that a large number of those one-, two-, or three-item purchasers are stock-up shoppers. They simply are not on a stock-up trip on this occasion. Focusing on the efficiency of those small baskets is the key to substantial increases in the large baskets, too. (See Mike Twitty’s “The Quick Trip Paradox,” Chapter 7 of this book.)

The good news is that when you think about the challenge for the shopper and how you, as a good salesman and a ghost in the aisle,3 can assist her in deciding on what to purchase, it is not difficult to increase those small baskets. Do away with the fiction that what the retailer wants bears anything but a remote relation to what the shopper wants. The reason Joe Girard sold two automobiles a day, day after day, is that he obsessively focused on what the shopper wanted, not on what Joe himself might have wanted.

SELLING: Focus on the Big Head of What the Shopper Wants to Buy

We can begin to think this way in a self-service environment by thinking about the total shopping crowd. What does the crowd want? We can simply answer that—for the crowd—based on what they have already been buying. In relating to the individual shopper before us, we can use the crowd’s desires as a guide to satisfying the most individuals. Whatever the crowd wants in the greatest quantity means they have an itch for those products, which we will help them scratch. So our selling is first motivated by focusing only on items that are already appealing to lots of shoppers, generating lots of sales. This is the crowd component of our selling to shoppers. Leveraging the crowd component is illustrated in Figure 1.2a, where “Top” Seller refers to what “the crowd” has selected, not us.

The second component is to recognize that people mostly do not have the time or interest to do deep thinking about what they buy. Any little clue that will help them to quickly make a selection is genuinely useful to the shopper. Letting them know that this specific item is the one most people buy here is hugely helpful. Aha! So most people buy this, or “Choosy moms” buy this, or Connoisseurs prefer this one; these are powerful triggers. This then is the social component of our selling—creating an association with others the shopper is likely to respect or want to emulate. Hence, we refer to this as crowd-social marketing.

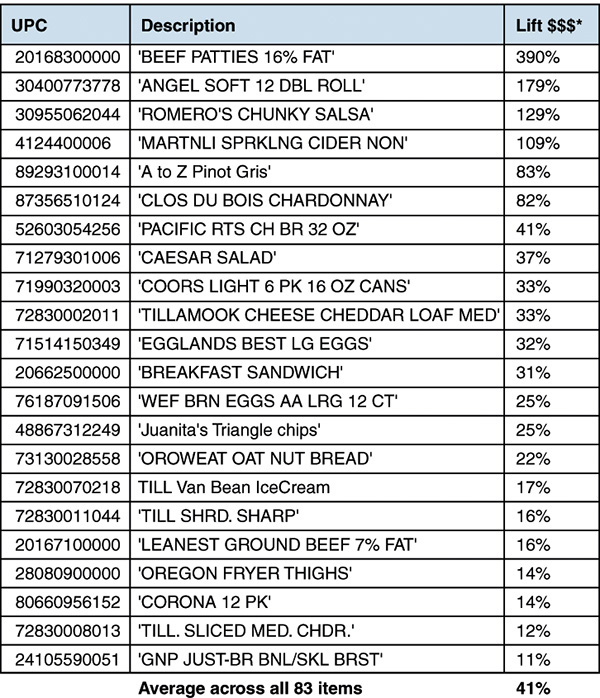

Figure 1.2a illustrates the way our crowd-social marketing, TopSeller technique, works in a store. In this case for Juanita’s Triangle Chips, the lift was actually 25% (see Figure 1.2b)!

Figure 1.2b The 83 items tagged Top Seller averaged 41% lift, year over year. This does not include the halo effect, due to more efficiency wherever the tag is used.

The full deployment of TopSeller tags in this store involved more than 80 carefully selected products, from those most purchased by shoppers, and resulted in an average sales increase of 41% across the featured items.

Note that we don’t expect for the shopper to necessarily notice this tag on the shelf on first sight. In fact, we don’t care if no one notices it. But the subconscious mind of shoppers who already are buying this product will note the tag and add it to their repertoire of subconscious triggers associated with that product. If they need some conscious help with this process, the text, “This item picked by our customers as one of Lamb’s bestselling products,” defers to “our customers,” who alone have made this a bestseller. This is what we refer to as “crowd-social” marketing with the shopper, although with a bit different context than is usual for these terms. In this case, we are leveraging the fact that most shoppers really do not have the time or interest to conduct a serious, rational evaluation of the products they buy. Stores provide all kinds of highly suspect cues, but the shopper is instinctively attracted to “The Wisdom of Crowds,”4 (See James Surowiecki.) So we are providing a gentle nudge to encourage the shopper to quickly drop in their basket something there is already a good probability that they were going to do.

