Problems without owners, they say, usually become problems without solutions.

I think we use the word ‘ownership’ as a kind of shorthand for the way we relate to a problem. In this chapter, we’ll look at four levels of ownership, and how each profoundly affects the way we go about solving a problem.

In and out of control

Our ownership of a problem increases when we feel more in control.

A sense of personal control is vital for our well-being. Without it we feel uncomfortable, and may start to feel ill. Control is what you lose when you’re stuck in a traffic jam for no apparent reason. It’s what we deny people when we put them in an old people’s home or in prison. Control is what evaporates when you find yourself lost in a labyrinth of bureaucracy, or abandoned midway through a conversation with a distant call centre.

We can exert control in a situation by doing something: we can run away from a threat; store food for the future; modify our conditions to stay dry and warm. But we can also exert control mentally: if we think that we have some control, then we shall behave accordingly. If we think that we are helpless, we’ll behave as if we are helpless.

The vital thing is to feel in control.

Circles of influence and circles of concern

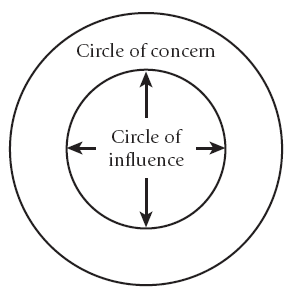

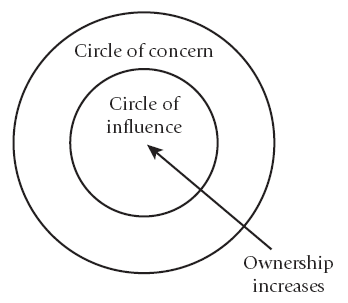

Stephen Covey, in Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, models this idea of personal control by drawing two circles, one within the other. The outer circle he calls the circle of concern: it contains all the problems we worry about, but which are outside our control (things, in his words, such as ‘the national debt, terrorism, the weather’). Within the circle of concern is the circle of influence: in this circle are all the problems over which we feel a sense of control (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Circles of influence and concern

Covey suggests that we can respond to problems reactively or proactively:

- We react to a problem in our circle of concern: we assume that we can’t change the problem itself because we feel that we can’t control it.

- We act proactively to a problem in our circle of influence: our sense of control over the situation leads us to engage with the problem and try to change it.

We choose to put problems into one circle or the other. ‘Our behaviour,’ says Covey, ‘is a function of our decisions, not our conditions.’

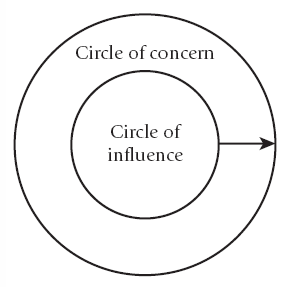

Being more effective, according to Covey, means paying attention to the right problems. It means concentrating on the problems we can control, and not on the ones we can’t. Being more effective means increasing our circle of influence (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Increasing the circle of influence

Concern, influence and ownership

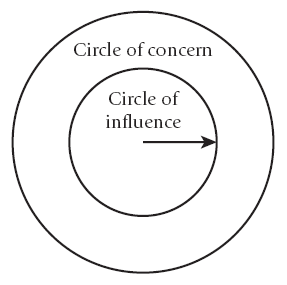

We can use Covey’s two circles to understand problem ownership. At the outer edge of our circle of concern, we feel no ownership; at the centre of our circle of influence, we experience complete ownership (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Increasing ownership

When do we place problems in our circle of concern? Perhaps we are affected by a problem but can’t understand it (like a banking crisis or global climate change). Perhaps we feel we lack the power to influence it (imagine being an employee in an organization facing meltdown as the result of a strategic error). We may feel deeply moved by a problem but unable to act (as when we see pictures of famine in a distant land).

And when do we place problems in our circle of influence? When we feel that we understand the problem adequately; and when we feel that we have all that is necessary to act to solve the problem.

What to do

Concern or influence?

