1

Characteristics of the medium

From its first tentative experiments and the early days of wireless, radio has expanded into an almost universal medium of communication. It leaps around the world on short waves linking the continents in a fraction of a second. It jumps to high satellites to put its footprint across a quarter of the globe. It brings that world to those who cannot read and helps maintain a contact for those who cannot see.

It is used by armies in war and by amateurs for fun. It controls the air lanes and directs the taxi. It is the enabler of business and commerce, the essential for fire brigades and police, the commonplace of the mobile phone. Broadcasters pour out millions of words every minute in an effort to inform, educate and entertain, propagandize and persuade; music fills the air. Community radio makes broadcasters out of listeners and the Citizen Band gives transmitter power to the individual.

Whatever else can be said of the medium, it is plentiful. It has lost the sense of awe which attended its early years, becoming instead a very ordinary and ‘unspecial’ method of communication. To use it well we may have to adapt the formal ‘written’ language which we learnt at school and rediscover our oral traditions. How the world might have been different had Guglielmo Marconi lived before Johann Gutenberg.

To succeed in a highly competitive marketplace where television, lifestyle magazines, newspapers, cinema, theatre, websites, DVDs and CDs jostle for the attention of a media-conscious public, the radio producer must first understand the strengths and weaknesses of radio and make some comparisons with other media.

Radio makes pictures

It is a blind medium but one which can stimulate the imagination so that, as soon as a voice comes out of the loudspeaker, the listener attempts to visualize the source of the sound and to create in the mind's eye the owner of the voice. What pictures are created when the voice carries an emotional content – interviews with witnesses of a bomb blast – the breathless joy of a victorious sports team.

Unlike television, where the pictures are limited by the size of the screen, radio's pictures are any size you care to make them. For the writer of radio drama it is easy to involve us in a battle between goblins and giants, or to have our spaceship land on a strange and distant planet. Created by appropriate sound effects and supported by the right music, virtually any situation can be brought to us. As the schoolboy said when asked about television drama, ‘I prefer radio, the scenery is so much better.’

But is it more accurate? Naturally, a visual medium has an advantage when demonstrating a procedure or technique, and a simple graph is worth many words of explanation. In reporting an event there is much to be said for seeing video of, say, a public demonstration rather than leaving it to our imagination. Both sound and vision are liable to the distortions of selectivity, and in news reporting it is up to the integrity of the individual on the spot to produce as fair, honest and factual an account as possible. In the case of radio, its great strength of appealing directly to the imagination must not become the weakness of allowing individual interpretation of a factual event, let alone the deliberate exaggeration of that event by the broadcaster. The radio writer and commentator chooses words with precision so that they create appropriate pictures in the listener's mind, making the subject understood and its occasion memorable.

Radio speaks to millions

Radio is one of the mass media. The very term broadcasting indicates a wide scattering of the output covering every home, village, town, city and country within the range of the transmitter. Its potential for communication therefore is very great, but the actual effect may be quite small. The difference between potential and actual will depend on matters to which this book is dedicated – programme relevance, editorial excellence and creativity, qualities of ‘likeability’ and persuasiveness, operational competence, technical reliability, and consistency of the received signal. It will also be affected by the size and strength of the competition in its many forms. Broadcasters sometimes forget that people have other things to do – life is not all about listening to radio and watching television.

Audience researchers talk about share and reach. Audience share is the amount of time spent listening to a particular station, expressed as a percentage of the total radio listening in its area. Audience reach is the number of people who do listen to something from the station over the period of a day or week, expressed as a percentage of the total population who could listen. Both figures are significant. A station in a highly competitive environment may have quite a small share of the total listening, but if it manages to build a substantial following to even one of its programmes, let alone the aggregate of several minorities, it will enjoy a large reach. The mass media should always be interested in reach.

Radio speaks to the individual

Unlike television, where the viewer is observing something coming out of a box ‘over there’, the sights and sounds of radio are created within us, and can have greater impact and involvement. Radio on headphones happens literally inside your head. Television is, in general, watched by small groups of people and the reaction to a programme is often affected by the reaction between individuals. Radio is much more a personal thing, coming direct to the listener. There are obvious exceptions: communal listening happens in garages, workshops, canteens and shops, and in the rural areas of less developed countries a whole village may gather round the set. However, even here, a radio is an everyday personal item.

The broadcaster should not abuse this directness of the medium by regarding the microphone as an input to a public address system, but rather a means of talking directly to the individual – multiplied tens of thousands, perhaps millions, of times.

