1

Broadcast Station Management

This chapter examines broadcast station management by

• defining management and tracing the roots of today’s management thought and practice

• identifying the functions and roles of the broadcast station general manager and the skills necessary to carry them out

• discussing the major influences on the general manager’s decisions and actions

As the year 2000 approached, many Americans were preoccupied with the projected havoc that the so-called “millennium bug” would inflict. They were flooded with predictions that the computer, the revolutionary technology that controls the nation’s transportation, utilities, banking, and many other institutions, would plunge society into chaos. And all because programmers had failed to anticipate the consequences—when a new century began—of identifying years only by their last two digits. In the event, of course, the new millennium began as the old one had ended, with only isolated problems.

That the dire predictions proved to be unfounded may be attributed to the fact that decision makers throughout the country acted. They digested the facts, contemplated the alternatives, formulated plans, and implemented them. In other words, they managed change.

Managing change is a way of life for broadcast station managers, who have to contend routinely with a shifting public policy climate and accelerating technological innovation. But that is only one of the challenges they confront. Like any other business, the station must be operated profitably if it is to survive and satisfy the financial expectations of its owners. At the same time, it must respond to the interests of the community it is licensed to serve by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Balancing the private interests of owners and the public interest of listeners or viewers is a continuing challenge.

A broadcast station engages in many functions. It is an advertising medium, an entertainment medium, an information medium, and a service medium. To discharge those functions in a way that satisfies advertisers, audiences, and employees is an additional challenge. Another challenge grows out of the increasingly competitive environment in which broadcast stations operate.

Internet and satellite radio are alternatives to radio stations, whose average weekly listenership is down two hours from the late 1990s.

Television station managers face continuing competition from wired cable, which added more than five million subscribers between 2000 and 2005.1 In the same period, direct broadcast satellite (DBS) services more than doubled their penetration of TV households to 19 percent.2 Add to the mix digital video recorders (DVRs), videocassette recorders (VCRs), digital video disk (DVD) players, the Internet, and other content-reception devices, and it is easy to understand why managers conclude that they face unprecedented competition.

Responsibility for a station’s operation is entrusted by the owners to a chief executive, usually called the general manager. As a result of the explosion in in-market consolidation of radio stations in the 1990s, many general managers found themselves running multiple stations or “clusters.” Typically, they are called market managers. This chapter will look at the functions and roles of the person charged with ultimate responsibility for the fate of a broadcast operation, be it a stand-alone or part of a cluster.

First, however, it will be helpful to consider what management is, as well as the evolution of management thought and practice during the lifetime of broadcasting.

MANAGEMENT DEFINED

If you were to ask a group of people what management means, chances are that each would offer a different definition. That is not surprising, given the diversity and complexity of a manager’s responsibilities.

Schoderbek, Cosier, and Aplin define it as “a process of achieving organizational goals through others.”3 Resource acquisition and coordination are emphasized by Pringle, Jennings, and Longenecker: “Management is the process of acquiring and combining human, financial, informational, and physical resources to attain the organization’s primary goal of producing a product or service desired by some segment of society.”4 Others view it from the perspective of the functions that managers perform. For example, Carlisle speaks of “directing, coordinating, and influencing the operation of an organization so as to obtain desired results and enhance total performance.”5

Mondy, Holmes, and Flippo expand those functions and underline the importance of people, as well as materials: “Management may be defined as the process of planning, organizing, influencing, and controlling to accomplish organizational goals through the coordinated use of human and material resources.”6 That is the definition that will be used in this book.

EVOLUTION OF MANAGEMENT THOUGHT

It is tempting to think of management as a comparatively modern practice, necessitated by the emergence of large business organizations. However, as early as 6000 B.C., groups of people were organized to engage in undertakings of giant proportions. The Egyptians built huge pyramids. The Hebrews carried out an exodus from Egyptian bondage. The Romans constructed roads and aqueducts, and the Chinese built a 1500-mile wall. It is difficult to believe that any of these tasks could have been accomplished without the application of many of today’s management techniques.

To understand current management concepts and practices requires familiarity with the evolution of management thought. It traces its start to the dawn of the twentieth century, when the foundations of what later would be called broadcasting were being laid. Just as broadcasting has evolved, so has systematic analysis of management. The dominant traits of different managerial approaches have been identified and grouped into so-called schools. The first was the classical school of management.

THE CLASSICAL SCHOOL

Classical management thought embraces three separate but related approaches to management: (1) scientific management, (2) administrative management, and (3) bureaucratic management.

Scientific Management

At its origin, scientific management focused on increasing employee productivity and rested on four basic principles:

• systematic analysis of each job to find the most effective and efficient way of performing it (the “one best way”)

• use of scientific methods to select employees best suited to do a particular job

• appropriate employee education, training, and development

• responsibility apportioned almost equally between managers and workers, with decision-making duties falling on the managers

The person associated most closely with this school is Frederick W. Taylor (1856–1915), a mechanical engineer, who questioned the traditional, rule-of-thumb approach to managing work and who earned the title “father of scientific management.”

Taylor believed that economic incentives were the best motivators. Workers would cooperate if higher wages accompanied higher productivity, and management would be assured of higher productivity in return for paying higher wages. Not surprisingly, he was criticized for viewing people as machines.

However, his contributions were significant. Management scholar Peter Drucker attributes to Taylor “the tremendous surge of affluence … which has lifted the working masses in the developed countries well above any level recorded before.”7 Job analysis, methods of employee selection, and their training and development are examples of ways in which principles of scientific management are practiced today.

Administrative Management

If Taylor was the father of scientific thought, the French mining and steel executive Henri Fayol (1841–1925) can lay claim to being the father of management thought. While Taylor looked at workers and ways of improving their productivity, Fayol considered the total organization with a view to making it more effective and efficient. In so doing, he developed a comprehensive theory of management and demonstrated its universal nature.

His major contributions to administrative theory came in a book, General and Industrial Management, in which he became the first person to set forth the functions of management or, as he called them, “managerial activities”:

• Planning: Contemplating the future and drawing up a plan to deal with it, which includes actions to be taken, methods to be used, stages to go through, and the results envisaged.

• Organizing: Acquiring and structuring the human and material resources necessary for the functioning of the organization.

• Commanding: Setting each unit of the organization into motion so that it can make its contribution toward the accomplishment of the plan.

• Coordinating: Unifying and harmonizing all activities to permit the organization to operate and succeed.