Take a large piece of paper and draw the two circles on it. Think about some problems you are currently facing and write each one on a sticky note. Place the sticky notes in one of the two circles, depending on how much influence you feel you have over the problem.

Compare a problem in one circle with a problem in the other. What’s the difference? List the factors that affect your thinking about each problem.

Now pick up one of the problems in your circle of concern. Do you want to move the problem into your circle of influence? What would need to change in order for that problem to go into the circle of influence? What would you need to do? What can you do?

Four levels of ownership

The four levels of problem ownership are:

- blame,

- resistance,

- responsibility,

- commitment.

At each level, we feel different degrees of control over the problem. And the action we take will differ accordingly.

But here’s the most important idea in this chapter:

We choose the way we own a problem. And the choice we make can transform the problem itself.

Blame

Blame is the lowest level of ownership. In fact, on this level, ownership is pretty well zero.

Blame is probably one of the most common responses to problems. (How many of us work in a ‘blame culture’?) And we all know how debilitating blame can be, especially to our ability to solve problems. So we need to take a long, hard look at blame: what it is, how it arises, how it perpetuates itself and how to avoid it.

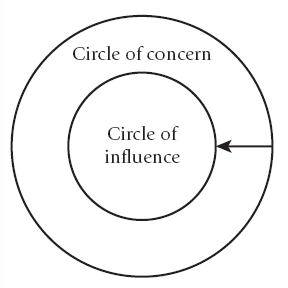

We can represent this level of ownership as an arrow in the circle of concern, pointing outwards (see Figure 4.4). The arrow is in our circle of concern because blame is a reaction to a situation over which we have no control. And it points outwards because, when we feel powerless, one of our most powerful urges is to shift ownership of the problem away from us.

Figure 4.4 Blame

The origins of blame

Blame is our natural response to feeling out of control.

Intuitive problem-solving works by matching an external stimulus to a mental model. If we can’t pattern-match – because a problem is complex, perhaps, or we can’t see what caused it – we feel out of control. The best way to regain that control is to find a credible pattern-match. And the way we do that is interesting. Our minds default to a position in which we believe that someone – or something – has created the problem deliberately. That pattern-match then gives us a clear action as a solution: punish the perpetrator.

And that’s how blame is born.

What’s interesting about blame is that we use it even when there’s obviously nobody to blame. We shout at the dog when it ‘refuses’ to obey; we kick a burst tyre. Blame sees no difference between people, animals and inanimate objects. In blame mode, we assume that everything we come into contact with is like us: human.

The principle seems to be:

When no cause is discernable, assume personal intent.

Blame is a form of magical thinking. When we feel powerless, we begin to see meanings and intentions where none exist. Blame operates like pareidolia, which we looked at in Chapter 1: stressed out by uncertainty, we start ascribing malign intentions to our partners, or to the people we work with. We hatch conspiracy theories. We blame our managers, the government, the gods, or fate.

Moving beyond blame

How do we escape the blame cycle? The first thing to do is recognize what we’re doing. We should acknowledge that blaming is a natural, intuitive response to feeling out of control. But rational problem-solving can also tell us that blame is almost never helpful as a way to approach a problem: it damages others, and it can damage us by perpetuating a sense of helplessness.

So, after recognizing what we’re doing, we can challenge our behaviour – and change it.

What to do

If you are blaming someone for a problem:

- Challenge your reasons for blaming. Stop generalizing: what makes this situation different?

- Stop using blaming solutions: making life difficult for the other person, refusing to help, copying senior management into your emails ...

- Separate the problem from the person. Tell them that you are doing so.

- Agree with the person that a problem exists. Agree a

- definition of the problem.

- Discuss who should take ownership.

- Offer help.

If you are being blamed for a problem:

- Separate the problem from yourself.

- Lower your emotional arousal before responding.

- Decide whether you are responsible for the problem’s existence.

- Look for help: someone who can see the problem

- objectively from the outside.

- Discuss the problem with the person you think is blaming you (after all, they may not be blaming you, and you may be misreading the situation).