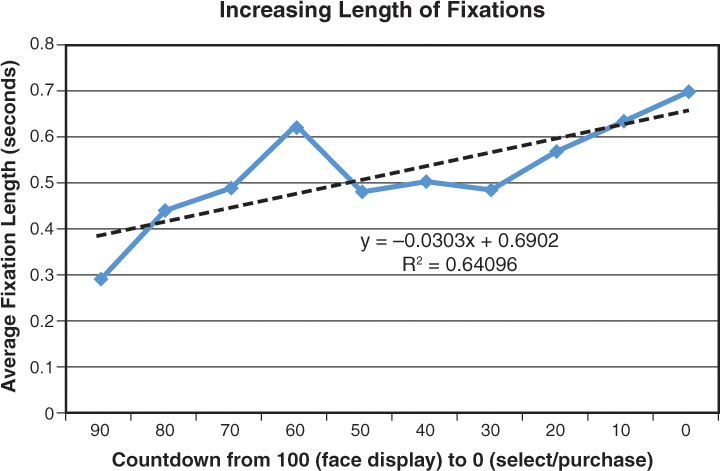

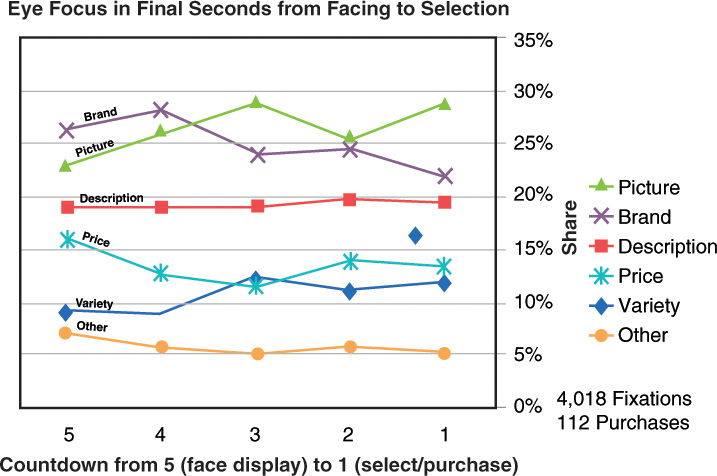

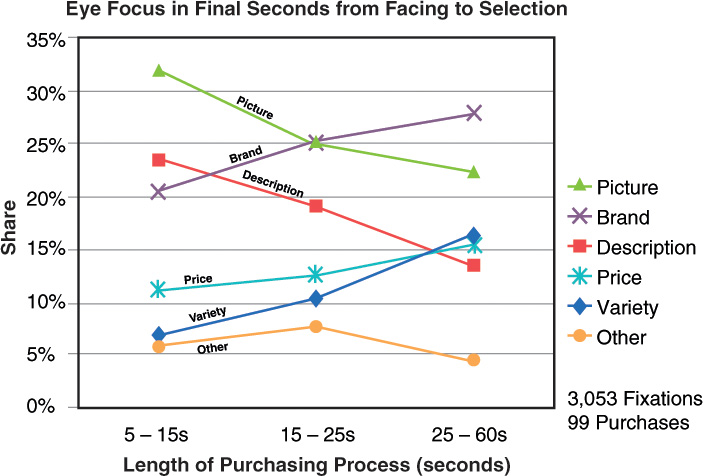

This brings us to the almost certain mechanism behind the increasing sales, even if our speculation about the subconscious is not totally correct. This is the relation between the speed of making the purchase, and the quantity of purchases made. From many careful measurements, we know that shoppers have some kind of internal clock, that must have a subconscious allocation of time for tasks in the store. So, for example, if we sell more quickly in a department, the shoppers do not leave until their “budgeted” time is up. Typically this leads to buying more of what they were buying, or of nearby products—increasing surrounding sales. This halo effect is of tremendous importance.

The general rule is that shoppers’ time is not elastic, but their money is. If you save them time, they will spend more money. If you impede their purchasing, they will do less of it.

An important thing to note is that the TopSeller program does not involve “paying the customer to buy,” also known as promotional pricing. We discuss this issue further in the navigational section of Chapter 2, (Tenet 3 describes the use of TopSeller to help move shoppers along the dominant path), but there is a wholesale, unwarranted expectation among retailers that splashing big signs proclaiming “price reductions” is the best way to “promote” anything. This is done while ignoring large amounts of data showing that it is not the price that drove increased sales, but the calling of attention to the product, often in a variety of ways. Promotion should never mean price alone, and in the majority of cases, price adds little to the value of the promotion.

Stop Shouting at Your Shoppers

The most powerful selling does not involve obnoxious, abrasive shouting at the customer. Far too many voices shout at shoppers in an effort to get their attention. This shouting is so pervasive in self-service stores that shoppers have developed what we call a clutter filter that operates at the subconscious level and discards the noise, leaving it unheard by the shopper. We encourage retailers to employ a more effective style of marketing that whispers to the shopper.5 This type of selling operates at the subconscious level, relying on the shopper’s instinctive responses. Most importantly, it does not try to get the shopper to buy anything they have no natural inclination to buy. It works with the shopper to help them do what their habits and instincts reveal they want to do. But there is also a stark difference in the time it takes to impact sales. This is a sure method whose impact builds over weeks and months. It is not a costly flash-in-the-pan, but a true nudge method whose effects compound over time.

The example of whispering shown below represents the tip of the iceberg of the potential increase in sales and profits that more efficient self-service retail can achieve through leveraging the shopper’s subconscious instincts. Figure 1.3 shows a photo of the shelf where our Top Seller tag whispered to shoppers on behalf of the “salesperson” and shows the impact of our technique:

The promoted item is nearly out-of-stock, or OOS, which is the best proof of extraordinary sales. We regularly see OOS with this nonfinancial promotion. What’s the solution to this problem that costs retailers 4 to 8% of sales across the board, other than more diligent stocking? You can double the display size for products that consistently go OOS. Never mind your deals with suppliers. This product has earned the love of the shoppers. The bricks store is a warehouse and allocation of storage, represented as shelf space, that should follow the needs of the shoppers as shown in the sales of merchandise.

How We Got This Way

No matter its incarnation, from the rickety, fetid, fish merchant’s stall in a dusty, cacophonous, medieval open-air market, to the sleek, computerized, Amazon drone that delivers a cellophane-encased DVD to your front door, retailing has always been about getting a product some people have produced into the hands of other people who want the product and are willing to pay for it. By studying how society has managed this process in the past, and how we developed the current system of self-service retail, we can better understand the evolution taking place now that’s driven by online retail and other advances in technology. The better we are able to see this bigger picture, the better we can position ourselves to thrive in the new retail landscape.

Here I look at the final mile of this process through a scientific lens and focus on the meeting of the minds of the retailer and shopper, the most critical function in retail, where the shopper agrees to purchase a specific product and the retailer agrees to provide the product for a specific price. From there, I work backwards through the mental process of the shopper to the origin of that need or desire. I also look at the process preceding the shopper’s trip to the store by which the retailers and suppliers play their part in making the products available, eventually leading us to the inside of the store and to that final transaction.

Early Shopping in America

One hundred years ago there were a half million small stores in America whose proprietors and clerks personally assisted each shopper in selecting the products they wished to purchase. Clerks often developed personal relationships with their customers and knew their preferences and dislikes. Clerks also had to have extensive knowledge of the products they made available in their shops. They knew which products they were most likely to sell to which shoppers. Products were usually displayed on shelves behind the counter and out of reach of the shoppers who relied on the clerks to guide them in their purchasing decisions by narrowing the selection and dismissing any products that would not meet their needs or desires. The clerk eventually passed selected products across the counter to the shopper for closer inspection or for purchase. In this way, clerks sold products to shoppers.

The Birth of Self-Service Retail

In the early twentieth century, increased production, efficient supply and distribution chains, and lower prices for most products expanded the store shelves tremendously. To accommodate this massive increase in available products, the clerk was replaced by the merchant warehouseman who arranged products on shelves accessible to the shoppers. This model continues today, as shoppers navigate aisles filled with unprecedented amounts of inventory, ever-increasing variety at ever-decreasing prices. Instead of helpful clerks providing individualized assistance, a cacophony of voices in the forms of labeling, advertising, and promotions assault shoppers from all sides. Shoppers must rely on the products themselves for assistance in determining which best meet their needs or desires. Their interactions with the merchant are reduced to a brief transaction at the check-out stand.