The speed of radio

Technically uncumbersome, the medium is enormously flexible and is often at its best in the totally immediate ‘live’ situation. No waiting for the presses or the physical distribution of newspapers or magazines. A news report from a correspondent overseas, a listener talking on the phone, a sports result from the local stadium, a concert from the capital – radio is immediate. The recorded programme introduces a timeshift and like a newspaper may quickly become out of date, but the medium itself is essentially live and ‘now’.

The ability to move about geographically generates its own excitement. Long since regarded as a commonplace, both for television and radio, pictures and sounds are beamed and bounced around the world, bringing any event anywhere to our immediate attention. Radio speeds up the dissemination of information so that everyone – the leaders and the led – knows of the same news event, the same political idea, declaration or threat. If knowledge is power, radio gives power to us all whether we exercise authority or not.

Radio has no boundaries

Books and magazines can be stopped at national frontiers but radio is no respecter of territorial limits. Its signals clear mountain barriers and cross deep oceans. Radio can bring together those separated by geography or nationality – it can help to close other distances of culture, learning or status. The programmes of political propagandists or of Christian missionaries can be sent in one country and heard in another. Sometimes met with hostile jamming, sometimes welcomed as a life-sustaining truth, programmes have a liberty independent of lines on a map, obeying only the rules of transmitter power, sunspot activity, channel interference and receiver sensitivity. Even these limitations are overcome for radio on the Internet, which can bring any station to an Internet-enabled PC, laptop or WAP mobile phone, wherever it is. Independent of transmitter power or cable networks, any studio can have a worldwide reach. Crossing political boundaries, radio can bring freedoms to the oppressed and enlightenment to those in darkness.

The transient nature of radio

It is a very ephemeral medium and if the listener is not in time for the news bulletin, it is gone and it's necessary to wait for the next. Unlike the newspaper, which the reader can put down, come back to or pass round, broadcasting imposes a strict discipline of having to be there at the right time. The radio producer must recognize that, while it's possible to store programmes in the archives, they are only short-lived for the listener. This is not to say that they may not be memorable, but memory is fallible and without a written record it is easy to be misquoted or taken out of context. For this reason, it is often advisable for the broadcaster to have some form of audio or written log as a check on what was said, and by whom. In some cases this may be a statutory requirement of a radio station as part of its public accountability. Where this is not so, lawyers have been known to argue that it is better to have no record of what was said – for example, in a public phone-in. Practice would suggest, however, that the keeping of a recording of the transmission is a useful safeguard against allegations of malpractice, particularly from complainants who missed the broadcast and who heard about it second-hand.

The transitory nature of the medium means that the listener must not only hear the programme at the time of its broadcast, but must also understand it then. The impact and intelligibility of the spoken word should occur on hearing it – there is seldom a second chance. The producer must therefore strive for the utmost logic and order in the presentation of ideas, and the use of clearly understood language.

Radio on demand

Radio on the Internet has the very great advantage of not only being available live and ‘now’, but of extending the life of previous programmes, news bulletins and features so they can be recalled on demand. By offering audio files of earlier material, the station website overcomes the essentially ephemeral nature of broadcasting in that it provides specific listening when the listener wants it, not simply when it happens to be broadcast. Internet use of radio in this way radically changes the medium, transferring the scheduling power from the station to the listener. Downloaded, of course, programmes can be kept permanently.

Radio as background

Radio allows a more tenuous link with its user than that insisted upon by television or print. The medium is less demanding in that it permits us to do other things at the same time – programmes become an accompaniment to something else. We read with music on, eat to a news magazine, or hang wallpaper while listening to a play. Radio suffers from its own generosity – it is easily interruptible. Television is more complete, taking our whole attention, ‘spoonfeeding’ without demanding effort or response, and tending to be compulsive at a far lower level of interest than radio requires of its audience.

Because radio is so often used as background, it frequently results in a low level of commitment on the part of the listener. If the broadcaster really wants the listener to do something – to act – then radio should be used in conjunction with another medium. Educational broadcasting, for example, needs printed fact-sheets, booklet material and tutor hot-lines involving schools or universities. Radio evangelism has to be linked with follow-up correspondence and involve local churches or on-the-ground missionaries. Advertising requires appropriate recall and point-of-sale material. While radio can claim some spectacular individual action results, in general, producers have to work very hard to retain their part-share of the listener's attention.

