2. Transitioning Retailers from Passive to Active Mode

By Mark Heckman

Over the span of more than 30 years in the food retailing business, I have come to grips with the concept that good merchandising will likely remain a mix of art and science. More than 30 years ago, as an eager but inexperienced assistant supermarket manager, I took great pride in planning and building impactful displays throughout the store. After completion, I would step back and admire my work. I took care to ensure the display was shoppable, meaning that the customer could easily access the items. The display had to be impactful, meaning it had to have a subjectively noticeable presence. And it had to be clearly priced. If my work met those basic thresholds, it was deemed a success (see Figure 2.1).

Fast forward 30 years. Those basic thresholds still rule the day in retailing. Retailers place products on the shelf or on special display with little or no regard to those products’ ultimate performance. Of course, retailers look at aggregate metrics such as item and unit sales, but for the most part, the process of retail merchandising remains much more of an art than a science. If a display looks good and it’s shoppable, the retailer has fulfilled their end of the retailer-shopper relationship.

Do these long-standing practices adequately serve retailers and their brand partners? Can retailers afford to rely on these practices alone, given the rapid rise of the data-rich, shopper-assisted, shopping environment presented by e-commerce competitors?

Passive Merchandising No Longer Suffices in a Shopper-Driven World

In Chapter Four of the first edition of Inside the Mind of the Shopper, Dr. Sorensen introduced the contrast between active and passive retailing. Passive retailing, in which retailers place products in stores for shoppers to find without knowledge of where the shopper would like to encounter those products, has been the norm for more than a century.

Contrast that with active retailing, in which the retailer understands who the shopper is and what the shopper is looking for when they take their predictable path through the store. By measuring the shopper’s in-store behavior, we generate the data the retailer needs to drive active retailing, guiding where to best locate displays, product placements, and cross merchandising efforts. As an example of active retailing, consider the top e-commerce sites that use past shopper behavioral data to place the right categories, products, services, and even advertisements in front of the shoppers.

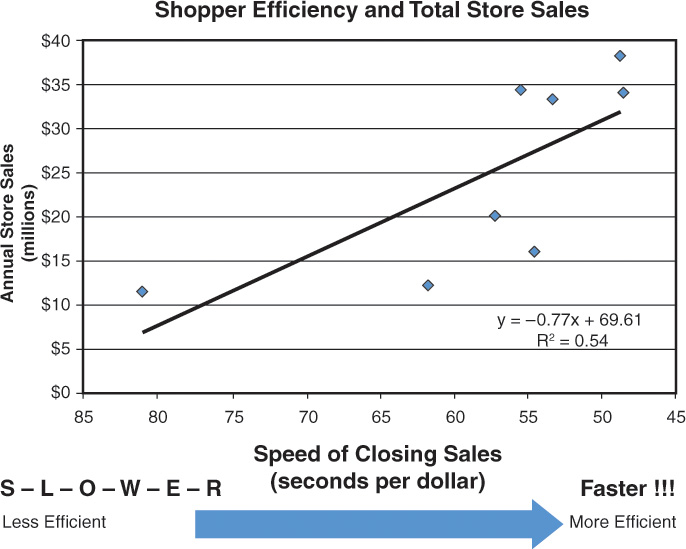

As shoppers become more accustomed to online shopping and its shopper-driven environment, their online experiences affect their expectations when shopping at bricks and mortar stores accordingly. They increasingly expect their in-store experience to mirror their online engagement. Bricks and mortar retailers that make the transition to active retailing and, correspondingly, to active merchandising will grow market share and be in a position to meet the demands of today’s dynamic shopper. The most compelling reason for active retailing is purely selfish: Active retailers sell more. The more efficient the retailer (shopper seconds per dollar), the higher the total store sales (see Figure 2.2).

Efficiency breeds sales, and in turn, higher sales drive further efficiencies.

The Journey to Active Retailing and the Five Vital Tenets of Active Retailing

Retailers seeking to become successful active retailers have decades of compiled shopper data and new technologies to enable them in their journey. Among the most critical metrics are those that involve shopper time management. In passive retailing, the retailer implicitly believes that the shopper has an unlimited amount of time to shop, read hundreds of signs, wander up and down aisles looking for products, and explore new departments. Based upon this false assumption, retailers bombard the shopper with new products, aisles, programs, signs, and now shopping apps, believing the longer they can keep the shopper engaged and in their stores, the more they will spend.

In active retailing, the retailer acknowledges that the vast majority of shopping trips are fill-in trips, in which shoppers buy fewer than five items. Even on longer, planned trips, the shopper’s internal clock ultimately determines when the shopper stops shopping and moves toward the checkout.

In passive retailing, the retailer is oblivious to the amount of time shoppers spend in their stores. In active retailing, they are obsessed with it.

Any retailer seeking to successfully engage the new in-store shopper should adhere to the Five Vital Tenets of Active Retailing. I offer these tenets not from the perspective of a scientist but rather as a retailer who has experienced over the years what the application of good science can do for the art of merchandising.

The Five Vital Tenets of Active Retailing

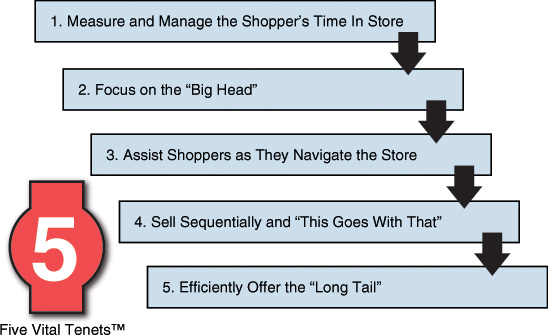

Each of these tenets (Figure 2.3) is independently important, but also inextricably linked to the others. Together, they form a road map for the retailer to follow on the journey to active retailing.

Figure 2.3 The Five Vital Tenets of Active Retailing are the yardstick for measuring the retailer-to-shopper relation.

The link that binds these tenets at the core of active retailing is grounded in three dimensions:

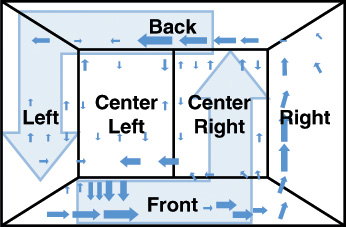

![]() Store geography: Physical attributes of the store such as left, right, center, front, and back.

Store geography: Physical attributes of the store such as left, right, center, front, and back.

![]() Shopper behavior: Where they go, what they buy, how long and how fast they shop.

Shopper behavior: Where they go, what they buy, how long and how fast they shop.

![]() Product performance: What products are purchased and how those products perform across the store.

Product performance: What products are purchased and how those products perform across the store.

I am convinced that the Five Vital Tenets of Active Retailing, as we explain them in this chapter, will transform the retail industry and propel the retailer into a new relationship with the shopper. The Five Vital Tenets are:

![]() Measure and manage the shopper’s time in store.

Measure and manage the shopper’s time in store.

![]() Focus on selling more of what we already sell the most.

Focus on selling more of what we already sell the most.