• Controlling: Monitoring the execution of the plan and taking actions to correct errors or weaknesses and to prevent their recurrence.8

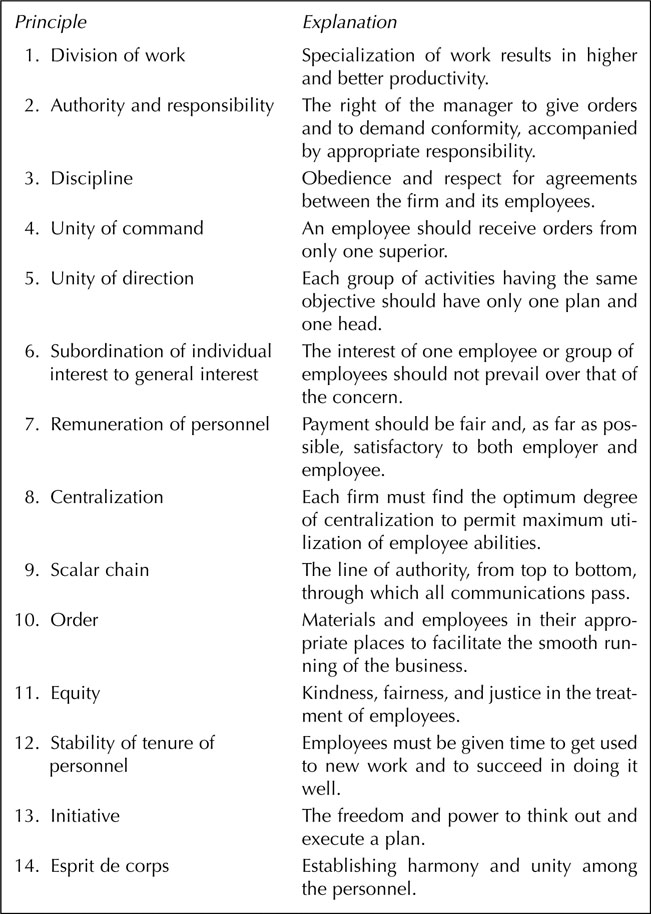

To assist managers in carrying out these functions, Fayol developed a list of 14 principles (Figure 1.1). He did not suggest that the list was exhaustive, merely that the principles were those that he had needed to apply most frequently. He warned that such guidelines had to be flexible and adaptable to changing circumstances.

Figure 1.1 Fayol’s 14 principles of management.

(Source: Henri Fayol, General and Industrial Management. Translated by Constance Storrs. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons, 1965, pp. 19–42. The explanations have been paraphrased.)

Fayol’s contributions may appear to be merely common sense in today’s business environment. However, the functions of planning, organizing, and controlling that he identified are still considered fundamental to management success. Many of his principles are incorporated in business organization charts and, in the case of equity, are enshrined in law.

Bureaucratic Management

At the same time that Taylor and Fayol were developing their thoughts, Max Weber (1864–1920), a German sociologist, was contemplating the kind of structure that would enable an organization to perform at the highest efficiency. He called the result a bureaucracy and listed several elements for its success. They included:

• division of labor

• a clearly defined hierarchy of authority

• selection of members on the basis of their technical qualifications

• promotion based on seniority or achievement

• strict and systematic discipline and control

• separation of ownership and management9

It is unfortunate that contemporary society associates the word bureaucracy with incompetence and inefficiency. While it is true that a bureaucracy can become mired in rigid rules and procedures, Weber’s ideas have proved useful to many large companies that need a rational organizational system to function effectively, and they have earned him a berth in the annals of management thought as “the father of organizational theory.”

Contributors to the classical school of management concerned themselves with efforts to make employees and organizations more productive. Their work revealed several of their assumptions about the nature of human beings, among them the notion that workers are motivated chiefly by money and require a clear delineation of their job responsibilities and close supervision if work is to be accomplished satisfactorily. Such assumptions would not withstand the scrutiny of the school that followed.

THE BEHAVIORAL SCHOOL

The trend away from classical assumptions began with the human relations movement, which dominated during radio’s heyday in the 1930s and 1940s. Among the greatest contributors to the movement were Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933) and Chester I. Barnard (1886–1961), both of whom rejected the view of the “economic man” held by the classical theorists.

Follett, a philosopher, argued in her writings that workers can reach their full potential only as members of a group, which she characterized as the foundation of an organization. In reality, managers and workers are members of the same group and, thus, share a common interest in the success of the enterprise.

Barnard, the president of New Jersey Bell Telephone Company, conceived of an organization as a “system of consciously coordinated activities or forces of two or more persons.” As employees work toward the accomplishment of the organization’s objectives, they have to be able to satisfy their own needs. Identifying ways of meeting those needs and, simultaneously, enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of the organization, are the principal challenges facing managers.

However, the most far-reaching contributions to the human relations movement were made by Elton Mayo (1880–1949), a Harvard University psychologist. Between 1927 and 1932, Mayo and Fritz J. Roethlisberger (1898–1974) led a Harvard research team at Western Electric’s Hawthorne plant in Illinois. The research focused on ways of improving worker efficiency by evaluating the factors that influence productivity. Its results redirected the course of management thought and practice.

What was observed in only one of the experiments gives a clue to the importance of the Hawthorne studies. To determine the effect on productivity of lighting levels, illumination remained constant among one group of workers (control group) and was systematically increased and decreased among another (experimental group). Contrary to expectations, productivity in both groups rose, even when the lighting in the experimental group was decreased.

The result of this and other experiments, combined with observation and interviews, convinced Mayo and his team that factors other than the purely physical have an effect on productivity. They realized that the one constant factor was the degree of attention paid to workers in the experimental groups. Thus was born the Hawthorne Effect, which states that when managers pay special attention to employees, productivity is likely to increase, despite a deterioration in working conditions.

The recognition that social as well as physical influences play a role in worker productivity marked an important milestone. Henceforth, greater attention would have to be paid to the needs of employees, who were now perceived as something other than mechanical, interchangeable parts in the organization.

The human relations movement evolved into the behavioral management school. It assumed dominance in the 1950s and 1960s, as the new medium of television was establishing its popularity in American households. Among this school’s major contributions were new insights into the needs of individuals and their role in motivating workers.

In an attempt to formulate a positive theory of motivation, Abraham Maslow (1908–1970), a psychologist, asserted that human beings have certain basic needs and that each serves as a motivator. He identified five such needs and organized them in a hierarchy, starting with the most basic:

• Physiological: Food, water, sex, and other physiological satisfiers

• Safety: Protection from threat, danger, and illness; a safe, orderly, predictable, organized world

• Love: Affection and belongingness

• Esteem: Self-esteem and the esteem of others

• Self-actualization: Self-fulfillment; to become everything one is capable of becoming10

The physiological and safety needs are seen as primary needs, and the remainder, dealing with the psychological aspects of existence, as secondary. Maslow theorized that when one need is fairly well satisfied, it no longer serves as a motivator. Instead, attention turns to the next level on the hierarchy. However, he recognized that the order is not rigid, especially at the higher levels. For example, some people may value self-esteem more than love, and others may never aspire to self-actualization.

There is little empirical data available to support Maslow’s theory.11 Nonetheless, it led to the realization that satisfied needs might have little value in motivating employees and that different techniques might have to be used to motivate different people, according to their particular needs.

While Maslow considered all needs to be motivators, Frederick Herzberg (1923–2000), another psychologist, proposed that employee attitudes and behaviors are influenced by two different sets of considerations. He called them hygiene factors and motivators.12

Hygiene factors13 are those associated with conditions that surround the performing of the job and include the following: supervision; interpersonal relations with superiors, peers, and subordinates; physical working conditions; salary; company policies and administrative practices; benefits; and job security.