- Decide the appropriate response: to hand over the problem, to take responsibility for the problem, or to commit to constructing a solution.

And what if you are unlucky enough to be working in a blame culture? Can you avoid being infected? It may be hard, but you can decide not to contribute to it. You can choose your conversations – whether to take part in the gossip and the backbiting, or avoid it. You can choose whether to challenge blaming behaviour or simply avoid becoming involved.

Above all, you can follow Stephen Covey’s advice and concentrate on the problems where you have some control. You can seek to increase your circle of influence.

Resistance

Resistance is the second level of ownership. Like blame, resistance reacts to a sense of powerlessness. Unlike blame, however, resistance includes the desire to do something, to take control. Without the desire, what are we resisting? It’s the friction between that desire and some other internal force that causes the resistance.

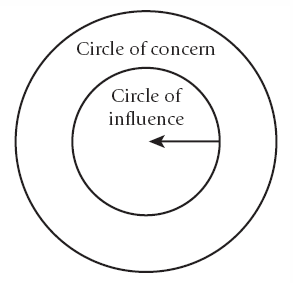

Resistance is represented in the circle of concern as an arrow pointing inwards (see Figure 4.5). The arrow remains in your circle of concern because you feel you have no influence, but it’s pointing inwards because you do want to act. You want to take ownership of the problem, but something is stopping you.

Figure 4.5 Resistance

Resistance, like blame, is a natural response to uncertainty. Unlike blame, however, resistance is static rather than active. Blame strikes out; resistance digs its heels in. Blame discharges stress; resistance increases it. Blame damages others; when we resist, we risk damaging ourselves.

Some forms of resistance are relatively minor: we’ve all put off the moment when we need to start work on a project or bring up an awkward issue with a colleague. Sometimes we engage in ‘avoidance behaviours’: making another cup of tea rather than making a difficult call; leaving the office rather than confronting a painful decision.

But resistance can go deeper, towards denial. And denial may offer a respite from stress. But persistent denial of a persistent problem is hardly going to help us solve it.

What to do

Recognizing resistance

Here are some of the key symptoms of resistance. Identify the last time you found yourself exhibiting one or more of them:

- Procrastination: putting off the moment when we need to start working on a problem; failing to turn up for meetings.

- Avoidance behaviours: finding something else to do rather than buckling down.

- Denial: failing to answer the phone or emails; missing appointments.

- Malicious compliance: being late for meetings; carrying out instructions to the mere letter; assigning a subordinate a task that undermines action to solve the problem.

‘Out of procedure’

We often resist when we’re wrenched ‘out of procedure’.

Imagine that you have spent some time learning how to operate a new computer program. You attended training sessions; you practised regularly; it wasn’t easy, but in the past few weeks you’ve finally mastered the skills and you are now ‘up to speed’.

This morning, an email appears from the IT department, telling you that the system is being abandoned in favour of a different one.

My guess is that your first response will be resistance: ‘Certainly not! After all that effort? If they think I’m going to change again, and go through that hell – they can think again ....’

We use procedural memory, as we saw in Chapter 2, to learn new skills (like operating that computer program). Procedural memories have two important characteristics:

- They must be repeated many times before they become ingrained: we have to practise.

- Once they are embedded, they are more or less permanent. Even if you don’t ride a bicycle for years, you will undoubtedly remember how to do it after a few moments.

These two features mean that procedural memories resist being modified or removed. This resistance makes sense. It’s energy-efficient: we don’t have to waste energy relearning what we already know.

The more solidly imprinted the procedural memory, the more resistant we are to modifying or replacing it. If a problem disrupts a procedural memory you’ve built up over years, the resistance may be considerable. Remember the resistance that met the idea of decimal currency or metric measures? (Some of us remember!)

What to do

What’s the procedure?

If a problem is causing resistance, it may mean that some deeply rooted procedural memory is being challenged.

Identify that procedural memory and you may be able to begin managing your resistance – which is the first step towards taking greater ownership of the problem.

What need is not being met?

A problem can also provoke resistance if it threatens a fundamental need.