Radio is selective

There is a different kind of responsibility on the broadcaster from that of the newspaper editor in that the radio producer selects exactly what is to be received by the consumer. In print, a large number of news stories, articles and other features are set out across several pages. Each one is headlined or identified in some way to make for easy selection. The reader scans the pages, choosing to read those items of particular interest – using his or her own judgement. With radio this is not possible. The selection process takes place in the studio and the listener is presented with a single thread of material; it is a linear medium. Choice for the listener exists only in the mental switching-off which occurs during an item that fails to maintain interest, or when actively tuning to another station. In this respect, a channel of radio or television is rather more autocratic than a newspaper.

Radio lacks space

A newspaper may carry 30 or 40 columns of news copy – a 10-minute radio bulletin is equivalent to a mere column and a half. Again, the selection and shaping of the spoken material has to be tighter and more logical. Papers can devote large amounts of space to advertisements, particularly to the ‘small ads’, and personal announcements such as births, deaths and marriages. This is ideal scanning material and it is not possible to provide such detailed coverage in a radio programme.

A newspaper is able to give an important item additional impact simply by using more space. The big story is run using large headlines and bold type – the picture is blown up and splashed across the front page. The equivalent in a radio bulletin is to lead with the story and to illustrate it with a voice report or interview. There is a tendency for everything in the broadcast media to come out of the set the same size. An item may be run longer but this is not necessarily the same as ‘bigger’. Coverage described as ‘in depth’ may only be ‘at length’. There is limited scope for indicating the differing importance of an economic crisis, a religious item, a murder, the arrival of a pop group, the market prices and the weather forecast. It could be argued that the press is more likely to use this ability to emphasize certain stories to impose its own value judgements on the consumer. This naturally depends on the policy of the individual newspaper editor. The radio producer is denied the same freedom of manoeuvre and this can lead to the feeling that all subjects are treated in the same way, a criticism of bland superficiality not infrequently heard. On the other hand, this characteristic of radio perhaps restores the balance of democracy, imposing less on the listener and allowing greater freedom of judgement as to what is important.

The personality of radio

A great advantage of an aural medium over print lies in the sound of the human voice – the warmth, the compassion, the anger, the pain and the laughter. A voice is capable of conveying much more than reported speech. It has inflection and accent, hesitation and pause, a variety of emphasis and speed. The information which a speaker imparts is to do with the style of presentation as much as the content of what is said. The vitality of radio depends on the diversity of voices which it uses and the extent to which it allows the colourful turn of phrase and the local idiom.

It is important that all kinds of voices are heard and not just those of professional broadcasters, power holders and articulate spokesmen. The technicalities of the medium must not deter people in all walks of life from expressing themselves with a naturalness and sincerity which reflects their true personalities. Here radio, uncluttered by the pictures which accompany the talk of television, is capable of great sensitivity, and of engendering great trust.

The simplicity of radio

The basic unit comprises one person with a microphone and recorder rather than even a small TV crew. This encourages greater mobility and also makes it easier for the non-professional to take part, thereby enlarging the possibilities for public access to the medium. In any case, sound is better understood than vision, with on-line radio, cassette players and stereo equipment found in most schools and homes. While the amateur video diary is an accepted format, far more complex programme ideas can be well executed by part-timers in radio. It is also probably true that whereas with television or print any loss of technical standards becomes immediately obvious and unacceptable, with radio there is a recognizable margin between the excellent and the adequate. This is not to say that one should not continually strive for the highest possible radio standards, simply that sound is easier to work with for the non-specialist.

For the broadcaster, radio's comparative simplicity means a flexibility in its scheduling. Items within programmes, or even whole programmes, can be dropped to be replaced at short notice by something more urgent.

Figure 1.1 A small wind-up radio for use where batteries are expensive or unobtainable. It also has a torch light and will charge a mobile phone. A ‘fun’ DAB radio called ‘The Bug’ is also shown. This has a screen that provides additional information by scrolling text, and a solid state recording facility enabling the listener to put a programme on ‘pause’ for up to 20 minutes

Radio is low cost

Relative to the other media, both its capital cost and its running expenses are small. As broadcasters round the world have discovered, the main difficulty in setting up a station is often not financial but lies in obtaining a transmission frequency. Such frequencies are safeguarded by governments as signatories to international agreements; they are finite, a limited resource, and are not easily assigned. A free for all would lead to chaos on the air.

However, because the medium is cheap to use and can attract a substantial audience, the cost per hour – or more significantly the cost per listener hour – is low. Such figures have to be provided for advertisers, sponsors, supporters and accountants. But it is also important for the producer as well as the executive manager to know what a programme costs relative to its audience. This is not to say that cost-effectiveness is the only measure of worth – it most certainly is not – but it is one of the factors which inform scheduling decisions.