Responding to employees’ hygiene needs, concluded Herzberg, will eliminate dissatisfaction and poor job performance but will not lead to positive attitudes and more productive behaviors. Those are accomplished by meeting the second set of considerations, the motivators, or factors associated with the job content. They include achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, and advancement.

Interestingly, there is a close relationship between Herzberg’s hygiene factors and the lower-level needs identified by Maslow, and between the motivators and Maslow’s self-esteem and self-actualization needs.

The implications of this two-factor theory of motivation are clear. Employees have certain expectations about elements in the environment in which they work. When they are satisfactory, workers are reassured that things are as they ought to be, even though those feelings may not encourage them to greater productivity. However, when environmental expectations are not met, dissatisfaction ensues. An employer must provide for both the hygiene needs and the motivators to achieve a motivated work force. The critical task, therefore, lies in satisfying employees’ needs for self-actualization by giving them more responsibility, providing opportunities for advancement, and recognizing their achievement.

Studies appear to show that Herzberg’s theory is applicable more to professional and managerial-level employees than to manual workers. Nonetheless, his contributions provided a better understanding of motivation and have had significant effects on job design.

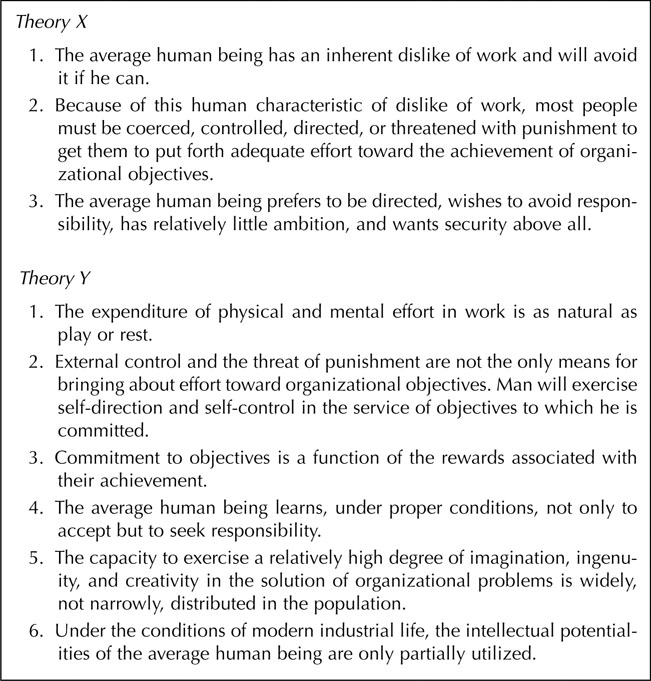

Influenced by the theorists of self-actualization, and especially Maslow, Douglas McGregor (1906–1964), an industrial psychologist, underscored the importance of assumptions about human nature and their effects on motivational methods used by managers. He argued that, despite important advances in the management of human resources, most managers clung to traditional assumptions, which he labeled Theory X (Figure 1.2). Managers who saw their employees as having a dislike of work, lacking ambition, and requiring direction were likely to rely on coercion, control, and even threats as motivational tools.

Figure 1.2 Theory X and Theory Y.

(Source: Douglas McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960, pp. 33–34, 47–48. Reprinted with permission of McGraw-Hill, Inc.)

McGregor offered Theory Y (Figure 1.2), which took an entirely different view of human nature. Managers who adopted these assumptions considered employees capable of seeking and accepting responsibility, and of exercising self-direction in furtherance of organizational goals—without control and the threat of punishment.

McGregor summarized the difference between the two theories in this way:

The central principle of organization which derives from Theory X is that of direction and control through the exercise of authority—what has been called the “scalar principle.” The central principle which derives from Theory Y is that of integration: the creation of conditions such that the members of the organization can achieve their own goals best by directing their efforts toward the success of the enterprise.14

By drawing attention to the key role played by employees in the attainment of organizational goals, and the importance of recognizing and striving to satisfy their needs, the behavioral school has had a lasting impact on management. In particular, it has resulted in greater attention to the work environment and on-the-job training for employees, and in a realization that people-management skills are a fundamental management attribute.

Management Science

This school of management thought had its origins during World War II and was known, in the beginning, as operations research. In some respects, it represented a reemergence of the quantitative approach favored by Taylor. However, advances in management technology, especially the computer, rendered it much more sophisticated.

Basically, management science involves construction of a mathematical model to simulate a situation. All variables bearing on the situation and their relationships are noted. By changing the values of the variables, the outcomes of different decisions can be projected.

By replacing descriptive analyses with quantitative data, this approach has been useful in management decision-making on matters that can be quantified, such as financial planning. A major shortcoming is its inability to predict the behavior of an organization’s human resources.

Modern Management Thought

By the 1960s, management theory incorporated elements of the classical, behavioral, and management science schools. However, theorists could not agree on a single body of knowledge that constituted the field of management. Indeed, one writer likened the situation to a jungle.15

Since then, steps have been taken toward clearing the jungle with the adoption of approaches aimed at integrating some of the divergent views of disciples of the earlier schools. Three of those approaches are systems theory, contingency theory, and total quality management.

Systems Theory

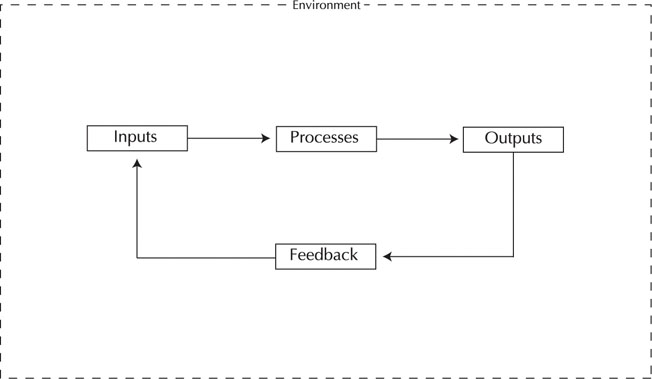

According to the systems theory, an enterprise is seen as a system, “a set of objects with a given set of relationships between the objects and their attributes, connected or related to each other and to their environment in such a way as to form a whole or entirety.”16

An organizational system is composed of people, money, materials, equipment, and data, all of which are combined in the accomplishment of some purpose. The subsystems typically are identified as divisions or departments whose activities aid the larger system in reaching its goals.

Certain elements are common to all organizational systems (Figure 1.3). They are inputs (e.g., labor, equipment, and capital) and processes, that is, methods whereby inputs are converted into outputs (e.g., goods and services). Feedback is information about the outputs or processes and serves as an input to help determine whether changes are necessary to attain the goals. Management’s role is to coordinate the input, process, and output factors and to analyze and respond to feedback.

Figure 1.3 Systems approach to organizational management.