![]() Assist shoppers as they navigate the store.

Assist shoppers as they navigate the store.

![]() Offer selling events in a sequential manner.

Offer selling events in a sequential manner.

![]() More efficiently manage those items that sell the least, but occupy the majority of space and inventory costs.

More efficiently manage those items that sell the least, but occupy the majority of space and inventory costs.

As we examine each of the Five Vital Tenets of Active Retailing, the dimensions of store, shopper, and product will synergistically produce new success metrics, a new merchandising approach, and new ideas to drive sales and shopper satisfaction.

Tenet 1: Measure and Manage the Shopper’s Time in the Store

Retailers of all stripes will likely agree that what you cannot measure, you cannot manage. So is the case with managing the shopper’s time in the store.

As a retailer, I do not recall ever talking about shopper trip length or why it might have a role in successful merchandising. Retailers assumed the longer the trip the better because the shopper had more time to spend more money.

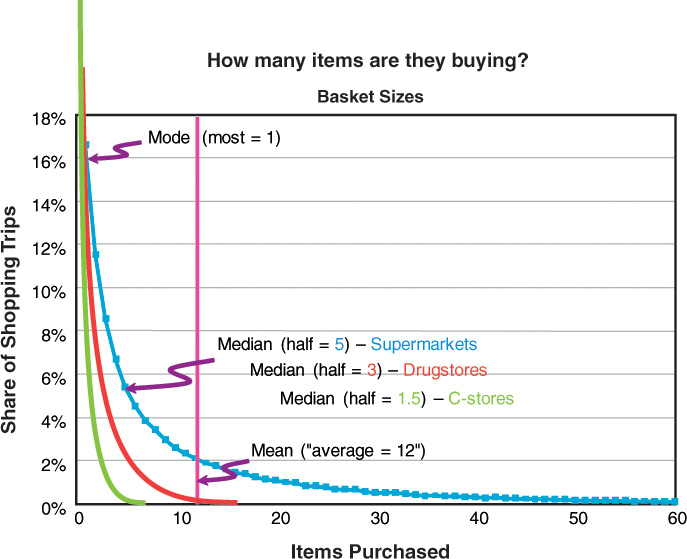

In actuality, most high-volume retailers are surprised to learn how few items shoppers purchase on any particular trip. Figure 2.4 shows that the median number of items shoppers purchase in a supermarket is just five items. But more importantly, the trend line is moving dramatically in the direction of smaller, more frequent trips to most retailers. This is especially true for supermarkets. Smaller transaction sizes mean a shorter amount of time spent on each trip.

Figure 2.4 The median trips (half larger baskets, half smaller) are a good index across individual retailers and classes of retail including across countries.

A Shopper’s Time Should Be as Important to the Retailer as It Is to the Shopper!

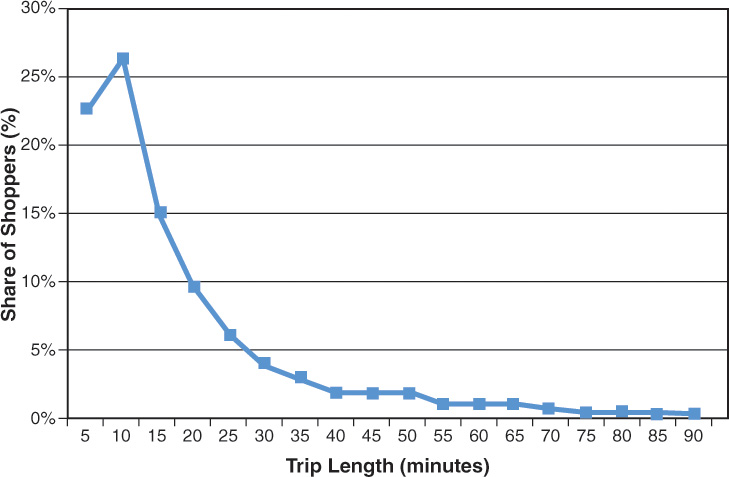

Retailers are sharing their shopper’s time with other retailers, both online and in-store, as well as with many other non-shopping demands for the shopper’s time. As just one example of the scant amount of time supermarket retailers have to reach their shoppers, Figure 2.5 indicates the average trip length in this particular store is just a tick over 16 minutes per trip, with the specific store involved in this measurement being approximately 50,000 square feet. Some quick math reveals that spending that little amount of time in a store that large does not provide the shopper adequate time for a casual stroll, let alone for a thorough exploration of all the merchandise the retailer placed out for the shopper to buy.

Wasted Days and Wasted Nights

Country-western singer Freddie Fender must have just finished shopping for groceries when he recorded his most famous song, “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights.” Crudely (but aptly) put, shopping in bricks and mortar stores is a big waste of time. Studies reveal that depending upon the size and layout of the physical store, as much as 85% of the time shoppers spend in a store is spent searching, not buying. This is a problem for retailers for two reasons:

![]() Shoppers have only so much time to spend shopping. If they are spending only 15% of that time actually buying, and the rest of their time is wasted searching, then retailers are suppressing their own sales.

Shoppers have only so much time to spend shopping. If they are spending only 15% of that time actually buying, and the rest of their time is wasted searching, then retailers are suppressing their own sales.

![]() In the past, when every store was equally inefficient, there was no significant risk of losing shoppers due to their frustration of not finding what they are looking for more quickly. These days, however, Amazon, other online retailers, and smaller bricks-and-mortar formats now offer more efficient alternatives.

In the past, when every store was equally inefficient, there was no significant risk of losing shoppers due to their frustration of not finding what they are looking for more quickly. These days, however, Amazon, other online retailers, and smaller bricks-and-mortar formats now offer more efficient alternatives.

After they’re confronted with the trip length and the basket size item count, the intuitive reaction from most retailers would be to take steps to slow the shopper down and to use promotions to lure shoppers down aisles typically not traveled. Both practices represent the old thinking of passive retailing.

Active retailing dictates that retailers do the hard work of making it easier for the shopper to buy more in the same or less amount of time they usually spend in the store. Why does this work? The simple answer is: because that’s what the shopper wants. The deeper answer, however, taps into the shopper’s habits. To effectively bring the product to the shopper, the retailer must reach the consumer within their habitual behavior. Anytime a retailer can sell to the shopper as a matter of habit, good numbers follow. I will discuss understanding the shopper’s habits as we explore the other tenets of active retailing.

Implications for Active Retailing

Being an advocate for the shopper and their time is the essence of active retailing. After you have measured shoppers’ time and their spending efficiency (dollars per second, or its inverse, seconds per dollar), the next steps involve using the other four tenets of active retailing to sell more to shoppers without extending their time in store. Just as important, it is in neither the retailer’s nor the shopper’s best interest to try to manipulate shoppers into areas of the store where they have no interest in going on that particular trip.

We derive shopper time management metrics from shopper behavioral data that is now available due to improvements in both technology and process. As with any new metric, its importance is commensurate to its link to existing key performance indicators, including sales, margin, transaction size, item counts, and even dollars per space.

