10. Brands, Retailers, and Shoppers: Why the Long Tail Is Wagging the Dog

“Whenever an individual or business decides that success has been attained, progress stops.”

—Thomas J. Watson, founder of IBM

There is a famous story about when Tesco started trials of its loyalty card, Clubcard, in the mid-90s. The retailer called on the services of dunnhumby, a company specializing in data analysis. The results of these first trials were delivered to the Tesco board in November 1994—which led to a prolonged and awkward silence.

The board chewed over a 30-minute presentation about customer response rates, the impact on like-for-like sales, and a dazzling array of data collected from 14 stores. It was Sir Ian McLaurin, then Tesco chairman, who broke the silence with a now apocryphal remark. “What scares me,” he said, “is that you know more about my customers after just three months than I do after 30 years.”1

It might seem odd that a very successful retailer would know so little about its customers or what they do while shopping. Tesco and other retailers obviously are increasing their understanding of shoppers (although loyalty cards just tell what happens at the checkout, not in the store). In many ways, the massive problems in this industry are caused by everyone assuming that supermarket managements are the repositories of deep insight into the shopping process. By and large, they are not. There are a few exceptions—but they prove the rule.

There is a reason why retailers have historically paid so little attention to their shoppers—they are not rewarded for doing so. The economics of retailing are completely biased against it. We cannot explore the mind of the shopper without expanding our view to look at the broader—and shifting—relationship between retailers and the manufacturers of brands on their shelves. This complex and uneasy relationship helps explain much of what may appear to be counterintuitive about how retailers work. Understanding this relationship also highlights opportunities, which we discuss in this chapter, for brand owners and retailers to collaborate more effectively in selling products. Brand owners can help retailers redesign their stores to maximize sales and can also take advantage of powerful merchandising promotional planning programs to pitch the emotional messaging of each category more precisely.

Where the Money Is in Retail

If shoppers are ignored, it is because they contribute the least to retailers’ bottom lines. This may be surprising, because on the surface the entire business model of a retailer seems to be to sell products to shoppers. But a closer look shows that this is only a front for the true business. The main sources of supermarket profits are, in order of importance:

![]() Trade and promotional allowances from the brand suppliers: The number-one source of profits consists of rebates of one variety or another from those manufacturers who want to “warehouse” their merchandise in the retailer’s self-service stores. The sometimes-maligned slotting fees are, in reality, a rational warehouse operator’s recovery of storage costs from those who want to take the available space. It has been noted that supermarkets make their money by buying (from the supplier), not by selling (to the shopper).

Trade and promotional allowances from the brand suppliers: The number-one source of profits consists of rebates of one variety or another from those manufacturers who want to “warehouse” their merchandise in the retailer’s self-service stores. The sometimes-maligned slotting fees are, in reality, a rational warehouse operator’s recovery of storage costs from those who want to take the available space. It has been noted that supermarkets make their money by buying (from the supplier), not by selling (to the shopper).

![]() Float on cash: Stores necessarily manage very large amounts of cash. In fact, one executive pointed out to the author the large amount of “abuse” the store receives from shoppers, but then pointed out that this is compensated for by the fact that they leave “their cash on the counter.” This cash is hurried to the bank to begin immediately accruing interest, or float. Float will multiply until the necessities of business require the dispersal of cash to suppliers, employees, and others, days, if not weeks later. In any event, the store wants to begin instantly accruing interest on its portion of that $15 trillion annual turnover of the retail industry. A few seconds of that interest would suffice to maintain most households for decades. This is the second major source of profits.

Float on cash: Stores necessarily manage very large amounts of cash. In fact, one executive pointed out to the author the large amount of “abuse” the store receives from shoppers, but then pointed out that this is compensated for by the fact that they leave “their cash on the counter.” This cash is hurried to the bank to begin immediately accruing interest, or float. Float will multiply until the necessities of business require the dispersal of cash to suppliers, employees, and others, days, if not weeks later. In any event, the store wants to begin instantly accruing interest on its portion of that $15 trillion annual turnover of the retail industry. A few seconds of that interest would suffice to maintain most households for decades. This is the second major source of profits.

![]() Real estate: Every major chain maintains a large real estate department that finds real estate to develop for stores, often in developing communities. In a few years, that developed real estate will likely be worth multiples of the initial investment—not carried on the books as profit, because it will be unrealized until the sale of the property itself—often decades later after the underlying business has paid for it many times over.