The systems approach emphasizes the relationship between the organization and its external environment. Environmental factors are outside the organization and beyond its control. But they have an impact on its operations. Accordingly, management must monitor environmental trends and events and make changes deemed necessary to ensure the organization’s success.

Contingency Theory

The contingency, or situational, approach to management traces its current origins to systems theory and the desire to identify universal principles of management. It recognizes that principles advanced by earlier schools may be applicable in some situations, but not in others, and seeks an understanding of those circumstances in which certain managerial actions will bring about the desired results.

It is ironic that this line of thought did not emerge as a major force until the mid-1960s, since its significance in the study of leadership was recognized in the 1920s by Follett. She noted that “there are different types of leadership” and that “different situations require different kinds of knowledge, and the man possessing the knowledge demanded by a certain situation tends in the best managed businesses, other things being equal, to become the leader of the moment.”17

The recent study of contingency principles has been relatively sparse, focusing mostly on organizational structure and decision making. Finally, however, this approach has attracted the attention of theorists to functions other than leadership and has impressed on the field the realization that management is much more complex than earlier theorists imagined.

It is this complexity that makes it impossible to suggest a style for all managers, including those who manage broadcast stations. What is appropriate for one manager in one circumstance with one group of employees may be quite inappropriate for another manager in another circumstance with a different group.

Total Quality Management (TQM)

Revolutionary developments in the world and in the workplace triggered changes in management thought and practice in the last decade or so of the twentieth century. The end of communism’s dominance in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe created new opportunities in a world already characterized by the growing internationalization of business. An era of global interdependence was ushered in by the formation of a single trading bloc among European countries and by ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Technical innovation and the growing heterogeneity of the American workforce rendered the organizational world of the 1990s strikingly different from that in which early theorists operated.

Accompanying these developments was a focus on customers’ needs and, especially, on their expectations of quality in the products they purchase and the services they use. This gave rise to a new approach to management—total quality management. The approach may have been new in the United States, but its underpinnings were not. In fact, it drew elements from management science, scientific management, and the behavioral approach, and it may be characterized as another attempt to clear the jungle. Nor was its practice new. It was introduced in Japan in the aftermath of World War II by several Americans, the most prominent of whom was W. Edwards Deming (1900–1993), a statistician.

The foundation of Deming’s approach to TQM is the conviction that uniform product quality can be ensured through statistical analysis and control of variables in the production process. As the philosophy evolved and technological change became commonplace, his insistence that employees be trained to understand statistical methods and their application and to master new skills assumed greater significance. So, too, did awareness that employees are an integral part of the quality revolution and that, without their total commitment to continuous product or service improvement, any attempt to practice this management philosophy will be doomed.

Management Thought in the Twenty-first Century

Recognition of the importance of individuals and their commitment to organizational improvement are fundamental characteristics of the latest approach to management. It is called the learning organization.

Management thinking and practices described so far reflect responses to the challenges of the times. Proponents of the new approach have concluded that new challenges—including the accelerating pace of technological change, increased consumer choice and sophistication, and globalization—demand a new perspective.

The learning organization had its origins with the 1990 publication of Peter Senge’s book The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization. In the intervening years, Senge, his colleagues at MIT, and others have developed the concept and witnessed its adoption in organizations of different types and sizes.

In contrast to the traditional focus on organizational efficiency, the principal distinguishing feature of the learning organization is systematic problem solving. But that is not a job for managers and supervisors alone. Indeed, all members of the organization are expected to challenge the way business is done and to question the thought processes typically used to solve problems. Together, they work to identify new problems, develop solutions to them, and apply the solutions. That requires the free flow of information throughout the organization. It requires, also, that all organization members understand their job and how it relates to the jobs of others, share a vision of the organization’s purpose, and display a commitment to accomplish the purpose.

In large measure, the success of the learning organization hinges on management’s willingness to facilitate the exchange of information and to establish an environment conducive to continuous learning. Encouraging employees to use their creativity and providing them with the freedom and resources to engage fully in problem solving are additional requirements.

The contributions to management thought and practice described in this chapter provide some guidelines for the manager. However, pending the development of a set of universal management principles, the style of most managers probably is summarized best by business mogul T. Boone Pickens, Jr.: “A management style is an amalgamation of the best of other people you have known and respected, and eventually you develop your own style.”18

MANAGEMENT LEVELS

It is often assumed that management is concentrated at the top of an organization. In reality, anyone who directs the efforts of others in the attainment of goals is a manager. In most companies, including broadcast stations, managers are found at three levels:

• Lower: Managers at this level closely supervise the routine work of employees under their charge and are accountable to the next level of management. A radio station local sales manager who reports to the general sales manager is an example. So is a television control room supervisor who answers to the production manager.

• Middle: Managers who are responsible for carrying out particular activities in furtherance of the overall goals of the company are in this category. In broadcast stations, the heads of the sales, program, news, promotion and marketing, production, engineering, and business departments are middle managers.

• Top: Managers who coordinate the company’s activities and provide the overall direction for the accomplishment of its goals operate at this level. The general manager of a broadcast station is a top manager.

Even though the contents of the remainder of this chapter apply in varying degrees to all three levels, the focus will be on the top level, that occupied by the general manager.

MANAGEMENT FUNCTIONS

The general manager (GM) is responsible to the station’s owners for coordinating human and physical resources in such a way that the station’s objectives are accomplished. Accordingly, the GM is concerned with, and accountable for, every aspect of the station and its operation. In discharging the management responsibility, the GM carries out four basic functions: planning, organizing, influencing or directing, and controlling.

Planning

Planning involves the determination of the station’s objectives and the plans or strategies by which those objectives are to be accomplished. Through the planning process, many objectives may be identified. Usually, they can be placed in one of the following categories:

• Economic: Objectives related to the financial position of the station and focusing on revenues, expenses, and profits.

• Service: Programming that will appeal to audiences and be responsive to their interests and needs; the contribution of the station to the life of the community.

• Personal: Objectives of individuals employed by the station.

A major purpose of objective-setting is to permit the coordination of departmental and individual activity with the station’s objectives. Once the station’s objectives have been formulated, those of the different departments and employees within those departments can be developed. Individual objectives must contribute to the accomplishment of departmental objectives. In turn, they must be compatible with those of other departments and of the station. In addition, all objectives must be attainable, measurable, set against dead-lines, and controllable.

Once agreement on objectives has been reached, plans or strategies are developed to meet them. Planning provides directions for the future. However, it does not require the abandonment of plans that contribute to the achievement of the station’s current objectives and that are likely to be instrumental in enabling the station to accomplish its future objectives.

Planning cannot anticipate or control events. However, it has many benefits since it

• compels the GM to think about and prepare for the future

• provides a framework for decision making

• permits an orderly approach to problem solving

• encourages team effort

• provides a climate for individual career development and job satisfaction

Organizing

Organizing is the process whereby human and physical resources are arranged in a formal structure and responsibilities are assigned to specific units, positions, and personnel. It permits the concentration and coordination of activities and management control of efforts to attain the station’s objectives.

