19 The specialists

No lesson seems to be so deeply inculcated by the experience of life as that you never should trust experts. If you believe in doctors, nothing is wholesome; if you believe the theologians, nothing is innocent; if you believe the soldiers, nothing is safe. They all require to have their strong wine diluted by a very large admixture of insipid common sense. Letter to Lord Lytton, 15 June 1877; in Lady Gwendolen Cecil, Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury)

The above caveat may be well over the top but specialist feature writers need to keep in mind that the expert professionals they consult usually have an agenda whether conceded or not. The general principle of checking and counter-checking holds good. We need experts much more these days, of course, as we try to keep up. Experts who turn to journalism, generally as a part-time occupation, are highly valued by editors, especially if they don’t need too much editing, if they can acquire the journalistic skills, get on the audience’s wavelength, bring in the common sense, avoid a narrow viewpoint and jargon.

This chapter addresses both experts-turned-journalists and journalists-turned-experts (of a kind). We’ll call them all specialists, for convenience. Specialists are in demand to fill the regular slots, from the arts to zoology, in the newspapers, in the consumer magazines, in the specialist magazines. Some of the specialist writers start by accident. On a local paper versatile staff writers may cover for the health experts when the established ones are on holiday. The former may become hooked on the subject. The trick then may be to identify gaps elsewhere and make pitches.

Even so, it’s wise to remain versatile to some degree: the specialisms (and the publications devoted to them) come and go. There was a moment when there was huge demand for writers about computers; a later moment saw many of the magazines going to the wall.

We have already met specialists in Chapters 17 and 18. The subject matter of the specialist columnists and reviewers, however, is a mix of fact and opinion, of the subject outside and the subject within themselves. (To generalize dangerously.) This chapter moves on to the more professional or more scientific/technical subject matter.

Wherever they’ve come from, with whatever motives, specialist journalists must have a passion to communicate, a desire to share their curiosity, interest and excitement about the subject with an audience. That often means, as well as the usual informing and entertaining, getting feedback from readers, developing a dialogue with them. Specialist, like general, columnists encourage this by supplying their email addresses, and sometimes some of their sources so that readers can take the subject further.

The techniques described in this chapter have already been covered in this book. The purpose now is to show how to adapt those techniques to specialist writing: to detecting opportunities, devising a marketing strategy, to pitching, deciding on content, structure and style, and to researching. There follow commentaries on some samples of published specialist features.

OPPORTUNITIES GALORE

The pace of change accelerates constantly. People find it hard to manage the flood of information reaching their own patch of expertise. They need experts in their field or in associated fields to guide them in selecting relevant information and applying it.

Specialist writers for the prints thus have the advantage that they are badly needed. Being on top of their subjects gives them the further advantage that they know where to get their information from and they know how new information is being applied. Unless their journalism is strongly research-based, the time needed for research may not be great.

Opportunities, apart from the journalistic ones we’re mainly concerned with, are much varied: reports, booklets, manuals, brochures, publicity materials, etc. for government departments, associations, business organizations, PR companies; and books and scripts.

At one time the slowness of top professionals to recognize the need to communicate to wider audiences was compounded by the slowness of editors to seek out their services. Academics, especially Oxbridge ones, were discouraged from publishing outside the journals for their disciplines. A. J. P. Taylor was passed over for professorships in Modern History at Oxford in the 1950s because of his (brilliant) features in the Sunday Express and TV talks. This has changed. Larger papers with supplements and a spectacular increase in magazines, including specialist magazines, has attracted many specialist writers, and popularizing is no longer such a dirty word.

Finding up-to-date ideas

Specialist writers keep up to date with what’s going on in their field. If you’re not teaching it or earning most of your income by being employed in it you need to make special efforts to ensure that you’re reading the right literature, having access to the right reference books and talking to the right colleagues.

