3. Selling Like Amazon Online and in Bricks Stores

Since we published the first edition of this book, the march of technological progress has moved dramatically forward. Shoppers have become accustomed to the speed and efficiency of online retail, and Amazon has led the pack in developing online retail practices. Many of the techniques Amazon uses harken back to the era of personal selling in retail, when shop clerks guided shoppers through the process of identifying and selecting the products that best suited their desires and needs. Here, we examine how Amazon has returned personal selling to self-service retail, and how it and other online retailers are driving a new evolution in retail as groundbreaking as the development of self-service retail a century before.

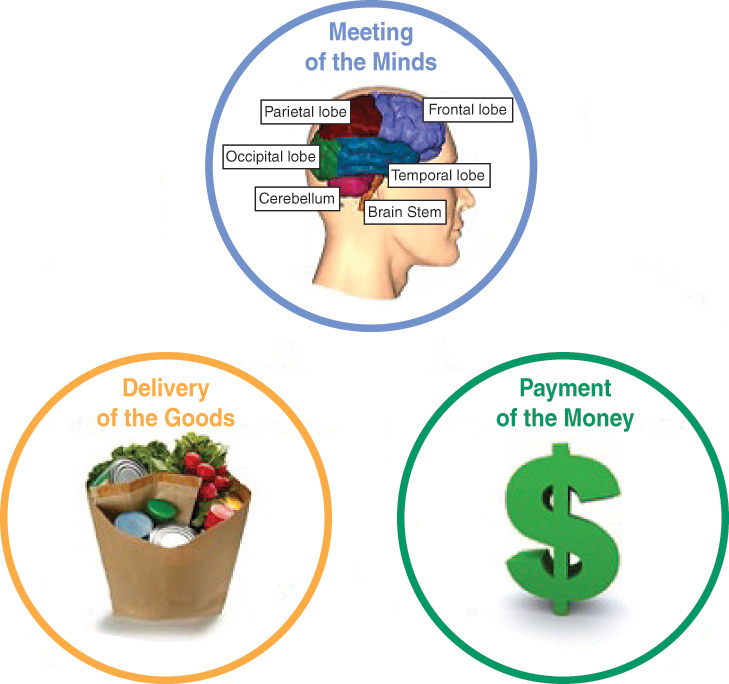

There are three basic functions in retail, whether it occurs online or in traditional bricks and mortar stores: meeting of the minds, delivery of the goods, and payment of the money. (See Figure 3.1.) The importance of the delivery of the goods and payment of the money should be obvious. However, the essential element of the meeting of the minds is not so obvious. It’s a legal concept that when a seller and buyer agree on the specifics of a transaction, their minds have met and a legally valid transaction, the sale, can occur. For our purposes here, we make a distinction between two kinds of mind meeting, mediated sales and unmediated sales. The mediated variety involves a clerk or salesman personally assisting the shopper. It is the clerk’s job to guide the thinking of the customer by providing a selection of products, information, advice, experience, and knowledge until he achieves a meeting of the minds when the shopper says, “Yes, this is the product I want at the price I am willing to pay.” This was the norm in retail until one hundred years ago when retailing began moving to the unmediated variety of sales through the self-service model. In unmediated sales, the shopper is left to explore their options, learn about the products, and to think their way through the purchase process on their own, unguided by a salesperson.

Amazon’s true advantage at retail is that they get to mediate the sale, like the store clerk of long ago; by guiding the shopper’s thought process, step by step and click by click. Admittedly, they do this with the aid of a computer algorithm rather than through personal interaction with shoppers. The process is nonetheless as interactive as a real salesman interacting with the shopper in a bricks store. Thus, Amazon mediates self-service sales with their computer algorithm acting as ghostly salesmen.

In this chapter, we focus on how Amazon has slipped mediation back into self-service retailing online. We also show how the Amazonian techniques can be adapted to a wide variety of self-service bricks stores even without the benefit of Amazonian technology. The good news is that Amazon’s selling advantage is not inherent to online retailing. Instead, it derives from the particular mental process through which Amazon guides its shoppers. It does not just passively stock merchandise and rely on shoppers to sell to themselves. The mental process a shopper goes through when making a purchase is remarkably similar in online and offline sales. This similarity was noted by Professor Peter Fader of Wharton:

“I figured the process of someone standing at a shelf and deciding what juice to buy is going to be very different than someone sitting at the computer clicking through a bunch of different books or CDs—until I actually looked at the data, and it turned out that the patterns were remarkably similar.”1

We will first identify five specific points of focus Amazon uses online: navigation, selection, immediate close, affinity, and crowd-social marketing, and reaching into the Long Tail. We will then see how these same five points can accelerate sales in bricks stores. Some are already doing it.

Amazon Selling Online

The mental process shoppers experience when making a purchase involves two steps. First, the retailer must make the offer. He accomplishes this by getting the customer and the merchandise together either by moving the customer or by moving the merchandise. Recall how we began this book by discussing the concept of bidirectional search, in which shoppers are looking for products whereas products, suppliers, and brands are looking for shoppers. We call the process of bringing shoppers and products together navigation. Second, to close the sale, the shopper must pick an option and accept the offer of the merchandise that she feels best meets her needs and desires at a price she is willing to pay. We call this part selection.

In the self-service bricks store, the retailer expects the shopper to move themselves, to navigate, to the merchandise. While online, conceptually, the retailer brings the merchandise to the shopper in response to the shopper’s click-click-click navigation.

Amazon has an advantage in managing the shopper’s navigation because they can deliver any offer to any shopper in a matter of a few key strokes, which only takes a few seconds. Bricks retailers, however, have a potential large advantage of their own with the much larger screen of the store. In the selling process, vision is the major connector between the shopper’s mind and the merchant’s mind.

Let’s now examine through the Amazonian lens these two basic parts of a shopper’s mental process, navigation and selection, by exploring five areas in which Amazon has a laser focus.

Amazon Point of Focus #1: Navigation—Simple and Fast

Greg Linden, former Amazon programmer commented, “We used to joke that the ideal Amazon site would not show a search box, navigation links, or lists of things you could buy. Instead, it would just display a giant picture of one book, the next book you want to buy.”2

Amazon’s mind is not on what they want to sell to the shopper. They make it easy for themselves by figuring out what is on the shopper’s mind and sell that to them. This is a billion dollar tip for retailers. The goal is to sell as fast as possible, because the faster you sell, the more you will sell, whether online or offline.

