Chapter 7. Alignment

USUALLY WHEN WE SPEAK OF alignment of type, we’re referring to the horizontal position of text within a text frame. Each of the basic options—left, center, right, and justified—creates its own vibe, has its own strengths, and asks to be treated in particular ways to avoid common shortcomings. In this chapter, we’ll look at the horizontal and vertical alignment of type within a text frame.

Horizontal Alignment

There are several terms for the different alignments in common usage. What InDesign refers to as Left alignment is also known as ragged right, flush left, or (confusingly) left justified. In InDesign terms, with Left Justify alignment all lines of the paragraph are the same length, except the last line. InDesign offers two other flavors of justified type, which have limited utility: Center Justify and Full Justify. The difference between them is the way the last line of the paragraph is handled. When I refer to justified type, I mean type with the last line of the paragraph left aligned.

Ragged can refer either to left-, center-, or right-aligned type. “Align towards spine” aligns text on a left-hand page so that it is right aligned. If the same text flows onto a right-hand page, it becomes left aligned. “Align away from spine” does the opposite: Text on a left-hand page is left aligned, while text on a right-hand page is right aligned.

Because the length of every line will vary, an important distinction between the four main alignment types is what happens to the extra space on the line. With ragged alignments, the word spacing is consistent. Every word space is the same width as every other word space in the paragraph. The extra spacing is allotted to the right edge of the column (left alignment), allotted to the left edge (right alignment), or divided equally between the left and right edges (center alignment). With justified alignment, the size of the word spaces varies so that the lines can all be the same length. However, to maintain even type color when working with justified type, we strive to maintain the illusion that all our word spaces are the same.

Left Alignment

With left-aligned type, each line starts at the same place. The word spaces are consistent, giving the text block an even type color. The lines are of varying length, adding shape and interest—as well as white space—to what would otherwise be a rectangular block. The asymmetry of left-aligned text can appear informal because it resembles the uneven line lengths of handwriting.

When using left alignment, pay attention to the shape of the rag—the uneven side. The rag shape is determined by the column measure, the nature of the text (whether it contains predominantly long or short words), and whether hyphenation is turned on. Ideally, the rag should modulate subtly, without any sudden “holes” or awkward shapes. The line lengths should be clearly irregular (i.e., they shouldn’t look like carelessly set justified type), but not so irregular that they create distracting shapes that slow reading. A bad rag occurs when some lines are too long and others too short, which can be distracting. To prevent this, you can shape the text manually by using forced line breaks or discretionary hyphens, or by preventing certain phrases, product names, and Web addresses from breaking over a line by applying No Break; see Chapter 9, “Breaking (and not Breaking) Lines, Paragraphs, Columns, and Pages.” You can also, if necessary, apply a modest amount of tracking to cause a paragraph to rag differently.

Figure 7.1 The four basic types of horizontal alignment: left, justified, center, and right.

A paragraph style option called Balance Ragged Lines attempts to give you lines of roughly equal length. This is useful for heads and subheads and will reduce the amount of manual intervention necessary (in the form of forced line breaks, or nonbreaking spaces), but you’re still going to need to check the type carefully for meaning. Balance Ragged Lines won’t always break the line where you’d like it to. It’s the designer’s responsibility to make sure the lines break in a way that accentuates, rather than detracts from, the meaning of the text.

When applied to body text, Balance Ragged Lines can create more problems than it solves. Once multi-line paragraphs have Balance Ragged Lines applied to them, manually trying to make the lines of those paragraphs break how you want them to will be difficult. Balance Ragged Lines has no effect in justified text.

Figure 7.2 Hyphenation affects the rag of left-aligned text, as shown by the blue rectangles at the end of each line. The paragraph on the right is hyphenated; the one on the left is not, resulting in a harder rag (more variation in the line lengths).

Figure 7.3 Applying Balance Ragged Lines to heads and subheads ensures lines of roughly equal length.

Justified Alignment (Justified with last line aligned left)

On every line of type, there is leftover space. With justified type, where the text is flushed left and right, that extra space is necessarily elastic—distributed between the word spaces and (potentially) between the letter spaces to give lines that are exactly the same length.