The relatively low cost once again means that the medium is ideal for use by the non-professional. Because time is not so expensive or so rare, radio stations – unlike their television counterparts – are encouraged to take a few gambles in programming. Radio is a commodity which cannot be hoarded, neither is it so special that it cannot be used by anyone with something interesting to say. Through all sorts of methods of listener participation, the medium is capable of offering a role as a two-way communicator, particularly in the area of community broadcasting.

Radio can reduce its costs still further by using an automated playout system whereby the station provides a full output schedule without anyone being present to oversee the transmission. This is particularly useful for regular half-hour blocks of programming or to cover the night time, although some stations operate an automated playout system for the entire day.

Radio is also cheap for the listener. The development of printed circuit boards and solid state technology has allowed sets to be mass produced at a cost which enables their virtual total distribution. Where batteries are expensive, a set may operate with a wind-up clockwork motor. More affordable than a set of books, good radio brings its own ‘library’, which is of special value to those who for whatever reason are deprived of literature in their own language. The broadcaster should never forget that, while it's easy to regard the technical installations (studios, transmitters, etc.) as expensive, the greater part of the total capital cost of any broadcasting system is borne directly by the public in buying receivers.

Radio for the disadvantaged

Because of its relatively low cost and because it doesn't require the education level of literacy, radio is particularly well suited to meet the needs of the poor and disadvantaged. The UK Government's Department for International Development sets special store in using radio. Their booklet, The Media in Governance, says:

‘The news media can be used to convince the poor of the benefits of having and realizing rights – and can help them assert these rights in practice. In many countries this is best achieved through radio which reaches a wide audience, rather than television which may be accessible to only a small minority.’

Radio teaches

Radio works particularly well in the world of ideas. As a medium of education it excels with concepts as well as facts. From dramatically illustrating an event in history to pursuing current political thought, it has a capability with any subject that can be discussed, taking the learner at a predetermined pace through a given body of knowledge. With musical appreciation and language teaching it is totally at home. Of course, it lacks television's ability to demonstrate and show, it does not have charts and graphs – as a medium it is more literate than numerate – but backed up by a teacher's notes even these limitations can be overcome and a booklet helps to give memory to the understanding. Add the correspondence element and you have the two-way questioning process which is at the heart of all personal learning.

From Australia's ‘School of the Air’ to the UK's ‘Open University’, radio effectively reaches out to meet the formal and informal learning needs of people who want to grow.

Radio has music

Here are the Beethoven symphonies, the top 40, tunes of our childhood, jazz, opera, rock and favourite shows. From the best on CD to a quite passable local church organist, radio provides the pleasantness of an unobtrusive background or the focus of our total absorption. It relaxes and stimulates, inducing pleasure, nostalgia, excitement or curiosity. The range of music is wider than the coverage of the most comprehensive record library and can therefore give the listener a chance to discover new or unfamiliar forms of music.

DAB radio enhances the experience by supplying a range of additional information, such as station name, music title, artist and any special messages the station wants to send. It is also receivable through a digital TV set or set-top box, so multiplying the outlets for a programme. This also has the advantage of easy recording of radio using an associated video or DVD recorder, or personal ‘Time Shift’ hard disk recorder.

Radio can surprise

Unlike the CD we play or the book we pick up at home, selected to match our taste and feelings of the moment, music and speech on radio is chosen for us and may, if we let it, change our mood and take us out of ourselves. We can be presented with something new and enjoy a chance encounter with the unexpected. Radio should surprise. Broadcasters are tempted to think in terms of format radio, where the content lies precisely between narrowly defined limits. This gives consistency and enables the listener to hear what is expected, which is probably why the radio is switched on in the first place. But radio can also provide the opportunity for innovation and experiment – a risk that producers must take if the medium is to surprise us in a way which is both creative and stimulating.

Radio can suffer from interference

While a newspaper or magazine is normally received in exactly the form in which it was published, radio has no such automatic guarantee. Shortwave transmission is frequently subject to deep fading and co-channel interference. Medium wave too, especially at night, may suffer from the intrusion of other stations. The quality of the sound received is likely to be very different in its dynamic or frequency range from the carefully produced balance heard in the studio. Even FM, which can be temperamental, is liable to a range of distortions, from the flutter caused by a passing aeroplane to ignition interference from cars and other electrical equipment.

