1

View Cameras

1.1 View Cameras

Modern view cameras are the descendants of many generations of large-format cameras, dating back to the birth of photography in 1839 with the introduction of the daguerreotype process. The first commercially manufactured daguerreotype camera, designed by Daguerre and manufactured by Giroux in 1839, was a two-part wood box with the lens mounted on the outer front box and the ground glass attached to the inner back box, which could be moved back and forth to focus the image (Figure 1-1). A pivoted disk in front of the lens served as a shutter, and a 45° mirror behind the ground glass provided an upright but laterally reversed reflection of the inverted ground-glass image.1

The desire on the part of photographers for camera modifications to meet specific picture-making needs resulted in improvements such as substitution of a flexible bellows for the sliding boxes and the tilt, swing, and shift adjustments on the lens and ground glass that are features of modern view cameras. The desire for camera modifications also generated, over the years, a whole range of other types of cameras, including large-format cameras that could be handheld (thanks to the addition of an optical viewfinder for composing and a coupled rangefinder for focusing), roll-film box cameras, and 35-mm cameras. Introduction of the Exakta 35-mm single-lens reflex (SLR) camera in 1936 and the Zeiss Contax 35-mm SLR with a pentaprism for eye-level viewing in 1949, combined with the continuing improvements in the graininess of 35-mm film, led many to predict the demise of large-format cameras.2 Newspaper photographers, indeed, did switch from 4 × 5-in. press cameras to 35-mm SLR cameras as rapidly as they could talk management into purchasing new cameras. The 35-mm SLR cameras also became very popular with advanced amateur photographers and photojournalists, while the larger roll-film SLR cameras became popular with fashion photographers and some other professional photographers who wanted a compromise between the image quality produced with large-format cameras and the convenience of small-format cameras.

To the surprise of many, however, the popularity of view cameras, rather than declining, actually increased along with that of the smaller-format cameras. Surveys of the number of different models of view cameras available in the United States in 1967 and in 1993 revealed that the number of models of 4 × 5-in. view cameras increased from 16 to 49; when including smaller-format and larger-format view cameras, the total number of different view cameras increased from 34 to 90.3 This edition lists 112 different models, not counting 5 × 7-in. cameras—which typically have the same features as a corresponding 4 × 5-in. or 8 × 10-in. model—or cameras with formats larger than 11 × 14 in.

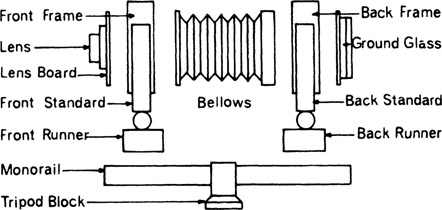

View cameras can generally be classified as being of either flatbed (Figure 1-2) or monorail construction. Most of the early view cameras were of the flatbed variety, although a wood monorail camera is known to have been made by 1870. In recent decades more models of monorail cameras than flatbed cameras have been marketed. Flatbed cameras generally are constructed of wood. Most can be folded into a compact, self-contained carrying case, an advantage when traveling with a view camera. Monorail view cameras are generally constructed of metal, and many are modular in design, which permits considerable flexibility in modifying the camera to meet special needs. An exploded view of a generic monorail view camera, with the parts identified, is shown in Figure 1-3. Not all monorail view cameras can be disassembled as completely as indicated in the exploded view, but the trend is in that direction.

Figure 1-1

Daguerreotype camera designed by Daguerre and manufactured by Giroux in 1839.

Figure 1-2

Flatbed view cameras typically have wood frames, are relatively light in weight, and can be folded into a compact self-contained case with a carrying handle.

In addition to the camera, a few accessories are considered to be essential. These include a tripod (or camera stand), a focusing cloth or hood to shield the ground glass from extraneous light, a focusing magnifier, a cable release, film holders, an exposure meter, and a carrying case.

During the evolution of the various types of cameras, 35-mm and roll-film cameras have borrowed some view camera features, such as perspective-control (PC) lenses that can be shifted off center to prevent convergence of vertical subject lines, as when photographing a tall building. View cameras also have borrowed features from small-format cameras, such as roll-film adapters, to make the view camera more user-friendly. A number of view camera refinements will be mentioned throughout the book and a comprehensive list will be included in Chapter 11, but we will start with a basic, no-frills generic or Brand X view camera.

Figure 1-3

An exploded view of a generic monorail view camera.

It is safer to list the major features normally associated with the name view camera than to try to write a rigorous definition. Such features will be listed and considered briefly here, then discussed in a more thorough manner in following chapters. It will be obvious to most readers that view cameras have no monopoly on all of the following features that characterize them:

- Ground-glass viewing for composing and focusing.

