CHAPTER 1

Understanding the Microstock Revolution

ABOUT STOCK PHOTOGRAPHY

Don’t panic. This is not a lecture on the history of stock photography, but a few words of explanation may help set the scene for what happened in April 2000 when the first microstock image library was born, signaling the beginning of a revolution in the stock photography industry.

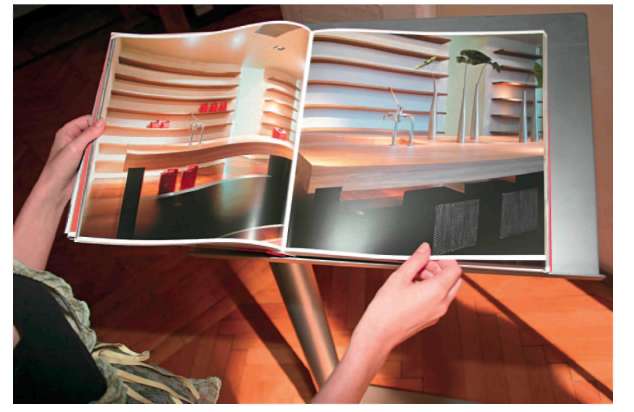

You don’t need to be told that we live in an image-intensive world. Just step in to any newdealer’s office and flick through a few magazines and books. Nearly every modern written publication is filled with images—and in the past few years, the Internet has added a whole new dimension to this insatiable demand for pictures of every kind (Figure 1.1). Most of the photos you see in books, magazines, and on the Internet were not shot specifically for a particular publication but were selected by picture editors or designers from available photographs that were in stock and ready for purchase. Of course, some images are shot to order. High-end advertising campaigns use photographers working under the direction of advertising agencies. Newspapers need newsworthy images to fill their pages.

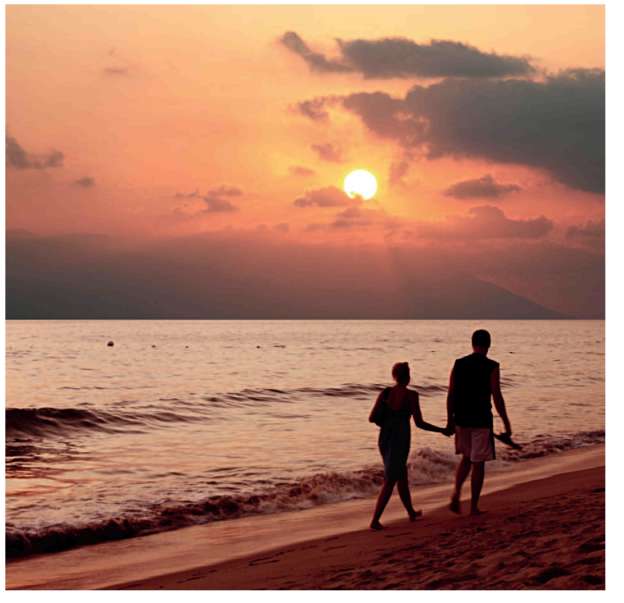

But what if you need an image of a happy couple on a beach, and it happens to be midwinter? Well, the answer is simple! Just spend megabucks on flying the photographer, his or her kit, an assistant, the happy couple, and an art director and assistant to a tropical paradise. Will the community magazine that needs that beach shot be happy to pay the cost? I don’t think so!

Or perhaps you are Web designer and you want a picture of a group of businesspeople in a boardroom. I doubt that you will be filled with joy at the prospect of hiring the models and the photographer, renting a boardroom, and arranging for lighting. But even assuming you can stretch to the considerable expense of doing so, you still might not get the shot you have in mind.

FIGURE 1.1 We live in a world with an insatiable appetite for images, as this good microstock image helps to illustrate. © Jozsef Hunor Vilhelem/Fotolia.com

Of course, you do not have to go to the expense and trouble of arranging a photo shoot for most image requirements any more than you need to hire an author to write a novel specifically for you to read on vacation. For both of these examples, there are suitable images ready for purchase at the click of a button from stock photography agencies and, specifically, from the new microstock agencies.

Of course, this sounds simple on paper, but how easy is it really in practice? To prove the point, I set myself the task of finding, within 2 minutes each, suitable images for the happy couple on the beach and the business team in a boardroom examples that I mentioned above—and here they both are, as Figures 1.2 and 1.3, sourced from among many available images in microstock libraries that might fit the bill.