In the typical broadcast station, organizing involves the division of work into specialties and the grouping of employees with specialized responsibilities into departments. The following departments are found most frequently in commercial broadcast stations.

Sales Department

The sale of time to advertisers is the principal source of revenue for commercial radio and television stations and is the responsibility of a sales department, headed by a sales manager. Many stations subdivide the department into national sales and local/regional sales. Sales to national advertisers are entrusted to the national sales manager and the station’s sales representative company, or station rep. Local and regional sales are the responsibility of the station’s salespersons, typically called account executives.

Program Department

Under the direction of a program manager or director, the program department plans, selects, schedules, and monitors programs. The department also provides relevant content for the station’s Web site.

Promotion and Marketing Department

This function involves both program and sales promotion. The former seeks to attract and maintain audiences, while the latter is aimed at attracting advertisers. Both functions may be the responsibility of a promotion and marketing department. Some stations assign program promotion to the program department and sales promotion to the sales department.

News Department

In many stations, the information function is kept separate from the entertainment function and is supervised by a news director. The department is responsible for regularly scheduled newscasts, news and sports specials, documentary and public affairs programs, and for Web site news content.

Production Department

In radio, this department is headed by a production director or creative director and is charged with writing and producing commercials. Commercial production is a responsibility of its television counterpart. In many TV stations, the department also includes technical support personnel for newscast production and for master control operations. A production manager supervises the department’s activities.

Engineering Department

A chief engineer or technical manager heads this department. It selects, operates, and maintains studio, control room, and transmitting equipment, and often oversees the station’s computers. Engineering staff are also responsible for technical monitoring in accordance with the requirements of the FCC. In some stations, studio production personnel are located in the department.

Business Department

The business department carries out a variety of tasks necessary to the functioning of the station as a business. They include secretarial, billing, bookkeeping, payroll and, in many stations, personnel responsibilities.

Broadcast stations engage in other functions, which may be assigned to separate departments or subdepartments, or may be included in the duties of departments already identified. The following additional functions are among the most common:

Traffic often is carried out by a subdepartment of the sales department. It is called the traffic department and is headed by a traffic manager. The function includes the daily scheduling on a program log of all content to be aired by the station, the compilation of an availabilities sheet showing times available for purchase by advertisers, and the monitoring of all advertising content to ensure compliance with commercial contracts.

Continuity is concerned chiefly with the writing of commercial copy and, in many stations, constitutes a subdepartment within the sales department. The continuity director supervises its work and reports to the sales manager. In stations where the writing of program material and public service announcements is included, the continuity director may answer to the heads of both the sales and program departments.

The general manager’s success in organizing rests heavily on the selection of employees. Of particular importance is the selection of department heads, to whom the GM delegates responsibility for the conduct and accomplishments of the various departments.

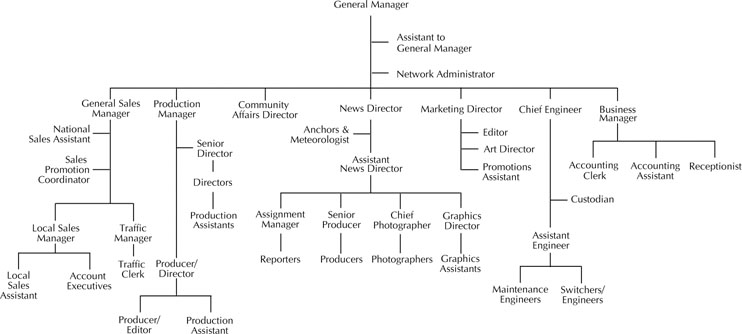

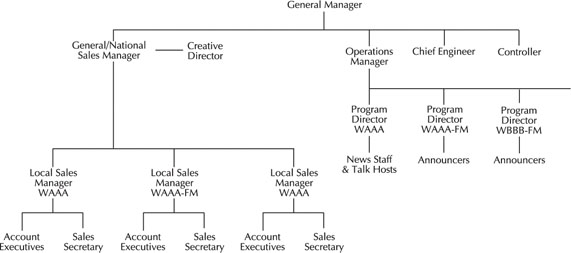

The GM also must strive to ensure that the organizational structure enables the station to meet its objectives, and that problems arising from overlapping or nonexistent responsibility are corrected. The structure is influenced by many factors. They include the number of employees, the size of the market, and the preferences of the GM. As a result, there is no “typical” organization. Figure 1.4 contains an example of the structure of a mediummarket television station. Figure 1.5 reflects the organization of three commonly owned radio stations in a market of similar size.

Figure 1.4 Organization of a commercial television station in a medium market.

Figure 1.5 Organization of three radio stations operating under the same owner and general manager.

Influencing or Directing

The influencing or directing function centers on the stimulation of employees to carry out their responsibilities with enthusiasm and effectiveness. It involves motivation, communication, training, and personal influence.

Motivation

The major theories of motivation were discussed earlier in this chapter. For the general manager, motivation is a practical issue, since the success of the station is tied closely to the degree to which employees are able to satisfy their needs. The greater their satisfaction, the more likely it is that they will contribute fully to the attainment of the station’s objectives. Accordingly, the GM must be aware of the needs of individual employees and must create an environment in which they want to be productive.

Basic needs include adequate compensation and fringe benefit programs, safe and healthy working conditions, friendly colleagues, and competent and fair supervision. For most employees, such needs are met adequately and do not serve as powerful motivators.

Satisfaction of other needs may have a more significant impact on how employees feel about themselves and the station and on their efforts to contribute to the station’s success. Included in these higher-level needs are factors such as job title and responsibility, praise and recognition for accomplishments, opportunities for promotion, and the challenge of the job. Once basic needs are satisfied, therefore, the GM must respond to those higher-level needs if motivation is to be successful.

Communication

Communication is vital to the effective discharge of the management function. It is the means by which employees are made aware of the station’s objectives and plans and are encouraged to play a full and effective part in their attainment.

As a result, the general manager must communicate to employees information they need and want. They need information on what is expected of them. The job description sets forth general guidelines, but they must have specifics on their role in carrying out current plans. If they are to shoulder their duties willingly and effectively, they want to know about matters influencing their economic status and their authority to carry out responsibilities.

This downward flow of communication is important, but it must be accompanied by management’s willingness to listen to and understand employees. Accordingly, it is necessary to provide mechanisms for an upward flow of communication from employees to supervisors, department heads, and the GM. Departmental or staff meetings, suggestion boxes, and an opendoor policy by management permit such a flow.

Lateral flow, or communication among individuals on the same organizational level, also is important in coordinating the activities of the various departments in pursuit of the station’s plans and objectives. A method used by many stations to ensure such a flow is the establishment of a management team that meets on a regular basis. Usually, it comprises the general manager and all department heads.

Training

Most employees are selected because they possess the background and skills necessary to carry out specific responsibilities. However, they may have to be trained in the use of new equipment or the application of new procedures. Occasionally, employees are hired with little experience and have to be trained on the job. Whenever training is necessary, the general manager must make certain that it is provided and that it is supervised by competent personnel.