Reception in a moving vehicle can also be difficult as the signal strength varies. Digital transmission (DAB) and direct broadcasting by satellite overcome most of these problems – at a cost – but it is as well for the producer to remember that what leaves the studio is not necessarily what is heard in the possibly noisy environment of the listener. Difficult reception conditions require compelling programmes in order to retain a faithful audience.

Given these 18 basic characteristics of the medium, how is radio to be used? What are its possibilities? Details vary across the world, but broadly it functions in two main ways – it serves the individual and operates on behalf of society as a whole.

Radio for the individual

![]() It diverts people from their problems and anxieties, providing relaxation and entertainment. It reduces feelings of loneliness, creating a sense of companionship.

It diverts people from their problems and anxieties, providing relaxation and entertainment. It reduces feelings of loneliness, creating a sense of companionship.

![]() It is the supplier or confirmer of local, national or international news, and establishes for us a current agenda of issues and events. It satisfies our personal curiosity about what is going on.

It is the supplier or confirmer of local, national or international news, and establishes for us a current agenda of issues and events. It satisfies our personal curiosity about what is going on.

![]() It offers hope and inspiration to those who feel isolated or oppressed within a restrictive environment, or where their own media are manipulated or suppressed.

It offers hope and inspiration to those who feel isolated or oppressed within a restrictive environment, or where their own media are manipulated or suppressed.

![]() It helps to solve problems by acting as a source of information and advice. It can do this either through direct personal access to the programme or in a general way by indicating sources of further help.

It helps to solve problems by acting as a source of information and advice. It can do this either through direct personal access to the programme or in a general way by indicating sources of further help.

![]() It enlarges personal ‘experience’, stimulating interest in previously unknown topics, events or people. It promotes creativity and can point towards new personal activity. It meets individual needs for formal and informal education.

It enlarges personal ‘experience’, stimulating interest in previously unknown topics, events or people. It promotes creativity and can point towards new personal activity. It meets individual needs for formal and informal education.

![]() It contributes to self-knowledge and awareness, offering security and support. It enables us to see ourselves in relation to others, and links individuals with leaders and ‘experts’.

It contributes to self-knowledge and awareness, offering security and support. It enables us to see ourselves in relation to others, and links individuals with leaders and ‘experts’.

![]() It guides social behaviour, setting standards and offering role models with which to identify.

It guides social behaviour, setting standards and offering role models with which to identify.

![]() It aids personal contacts by providing topics of conversation through shared experience – ‘did you hear the programme last night?’

It aids personal contacts by providing topics of conversation through shared experience – ‘did you hear the programme last night?’

![]() It enables individuals to exercise choice, to make decisions and act as citizens, especially in a democracy through the unbiased dissemination of news and information.

It enables individuals to exercise choice, to make decisions and act as citizens, especially in a democracy through the unbiased dissemination of news and information.

Radio for society

![]() It acts as a multiplier of change, speeding up the process of informing a population, and heightening an awareness of key issues.

It acts as a multiplier of change, speeding up the process of informing a population, and heightening an awareness of key issues.

![]() It provides information about jobs, goods and services, and so helps to shape markets by providing incentives for earning and spending.

It provides information about jobs, goods and services, and so helps to shape markets by providing incentives for earning and spending.

![]() It acts as a watchdog on power holders, providing contact between them and the public.

It acts as a watchdog on power holders, providing contact between them and the public.

![]() It helps to develop agreed objectives and political choice, and enables social and political debate, exposing issues and options for action.

It helps to develop agreed objectives and political choice, and enables social and political debate, exposing issues and options for action.

![]() It acts as a catalyst and focus for celebration – or mourning – enabling individuals to act together, forming a common consciousness.

It acts as a catalyst and focus for celebration – or mourning – enabling individuals to act together, forming a common consciousness.

![]() It contributes to the artistic and intellectual culture, providing opportunities for new and established performers of all kinds.

It contributes to the artistic and intellectual culture, providing opportunities for new and established performers of all kinds.

![]() It disseminates ideas. These may be radical, leading to new beliefs and values, so promoting diversity and change – or they may reinforce traditional values, so helping to maintain social order through the status quo.

It disseminates ideas. These may be radical, leading to new beliefs and values, so promoting diversity and change – or they may reinforce traditional values, so helping to maintain social order through the status quo.

![]() It enables individuals and groups to speak to each other, developing an awareness of a common membership of society.

It enables individuals and groups to speak to each other, developing an awareness of a common membership of society.

![]() It mobilizes public and private resources for personal or community ends, particularly in an emergency.