The massive increase in productivity brought about by the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent transformation of society drove the transition from service retail to self-service retail. Several important players had a hand this process, but one dominated the field of retail in the early twentieth century. The impact on retail of The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, better known as A&P, was outsized, and A&P ultimately became the first billion-dollar retailer in the world.6

A&P began as a tea merchant in the nineteenth century. In 1870, many years before the self-service retail revolution, the company introduced the first consumer packaged good, although at the time they only sold it to the wholesale trade (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Thea Nectar, packaged tea introduced in 1870 by the Great A&P. Advertisement © Great Atlantic & Pacific.

Think of that package of tea as the harbinger of the explosive growth of branded, packaged goods 50 years later. Branding and prepackaging products was a prerequisite for the efficient distribution and selling of products by self-service retail. The efficiency of mass production and mass packaging demanded efficiency in distribution and retailing, both of which were seriously fragmented and inefficient in the early years of the twentieth century.

At this point, the two Hartford brothers, John and George, heirs to the A&P tea business, began what would eventually become the world’s first billion-dollar retail business. John was the marketing genius who could presage the movement of society and read the evolving market like a book. George was a number cruncher, running a data-driven business with paper, pencil, and mimeograph long before electronic calculators or computers.

Together, the Hartford brothers built a business model that would influence self-service retail for the next 100 years. Their revolutionary strategy did not rely on return on margins, the basic foundation of most businesses. Instead, they built on return on capital. This was a huge issue, the misunderstanding of which leads to a lot of misunderstanding of retailing today, even by many within the industry. As Marc Levinson explains:

The preference for volume over margin was a matter on which the Hartford brothers [initially] did not see eye to eye. George hewed to a traditional understanding of retail profitability, preferring to maintain a generous markup on each item sold. Profits averaged an impressive 3% of sales from 1921 to 1925, appearing to show the success of the high-markup strategy. John, though, downplayed return on sales as a measure of profitability. He preferred to watch the company’s return on investment. Historically, A&P’s pretax return on investment had exceeded 25% in most years, and John set that as the norm. The way to boost return on investment, he thought, was to make better use of capital by pushing more merchandise through A&P’s stores and warehouses.

Rather than trying to increase profits per dollar of sales—the conventional strategy of the day—A&P was deliberately seeking to reduce profits per dollar sold in hopes of creating more sales.

The two brothers’ strengths were in unique alignment. John Hartford’s high-volume, low-price strategy, executed with George Hartford scrutinizing every financial detail, represented a radically new model for retailers.

This business of measuring profitability based on revenue per capital deployed rather than revenue per margins (on dollar sales) is at the heart of driving prices down, down, down while driving volume up, up, up. Think about this in relation to Amazon nearly a century later. Capital efficiency is driving the next wave of retailing—not the mode of selling or delivery.

This business model was made to order for a self-service retailer, who stocked the warehouse (store) and used unpaid stock-pickers (shoppers) to sell themselves the merchandise they wanted with the retailer collecting payment at the exit. The retailer turned merchant warehouseman. This was efficiency!

A&P drove that efficiency as their volume increased across large numbers of stores. They expected their suppliers to be more efficient, too. Where they could not find suitably efficient suppliers, A&P built their own plants and manufactured their own products. Kroger was another retailer active in manufacturing. The same principle applied to the distribution and warehousing aspects of the business. No one who continued to do retailing according to nineteenth-century paradigms was spared under the new, more efficient system introduced by chains like A&P. The slaughter was complete from the mom and pop stores, up the chain through the distributors, wholesalers, and to the manufacturers themselves. Joseph Schumpeter described the process as creative destruction. We are experiencing another wave of creative destruction today.

Today, we take for granted many of the features created as a part of the self-service retail evolution. We fail to recognize how and why they came into being, and possibly more importantly, how they interrelate. Really low prices came from not trying to make profits based on margin sales, but instead on super-efficiency of the capital investment. This meant that the return on capital was high with prices being low, driving traffic of both shoppers and products through the stores.

But there is another source of income for a retailer like A&P. The company advertised and promoted the merchandise in their stores in weekly circulars and newspapers. Brand suppliers realized the tremendous benefit in getting their own products featured in A&P’s print advertising. And A&P expected their brand suppliers to help pay for that advertising. But think about this: If the brands were paying to promote their own products through A&P advertising, why shouldn’t A&P also charge the brand for various other promotional services inside the store?

Remember, A&P was aiming for as close to zero mark-up on products as they possibly could, to keep prices low and drive traffic through the stores. At the same time, the brands were aiming for—and achieving—relatively high margins. So why shouldn’t the retailer who was stocking and delivering those products to the customer share in some of that brand margin as a reasonable share of advertising money?

As well as becoming merchant warehousemen 100 years ago, in the same process, retailers also became major media companies. Stores offered a way for a brand manufacturer to reach his audience. Stores could sell the access to their shoppers in the same way that a newspaper sold advertising on the basis of their circulation.

The evolution of self-service retailers into media companies selling access to an audience was a direct consequence of merchant warehousemen choosing not to make the majority of their profits by marking up the prices of the products, but rather by getting as close as they could to giving away products in order to generate massive traffic. To John Hartford, this amounted to 2.5% net profit from selling products to shoppers, an absurdly low level if this was their only revenue. But this was a media company now.

This arrangement—merchant warehousemen providing brand suppliers with access to large numbers of shoppers in exchange for financial consideration from those suppliers, while offering products at low prices to the shoppers—has not changed in the past 100 years. Not really, of course. But self-service retailers still operate in the paradigm that A&P created. A decade after the Hartford brothers died, a new player, adopting a modified form of the Hartford plan, broke on the scene—Sam Walton.

Although Walton pursued the same ferocious low price strategy that the Hartford brothers had, he did not follow their model of selling his suppliers access to his shoppers. He expected suppliers to give him all that media money in the form of lower wholesale prices. He would promote Walmart stores and the products he sold without direct supplier participation. Suppliers could only buy favor with Walmart by cutting their own prices.