We all have obvious physical needs. All human beings need breathable air, clean water, nutritious food, exercise, sensory stimulation, shelter and sleep. Any attempt to withdraw those resources can trigger resistance: a fact exploited by interrogation techniques such as sleep deprivation or waterboarding.

But we also have emotional needs, which must be met if we are to be healthy, functioning, effective people. We’re just as likely to resist a threat to one of these needs as we are to resist the threat of drowning or starving. One such emotional need, as we’ve seen, is the need for a sense of personal control. If a problem makes us feel powerless, we’re very likely to resist tackling it. And we’re also likely to resist if one of the following needs is threatened:

- security – a safe place that allows us to live and develop fully;

- attention – both from and to other people;

- emotional intimacy – knowing that at least one person accepts us for what we are;

- feeling part of a community – a family, tribe, ethnic group or nation;

- privacy – the opportunity to be alone to reflect on our experiences and make sense of them;

- a sense of status in a social group – a feeling that others value us;

- a sense of competence and achievement – that we are good at something and have made a difference somewhere;

- meaning and purpose in our lives – which may come from other people, from a belief system or from being stretched in what we do or think.

(This list of human needs derives from the work of Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell.)

Resistance might be a sign that we feel a problem threatens one or more of these needs. We might find ourselves able to take greater ownership of the problem if the need could be met or guaranteed.

What to do

Meeting the need

Identify the need that is not being met, and you may have discovered the source of your resistance.

- Security: does the prospect of tackling the problem make you feel unsafe?

- Attention: do you feel that you are not being acknowledged for your efforts in tackling the problem?

- Emotional intimacy: does the problem threaten your need for acceptance or love?

- Feeling part of a community: would dealing with the problem alienate you from your team or workmates?

- Privacy: does the problem expose some aspect of your life you wish to remain private?

- A sense of status in a social group: do you feel exploited in being asked to deal with the problem?

- A sense of competence and achievement: do you feel incapable of tackling the problem, not up to the task or afraid of failing?

- Meaning and purpose in our lives: perhaps the problem is deflecting you from what you really want to do, achieve or work for?

Reducing resistance

Different features of a problem will affect how much we resist tackling it:

- Is the problem controllable? We resist when we lack power to influence a situation – when a problem is in our circle of concern.

- How serious is the problem? We may resist the need to repair a leaking roof less than we resist the need to move house.

- How long-lasting is the problem? We resist long-term problems more than short-term ones. Indeed, our resistance may make a problem persist for longer. We may resist solving a difficult Sudoku puzzle less than we resist tackling a chronic problem such as a disintegrating relationship, debt or addiction.

- When has the problem occurred? We may resist less if the problem finds us at a good moment for solving it; we may resist more if we’re oppressed with a dozen other problems at the same moment.

- How predictable is the problem? If we can see a problem coming and plan for it, we may resist less. Surprises will probably trigger considerable resistance.

All other things being equal (which they never are), our resistance to a problem is likely to decrease if we can make the problem more controllable, less serious, more immediate or urgent and less surprising. If we can choose the moment to tackle the problem, so much the better.

Taking ownership of a problem

Recall Steven Covey’s advice. Effective people concentrate on their circle of influence. They focus their attention and energy on the problems over which they have some control, rather than the problems in their circle of concern.

Neither blame nor resistance helps you to solve problems. They might briefly make you feel better; but, if you truly want to solve the problem, you need to bring it within your circle of influence.

Moving a problem into your circle of influence may not be easy. How hard can it be to stop the virus of blame from infecting our view of a problem? (Consider employees who have been made redundant; partners going through a messy separation; communities locked in decades of mutual distrust and violence.) How difficult can it be to overcome our resistance to tackling a problem? (Ask a recovering addict, a reformed criminal or someone courageously battling disease or disability.) We should acknowledge that blame and resistance are natural responses to problems. But we are human beings; we can choose what to do.

The first step is to change the way we look at a problem. And we have many resources to help us do that.