It mobilizes public and private resources for personal or community ends, particularly in an emergency.

Some of these functions are in mutual conflict, some are applicable more to a local rather than a national community, and some apply fully only in conditions of crisis. However, the programme producer should be clear about what it is he or she is trying to achieve. Lack of clarity about a programme's purpose leads to a fuzzy, ineffective end product – it also leads to arguments in the studio over what should and should not be included. We shall return to the point, but it is not enough for the producer to want to make an excellent programme – you might as well want merely to modulate the transmitter. The question is why? What is to be its effect – on the listener, that is? Before looking at some possible personal motivations for making programmes at all, we should examine the meaning of the much-used phrase: broadcasting as a public service.

The public servant

Public service broadcasting is sometimes regarded as an alternative to commercial radio. The terms are not mutually exclusive, however; it is possible to run commercial radio as a public service, especially in near-monopoly conditions or where there is little competition for the available advertising. It is a matter of where the radio managers see their first loyalty. To put this in perspective, here are 10 attributes of service, using the analogy of the perfect domestic servant. He or she:

![]() is loyal to the employer and does not try to serve other interests or use this position of privilege for personal gain. Servants are clear about their purpose and demonstrate this in everything they do.

is loyal to the employer and does not try to serve other interests or use this position of privilege for personal gain. Servants are clear about their purpose and demonstrate this in everything they do.

![]() understands the culture, nuances and foibles of the family being served, and in accepting them also becomes fully accepted. The servant is not critical or judgemental of those he or she serves, but may challenge them or even restrain them. But the servant is not a policeman, there is no corrective mandate.

understands the culture, nuances and foibles of the family being served, and in accepting them also becomes fully accepted. The servant is not critical or judgemental of those he or she serves, but may challenge them or even restrain them. But the servant is not a policeman, there is no corrective mandate.

![]() is available when needed, and for whoever in the family needs help, the young and the old as well as the head of the house. It may be tempting to pay court to the power holders, to keep in with the paymaster – but it could be the children, the sick or disadvantaged who need most attention.

is available when needed, and for whoever in the family needs help, the young and the old as well as the head of the house. It may be tempting to pay court to the power holders, to keep in with the paymaster – but it could be the children, the sick or disadvantaged who need most attention.

![]() is actually useful, meeting stated requirements and anticipating needs and difficulties – ready to offer original solutions to problems, as or even before they arrive. The servant looks ahead and is creative.

is actually useful, meeting stated requirements and anticipating needs and difficulties – ready to offer original solutions to problems, as or even before they arrive. The servant looks ahead and is creative.

![]() is well informed, knows what's going on, offers good advice and is able to relate unpalatable truth, risking unpopularity in the process. The servant therefore has courage as well as a well-stocked mind.

is well informed, knows what's going on, offers good advice and is able to relate unpalatable truth, risking unpopularity in the process. The servant therefore has courage as well as a well-stocked mind.

![]() is hard working, technically expert and efficient. Does not waste resources but is honest and open, and if called to account for particular behaviour, responds willingly. There is nothing underhand – integrity is a key attribute.

is hard working, technically expert and efficient. Does not waste resources but is honest and open, and if called to account for particular behaviour, responds willingly. There is nothing underhand – integrity is a key attribute.

![]() is witty and companionable, courteous and punctual. The servant inhabits our house, comes with us in the car, and is someone with whom we can have a relationship that is enjoyable as well as professional.

is witty and companionable, courteous and punctual. The servant inhabits our house, comes with us in the car, and is someone with whom we can have a relationship that is enjoyable as well as professional.

![]() has to realize, especially in a large family, that it's not possible to do everything, to be in two places at once – there are priorities. The family must understand this too.

has to realize, especially in a large family, that it's not possible to do everything, to be in two places at once – there are priorities. The family must understand this too.

![]() works smoothly alongside others and does not crave recognition or status. When the number to be served is very large, other servants may need to be brought in. We may want to contract out some of the work to specialists – a governess, cook, chauffeur, gardener.

works smoothly alongside others and does not crave recognition or status. When the number to be served is very large, other servants may need to be brought in. We may want to contract out some of the work to specialists – a governess, cook, chauffeur, gardener.

![]() is affordable. My servant must not bankrupt me. However much I value this service, long-term cost-effectiveness is crucial.

is affordable. My servant must not bankrupt me. However much I value this service, long-term cost-effectiveness is crucial.