Real estate: Every major chain maintains a large real estate department that finds real estate to develop for stores, often in developing communities. In a few years, that developed real estate will likely be worth multiples of the initial investment—not carried on the books as profit, because it will be unrealized until the sale of the property itself—often decades later after the underlying business has paid for it many times over.

![]() Margin on sales: This fourth source is not to be sneezed at, largely consisting of service departments, operated on the retailers’ own prime in-store real estate—the wide perimeter zones or other high-traffic areas. This includes things like the meat department, in-store deli, pharmacies, and so on. Another growing area of profit is contract outsourcing, where outside suppliers manage certain aspects of the operation (such as cafes/restaurants or flowers) and the retailers get a share of the margin from the contractor.

Margin on sales: This fourth source is not to be sneezed at, largely consisting of service departments, operated on the retailers’ own prime in-store real estate—the wide perimeter zones or other high-traffic areas. This includes things like the meat department, in-store deli, pharmacies, and so on. Another growing area of profit is contract outsourcing, where outside suppliers manage certain aspects of the operation (such as cafes/restaurants or flowers) and the retailers get a share of the margin from the contractor.

When these sources of profit, and the inherent nature of self-service or passive retailing, are made clear, it is not surprising that retailers don’t know a lot about the actual behavior of the shoppers in their stores. Why should they? The shoppers have been assigned responsibility for their own shopping-essentially, unpaid stock pickers, and they aren’t really complaining. But this is a dangerous and complacent position for retailers to be in because this passive methodology is increasingly being strained by the diminishing effectiveness of outside-the-store communication.

The reason the Long Tail is wagging the dog in retail is that brand owners are investing in promoting their many products in the Long Tail. As long as manufacturers are putting up the money, it makes sense for retailers to keep their large warehouses well stocked. But if shoppers are buying largely from the Big Head store, could retailers and manufacturers work more effectively in meeting this need?

Massive Amounts of Data

In addition to this economic imperative, there is another major factor driving the lack of interest in what is going on inside the store. That is the massive amount of information about what is coming out of the store, or the veritable flood of data spewing out of the scanners around the world. This scan data has spawned two major industries in their own right: compilers and resellers of the categorized data—Nielsen and IRI being the preeminent examples—and the advanced analytics relating this data to specific shoppers through the use of loyalty card programs, demonstrated by dunnhumby and related businesses.

As positive as these derivative businesses are, neither speaks well of the retailers’ own understanding of the shopping process. First, for decades, electronic barcode scanners contributed little more than an expedited method for ringing up the shoppers’ purchases. Of course, sales data was more reliable for inventory control than the older warehouse velocity measures such as those provided by SAMI, which measured movements of goods based on warehouse withdrawals to the stores. But pricing and inventory control hardly bathe the retailer in glory for its use of shopper insights.

In fact, the salutary effect of dunnhumby on Tesco only serves to highlight the deficiency of the retail giant’s previous approach to the business. And now there is an ever-growing cadre of dunnhumby-type firms who are surely accelerating business and profits for any number of retailers through advanced analytics of the scan data linked to the loyalty cards of individual, specific shoppers. So just imagine the impact on profits of going even further and measuring what is going on in the actual shopping process in the store.

This is the stark reality that drives a good deal of retailing. It’s not that retailers and suppliers don’t seek to have a relationship with shoppers, but that their own mutual relationship tends to cause those to the shoppers to pale into insignificance, and, as a result, to remain somewhat distant by comparison. This is the reality of the self-service, warehouse-based view of the store. Sometimes my views may seem too critical, but there are certain absurdities in the industry that are driven by the economic structure. In the U.S. alone, fully one trillion dollars is paid by brand suppliers for the supermarkets to manage their supermarkets in a certain way.

To me, this is the emperor with no clothes. This is why supermarket managers measure inputs and outputs of the store but are largely blind to the process occurring in the store. And this blindness is shared by their brand suppliers. It is essentially the $1 trillion that the brands are paying retailers that justifies their leaving the $80 million per store on the table through not understanding and serving shoppers better. Of course, we have no illusions that there really is, in aggregate, an extra $80 million per store available to every store. But exceptions such as Stew Leonard’s, with its $100 million stores, show that much more is possible, for any individual store.

Shifting Relationships

The relationship between manufacturers and retailers is already shifting with the rise of private-label brands and the increasing marketing sophistication of retailers. In an October 2008 article in Advertising Age, Jack Neff reported how retailers are hiring talent away from consumer goods companies, measuring shoppers, and building their own brands—“raising big questions about the balance of power in the industry.”2 Retailers are increasingly focused on building their own brands rather than turning over their stores to manufacturers. This is neither good nor news to the brands. However, the role of brands is often not well understood or represented at retail. It helps to consider that when shoppers purchase branded items, they are acquiring three distinct values:

![]() Intrinsic value: A carbonated beverage will quench your thirst and meet your physiologic need for water.