The right literature includes the newspapers and magazines, and scripts of radio and TV documentaries if available. The indexes to articles (BHI, The Times Index, Willing’s Press Guide, the specialist magazines’ indexes, etc.) will guide you to recently published pieces. You will note on which days the quality papers deal with, or have a supplement covering, your field. For example, taking a random selection at the time of writing, The Times has a daily supplement (T2) covering most days the arts and health, the media and education on Tuesdays; and there’s a business supplement on Wednesdays. The Guardian also has a daily supplement (G2) with similar coverage to T2 and special supplements on the media (Mondays), Jobs and Money (Tuesdays), and Society (Wednesdays). The weekend (Saturday) and Sunday packages of the qualities are bulky, with various kinds of supplements. The Week alerts you, as we’ve seen, to one or two of ‘the best’ of the week’s features on the arts, and it provides the same service for other specialisms.

There are many ways a writer can exploit reference books for article ideas, some of which have been mentioned in earlier chapters. Some ways are not obvious. PR consultancies dealing with specialist areas (see The Hollis Press and Public Relations Annual) will provide you with masses of information on your subject. So will the publicity departments of business organizations.

The research sources listed below and in the Bibliography are an obvious source of ideas.

A MARKETING STRATEGY

The research results or latest developments reported in specialist journals can form the core of features for newspapers and magazines. A rule-of-thumb principle for finding information or a story in one kind of publication and adapting for another is to go more than one level up market or down. For example, medical specialists can more easily use the research material of The Lancet for an article in Woman’s Own or their local paper than for such professional magazines as GP, Pulse, Doctor or Modern Medicine. For the middle-range professional magazines may be too well aware of the contents of the more specialized journals.

Conversely, the same medical specialists will find interestingly angled stories in the popular markets that they will know how to develop by a little research. A story about an elderly person surviving laser surgery will send them through the specialized geriatric journals for detailed coverage of the subject. They may obtain material to rework in several ways – for a technical publication, one of the health magazines, or for magazines for the elderly like Saga, or for those who care for them.

Before attempting specialist features, make two lists, side by side:

1 The sort of features you think you could write.

2 The gaps you perceive in the market.

Pitching to specialist publications

Specialist publications have a clearly defined editorial policy for a clearly defined audience and that’s why they need close scrutiny. Ideas for specialist features are often developed in-house and may require careful briefing and ongoing feedback (see Figure 19.1). But the specialist pages of newspapers and general interest magazines should also be market-studied with extra care. Here are some dos and don’ts:

• Show that you have market-studied the target publication.

• Angle your proposal so that it’s right for the readership.

• Indicate your background and qualifications briefly. A summary of career might help, and samples of published specialist features (see Campaign’s, briefing policy in Figure 19.1).

• Don’t propose ideas covered recently.

Figure 19.1

Briefings from Campaign’s features editor. With kind permission of Campaign

• Don’t invade the territory of well-established contributors, unless you’ve identified a neglected aspect.

PRODUCING SPECIALIST FEATURES

What are the special considerations, in terms of content, structure and style?

Approach to content

Your approach to content has to take account of the vast differences in the needs of specialist markets. Business-to-business publications (previously called trade and technical) will on the whole be happy with features that can assume readers’ interest for the subject’s sake. For more general and more popular publications the thrust of a piece will need to impinge more practically on the lives of its readers.

In spite of these differences the following approach to content should underlie any piece of specialist journalism:

1 Pitch the information at the right level. For example, suppose you are describing a solar plant in operation. At the popular level the aim will be to make the reader appreciate how the plant works, probably with the help of simple analogies, anecdotes and perhaps simple diagrams or other illustrations. If addressing solar plant engineers there will be complex scientific/technical explanations. There are many levels in between. The level of discussion will determine which facts you select, which technical terms you use, which you will explain, which processes you describe.

2 Remove misconceptions and clear the ground for the necessary definitions and for fruitful explanation, argument, discussion. An article by Sir Fred Hoyle and Professor Chandra Wickramsingh listed some of the mythical origins of the Aids disease – Haitian pigs, African green monkeys, God, Russians in chemical warfare labs. A psychiatrist noted how readily people (and the media) believed the murderer of members of his adoptive family when he accused his mentally ill sister (also dead) of the crime. ‘The mentally ill are mistakenly assumed to be particularly prone to kill others and then themselves.’