One of the major benefits of training programs is the provision of opportunities for existing employees to prepare themselves for advancement in the station. As a result, employee morale is heightened, and the station enjoys the advantage of creating its own pool of qualified personnel.

Some stations encourage employees to advance their knowledge and skills by paying for their participation in workshops, seminars, and college courses, as well as their attendance at meetings of state and national broadcasting associations. In all such cases, the general manager should be sure that the experiences will contribute to the employee’s ability to carry out responsibilities more effectively, thereby assisting the station in meeting its objectives.

Personal Influence

Stimulating employees to produce their best efforts requires that the general manager and others in managerial or supervisory positions command respect, loyalty, and cooperation. Among the factors that contribute to such a climate are management competence, fairness in dealings with employees, willingness to listen to and act on employee observations and complaints, honesty, integrity, and similar personal characteristics. In effect, personal influence includes all those behaviors and attitudes that contribute to employees’ perceptions of their importance in the station’s efforts and achievements and the worthiness of the enterprise of which they are a part.

Controlling

Through planning, the station establishes its objectives and plans for accomplishing them. The control process determines the degree to which objectives and plans are being realized by the station, departments, and employees.

Periodic evaluation of individuals and departments allows the general manager to compare actual performance to planned performance. If the two do not coincide, corrective action may be necessary.

To be effective, controlling must be based on measurable performance. The size and composition of the station’s audience can be measured through ratings. If the audience attracted to the station or to certain programs does not match projections, the control process permits the recognition of that fact and leads to discussions about possible solutions. The result may be a change in the plan, such as a revision downward of expectations, or actions to try to attain the original objectives.

Similarly, sales revenues can be measured. An analysis may reveal that projected revenues were unrealistic and that an adjustment is necessary. On the other hand, if the projections are realizable, discussions may lead to a decision to hire additional account executives, make changes in the rate card, or adjust commission levels.

The costs of operation are measurable too. They are discussed in Chapter 2, “Financial Management,” along with methods of controlling them.

MANAGEMENT ROLES

Management functions reflect the major responsibilities of the general manager. However, they provide little insight into the diverse and complex activities the general manager undertakes on a daily basis.

Henry Mintzberg found that managerial activity is characterized by brevity, variety, and fragmentation.19 Managers spend short periods of time attending to different tasks and are interrupted frequently before a specific task is accomplished. Writing memoranda, reading and writing letters, faxes, and email messages, receiving and making telephone calls, attending meetings, and visiting employees and persons outside the organization are examples of activities that consume a great deal of a manager’s time and energy. There are others as well.

Mintzberg identified ten roles and grouped them in three categories: (1) interpersonal, (2) informational, and (3) decisional.20

Interpersonal Roles

As the symbolic head of the organization, the manager serves as a

• Figurehead: The manager carries out duties of a legal or ceremonial nature. For the broadcast station general manager, this role is discharged through the signing of documents for submission to the FCC and by representing the station at community events, for instance.

• Leader: Establishing the workplace atmosphere and guiding and motivating employees are examples of ways in which the general manager carries out the leadership role.

• Liaison: The general manager is the liaison between the station’s owners and its employees. Dealings with peers and other individuals and groups outside the station link the organization with the environment. Accordingly, the GM’s relationships with other general managers, program suppliers, and community groups reflect this role.

Informational Roles

The manager is the organization’s “nerve center” and, as such, seeks and receives a large volume of internal and external information, both oral and written. In these roles, the manager acts as a

• Monitor: Information permits the manager to understand what is happening in the organization and its environment. Receipt of the latest sales report or threats of a demonstration to protest the planned airing of a program enable the GM to exercise this role.

• Disseminator: The manager distributes external information to members of the organization and internal information from one subordinate to another.

• Spokesperson: In this role, the manager speaks on behalf of the organization. An example would be a news conference at which the GM reveals plans for a new broadcast facility.

Decisional Roles

These roles grow out of the manager’s responsibility for the organization’s strategy-making process and involve the manager as

• Entrepreneur: The manager is the initiator and designer of controlled change. For example, the GM of a TV station may set in motion procedures aimed at attaining first place in local news ratings.

• Disturbance handler: In this role, managers deal with involuntary situations and change that is partially beyond their control. An example would be resolving a dispute between the program manager and the sales manager on the advisability of carrying a particular program.

• Resource allocator: The manager determines priorities for the expenditure of money and employee effort.

• Negotiator: The manager represents the organization in negotiating activity. Working out a contract with a program supplier or union would place the GM in this role.

MANAGEMENT SKILLS

To carry out their functions and roles effectively, managers require many skills. Robert L. Katz identifies three basic skills that every manager must have in varying degrees, according to the managerial level.21 For the general manager of a broadcast station, all are important:

• Technical: Knowledge, analytical ability, and facility in the use of the tools and techniques of a specific kind of activity. For the general manager, that activity is managing. While it does not demand the ability to perform all the tasks that characterize a broadcast station, it does require sufficient knowledge to ask pertinent questions and evaluate the worth of the responses. Accordingly, the GM should have knowledge of

• the objectives of the station’s owners

• management and the management functions of planning, organizing, influencing or directing, and controlling

• business practices, especially sales and marketing, budgeting, cost controls, and public relations

• the market, including the interests and needs of the audience and the business potential afforded by area retail and service establishments

• competing media, the sources and amounts of their revenues

• broadcasting and allied professions, including advertising agencies, station representative companies, and program and news services

• the station and the activities of its departments and personnel

• broadcast laws, rules, and regulations, and other applicable laws, rules, and regulations

• contracts, particularly those dealing with network affiliation, station representation, programming, talent, music licensing, and labor unions

• Human: The ability to work with people and to build a cooperative effort. The general manager should have the capacity to influence the behavior of employees toward the accomplishment of the station’s objectives by motivating them, creating job satisfaction, and encouraging loyalty and mutual respect. An appreciation of the differing skills and aspirations of employees and departments also is essential if the station’s activities are to be combined in a successful team effort.

• Conceptual: The ability to see the enterprise as a whole and the dependence of one part on the others. To coordinate successfully the station’s efforts, the GM must recognize the interdependence of programming and promotion, sales and programming, and production and engineering, for example. Equally important is the ability to comprehend the relationship of the station to the rest of the broadcast industry, to the community, and to prevailing economic, political, and social forces, all of which contribute to decisions on directions that the station will take and the subsequent formulation of objectives and policies.

To these skills, the successful general manager should add desirable personal qualities. They include:

• foresight, the ability to anticipate events and make appropriate preparations

• wisdom in choosing among alternative courses of action and courage in carrying out the selected action

• flexibility in adapting to change

• honesty and integrity in dealings with employees and persons outside the station

• responsiveness and responsibility to the station’s owners, employees, and advertisers

The GM also must be responsive and display responsibility to the community by leading the station in its community relations endeavors and by setting an example for other employees to follow.

INFLUENCES ON MANAGEMENT

The degree to which the general manager possesses and uses the skills described will play an important part in determining the station’s fortunes. But there are other forces that contribute to the GM’s decisions and actions and that influence the effectiveness with which the management responsibility is discharged. The most significant influences are described in this section.