Intrinsic value: A carbonated beverage will quench your thirst and meet your physiologic need for water.

![]() Added value: Packaging the beverage and delivering it to you in a convenient, and possibly chilled, form adds value to the intrinsic value of the water.

Added value: Packaging the beverage and delivering it to you in a convenient, and possibly chilled, form adds value to the intrinsic value of the water.

![]() Creative value: This third value is in the mind of the shopper and is the essence of brand value.

Creative value: This third value is in the mind of the shopper and is the essence of brand value.

Because this third, creative value sometimes seems to be a gossamer wisp, it tends to be misunderstood and abused. It obviously has considerable commercial value, because all profits derive from the difference between costs and prices. The cost of intrinsic value is properly regulated by competition for basic, commodity resources. The cost of added value depends on manufacturing and distribution efficiency, including such things as cleverness of design. So what is the cost of creative value? Unit cost is zero, because once created, there is no additional cost, the more of it is sold.

Once created, creative value is a bountiful source of profits. This is its strength and its vulnerability. The vulnerability is because those who do not own the brand are probably unwilling, at some level, to pay for it. This is the reason brands spend so much time and effort trying to convince the market that their value is really intrinsic or added. There is nothing wrong with a better mousetrap, and part of the value of the brand is the assurance that the brand will provide the “better” product.

But whether designer jeans or bananas, there is that something about the brand that makes a customer feel very good about spending a few pennies—or more than a few dollars—for it. In fact, that additional creative value is an important part of accelerating the upward growth of society. Think of that creative value as aspirational, something in the soul that longs for improvement and betterment.

In times of economic distress, there is always a call for a retreat to only intrinsic and added value. Retailers’ first ventures in competing with their brand suppliers historically involved offering intrinsic plus added value private-label products only. The cutting edge today in retailing, however, is heavily dependent on building strong own-label brands, far removed from the old white label generics, as can be seen in retailers such as Trader Joe’s. This is shifting the balance of power in retailing and placing more emphasis on understanding how shoppers interact with brands in the store.

Although retailers have learned how to create brands (creative value), they have long assaulted the concept of brands by insisting on cutting prices to promote them. This strategy suggests to customers that brands were overpriced at their regular retail prices. Although the relationship between the manufacturer and retailer is often seen as a great struggle over the value created from shopping, this does not have to be the case. In fact, as we consider next, both retailers and brand owners can often do better if they work together to serve the shopper better.

A Refreshing Change: Working Together to Sweeten Sales

Assuming that both retailers and manufacturers want to sell products to consumers, if they understand shoppers better, they can work together more effectively to use in-store marketing in more sophisticated ways. ID Magasin, for example, worked with chewing gum manufacturer Dandy, a business unit of confectionery giant Cadbury-Schweppes, to increase category sales by as much as 40% by introducing “refreshment cues” in the pre-checkout area of Swiss retailer Pilatus Markt.

In-store research in 2001 examined how shoppers interacted with chewing gum displays at the checkouts. The company filmed, interviewed, and counted thousands of shoppers at three checkouts, each of which was merchandised differently to enable comparison of different concepts. Representative customers were also fitted with a point-of-focus/eye mark recorder to identify the visual cues used in purchasing decisions. Researchers discovered that customers had stopped actively shopping by the time they reached the checkout. Because the customers were no longer shopping—just visiting—the products didn’t have a chance of stopping, holding, and selling.

The researchers realized they needed a trigger to reignite the shopping mode at the checkout. And, because “freshening” is the overwhelming motive for purchasing chewing gum, researchers recommended that refreshment cues be introduced in the approach to the checkout area. The company then employed a group of experts to establish the visual elements that signal refreshment. The group recommended imagery that strongly communicated refreshment and which shoppers could instantly decode and associate with chewing gum. Dandy next commissioned in-store marketing material based on these signals for use in the key pre-checkout area. There were four graphic directions, each of which could be adapted for individual retail customers to promote the entire chewing gum category.

The next stage of the project was to confirm that refreshment and breath-freshening cues in the pre-checkout area do increase sales in the chewing gum category, and by how much. Dandy undertook research in two stores in Denmark, Kvickly supermarket and OBS hypermarket. Overall, nearly 20,000 customers were filmed at four checkouts in each outlet. Two checkouts per outlet had the trial setup and two provided experimental control. Dandy found that the new point-of-purchase material did indeed stimulate consumers to revert to shopping mode and attracted more of them to that checkout area. The new strategy increased the sales of all the categories represented in the display by an amazing 40% and Dandy’s sales by up to 44%.