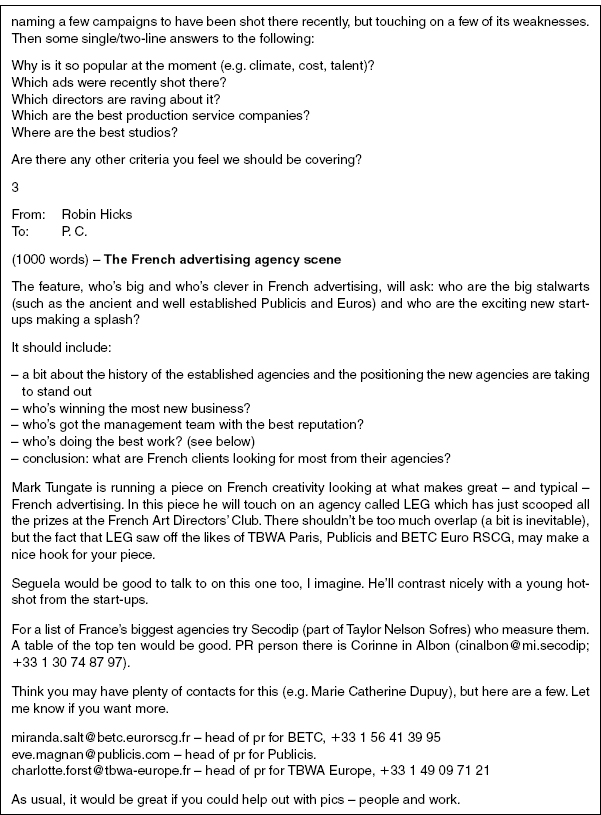

3 Illustrate in various ways. A verbal explanation may not be enough. Figure 19.2 shows a page from an article about basket-weave bricklaying, by a lecturer in the subject, with illustration backing up the text.

Verbal illustration by such means as simple example, analogy, anecdote or quote is essential in much specialist writing. There are 100 calories in three cubes of sugar. The light from the Pleiades started its journey when Shakespeare was seven years old. Sleep to the brain is ‘offline processing’. The lens aperture of a camera is like the pupil of an eye, dilating or contracting in proportion to the light, and so on.

Figure 19.2

Line drawing with technical detail: from Building Today, 24 March 1988, page 23. Reproduced with kind permission

4 Interpret information by relating it to people. Identify likely benefits and warn about the possible dangers of discoveries, developments and processes. The education specialist, for instance, considers how current education policies will affect employment patterns. Writers on biogenetics warn that politicians may be tempted to exploit developments in cloning.

Shaping up

Specialist features are read by people avid for information, explanation, instruction. Information must be organized so that it’s easy to take in, refer to and remember. The approach is essentially to:

1 Select points and structure them carefully, using headings if necessary. Don’t make the texture too dense. In how-to features of fair complexity readers will put up with some repetition (but not with digression) because it gives them breathers as they busily ingest all the information, as long as there’s a steady progression.

Notice how the repetition of ‘brick’ and ‘softening’ and the examples in this paragraph from that Building Today bricklaying article spaces out the information so that it is easy to take in:

When a number of raked cuts have to be completed, as in diagonal basket weave or gable construction, use a softening material under the brick to take the impact out of the blow that a hammer and bolster would create. This decreases the possibility of the brick fracturing. Some good methods of softening are a bucketful of dry sand or a small square of old carpet.

2 Anticipate readers’ questions. List them, then put them in an order that will create a logical progression and you’ve probably got a good outline to follow.

3 Suggest solutions to problems, or raise the most important questions, and make intelligent predictions about the future. This is often a good way to end a feature.