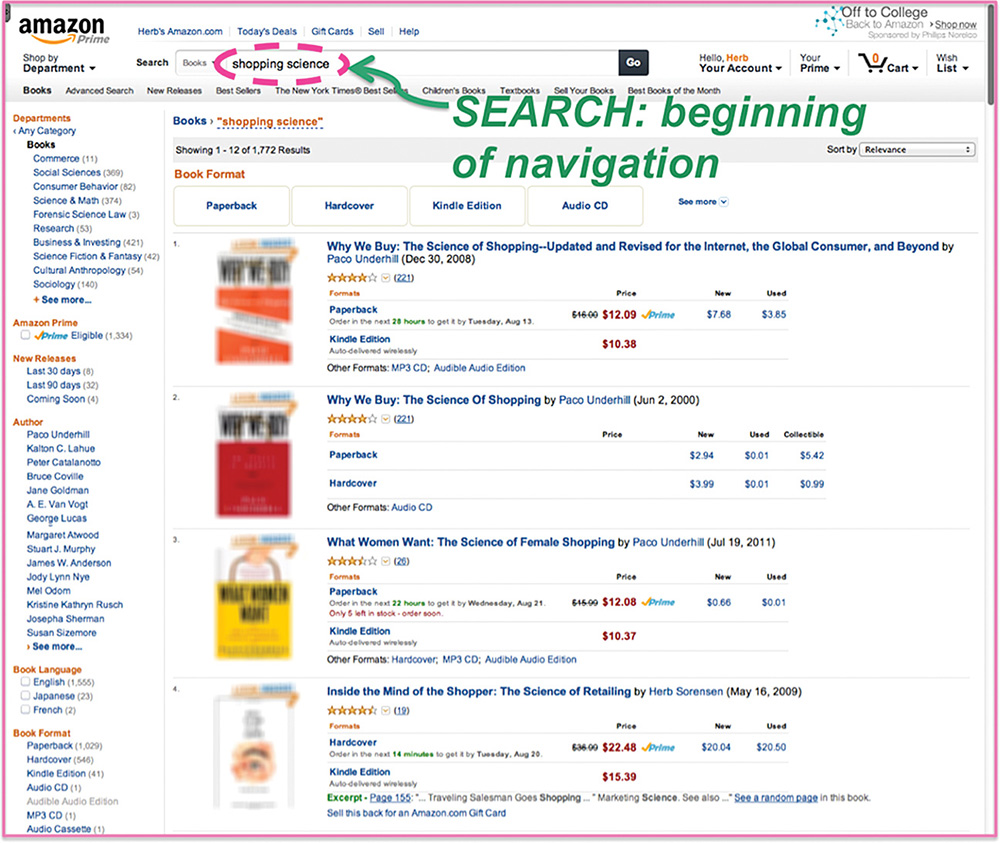

To think about how Amazon helps shoppers navigate their sales program, let’s imagine you are interested in buying a book on shopping science. From a conceptual point of view, selling books is not that different from selling “shoes and ships and sealing wax”—or anything else. Let’s see how Amazon begins with rapid navigation to the shopper’s probable purchase of a book about shopping science (Figure 3.2).

Exactly how Amazon’s search algorithm works is not important. What is important is that in about two seconds Amazon delivered a list of 1,772 books. This is typical Amazon: with a Long Tail of millions of books Amazon wants to bring you what you want as quickly as possible. Crucially, the algorithm has ranked the selection beginning with the number-one bestseller. This is because statistically the bestseller is most likely to be the next one sold out of this selection of books.

In fact, whatever you want to buy, Amazon will always take whatever clues it has and deliver you a ranked list. This is akin to the clerk in a bricks store showing you the product that most of his shoppers have found most satisfying. It is a prominent step in getting you to the book you want to buy and getting to the sale as quickly as possible. The book for you may not be number one in sales for the crowd. But the closer your book is to number one on Amazon’s custom list for you, the more successful the algorithm.