The Licensee

Ultimate responsibility for the operation of a radio or television station rests with the licensee, the person or persons who have made a financial investment in the enterprise and enjoy an ownership interest. Like all investors, they expect that they will reap annual profits from the station’s operation and that the financial worth of their investment will increase in time. As a result, the general manager must seek to satisfy their expectations and weigh the financial impact of all actions.

The Competition

Radio and television stations compete against each other and against other media in the market for advertising dollars. That translates into competition for audiences. A station gains audience from, or loses audience to, other stations, and few significant management actions will pass without producing a reaction among competitors. Similarly, many of the general manager’s actions will be influenced by those of competing stations.

The Government

As detailed in Chapter 7, “Broadcast Regulations,” the federal government is a major force in broadcast station operation. It exerts its influence through its three branches—executive, legislative, and judicial—and through independent regulatory agencies, chiefly the Federal Communications Commission.

Executive Branch

Broadcast stations are affected by the actions of several executive branch departments, notably the Executive Office of the President, the Department of Justice, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA).

Executive Office of The President

The President influences broadcast policy and regulation in numerous ways. He can recommend legislation; he nominates members for, and appoints the chairperson of, regulatory agencies whose policies, rules, and regulations apply to radio and television stations; and he can exert influence through the annual federal budget process.

Department of Justice

This department prosecutes violators of the Communications Act and of rules and regulations applicable to broadcast station operation. The department’s antitrust division is concerned with station ownership and may take action when it believes that ownership or other circumstances are resulting in a restraint of trade.

Food and Drug Administration

A division of the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA regulates mislabeling and misbranding of advertised products.

National Telecommunications and Information Administration

Part of the Department of Commerce, the NTIA advises the President on telecommunications policy issues.

Legislative Branch

The House of Representatives and the Senate enact broadcast legislation and approve the budgets of the regulatory agencies. In addition, the Senate has the power of approval of presidential nominees for regulatory agencies. Both the Senate and the House may influence broadcast policy and regulation through congressional hearings on issues of controversy or concern.

Judicial Branch

Federal courts try cases against violators of laws, rules, and regulations, and hear appeals against decisions and orders handed down by regulatory agencies.

Regulatory Agencies

Federal regulatory agencies operate like a fourth branch of government and enjoy executive, legislative, and judicial powers. The agency with the greatest influence on broadcast operations is the FCC, whose role is described later. The commission regulates radio and television stations in accordance with the terms of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended. For the general manager, its most significant and awesome power is that of renewing or revoking the station’s license to operate.

Other regulatory agencies that influence the broadcast media are the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which polices unfair trade practices and false or deceptive advertising, and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), whose concerns include the placement and maintenance of broadcast towers.

Broadcasters are engaged in interstate commerce and, for the most part, are subject to federal authority. However, state and local governments may also have an impact on stations through laws on matters such as business incorporation, taxes, advertising practices, individual rights, and zoning and safety ordinances.

The Labor Force

The number of people available for work, and their skills, have a direct influence on the success of all businesses, including broadcasting. The station’s ability to hire and retain qualified and productive employees is a major determinant of the station’s performance.

Labor Unions

The general manager of a station in which personnel are represented by one or more unions is required to abide by the terms of a union contract governing, among other items, wages and fringe benefits, job jurisdiction, and working conditions (for details, refer to Chapter 3, “Human Resource Management”). In nonunionized stations, the general manager must be attentive to the treatment of employees, not only for reasons of morale or competitiveness, but to guard against the threat of unionization.

The Public

To generate advertising revenue, the station must attract an audience for its programming. Accordingly, as noted in Chapter 4, “Broadcast Programming,” the public is a major force in program decision making. Organized publics, also known as citizen or pressure groups, attempt to influence decisions on a wide range of actions. Among the causes undertaken by different groups have been improvement in employment opportunities for minorities, the elimination of violent and sexual content, and the promotion of programming for children.

Advertisers

The financial fate of commercial broadcast stations rests on their appeal to advertisers. Attracting audiences sought by advertisers and enabling advertisers to reach them at an acceptable cost are major factors in program and sales decisions.

Economic Activity

The state of the local and national economy determines the amount of money people have to spend on advertised products and their spending priorities. When the economy is sluggish, businesses pay more attention than usual to their advertising expenditures and may be tempted to reduce them, thereby posing a challenge for broadcast stations and other advertiser-supported media.

The Broadcast Industry

Standards of professional performance and content are set forth in a station’s policy book or employee handbook. Individual employees subscribe to industrywide standards formulated by broadcast organizations or associations in which they hold membership. The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) in 2004 announced plans for a task force on “responsible programming” that would consider adoption of an industry code of conduct.

Social Factors

Since broadcast stations must be responsive to the interests of their communities, social factors play an important role in program decisions. Stations must analyze, interpret, and respond to trends in the size and composition of the local population, employment practices, income, and spending habits.

Technology

Advances in technology resulted in the emergence of radio and television broadcasting and continue to play a major part in station practices. Today, the general manager experiences, and must respond to, the influence of new broadcast technologies, as well as those technologies that provide alternative means of accessing entertainment and information content.

WHAT’S AHEAD?

In an era of dramatic change and accompanying uncertainty, it appears that TV station general managers can prepare for one event with some certainty: the end of analog and the switch to all-digital broadcasting in 2009.

The prospect of Congressional legislation establishing that year as the “hard date” became real when NAB President Eddie Fritts told the Senate Commerce Committee in July 2005 that the organization would support such a law. Now, the planning can begin in earnest to capitalize on the opportunities that digital affords.

As they prepare for the all-digital age, general managers face many challenges. One of the most significant will be the decision on how to use the newly available channels. It will have to take into account factors such as the sources and availability of content, its appeal to targeted audiences, and the recruiting of suitably skilled employees. Probably the most important consideration will be the revenue-generation potential of the decision. Already, the industry has spent an estimated $3.5 billion on the digital build-out and additional expenditures lie ahead.

As noted in Chapter 4, “Broadcast Programming,” the general manager may find partnerships with telephone companies appealing. Even alliances with competing stations are a possibility. One group CEO has proposed that broadcasters pool their capital and their digital channels to offer wireless cable in markets across the country.22

Expanding and diversifying program distribution methods will be important keys to success in the future. Increasingly, viewers are growing accustomed to “on-demand” media. In other words, they want to control what they use and when they use it. One 2005 study found that heavy and medium on-demand consumers account for more than one-third of Americans.23 Their number will continue to grow and managers must strive to respond to their desires.

The challenges posed by changing technologies and lifestyles will confront radio station general managers, too. Internet radio, satellite radio, iPods, and other audio sources provide listeners with an array of attractive alternatives. Again, consumer control is a major determinant of their choices. For example, the study cited earlier found that the top two reasons for using Internet radio are the ability to listen to content not found elsewhere and to control/choose the music played.24 At the same time, radio managers may find comfort in another of the study’s conclusions: more than 80 percent of Americans say that they will listen to terrestrial radio in the future as much as they do now, despite advancements in technology.25 Time will tell!