Outlines in logical order

A 1000-word piece at a specialist level on the current attempts to rehabilitate ex-prisoners in the community aimed at New Society or the Society supplement of The Guardian might be planned as follows:

Intro

• Hook: setting the scene with a case study or two

• Bridge: background, definitions, removal of misconceptions

• Text: thesis – the rehabilitation must start in prison and there must be adequate follow-up.

Body

• Policies that have failed and why

• The various social problems in the chain

• Likely approaches/solutions, with case studies.

Conclusion

• Summing up/justification of the thesis.

This could be expanded into a detailed outline with sources indicated. It’s advisable to work from a more detailed outline for longer features. Let’s stay with social problems. A 2500- to 3000-word or longer feature on the treatment of alcoholics would have an intro and a conclusion along the same lines. The outline of the body could have the sources slotted in. You might work in this way:

Your notes can be divided into sections with headings: 1, 2, 3, 4, …. Your source materials can be labelled A, B, C, D, … and put to the side. They would include, say:

| A | The NHS |

| B | Alcoholics Anonymous |

| C | Institute of Psychiatry |

| D | Rutgers University, New York |

| E | Drink Watchers organization |

| F | Edinburgh research unit |

| G | National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

| H | Directory of Psychology and Psychiatry Encyclopaedia. |

The notes might come from books, journalism (consult the indexes), literature of the above organizations and from legwork/interviews involved in visits. The notes might provide the following headings, with the sources indicated:

1 Definitions of alcoholism (C, H)

2 The main causes (C, G, H)

3 Recent developments, e.g. among women (journalism, G)

4 Two kinds of cure – controlled drinking and abstinence (B, F)

5 Most successful treatments (D, F)

6 Least successful treatments (D, F)

7 Lack of funding for research/medical facilities/voluntary organizations (A, G)

8 What needs to be done (journalism, D, G).

One way of working with this outline is to allocate half a page to each heading and slot underneath it the most significant or most striking acts, quotes, anecdotes, whatever, from the notes and literature. In the margins of the pages you can indicate any links that occur to you.

You may want then, if you feel saturated with the stuff, to write a first draft from memory, using the second draft to fill in the gaps by referring to your materials, and to polish.

Some commissioning editors, especially in the USA, like to see your pitch in the form of an outline with research sources indicated, as above, plus a proposed intro. A paragraph summarizing what will come after that might also be welcome. This is especially likely when your feature is to be long, fairly complex and based on a fair amount of research. See for example the booklet Writing for Reader’s Digest, obtainable from the publishers. A reminder: you don’t have to give up your confidential sources.

From the above example it’s clear that you could develop a proposal for a book from a detailed feature outline, by expanding research sources and commentary.

Finding the right language

The care to get the approach to content and structure right will be undermined by ineffective language. Check for the three Cs – clarity, conciseness and coherence – in the words, sentences and paragraphs as well as in the overall effect:

• Is every word necessary, immediately comprehensible? Will any of the jargon need to be explained? Would a glossary be useful?

• Is every sentence relevant, comprehensible at first reading?

• Are the sentences and paragraphs in the best order for effective description, explanation, instruction?

The use of jargon

The CED defines jargon as ‘words or expressions used by a particular profession or group that are difficult for others to understand’. Explain a term if you think a fair number of readers will find it unfamiliar, but do so unobtrusively so as not to bore others. Readers of Building Today were assumed to be familiar with ‘soldier course’, ‘dimension deviation’ and ‘rebated’. Much jargon, even if unfamiliar, will be understood from the context.

Other definitions of jargon are ‘debased language’ and ‘gibberish’. This is the unacceptable jargon that is developed by some trades and professions as a kind of slang with which only the initiated feel at ease, and which can keep others at a distance. Thus we have the National Health’s ‘bed throughput’. ‘the efficiency trap’, ‘the reverse efficiency trap’ and ‘increased patient activity’ (which has nothing to do with pillow-fights).