Although we cannot fully understand self-service retail without understanding the advertising component of the business, we must also consider that for the brand suppliers, retailer advertising was only one component of the reach business. The need of suppliers to reach the self-service retail shoppers had a significant impact on the development of radio and television. Major brand sponsorship of programming such as soap operas, sporting events, and news funded the rapid growth of those media. Figure 1.8 illustrates the classic Tide advertisement.

The selling by major brands through mass media represented an efficient means of communicating with their customers. But through the programing it made possible, and even through the commercials themselves, it also helped knit disparate regions of the country into a unified whole and created a new national consciousness. Retailing may have been an unwitting and unintentional force behind this transformation, but that does not alter the fact that retailing has been at the cutting edge of social evolution for the past century. In a sense, efficiency and convenience are the glue that binds the United States together. And, the glue of commerce will work its will on the global population regardless of political forces to the contrary.

Can Selling Make a Comeback in the Twenty-first Century?

By the second half of the twentieth century, the selling that was once practiced in small retail stores across the country was now ensconced in the national media and driven by the troika: brand manufacturers, advertising agencies, and major broadcast networks. But any professional salesman lives for the final moment of the sale, in the close, when the sale is consummated! Hence the mantra, “close early and close often.” Unfortunately, it is not possible for even the most super-selling mass media to actually close the sale for the self-service retail shopper, because they cannot be in the aisle where the sale is ultimately consummated.

We began our discussion of the consummation of the sale by explaining why no one is actually selling to shoppers in self-service stores and how shoppers must actually sell to themselves with little assistance from retailers or suppliers. We demonstrated one remedy for this situation with the example of using Top Seller tags allowing the retailer to be a ghost in the aisle and actually sell a product by tapping the habits of current buyers. We now look at the next evolution self-service retailing must make in order to remain the effective force for global freedom and prosperity it has been for the past century.

First, let’s begin with the reasonable assumption that we are going exactly where we are already heading. For this purpose, we will divide all the purchases made by all the shoppers in all the stores in the world, regardless of product category or class of trade, into four general categories. This is necessary because most of my facts and figures and my science of retail is driven by the study of high-volume self-service retail. However, the principles can be applied broadly. But they are easier to apply if we recognize the classes of purchases made in any store. These principles can guide your thinking in any store in the world. (See Chapter 6, “Long Cycle Purchasing.”)

The Four Dimensions of Purchasing

Before we examine how to sell in a self-service store, we need to better understand the shoppers and how the absence of selling manifests to them. We also need to understand the shopper’s online selling experiences and how those experiences translate to the bricks world. We can think of the shopper’s experience, both online and bricks, in terms of a hedonic-time dimension. A hedonic dimension, one driven by elements such as enjoyment, convenience, and pleasure, alone is inadequate for our purpose because time is often the most important element to the shopper.

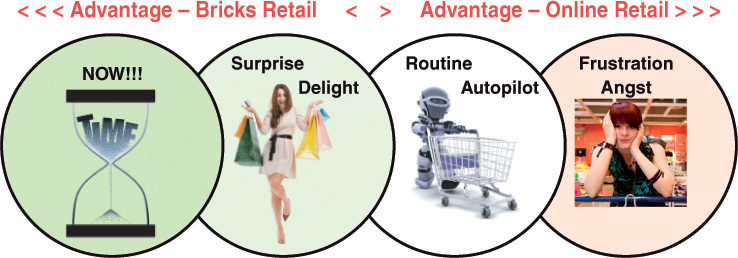

We can express the Hedonic-Time Dimension in four purchase states: Now!, Surprise/Delight, Routine/Autopilot, and Frustration/Angst (Figure 1.9). These four states have parallels in the personal sales world. Think of self-service as unmediated selling, and personal sales as mediated selling. If you have a personal sales store, you simply have that personal layer over the underlying self-service structure I am describing.

Figure 1.9 The four purchase states: 1-Immediacy (Now!); 2-Pleasure (Surprise/Delight); 3-Routine (Autopilot); 4-Frustration (Angst). (In order from left to right: © bokasana / Fotolia, © puhhha / Fotolia, © Kirsty Pargeter / Fotolia, © Dieter Hawlan / Fotolia).

Because the four purchase states describe the psychic state of the shopper and say nothing about the class of merchandise they are shopping for and purchasing, this paradigm works for retailing “shoes or ships or sealing wax” as Lewis Carroll might have described it. It transcends all self-service retail, whether supermarkets, electronic stores, clothing, auto parts or any other class of trade.

These four purchase states are a key to understanding how bricks retailing is currently intersecting with online retailing. As we define these states and map out an ideal path for bricks retailers and online retailers, a paradigm emerges in which the two converge rather than merely intersect.

Now! Purchases (Advantage—Bricks Retail)

From the traditional trade in early development markets to the most advanced markets in the world, stores have always functioned as communal pantries, a place where everyone in the community can go to get things that they do not presently have in stock in their own homes or workplaces. There is a stage in our evolution from the minimalist living of primitives when growing wealth allows the population to begin storing excess provisions of all types in their own homes. This storing of excess, for later use, is done in the pantry. Later, when abundance becomes more common, and stores more ubiquitous, it makes a lot less sense to store things in either home or office, and then society moves back in the direction of the communal pantry in which the store stores everything you need, and you simply come and get it.

We do not readily recognize that we live in such a system, because when we ask shoppers how many items they purchased at the store on their most recent trip, no one says “one” and most say “five” or even more. But as we will see, studies show that the most common number of items purchased from any store in the world is one. We won’t provide a full psychological explanation for this fact, but usually shoppers do not buy a single item in a store for use the next day, week, or month. Single items are purchased to fill an immediate need. Immediacy drives the single-item purchase, which is inextricably then linked to Now!

The Now! factor heavily favors bricks retailing. Hence, the large focus of online retailing on same-day or next-day delivery. But, for genuine immediacy, other than electronic delivery of music, books, and the like, it is hard to see how bricks retailing can totally lose their immediacy advantage.

Surprise/Delight Purchases (Advantage—Bricks Retail)

You might think of Surprise/Delight as the domain of clothing, electronics, sports gear, or other non-grocery type merchandise. But we can reasonably apply the classification to a large range of merchandise. Often, retailers single-mindedly focus on price for this function. That can obviously be costly. Other experiential factors, however, can play a role here. For example, something as simple as quality customer service might be a Surprise/Delight.