This is a major boost in sales just by retailers and manufacturers working together to understand shopper behavior. The retailer had to rethink its checkouts. The manufacturer had to rethink its in-store marketing. This is a different relationship than a passive retailer receiving stocking fees from a brand owner to gain shelf space. This is creating a more compelling sales opportunity for shoppers, reflecting an understanding of the three moments of truth for the shopper. If visitors are not converted to shoppers and shoppers are not converted into buyers, there is no sale. Working together, the retailer and manufacturer increased sales, which benefits both of them.

Beyond Category Management

As this example illustrates, collaboration between retailers and manufacturers can help both. This partnership between manufacturers and retailers moves beyond traditional category management to active cooperation in management of parts of the store, or even total store management.

To understand this evolution, we need to consider the evolution of the concept of category management over the last decade or so, as retailers and their brand partners began to realize they needed to take a more shopper-centric approach. Category management began in the early 1990s when Brian Harris of The Partnering Group set out a number of “best practices” for collaboration between suppliers and retailers. Basic category management, still in widespread use, involves retailers and suppliers using sales data to answer questions such as: How should the products on the shelf be segmented? What should the layout be? How can SKUs be optimized? How many items should be on the shelf? Which ones? More brands or fewer brands? What about different pack sizes?

The next level, category reinvention, has come to the forefront over the last few years. This is far more extensive, going beyond segmentation, assortment, and pricing decisions to include such elements as themes, fixtures, signage, size, layout, location, paths, adjacencies, flow, assortment, and planograms. This approach is becoming more prevalent because it is more engaging and encourages higher levels of conversion by offering a more emotional experience. A meat department, for example, might be creatively reinvented to look like a butcher shop. The coffee aisle might be redesigned to give a coffeehouse experience.

A New Era of Active Retailing: Total Store Management

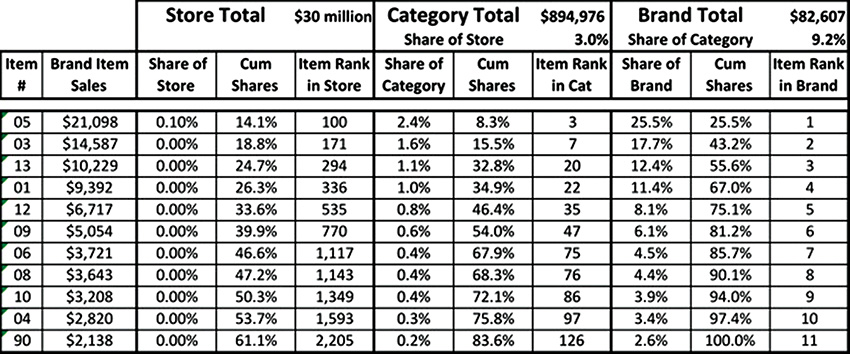

Category management, aisle management, and even store management are blunt instruments. They lump products and categories together. Item management, on the other hand, is a scalpel, targeting the small number of items in the store that are major levers for sales. The typical approach to category management is for every category to have its place in the store. But if the individual products were instead totally randomized through the store, the shopper would be more exposed to more categories. Taking this approach to this extreme might lead to chaos, but secondary placements in the store do move retail in this direction by putting items in unexpected places, and managing individual items that drive store sales. The Long Tail of the store may be organized by categories, but the Big Head should be placed where shoppers can find it.

A third and higher level of category and aisle management is emerging, which is a natural progression from category management and the drive to create a real partnership between active brand owners and active retailers. Total store management takes a much broader perspective, with manufacturers working with retailers to design their total store layouts. This goes to the specifics for all the major categories, both in organization and arrangement in the main store, as well as in the promotional store. This progression from category management to aisle management and on to total store management can be seen as part of the accelerating movement from passive to active retailing that is now underway.

There are several reasons why this approach is attractive, particularly to larger brand owners. First, they often have products all over the store. Coca-Cola, for example, has products in the water section, in juices, in teas, and so on. Anything the brand owner can do to maximize the performance of the total store is going to improve its business. Second, when companies have a very large category—confectionery, say—overseeing the store in a holistic way means they can exploit their positions not just in the primary display areas, but also in the secondary, promotional display areas such as endcaps and the checkout, where an average 30% of purchases are made. Instead of fighting for space in the center aisles where shoppers are reluctant to come, manufacturers can take their brands out to the shoppers more effectively by looking at the total store.