Sociologists are accused of ‘obscurely systemizing the obvious’. Some of this is done for the sake of political correctness. Is it necessary to call homosexuals ‘affectional preference minorities’ or stupidity ‘conceptual difficulties’? The International Monetary Fund has concocted some euphemistic ‘-ities’ ‘conditionality’, additionality’, ‘mutuality’. Computer nerds like ‘functionality’.

Watching that phraseology

Professionals or technicians who launch into addressing large audiences may bring some cumbersome phraseology with them. Here are a couple of samples:

If that statement appears obvious to the meanest intelligence, it must be realized that …

This has doubtless been said many times in the past, and doubtless will be said many times in the future, but …

A paragraph from an article about sales techniques runs:

Our research project starts from the assumption that communication is central to social life; perhaps nowhere is this more important than in selling.

In this context interpersonal skills appear to be integral features not only of sales success but also of commercial success in general.

This means that business success depends on establishing good relations with people. An article on management in the hotel and catering industries gets tenses in a twist:

Management … tends to be very young. It would be surprising to find so many executives in their twenties if the prospect of going into the industries hadn’t been so unfashionable in years gone by.

The image of continental waiters working long hours was a more normal perspective for parents than college graduates, well trained for a worthwhile career. In fact, there are more catering colleges in Britain than in any other EEC country.

This is more clearly and concisely expressed: Management … is young because it has been an unfashionable career. The image has been overworked waiters rather than college graduates …

The context needs to be firmly in the present; in other words past situations require the present perfect. The clutter of abstract nouns such as ‘prospect’, ‘image’, ‘perspective’ – in any case an image is not a perspective – doesn’t help.

The classics on good English usage that steer us away from gobbledygook (Gowers, Orwell and others – see Bibliography) are well worth the space on our shelves.

On the same wavelength

If you’re going to aim at different kinds of publications, study the writers who do it. Dr James Le Fanu turns up all over the place. Here he is in The Financial Times, reviewing a book by D. M. Potts and W. T. M. Potts, Queen Victoria’s Gene:

Argument centres on how Queen Victoria acquired the haemophiliac gene which she passed down to her various offspring. It could have been a spontaneous mutation, a random garbling of the microscopic part of the DNA that coded for the production of Factor VIII, which is essential for the clotting of the blood.

Moving to GQ magazine (in a column called ‘What’s up, Doc?’) he gives us:

In the 22 years from 1969 to 1991, concentration of all the major air pollutants – sulphur dioxide, ozone, particulates and oxides of nitrogen – declined by 50 per cent in the city of Philadelphia, while during the same period mortality rates from asthma increased markedly. Even more intriguing is a study of the prevalence of asthma in Britain, which shows that it is more common on the non-polluted island of Skye in the western Highlands of Scotland than in urban Cardiff.

He, like many other doctors and health professionals, find many opportunities up and down market. Dr Vernon Coleman, author of many self-help books, knows how to get down-to-earth for The People. Here he advises a caravan couple suffering from the bad behaviour of children in the next caravan whose parents regret that they are hyperactive and cannot be controlled:

Bollocks. The chances are that if you could stick the little bastards up to their necks in a vat full of warm sewage for 10 hours they’d soon learn some manners. Most of the children diagnosed as suffering from ‘hyperactivity’ are no more hyperactive than they are rabid.

The best way to annoy people in caravans, says the doctor, is to throw bread on to the roof. The seagulls dancing on the metal roof ‘will quickly drive your neighbour potty’ and they will then go home.

Me, I make no comment.

SAMPLES PUBLISHED

At the time of writing here are a few recent samples of the numerous specialist subjects covered in features:

Business

The Observer Food Magazine (Andrew Purvis): ‘Loaded’ – why supermarkets are getting richer and richer.

Financial Times (Roger Bray): ‘Flight path to the new Europe’ – airlines expect many new routes after eastward expansion of the EU.

Computers

The Sunday Times (Barry Collins): ‘Make commuting work for you’ – make the most of your laptop on the train by surfing, playing games, and so on.