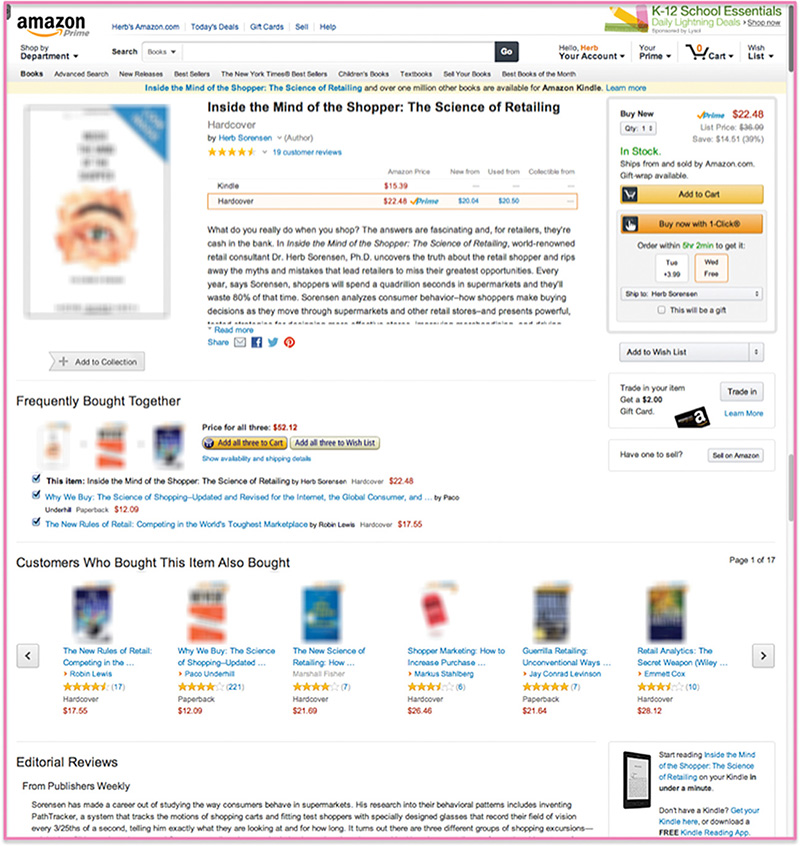

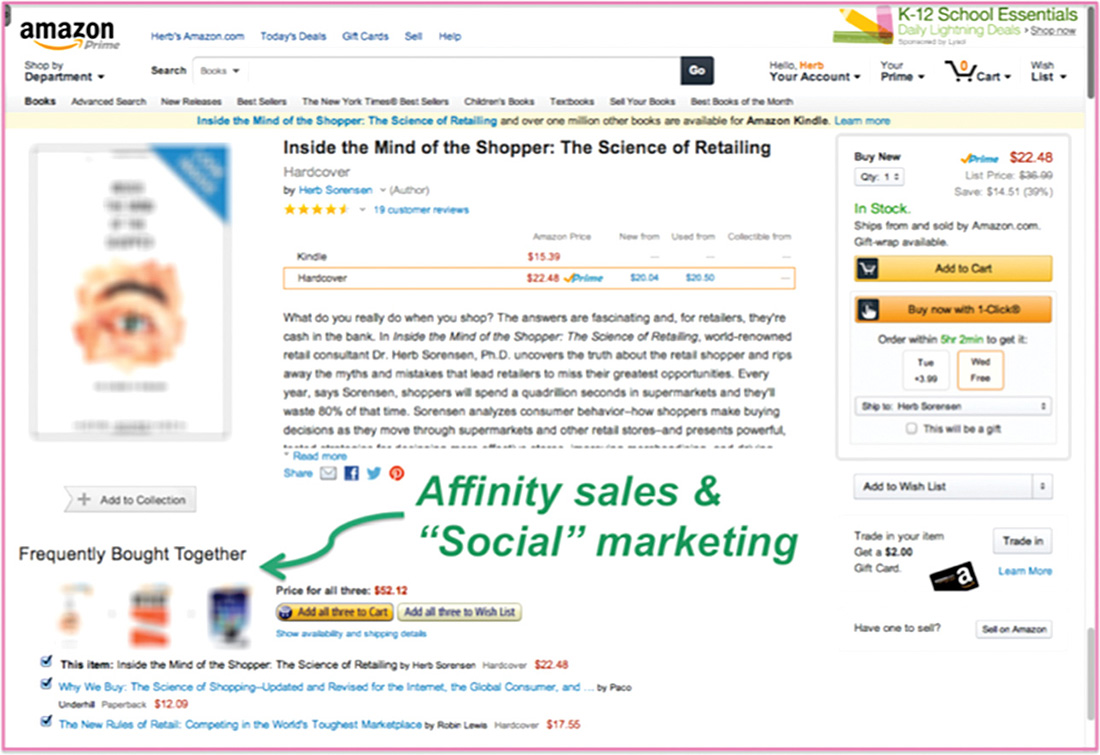

Amazon Focus: Selection

We can illustrate the selection part of Amazon’s sales program with a customer who has arrived at a single page representing a single book, which the customer may want to purchase. Let’s suppose the shopper is not familiar with shopping science books. She notices that although fourth-ranked Inside the Mind of the Shopper is not the top-seller of the top books, it is the most highly rated of those top few. So the shopper curiously clicks on it, bringing up this page; we are now ready to explore the remaining four areas of Amazon focus (Figure 3.3).

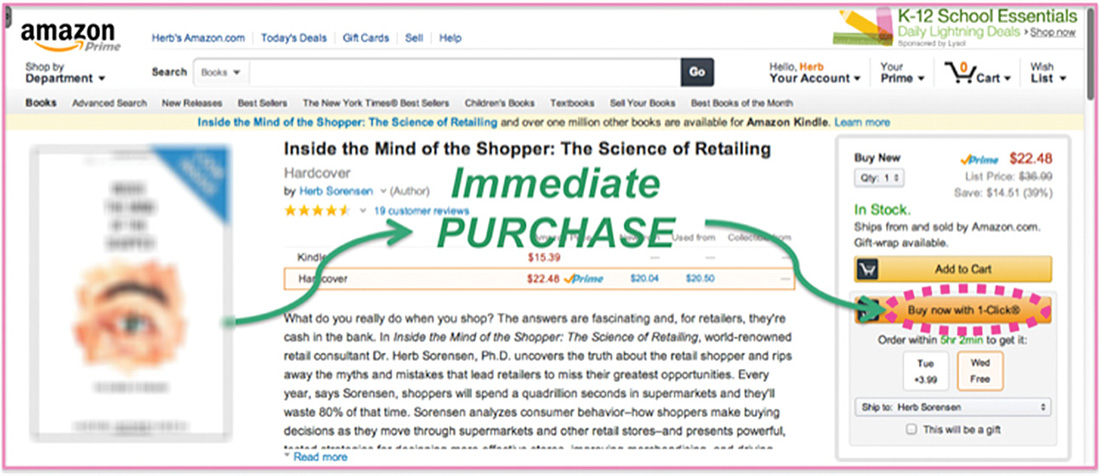

Amazon Focus #2: Immediate Close

A few specific features of this page teach us how Amazon handles this customer. First, Amazon offers an immediate close of the sale with subsequent delivery of the physical merchandise. Notice that the instant there is a meeting of the minds. (Amazon agrees to sell; shopper agrees to buy.) Amazon wants to consummate the sale with the immediate convenience of the 1-Click option (Figure 3.4). This follows the supreme dictum of personal selling, which states “Close early and close often.”

Figure 3.4 A real salesman immediately seeks to complete the sale, not as a matter of pressure, but as a convenience!

Notice the urgency of Amazon in securing the sale. This kind of urgency demonstrates what Greg Linden noted above. This is the next book you want to buy. This issue is of such importance to Amazon that they patented their 1-Click purchase method. Rather than just putting the book in the cart, Amazon encourages the shopper to buy it immediately. Lots of sales are lost online through the abandoned shopping cart. In the bricks store, products do not even make it to the shopping cart. Shoppers simply abandon any consideration of the product.

Amazon Focus #3: Affinity Sales and Crowd-Social Marketing

Summarizing to this point, the shopper entered a search (first click), clicked on the likely desired book (second click), and purchased the book with another click (third click). 1-2-3, the deal is done! But Amazon is not done. It will, subsequent to the close, or if the shopper did not purchase, attempt to make another sale immediately on the heels of the first or as an alternate to the first offer.