What to do

Breaking out of blame or resistance

It’s all very well saying that we should stop blaming or resisting. But how can we do that?

Here’s a simple technique that’s guaranteed to get some kind of result. We’ll be looking at it in more detail later, but it might be useful to introduce it right now – as first aid to help you overcome blame or resistance.

The technique is this:

Express the problem as a phrase beginning with the words ‘how to’.

And – um – that’s it. I said it was simple.

But notice what happens when we express the problem as a ‘how to’. Instantly, the problem is no longer something wrong but something we are thinking about doing. The focus is no longer on the situation, and instead is on what you can do – it enables you to start to take ownership of the problem.

‘How to’ is a remarkable technique. We’ll find out a lot more about it in Chapter 8.

Responsibility

Responsibility is the third level of ownership. On this level, we have moved from reacting to a problem towards taking a proactive approach to it. With responsibility, we have activated our desire to act on a problem.

Responsibility is ownership of a problem conferred on you by others. You can represent responsibility as an arrow in your circle of influence, pointing outwards (see Figure 4.6). The arrow is in your circle of influence because you feel you can take action on the problem; it’s pointing outwards because your sense of responsibility is towards another person, or to other people.

Figure 4.6 Responsibility

Responsibility and presented problems

It’s at this level of ownership that problem-solving proper begins. Once you take the problem into your circle of influence, you begin to assume some level of control over the problem. When you take responsibility for a problem, you feel that the problem has been presented to you and it’s your task to deal with it. So I call problems on this level of ownership presented problems.

Presented problems: key characteristics

- They happen to us. We aren’t responsible for their existence. (So they are not our ‘fault’.)

- They are usually expressed as a statement about what is wrong.

- We see them as an obstacle in our path.

- There is a perceived gap between what is and what should be.

- Solving them involves effort.

My guess is that most of the situations we regard as problems are presented problems. Most of the tasks on a ‘to-do’ list – all the chores of an ordinary working day – are likely to be presented problems. They’re problems for which you take responsibility, but you might see them as obstacles stopping you from doing what you really want to do.

Because presented problems are your responsibility, one of your main priorities might be to discharge that responsibility as efficiently as possible. You want to cross the problem off your ‘to-do’ list, get it out of the way and move on. Once you’ve solved it, you’d prefer a presented problem not to reappear. You may well find yourself, therefore, wanting to ‘fix’ presented problems: to look for the solution that removes the problem permanently. Unfortunately, one presented problem may well be followed by another; and before you know it, you’re ‘fire-fighting’.

You may work in an organization where fire-fighting is accepted as the norm. Most organizations, after all, have more problems than people to deal with them. If responsibilities aren’t managed properly, problems will be ‘patched’ – in other words, temporarily fixed – while everyone learns to juggle ever more furiously. Managers who patch and juggle well may be highly praised; but such heroics can carry a heavy cost in terms of increased stress, burnout – and fewer problems actually solved.

What to do

Do you work in a fire-fighting culture?

Tick the boxes that apply to your organization.

![]() We have more problems than problem-solvers.

We have more problems than problem-solvers.

![]() Many problems are patched rather than solved.

Many problems are patched rather than solved.

![]() Many patched problems create new problems.

Many patched problems create new problems.

![]() Many patched problems recur and need re-patching.

Many patched problems recur and need re-patching.

![]() We regularly interrupt long-term work to address urgent problems.

We regularly interrupt long-term work to address urgent problems.

![]() We often solve problems at the last minute, using heroic efforts that are highly applauded.

We often solve problems at the last minute, using heroic efforts that are highly applauded.

![]() Fire-fighting causes drops in levels of performance.

Fire-fighting causes drops in levels of performance.

![]() Fire-fighting creates stress among staff.

Fire-fighting creates stress among staff.

![]() Many people here would say that fire-fighting is a core feature of their work.

Many people here would say that fire-fighting is a core feature of their work.

![]() The CEO and other senior managers are continually juggling and changing priorities.

The CEO and other senior managers are continually juggling and changing priorities.