Steps for Managing Shoppers’ Time in Store

There is an old saying, that what you do not measure, you cannot manage. So here is a brief outline of how to use the measurement of time, incorporated in your retail metrics, to gradually and surely increase the efficiency of the shopping process—and thereby the amount of sales produced.

1. Measure trip length in a representative sampling of each store format or layout design.

2. Through shopper tracking (through human observation or through technology), establish where shoppers are predominantly shopping, navigating, and spending time in the store. This will determine the Dominant Path.

3. Create benchmarks of performance, particularly dollars/minute, from the list of metrics provided; and merchandise with a focus on improving the speed in which shoppers are buying.

4. Develop an understanding of new time-related metrics and their links to traditional metrics such as sales, customer count, and basket size.

Tenet 2: Focus on the Big Head

When I think of supermarket merchandising, I think of the amazing amount of products that retailers manage to place in their stores, with the knowledge that each of those products carries an expense or holding cost. Despite the heavy cost of inventory, some of the very best retailers have expanded both the size of their stores and the inventory that populates the many aisles and departments.

The big-store strategy is founded on the belief that bigger is better and variety attracts shoppers. But with e-commerce competing with bricks-and-mortar stores in an already overstored marketplace, their unspoken strategy must be that their size and might will also eliminate the vast majority of their bricks-and-mortar store competition.

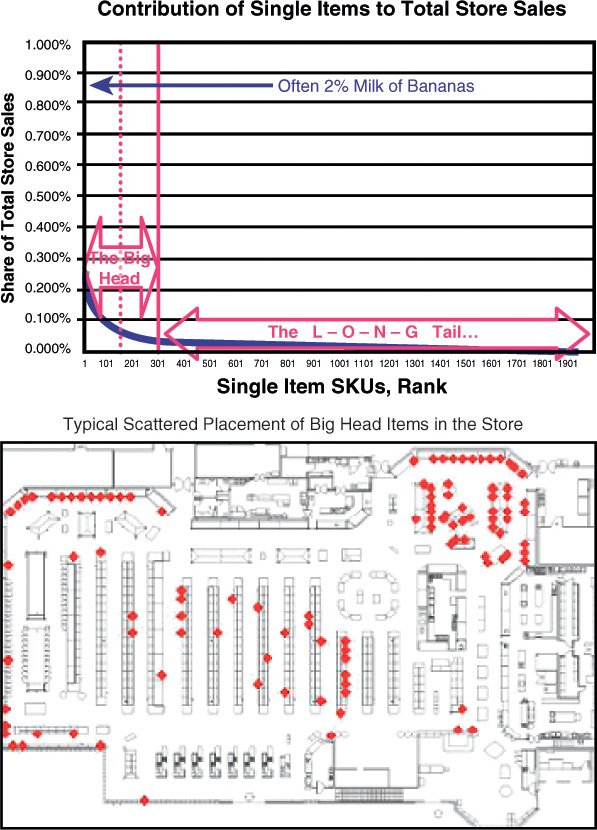

The big-store strategy carries with it significant risk. A demonstrated unwillingness to spend precious time navigating large stores reveals a shopper that is screaming at retailers to bring them what they want to buy without making them wade through miles of aisles. The numbers do not lie. Fewer than three hundred items comprise the list of frequently purchased items in the supermarket (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 Tenet 2 is about managing the Big Head, what shoppers are most interested in, those few items that generate an outsize share of total store sales.

Club stores like Sam’s, Costco, and B.J.’s directly addressed this issue by selectively carrying only bestselling items. Rather than having dozens of brands in a category, they pick the top-selling one, two, or three items to offer to shoppers. These Big Head stores predictably produce very efficient shopping trips in large part because they don’t handle the thousands of items that produce a scant few of actual sales.

We appropriately call these slow-selling items the Long Tail, and we specifically address a strategy for active retailers to address the Long Tail later in this chapter. Think of the Long Tail as the thousands of items that populate the shelves of the supermarket only to be purchased by a scant few shoppers on a scant few shopping trips, as opposed to the few items that make up the Big Head, which most shoppers purchase on most shopping trips. Passive retailers deem Long Tail items necessary to establish an image of significant variety and to provide the shopper with confidence that even infrequently purchased items are available as needed.

In active retailing, the Long Tail becomes an opportunity for the retailer to conveniently make many items available on demand and yet not stored in the physical store, or on the customers’ immediate path. We discuss managing the Long Tail later in this chapter.

Implications for Active Retailing

Retailers do not do themselves any favors by burying the Big Head among the Long Tail. But that’s exactly what most retailers do as they stubbornly rationalize that shoppers will do the hard work of finding what they need among the clutter. They tell themselves that although shoppers must wander through miles of aisles, they may pick up a few Long Tail items not on their list for this particular trip.

Active retailers take the opposite approach. They understand, as most marketers have learned over the years, that it is much more productive and sales advantageous to enable shoppers to buy more of what they are already buying than to burden them with a time-consuming fishing trip, trying feverishly to lure the shopper into buying items not on their list. That is not to say that smart cross-merchandising is a bad idea. In fact, later in this chapter we discuss how product adjacencies and category affinities are essential to executing smart cross-merchandising.

The quintessential active retailer, Amazon, and other online retailers have opened a new world to shoppers who are quickly becoming accustomed to having their favorite items presented to them based upon past shopping trips. Bricks-and-mortar stores must respond in kind. Like it or not, Amazon is changing the shopper’s expectations.

Many retailers have recognized that sales in their big stores have either peaked or the rate of growth has slowed. In response, retailers such as Walmart, Raley’s, Whole Foods, and Ahold/Delhaize are experimenting with smaller store formats in hopes that these stores reinvigorate the sales productivity necessary for growth and long-term profitability.

Shopper behavioral research, coupled with an understanding of the ways shoppers’ activities in the stores are linked to actual sales at the checkout produces a wealth of information—not just about the shopper, but also about the product category and the in-store real estate in which that product resides. As a retailer, I was an unwitting advocate of many category management segmentation practices, the most common of which involved determining whether a category was a destination category, meaning whether shoppers would seek out this category no matter where in the store it was positioned, or an impulse category, meaning that the category was more discretionary. As the name implies, shoppers usually do not plan to purchase items from the impulse category. Rather, they purchase those items because they are enamored with the merchandising or product as they pass by.

As a passive retailer, I was a firm believer that this rather intuitive perspective on categories was not only accurate but was a core rationale for placing Big Head items throughout the store, thus manipulating the shopper to these areas and thus increasing the exposure of these often higher-margined, impulse items.

Retailers Attempting to Manipulate or Extend a Shopper’s Trip Are on a Fool’s Errand

I have no doubt, even today, that some key departments and categories remain destinations for shoppers and that collateral impulse sales can be created by forcing shoppers to make long treks back to the dairy for milk or the produce department for bananas and lettuce. Shoppers, however, are becoming increasingly less malleable when it comes to their convenience. With this more disciplined shopper, retailers who sprinkle Big Head items throughout large store footprints run much greater risk of losing the sale of the Big Head item altogether, not to mention losing any residual impulse sales along the way.