Moving down the page, on the left, as the eye naturally moves, Amazon introduces books closely related to Inside the Mind of the Shopper. With this effort, Amazon is still trying to sell the original offer because the shopper continues to have an interest in the book on which they initially clicked. But the shopper is not yet ready to close the sale (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 And a real salesman never stops selling: If a sale is made, maybe an add-on; if not, still seek to fill the need with something related.

So Amazon leverages two powerful selling strategies: affinity marketing (what goes well with this) and crowd-social marketing (what other shoppers have done).

These two techniques are closely related but with alternate motivations. For example, you might not think of purchasing ham and eggs together. But the reality is that large numbers of people do buy them together. So a good salesman could employ affinity marketing and suggest that you buy them together based on their inherent, complimentary properties. Ham goes well with eggs. Or she might use crowd-social marketing and suggest you purchase them together because lots of other shoppers have bought both ham and eggs and were happy with the results.

Robert Cialdini refers to this as the Principle of Social Proof: “We determine what is correct by finding out what other people think is correct.”3 In this case, the people who buy Paco Underhill’s book4 and Robin Lewis’s book5 also buy Sorensen’s book. Therefore, the correct thing for the shopper to do is to buy Sorensen’s book. This very clever use of crowd-social marketing is also nudging sales of Underhill’s and Lewis’s books, too, if the shopper hasn’t already bought them.

Amazon Focus #4: Reaching into the Long Tail

Let’s return to your initial search while shopping science books. You have not added Inside the Mind of the Shopper to your shopping cart or clicked the instant-purchase option. Just because the close hasn’t happened yet is no reason to give up on the sale. Amazon is leading your mind into deeper and deeper consideration of the offer. Of course, Amazon would have liked to close the sale immediately, but you may be a maximizer. Barry Schwartz in The Paradox of Choice, points out that people tend to fall into one of two camps. The maximizer is always concerned that there may be a better choice, and is willing to spend considerable effort in maximizing their selection. The satisficer, on the other hand, operates with some, possibly subconscious, measure of suitability, and when that is achieved, is happy to buy without second thoughts about whether there might have been some better alternate choice.6

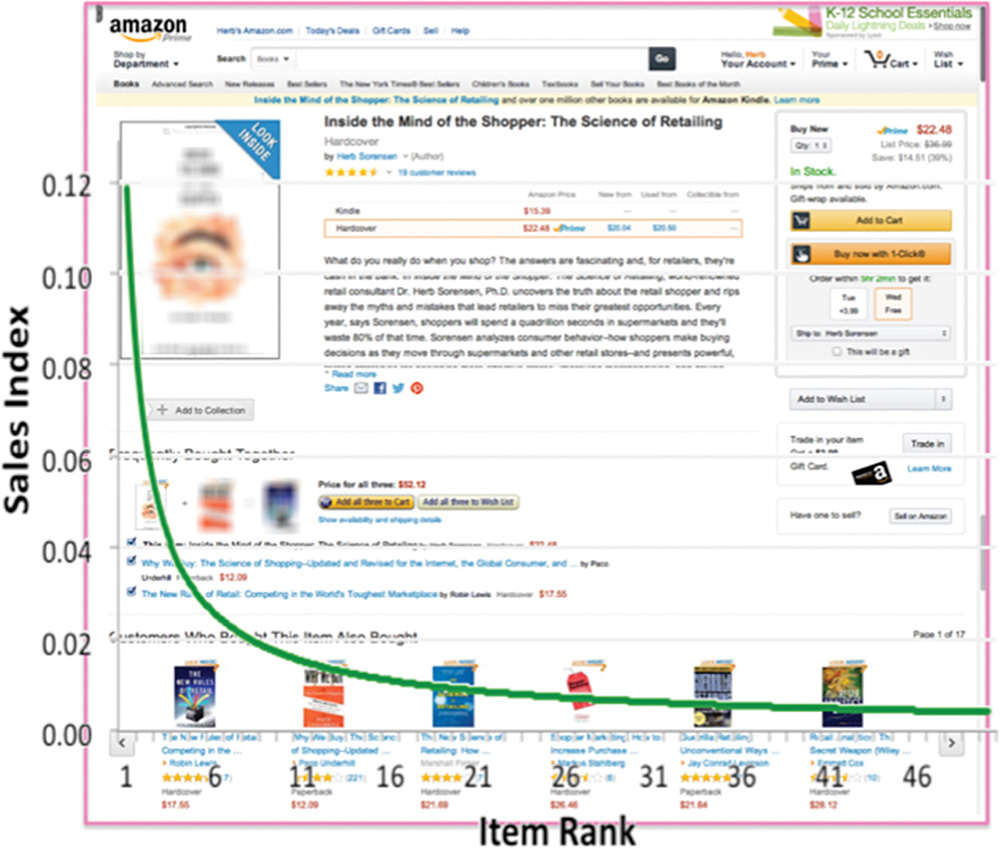

Ideally, the shopper would have closed with the first 1-2-3 offer, but we can afford to be patient, especially because this is Amazon and “we” are really an algorithm, mediating the sale to the shopper. We can afford to be patient, matching the shopper’s every time expenditure with additional appropriate selling. In this case of a maximizer, the appropriate selling is a multiplication of choices, a reaching into the Long Tail (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6 A large number of “related” items can be offered sequentially—all the way into a very long tail!

I placed a Big Head/Long Tail graph over this Amazon web page to show you how, after the search, immediate offer, and social offer, the next step is to dip a bit further into the Long Tail. This is illustrated by a sliding scale of about 100 books, shown eight at a time, that “Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought.” This puts the book that the shopper is still considering and has on their screen (top-left corner), in the expanded affinity and social context of other items that they might be interested in.

Amazon Focus #5: Info, Info, Info

From this point on down the Amazon page, the dominant theme is reviews, further rankings, biographical information, and links to other material that may be useful to the shopper. In fact, Amazon is one encyclopedic source of curated information about published knowledge, insight, and opinion that can be scanned at high or low levels to assess what leaders in any field are thinking about, and how other readers react to that thinking. People actually use bricks stores in this same way, to a limited extent.