A sophisticated large European confectionery manufacturer, for example, worked with a major retail partner to determine the ideal layout for stores, addressing the following questions:

![]() Identifying leaders: What are the steering categories in the retailer’s stores, which genuinely move traffic? Remember, there are typically a small group of categories that do move traffic, the leaders—the rest are just along for the ride.

Identifying leaders: What are the steering categories in the retailer’s stores, which genuinely move traffic? Remember, there are typically a small group of categories that do move traffic, the leaders—the rest are just along for the ride.

![]() Arrangement: In which order should different categories within a given arrangement ideally be placed?

Arrangement: In which order should different categories within a given arrangement ideally be placed?

![]() Interaction: In what way is the usage of different categories influenced by the location of other categories?

Interaction: In what way is the usage of different categories influenced by the location of other categories?

![]() Order: What is the optimal order of planned categories, impulse categories, and the categories “in between” (if they exist)?

Order: What is the optimal order of planned categories, impulse categories, and the categories “in between” (if they exist)?

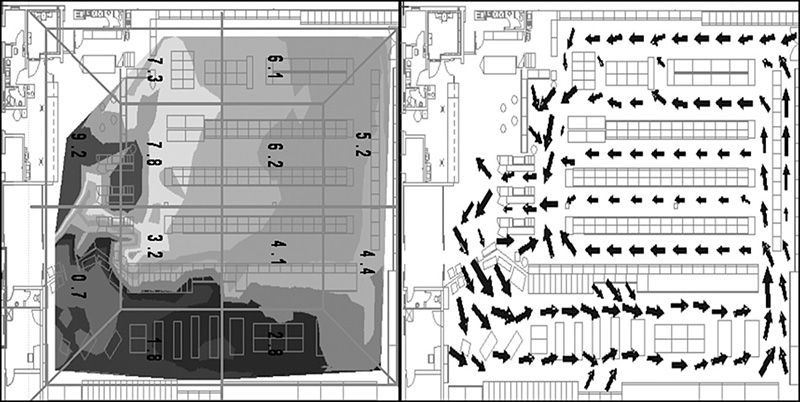

All these questions are essentially behavioral questions. That is, if we can understand exactly how all the shoppers behave in the present store, this will serve as the foundation guide to how it might be altered to enhance that behavior to the mutual benefit of shoppers, the retailer, and their brand suppliers. To study shopper behavior, researchers began by analyzing how shoppers move through the store. In this case, data was collected by “shadowing” shoppers, recreating their trip with various behavioral annotations on a web tablet, as illustrated in Figure 10.1. The paths of individual shoppers were charted, as shown in the right side of the figure, and then paths of many shoppers were amalgamated. The methodology used here, Personal PathTracker, is one of many methods for creating this data, including radio-frequency idenification (RFID) tracking, video tracking, or shopper vision tracking.

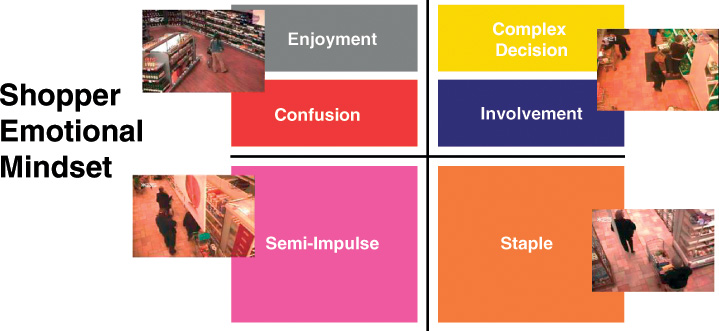

Figure 10.2 shows the trip progression of these many shoppers in a stylized form. The numbers indicate how far along in the average shopping trip the shopper is, beginning at the lower left (0.7 = 7% of the trip) to 1.8 and 2.8 to the right, and so on, through the store to the 9.2 at the end of the store. The numbers are across many shoppers so the reason it doesn’t go from 0 to 10 is that no matter how many people are heading one direction, there is always someone going the other direction. If nearly everyone ends their shopping trip at the checkout, there will be someone who begins there and moves in the opposite direction, both in terms of traffic flow, on the right, and time point (progression) in the trip. The arrows in the right side of Figure 10.2 represent the dominance of traffic, not the volume of shoppers. (A small arrow, for example, means that the number of people flowing both ways is about even. A larger arrow means that traffic is predominantly in that direction.) The researchers used the metrics summarized in Table 10.1 to understand shopping behavior in the store.