![]() We run ‘away days’, retreats or long all-staff events to focus on long-term problems, but rarely implement the solutions.

We run ‘away days’, retreats or long all-staff events to focus on long-term problems, but rarely implement the solutions.

If you’ve ticked two or more statements, fire-fighting is probably a feature of your organization’s culture. If you’ve ticked three or more, it’s probably endemic.

You may not be able to change your organization’s culture. But you can start looking after yourself – and you may need to do so, for your own well-being. Take charge of your responsibilities and manage them more effectively.

Responsibility as a contract

Responsibility is always socially determined. To have a responsibility is to have an obligation to another person, to a group or to society. After all, it’s other people who hold us responsible for our actions. To carry out your responsibilities is to deserve praise or reward; if you fail to discharge them, you can expect to be criticized or punished.

To be responsible is to enter into a kind of contract. Indeed, we often use the language of commercial or legal obligation to explain our responsibilities. We might speak of honouring our responsibilities, for example, in the same way that we must honour a bargain. We discharge a responsibility, in the same way that we might discharge a debt. To be accountable means that someone can hold us to account for our responsibilities: that we may have to pay, literally or metaphorically, if we fail to discharge them. Indeed, we might say that we’re liable for the responsibilities we take on; that liability is a measure of the extent of our responsibility, or of the price we might have to pay for failing to honour it.

Responsibilities, like all contracts, have limits. Once you’ve discharged your responsibilities, paid your liabilities, done what you’re accountable for, your ownership ceases – and you can walk away.

Taking on a responsibility, like signing a contract, must be a free act. To be truly responsible for tackling a problem, you must be free and able to choose what to do. To be compelled against your will to do something arguably absolves you of responsibility: hence the appeal by those who claim, after committing horrific acts, that they ‘were just following orders’.

But freedom is as much psychological as political. Free will is the essence of responsibility. To be responsible for one’s actions is to know what one is doing, to be able to reflect on that action – and to be able to choose not to do it. Indeed, the law assumes that some people – the young or the mentally ill, for example – can’t take responsibility for their own actions, and therefore can’t be held legally responsible for any criminal acts they commit.

Taking on a responsibility, therefore, carries with it a paradox. On the one hand, a responsibility is a duty or an obligation towards others; on the other, it’s something we take on freely, by our own choice.

We live this paradox every day. If a manager, a teacher, or a parent complains about the weight of their responsibilities, they are likely to be told: ‘Why complain? You chose these responsibilities; you made a contract; you’re enjoying the benefits that come with the job. You’re free to walk away.’ Which may, or may not, be true. Our choices carry consequences, some of which we may not be able to escape.

The perils of responsibility

Taking responsibility for a problem brings inevitable risks. We’re taking on a problem on behalf of somebody else; we’re agreeing to honour an obligation without having been entirely free to define it. As a result, problems for which we take responsibility often share certain troubling features:

- Unclear goals. The person handing responsibility to you may not know precisely what they want you to do, or – even more troublingly – what they don’t want you to do. A problem might start small and grow unexpectedly; it might start simple and get horribly complicated.

- Lack of control. If we had complete influence over what to do and how to do it, we’d be happier. But your obligations to others may limit the control you can exercise.

- Lack of immediate feedback. You may have to check with others about aspects of the problem: information, deadlines or criteria of success. And those people may be unavailable.

- A mismatch between challenge and skill. You often have to assume responsibility for problems that are trivially easy, boring and tedious (call them chores). You may have to take responsibility for problems that are mind-numbingly difficult (we’ll call them headaches in the next chapter). And you can’t simply ignore your responsibilities just because they’re tedious chores or stressful headaches.

- Distractions. The working day’s full of them. It’s often impossible to concentrate on one task at a time. When was the last time you completed a job without being interrupted by another?

- You’re accountable. Your child expects dinner to be on the table. The customer needs an answer. Your manager is waiting for the quarterly figures.

- You have to think about causes and consequences. How did the problem get this complicated? Do I have authority to do what I want to do? What if ...?