The five selection foci listed above have direct counterparts, though perhaps not as obvious, in the bricks stores. But these five points define how Amazon meets the minds of its shoppers. Combine this with Amazonian delivery (logistics) and payment (money) and you have the winning global retailer in bricks stores a decade or two hence. But recognizing the store as a communal pantry, or bookshelf, or closet, or whatever, the winning global retailer will be a bricks retailer, possibly an Amazonian hybrid.

Amazonian Selling in Bricks Stores

A couple of concepts are essential in applying Amazonian techniques to bricks selling. The first of these concepts is that there is a lot less diversity in the shopping crowd than is on exhibit in the offers of self-service retail stores. Out of the 40,000 SKUs in the typical supermarket, most families buy only 150–200 different SKUs on a regular basis. We might then call the first principle “The focus of the individual.”

The second principle is that the purchases of any randomly selected crowd of 10,000 people will have an amazing similarity to the purchases of any other 10,000 people. We might call this second principle “The constancy of the crowd.” This is what makes it possible for a store with 2,000 SKUs to achieve $100 million in annual sales. Relating individual behavior to the crowd and the crowd’s behavior to the individual is the key principle that allows intelligent relation of Amazonian selling (knowledge of the individual) to bricks-and-mortar selling (crowd knowledge—without smart phones).

But notice how Amazon’s 50 million books attract shoppers who want to buy only one, in the same way the 40,000 SKUs in a supermarket attract shoppers who are most likely wanting to buy five. This attractive property is why any store with 40,000 SKUs should sell at least as much as the store with 2,000 SKUs. Amazon would use those extra 38,000 SKUs to attract more shoppers. But in fact, most stores have the advantage of that attractiveness and then unwittingly squander it by impeding the shopping inside their stores. Burying what the shopper wants in an indiscriminate sea of attractiveness is a great sales suppressing device that developed naturally as a consequence of self-service 100 years ago.

Let’s think about how Amazon might manage the two basic issues of selling in a bricks store. Remember, these are navigation, getting the customer and the merchandise together; and selection, closing the sale by getting the shopper to accept the offer.

Amazonian Bricks Focus #1: Navigation—Simple and Fast

Before discussing how to assist shoppers in quickly selecting their desired purchase, let’s first discuss how to best impede them in that task. This helps us understand how sales suppression occurs in store aisles. Knowing this will make more obvious what we need to do to remove the impediment.

Of course, Amazon has an advantage in that a targeted search online can lead to the desired location in a click or two. But the Amazon shopper can also flee their store in a click or two, so it isn’t all advantage Amazon.

Another advantage of the bricks store is the visual advantage. Recall that in the selling process a major connector between the retailer and the shopper is vision. The bricks store has visual advantages with the shopper’s eye taking in the store’s offerings in more than 1,000 distinct points of focus over a mammoth screen, 25% of the whole store in a 10 minute shopping trip. Ten minutes online represent a comparable number of points of focus, with a far more narrow, more focused, field of vision. The bricks store has a much longer tail of visual experience, whereas the online store has a longer tail of merchandise. But therein lies the rub: that rich visual experience in the bricks store invites a lack of focus that is far more easily managed on a computer screen. But, it is possible for the bricks store to have a far richer, more varied field of vision and still retain essential focus and targeting.

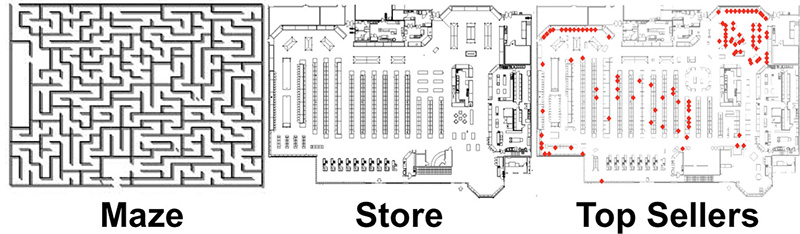

So, how to impede shopper navigation? Let’s begin with perhaps the worst possible navigational system (Figure 3.7):

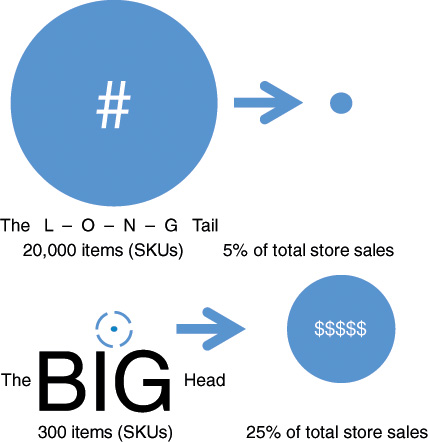

On the left, you have the extreme design of the maze, the worst possible navigation system. This is not an absurd approximation of an actual bricks store (center). Then, on the right, you see the actual locations the top 80 items that shoppers want most out of the tens of thousands of items on the store’s shelves. These 80 items are the tip of the Big Head, so called because it generates big sales and profits. On the other hand, half of those tens of thousands of items, 20,000, generate about 5% of the store’s sales. These 20,000 are the tailing end of the Long Tail. Large numbers of these items don’t sell a single copy in a month, and quite a few, not in an entire year. The top 300 items constitute about 25% of total store sales. To really sell a lot, we need to understand the factors that drive not selling a lot (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8 A tiny number of products are mostly what shoppers want; most other products do attract shoppers to the store—where they mostly buy from the few!

Large numbers of those items, like Amazon’s 50 million books, do a great job of attracting shoppers to the store. But those items present a challenge to both navigation and selection. For navigation, the large selection virtually requires that a substantial amount of the store be devoted to a maze like, quasi-warehouse structure where shoppers serve themselves as stock-pickers (Figure 3.9).