The complete flow and adjacency analysis produced six key insights, as follows:

![]() Understanding store and aisle traffic flow, hot spots and cold spots, and target shopper segments: Researchers gained insight into the dynamics of movement of individual shoppers, as well as the overall flow of the crowd. This allowed identification of points of congestion and fixture location issues that might restrict traffic flow to all parts of the store. The goal was to open up and encourage traffic in an orderly way, to maximize the opportunity to offer the shopper the right merchandise at the most receptive point in their shopping trip.

Understanding store and aisle traffic flow, hot spots and cold spots, and target shopper segments: Researchers gained insight into the dynamics of movement of individual shoppers, as well as the overall flow of the crowd. This allowed identification of points of congestion and fixture location issues that might restrict traffic flow to all parts of the store. The goal was to open up and encourage traffic in an orderly way, to maximize the opportunity to offer the shopper the right merchandise at the most receptive point in their shopping trip.

![]() Identifying “leader” categories—high performers for stopping and buying power: These “leaders” may be identified in the Vital Quadrant™ analysis discussed in Chapter 2, “Transitioning Retailers from Passive to Active Mode,” There we saw that there is not an iron-clad identity of these across all stores, but certain categories do appear again and again on the leader list. We also identified a series of categories through statistical clustering of shoppers by their trip behavior, which are common to the largest groups of shoppers, whether for quick, fill-in, or stock-up trips. Even though the metrics and analytical approach are not identical, there is significant overlap between the groups.

Identifying “leader” categories—high performers for stopping and buying power: These “leaders” may be identified in the Vital Quadrant™ analysis discussed in Chapter 2, “Transitioning Retailers from Passive to Active Mode,” There we saw that there is not an iron-clad identity of these across all stores, but certain categories do appear again and again on the leader list. We also identified a series of categories through statistical clustering of shoppers by their trip behavior, which are common to the largest groups of shoppers, whether for quick, fill-in, or stock-up trips. Even though the metrics and analytical approach are not identical, there is significant overlap between the groups.

Other independent groups, working with RFID trip data, using intelligent agent modeling, found a similar group of categories whose impact on the shopping trip accounted for the total store traffic, in terms of density and flow. This type of convergence from multiple analytical approaches gives us added confidence, not only in the role of the leader categories, but also that the great majority of categories in the store do not drive shopping behavior and that purchases occur largely incidentally to those driven by the leaders.

![]() Determining the ideal placement of “leader” categories to maximize performance and improve flow throughout the store: Categories with high stopping power (visitor to shopper conversion) are given priority early in the shopper’s trip (progression). This gets the shopper started off on the right foot, by beginning to fill the basket early. This also means that they’re willing to spend more time on these purchases, making more of them, because they will tend to shop faster and faster, or spend less and less time, the longer they are in the store. It is also helpful to consider category buy time, trip type, and level of planned or impulse purchasing of the category.

Determining the ideal placement of “leader” categories to maximize performance and improve flow throughout the store: Categories with high stopping power (visitor to shopper conversion) are given priority early in the shopper’s trip (progression). This gets the shopper started off on the right foot, by beginning to fill the basket early. This also means that they’re willing to spend more time on these purchases, making more of them, because they will tend to shop faster and faster, or spend less and less time, the longer they are in the store. It is also helpful to consider category buy time, trip type, and level of planned or impulse purchasing of the category.

![]() Identifying leader category “affinities”: Affinity means that when one product is purchased, then another is often purchased as well. This analysis helps determine the placement of these affinity categories to maximize their performance and improve flow throughout the store. Because we have data on trip progression, we can then place these affinity categories in the right order in the path of the shopper.

Identifying leader category “affinities”: Affinity means that when one product is purchased, then another is often purchased as well. This analysis helps determine the placement of these affinity categories to maximize their performance and improve flow throughout the store. Because we have data on trip progression, we can then place these affinity categories in the right order in the path of the shopper.

![]() Placing remaining categories using similar analysis procedures: Once the leaders are positioned, the remaining categories can be placed based on margins and relevance to the other categories, as well as the guidelines offered for niche, high interest, average, and underdeveloped categories.

Placing remaining categories using similar analysis procedures: Once the leaders are positioned, the remaining categories can be placed based on margins and relevance to the other categories, as well as the guidelines offered for niche, high interest, average, and underdeveloped categories.

![]() Identifying ideal placement, contents, and messaging for promotional (secondary) displays: This is done through visual audits of stores—what’s seen and what’s not seen—as well as a detailed accounting of the exposure to shoppers of various endcaps in stores.

