7. The Quick-Trip Paradox: An Interview with Mike Twitty

The quick trip has become the most common unit of shopping, yet most retail stores are designed primarily for stock-up shoppers. We interviewed Mike Twitty when he served as shopper insights director of Unilever Americas in the U.S. Since then, he has opened his own company, First Light Insight (see sidebar). Throughout his career, he has conducted pioneering research on quick-trip shoppers. As he notes, although quick trips account for about two-thirds of shopping trips, shoppers buy many different types of products on these trips. This is the Quick-Trip Paradox. This means catering to the quick tripper is not as simple as defining a small set of “quick trip” products.

How Do You Define a Quick Trip?

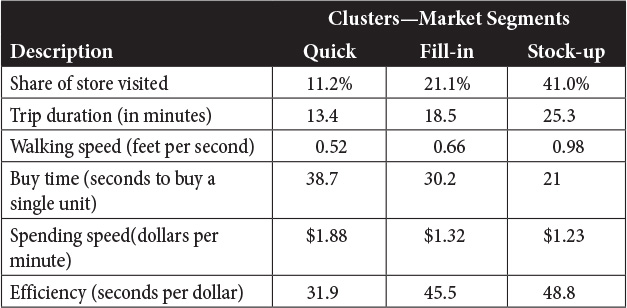

Twitty: In Unilever’s research, the term quick trip is a relative term that shoppers use to describe the amount of time, effort, and money they invest in a given trip to a retailer.1 Shoppers spend an average of about $100 on major stock-ups, about twice what they spend on fill-in trips (about $50), and four to five times what they spend on quick trips (about $20). Because quick trips are relative, they vary in size, depending on the retail outlet visited. A quick trip to a club store is substantially longer and has a higher spend (about $44) than a quick trip taken to a convenience store (about $15). One way to think about the terms quick trip, fill-in trip, and major stock-up trip is that they represent three different sizes of trips: the small, medium, and large trips that most shoppers take to their retailers.

The quick trip is different in frequency and purpose. In our research, we found that shoppers took an average of about 10 trips per month that resulted in a food purchase. Six of these were quick trips, and only one was a major stock-up trip. Fill-in and major stock-up trips both focus on buying items for the longer term or for restocking the household or pantry. Quick trips, in contrast, are focused on buying items that will be used shortly after purchase, usually the same day or the next.

If you spend enough time watching shoppers in most retail outlets, you will notice, among other things, that few of the shoppers actually shop the whole store. In addition, if you read the research that measures actual shopping behavior, rather than what shoppers say they do, you will see mountains of data showing that most consumer packaged goods (CPG)/food shopping trips are composed of a small number of items per basket. Considering these two observations, one obvious question is “why?” This simple question has driven a whole body of research aimed at understanding shopping trips, the shopping decisions that take place outside of the store, and how they affect the behavior that takes place within.

Why Do Shoppers Make So Many Quick Trips?

Twitty: The simple answer is: because they can. Because we have easy, affordable access to so many retail outlets, shoppers often choose to get what they want as they discover they want it. Instead of having to organize their lives around the availability of the retailer, they develop strategies to use the abundance of available retail options, cherry-picking them to best serve their changing needs. Although shoppers use a variety of strategies, the important thing is this: Most shopping trips to buy CPG and food items are quick trips, and quick-trip shopping is a unique opportunity for manufacturers and retailers.

Quick trips are a byproduct of our affluence and its effect on both U.S. households and our retail space. If we flash back in time, to some 78 years ago, the first supermarkets appeared on the U.S. landscape, and shoppers of King Cullen and Ralph’s delighted in taking advantage of two key benefits they offered: self-service and one-stop shopping. At that time, there were many fewer retail outlets, and shoppers had fewer opportunities to buy. In those days, shopping trips were infrequent, and planning before each trip was more important because running to a nearby store whenever you needed something was just not an option. Over the years, however, more and more retailers offered the items found in grocery stores and more and more retail space was built. Simultaneously, food and CPG items were also beginning to take smaller percentages of our growing incomes.