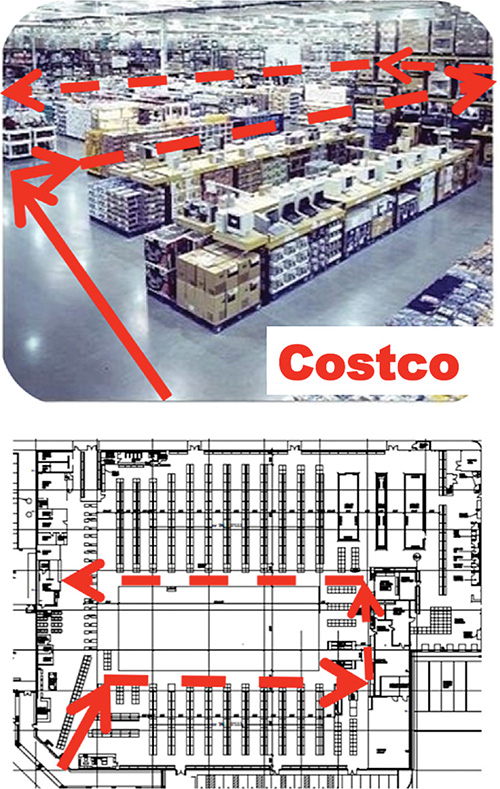

Figure 3.9 The rapidly growing number-two global retailer uses the convenient dominant U-turn path for most of its selling. (The struggling number-one retailer sticks with the maze, “warehouse” design.)

To achieve Amazonian navigation in the bricks stores, the retailer must make lots of choices for the shopper, beginning with where they go in the store. The need for focus demands that the shopper’s path be limited. It may be possible for the retailer to create two or three intuitive, instinctive, and distinctive paths. But designing the store with a single, Dominant Path, which the majority of shoppers in the store use, is the retailer’s way of guiding the shoppers on an efficient path.

The Costco path really is intuitive, instinctive, and distinctive. I didn’t notice it myself until I actually measured shoppers’ experiences in the store. Costco also has a substantial Long Tail, which is visible to shoppers in the warehouse shelves on the outer perimeter of the store, or low table displays across the interior of the U-turn. Both are readily visible from the single dominant U-turn path, with plenty of opportunities for the shopper to listen to the siren call of the Long Tail (Figure 3.10). Any shopper, at any time, may turn off the Dominant Path to sate their interest in Long Tail.

Figure 3.10 Shoppers are not forced into the dominant U-turn, but enter on the front of the store at the right, and are naturally attracted to the convenience of the W – I – D – E aisle around the store!

An important consequence of the single Dominant Path is that it allows Costco to deal with the shopping trip as a process. It creates an orderly series of offers and acceptances, just as if personal salesmen were meeting the shoppers at strategic points along their trip and selling to them. It is not the merchant warehouseman’s system of stacking the products on shelves and hoping the shopper can find what they want and need. This plays a role in the Amazonian selection assistance, too. Simple in-store navigation is part of the reason Costco is a growing international player, now number two globally7 behind Walmart.

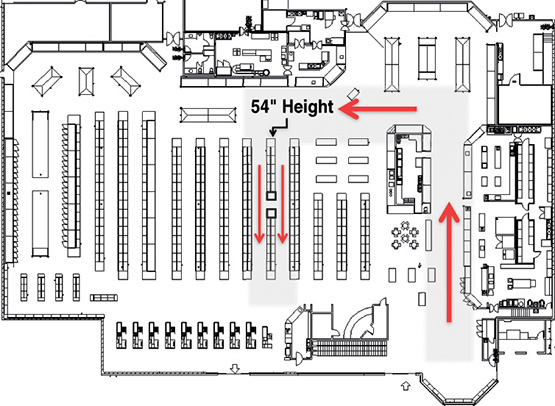

You don’t have to rebuild the store in order to provide a dominant single path. Nearly any maze-like store can introduce a Dominant Path with minimal fixture alteration. Most stores already have a wide aisle to the back and a wide aisle across the back. Lower one gondola from the back to the front of the store to a height of four or five feet, and put one or two cut-throughs in it. This creates a close enough facsimile of a single aisle about 20 feet wide, given usual aisle and gondola widths. It has the advantage of adding two or more endcaps and a large increase of visual exposure to all the merchandise displayed in what is effectively a compound aisle (Figure 3.11). More cut-throughs equal more endcaps, an important tool for focus.

In the example here, the store already had a wide aisle past floral and through the bakery and deli departments, leading to produce and then the fresh meat/poultry/seafood across from fine wines. This gets us to the return to the front, usually at the first checkouts to be seen from the back on the shopper’s left. This is how you get Amazonian navigation into the supermarket—or any other store.

Summarizing the Amazonian navigation principles in bricks stores:

1. Provide a single Dominant Path to, and past, the merchandise most desired by the shoppers—the Big Head.

2. Maintain visual openness to the rest of the store, and specifically to the large array of merchandise that is attracting shoppers to the store, even if sales of those Long Tail items are more limited.

Admittedly, Amazonian navigation seems a bit more complex in a bricks store than it does using the bits and bytes of online navigation. But the principle is the same in both: get the shopper to the merchandise they are most likely to buy quickly and expeditiously, emphasis on the most likely to buy. Meanwhile, provide ready access to the Long Tail, without muddying the efficient choices from the Big Head.

Amazonian Bricks Focus: Selection

Previously we addressed the issue of getting the shoppers to the merchandise they want. Now, we address how the bricks Amazonian personal salesman, acting as a ghost in the aisle, assists the shopper in selecting the product they want, focusing on small numbers of options, mostly from the Big Head. The proper strategy is to use crowd statistics to relate to every shopper in the store individually. At each point on the trip, ask yourself “What will the crowd want?” The answer will be found in the transaction logs for the store.

Amazonian Bricks Focus #2: Immediate Close

We turn our attention first to the single Dominant Path, where most of the sales occur. Begin with a guiding principle set forth by Joe Girard, the world’s greatest salesman, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. In his own words:

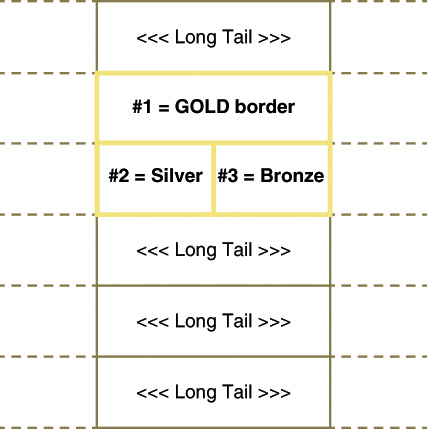

“Over the years, I have discovered that the more choices presented to prospects [shoppers], the more difficult it becomes for them to make up their minds. While I don't have concrete evidence backed by formal research, I have observed that when people have to choose from more than three choices, they have a hard time determining which to pick . . . I recommend offering a maximum of three.”8

Recall how our navigation of Amazon began in the previous section. We entered a search term and it showed us a ranked list of everything matching that search beginning with the top sellers. Your first step in navigation is to select one thing from that list of greatest interest to you. And moving from navigation to selection, if you don’t immediately buy the item on which you first clicked, it offers you two or three options.