Identifying ideal placement, contents, and messaging for promotional (secondary) displays: This is done through visual audits of stores—what’s seen and what’s not seen—as well as a detailed accounting of the exposure to shoppers of various endcaps in stores.

The results for this specific store were impressive, with post-redesign surveys showing that shoppers were very satisfied with the results and were likely to recommend the store to others. Specific sales lift improvements cannot be disclosed, due to proprietary concerns, but management consistently reports sales increases from a few percentage points to double digits after active retailing redesigns.

Pitching a Category’s Emotional Tone More Precisely

One of the biggest questions retailers and brand owners have to answer is how to promote individual categories in the store. What should the emotional tone of each one be? Siemon Scammell-Katz introduced a set of powerful tools for merchandise promotional planning to address the type of promotions appropriate for various categories.

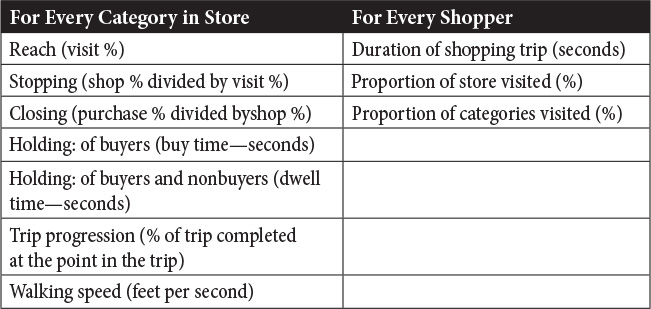

The foundation of the methodology was the evaluation of in-store shopping metrics from a large number of shoppers in a single U.K. supermarket linked to data from the same shoppers, as tracked over years in the TNS World Panel. Researchers found that two of the most significant variables in conversion rates are buy time (how long the purchase takes in minutes) and purchase frequency (on an annual basis). This analysis helped identify the emotional involvement of different categories. The categories are divided up based on these metrics and then restated in terms of the emotional mindset that shoppers are likely experiencing, given their investment of time in the purchase and its frequency, as illustrated in Figure 10.3.

Those emotional mindsets then provide guidance for appropriate communication strategies, to reach shoppers with the right type of messages, for the right emotional states associated with specified categories. For example, the categories that are high frequency but low involvement are most likely to be staples (in the lower-right quadrant). This in turn leads to a rational communication strategy appropriate to the category. For staples, for example, it should be about range reduction and ease of shopping. For “enjoyment” categories, it should be “theater,” and for “involvement” products, the focus should be on providing information. Although this is a practical scheme for managing communication strategy in the store, it does not, of course, dictate the creative strategy. As noted earlier, a hot pink package might capture attention but may not make the sale, so there is plenty of room for creativity in communication.

The examples we have used for illustration are largely drawn from supermarkets and consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) or fast-moving-consumer-goods (FMCG) retailing. Our largest experience has been in this arena. But the most valuable asset here is not the massive normative database providing insight to CPG/FMCG, but rather the organized, scientific approach to retailing. We have applied this schema across a broad spectrum of retail trade around the world, including sectors such as autoparts, home electronics, phone stores, gift/card stores, clothing, jewelry, and so on. Moving from country to country, and across classes of trade changes the values of the metrics, but it does not change the organizational paradigm. Wherever we have gone in the world, we have found that most people are right-handed (hence the inherent trend to navigate a store in the counterclockwise direction). In similar fashion, across wide swathes of human behavior, there is more that makes us alike than different.

Retailers Control Reach

One challenge in the traditional relationship between retailer and brand owner is that the retailer controls the first stage of the sale: reach. Retailers control the design and layout of the store, so brands usually need to work within this framework. The passive retailer views reach as visiting: It’s the shopper’s responsibility to visit a product if they want it. Passive retailers also want to keep shoppers in the store as long as possible, so if products are difficult to find, or inconveniently placed, they reckon they are doing their job well. This attitude, which is locked into so many retailers’ minds, is unhelpful. Supermarkets, for example, usually put the milk at the far corner of the store because they believe it will make people go there. Well, they very possibly won’t. Instead, they may stop at the convenience store or a competitor if it’s easier.