Each of these characteristics of service has its equivalent in public service broadcasting. Its hallmarks can be drawn from our ideas of what a servant is and does. Such a station is certainly not arrogant, setting itself up as a power in its own right. It is responsive to need, making itself available for everyone – not simply the rich and powerful. Indeed, its universality makes a point of including the disadvantaged. It is wide ranging in its appeal, competent and reliable, entertaining and informative. Its programmes for minorities are not to be hidden away in the small hours but are part of the diversity available at prime time. It is popular in that over a period of time it reaches a significant proportion of the population. It does not ‘import’ its programmes from ‘foreign’ sources but is culturally in tune with its audience, producing most of the output itself. It provides useful and necessary things – things of the quality asked for, but also unexpected pleasures. Above all, it is editorially free from interference by political, commercial or other interests, serving only one master to whom it remains essentially accountable – its public.

But there is an immediate dilemma – such perfection may be too expensive. As in everything else, we get the level of service we pay for and it may not be possible to afford a 24 hours a day, seven days a week output catering for all needs. Live concerts, stereo drama and world news are expensive commodities, and radio managers need to make judgements about what can be provided at an acceptable price.

The concept works well for a service that is adequately paid for by its listeners – by public licence or by subscription. But if this is not the case, can a public service station do deals with third parties to raise additional revenue? Can a government, commercial or religious station be run as a genuine public service? Yes it can, but the difficulties are obvious.

First, a publicly funded service which makes arrangements with commercial interests is putting its first loyalty, its editorial integrity, at risk. Any producer making a programme as a co-production, or acting under special rules, must say so – not as part of some secret or unstated pay-off, but to meet the requirements of public service accountability.

Second, there is a strong tendency for ‘piper payers’ to want to call the tune. A government does not like to hear criticism of its policy on a station which it regards as its own. Authority, in general, does not wish to be challenged – as from time to time political interviewers must. Ministries and departments are highly sensitive to items which ‘in the public interest’ they would rather not have broadcast. Officials will avoid or delay ‘bad news’, however true. Similarly, a commercial station often needs to maximize its audience in order to justify the rates – certainly at peak times – so pushing sectional interests to one side to satisfy the advertisers’ desire for mass popularity. A Christian fund-raising constituency may press for the gospel it wants to hear, forgetting the need to serve people in a multiplicity of ways. The need to survive in a harsh political climate, or in a fiercely competitive one, exacerbates these pressures. The fact is that a station dedicated to public service but controlled or funded by a third party, having its own agenda and interests to consider, is almost certain to weaken in its commitment.

Types of radio station

Radio is categorized not so much by what it does as by how it is financed. Each method of funding has a direct result on the programming that a station can afford or is prepared to offer, which again is affected by the degree of competition which it faces.

The main types of organizational funding are as follows:

![]() Public service, funded by a licence fee and run by a national corporation.

Public service, funded by a licence fee and run by a national corporation.

![]() Commercial station financed by national and local spot advertising or sponsorship, and run as a public company with shareholders.

Commercial station financed by national and local spot advertising or sponsorship, and run as a public company with shareholders.

![]() Government station paid for from taxation and run as a government department.

Government station paid for from taxation and run as a government department.

![]() Government-owned station, funded largely by commercial advertising, operating under a government appointed board.

Government-owned station, funded largely by commercial advertising, operating under a government appointed board.

![]() Public service, funded by government funds or grant-in-aid, run by a publicly accountable board, independent of government.

Public service, funded by government funds or grant-in-aid, run by a publicly accountable board, independent of government.

![]() Public service, subscription station, does not take advertising and is funded by individual subscribers and donors.

Public service, subscription station, does not take advertising and is funded by individual subscribers and donors.

![]() Private ownership, funded by personal income of all kinds, e.g. commercial advertising, subscriptions, donations.

Private ownership, funded by personal income of all kinds, e.g. commercial advertising, subscriptions, donations.

![]() Institutional ownership, e.g. university campus, hospital or factory radio, run and paid for by the organization for the benefit of its students, patients, employees, etc.

Institutional ownership, e.g. university campus, hospital or factory radio, run and paid for by the organization for the benefit of its students, patients, employees, etc.

![]() Radio organization run for specific religious or charitable purposes – sells airtime and raises income through supporter contributions.

Radio organization run for specific religious or charitable purposes – sells airtime and raises income through supporter contributions.

![]() Community ownership, often supported by local advertising and sponsors.

Community ownership, often supported by local advertising and sponsors.

![]() Restricted Service Licence (RSL) stations, on low power and having a limited lifespan to meet a particular need, e.g. one-month licence to cover a city festival.