In the bricks store, the Amazonian salesman, as a ghost in the aisle, offers you the item you are most likely to buy in the immediate area wherever you happen to be in the store. For the vast majority of purchases, that should be on the Dominant Path. Now, where in the supermarket do you expect to find choices of three? The only places to consistently offer only a few items for choice are the endcap displays. And what does Costco have lining the right side of that single dominant aisle? Of course, it is a series of 37 endcaps, most with one, two, or maybe a few items.

The “top seller” is always in the context of what is being sold. Amazon has top sellers in thousands of categories. But it only touts the ones in the category where the shopper is browsing right now, as indicated by their click stream leading up to the current screen. Translating this to the bricks store means that some type of distinctive Top Seller tag for specific items in each department is probably appropriate. Although I have ideas on this subject, at the time of publication I have not conducted conclusive research in this area.

Amazon is not trying to sell the shopper what Amazon has in stock; it sells the shopper what the shopper wants. We repeat this distinction because it is so crucial. Amazon does not care what you buy, they will sell you anything they have that you want. This is true customer-centricity.

For the supermarket, think about the 300 items that will constitute 25% of store sales. It is a lot easier to figure out how to sell 300 items to the shopper rather than the 40,000 in the store. Let’s begin by putting those 300 items on the Dominant Path, instead of scattering them around the store and burying them among the remaining 39,700 items of little to no interest to the shopper. Just as Amazon focuses the shopper by offering a small selection of its millions of products based on the shopper’s search and ranking that selection according to which ones the shopper is most likely to buy, the bricks Amazonian retailer helps the shopper focus by placing the 300 items they are most likely to purchase on the single, wide, navigable, visible Dominant Path.

Two Closing Techniques

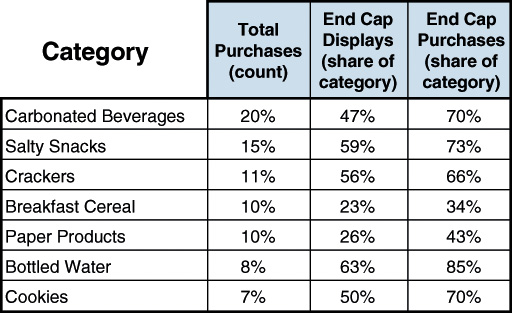

The immediate close in the supermarket is heavily focused on two techniques, the first of which is endcaps. That is because endcaps often have only three items on them, automatically creating Joe Girard’s offering of three. Figure 3.12 shows some examples of top category performers on endcaps:

The Total Purchases column is based not on dollars, but on the number of purchase events in the category—essentially distinct items purchased, by count, not by dollar. The second column, End Cap Displays, shows the share of promotional displays for that category, typically endcaps, but also freestanding aisle displays and others, across 13 stores for over a million shoppers. The third column, End Cap Purchases, shows the share of category purchases, by count, on the endcaps. Across these significant endcap performers, the average sales per display is 1.4 times the average purchases, 40% more than from main aisle displays counting each 4-foot aisle section as one display.

This average 40% lift is not due to price discounting. Glenn Terbeek9 showed that only 25% of shoppers from a price discounted endcap were actually influenced by the price. Endcaps are an excellent sales tool, and their selling is primarily due to their focus on a limited selection.10 Note that some top-tier global retailers regularly use promotional endcaps without any reduction in price. This does not mean that a low price image is not of any value. But the efficiency gains from everyday low prices (EDLP) can be passed on to shoppers for genuine savings.

All 300 Big Head items should be represented in the Dominant Path that we illustrate above. This does not mean that entire categories need to be moved here. For example, it is highly effective to use one of the refrigerated cases on this path to display a small selection of the best quality, highest margin dairy items. Do not lower the prices. The promotion is the location, not the price, and shoppers will gladly give you the extra margin for meeting their needs more efficiently. The full dairy department located elsewhere in the store will meet Long Tail needs.

The second technique involves not just making it convenient to reach the top seller items, but calling out and focusing attention on the single highest top seller. This is not a matter of selling that designation to the highest bidder amongst the brand suppliers. There are plenty of well justified opportunities for that, but not mixed and confounded with the shoppers’ own choices. By highlighting the top seller, you leverage the same kind of crowd-social marketing that Amazon utilizes when it shows its shoppers the number one best seller. In the sense that you are calling attention to what most of the crowd buys from the options on display. Note that Amazon’s online selling strategy would crumble if they allowed suppliers to buy the top ranking. They might make some short term profit gains, but if consistently practiced, they would erode a huge advantage they have against bricks retailers: Customers have come to trust Amazon’s rankings.

Amazonian Bricks Focus #3: Affinity Sales/Crowd-Social Marketing

There is nothing wrong with offering a second or third option beside the top seller. There are several types of products that you can use to encourage purchase of the top seller. The first of these is affinity sales. What goes well with this item? The answer to that question requires no special culinary insight or marketing genius. When shoppers buy this specific item, what other items do they buy associated with it? Recall our discussion on ham and eggs earlier in this chapter.

The answer to this question requires a careful statistical analysis of the transaction log to verify that if shoppers buy item A, they are most likely to also buy item N. Sometimes the reason for the affinity is obvious. This is why can openers are often sold in canned pet food aisles. But we have to be realistic about the ability of bricks retailers to move items around, which is not virtually effortless as it is in Amazon’s case. This means that affinities are more appropriately dealt with as adjacencies in bricks stores, and are better handled by categories than by individual items.

However, there is one affinity strategy that may be especially appropriate for store brand products. Consider the pie crust example in Figure 3.13.

Figure 3.13 Creating a “value” image for the store, while still selling more of high dollar product!