I also believe retailers lose sight of the fact that shoppers don’t buy “categories”; they buy specific items. With the advent and maturation of category-management practices, retailers have been able to deal with merchandising and handling 75,000–100,000 items per store by grouping and managing them categorically. The shopper does not have that luxury. Active retailing does indeed recognize the critical importance of managing the store by departments and categories, but it also encourages retailers also to understand the importance of identifying the top selling items across categories, because it is the item that the shopper will buy . . . not the category.

Smaller store footprints logically create an inherently more efficient shopping environment, because there is less in-store real estate to navigate. However, simply creating a smaller version of a store designed for passive retailing is not the comprehensive solution active retailers must attain. The mandate for both large and smaller physical store footprints is to become more shopper-centric as they merchandise and plan their stores.

Steps in Managing the Big Head

Managing of the Big Head alone is the reason Big Head only stores like Costco are super-successful. Managing the Big Head in the presence of the long tail, but not “hidden” in it, is the key to superior performance Big-Head-plus-Long-Tail stores.

1. Identify those items that drive the majority of sales and frequently find their way into your shopper’s baskets.

2. Insure many of those items are within convenient access, and readily, distinctly seen on the established Dominant Path of shoppers.

3. Do not position these items as magnets to manipulate shoppers into specific, less trafficked areas of the store, but rather merchandise these items where the shoppers currently go in the store.

4. Understand which Long Tail items have strong affinities with specific Big Head items and create smart cross merchandising opportunities to exploit those affinities.

Tenet 3: Assist Shoppers as They Navigate the Store

When the active retailer is in position to measure and manage the shopper’s time in-store and is armed with the knowledge of which Big Head items drive the majority of sales, he is poised to take the next logical step by creating a shopper-assisted environment, much like the online environment with which shoppers are becoming enamored.

In a sea of thousands of items and messages, shoppers are often challenged to find what they are looking for in the small amount of time they have in the store. In fact, most shopping studies reveal that up to 85% of the shopper’s time in store is spent moving and searching, not buying. Because the average supermarket trip is just a tick more than 16 minutes, this leaves the actual buying time in the average trip at about two and a half minutes.

Tenet 3 is all about helping the shopper find what they are looking for. In doing so, we do not address or advocate the use of digital signage, shopping apps, and other technologies designed to communicate to the shopper along their in-store trip. Rather, we acknowledge that those shopper aids have value only if they save the shopper time and effort instead of adding additional steps in their shopping process. Most importantly, these technologies are only successful if the store layout and the merchandising are positioned to make the shopper’s trip more efficient.

When enhancing shopper navigation, the best place to start is with some startling facts. Consider these results from a recent shopper behavioral study from Forrester;3 many of the findings were sourced from Dr. Sorensen’s work.4

![]() The typical shopping visit lasts only 13 minutes.

The typical shopping visit lasts only 13 minutes.

![]() 80% of a shopper’s visit is spent looking for items in a store.

80% of a shopper’s visit is spent looking for items in a store.

![]() There is a direct correlation between the speed at which people shop and total basket size. Short trip shoppers spend faster and tend to buy more (higher per unit of time).

There is a direct correlation between the speed at which people shop and total basket size. Short trip shoppers spend faster and tend to buy more (higher per unit of time).

![]() Only 25%: the amount of store typically walked per visit.

Only 25%: the amount of store typically walked per visit.

![]() Average number of SKUs purchased monthly per household is only 150 (total); 83 (in grocery).

Average number of SKUs purchased monthly per household is only 150 (total); 83 (in grocery).

![]() As many as 50% of all grocery trips result in five or fewer items purchased.

As many as 50% of all grocery trips result in five or fewer items purchased.

![]() In grocery, as much as 30% of sales come from endcap displays.

In grocery, as much as 30% of sales come from endcap displays.

![]() As few as 80 items can constitute 20% of a large grocery’s sales.

As few as 80 items can constitute 20% of a large grocery’s sales.

![]() Open space and wide aisles and checkouts attract more attention from shoppers.

Open space and wide aisles and checkouts attract more attention from shoppers.

![]() Shoppers read very little while shopping, responding more to colors, shapes, and images.

Shoppers read very little while shopping, responding more to colors, shapes, and images.

![]() Three to five seconds: How quickly humans process a scene.

Three to five seconds: How quickly humans process a scene.

Volumes could be written about the impact of any one of these observations. In my practice as a retailer, I can best relate to the observation of how we tend to merchandise and sign a store as if the shoppers have all day to spend with us while having no clue as to the short amount of time each shopper actually spends in the store, and how much we retailers provide for them to process in just a few minutes out of their day, that they will spend with us.

I assumed that shoppers were being efficient as they shopped my store, because people tended to be efficient with their lists and coupons in hand and because we were not getting complaints from shoppers about the store being poorly designed. Perhaps if I had known then that as much as 60% to 80% of a shopper’s thirteen-minute trip is wasted looking for products instead of buying, I might have been compelled to do something to improve shopper efficiency, although I would have had no idea where to begin. As a retailer, being continually exposed to towering runs of merchandise (Figure 2.7) in my own and competitors’ stores, didn’t encourage me to recognize how they were impeding access to those few high volume items the shoppers wanted to buy.

Figure 2.7 Tenet 3: Towering long runs of product hinder exposure and access (navigation) to other areas of the store.

Some years later, armed with some basic precepts from Dr. Sorensen’s past work, I had an opportunity to put some of what I had learned into action. As the marketing vice president at Marsh Supermarkets in Indianapolis, I was called to a fixture plan meeting with the center store merchandising director and his space management team.

Knowing that I had worked with Dr. Sorensen on past projects, they were looking for ideas to improve the merchandising and price image of an older store that was finally getting a much-needed remodel.

Taking a quick glance at the fixture plan, and having spent some time in the store in question, I was immediately drawn to the very front of the store. As shoppers entered the store they were forced to take a hard left to move through a passage that had a wall-of-values promotional area called Stock Ups on one side and a long run of backlit shelving that housed breads and buns on the other. After shoppers had traversed at least sixty feet of this tunnel-like area of the store, they passed into a small floral department and then took a hard right through the produce department towards the back of the store.

Mr. Retailer, Tear Down This Wall!

This type of promotional presentation is not that unusual and arguably serves the purpose of presenting a strong visual price image to the shopper as they enter the store.

Conversely, past work done by Dr. Sorensen established that long, enclosed aisles naturally repel shoppers. I borrowed a famous challenge from President Reagan and encouraged my colleagues to “tear down that wall” of values and replace it with an open approach that enabled shoppers to have access to the promotional deals, but also to see what’s ahead of them in their shopping journey. Thankfully, that’s just what we did (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 Tenet 3: Replacing a wall of values with drop pallets opens sight lines to the center-store aisles.