Justified type is symmetrical; the smooth edge on the right side of the columns creates a sense of balance. The uniformity of the right-hand margin also gives a more formal look to your page. Justified type is more economical than ragged type because it allows you to fit more words on the page. The difference may be insignificant in a short document, but in a magazine or book, it can mean a difference of several pages. All too frequently, justified type is set in columns that are too narrow, resulting in what Robert Bringhurst refers to in The Elements of Typographic Style as “white acne or pig bristles: a rash of erratic and splotchy word spaces or an epidemic of hyphenation.” However, if you have enough characters on every line (typically 40–60), and you use appropriate Justification and Hyphenation settings, there’s no reason why you can’t achieve even color with justified type.

Figure 7.4 The same paragraph set as left aligned (left) and justified (right).

How InDesign Justifies Type

InDesign’s justification settings are best applied with a paragraph style, but can also be applied on a paragraph-by-paragraph basis by choosing Justification from the Control Panel menu.

Justification is achieved by varying the size of the word spaces on the line—or in the entire paragraph—in an attempt to get even word and letter spacing, or at least word and letter spacing that looks even. There are three important options that you can set to determine how InDesign justifies type: Word Spacing, Letter Spacing, and Glyph Scaling. Using InDesign’s Justification options makes a dramatic difference in the appearance of your type.

If justification can’t be achieved by adjusting word spacing alone, then InDesign adjusts the letter spacing according to the Minimum, Desired, and Maximum settings that you choose in the Justification Options dialog. After that, it moves on to the Glyph Scaling settings.

Figure 7.5 Justification settings applied as part of a Paragraph Style (top) and locally through the Control Panel menu (bottom).

Figure 7.6 This figure shows my preferred settings for justified type. Allowing a small variation (± 2%) in Letter Spacing and Glyph Scaling (± 3%) dramatically improves type color. The paragraph on the left has default Justification settings applied; the paragraph on the right has my custom settings applied. Note the variation in the width of the word spaces, indicated by the blue shapes below.

The more words there are on the line, the more word spaces there are to adjust, and the less noticeable those adjustments will be. You get more words either by making your type smaller or your column wider. It’s a balancing act: If you make your column too wide relative to your type size, you’ll be swapping one evil for another.

Tip:

Even if your body text is justified, other elements of your text will want to be ragged, both to avoid composition problems and to provide a contrast to the symmetry of your justified type. The following elements should not be justified: headlines and subheads, bylines, tables of contents, captions, pull quotes, footnotes, bibliographies, and indexes.

Word Spacing

No prizes for guessing that this refers to the space between words—the width of space you get when you press the spacebar.

Determining word spacing is more of an aesthetic consideration than an exact science. A good starting point is 100 percent, which is the width of the space-band specified by the font designer. However, you may want to reduce this to 90 percent or even less when working with any of the following:

• Condensed type

• Typefaces in light weights

• Typefaces that are tightly fit (if you have tight letter spacing, you’ll want your word spacing to be correspondingly tight)

• Display type

Letter Spacing

This is the distance between letters and includes any kerning or tracking values that may be applied to the type. A character’s width is determined not just by the character itself, but also by the space that the font designer adds around the character—known as the side bearing.

Because there are more letter spaces than word spaces on every line, changing the spacing between the letters by an imperceptible amount—plus or minus 2 percent—can dramatically improve the evenness of justified type.

Tip:

With both Word Spacing and Letter Spacing you need to find a balance between being strict and being reasonable. There’s no point in specifying restrictive settings if your text-to-column width ratio makes it impossible for InDesign to honor these settings.

Glyph Scaling

Glyph scaling is the process of adjusting the width of characters in order to achieve even justification—and a little glyph scaling goes a long way. Glyph scaling might sound like the kind of crime that the Design Police will bust you for in a heartbeat. In reality, though, moderate amounts of glyph scaling can—combined with your other Justification settings—improve type color significantly. Moderation is the key: Keep your Glyph Scaling settings to 97%, 100%, and 103% for Minimum, Desired, and Maximum, respectively. No one will ever know that you varied the horizontal scale of your type. They will, however, appreciate the splendidly even word spacing.