Notice that the store brand, Shoppers’ Savings $, is priced 40% less at $2.49 versus $4.19 for the Shoppers’ Choice, #1. In this case, we are calling the shopper’s attention to the fact that there is a way to save significant money here. There is no reason to expect to divert shoppers from the proven number-one choice. The purpose is to tell the shopper, “Hey, if you are squeezing every penny, look no further, the best price is right here.” The strategy is not to sell the alternate but to represent that this store has got your back, if you really need to save money. But it’s not surprising that people will spend the extra $1.70 for the Pillsbury product. Amazon uses this same strategy at a much lower level by giving you the opportunity to rank a selection of products by price rather than by bestsellers.

Remember, the price tells you two things: how much you will have to pay for this item, and also, how much this item is worth. Studies have shown that shoppers will buy more of the exact same item if you raise the price. I know that seems counterintuitive, but the shopper’s intuition is that maybe it’s cheaper because it isn’t as good. The image of price fairness is more important than the price. And maybe a pie that you are going to bake yourself is worth the extra $1.70 for a premium crust.

In a store with 40,000 SKUs, calling out the 50 or100 true top sellers selected from the top few hundred SKUs will generate significant lift for the entire store. Backing this up with affinity sales, carefully considered category adjacencies, sharpens shopper focus and provides a one-two punch for the most productive part of the store: the Dominant Path.

Amazonian Bricks Focus #4: Reaching into the Long Tail

As attractive as the Long Tail is, it should be seen and not heard. The challenge is to maintain the pull of the Long Tail without dampening the natural push of the Big Head. Remember, the Big Head consists of what the shoppers want to buy. Don’t let the Long Tail get in the way.

Conceptually, we can solve this problem by maintaining the Big Head in a selling space while keeping the Long Tail in a warehouse space. Most retailers already have approximated these two spaces by designing stores with a wide open perimeter surrounding a narrow-aisled center-of-store warehouse. Unfortunately, many Big Head items are buried in that center-of-store warehouse and there are plenty of Long Tail items on display around the perimeter selling area. The bigger problem of the two is burying Big Head items anywhere.

The key then is making the warehouse space visually present in a maximum way. Costco has done this by leaving a very large warehouse space that rises to the ceiling all around the outer wall of the building. They knocked the center-of-store space, also a lot of Long Tail area, down to under four feet in height, giving great visual access even to the far wall of perimeter merchandise and visual openness comparable to the top-selling produce areas in typical supermarkets. Costco has an off-the-path, large, bazaar-like fresh food and produce area in a far corner of the store, but it maintains the openness through a very large percentage of the store. This combines two attractive properties for maximum use: the Long Tail attracts, somewhat indiscriminately; open space attracts, again somewhat indiscriminately.

Amazonian Bricks Focus #5: Info, Info, Info

Notice where Amazon puts the great bulk of their product information: at the bottom of the page, out of sight and out of mind, unless you scroll down to see it. You can think of information like the Long Tail, to be seen but not heard, unless you need it. The vast majority of information available to shoppers in the stores is already on the package. Providing information kiosks, brochures, short video clips, and other informative media can be helpful if it doesn’t get in the way of Big Head sales. Nothing should distract the shopper from the convenience and efficiency of speedy selection from the Big Head.

Review Questions

1. Describe the function in retail called meeting of the minds. How does this function usually occur in self-service retail? How does Amazon facilitate this function through its online store? What advantage do online stores have? What about bricks stores?

2. How does Amazon assist shopper navigation? What is their mechanism replacing the salesperson service? How can self-service bricks retailers apply these techniques?

3. Describe how Amazon uses affinity sales. How do these techniques relate to the concept of personal selling or mediated sales? How can self-service bricks retailers utilize these tools (think of the challenge of Long Tail)? How can a retailer decide what goes with what on a shelf?

4. How does Amazon manage the Long Tail in their bricks store? How does this compare to the concepts of the Dominant Path and the Dark Store?

5. Describe how individual shopper behavior relates to crowd behavior and how the use of numbers, metrics, and crowd statistics makes it possible to predict future sales for the majority of shoppers.

6. Consider Costco’s layout. What makes its layout a good example of a store with clear Dominant Path? How do shoppers access the Long Tail in a Costco store?

7. What simple changes in a typical bricks store could deliver visual openness to the Dominant Path and the merchandise?

8. The paradox of choice suggests that too much choice might confuse shoppers. Which shelf spaces and displays in a bricks store could be used for a limited selection offer? Why would they be suitable for this task?

Endnotes

1. Fader, Peter, Moe, Wendy, “Integrating Online and Offline Retailing,” Chapter 4 of Inside the Mind of the Shopper (Sorensen) 2nd Edition.

2. Brandt, Richard L. (2011). One Click: Jeff Bezos and the Rise of Amazon.com. New York, New York: Penguin Group.

3. Influence: Science and Practice (http://www.amazon.com/Influence-Practice-Robert-B-Cialdini/dp/0205609996?ie=UTF8&keywords=cialdini%20influence&qid=1376787837&ref_=sr_1_2&s=books&sr=1-2)

4. Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping—Updated and Revised for the Internet, the Global Consumer, and Beyond (http://www.amazon.com/Why-We-Buy-Shopping-Updated-Internet/dp/1416595244?ie=UTF8&ref_=pd_bxgy_b_text_y)

5. The New Rules of Retail: Competing in the World's Toughest Marketplace (http://www.amazon.com/New-Rules-Retail-Competing-Marketplace/dp/0230105726?ie=UTF8&ref_=pd_bxgy_b_text_z)

6. Schwartz, Barry (2009). The Paradox of Choice. New York, New York. HarperCollins.

7. Gaul, Ray, “Top 50 Global Retailers,” Chain Store Age magazine, vol. 89, no. 6, October 2013.

8. See: “Choices of Three” in “How to Close Every Sale” (Commentary on Joe Girard's book) http://www.shopperscientist.com/2011-10-06.html

9. Terbeek, Glen A. (1999). Agentry Agenda: Selling Food in a Frictionless Marketplace. Chesterfield, VA: American Book Company.

10. See also, Anderson, Eric and Duncan Simester, “Mind Your Pricing Cues,” (http://classes.bus.oregonstate.edu/winter-06/ba499/elton/Articles/Mind%20Your%20Pricing%20Cues.pdf) and “No, the Customer is NOT Always Right!.” http://www.shopperscientist.com/2009-07-23.html