The new configuration accomplished several positive results. More shoppers were drawn to the promotional area and more importantly, with the wall of values gone, the shopper had open sightlines to many of the critical center-store aisles and categories that were previously low traffic areas. Sales went up, more importantly; shoppers began accessing some of the key center-store aisles that were previously blocked from their initial view. Assisting shoppers as they navigate the store always pays benefits back to the retailer. Unlike this example, which involved removing aisles and fixtures, most navigational assistance can be done more easily and in a less costly manner.

Implications for Active Retailing

We have shown that creating open spaces and sightlines for the shopper is an area of opportunity by which many retailers can improve shopper navigation. It is also an important early step in becoming an active retailer because this move brings the product more aggressively to the shopper and enables the shopper to buy faster.

A second essential element of accomplishing accelerated buying is to identify something that every store has: a dominant shopping path.

Shopper tracking reveals both the direction and the intensity of shoppers as they navigate the store. Ideally the Dominant Path is established by measuring the direction of the shopper, the speed of their movement, the number of shoppers in a given area, and the time they spend in a given area. As Figure 2.9 indicates, the path typically forms a U-shaped pattern representing a dominant flow of shoppers from the front of the store to the back, along the back of the store some distance until a wide, inviting aisle is encountered, taking the shopper to the checkouts.

Figure 2.9 Tenet 3: A single Dominant Path is the virtual definition of efficient, convenient navigation.

When the Dominant Path is in place, the active retailer has a powerful tool to leverage. The path, exploited wisely, serves as a launch pad to build basket size, shopper count, and, consequently, sales, without keeping the shopper a second longer in the store than is helpful and comfortable to them.

The Dominant Path also serves as a bridge to the shopper’s habitual buying practices, where buying happens faster and more efficiently.

Activating the Dominant Path

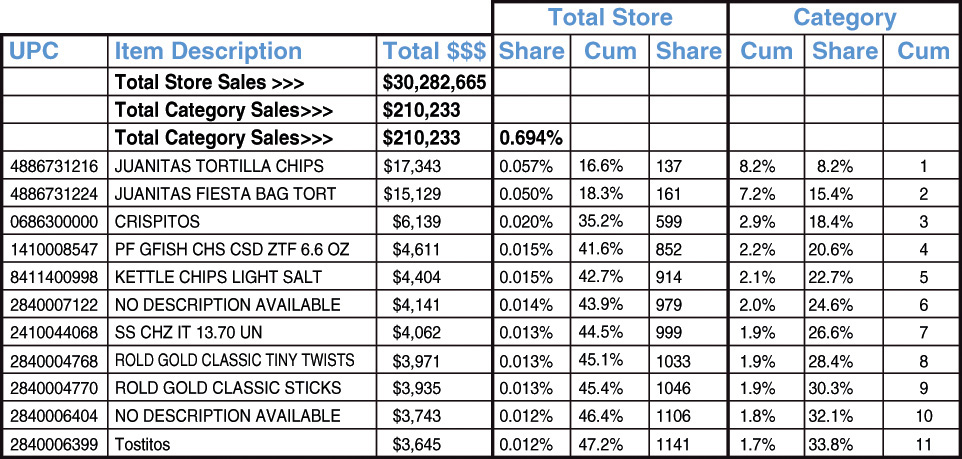

The Big Head plays a vital role in activating the path where the majority of shoppers navigate and dwell. As an initial practice, most retailers have the means of identifying those categories with substantial Big Head presence, the categories that drive a disproportionate amount of item and dollar sales. These are the categories that should predominate the Dominant Path because these categories will increase the buying efficiency as measured by dollars or items purchased per minute spent in the store, and correspondingly they will increase the retailer’s sales and transaction size.

Obtaining a list of top-selling categories and items allows the retailer to consciously merchandise these items to the Dominant Path and to other high traffic areas in the store. We also know that the earlier in the shopper’s trip progression you can present these items, the higher the likelihood for sales conversion.

Although it is understandably impractical to position every Big Head, high volume category in the store along the Dominant Path, it is possible to consciously position top selling items along the way as secondary displays, cut ins, and in-aisle bump outs, thus avoiding, at least initially, upheaving entire departments and categories in the process of activating the path.

The Dominant Path provides the retailer with an enormous venue to build incremental sales by bringing product actively to shoppers. But the remainder of the store has plenty of potential to do the same.

Figure 2.10 is a snippet from a category report that illustrates how to select items—in this case, salty snacks—to potentially be featured on the Dominant Path. The last three columns here tell the story for the category; these top 11 (of 88) items contribute one-third of the category sales. Simply stated, if we can increase the sales of this small group of items by 10%—a modest goal for focused TopSeller promotion—we will get a 3% lift for the full category. In achieving that 10% lift for these few items, it is better to focus on maybe only three of them, because getting outsize increases of 20+ percent for that small selection will lift this group by 10%. This is the way we focus on the few to lift the whole show, with modest increases in efficiency. The key to efficiency is focus, focus, focus!

Figure 2.10 Tenet 3: Top-selling categories and items provide a “seed list” for retailers to plant on the Dominant Path.

As a retailer, I found it difficult to accept the scientific fact that the location of an item within the context of other items in the physical retail store had as much to do with the category’s performance as the price of the product or even the product itself. In my discussions with brands and retailers, this provable premise rocked their world. We have all been indoctrinated into believing the 4 P’s of marketing: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion. Place was the least significant factor, not the most.

Working with Dr. Sorensen’s Vital Quadrant, which segmented categories according to their ability to convert passersby to shoppers and then shoppers to buyers, changed my view of drivers of category performance.

For the first time in my career, I could manage a category’s performance by the element of its position in the store. This is very important information for an active retailer.

As Figure 2.11 indicates, categories in specific locations fall into one of four buckets. We should note that the majority of categories are considered average performers and are excluded because there is much more potential available with the outlier categories.

Figure 2.11 Vital Quadrant analysis based on the Atlas5 modeling of category performance is a powerful tool in determining which products should be on the Dominant Path.

The result of this new category-segmentation system enables merchandisers to better understand the value of the real estate within their stores and to identify and leverage this information as a tool for cross merchandising, store layout, and category placements.

For example, if a retailer observes that the juice category is classified as a Leader category in one store but falls into the Niche bucket in another, a location change in the second store is worth pursuing because the category earned a Leader classification in the other store.

As the Vital Quadrant relates to the Dominant Path, the items and categories that earn leader or Niche classification in that store would be great candidates for placement or cross-merchandising along the Dominant Path. These categories tend to convert shoppers to buyers, and we know there are shoppers aplenty on the Dominant Path.

Steps in Assisting Shoppers as They Navigate the Store

Following is a good checklist of just what to do to work with shoppers’ intuitive, instinctive, distinctive shopping path. It is “the road most taken!”

1. Avoid displays and fixtures that hinder the shopper’s ability to see “what’s next.”

2. Provide the shopper options to navigate with wider, short aisle runs, if possible.

3. Identify the store’s Dominant Path in which the retailer can reach shoppers in the midst of their habitual shopping behavior.

4. Position and merchandise a strong mix of Big Head categories and items along the Dominant Path.

5. Cross-merchandise Long Tail items with strong affinities to the Big Head items that populate the Dominant Path.

6. After a category’s performance is identified in the Vital Quadrant analysis, merchandise Niche and Leader categories along the Dominant Path.