- You’re pressed for time. Every new problem is another demand on your time. It’s hard to concentrate if you’re clock-watching.

- What’s in it for me? If you can see a clear reward at the end of the job, you might feel better. When were you last thanked for solving a problem? And is solving this problem part of your job description, anyway?

Given all these complexities, it would hardly be surprising if you found yourself resisting your responsibilities, or lapsing into fire-fighting.

What to do

Setting the bounds of responsibility

Think of a responsibility as being like a contract. The best way to honour a responsibility is to know beforehand precisely what you’re taking on. One way to clarify all this is to use Rudyard Kipling’s famous serving men: the six Ws:

- Why? What’s the overall objective in tackling this problem? What outcome are you being expected to achieve? Do you have SMART goals (are they specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely)?

- Who? To whom are you accountable? And for whom are you accountable?

- What? What precisely is the problem you’re taking on? How well do you understand it? How well defined is it? (The analytical tools we’ll examine in the next chapter will be critically important in answering these questions.) What actions are you being called upon to carry out – exactly?

- When? Is there a deadline? Are there milestones that you will be expected to hit?

- Where? Where will your solution have an impact? How far does your responsibility stretch? Where are its boundaries or limits?

- How? What authority have you been granted? What are you permitted to do – and what do you need to ask further permission to do? What constraints will you be expected to operate under? What resources are available to you? What support can you count on?

Commitment

Commitment is the fourth and highest level of problem ownership. On this level, the problem is so firmly within our circle of influence that we feel we’ve created the problem ourselves: we’re responsible for its very existence.

Commitment can be represented in your circle of influence, as an arrow pointing inwards (see Figure 4.7). The arrow is in your circle of influence because you have complete control over the problem – including how it’s defined, and what you choose to do. The arrow points inwards because your ownership of the problem is complete and unconditional.

Figure 4.7 Commitment

Problems at this level of ownership are the problems you want to have. They are the problems you leap out of bed to solve. It might be winning a sailing race on a windless day; it might be painting the sunset before it fades; and, yes, it might be catching that potential customer before the competition gets there. Indeed, you may feel that you’ve actually brought the problem into existence yourself: you’ve set yourself the problem and you’ll stop at nothing until you’ve solved it. For this reason, I call problems at this level of ownership constructed problems.

Commitment and constructed problems

Constructed problems are the problems we search out, the problems we choose, the problems we create. We might not even call them problems – we might call them challenges or projects. A constructed problem isn’t so much an obstacle on our path as the reason for taking the journey. Constructed problems ‘turn us on’.

Constructed problems: key characteristics

- We create them. They didn’t exist until we thought of them. We are responsible for their existence.

- They can be expressed as a phrase beginning with the words ‘how to’.

- We see them as the reason for doing something.

- There is a perceived gap between what is and what could be.

- Solving them is energizing.

Solving a presented problem is discharging a responsibility; solving a constructed problem is an end in itself. Presented problems are goal-oriented: we solve them in order to achieve some other objective. Constructed problems, in contrast, are autotelic: they’re worth solving for their own sake.

Finding the flow state

When you commit fully to a constructed problem, you might find yourself in a heightened mental state. You might talk about being ‘totally immersed’ in the problem, or being ‘in the zone’. The condition has been investigated in great depth by the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, who famously calls it ‘flow’.

Csíkszentmihályi (his surname is pronounced ‘chicks send me high-ee’) began to study the phenomenon in the 1960s. He observed artists while they painted, fascinated by the concentration with which they worked. He was prompted to ask: what is happiness? What do we feel when we’re happy? Why do some activities make us happy when others don’t? How could we increase our stock of happiness?

He spent the next 30 years investigating these questions, looking at people around the world: elderly Korean women, Navajo shepherds, Japanese teenage motorcycle gang members, assembly-line workers in Chicago. What motivated these people was the quality of the experience they had while doing what they did: an experience characterized by joy, concentration, a sense of mastery and a lack of self-consciousness. It was an experience that ‘took them out of themselves’; they felt that they had grown as a result of it.