Looking over the course of time since the first grocery stores were created, we can see that as our household affluence increased and our retail options multiplied, the value of one-stop shopping declined. Today, we believe that with the great supply of retail alternatives available, when household money supplies expand or are in great supply, there is less of a need for one-stop shopping. When household money supplies contract or are in short supply, the value of one-stop shopping increases.

Although it is true that one-stop shopping and stocking-up are more economical ways to shop because they decrease the number of trips we take, our comparative affluence and easy access to retail has reduced our reliance on this practice. It follows, then, that quick trips are a convenience that has been enabled by easy, affordable access to retailers.

Another appeal of quick trips is that they enable shoppers to spend less time and effort planning. Quick trips make our lives more convenient by allowing shoppers to avoid the time and effort of planning before a shopping trip and by minimizing the need to live our lives limited by making sure that we have access to the resources available from our homes. Instead, shoppers can go more places and do more things because they can replenish their resources practically wherever they travel and whenever they choose. Regular stock-up shopping still takes place, usually on a weekly basis, and is vitally important in most households, but shoppers find themselves taking frequent, smaller trips to supplement their major stock-up trips. Although it’s true that increasing costs of shopping trips can change this pattern of shopping, for now it appears that quick trips are still the way that the majority of CPG and food items are shopped for.

How Do Pre-store Decisions Affect the Quick Trip?

Twitty: Before they enter a store, buyers of food and packaged goods have a relatively clear idea of what they want, and this knowledge steers them to visit some parts of the store while avoiding others. Unilever research shows that about 70% of all category purchase decisions (the decision to buy a product category such as mayonnaise or shower gel) occur before shoppers get to the store. Recent research from OgilvyAction found a similarly high percentage of such decisions were made outside of the store.2 Such pre-store decisions also play a great role in determining how much shoppers will spend on that trip. For manufacturers, understanding and influencing shopping behavior outside the store is at least as important as understanding and influencing what happens within. For retailers, some argue that leveraging shopping behavior outside the store is even more important, because it often determines whether the shopper will visit their store on a given trip.

As soon as a consumer decides to get something they need or want, they become a shopper, and shoppers have lots of decisions to make. Two of the more important decisions they will make are which store or stores they will choose to visit to get the items they seek and what type of trip they will make. In this context, the words “type of trip” are a kind of shorthand that describes the shopper’s objectives for a given trip and the personal resources they choose to invest in that excursion.

What Factors Do Consumers Consider in Deciding Where and How to Shop?

Twitty: For any given shopping trip we might choose to take, there are three primary considerations that shape the trip: 1) What do we need or want?; 2) How much money do we want to spend for what we need or want?; and 3) How much time and energy are we willing to devote to acquiring what we need or want?

Shoppers pit these considerations against their knowledge of the retail landscape to determine where their investment will take place. There are a host of other important considerations that follow these three, especially when focusing on shopping behavior within the store, but these three seem to be the most important considerations that determine the type of shopping trip they take and which store(s) will be visited.

How Do Consumers Think about Shopping Trips?

Twitty: Using our “trip management” research method, Unilever has studied over 20 million trips and years of household tracking with the general population and key subgroups, such as Hispanics and Baby Boomers. We pioneered the method in 2004, which enabled shoppers themselves to classify the types of trips they took, based on trip definitions determined from prior ethnography. Shoppers also indicated where the trips were taken and what was purchased. In addition, shoppers provided the researchers with their register receipts to validate the shoppers’ claimed behavior. This research was the first time CPG shopping trips across all major retail channels in the U.S. were measured attitudinally and validated with actual purchase behavior. The result was a powerful look across the major retail channels and retailers, as well as most CPG categories. It provided new insight into how people shop for CPG/food categories and how they use retailers to achieve their shopping goals.