7. Do not spend great energy and effort attempting to lure shoppers to areas they do not heavily traffic. The investment of time and promotion will not produce positive results.

Tenet 4: Sell Sequentially

It is obvious that items are purchased one after the other. But it is also clear that items have affinities or attractions among themselves, so that purchase of some items may prompt the purchase of an affinitive item. Active selling means leveraging these relations, by proximities, but also serial order of presentation to the shopper.

What Comes First, The Chicken or the Egg?

In my 30+ years in retail, I have never understood the rationale (assuming there is one) that determines where retailers put things in the store. Not since 1915, when the Alpha Beta grocery chain introduced products stocked in alphabetical order, has there been any real attempt at clarity as to what should come first, the chicken or the egg? (Figure 2.12)

Figure 2.12 Tenet 4: Which comes first? The order in which offers are made to shoppers seriously affects sales. (Image © S-F)

Does the Order of Things Matter?

Having visited stores all over the world, I have seen seemingly as many different views and practices on product location as there are stores. The science of Sequential Selling states that the order and cadence in which shoppers encounter categories and items along their journey can either hasten or hinder their purchase efficiency.

Vital Tenet 4, Sell Sequentially, recognizes that overall department and product placement may be determined in part by the marketing objectives of that store or banner (that is, price, fresh, club). By understanding shopper behavioral science and category performance, however, we can present categories and items in an order that leverages the shopper’s habitual practices.

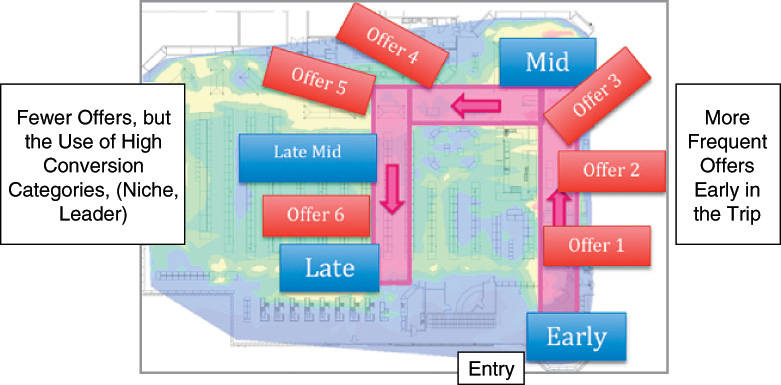

Sequential Selling is simply the practice of using shopper behavioral science to know how to place items in a store according to how the shopper habitually buys. Every shopper’s trip through the store has a cadence, whether it is just for a few items or for a stock-up journey.

To better understand Sequential Selling, imagine the store layout with the classic Dominant Path U-turn. First and foremost, a Sequential Sales plan is based upon the shopper’s journey. In our example store, the trip begins in a counter-clockwise fashion.

We describe the trip progression in four stages: Early, Mid, Late Mid, and Late (see Figure 2.13).

To effectively build a Sequential Sales plan around the Dominant Path, several shopper behavioral precepts serve as an effective context:

![]() The Dominant Path provides the medium through which to merchandise during the shopper’s trip progression.

The Dominant Path provides the medium through which to merchandise during the shopper’s trip progression.

![]() Understanding trip progression is critical. Shoppers spend faster earlier in the trip progression and, conversely, move faster and purchase less frequently towards the end of the trip.

Understanding trip progression is critical. Shoppers spend faster earlier in the trip progression and, conversely, move faster and purchase less frequently towards the end of the trip.

![]() Shoppers spend only a few seconds focusing on each sale event. Concise, well-placed signage and fixtures designed to communicate to the shopper’s subconscious, will most effectively engage the shopper and foster purchases.

Shoppers spend only a few seconds focusing on each sale event. Concise, well-placed signage and fixtures designed to communicate to the shopper’s subconscious, will most effectively engage the shopper and foster purchases.

![]() Sequential Sales events should be adequately spaced apart to allow the shopper time to focus on their planned needs and should be limited in number in order to create a presence and an aura of importance.

Sequential Sales events should be adequately spaced apart to allow the shopper time to focus on their planned needs and should be limited in number in order to create a presence and an aura of importance.

![]() Big Head items and Leader and Niche categories serve as the best candidates for Sequential Sales events because they have a strong track record of converting shoppers to buyers.

Big Head items and Leader and Niche categories serve as the best candidates for Sequential Sales events because they have a strong track record of converting shoppers to buyers.

Implications for Active Retailing

Sequential Selling serves as a natural extension of active retailing because it serves to bring Big Head and other categories with high conversion rates to shoppers as they traverse the store. Key to the success of a Sequential Sales plan is the creation of a visual image that is recognizable and memorable to the shopper, one that even reaches shoppers on a subconscious level where 95% of shopper decisions are actually made.6 Creating progressive sales events requires a level of discipline to avoid the temptation to over-merchandise and over-sign the store.

Many successful retailers traditionally flood their shelves with messaging to support new price programs, continuities,7 and the like. Although the overall impact of this approach presents an exposure for their programs, it does little to register in the shopper’s subconscious or to make a lasting impression about any one product in which they may be interested.

Finally, a silent, clean shelf look (Figure 2.14) creates the platform for effective communications when it is important to do so.

Starting from the position of a clean shelf, a simple but effective sign such as Top Seller (Figure 2.15) alerts the time-crunched shopper that other shoppers have made the choice to buy this product, thus giving the shopper confidence to do so as well.

Figure 2.15 The active retailer understands and connects with the shopper at a subconscious, habitual level. A few low-impact tags, well selected and placed, can drive a lot of out-of-stocks! (And that’s a good thing!)

A simple approach geared to send a subtle but effective message to the consumer helps the shopper wade through the thousands of choices presented to them and can be an integral part of a Sequential Selling plan.

Programs like Top Seller work due to their message design and the strategic and limited placement of signs. Too much of a good thing can certainly diminish the intended impact of the program.

In his book, Habit: The 95% of Behavior Marketers Ignore, Dr. Neale Martin writes that marketers are bombarding the consciousness of the shopper with signs, specials, displays, flashing lights, and great deals, even though it is the subconscious or habitual shopper that makes the majority of the decisions.

Although the passive retailer markets to the conscious shopper with thousands of signs and color-coded programs, the active retailer understands and connects with the shopper at a subconscious, habitual level in each phase of the shopper’s trip.

Steps for Sequential Selling

Summarizing a plan for sequential selling:

1. Begin with understanding the dynamics of shopper flow through the store and identify the Dominant Path of the shoppers in the store (Vital Tenet 3).

2. Use the same shopper observational research that provided the shopper traffic flow to assess where purchase conversion rates are strongest (Vital Tenet 3).

3. From there, tap the Big Head to identify a collection of categories and items that have high consumer interest and those that have a strong history of conversion (turning a shopper into a buyer).