SUMMARY

Management is defined as the process of planning, organizing, influencing, and controlling to accomplish organizational goals through the coordinated use of human and material resources.

The current practice of management has been influenced by several schools. The first was the classical school, which focused on the productivity of organizations and their employees. It was followed by the behavioral school, which drew attention to the importance of satisfied employees to successful operation. Management science was characterized by attempts to quantify the likely outcomes of different managerial decisions. Modern management thought strives to integrate the various perspectives of earlier schools by concentrating on systems theory, contingency theory, and total quality management. The newest practice is the learning organization, which emphasizes systematic problem solving through the participation of all organizational members.

The general manager of a broadcast station has four major functions: (1) planning, or the determination of the station’s objectives and the plans or strategies to accomplish them; (2) organizing personnel into a formal structure, usually departments, and assigning specialized duties to persons and units; (3) influencing or directing, that is, stimulating employees to carry out their responsibilities enthusiastically and effectively; (4) controlling, or developing criteria to measure the performance of individuals, departments, and the station and taking corrective action when necessary.

On a day-to-day basis, the GM carries out several roles—interpersonal, informational, and decisional. Technical, human, and conceptual skills are required, together with personal attributes.

Among the significant influences on the GM’s decisions and actions are the licensee, competing media, the government, the labor force, labor unions, the public, and advertisers. Economic activity, the broadcast industry, social factors, and technology also are influential.

Technological advancements, and the changing consumer expectations they permit, will present both opportunities and challenges. Managers’ ability to respond effectively to the demands of the new environment will be vital to success.

CASE STUDY

You are the GM of a talk radio station. You have just arrived home after eating out with your wife. It’s about 11:15 P.M.

The telephone rings and you answer. Your program director is on the line. He wants to know if you have seen the late-night TV newscast. You haven’t. He tells you that the popular host of your midday program has been arrested for DUI. The newscast included footage of the host being led to a police car in handcuffs.

Next morning, you call the program director and the local sales manager to your office. You want to hear their thoughts on an appropriate course of action.

You begin by quoting from the station’s policy book. It states that employees convicted on alcohol or drug charges may be terminated.

The program director argues that—even if convicted—the host should be given a second chance. He has increased the numbers for the time period and his “loose cannon” style generates lots of controversy and calls.

The sales manager concurs. She says that advertiser demand for the program is growing and clients are pleased with the results of their buys.

EXERCISES

1. What factors will you weigh in determining how to deal with the host?

2. Do the arguments of the program director and the local sales manager have merit? Explain.

3. If you decide to go along with their recommendation, will you allow the host to remain on the air or remove him pending further legal proceedings? Justify your response.

4. If you decide not to dismiss him, will you attach conditions to his continued employment? If so, describe them.

NOTES

1 http://www.tvb.org/rcentral/mediatrendstrack/tvbasics/04.

2 Ibid.

3 Peter P. Schoderbek, Richard A. Cosier, and John C. Aplin, Management, p. 8.

4 Charles D. Pringle, Daniel F. Jennings, and Justin G. Longenecker, Managing Organizations: Functions and Behaviors, p. 4.

5 Howard M. Carlisle, Management Essentials: Concepts for Productivity and Innovation, p. 10.

6 R. Wayne Mondy, Robert E. Holmes, and Edwin B. Flippo, Management: Concepts and Practices, p. 6.

7 Peter F. Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices, p. 181.

8 Henri Fayol, General and Industrial Management, pp. 43–107. Explanations of the functions have been paraphrased.

9 Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, pp. 329–334.

10 A. H. Maslow, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Psychological Review, 50:4 (July 1943), pp. 370–396.

11 For an example, see Geert H. Hofstede, “The Colors of Collars,” Columbia Journal of World Business (September–October 1972), pp. 72–80. After studying job-related goals of more than 18,000 employees of one company with offices in 16 countries, Hofstede concluded that there was a high correlation with Maslow’s theory. The goals of professionals related to the higher needs, of clerks to the middle-range needs, and of unskilled workers to the primary needs.

12 Frederick Herzberg, Bernard Mausner, and Barbara Bloch Snyderman, The Motivation to Work, pp. 113–119.

13 Herzberg, Mausner, and Snyderman, op. cit., p. 113. Herzberg explained his use of the term hygiene as follows: “Hygiene operates to remove health hazards from the environment of man. It is not a curative; it is, rather, a preventive… Similarly, when there are deleterious factors in the context of the job, they serve to bring about poor job attitudes. Improvement in these factors of hygiene will serve to remove the impediments to positive job attitudes.”

14 Douglas McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise, p. 49.

15 Harold Koontz, “The Management Theory Jungle,” Academy of Management Journal, 4:3 (December 1961), pp. 174–186.

16 Peter P. Schoderbek, Charles D. Schoderbek, and Asterios G. Kefalas, Management Systems: Conceptual Considerations, p. 260.

17 Henry C. Metcalf and L. Urwick (eds.), Dynamic Administration: The Collected Papers of Mary Parker Follett, p. 277.

18 T. Boone Pickens, Jr., “Pickens on Leadership,” Hyatt Magazine, Fall/Winter 1988, p. 21.

19 Henry Mintzberg, The Nature of Managerial Work, pp. 31–35.

20 Mintzberg, op. cit., pp. 54–94.

21 Robert L. Katz, “Skills of an Effective Administrator,” Harvard Business Review, 52:5 (September–October 1974), pp. 90–102.

22 Harry A. Jessell, “Marshaling the Troops,” Broadcasting & Cable, April 26, 2004, p. 9.

23 Internet and Multimedia 2005: The On-Demand Media Consumer, p. 4.

24 Ibid., p. 20.

25 Ibid., p. 26.

ADDITIONAL READINGS

Brown, James A., and Ward L. Quaal. Radio-Television-Cable Management, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Buckingham, Marcus, and Curt Coffman. First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Certo, Samuel C., and S. Trevis Certo. Modern Management, 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2006.

Covington, William G., Jr. Systems Theory Applied to Television Station Management in the Competitive Marketplace. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997.

Daft, Richard L. Management, 7th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western, 2004.

Drucker, Peter F. Management Challenges for the 21st Century. New York: HarperBusiness, 2001.

Drucker, Peter F. Managing in a Time of Great Change. New York: Truman Talley Books/Dutton, 1995.

Herzberg, Frederick. Work and the Nature of Man. Cleveland, OH: World, 1967.

Maslow, Abraham H. Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

Robbins, Stephen P., and Mary Coulter. Management, 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2005.

Sashkin, Marshall, and Kenneth J. Kiser. Putting Total Quality Management to Work: What TQM Means, How to Use It and How to Sustain It Over the Long Run. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1993.

Wicks, Jan LeBlanc, George Sylvie, C. Ann Hollifield, Stephen Lacy, Ardyth Broadrick Sohn, and Angela Powers. Media Management: A Casebook Approach, 3rd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004.