One important distinction from other shopper studies is that the trip classification in this research was done by the shoppers themselves, rather than inferring or guessing at the shopper’s motive based on the items purchased. The way it was done was very simple. After each shopping trip that included a food item, shoppers were asked to answer two basic questions about the trip:

1. How would you best describe this trip?

![]() Major stock-up trip

Major stock-up trip

![]() Fill-in trip

Fill-in trip

![]() Quick trip—to get a few items for a meal to be eaten within the next day or two

Quick trip—to get a few items for a meal to be eaten within the next day or two

![]() Quick trip—to get a few items

Quick trip—to get a few items

2. What was the main reason for the trip?

![]() To restock the pantry or kitchen

To restock the pantry or kitchen

![]() A routine grocery shopping trip to buy items for today

A routine grocery shopping trip to buy items for today

![]() A routine grocery shopping trip to buy items for the next day or two

A routine grocery shopping trip to buy items for the next day or two

![]() To get an urgently needed item or two, quickly

To get an urgently needed item or two, quickly

![]() To take advantage of a special offer

To take advantage of a special offer

![]() Just to get out, to look around, or have fun

Just to get out, to look around, or have fun

![]() To shop for a special occasion (for example, for guests, a party, or the holidays)

To shop for a special occasion (for example, for guests, a party, or the holidays)

![]() To get “ready-to-eat” items to eat/drink right away or before I return home

To get “ready-to-eat” items to eat/drink right away or before I return home

![]() To purchase a nonfood item (but I eventually purchased a food item)

To purchase a nonfood item (but I eventually purchased a food item)

All household shopping trips that resulted in a food purchase were tracked over a two-week period, resulting in over 4,400 trips from about 900 households, across all major retail channels and most CPG/food categories. Since this first study, we have removed the limitation of looking only at trips that resulted in food purchases and now track households over the course of a year or more rather than just two weeks. Looking at all of these results has enabled insight into the basic patterns of CPG/food shopping.

What Did You Learn from This Research?

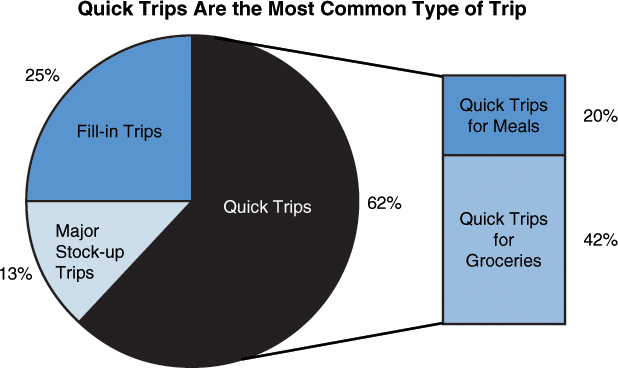

Twitty: Quick trips are the most common trip for consumer packaged goods or food shopping. Shoppers classify the majority of their trips to buy CPG or food items as quick trips. In Unilever’s original research published in 2004, “Trip Management: The Next Big Thing,” 62% of all trips were classified by shoppers as quick trips, as shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 When shoppers define their shopping trips as either quick trips, fill-in trips, or major stock-up trips, quick trips are the most common trip they report when buying groceries.

In recent trip management research where 11 million Nielsen-measured trips to all retail channels were monitored over the course of 2007, and all CPG trips were included, we found that 64% of the trips to purchase CPG categories were quick trips.