4. Before making more cost-intensive decisions about moving entire categories in new, more shopper-centric locations, begin first with experimentation through placement of high conversion, Big Head items/categories in secondary displays, in-line cut-outs and endcaps.

5. Lastly, create a concise and disciplined communication plan to effectively reach the shopper during their trip progression, a plan that eliminates excess clutter and noise and focuses on messaging that helps the shopper make quicker purchase decisions.

Tenet 5: Managing the Long Tail

In our exploration of the first four tenets, we focused on efficiently bringing to the shopper the products that they buy on a regular basis. This strategy entails offering more of what the shopper is already buying instead of coaxing and prodding the shopper to try something new.

So Where Does This Leave the Tens of Thousands of Other Items That Populate the Shelves of the Store?

As a recovering passive retailer, I am not ready to advocate giving up on the Long Tail. Many of those items create the much-needed aura of variety that shoppers value and upon which some retailers build their reputations. There is cachet in having everything under the sun, but there is also danger.

I could fill the next few pages with charts and graphs that speak to the negative impact fostered by huge amounts of inventory on labor, holding costs, and cash flow. Those of us with retail experience well understand that. We do not need to turn this discussion into an economics lesson. We must recognize, however, that forces are at play in the marketplace that put bricks-and-mortar retailers, with large store footprints and heavy inventories, in peril:

1. Amazon and other e-commerce retailers have changed the shopper’s buying behaviors. Many items are now frequently purchased online instead of in the physical store.

2. These online retailers have decidedly logistical and financial advantages over bricks-and mortar-stores in terms of the cost of goods sold.

3. InstaCart, Peapod, and a host of other upstart delivery retailers are beginning to gain traction, especially with emerging urban-based affluent shoppers.

4. The emergence of a plethora of smaller bricks-and-mortar formats and stores offers the shopper the Big Head and limited portions of the Long Tail in hopes to capture the incremental sales.

5. Consequently, the shopper has more options and has greater mobility than ever before from which to source their needs.

“Nobody Goes There Anymore. It’s Too Crowded”—Yogi Berra

The late, great Yankee catcher could have very well been thinking about shopping in large stores when he uttered this famous line. Stores crowded with thousands of items are off-putting to mission-driven shoppers who know what they want yet must navigate through long aisles filled with merchandise that is of no interest to them to get it.

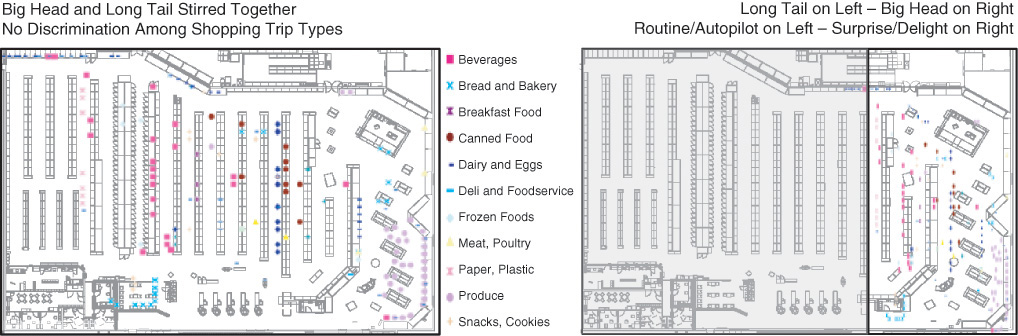

Inevitably, physical stores as we know them today must change. Retailers who once believed bigger stores were the prerequisite for success are now scrambling to downsize. Other stores are experimenting with the concept of “stores within stores” to afford shoppers more organization and definition during their trip. A longer view of managing the Long Tail suggests that the store format of tomorrow separates the Big Head from the Long Tail (Figure 2.16).

Figure 2.16 The store format of tomorrow separates the Big Head from the Long Tail, with a view toward moving the Long Tail progressively online.

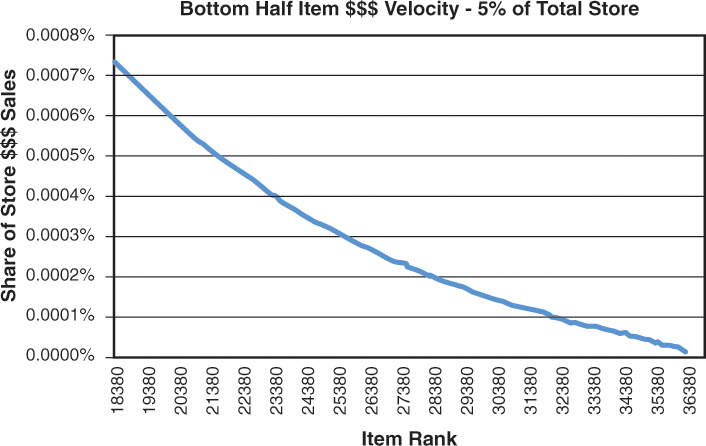

Passive retailers everywhere will likely initially balk at this divided approach, given its counterintuitive approach to the precepts of traditional merchandising. However, when viewing the sales contribution of the bottom 50% of items, most retailers would agree that the status quo is not sustainable.

The evidence is compelling. Figure 2.17 tells a very depressing story about the productivity of the bottom 50% of items, collectively delivering only 5% of total sales.

Figure 2.17 Many of these Long Tail items can be matched to specific Big Head items to enhance sales of both. Others will ultimately end up being sold online, within the bricks store itself. The pending “Long Tail Accelerator!” (Patent pending.)

Smartly assigning these items to a more productive role means reducing their store position and/or presence.

As we discussed previously, a significant number of these Long Tail items have affinities with Big Head items. Merchandising these items along with the Leader and Niche Big Head items on the Dominant Path surely will improve both the exposure and sales performance.

Implications for Active Retailing

As a retailer, I see managing the Long Tail as a dynamic balancing act. Shopper behavioral science has firmly established that shoppers prefer and are accordingly migrating to a shopper-assisted experience. This movement is diametrically at odds with large stores with tens of thousands of items placed across tens of thousands of retail square footage.

Savvy retailers are talking about and executing plans that optimize item selection, but in most cases these exercises do not address the impact on the shopper and their new behavior in a digitally driven marketplace.