I might have had similar success looking for images in a more traditional library such as Corbis, Getty, or Alamy, but the price

FIGURE 1.2 “Happy Couple on a Beach.” This image was sourced in just 2 minutes from iStockphoto—no dry run or preparation. Generic lifestyle images like this are popular as they can be used to illustrate many different concepts. © barsik/iStockphoto

would have been much higher. The images in Figures 1.2 and 1.3 cost around two dollars each. I used iStockphoto for this search, but my research shows that I could have used other microstock libraries.

FIGURE 1.3 Businesspeople in a boardroom. As with Figure 1.2, this image was found in a few moments. Although not perfect for all uses, this image is a good stock image and has a number of useful qualities we’ll cover in more detail later in the book. How many can you see? © iStockphoto

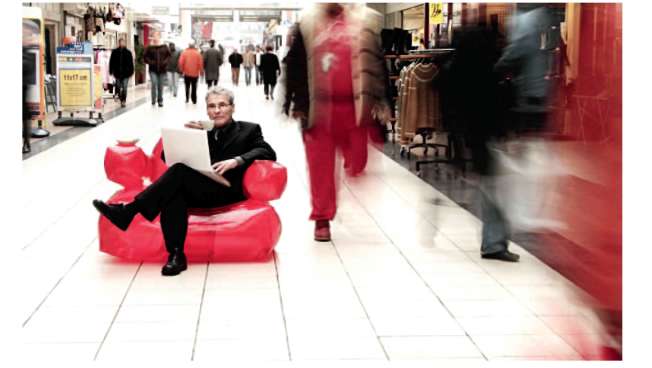

SHOP UNTIL YOU DROP

The best analogy I can think of for purchasing stock photography is going to a shopping mall to buy a new item of clothing (Figure 1.4). Unless there is a special occasion, you expect to be able to look through items already manufactured and available for immediate sale. You just browse through a catalogue (where you will see more photos—I expect you are, quite literally, getting the picture) or rifle through the items on sale.

Exactly the same principles apply to stock photography as apply to the shopping mall example. You really can shop until you drop on the microstock sites without spending a fortune.

THE EARLY DAYS

The earliest stock photography libraries relied on unused images from commercial assignments. Stock photography evolved from the mid-twentieth century onward to become an industry in its own right, with photographers specializing in supplying stock photo libraries with new work. In the predigital age, this was done by the photographers

FIGURE 1.4 Shopping without dropping? Just relax with microstock! © mammamaart/iStockphoto

submitting film originals (normally transparencies) to the stock libraries. These originals were then indexed and stored. Transparencies were drum-scanned (an expensive high-quality scanning process), and selections of new images were included in catalogues made available in hard copy to image buyers.

It is pretty obvious that the traditional process involved in producing, indexing, and promoting stock photographs was and is expensive—unavoidably so. The photographer incurs film purchasing and processing costs. The image library has to hand catalogue the images received from the photographers and to take great care of them; the library incurs further costs in periodically producing catalogues of a selection of images for review by potential buyers. I can recall visiting image libraries in the 1980s to make personal selections from their images for use by my then employers. I must have wasted a couple of hours per visit peering at transparencies on a light box before finding the right one for a project. It was no fun!

It should be no big surprise, then, that the major stock libraries could command substantial fees to license the use of images to buyers. High prices were justified by high production, cataloguing, scanning, distribution, management, and storage costs.

In the 1980s, a handful of major players grew to dominate the stock photography market, led by Getty Images and Corbis. The sales pitch remained much the same—high-quality pictures at relatively high prices. Images were not “sold” but “licensed.” The license would allow the buyer to use the image for the specific purpose or purposes agreed on with the stock library in advance. The price would be determined by a number of factors, such as image placement (front page, inside page, etc.), size, circulation of the publication, duration of the license, industry segment, and geographical spread.

The traditional licensing of images remains the backbone of the stock photography market. Many libraries offering licensed images also offer the option (at additional cost) of exclusivity so that a buyer knows the images he or she has purchased will not be used by a competitor. That can be important. However, the licensed model of image use can prove restrictive, and in the 1980s, royalty-free stock photography emerged as an alternative.

The title “royalty free” is misleading. The buyer does not have to pay royalties for each use of an image, but he or she still has to pay a fee for the image at the outset; however, once the image has been paid for, the buyer can use the image indefinitely and for multiple purposes. There are usually some restrictions, which might include limits on reselling or print runs, but the buyer has much more freedom to repeat the use of an image. The downside for the buyer is the risk that someone else might use the same image in a competing publication. There is generally no protection against this with the standard royalty-free sales model.

At the outset of royalty-free stock photography, prices were comparable to those for licensed images. The justification for this was the same as for licensed photography as the cost issues were broadly the same.