This creates great problems for brands because brand suppliers have to work through retailers to accomplish anything in terms of reach. First, people tend to shop with the subconscious expectation that they are going to buy just so much “stuff.” When they have the right amount, they are going to leave the store as quickly as they can. They are not going to anguish over whether they have Brand A or Brand B. In fact, even if they usually buy a particular brand, and the retailer moves it elsewhere, the shopper might not realize it and no longer use that brand for some time, if at all. This is the real challenge for the brand owner: The retailer is relatively indifferent about what people buy as long as it is a reasonable amount and they do so with some frequency and efficiency. Brand owners try to address this careless attitude through promotional fees, but it is a crude instrument. Brands make the real difference in stopping power—after the shopper comes into the product’s orbit. But the shopper first has to get close enough to see the brand. To address this challenge of reach, brand owners need to work with retailers to more effectively position the brand in the store.

After the shopper comes into reach of the product, its “visual equity” from branding and packaging makes a huge difference, particularly among the crowded Long Tail products. Packaging is the number-one communication vehicle at retail. It is the most viable method the brand has for communicating with shoppers. The shape and color of the package—visual equity—that consumers associate with the brand (such as Coca-Cola’s color red) allow the consumer to quickly identify products among the clutter at the point of purchase, in the pantry, or on the tabletop.

The Urgent Need for Retailing Evolution

Retailers are harvesting massive cash from the brand manufacturers for representation in the promotional area. Meanwhile, brand manufacturers are spending further billions on researching how to manage the main store. The two parties are both distant from actual shopper behavior—to the financial detriment of both. These economics are the foundation of the supermarket’s profits but are killing the brands, whereas the shoppers tolerate this modus operandi because so far there are few other options.

We reemphasize here that we are not advocating retail revolution but are excited about the continuing evolution and hope to contribute to it and perhaps accelerate it. What we want to eliminate is the thinking that says: “Shoppers are in the store, and it is just too difficult to conduct research there. And it is also much too difficult to master the promotional store. So we, as the brands, will continue to invest in aisle/shelf management. And we, as the retailers, will continue to develop our promotional store for ourselves.” They should both be focusing more attention on the promotional store—the Big Head. That is where the money and the opportunities are.

We also suggest that the strategy of putting promotional pricing on the items on the endcaps is seriously misguided. Instead of trying to train shoppers to think: “If I want to get a deal, I should just grab something right here,” they should think: “If I want a deal, I know I’m going to go down that aisle to get it.” Retailers and brand owners should understand that their pricing and promotional strategy is highly irrational.

Brand suppliers, meanwhile, need to know how to maximize and optimize their secondary display performances: where the displays should be, what kinds of products should be on them, the type of message to attract the shopper and convert them to buy, and so on. It is not that brands do not work in this second store but that, because it is far more complicated and difficult, the focus tends to be on the section of flat wall in the main store over which they have some influence or control, and which is much easier to study and understand.

Promotional spending of big brands distorts the shopping experience in ways that are not good for the shopper, the retailer, and, often, even the brand owner. If I were a retailer, I would fiercely manage the Big Head strictly for the benefit of the shopper, and insist that the promotional “crack cocaine” not override the behaviorally expressed wishes of my shoppers. If you don’t know how to manage the Big Head part of the store strictly in the shoppers’ interest, learn or retire. I would continue to allow the Long Tail to be a battleground for the brands—and profitable for them, too. But the rational ones of them will want to know what they are getting from their share of that trillion dollars of retail spending. No problem. It is urgent that you know the value of every inch of real estate, every aisle location, every end-aisle display, every shipper, every lobby display, and all the in-store media. I’m talking about approximately monetizing every inch of the store.

Review Questions

1. Discuss how the development of the retail industry caused retailers to ignore shoppers and shopper behavior focusing on other KPIs? Why should this change now?

2. Describe how the evolution of retailer own or private label brands could change the power balance between national brand manufacturers and retailers.

3. Thinking of category management—what actions could retailers and brand manufacturers consider together to improve shopper experience in the category and profit outcomes for all stakeholders?

4. Reflect on the key differences between a traditional tool of category management and a more progressive approach of aisle and whole store management. How do relationships between retailers and manufacturers need to change to make this new approach work?

5. Discuss the concept of “leader” categories. What is the role of the “leader” categories in shopper stopping and buying power and the whole store-management approach?

6. Describe the main sources of supermarket profits in decreasing order of importance and contribution.

7. What does the author mean by “reach” as a shopper metric? What is the difference between how passive and active retailers influence reach? What challenges passive approach to reach present to brand manufacturers? Discuss why putting milk at the very back of a store could be a problem.

8. Discuss the elements of retail evolution. Which parts and practices of a passive store could be improved and how?

Endnotes

2. Neff, Jack, “Brand Giants Weakened as Retailers Get Savvier,” Advertising Age, October 6, 2008.