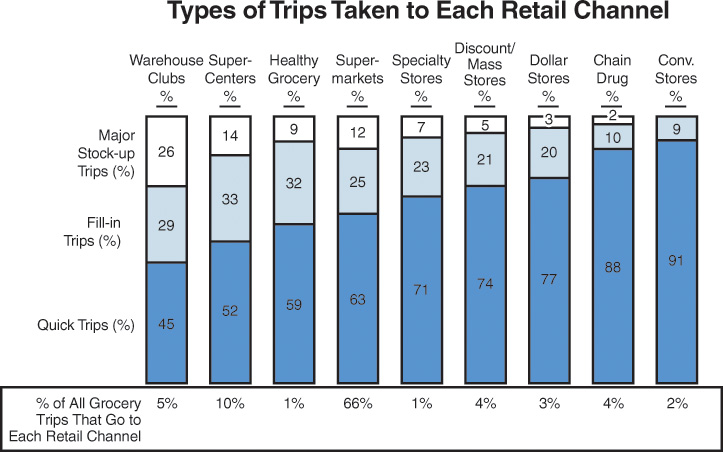

That such a high percentage of trips were quick trips was eye-opening, but what was absolutely shocking was that quick trips were the most common type of trip to every major retail channel—warehouse clubs and supercenters included! This finding has been confirmed every time the study has been replicated.

How Could It Be that Even Warehouse Clubs and Supercenters—Whose Design so Strongly Encourages Stock-up Shopping—Receive More Quick Trips than Stock-up or Fill-in Trips?

Twitty: The answer is that on most trips, shoppers are using these stores in ways that make the most sense for their busy lives and in ways that are possible simply because they have the financial resources to do so.

Figure 7.2 provides a great deal of information about the way shoppers use retail channels. You can easily see how shoppers use the different retail channels and the relationship between the size of the retailer’s box and the types of trips that shoppers take there.

Figure 7.2 Quick trips were the most common type of trip for every retail channel, even warehouse clubs and supercenters.

Given that Quick Trips Account for Two-thirds of Shopping Trips, How Can Retailers and Manufacturers Cater to these Shoppers?

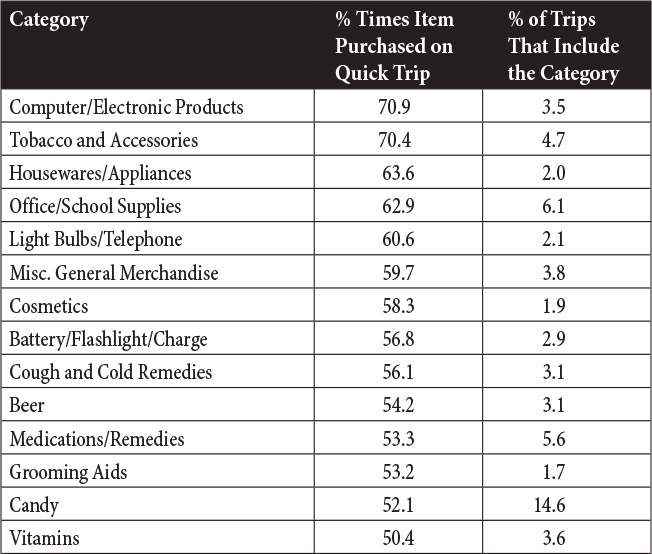

Twitty: It would seem that all we have to do is understand what shoppers buy on quick trips and we would have the basis for serving them better. Unfortunately, this is where things begin to get difficult. Looking at the 2007 data (featuring Nielsen’s Syndicated Category definitions and purchases from all outlets), we can see the troubling observation we call the “Quick-Trip Paradox.”

What Is the Quick-trip Paradox?

Twitty: The paradox is that although most shopping trips are quick trips, these shoppers are not coming to the store for the same products each time. In fact, we found that the average CPG category is purchased on a quick trip just 38% of the time. Quick-trip shopping must be composed of a very broad and changing variety of CPG categories. In a single week, a household might make a quick trip for milk, chips, and beer on one day, whereas a day or two later they might take another quick trip seeking light bulbs and paper towels. The following week might see a quick trip for antiperspirant, shampoo, and mouthwash. There just isn’t a concise set of related categories that would satisfy the range of shoppers’ needs on quick trips.

There are a wide variety of products that draw quick-trip shoppers to the store. This is a substantial impediment for anyone hoping to capitalize on the quick trip by dedicating retail space to serve these trips efficiently.

The Quick Trip Paradox: Although more than 60% of shopping trips are quick trips, the average consumer packaged good category is purchased on a quick trip only 38% of the time.

Given this Paradox, How Can Retailers and Manufacturers Capitalize on the Quick Trip?