Restricted Service Licence (RSL) stations, on low power and having a limited lifespan to meet a particular need, e.g. one-month licence to cover a city festival.

The ability to charge premium rates for advertising depends either on having a large audience in response to popular appeal programming or an audience with a high purchasing power for the individual advertiser. Competing for income from a limited supply is quite different from the competition which a station has to win an audience.

Around the world, stations combine different forms of funding and supplement their income by all possible means, from profit-making events such as concerts, publishing and the sale of programmes – both to the public on CDs and cassettes, as well as to other broadcasters, to the sale of T-shirts, community coffee mornings and car boot sales.

‘Outside’ pressures

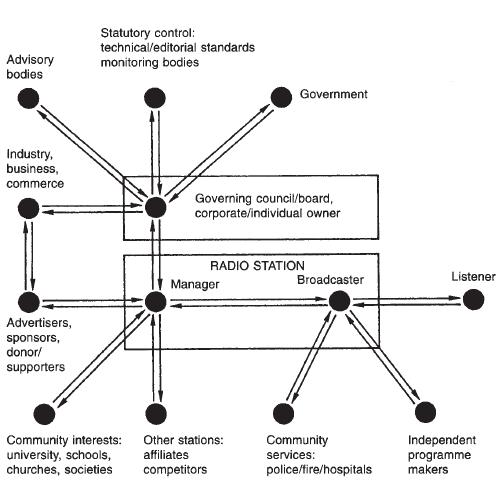

No radio station – and therefore no producer – exists in a vacuum. It has a context of connections, each one useful and necessary but also representing a source of potential pressure which can inhibit a single-minded commitment to the ideal of public service. Figure 1.2 illustrates some of these, each linked by two directional arrows. It is an important exercise for broadcasters to know in their own situation what these arrows represent. What are the expectations and transactions in each direction? Does money change hands? Is information exchanged? To what extent are these expectations fulfilled? For the individual producers the compromises and strictures of their own management are difficult enough; additional obligations to interests outside broadcasting can be extremely tiresome. Nevertheless, as a background to programme making it is necessary to be aware of everyone else who has a stake in the process.

Figure 1.2 The context of a radio station – typical links and pressure points

For example, the working producer should know at least two members of the organization's governing board or council. Not only does this help the programme makers to appreciate the context within which the station is operating, but also acquaints board members with the difficulties and encouragements experienced by those who actually create the product. Such introductions are best made through the manager.

Personal motivations

So what is our purpose for being in radio? Is it because it has some appearance of power – able to sway public opinion and make people do things? If so, it has to be said that this is very rare and most unlikely to be achieved by this medium alone. Is it to be the protagonist mouthpiece of someone else – or are there reasons which meet my own needs?

It is as well for the producer to understand what some of these personal motivations are:

![]() to inform people – the role of the media journalist

to inform people – the role of the media journalist

![]() to educate – enabling people to acquire knowledge or skill

to educate – enabling people to acquire knowledge or skill

![]() to entertain – making people laugh, relax or pass the time agreeably

to entertain – making people laugh, relax or pass the time agreeably

![]() to reassure – providing supportive companionship

to reassure – providing supportive companionship

![]() to shock – the sensation station

to shock – the sensation station

![]() to make money – a means of earning a living

to make money – a means of earning a living

![]() to enjoy oneself – a means of artistic expression

to enjoy oneself – a means of artistic expression

![]() to create change – crusading for a new society

to create change – crusading for a new society

![]() to preserve the status quo – returning to established values

to preserve the status quo – returning to established values

![]() to convert to one's own belief – proselytizing a faith

to convert to one's own belief – proselytizing a faith

![]() to present options – assisting citizenship, allowing the listener to exercise choice.

to present options – assisting citizenship, allowing the listener to exercise choice.

Each programme maker must ask ‘Why do I want to be in broadcasting?’ Is it just a job? Certainly it may be in order to earn a living, but also because he or she has something to say. It may be out of a genuine desire to serve one's fellow men and women – to provide options for action by opening up possibilities, entertaining people, making them better informed, or something to do with ‘truth’. Perhaps it's a more complicated amalgam than any of these.

One's success criteria are perhaps best summed up as a response to the question ‘What do you want to say, to whom, and with what effect?’ The ‘to whom?’ is important for, in the end, radio is about a relationship. Much more than on television, the presenter, DJ or newsreader can establish a sense of rapport with the listener.

The successful station is more than the sum of its programmes, it understands and values the nature of this relationship – and the role which it has for its community as both leader and servant.