Internet Magazine (Heather Walmsley): ‘Sweet Charity’ – interview with Anuradha Vittachi, Director, OneWorld International Foundation, which gives voice to small charities around the world.

Education

The Independent (Steve McCormack): ‘I used to bunk off … No longer’ – teenager truants take to an employment skills programme in Kingston-upon-Thames.

The Independent (Caroline Haydon): ‘Should tots be tuning in?’ – preschool children lack the language skills of previous generations.

The Daily Telegraph (Madsen Pirie, president of the Adam Smith Institute): ‘Helping the public to go private’ – a Ryanair kind of revolution is recommended to bring private education to a wider public.

New Internationalist magazine (Hugh Warwick, writer and researcher on environmental and social justice issues): ‘Smoke’ – fuels burned on traditional three-stone stoves are killing at least 1.6 million people yearly.

Food

The Observer Magazine (Dr John Briffa): ‘When fatter is fitter’ – cutting cholesterol out of your diet can do you harm.

Health

The Daily Telegraph (Barbara Lantin): ‘Do you bend like Beckham?’ – one leg shorter than the other (which Beckham has) can cause back problems. (Telephone numbers of Health and Fitness Solutions and Institute of Chiropodists and Podiatrists.)

The Observer Magazine (‘Getting on top of your troubles is as easy as counting to 81,’ says Barefoot Doctor): ‘Winning numbers’ – exercises that prevent the mind racing and depriving the kidneys of energy, which causes anxiety. (Write or email him, or view his website.)

Daily Express (Dr Adam Carey, ITV Celebrity Fit Club expert and nutritional adviser to England’s World Cup Rugby team): vending machines in schools, full of junk food, refined sugar, salt and fat, are causing obesity, which leads to an increase in diabetes and asthma.

Time Magazine (Kate Noble, London): ‘Bad drug makes good’ – thalidomide, when used in the 1960s to treat morning sickness in pregnant women, caused terrible deformities in their children, but it is now showing possibilities as a cancer treatment.

Media

Press Gazette (‘Media misreporting of mental illness is no joke, says Liz Nightingale’ as strapline): ‘Time for a rethink’ – Ms Nightingale is media officer for Rethink, a campaigning membership charity involving people with severe mental illness and carers, with a network of mutual support groups around the country.

For up-to-date commentary on the media see the quality papers on the days when media columns appear, and subscribe to Press Gazette. For greater depth, also subscribe to British Journalism Review.

Medical science

Marie Claire (Jennifer Wolff): ‘Want to freeze your eggs until you meet Mr Right?’ – the ethical issues involved, with an account of a business selling models’ eggs for between £28,000 and £85,000, case studies of surrogate mothers and interviews with doctors and pressure groups.

Alternative/complementary medicine

She magazine (Linda Bird): ‘What’s the alternative?’ – brief accounts of the most popular forms: acupuncture, homeopathy, nutritional medicine, hypnotherapy, osteopathy and chiropractic.

Psychology Today (Michael Castleman, author of 12 consumer health books): ‘The Strange Case of Homeopathy. Miracle cure, placebo or nothing at all?’ – its mechanism of action cannot be explained scientifically but Americans believe that the combination of mainstream and alternative medicine will produce the best results.

Psychology

Psychology Today (Marina Krakovsky): ‘Caveat Sender. The Pitfalls of E-Mail’ – the lack of signals of rapport (tone of voice, nuances, facial expressions, and so on) can mean that emails can sound rude or indifferent, so if in doubt phone first.

Science/technology

Time Magazine (George Johnson, author of A Shortcut through Time: the Path to the Quantum Computer): ‘The Purr of the Qubit’ – an experiment taking scientists closer to the powers of quantum computing.

The magazine gives good coverage of this area, exploring subjects in depth through series of articles on separate aspects: for example, on the DNA revolution.

The Guardian (Life supplement, Ian Sample): ‘Science runs into trouble with bubbles’ – a US physicist claimed that an experiment triggered nuclear fusion by blasting a beaker of acetone, the key ingredient in nail varnish remover, with soundwaves: sonofusion.