- Lateral, vertical, and angular adjustment of the lens and back.

- Accommodation of interchangeable lenses.

- Flexible bellows connecting the front and back of the camera.

- Large film size, usually in sheet form.

- Designed to be used on a tripod.

Figure 1-4

Ground-glass viewing.

In this book we are concerned primarily with conventional view cameras, but attention will be given to cameras having some view camera features even though they are not normally classified as view cameras.

A quick look at the characteristic view camera features will help us understand why view cameras have earned a reputation for versatility and the ability to produce photographs of exceptional quality.

1.2 Ground-Glass Viewing

The ground glass on a view camera displays the image exactly as it will be recorded on the film (Figure 1-4).

This enables the photographer to compose the picture precisely to the edges of the usable area of the film, to focus precisely either with the unaided eye or with a focusing magnifier, to check parallelism of image lines, and to check the depth of field at the selected f-number.

These advantages of ground-glass viewing must be weighed against the disadvantages. To see a vivid image it is necessary to shield the ground glass from light from the rear of the camera. This is usually done by placing a focusing cloth over the back of the camera and the photographer’s head or with a focusing hood attached to the back of the camera. Another disadvantage of ground-glass viewing is that the image is inverted. Most experienced view camera users have adapted to the inverted image, and some even claim that it assists them in evaluating the composition. Reflex viewing hoods are available for some view cameras for photographers who prefer to see a right-side-up, but laterally reversed, image.

1.3 Lateral, Vertical, and Angular Adjustments

By adjusting the relative positions of the lens and the film (Figure 1-5), view camera users can exercise the following controls over the image:

- The elimination of convergence or the exaggeration of convergence of parallel lines in the subject.

- The alteration of the plane of sharp focus either to render a subject entirely sharp or to intentionally create unsharpness in parts of the subject.

- The control of cropping—vertically, horizontally, and rotationally.

Figure 1-5

View camera adjustments.

The need for perspective, sharpness, and cropping controls by photographers who want to use roll film can be met by attaching a roll-film camera body or adapter to the back of a view camera. A lens that can be moved off center in different directions with respect to the film, providing some perspective and cropping control with a 35-mm camera, was introduced as the PC (perspective control) lens by Nikon in 1962.

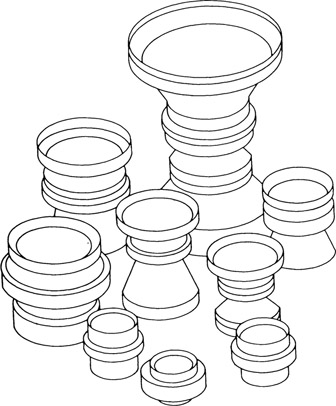

Figure 1-6

Interchangeable lenses.

1.4 Interchangeable Lenses

Since lenses need to be attached only to the proper lens board to be used on a view camera, almost any lens that has adequate covering power can be used (Figure 1-6). This feature provides the photographer with control over the size of the image and the area of the scene included on the film with the camera in a fixed position. It also enables the photographer to change the camera-to-subject distance while maintaining the same image size.

It is not always possible to place the camera at the preferred distance from the subject. Photographs made indoors often force the photographer to place the camera closer to the subject than desired, and outdoors the photographer is often forced to select a viewpoint farther from the subject than desired. Interchangeable lenses enable the photographer to adapt to both situations. Where the placement is not limited, the photographer may select the viewpoint on the basis of perspective or other considerations, and then select the lens that will produce the desired image size.

1.5 Flexible Bellows

Figure 1-7

Flexible bellows.

The flexible bellows on a view camera makes it possible to vary the distance between the lens and the film over a large range (Figure 1-7). This increases the usefulness of a camera in two important ways. First, it makes it possible to focus on objects at distances ranging from infinity down to very close to the camera. A large lens-to-film distance is necessary to obtain large images of small objects. A typical view camera is capable of producing an image that is one to two times the size of the object with normal focal length lenses. With shorter focal length lenses, even larger images can be obtained. Using a 2-in. focal length lens on a view camera with a 20-in. bellows extension, for example, will produce an image that is nine times as large as the object.

Typical 35-mm single-lens reflex cameras are able to focus from infinity down to a distance of approximately 1½ ft, producing a maximum image size that is approximately one-seventh the size of the object. Specially designed macro lenses for 35-mm cameras are capable of producing somewhat larger images, typically up to life size, or a 1:1 scale of reproduction, without the addition of extension tubes or a bellows.