EXTINCTION OF THE DINOSAURS

Some scientists now believe that three (or more) factors led to the extinction of the dinosaurs and, thus, ultimately to the ascendancy of mammals—long-term climate change, a major meteor strike at Chicxu-lub, and volcanic activity. It is all very controversial and uncertain. I bring this up because there are similarities between this event and the emergence of microstock.

A confluence of three events has led not to the extinction of traditional stock image libraries (which, to be fair, cannot be described as “dinosaurs” at all and are in fact still thriving) but to the sudden evolutionary development of microstocks—and I think that in this example, the case is more easily established than for dino extinction. These events involve the following:

- The Internet(or, more accurately, the World Wide Web). The need for expensive catalogues of new images has almost vanished. Any buyer can search for what he or she wants online, which is where you’ll now find all the major image libraries have a presence. Many libraries have their entire image collection searchable online; others have a selection only.

- Fast and cheap (sometimes free) broadband Internet access. Anyone with a computer can access stock libraries in seconds from the comfort of the office or home. Download or order online what you want with no or little cost penalty for broadband usage. Of course, what can be downloaded can also be uploaded, and the micro-stocks have helped to pioneer the uploading of images directly to the image library database. From there, they can be checked online before being made available for sale (Figure 1.5).

- Digital cameras.With digital cameras, there are no film or processing costs to worry about. Digital cameras offer instant feedback and the opportunity to experiment and perfect technique. The cameras themselves are relatively expensive but no longer much more so than their film cousins. The quality of digital cameras is now also very high.

In short, most of the costs that justified high stock photo prices have been stripped out of the equation. The photographer no longer has expensive film and development costs. Original transparencies do not need to be hand catalogued and stored. The drum scanner and its operator are no longer required. Glossy sample catalogues do not need to be produced and distributed to clients. Photography is cheap to produce, store, catalogue (using digital databases), manage, and distribute.

Also, mirroring the development of the Internet, broadband Internet access, and digital cameras, all of which have transformed the supply chain, has been a simultaneous explosion in demand for quality images from Web designers (pro and home), home desktop publishing outfits, community magazines, and the like. The combination of a transformed supply chain, new channels to market through Web-based technology, and the evolution of new markets has inevitably shaken up the slightly stuffy world of the stock library, the more traditional of which, in my view, took too long to react to the new market dynamics. Step forward the microstocks.

FIGURE 1.5 The Internet has been key in transforming stock photography; this image is an example of a good stock graphic. © Patrick/ Dreamstime

MICROSTOCK IS BORN

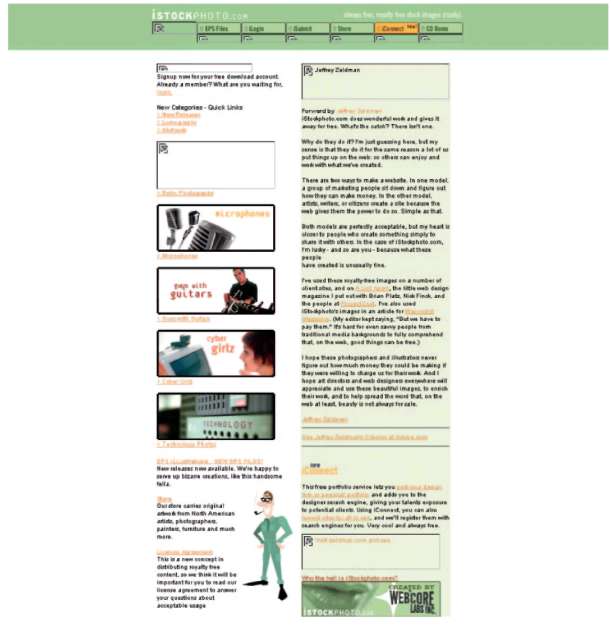

By the end of the 20th century, the market demand and the technology to serve microstock were in place. All that was needed was someone with a little perspicacity to see it. The first microstock library was founded by a Canadian, Bruce Livingstone, in Spring 2000 (Figure 1.6). Called iStockphoto, at the outset it was free (its opening strap line was “always free royalty free stock images [really]”). It remains one of the leading microstock libraries to this day. You’ll be reading a lot more about iStockphoto later in this book.

iStockphoto.com was founded in May 2000, but the groundwork was laid in 1999 with Frequency Labs Inc., my first attempt at launching a stock photography publishing company…. As an independent stock photographer I wanted to re-invent the traditional model of stock photography sale.

Bruce Livingstone, Chief Executive Officer, iStockphoto

FIGURE 1.6 An early screen capture of iStockphoto circa April 2000, shortly after its launch.

The key features of the microstock sites can be summarized as follows:

• They are based on various flavors of the royalty-free sales model—buy once, use many times.