There is a 360-degree experience attendant on bricks shopping that strongly supports Surprise/Delight. But the most common bricks retailer experience, in which shoppers navigate through rows and aisles filled with tens of thousands of items, is not impenetrable to online. This means that even though bricks has some inherent advantages for this purchase state, the typical bricks store is highly vulnerable to online Surprise/Delight challenges.

Routine/Autopilot Purchases (Advantage—Online Retail)

This state refers to what Neale Martin7 describes as anything the shopper habitually buys, whether by frequency or by a consistent pattern of behavior. Anything purchased routinely can be automated or semi-automated, at tremendous relief to the shopper, making all such purchases the natural bailiwick of the online retailer.

This category of merchandising is heavily weighted toward groceries. Remember, groceries drove Walmart to nearly half a trillion dollars in sales. People did not spend all that money on groceries, but the frequency of their trips to buy groceries drove a lot of other purchases. The efficiency with which online retailers can tap into the Routine/Autopilot purchase represents the bricks retailer’s greatest vulnerability.

Frustration/Angst Purchases (Advantage—Online Retail)

The frustration and angst purchases are often phantom purchases, meaning that they don’t happen, even though the shopper wants them to happen. Have you been to a store recently and left without something you really wanted or needed but couldn’t find? Maybe you couldn’t find the right color, flavor, or size. Maybe the store didn’t have anything close to what you wanted. Or possibly it was a price issue. That’s a phantom purchase, a purchase that never happened!

These purchases will never go away. But Amazon, with its Everything Store strategy, backed up by a host of other online merchants a Google search away, means online will own the Frustration/Angst purchase. This doesn’t mean that bricks will not continue to play a part. Remember, immediate need favors the bricks retailer in nearly all cases.

Where Is Selling Going?

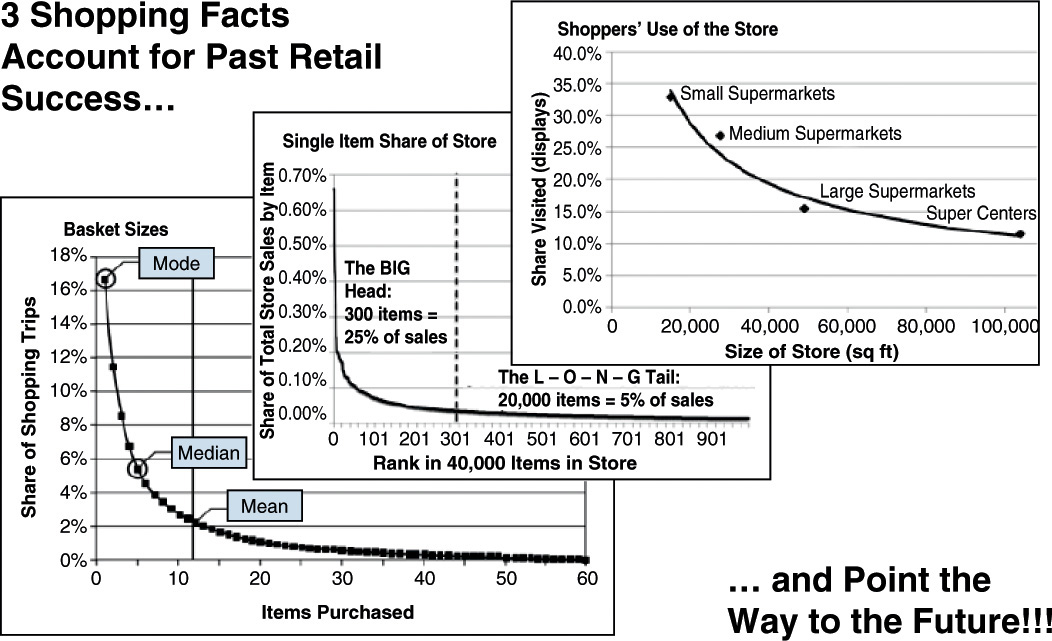

So with these purchase psychology principles in mind, let’s get into the pivotal facts that are driving retail where many do not want to go. There are three basic sets of data that tell the tale, Figure 1.10:

The first chart (at the lower left) shows just how many items shoppers buy in the store. This curve looks the same for any store in the world, except that the scale on the bottom varies depending on the type of store. The one here shows a supermarket, but a drug store or a supercenter would have the same curve shape. Just the median moves, with smaller medians for smaller stores and larger medians for larger stores. This chart tells us a lot about current retail and where it is going. The rule here is that the largest number of trips buys very little. This is definitely driven by the Now! type purchase.

The second chart (in the middle) describes the Big Head. This represents what is bought in large quantity. Shoppers across the spectrum share a lot of characteristics: Most everyone buys milk, eggs, butter, bread, and so on. This leads the crowd of shoppers to buy certain products in large quantity; hence, Big Head. On the other hand, everyone is unique in some ways and they buy distinctive items for themselves. Some of us like macadamia nuts and others prefer cashews. Or very few shoppers buy many items rarely and others not at all. This creates the Long Tail. Nearly all bricks retailers do a poor job of distinctly managing these two entities. This spells large opportunity for those who choose to do it right. Hint: Some of the most successful stores in the world have just lopped off the Long Tail. Costco, the second largest retailer globally, has only 4,000 items in the store. However, I have long believed that any Big Head plus Long Tail store could outperform a Big Head only store. Amazon is certainly proving this online.

The third chart (at the upper-right) reflects the retailers’ poor management of the Big Head and the Long Tail by showing the larger the store, the less of it is visited by shoppers. Although shoppers do tend to buy more items per trip in larger stores, the overall efficiency of the store plummets. Nearly all bricks stores are squandering two types of capital: real estate, such as buildings and fixtures, and static inventory. The larger the store, the more capital it squanders. I refer to this capital as parked, because it is very inefficient in delivering sales.

Online retailing addresses the parked capital problem. Amazon does not have unpaid stock-pickers wasting warehouse space along with unmoving inventory. Notice they do pay their stock-pickers, which is an online disadvantage to bricks, where they are unpaid.

Given the natural advantages of bricks retailers for one share of purchase states and a natural advantage of online for a different share of purchase states, any serious retailer must manage both modes under their banner. The problem is that skilled retailers like Amazon are essentially mediating sales to shoppers automatically but in a personal sales mode. Their selling strategies tap into the intuitive, instinctive, and habitual tendencies of shoppers and rival the mediated personal sales occurring in the service-type bricks store. The challenge lying ahead is to figure out how bricks retailing can be more efficient and at the same time supercharge that efficiency by a blended online presence within the bricks store. We take a closer look at how retail is struggling with this challenge in our chapter on Amazon’s bricks store in Seattle.