Note:

It’s important to bear in mind that InDesign’s Justification and Hyphenation features work in conjunction with each other. Good word spacing will not be achieved by using the Adobe Paragraph Composer alone, but rather by combining it with the other justification features in InDesign’s toolkit.

The Adobe Paragraph Composer

A mainly behind-the-scenes InDesign feature that plays an important role in determining how the lines of paragraphs break is the Adobe Paragraph Composer. Before InDesign, page layout programs composed paragraphs line by line. Because there is a limited number of word spaces across which the extra space at the end of the line can be distributed, this often caused bad type color. Using the Adobe Paragraph Composer (the default choice of Composer), InDesign analyzes the word spaces across a whole paragraph, considers the possible line breaks, and optimizes earlier lines in the paragraph to prevent bad breaks later on. Looking at the whole paragraph is crucial because there are more places where space can be added or subtracted before this becomes noticeable. The result: fewer hyphens and better spacing. The Adobe Paragraph Composer works for both ragged and justified type, but it’s with the latter that you really see its benefits.

As fabulous as the Adobe Paragraph Composer is, don’t expect miracles. Good type color doesn’t come easy, and you’ll still have to fix some composition problems manually. This is where the Composition preference Show H&J Violations comes in handy. This preference allows you to easily identify problems so that you can fix them—by any means necessary. As a final reality check, keep in mind that even with the most carefully considered column widths, the most scientifically proven justification options, and the most judicious use of InDesign’s Composition preferences, spacing problems still occur from time to time. So don’t fire the proofreader.

Tip:

When you are editing text composed with the Adobe Paragraph Composer, the type before and after the cursor moves. While you’re editing the text, the paragraph is in progress, and InDesign is figuring out how to compose the paragraph, adjusting spacing and line breaks on the fly. This can be a little disconcerting if in a previous draft your client has signed off on specific line breaks. Line endings that change without apparent reason can make clients nervous, and they may require the whole text to be read again to make sure nothing is lost. If it’s important to your workflow to maintain the line breaks as they are from one iteration of the document to the next, consider switching to the Single Line Composer.

Figure 7.7 Choose Preferences > Composition and select H&J Violations to show spacing problems highlighted in yellow. The darker the yellow, the worse the problem.

Figure 7.8 The Adobe Paragraph Composer (left) versus the Single Line Composer (right). For the text composed with the Paragraph Composer, there are minor spacing problems on lines 8 and 9. For the text composed with the Single Line Composer, there is a major problem on line 9.

Centering Type

Center alignment assigns extra space on the line equally to the left and right of the type, giving equal weight to both ends of the line. It is widely used in magazine design for crossheads and in book design for title pages. It is also associated with birth announcements, wedding invitations, and … gravestones. Centering works best with a single line or a short paragraph; centering long paragraphs is usually a bad idea because every line has a different starting point, making the text less readable. When done right, centering can be formal and classical, and give an interesting shape to your text block; when chosen as a fall-back option, it makes layouts appear stodgy or generic. The equal white space on either side of every line makes the text feel static, as if it were being held in a vice-like grip. Beginning designers often gravitate toward center alignment because they are more comfortable with its solidity—each line is supported on either side by white space.

Figure 7.9 The same text centered (left), centered with Balance Ragged Lines turned on (center), and with the lines broken for sense using forced line breaks (Shift+Return).

Figure 7.10 Centered heads appear misaligned if the first line of text that follows does not fill the full measure (left). To compensate, the value of the extra space at the end of the line is added as a right indent to the head (right).

Combining center alignment with other types of alignment also has its drawbacks. The even white space on both sides of the line may create a symmetry that is at odds with the asymmetrical nature of the ragged-right text that follows. Centered display type over left-aligned body text will not appear optically centered if the first line of body text spans less than the full column measure. This is fixable, but even so, this difference in alignment diminishes the visual connection between the heading and the body text. Worse still would be to center an italic headline over roman type: The slant of the italic will make the headline appear off-center.

There’s no reason why centered type can’t look good, but it requires more than just clicking the Center Alignment button. The way the lines break may undermine the meaning of the text as well as create an ugly paragraph shape, so be prepared to wade in and add forced line breaks (Shift+Return) wherever necessary to carry the words that are to the right of the cursor down to the next line. Line breaks should enhance the meaning of the text as well as emphasize the central axis of the text—it should be obvious to your reader that the type is centered and not just badly justified.