Society

The Guardian (Society supplement, Tristam Hunt, historian): ‘Past masters’ – we can learn how to revitalize our urban centres from nineteenth century municipal visionaries such as Joseph Chamberlain.

Transport

Daily Mail (Op Ed, Christian Wolmar, writer and broadcaster on transport): ‘Le white elephant’ – the fiasco of the Channel Tunnel.

SPECIALIST COLUMNS

The specialist byline column can cover a wide range of subjects in a wide range of publications. To ensure continuity, you have to be bang up to date (especially with any new technology), ready with new angles, able to adapt your style to different audiences. The Oldie magazine has had two fruitful column formulae based on celebrities: ‘I once met …’ and ‘Still with us …’. Collect such formulae and work out ways of adapting them to your specialism without making it obvious that you’ve pinched them from The Oldie. Devise new formulae, take off from the feedback you get.

Decide on the essential aim of any new specialist column you’re about to pitch. Is it mainly to give advice or to entertain or to provoke to action, or all three? Is it to be an essay form, a three- or four-item menu, a catalogue of information (as in a consumer’s guide to cameras or computers), an interview feature, a Q-and-A interview, a Q-and-A using readers’ queries as in an agony column, a how-to column with headings?

You may want to experiment to see what works with your subject before pitching, so that your column will not look like any other within your subject area. Whatever the formula, your sample material must convince a potential editor that you can keep a column going indefinitely.

RESEARCH AND FACT CHECKING

The British Library’s Research in British Universities, in several volumes, gives details of research projects being undertaken in the UK, together with the names of experts in specialist subjects. The various Abstracts (Horticultural, Psychological, etc.) summarize the most significant of recent academic texts. You should also have access to the directories listing members of your profession or trade, with details of their work, such as The Medical Directory.

Use constant legwork, bringing people into your picture, to make sure you’re not rehashing old themes from research materials.

Specialist features need scrupulous research and fact checking. However much of a professional you are, you will depend at different times on interviews/quotes from experts in different disciplines that impinge on your subject, from the people in the middle (the care workers, for example) and from the people at the receiving end (the patients, for example). You’re always looking for different angles, to approach the truth. It’s advisable to get significant interviewees to check your script (to ensure the facts are right, the quotes accurate).

The much-in-demand medical/health features can be a minefield. Readers will depend on the information and advice given, especially if you’re a regular columnist. You need to be able to assess reliably the value to readers of information gathered online, from printed sources, new products publicity, interviews, and so on. Direct quotation may constitute a violation of medical ethics. Indirect speech and cautious summarizing are sometimes advisable: ‘cure’, ‘breakthrough’ and suchlike words should be avoided.

Specialists new to journalism may not be sufficiently aware how much information from apparently reliable sources can be inaccurate. It’s worth repeating that errors are repeated in newspapers for years. Press releases and other materials from organizations may contain errors of fact and wrong spellings of names. Faulty grammar may make for misleading content.

Professional organizations are listed on pages 389–90 and online sources on page 391–4.

ASSIGNMENTS

Choose two out of the following:

1 The Marie Claire article on fertility techniques mentioned above discusses some of the risks and ethical issues. After mentioning that ‘some [infertile] couples will pay any price to reverse nature’s fate’ two procedures were merely mentioned:

So, how far will we go to have a baby that’s genetically our own? The answer: as far as science permits. These days, women are travelling to Lebanon to have their ‘weak’ eggs supplemented with cytoplasm (the sticky liquid that surrounds the nucleus) from donor eggs, creating babies with three sets of DNA. Other couples are journeying to makeshift medical clinics in Mexico and Colombia, where the blood of husband and wife is mixed and then transfused back into the woman to create (hopefully) an immunity to miscarriage. This procedure has never been proved to be effective and is not available in Britain or the US, where it has been banned.

Write a feature of 1000 words for a popular woman’s magazine about these (if still offered) and other procedures, indicating experts’ advice.