While bricks retailers are struggling, often in ineffective ways, to bring online to their bricks stores through click and collect, where shoppers order products online then pick-up their orders at the store, Amazon is moving to become an overt bricks retailer.8 Any bricks retailers looking to thrive through the next evolution in self-service retail will adopt an approach complementary to the one in those Amazon stores. That is, bricks retailers must be looking to encroach on Amazon’s business, from within their bricks stores!

We will now consider in some detail a phased plan for converting a bricks store into a store that retains its brand but with the retail potential of the pending Amazon bricks stores.

Like the early twentieth-century mom and pop store that fell to the relentless efficiency of retailers like A&P, unless today’s bricks store learns to un-park its capital and improves shopper efficiency it is a sitting duck for the predatory intentions of Amazon. Successful online retailers such as Amazon will learn the basics of Big Head bricks retailing much easier than successful bricks retailers can learn to meet the minds of their shoppers, because of their long-learned merchant warehousemen ways. By applying its automated personal selling process, without the wasteful capital, Amazon could become the world’s largest retailer in just a few years.

The Selling Prescription

As successful as online retailing has been to this point, online is not going to swallow up the entire world of retail. I like to say that as long as people live in bricks houses, they will be shopping in bricks stores. Eventually, however, online and bricks must converge in an ideal store that leverages the strengths of both modes and taps into all four purchasing states. Anyone who can successfully manage that evolution will own retail in the twenty-first century.

I have great confidence that someone will actually build and operate many thousands of these ideal stores. But they will not be cookie-cutter stores. Populations and markets have great similarities which we want to leverage. But they also have differences, which is what drives the Long Tail. So our prescription will have some rigid and invariant principles, but also lots of flexibility, both in final execution and in getting from where each store is to the varied form of ideal that will be its evolving future.

If we could even semi-automate half of the routine/autopilot grocery purchases made in stores, we could drastically reduce the square footage of selling space needed while massively increasing shopper efficiency. At the same time, we could turn our attention to the Surprise/Delight function. For starters, let’s just focus on the shopper’s efficiency.

The Shopper’s Ideal Self-Service Retail Experience

A convergence between bricks and online might work like this: At the beginning of each week, the retailer sends every shopper enrolled in the program a list of items they most likely need to buy this week based on their prior purchases and the seasonal calendar. Think of this list as their “stock-picking” list. The shopper can strike off what items they do not want and add anything they do want that is not already on the list. The majority of any soft upselling should be done in the retailer’s creation of the list itself. Then the shopper return-emails the list to the store. The bricks retailer confirms the order in the same way Amazon does, including the time for pick-up.

Quite a number of bricks retailers are already facilitating shoppers ordering from the store using the Internet. The shopper simply comes to the store to pick up their order. There should be no special attempt to get them to order everything, especially fresh produce and other products that are an important component of Surprise/Delight.

If you intend to continue to be a bricks retailer, you should not encourage shipping. The reason for this will become clear in the following process. The orders themselves are stock-picked by low-wage employees during slow times in the store, prepackaged in clear plastic bags so the shopper can see what they are getting, charged to the shopper, placed in a shopping cart with the shopper’s name and list prominently affixed, and held in a secure area near the entry of the store but well within the shopping area. We will call this pick-up area the convergence depot. This crucial step is potentially as important as Amazon’s one-click ordering. The goal is to encourage the shopper to put additional items in the basket and add them to the checkout total when they come to the store for pick-up. If curbside delivery is offered, the delivery staff should always offer appropriate add-on items. Remember: never stop selling, Ms. Active Retailer!

We do not want to hurry the shopper away from the store. Rather, we are accelerating the Routine/Autopilot purchases through the online mode. At the same time, we do not want to obstruct shoppers from leaving immediately, recognizing the time factor of the hedonic-time dimension in which the four purchasing states exist. This is the essential element of the convergence of online and bricks retailing. Bricks retailers must not think of themselves as running bricks stores with the alternative of shopping at their online store. It must be one smoothly integrated operation, and the simple process described here will facilitate the convergence by taking the drudgery of routine purchasing off the table, allowing what time is devoted to bricks shopping to be diverted to Surprise/Delight and Now! shopping.

What Does the Ideal Self-Service Retail Store of the Future Look Like?

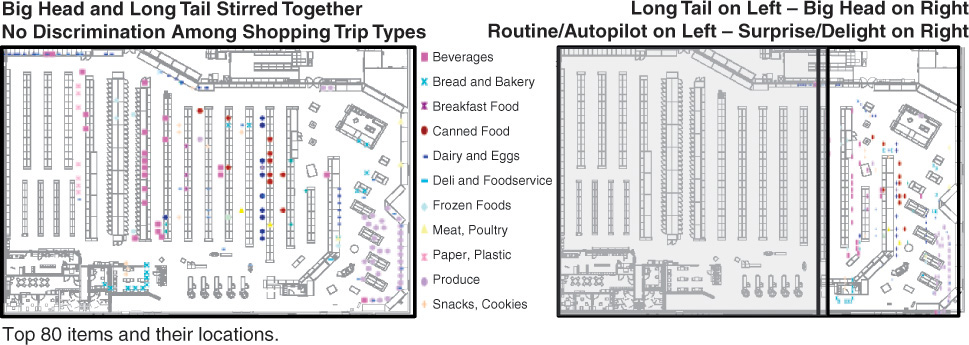

To show how our ideal store is divided into two separate functions, consider this diagram, Figure 1.11:

The store on the left is an actual supermarket, and the dots show the locations of 80 of the top 500 sellers, to illustrate dispersion across the store. Those dots represent the named categories, starting with the number-one seller (bananas). The top 500 altogether represent about one third of total store sales. The store on the left has dispersed the items that are most important to the shoppers across the entire store. The store on the right concentrates those items in a smaller area about one-third the size, which is devoted to efficiently serving the shopping crowd. This store is targeting the Surprise/Delight/Now! shopper.