Right-Aligned Type

Right-aligned, or flush-right, type is seldom used and is thus distinctive. It can be effective for short bursts of text like captions, pull quotes, or sometimes headlines. When used in a spread, it tends to work better when used on the left-hand page, when the text is “facing in” toward the spine, rather than the right-hand page facing out toward the outside margin, which can make your type look like it’s trying to escape from the page.

If right-aligned text is overused, it can be offputting to the reader because the eye ends up focusing on the end rather than the beginning of the line. Also, the ragged edge makes it harder to find the start of the line. Applied thoughtfully, however, right alignment can be dynamic and a welcome change of pace.

Right-aligned text draws attention to itself. If you’re going to use it, capitalize on this and emphasize, rather than play down, the unevenness of the rag. Just as with center alignment, this requires manually breaking the lines with forced line breaks (Shift+Return). Make sure to turn off hyphenation in right-aligned type: You don’t want the smoothness of the flush right edge disturbed by hyphenation stubble.

Other Justification Options

As well as the usual justification options, there are also lesser-used options that may be appropriate in specific situations.

Figure 7.11 Right alignment juxtaposed with justified text columns.

FIGURE 7.12 On this facing pages spread, the picture captions are aligned toward the spine, while the page numbers are aligned away from the spine.

Align Towards and Away from Spine

These options ensure that the alignment of your type mirrors itself when moved from a left-hand to a right-hand page or vice versa. For example, if you want picture captions that are right aligned on the left-hand pages and left aligned on the right-hand pages, choose Align Towards Spine. If you want page numbers that are aligned to the outside margins of facing pages, choose Align Away from Spine.

Justify with Last Line Aligned Center

This is a once-in-a-blue-moon alignment option, occasionally useful for poetry and for creating interesting shapes with text blocks.

FIGURE 7.13 Justify with last line aligned center.

Full Justify

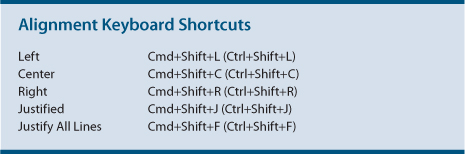

This alignment option will justify all the lines of a paragraph, even the last line. It is useful when you want display type to inhabit a fixed horizontal space. Set the alignment to Full Justify (Cmd+Shift+F or Ctrl+Shift+F) and then incrementally increase the point size (Cmd+Shift+> or Ctrl+Shift+>) to see how big the type can get before falling out of the text frame. When you go too far, press Cmd+Z (Ctrl+Z) to back up to your last step.

FIGURE 7.14 Use Full Justify to spread the type over the full column measure.

FIGURE 7.15 Side-by-side paragraphs, where the right-aligned text is an anchored text frame.

Combining Left and Right Alignment

Combining a right-aligned caption with a left-aligned column can be a visually effective use of white space. This involves creating a separate text frame for the right-aligned caption text and positioning it to the left of the main text frame. To maintain the visual relationship between the two types of text, it’s necessary to anchor the caption text frame to a specific point in the text. Here’s how:

- Cut the caption text frame (Cmd+X/Ctrl+X).

- Insert the Type cursor at the beginning of the paragraph that you want to anchor the caption to, and choose Paste (Cmd+V/Ctrl+V).

- To adjust the position of the caption, with the caption frame selected right-click or choose Object > Anchored Object > Options. Make the Reference Point the upper-right corner, the X Relative to the Text Frame, with an X Offset that is the space you want between the caption frame and the main text frame. The Y should be Relative to the Line (Cap Height), with an Offset of o. Optionally, check Prevent Manual positioning to prevent the relationship of the caption frame and main text frame from being disturbed.

“Movie credits” alignment is best achieved by converting your text to a table with the right-aligned text in the left column and the left-aligned text in the right column. See Chapter 10, “Tabs, Tables, and Lists.”

Figure 7.16 “Movie credits” alignment: right-aligned next to left-aligned text on a central axis.