2 Write a humorous but well-researched column of 800 words on the subject of greed for a target publication. Here to start you off are two paragraphs from an essay in New Internationalist of July 2004 by John F. Schumaker:

When we salute all-consuming America as the standout ‘growth engine’ of the world, we are in many ways paying tribute to the economic wonders of greed. William Dodson’s essay ‘A Culture of Greed’ chronicles America’s pre-eminence of a greed economy. He writes that the US enjoys a relative absence of constraints, including tax and labour constraints that would otherwise burden corporations with a sense of social responsibility, plus various system advantages and historical traditions, that together allow greed to flourish and be milked for purposes of profit and growth.

Jay Phelan, an economist, biologist, and co-author of Mean Genes, feels that greed could be our ultimate undoing as a species. Yet he theorizes that evolution programmed us to be greedy since greed locks us into discontent, which in turn keeps us motivated and itchy for change. In the past at least, this favoured survival. Conversely, he believes, it would be disastrous if humans lacked greed to the extent that they could achieve a genuine state of happiness or contentment. In Phelan’s view, this is because happy people tend not to do much, or crave much – poison for a modern economy. (New Internationalist, www.newint.org)

3 Rewrite the following extracts, for The Sun, The Mirror, the Daily Express or the Daily Mail, reducing each by a half and updating as necessary (indicate the target):

‘It’s the extended Internet. It’s the next generation of the Internet, which will mean the extension of Internet communications to all electronic devices,’ says Stan Schatt, vice-president of Forester Research in the US. The idea of devices talking to one another over the Internet has been with us for some time. Fridges that detect when your food stock is low and send an order to the supermarket over the Internet were confidently predicted during the Internet boom.

Such Internet fridges, or at least approximations of them, have indeed become available. Not many people have them. It turns out to be more difficult to get machines talking to one another than some had thought. Yet the technology to allow such communication exists. If devices could talk to one another over the Internet, we could have a world of smart houses and smart offices. (Fiona Harvey, The Financial Times, 24 March 2004. © The Financial Times. All rights reserved)

What stimulates this apparently insatiable appetite [for taking control of our health]? Some polemicists argue that, in an age of uncertainty and political impotence, the governance of our health and the reshaping of our anatomy is the only ‘power’ that punters can wield. It is also the offshoot of both a mistrust of the medical profession and its demystification – witnessed, for instance, in parents who refuse the MMR vaccination for their children, regardless of how much doctor insists that he knows best. Public health campaigns are a whole lot trickier now that the patient no longer swallows large doses of paternalism. (Yvonne Roberts, New Statesman special supplement on health, 24 June 2004)

… three years ago, plants with leaf blemishes and dying stems started turning up in British nurseries and garden centres. The fungus causing this was … found to be P. ramorum. Diseased plants were destroyed by officials from the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (defra), but the British version of Sod [sudden oak death], called ramorum, has now been spotted in more than 300 places. Ominously, it has jumped the garden centre fence and appeared in at least nine mature trees in three gardens in Cornwall, a witch-hazel in Wales and an isolated American red oak in Sussex. (Paul Evans, The Guardian Environment, 11 February 2004)

To gain a place on the main board of a public company is the equivalent of a lottery win. Put another way, it gives you access to the bran tub that is shareholders’ funds. A huge salary is only the beginning. Now that it is compulsory for companies to reveal much more about their remuneration policies, bemused shareholders are discovering for the first time the extent of their unwitting generosity.

It is not uncommon for directors to have a house in central London on the firm, to have school fees paid, to get free dental and medical treatment, and, for all I know, hair and clothes allowances too. All that, of course, comes on top of lavish share options and pension provisions.

Best of all, however, is that should things go terribly wrong and prove that the pampered voluptuary whom you appointed to the board at immense cost was in fact an overstuffed turkey, he or she still wins. The reward for failure is usually the equivalent of two or three years’ salary plus a continuing pension – a system that makes millionaires out of duds. (Iain Murray, Money Observer, June 2003)