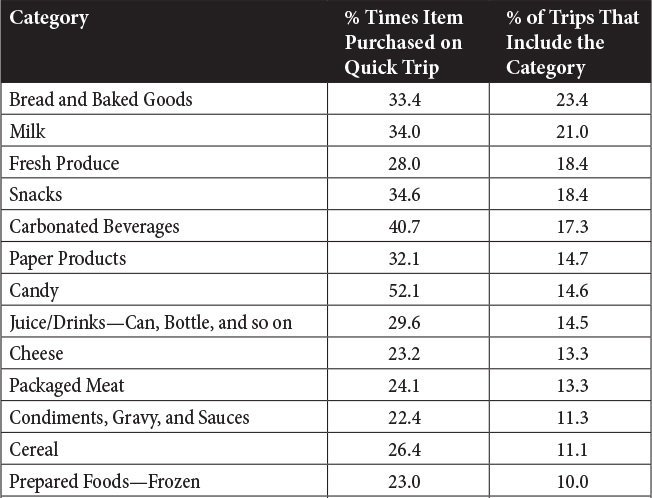

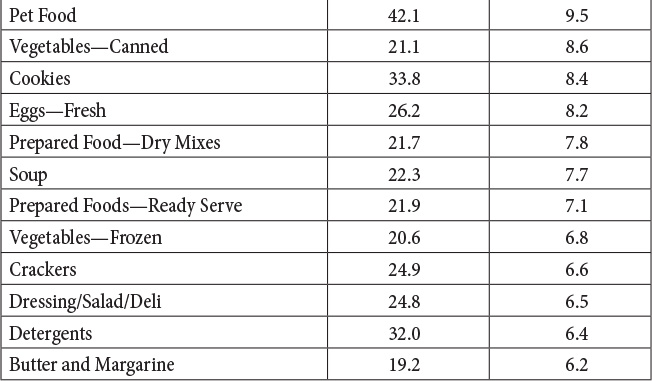

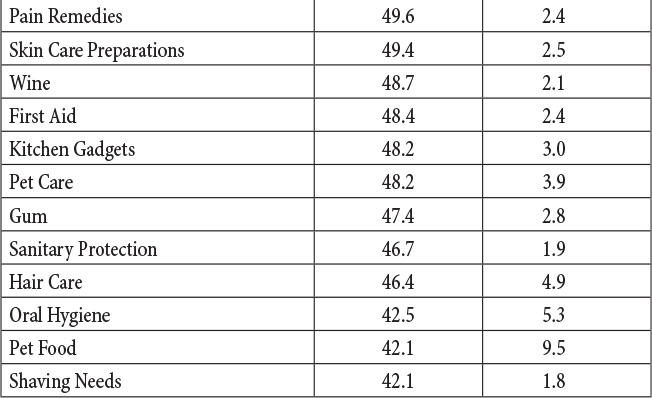

Twitty: Trying to identify the ideal assortment to satisfy the quick trip is maddening. There are no simple answers. Some categories are purchased more often on quick trips than the other trips. Out of roughly 120 categories, just 27 product categories are purchased mostly on quick trips. Table 7.1 is a ranking of categories that are more likely to be purchased on a quick trip. The categories that have the highest percentage of their purchases occurring on quick trips are at the top of the list. The table below excludes infrequently purchased categories, categories that are purchased on less than 1.5% of all trips.

Table 7.1 Top Categories That Are Purchased Most Often on Quick Trips, After Removing Slow-Moving Categories

Can you spot the link between these frequently purchased categories that are most likely to be purchased on quick trips? Is it clear what ties these items together? Can one understand what would be the best assortment and layout of a “quick trip retail space” by speculating on the underlying motivations of quick-trip shopping based on this list of categories? It’s very difficult!

Could the Shoppers’ Motives for Making the Trip Offer Insights into the Best Assortment to Offer?