What we are doing here is moving every one of those individual items into the one-third of the store nearest the entrance and leaving the Long Tail in a new “warehouse” area. This doesn’t mean there is a hard and fast rule that no Big Head items can be in the Long Tail area, or that no Long Tail items can occur in the Big Head area. Secondary placements will make sense on a very selective basis. But let me point out that one of the major reasons produce outsells every other category in the store is simply because the total number of items on display in this relatively large area is miniscule compared to what is typical of center-of-store aisles. I’m not detracting from the value of fresh fruit and vegetables but simply pointing out that the way they are merchandised has a lot to do with their very large sales. And this is why Big Head stores around the world vastly outperform the typical Long Tail store—95% of the stores in the world.

What we have done here is create a means for distinct management of the Routine/Autopilot sale, those sales that need to move to online ordering and ultimately to automated, or even robotic, stock-picking. This is the path to radically downsizing the parked capital in store area and inventory. Do not hesitate in testing the waters by restructuring your merchandise to align with this plan. Remember, though, this is an evolutionary process in which the shopper must take the lead by ordering their Routine/Autopilot purchases online. They are going to do it with Amazon, or someone else, if not with you.

The Dark Store

Bear in mind that retailers in the United Kingdom and France have already significantly leveraged the dark store concept, in which the store shelves are not open to the public but rather house goods to fulfill online orders. In Europe, the dark store primarily facilitates click and collect.9 These examples bear little relation to the convergence of online, mobile, and bricks-and-mortar (COMB) retail that we examine here. In the U.S., the Toys-R-Us dark store effort uses existing stores as warehouses, struggling blindly to make some use of their parked inventory in an online mode.10 Retailers need to realize that a large portion of their store is already dark in the sense that shoppers make very little use of it.

What we prescribe here is the gradual evolution to a store that does not need such a large dark store component, but allows that function to be shared across large numbers of their former Big Head and Long Tail stores (refer to the left illustration in Figure 1.11). We want to build a very large volume of online sales by nudging shoppers to replace the shopping they normally do in in the dark portions of the supermarkets they already frequent with online shopping. Don’t shove them out of your dark store. Just make it more convenient for them to buy the dark store products from you online while they continue to buy Surprise/Delight/Now! purchases in your smaller, more efficient, higher velocity, store. And, they often begin those purchases when they pick up their shopping carts prefilled with their online orders, with their name on it, in your convergence depot!

Step-by-Step

Next we outline the probable phases in moving from current self-service retail store to a store that leverages the Surprise/Delight/Now! purchase states while reducing the parked capital of the dark and Long Tail store (refer to the right and left side of Figure 1.11).

![]() Phase I—Existing store with significant online fulfillment: Quite a few stores—particularly in the UK, but around the globe, already have the option to order online and pick-up at the store, or click and collect. As a retailer managing your store’s evolution into a fully converged online and bricks store, your first step is to begin the process by adding the convergence depot near the front of the store but within the current first shopping area, that is, wherever most shoppers now actually begin selecting items for purchase, often the produce area. The convergence depot should be attractive and highly visible so that all shoppers in the store can see how online shoppers benefit from preordering their purchases by having the orders ready for them when they arrive at the store. But also so they can watch these shoppers possibly picking up a few more items to add to those carts with an express checkout just for the preorder customers. Keep in mind that payment systems will continue integrating near field communication and other technologies that will eventually eliminate check-out as we know it. Retailers will need to keep up with these developments while at the same time implementing the necessary changes to leverage them.

Phase I—Existing store with significant online fulfillment: Quite a few stores—particularly in the UK, but around the globe, already have the option to order online and pick-up at the store, or click and collect. As a retailer managing your store’s evolution into a fully converged online and bricks store, your first step is to begin the process by adding the convergence depot near the front of the store but within the current first shopping area, that is, wherever most shoppers now actually begin selecting items for purchase, often the produce area. The convergence depot should be attractive and highly visible so that all shoppers in the store can see how online shoppers benefit from preordering their purchases by having the orders ready for them when they arrive at the store. But also so they can watch these shoppers possibly picking up a few more items to add to those carts with an express checkout just for the preorder customers. Keep in mind that payment systems will continue integrating near field communication and other technologies that will eventually eliminate check-out as we know it. Retailers will need to keep up with these developments while at the same time implementing the necessary changes to leverage them.

![]() Phase II—Bidirectional migration of Big Head and Long Tail merchandise: Notice that there is no need to shuffle merchandise while you are building your online base of shoppers, who are also smoothly transitioning from online to bricks when they pick up at the store. As this process builds, closely monitor what additional items shoppers are buying in the store along with their online orders as a guide to decide what products would be best moved from the dark, Long Tail store to your budding Surprise/Delight/Now! store. At the same time, anything crowding the Surprise/Delight/Now! store but moving slowly is parked merchandise and should be targeted for migrating to the dark, Long Tail section of your store. These movements can begin early and should be driven by close monitoring of the transaction logs.

Phase II—Bidirectional migration of Big Head and Long Tail merchandise: Notice that there is no need to shuffle merchandise while you are building your online base of shoppers, who are also smoothly transitioning from online to bricks when they pick up at the store. As this process builds, closely monitor what additional items shoppers are buying in the store along with their online orders as a guide to decide what products would be best moved from the dark, Long Tail store to your budding Surprise/Delight/Now! store. At the same time, anything crowding the Surprise/Delight/Now! store but moving slowly is parked merchandise and should be targeted for migrating to the dark, Long Tail section of your store. These movements can begin early and should be driven by close monitoring of the transaction logs.

![]() Phase III—Making the Surprise/Delight/Now!–Dark/Long Tail distinction explicit to the shoppers: At some point, you will have enough volume from online sales coming out of the store that you will be able to pool online orders from multiple stores. For example, the shoppers picking up their online ordered merchandise from your convergence depot really don’t care where that merchandise came from. You may use the dark, Long Tail section of a single store to service a group of maybe 10 or more stores. Phase III tees up the ball for that move by perhaps distinctly partitioning all dark, Long Tail sections in the individual stores and eventually selecting one of the stores to be the dark, Long Tail mothership for all the others. This is also the phase in which to semifinalize just what the composition of the Surprise/Delight/Now! is going to be, probably no more than a few thousand SKUs.

Phase III—Making the Surprise/Delight/Now!–Dark/Long Tail distinction explicit to the shoppers: At some point, you will have enough volume from online sales coming out of the store that you will be able to pool online orders from multiple stores. For example, the shoppers picking up their online ordered merchandise from your convergence depot really don’t care where that merchandise came from. You may use the dark, Long Tail section of a single store to service a group of maybe 10 or more stores. Phase III tees up the ball for that move by perhaps distinctly partitioning all dark, Long Tail sections in the individual stores and eventually selecting one of the stores to be the dark, Long Tail mothership for all the others. This is also the phase in which to semifinalize just what the composition of the Surprise/Delight/Now! is going to be, probably no more than a few thousand SKUs.