• They have low prices, starting at around one dollar for low-resolution images.

• Pretty much everything is done online, from selecting images to payment to instant download. Much of the process is automated

• They build a strong sense of community involving artists and clients that goes beyond the seller-agent-client process.

• They are open to, and indeed often initiate, change in response to market demands. Their owners or managers are often young entrepreneurs, such as Jon Oringer of Shutterstock and Bruce Livingstone of iStockphoto.

THE OPPOSITION

If you think microstocks sound great so far, a word of caution—not everyone is happy with them. They have faced a barrage of criticism from some with vested interests in the traditional libraries. Criticisms you may hear include (and I paraphrase but, hopefully, have captured the essence of the most common complaints):

“You can’t make money from net commissions as low as $0.20 per download.” The low sale price of microstock images means an inevitably reduced per-image commission for photographers. This is, in theory (and, in my experience, in practice also), compensated for by greatly increased sales, so that you can indeed make money from microstock, despite the low per-image commission. It is more satisfying, perhaps, to sell one image once for $100 than to sell one image 200 times for a $0.50 average com mission. But do the math; the net result is the same—$100 net commission.

Feedback I have received from photographers through an online discussion group I established and run at Yahoo! (see Appendix 3 for the link) provides anecdotal evidence that their earnings from the microstocks are comparable with all but the best returns from traditional libraries. In Chapter 10, we will look in more detail at some actual case studies.

“The microstocks are destroying the livelihoods of professional photographers who rely on sales through traditional agencies.” I’m guessing that horse vendors were none too happy about the development of the internal combustion engine. The problem is that the traditional libraries have, in my view, been too slow to react to the new market reality, as outlined above. However, they are beginning to catch up, either by joining in the fun and acquiring microstock libraries, as happened with Getty buying iStockphoto and Jupiter Images acquiring Stockxpert, or in starting their own from scratch—as has happened with Corbis establishing SnapVillage in mid-2007.

Microstock pricing is subject to much criticism. Many artists with large portfolios on traditional libraries are understandably concerned that the microstocks will undermine their livelihood. So far, the evidence seems to suggest that this is not the case and that the microstocks are largely selling to new markets that previously did not have access to high-quality, affordable imagery, markets to some extent ignored by the traditional image libraries. However, it is of course true that the microstocks are making some inroads into markets dominated by the traditional libraries. Is that a criticism? I do not think it can be. Businesses compete, and in a free market economy, the fittest will survive. Also, an increasing number of professionals are using the microstocks to sell their work, so there isn’t an “us and them” world being created.

“The microstocks are full of amateur snapshots. They cannot compete on quality with the traditional libraries.” Clearly, this is a matter of opinion, so I will say only this: this book is illustrated almost exclusively with images I have selected from microstock libraries (cover shot included). Form your own opinion.

COMPARISON WITH TRADITIONAL LIBRARIES

Please note, and this is a central plank in my message to readers, I am not seeking to be overly critical of the traditional stock libraries. Many continue to enjoy impressive growth and serve loyal markets. One I will mention now and will return to later in the book is Alamy, based near Oxford, England, an “open” traditional library that sells work on both licensed and royalty-free terms. At the time of this writing, Alamy has over ten million images on its site, dwarfing the largest microstock, and has just introduced Internet-based image upload and quality control systems similar to the microstocks.

Shutterstock’s target market is very broad. We target and serve the high-end design market certainly—this includes art directors, graphic designers, book designers, advertising creatives, etc.

Jon Oringer, Chief Executive Officer, Shutterstock

There will likely always be a need for traditional licensed images, particularly where they are properly rights managed so that buyers know if and how they have been used before and can pay extra to buy exclusivity. It is just that, for many uses, buyers don’t need the bells and whistles (not to mention the expense) of a traditional licensing model.

The microstocks are, in general, all about generic imagery of all kinds. No true microstock of which I am aware specializes in just one or two particular areas. Conversely, the traditional libraries include many such niche players, often supplying highly specialized markets, such as medical imagery (http://www.caribbeanstockphotography.com), and so on. You (quite literally) get the picture. (I should add that I have no connection with these sites; I have chosen them at random to illustrate my point.)

Have a look at the paid-for stock library portal site at http://www.stockindexonline.com, and you can see for yourself the wide variety of both general and specialized stock libraries listed there. These niche libraries continue to have a role in providing top-quality images not easily found elsewhere. You may have images that are best suited to these specialized libraries. If you do, then it makes perfect sense to submit work to them. I already do. Diversify your channels to market.

In Chapter 12, we will consider the possible future of the micro-stocks and the stock photo industry generally.