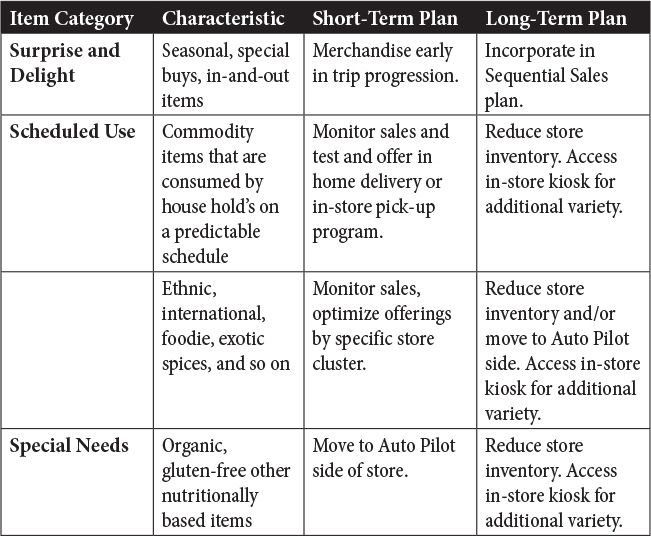

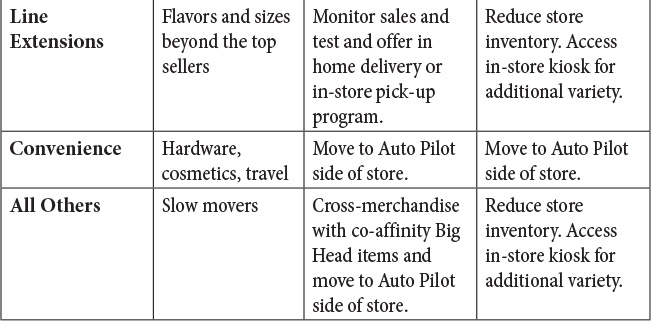

To address the vagaries of the Long Tail, an active retailer should consider both a short-term and long-term solution. Also, not all Long Tail items are alike, and we should not treat them as such. It is important to understand how the shopper views these items before we begin making decisions about their fate.

Table 2.1 shows a planned approach to identify and address the burgeoning item count in bricks-and-mortar stores. The strategies we propose here are viable, but retailers will need to make adjustments depending on their specific competitive environments, trade areas, demographics, and marketing positions.

Smartly segmenting items into manageable groups provides the retailer an opportunity to adjust store inventories down over time. In this process, many of the Long Tail retailers may continue stocking items on the shelf if they generate sufficient sales. These items may also warrant a secondary placement on the Dominant Path alongside Big Head items with which they have high co-affinity.

Other items may lend themselves to seasonal merchandising; still others may transition to availability only through e-commerce. Over time, as shoppers increasingly become comfortable with buying various items for in-store pick-up or home delivery, the number of items that a retailer can jettison off their shelves or into an e-commerce picking warehouse will grow.

In the interim, Long Tail item segmentation allows the retailer a systematic way forward to reduce inventories at store level, to improve exposure to selected Long Tail items, and ultimately to become a key tool in designing a dual-store design approach with Surprise/Delight and Auto Pilot/Routine areas of the store well defined.

Steps in Managing the Long Tail

A conceptual plan was offered in Chapter 1, to progressively migrate the Long Tail to online management. In Figure 2.17 reference was made to the pending Long Tail Accelerator, a device deployed by the retailer on the shelf, providing direct online access to product options no longer available on the bricks store shelves, but accessible either before the shopper leaves the store or by efficient delivery. No, all of this isn’t foreseen in every detail. But meanwhile, guidance on what to do right now in the store is outlined here:

1. Understand numerically which Long Tail items represent the best opportunity for cross-merchandising in key secondary placement locations along the Dominant Path.

2. Develop Long Tail item segments, providing a role and specific longer-term strategy for each.

3. Begin the transitioning process of discontinuing the practice of using Big Head items as “magnets” to draw shoppers into remote areas of the store a way from the Dominant Path for the purpose of increasing exposure to Long Tail items.

4. Conversely, sprinkle Long Tail items that have high co-affinities with Big Head items along the Dominant Path to increase their exposure and sales conversion rates.

A Passing Thought about the Role of Displays in Active Retailing

In active retailing, measuring the performance of displays is integral to the ultimate success of bringing the product to the shopper in a more efficient manner. The performance dynamics of displays, whether it’s an endcap, an in-aisle bump out, a free standing display, or a wing (side stack), must be more accurately and universally measured. For more information on special displays, refer to the Afterword.

Closing Thoughts

Practicing active retailing will not be intuitive for many seasoned merchandisers. It cuts across the grain of most everything retailers have considered standard practices for more than a century. For most of us, success was built upon huge stores, long aisles, and thousands of items, with signs and messages everywhere. We believed if we put the merchandise somewhere, the shopper would find it.

But as retailers struggle with declining sales, burgeoning inventory costs, and their customer’s increasing adaptation to online shopping, it is clear that the old model of passive retailing is no longer working as well as it has in the past. Shoppers with many options and new technology have irrevocably altered the playing field.

In the new active retailing environment, physical stores and merchandising schemes will be concise, clear, efficient, and always customer-centric. The in-store experience will increasingly resemble the online environment and the two will work in lockstep to provide the shopper with what they want, when they want it. Retailers must take an active role in bringing the desired products more efficiently to the shopper in the physical store.

Active retailers will be poised to grow their business across channels and customer touch points. New metrics such as dollars/second, sales conversion rates, category exposure, and many more will enable retailers to continually fine tune their store designs, fixture placements, category presentations, and merchandising plans. It’s a new day! The shopper is in charge and active retailing will become the new norm for reaching the shopper on their terms, not ours.

Review Questions

1. How have successful online retailers like Amazon change shopper expectations of modern retailing? What can bricks-and-mortar stores do to rise to such expectations?

2. What are the traditional (and false) assumptions of passive retailing regarding shopper time? Which metrics could a retailer use to reliably uncover how shoppers spend their time in-store?

3. Describe the concept of Big Head–Long Tail in merchandising. How do traditional passive retailers deal with these two groups of products? What is the assumption about shopper behavior that underpins that (traditional) strategy? What steps an active retailer could take to better manage the Big Head?

4. What is the most important factor in improving in-store navigation? What principles should be used in creating in-store environment and building displays?

5. Describe the Dominant Path in terms of shopper navigation and product assortment. How does assisted shopper navigation along the Dominant Path relate to sales?

6. Discuss the difference between a “clean aisle” and a “shouting aisle.” Why are shouting aisles ineffective (consider shopper psychology and visual attention)?

7. What is the attraction of the Long Tail from the shopper perspective? How can a retailer manage the Long Tail more efficiently?

Endnotes

1. Phua, Peilin, Bill Page, and Svetlana Bogomolova. “Validating Bluetooth logging as metric for shopper behaviour studies.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 22 (2015): 158–163.

2. Bogomolova, S., Vorobyev, K., Page, B., and Bogomolov, T. (2016) “Socio-demographic differences in supermarket shopper efficiency”, Australasian Marketing Journal.

3. Forrester’s The State of Customer Experience, 2010.

4. Lee Resource, Inc.

5. Atlas is a Category Location tool that can be accessed at http://www.shopperscientist.com/atlas/. A description is available at: Suher, J and Sorensen, H (2010). The power of Atlas: why in-store shopping behavior matters, Journal of Advertising Research, 21, March, pp. 21–9.

6. Neale Martin, “Habit: The 95% of Behavior Marketers Ignore.” (ISBN-13: 007-6092046561)

7. Continuities are merchandising programs that last for a number of weeks, like, “Spend $50 each week for the next 6 weeks and get $50 Off your next order” Or it could be a dishware or linen program where each week you get a new dish or towel for a great deal and complete the set at the end of the event period.