And it was this experience that Csíkszentmihályi called ‘flow’. Flow, he says, is ‘the way people describe their state of mind when consciousness is harmoniously ordered’. Csíkszentmihályi noticed that the flow experience had a number of consistent features:

- Loss of self-consciousness. People took no account of how others saw them. Their attention was solely on what they were doing.

- Action merges with awareness. People took no account of the past or the future. The possibility of failure didn’t occur to them. They were living and working entirely in the present.

- A distorted sense of time. As the saying goes, ‘time flies when you’re having fun’.

- Intrinsic reward. There was no thought for any compensation, payment or recognition for the work.

This ‘optimal experience’, as he called it, didn’t happen when people were relaxing; and it certainly didn’t happen when they were consuming food, alcohol or drugs. Instead, it seemed to require an activity that stretched their capacities – something difficult, risky or even painful. The task usually involved discovery, novelty or creativity. And it was something people chose to do.

In other words, they were tackling a constructed problem.

Now, tackling a constructed problem may not guarantee you the legal high of the flow experience. But it probably will do so if a number of key elements are in place:

- Clear goals. You know what you want to achieve and you know that you can achieve it.

- Control. You feel that you’re completely in charge of what you’re doing.

- Immediate feedback. Success and failure at any point are vividly clear, so that you can adjust your behaviour quickly.

- A balance between challenge and skill. You feel that what you’re doing is neither too hard nor too easy.

- Concentration. Your attention is focused exclusively on the task in hand.

Flow is good for us. It produces intense feelings of satisfaction and enjoyment. Flow improves our performance and helps us develop our skills. Flow motivates us to grow in competence and self-esteem. All of which must be good for our health.

How can we increase our commitment?

Life can never be wholly a matter of following our commitments. We all have responsibilities that we must discharge: presented problems that we must deal with.

And our sense of problem ownership can shift. A constructed problem can easily become a presented problem. What started out as an exciting challenge can become a burden; you can become distracted, lose your sense of mastery or control in the situation. But, by the same token, you can choose to transform some presented problems into constructed problems. In fact, just about any activity can be made autotelic. As Csíkszentmihályi said in an interview:

“Talking to a friend, reading to a child, playing with a pet, or mowing the lawn can each produce flow, provided you find the challenge in what you are doing and then focus on doing it as best you can.”

Flow, then, isn’t something that happens to us; it’s something we can make happen. If you can influence your ability to focus, to concentrate, to set yourself goals or seek feedback on your performance, you can turn some of your responsibilities into commitments and take fuller ownership of the problem.

‘In many ways,’ says Csíkszentmihályi, ‘the secret to a happy life is to learn to get flow from as many of the things we have to do as possible.’

In brief

‘Ownership’ is shorthand for the way we relate to a problem. Our sense of ownership increases as we feel more in control.

We can identify four levels of ownership:

- blame,

- resistance,

- responsibility,

- commitment.

Blame and resistance tend to arise when a problem is in your circle of concern. Responsibility and commitment tend to arise when a problem is in your circle of influence.

Blame is a reaction to feeling out of control. Its guiding principle is: when no cause is discernable, assume personal intent.

To escape the blame cycle: recognize what you’re doing; use rational problem-solving to change your sense of ownership.

Resistance is also a reaction to feeling out of control. We often resist when we’re wrenched ‘out of procedure’. A problem can also provoke resistance if it threatens a fundamental need.

We resist less if a problem is controllable, minor, immediate or urgent and unsurprising.

Responsibility is ownership of a problem conferred on us by others. At the level of responsibility, we see problems as presented.

To be responsible is to enter into a kind of contract. The best way to honour a responsibility is to clarify it precisely, using Kipling’s famous serving men: the six Ws.

Commitment is a proactive stance, in which we choose or even create a problem. Problems at this level of ownership are constructed.

Committing fully to a problem puts us into a ‘flow’ state. You can create the ‘flow’ state: if you can focus more, set yourself goals or seek feedback on your performance, you can turn some of your responsibilities into commitments.