Hanging Punctuation

Hanging punctuation is a form of optical alignment applied to maintain the clean left edge of the text. Hanging punctuation is used for bulleted and numbered lists (see Chapter 10), but it is also appropriate for display text—especially pull quotes and callouts that begin with a quote mark. Because the opening quote mark creates an optical hole on the left edge of the text, it’s preferable to hang the punctuation using the Indent To Here character: Cmd+ (Ctrl+). This invisible character indents all subsequent lines in the paragraph to the insertion point.

Figure 7.17 Top: A quotation in which the opening quote mark is not hanging. Bottom: The Indent To Here character is inserted after the opening quote mark.

Vertical Alignment

Type alignment usually refers to horizontal alignment of text. InDesign also has options for the vertical alignment of type. The default is for type to begin at the top of the frame, which is appropriate in most instances. There are times when Center or Bottom alignment of type within a text frame is necessary, however. With a text frame selected or your cursor inserted in the text, press Cmd+B (Ctrl+B).

Figure 7.18 The four types of vertical alignment within a text frame.

Figure 7.19 Aligning pictures to the top of the text frame results in picture and text being visually misaligned (top). Instead, align the top of the image to that (bottom).

Top Alignment

The First Baseline Offset options (Object > Text Frame Options > Baseline Options or Cmd+B/Ctrl+B) determine the start position of the type in the text frame. Rarely is there reason to change from the default of Ascent, especially because using a baseline grid overrides these options, effectively giving the same result as choosing the Leading option. It is important to note, though, that there will be a small amount of space between the top of the text frame and the top of the first line of type. This means that aligning the top of a text column to the top of a picture requires special attention. The solution is to draw a guide to the cap height of the text and align the top of the picture to that. See Chapter 14, “Pages, Margins, Columns, and Grids.”

Figure 7.20 The text is vertically centered within the text frame, but visually appears far from it (left). The text is optically centered by applying a positive amount of baseline shift to the text (right).

Center Alignment

When centering vertically, the text may not appear to be optically centered, especially if there are few or no descenders. The solution is to shift the vertical position of the text with baseline shift.

Aligning Type in a Circle

When you create text inside a circle, it may be easier to work with the text frame and the circle shape as two separate elements. Here’s how:

- Size the text to your liking.

- Select the text frame and choose Fit Frame To Content (Cmd+Alt+C/ Ctrl+Alt+C) to have the frame fit snugly around the type.

- Select both the text frame and the circle, and align the two frames horizontally and vertically using the Align panel. If necessary, adjust for optical alignment.

- Group the two items together with Cmd+G (Ctrl+G).

Figure 7.21 To create text inside a circle, it may be easier to work with the text frame and the circle shape as two separate elements.

Bottom Alignment

Bottom alignment is useful for picture captions to ensure that the baseline of the caption is aligned with the bottom of the picture in the adjacent column.

Justified Vertical Alignment

Justified vertical alignment can be used to force text to fill a vertical space or, with multiple columns, to make the text “bottom out” by adding extra space above the paragraphs and potentially to the leading of the shorter column.

This feature is highly convenient, and I use it when I think no one will notice or time is tight. But using vertical justification is something of a Faustian bargain. Yes, it makes your columns end on the same baseline, but it does so at a price. Vertical justification overrides leading, knocking your type off the baseline grid, if you are using one, and potentially making your type color uneven. That said, you do not surrender all control: The Paragraph Spacing Limit setting in

Text Frame Options lets you specify the maximum amount of space permissible between paragraphs. Once the Paragraph Spacing Limit has been reached, you must increase the leading. You can prevent this by specifying a massive amount in the Paragraph Spacing Limit (up to 8,640 points). That way, spacing will be added between paragraphs only (the lesser of the two evils), and the leading is unaffected.

How effective this is depends on how many paragraphs are in the column. If you have subheads and body text, for example, the extra space can usually be added unobtrusively above the subheads. But if the column contains a single paragraph, this approach isn’t going to work. It’s usually preferable to balance rather than vertically align uneven columns. Choose Object > Frame Options (Cmd+B/Ctrl+B), and select Balance Columns.

Figure 7.22 Bottom vertical alignment is useful for picture captions.

Figure 7.23 Vertical justification results in inconsistent leading (right). Balancing columns (left) means that your text columns won’t end on the same baseline as other text columns in the document.