![]() Phase IV—Nearly all stores are only Surprise/Delight/Now! with dark stores abandoned or repurposed: The final, ideal neighborhood store will be around 10,000 square feet with a heavy focus on fresh deli, bakery, produce, and high volume purchases. Shoppers select most of their purchases before leaving their home, nudged by whispers from the ghost in the cloud, the twenty-first century version of the helpful clerk reminding them what products they might need and which products they might desire. They arrive at the store to find their shopping cart waiting for them in the welcoming convergence depot already stocked with all their Routine/Autopilot purchases. Rather than tediously meandering up and down aisles of shelves stocked with thousands of products, immediately upon entering the store shoppers encounter a plethora of Surprise/Delight purchasing opportunities. They browse through pleasantly arranged selections of high-volume, low-priced products that make them want to buy for the joy of it! Perhaps they decide to indulge in a treat tonight and wander through the bakery or look in the ice cream display to satisfy that Now! impulse. After adding several products to their cart, they head to the express checkout.

Phase IV—Nearly all stores are only Surprise/Delight/Now! with dark stores abandoned or repurposed: The final, ideal neighborhood store will be around 10,000 square feet with a heavy focus on fresh deli, bakery, produce, and high volume purchases. Shoppers select most of their purchases before leaving their home, nudged by whispers from the ghost in the cloud, the twenty-first century version of the helpful clerk reminding them what products they might need and which products they might desire. They arrive at the store to find their shopping cart waiting for them in the welcoming convergence depot already stocked with all their Routine/Autopilot purchases. Rather than tediously meandering up and down aisles of shelves stocked with thousands of products, immediately upon entering the store shoppers encounter a plethora of Surprise/Delight purchasing opportunities. They browse through pleasantly arranged selections of high-volume, low-priced products that make them want to buy for the joy of it! Perhaps they decide to indulge in a treat tonight and wander through the bakery or look in the ice cream display to satisfy that Now! impulse. After adding several products to their cart, they head to the express checkout.

It is possible that many of these new communal pantries will be built by new players in the self-service retail game, perhaps Amazon, Google, or other aggressive global players that successfully mastered the convergence of online and bricks retail.

Something like this four-phase process must almost certainly happen, given global retail trends today. A huge driving force will be the shoppers who will love the convenience—and probably savings. For the retailer reducing the untenable amount of capital currently parked in inefficient space and inventory, this will level the playing field against pure online retailers as well as the traditional bricks competition.

The Ever-Changing Retail Landscape Favors an Evolving Retailer Species

We have examined how at the beginning of the last century retail changed from a personal sales model to a merchant warehouse model to accommodate and facilitate the growing prosperity of Western societies. That revolution saw the slaughter of small, inefficient stores unable to compete with advances in supply chain management, large merchant warehouse stores, and resulting lower prices. We have also shown that at the beginning of the twenty-first century we are experiencing yet another retail revolution as shoppers adopt new technologies that offer even more efficient ways to shop for and acquire the products they need and desire. And we have mapped out a possible strategy for retailers willing and ready to join the revolution and fully exploit the potential of a new selling paradigm that leverages the convergence of online, mobile, and bricks retailing (COMB).

Change is never easy. Many retailers have not yet gone beyond the tentative first phases of adopting a new model for selling. Others are struggling for survival, blaming a global economy for decimating their businesses while failing to recognize a fundamental shift in the very functions of buying and selling. But this revolution is just getting underway. In the years to come, it will drive us to new heights of efficiency beyond anything Joseph Schumpeter could have imagined when he described the last century’s revolution as creative destruction.

Our next chapter provides a set of five vital tenets as a suite of metrics that will define those retailers surviving, and even thriving, in the twenty-first century retail landscape.

Review Questions

1. What does the author mean by a self-service retailer? How does this view differ from our traditional expectations of retailing and selling? What are the implications for shopper’s satisfaction with customer service or shopper’s ability to complete a shopping task efficiently?

2. Reflect on the preference for sales volume and shopper traffic over high margins on every product as business performance indicators. How did the Hartford brothers’ business model for A&P influence the development of self-service retail in the early twentieth century?

3. Why does the author consider retailers to be the biggest media companies? Explain how and why retailers are able to charge brand manufacturers for in-store promotions and catalogue advertisements.

4. Think of the examples the author uses of whispering (instead of shouting) at shoppers in a self-service grocery store. Can you think of other techniques to achieve the same result?

5. Describe the four purchase states. How can retailers use the understanding of these states to sell to shoppers more efficiently? What are the advantages and disadvantages of online and brick retail for each of the four purchase states?

6. Ponder on the convergence of online and bricks retailing. How can the efficiency of online shopping for Routine/Autopilot trips be combined with the immediacy (Now! and Surprise/Delight) of brick stores?

Endnotes

1. Sorensen, H. (2013, April 5). Retailing: The Trojan horse of global freedom and prosperity. Retrieved from http://www.shopperscientist.com/2013-04-05.html

2. Girard, J. (1989). How to Close Every Sale. New York, NY: Warner Books, Inc.

3. Sorensen, H. (2009, July 31). The Amazonian Ghost. Retrieved from http://www.shopperscientist.com/2009-07-31.html

4. Surowiecki, J. (2005). The Wisdom of Crowds. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

5. Sorensen, H. (2013, January 4). Whisper, don’t shout (or mumble!). Retrieved from http://www.shopperscientist.com/2013-01-04.html

6. Levinson, M. (2011) The great A&P and the struggle for small business in America. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

7. Martin, N. (2008). Habit: The 95% of Behavior Marketers Ignore. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

8. (2015, November 2) Introducing Amazon books at University Village. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/gp/browse.html?ref_=pe_2270130_154133930_pe_button&redirect=true&node=13270229011&pldnSite=1

9. Benedictus, L. (2014, January 7). “Inside the supermarkets’ dark stores.” The Guardian. Retrieved From http://www.theguardian.com/business/shortcuts/2014/jan/07/inside-supermarkets-dark-stores-online-shopping

10. Dorf, D. (2014, May 13). “Dark Stores.” Oracle: Commerce Anywhere Blog. Retrieved from https://blogs.oracle.com/retail/entry/dark_stores