A second function of the flexible bellows is to enable the photographer to use a wide range of focal length lenses. When photographing objects at moderate to long distances, the lens-to-film distances must be approximately equal to the focal lengths, and the image sizes will be approximately proportional to the focal lengths. Therefore, to include a wide angle of a scene it is necessary to use a short focal length lens and a short lens-to-film distance, whereas to obtain a large image of a distant object it is necessary to use a long focal length lens and a large lens-to-film distance. Some modular-type view cameras are designed so that extensions can be added to the bellows and the bed, making it possible to obtain very large lens-to-film distances.

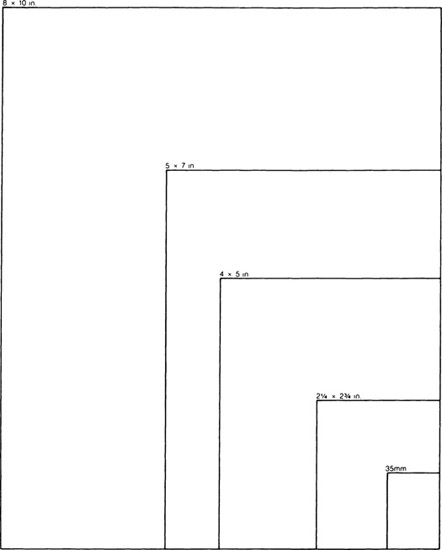

1.6 Large Film Size

In situations where image quality is the most important consideration, large film sizes are preferred (Figure 1-8). Photographers concerned with obtaining the best possible quality use film large enough to permit them to make contact prints rather than projection prints, thereby avoiding the inevitable loss of definition resulting from the addition of another optical system between the subject and the final print image. It is also easier for photographers to check image composition, including possible convergence of parallel subject lines, on the ground glass of a view camera than in a viewfinder (Figure 1-9).

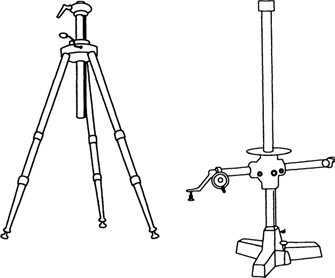

1.7 Camera Support

Because view cameras are designed to be used on tripods and studio stands, there is a greatly reduced risk of loss of image definition due to camera movement than with handheld cameras (Figure 1-10). Using a camera on a tripod also encourages the photographer to exercise greater care and give more attention to every aspect of making.the photograph. In picture-making situations involving live models, using the camera on a tripod enables the photographer to come out from behind the camera to interact with the subjects.

Figure 1-8

Film size comparison.

Figure 1-9

The ground glass on a large-format view camera facilitates arranging objects to conform to an art director’s layout. (Original ill color.)—Len Rosenberg

1.8 Advantages and Limitations of View Cameras

No single type of camera is suitable for use in all types of picture-making situations, and professional photographers who do a variety of types of photography typically own two or more different types of cameras. The most obvious limitations of view cameras with respect to photographing action scenes are that the camera must be used on a tripod and there is an inherent delay between the time the image isf composed and focused on the ground glass and when the film can be exposed—although some view cameras have features that considerably shorten the delay. View cameras are widely used, however, for making photographs that include people, including portraits made either in a studio or on location and advertising photographs that include models, in addition to the many types of photography where the field of view remains constant and it is not necessary for the camera to follow any internal movement.

Figure 1.10

As alternative supports for view cameras, tripods offer the advantage of portability and lower cost, while studio stands offer greater stability and maximum height.

Sheet film is more expensive than 35-mm film and roll film, especially in the larger-format sizes, and is not as convenient to have processed as taking 35-mm color film to a photofinisher. View cameras tend to be bulky and require the use of a tripod, which is an inconvenience when traveling, although some view cameras and tripods are sufficiently compact and light enough to carry in a backpack.

Among the advantages view cameras have over small-format cameras are the superior image quality produced with the larger sizes of film, the precision with which images can be composed and focused on the large ground glass, and especially the image control provided by the swings, tilts, and other view camera adjustments, combined with an unlimited choice of lenses. Also, with modular-type view cameras, the camera can often be modified to meet a wide variety of picture-making needs, including the use of roll film.

Notes

1 Eaton S. Lothrop, Jr., A Century of Cameras. Rochester, NY: International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1973, p. 1.

2 L. Stroebel and R. Zakia, eds., The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography, 3rd ed. Boston: Focal Press, 1993, p. 10.

3 L. Stroebel, View Camera Technique, 1st ed. Boston: Focal Press, 1967, p. 240; L. Stroebel, View Camera Technique, 6th ed. Boston: Focal Press, 1993, pp. 246-247.