Twitty: What is it that shoppers are seeking when on quick trips? Shoppers told us that when they were on quick trips, they usually wanted to accomplish their shopping quickly, and as we have already said, they were seeking items to be used or consumed in the very near future, meaning that day or the next. Unfortunately, the range of products that can be needed somewhat urgently, for that day or the next, is staggering because literally every product category qualifies. So, it seems that neither the shoppers’ known motives for taking quick trips nor the list of quick-trip categories provides the necessary insight to define a workable retail space tailored to serve the quick trip efficiently.

How Can Retailers Best Meet the Needs of Quick-Trip Shoppers?

Twitty: If we chose to assemble a collection of the most frequently purchased categories, we would probably have a much greater likelihood of attracting and satisfying those valuable shoppers who are in a hurry to get items they expect to use that day or the next. Stocking the most frequently purchased categories in a convenient way assures that you have the assortment for the broadest array of quick-trip shoppers. See Table 7.2 for the most frequently purchased categories across all outlets, as compiled by the Nielsen Company.

Bread, milk, produce, snacks, soft drinks . . . these familiar, high-frequency categories may provide a better basis for building a reasonably efficient “quick-trip retail space.” It would be a good idea to supplement this list with categories identified by a basket analysis against each of the most frequently purchased items. (A basket analysis identifies those items that are most often in the basket when a given item is purchased.) This analysis will identify the items most likely to be purchased, along with these high-frequency winners. Although it is focused on the most frequently purchased items rather than just those purchased on quick trips, organizing a retail space around these items seems to be a better basis for serving quick-trip shoppers—and all shoppers.

What Are the Implications for Retailers and Manufacturers?

Twitty: Retailers seeking to satisfy quick-trip shoppers should focus on how they manage their most frequently purchased categories. This is because satisfying shoppers on quick trips is not a simple matter of identifying those categories that are purchased most often on quick trips and making them conveniently available in a retail space. Quick trips do not center around a limited number of items that are always purchased on quick trips. Quick trips are composed of an impossibly broad array of items that are purchased on quick trips simply because they are needed for use or consumption on that day or the next. Such items range from soft drinks for immediate consumption all the way to items that are usually stocked-up on, such as light bulbs or batteries that, on this occasion, happen to be needed “right away” or for use in the near term.

Similarly, manufacturers should not be aiming to engineer products or “solutions” to be purchased on quick trips. Instead, they should focus on creating offerings that have high purchase frequency so that they have a greater likelihood of being purchased on any trip.

Review Questions

1. Describe the quick trip and how common they are. How do quick trips vary from other types of trips based on time, money, travel speed and store coverage? Which trip type is more economical?

2. Why do shoppers make so many quick trips? How would prevalence of quick trips differ: (a) in rural versus metro areas, and (b) at times of economic prosperity or downturn?

3. Why does Mike Twitty say that quick trips are a convenience? What do consumers “save” by doing quick trips, if those trips are less economical?

4. What purchasing state(s) discussed in Chapter 1 best describes the quick-trip shopper? How does this help retailers to better serve quick-trip shoppers?

5. What percentage of purchase decisions do shoppers make before arriving to the store? What are those decisions? What implication does this preplanning have for the concepts such as navigation, selection, affinity, and crowd social marketing discussed in previous chapters?

6. What is the Quick-Trip Paradox? What types of products do shoppers purchase most on quick trips? What does this knowledge mean for how retailers should plan their efforts to satisfy quick-trip shopper? What other analysis could be used to deal with the Quick-Trip Paradox?

7. What is the biggest difference between the broad range of “Quick Trips” that Mike Twitty describes, across all retail, and the typical “Convenience Store” trip?

8. Which is more likely to be “the store of the future,” the convenience store, or the super-center? Explain why each might be the store of the future; and also why each might not be the store of the future.

Endnotes

1. The terms “Quick Trip,” “Major Stock-Up Trip,” and “Fill-in Trip” have specific meanings in Unilever research so they are capitalized as proper names when used to refer to these definitions.

2. OgilvyAction, Shopper Decisions Made in Store, 2008.